White Sea-Baltic Canal

The White Sea Baltic channel ( Russian Беломорско-Балтийский канал ; transcription: Belomorsko-Baltijskij channel , BBK , Russian Беломорско-Балтийский канал ; to 1961 Stalin White Sea Baltic channel , even briefly Belomorkanal or Stalin channel ) is an 227 km long waterway combined from rivers, lakes and artificial sections , 37 km of which are artificial waterways. It runs from Belomorsk (Soroka) on the White Sea in the north by the lower reaches of WYG , by the addition dammed for sewer purposes Lake Lake Vygozero , via channel sections on Lake Onega and after Povenets . The waterway is part of the White Sea-Baltic Sea Waterway , which connects the Barents Sea with Saint Petersburg .

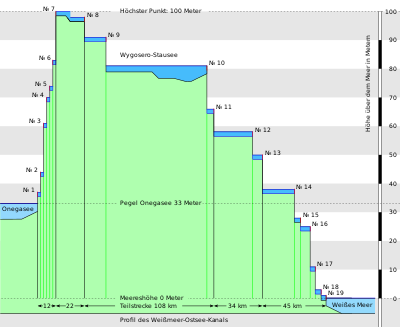

The canal has 19 locks. It was initially navigable for ships up to 3000 t, since modernization work in the 1970s for ships up to 5200 t. The waterway is kept open in winter by icebreakers or it is closed.

It was built from October 16, 1931 to August 30, 1933 on orders from Stalin in connection with the first Soviet five-year plan under the direction of Naftali Frenkel and Genrich Jagoda with the help of tens of thousands of prisoners from the Gulag camp system of the OGPU secret police . In 1983 the canal was awarded the Order of the Red Labor Banner .

The canal is now maintained by the state White Sea Onega Shipping Service, which employs 787 people.

planning

The trade route from the White Sea to Central Russia was already known to merchants in the 16th century. They mainly used the region's lakes and rivers to transport their goods. In the course of the settlement of this northern part of the Russian Empire (the regions of Murmansk , Arkhangelsk etc.), new traffic routes were required on which the goods could be transported to the center of Russia.

Since the construction of a paved land route was postponed again and again due to the high costs, the merchants used the region between the White Sea , Onega and Ladoga Lakes to bring their goods south by water. Since the 19th century there were projects for the construction of a canal, one of which was awarded a gold medal by Vsevolod Timonov at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 . However, the implementation of the project was rejected by the government for reasons of cost. It was only at the beginning of 1917, shortly before the February Revolution , that the Ministry of Transport approved the construction of the canal. This decision became obsolete by the October Revolution and the civil war that followed until 1922.

During the industrialization of the Soviet Union , promoted by Stalin , these plans were considered again. The decision to build the canal was taken on June 3, 1930 by the Labor and Defense Council . The project sketch was approved on July 1, 1931, and project work began a month later on the site of the future construction site. Although the project was not finally accepted until February 1932, the earthworks began on October 16, 1931.

Locks

The 74 kilometers of river and four meters of altitude difference from the mouth of the Neva in the Gulf of Finland to its drainage from Lake Ladoga can be overcome without a lock. There is a connection to Lake Onega via the Swir , one of the main tributaries of Lake Ladoga. In between there are two barrages on hydropower plants (coordinates K01 and K02); their sluices, with lifting heights of around 10 meters each, bring the ships traveling upstream to almost the level of Lake Onega, which is 33 meters in level. The lock structures of the artificially created canal then begin with lock № 1 at the municipality of Powenez (Russian Повене́ц ).

construction

The canal was built largely without the use of steel , concrete or machines . Materials such as wood , stone and earth were almost exclusively moved and used for construction by forced laborers . Their guarding, supply and accommodation was organized by the BelBaltLag (Russian Беломорско-Балтийский ИТЛ, i.e. White Sea-Baltic Corrective Labor Camp), part of the Soviet Gulag system. Most of the so-called canal armists were employed as simple construction workers; Specialists were also arrested for special tasks. After the project was completed in August 1933, 12,484 prisoners were released, and a further 59,516 prisoners were shortened. This resulted in the largest mass layoffs for which the Gulag administration was responsible.

