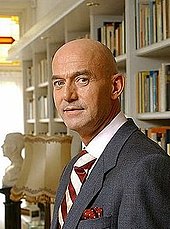

Pim Fortuyn

Pim Fortuyn (born February 19, 1948 as Wilhelmus Simon Petrus Fortuijn in Driehuis in the municipality of Velsen ; † May 6, 2002 in Hilversum ) was a Dutch politician of the right-wing populist LPF , publicist and sociologist .

He represented controversial positions: he declared the multicultural society to have failed, he was a declared opponent of the monarchy and the influential position of the churches; he spoke out against a political Islam and in favor of an open society , also with reference to his own homosexuality . His defensive stance on animal welfare issues with statements such as "Choose me, then you can wear fur coats" led to controversy. Shortly before the parliamentary elections in 2002, he was shot dead in an attack in Hilversum.

Life

Fortuyn came from a Catholic- Conservative family, the father was a sales representative. After graduating from school in 1967, he studied sociology , history , law and economics, first at the University of Amsterdam and later at the Free University of Amsterdam . In 1971 he graduated in sociology and received his doctorate in 1980 at the University of Groningen in the field of sociology, where he lectured from 1972 to 1988, first in Marxist sociology and later in economic and social policy.

During his time in Groningen, he was interested in Marxist-Leninist theories and sympathized with the CPN , a communist party in the Netherlands. He later became an active member of the social democratic PvdA . In 1986 Fortuyn received a position in the Socio-Economic Council (SER) (advisory body for employers and workers' associations and government representatives) and in 1989 he became director of OV-Studentenkaart BV , the central office for organizing student cards for public transport.

In 1988 Pim Fortuyn moved to Rotterdam , where he was Associate Professor at the Erasmus University from 1990 to 1995 . He published his positions in books and columns. He wrote for eight years for the liberal-conservative weekly Elsevier . In his columns he appeared as a critic of the social liberal cabinet (popularly known as the “violet cabinet”). In 1992 he wrote To the People of the Netherlands , in which he described himself as the successor to the patriotic politician Joan Derk van der Capellen who protested against the political establishment in the 18th century in a pamphlet of the same name. In 1995 De verweesde samenleving (“society without a man ”) appeared, and in 1997 Tegen de islamisering van onze cultuur (“Against the Islamization of our culture”).

On August 20, 2001, he announced that he wanted to go into politics. How this decision came about is described by the German-Syrian political scientist and publicist Bassam Tibi in the time (23/2002) as follows:

“In May 2000 I took part in an event organized by the 'European Capital of Culture' in Rotterdam. It was at this point in time that violent attacks by the Imam of Rotterdam against homosexuals aroused people's hearts. The imam - who, by the way, expressly does not see himself as a European citizen, but as a Moroccan Muslim - stated among other things: 'The gays must be fought; they are a danger to peace. ' Alarmed by such statements, the sociology professor Pim Fortuyn wrote a book entitled 'Against the Islamization of Our Culture'. Fortuyn, an avowed homosexual, went into politics. "

On November 26th of the same year he was the top candidate of the party Leefbaar Nederland (LN, German Livable Netherlands ), a right-wing civil party, on January 20, 2002 also by Leefbaar Rotterdam . About Islam, he said, “I don't hate Islam,” but “I think it's a backward culture ... Wherever Islam is in charge, it's just terrible. All the ambiguities. It is almost a little like the Reformed. Reformed people lie all the time ”(with which he referred in particular to the Gereformeerde Kerk , one of the many evangelical denominations in the Netherlands). Fortuyn said that as an avowed homosexual, he felt personally threatened after a prominent imam told him that gays were worth less than pigs. In the interview, Fortuyn admitted that his statements about Islam would likely cause him problems with Leefbaar Nederland . In fact, these statements led to the break. A few days later Fortuyn founded his own right-wing populist party Lijst Pim Fortuyn . In April 2002 he published his eleventh book: De puinhopen van eight jaar paars kabinet (“The shambles from eight years of the violet cabinet”), which was also used as an election platform . At the book presentation, a 27-year-old German student threw a cake in his face in protest.

Views

In August 2001, the Rotterdam Dagblad quoted him : “I am also for a cold war with Islam. I see Islam as an extraordinary threat, as a hostile society. ”Various organizations reported him because of this statement with reference to the Dutch anti-discrimination law. However, the ads were unsuccessful because Fortuyn's statements were covered by the fundamental right to freedom of expression . On February 9, 2002, he said in an interview with the left-liberal daily De Volkskrant that the Netherlands, with 16 million inhabitants, was no longer receptive and that forty thousand asylum seekers per year were unacceptable. He also said that it would be better to delete the first article of the Dutch Basic Law (“Nobody should be discriminated against”) than to restrict freedom of expression.