In May 1933 the first ships sailed the White Sea-Baltic Canal, which was finally officially opened on August 30th.

Numerous people died during the construction. Anne Applebaum states that 170,000 prisoners were used in the construction, at least 25,000 were killed, not including those who were withdrawn from the construction site due to occupational accidents or illness and died soon afterwards. According to unconfirmed information from Alexander Solzhenitsyn, however, of the approx. 350,000 construction workers, approx. 250,000 perished during the construction period. The workers received about 1,300 kilocalories of food every day.

According to Solzhenitsyn, the construction projects were poorly carried out because the labor standards were practically impossible for the inmates to meet. At that time, food rations for the prisoners were linked to the fulfillment of the planned target, so that work was recorded that had not actually been performed. "It [the canal] is so shallow that not even the submarines can get through ... Have to be loaded onto barges and pulled".

propaganda

In Soviet propaganda , the building was placed as part of a campaign to “reform” convicts into Soviet citizens who welcomed the social order of the Soviet Union until the mid-1930s. An example of this is the joint publication The Stalin-White Sea-Baltic Canal. The building history ( Russian Беломорско-Балтийский канал имени Сталина. История строительства ), which appeared in 1934 with numerous illustrations, including maps and photos by Alexander Rodchenko , and sent to the participants of the XVII. Party congress was distributed. Under the editorship of Maxim Gorky , Awerbachs and Firins authored writers like Alexei Tolstoy , Boris Pilnyak , Ilf and Petrov , Shklovsky and Soschtschenko a eulogy to the construction of the canal. In 1935 an English-language edition appeared. After most of the NKVD employees who were praised in the volume fell victim to the Great Terror , the book was banned in the Soviet Union in 1937 and withdrawn from circulation. The work contained photos of Stalin and Jagoda, who was arrested and executed as an " enemy of the people " in 1937, side by side at the inauguration of the canal. (→ censorship in the Soviet Union )

Use

The economic as well as military benefits of the canal turned out to be insignificant after completion. The transport volume in 1940 was one million tons, 44% of its capacity. Due to its shallow depth of 3.60 m, it is only navigable to a limited extent. Alexander Solzhenitsyn counted two barges on one day in 1966, each with firewood, Anne Applebaum quotes a lock keeper in August 1999 with a maximum of seven ships a day, often only three or four. Today 10 to 40 ships pass through the canal every day.

Nevertheless, the canal has a certain importance for the industry of the Kola Peninsula and Arkhangelsk Oblast , as it simplifies their exchange of goods with central Russia. It also has a certain strategic use as a link between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea , as it enables parts of the fleet to be relocated .

additional

The cigarette brand БЕЛОМОРКАНАЛ ( Belomorkanal ) of the Papirossa cigarette type is named after the White Sea Canal. The unfiltered cigarettes with a light mouthpiece are considered to be the strongest of their kind in Eastern Europe and because of their low price they became very popular with the inhabitants of the countries of the Soviet bloc. The graphic on the package shows a map with the three artificial waterways marked in red that connect the Black Sea with the Arctic Ocean . Coming from the south, the Kerch Strait leads to the Sea of Azov . From the mouth of the Don , the route continues over the Volga-Don Canal ( ВОЛГО-ДОН ) and the Moskva-Volga Canal ( ИМ. МОСКВЫ ), then up the Volga over the White Lake into Lake Onega and finally into the Belomor Canal ( БЕЛОМОРСКИЙ ).

Narrative literature and essays

In the critical gulag literature, starting with Alexander Solzhenitsyn's The Archipelago Gulag , the construction of canals occupies a large space. Most recently , the Polish writer Marian Sworzeń has written an essay on the responsibility of Soviet writers for Soviet propaganda on the occasion of the opening of the Canal in 1933.

literature

- Cynthia Ann Ruder: Making history for Stalin: the story of the Belomor Canal. University Press of Florida, Gainesville 1998, ISBN 0-8130-1567-7 .

- Anne Applebaum: The Gulag. Translation from English by Frank Wolf. Siedler-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-88680-642-1 . Therein chapter The White Sea Canal , pp. 96-109

- Nick Baron: Soviet Karelia: politics, planning and terror in Stalin's Russia, 1920-1939 . London: Routledge, 2007 ISBN 978-0-415-31216-5

- Ekaterina Makhotina: Proud remembrance and traumatic remembrance: Places of remembrance from the Stalin era on the White Sea Canal . Frankfurt, Main: Lang, 2013 ISBN 978-3-631-60006-1

Web links

- Belomor Canal. International Institute of Social History (English, history of the origins of the White Sea Canal in the Dutch).

- Pictures by the Soviet photographer Alexander Rodschenko (1891–1956) (Russian)

- Website of the "ФБУ Беломорканал" ( federal authority Belomorkanal ) with a photo gallery worth seeing (Russian)

- Günter Kotte : I like to smoke - Belomorkanal: What was left of the Stalin Canal. (pdf, 225 kB) In: SWR2 broadcast “Feature”. February 9, 2020 (also as mp3 audio , 47.8 MB, 53:37 minutes).

Individual evidence

- ↑ The current administration is also located in Medweschjegorsk in the former building of the BelBaltLag management on a street named after Feliks Dzierżyński at number 26.

- ↑ White Sea-Baltic Canal- In: Encyclopedia Britannica , Micropædia, Volume 12, 2002, p 633

- ↑ White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal . In: Meyers enzyklopädisches Lexikon , Volume 25, 1979, pp. 185f.

- ↑ White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal . In: Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, 21st edition , 2005, Volume 29, p. 615

-

↑ Федеральное государственное учреждение "Беломорско-Онежское государственное бассейновое управление водных путей и судоходства" (ФГУ "Беломорканал"): сведения Общие. In: Internet portal of the Republic of Karelia . Archived from the original on April 23, 2017 ; accessed on February 7, 2020 (Russian). Konstantin Wassilewitsch Gnetnew (Константин Васильевич Гнетнев): Беломорский Канал. In: petrozavodsk-mo.ru. Retrieved February 7, 2020 (Russian).

- ^ Karl Schlögel: The Soviet Century . Archeology of a Lost World. CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-71511-2 .

- ^ Anne Applebaum: The Gulag . Translated from the English by Frank Wolf. Siedler, Munich 2003, p. 102 and p. 104, ISBN 3-88680-642-1 .

- ↑ Timothy Snyder : Bloodlands . 2nd edition 2014, p. 49.

- ↑ In: The Gulag Archipelago .

- ↑ Maxim Gorki, Leopold Awerbach, Semjon Firin (ed.): The White Sea-Baltic Canal . Moskva, Intourist, around 1934, DNB 57828944X

- ↑ Gorky, Maxim; Leopold Averbakh; Semen Georgievich Firin; tr. Amabel Williams-Ellis (1935). The White Sea canal: being an account of the construction of the new canal between the White Sea and the Baltic Sea. London: John Lane

- ↑ Nina Frieß: "To what extent is that interesting today?" - Memories of the Stalinist Gulag in the 21st century. Frank & Timme, Berlin 2017, p. 46.

- ↑ Bastiaan Kwast: The White Sea Canal: A Hymn of Praise for Forced Labor , 2003.

- ↑ Mikhail Morukov: The White Sea – Baltic Canal (PDF; 67 kB) ; in: Paul R. Gregory, Valery Lazarev (Eds.): The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag , 2003

- ^ Anne Applebaum, Der Gulag , 2003, p. 109