Fortuyn was a declared republican and a member of the republicein Genootschap , an association for the abolition of the monarchy . However, more than 80% of the population support the monarchy. When asked about this, he declared that he would respect the constitutional conditions in the Netherlands and the Dutch Basic Law, but would rather have an elected president today than tomorrow rather than a queen determined by inheritance law. Fortuyn was also a proponent of the US two-party system .

influence

“Even if Fortuyn never governed, he made lasting changes,” writes historian and Netherlands expert Christoph Driessen . “His own list Pim Fortuyn soon disappeared from the scene, but right-wing populism established itself as an integral part of politics. Its potential includes around 20 percent of the electorate. Fortuyn's heir was the bizarre Geert Wilders . "

rating

Fortuyn "simply contradicted everything that had been associated with the Netherlands up until then," comments Christoph Driessen . In a country known for its stability, he upset the entire party landscape. The political culture was characterized by objectivity and willingness to compromise, but Fortuyn “was a polemicist who called for conflict instead of consensus. He was a good speaker, didn't use technical jargon and knew no taboos. Many Dutch people found this beneficial. In retrospect, his appearance seems all the more unreal because it was limited to a few months, from the end of 2001 to May 2002. ”This has reinforced his“ redeeming aura ”. Driessen sums up: “Fortuyn was not a racist rambling about the people and fatherland, but he was a demagogue and populist. He picked up moods from the population, simplified, defamed, but offered no solutions. (...) Fortuyn had no real program, not even a vision, just a nostalgic longing for a country that had never existed: a Holland without foreigners and criminality, but at the same time liberal and modern. "

Political career

- Active member of the PvdA until 1989, then VVD member

- Top candidate for Leefbaar Nederland (elected on November 26, 2001 for the parliamentary elections of May 15, 2002)

- Lead candidate for Leefbaar Rotterdam for the municipal council elections in March 2002 (the party won around 30% of the seats)

- Top candidate for Lijst Pim Fortuyn from February 11, 2002

attack

On May 6, 2002, shortly before the general election, Fortuyn was gunned down by a man on the way to his car. Fortuyn died shortly after the attack. After the attack became known, some of his supporters rioted through the city center of The Hague and fought violent street battles with the police the following night. In order to prevent riots against foreigners, a spokesman for the Dutch Ministry of the Interior repeatedly pointed out that the attacker was not a foreigner, but a "white Dutchman". The assassin Volkert van der Graaf was an activist of various environmental protection organizations .

funeral

Fortuyn was buried on May 10, 2002 in the Westerveld cemetery in Driehuisin in the province of Noord-Holland according to the Roman Catholic rite. The funeral in the Netherlands grew partly into a political demonstration. Flowers were thrown onto the hearse to applause. Many political observers viewed this as a breach of tradition.

According to his will, his body was transferred on July 20, 2002 to Provesano in the municipality of San Giorgio della Richinvelda in the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia . He is buried in the Provesano cemetery. Fortuyn also had a house in Provesano. His tomb , five meters wide and three meters high , was carved from 320 tons of Carrara marble and topped with a large cross. At the foot is the coat of arms of the Fortuyn family and an epitaph with the following inscription in Latin : "Loquendi libertatem custodiamus" ("Let's defend freedom of expression!"). The stonemason Bruno Ambrosios, who was friends with Fortuyn for years, declares that Provesano “loved and respected” his friend Ambrosios together with Fortuyn's former colleague Jean Hooft, who gave the funeral oration in Italian and Dutch . At Fortuyn's request, the Ave Maria was played by Franz Schubert . Only one memorial stone remained in the Westerveld cemetery.

The consequences

Numerous conspiracy theories emerged that had a lasting impact on Dutch politics. The then head of the Social Democratic Labor Party, Ad Melkert , said: “The Netherlands has lost its innocence.” Many foreign media were also interested in the attack. On the day after the attack, the Kok II cabinet decided , after prior consultation with representatives of the LPF, that the parliamentary elections on May 15 should take place as planned. The election campaigns were suspended for a week. The phrase "Pim had het zo gewild" ("Pim would have wanted it that way") is still used by Fortuyn supporters and cartoonists .

A discussion ensued as to whether left-wing critics of Fortuyn had some sort of indirect complicity in the attack.

The press spokesman for the LPF, Mat Herben , announced that Pim Fortuyn would remain the posthumous top candidate until after the elections. Herben was only supposed to replace him as group leader after the elections. The LPF was accepted into the government by the new Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende after successful elections , but the inexperience and disagreement among most LPF parliamentarians led to the overthrow of the cabinet after only 87 days. In the new election in 2003, voters' approval collapsed, the LPF disappeared completely from parliament in the parliamentary elections of 2006 and finally dissolved on January 1, 2008. In the course of its decline, several successor parties emerged, of which only the Partij voor de Vrijheid by Geert Wilders is represented in parliament today. Ahmed Aboutaleb , Social Democratic Mayor of Rotterdam, said in 2009 that Fortuyn was "a follower of democratic principles" who defended freedom of expression "with fire and sword".

The assassin

Volkert van der Graaf (born July 9, 1969 in Middelburg ), who shot Fortuyn in the parking lot of the state radio in Hilversum , worked as a militant animal rights activist for various radical animal rights and environmental organizations. He studied at the Agricultural University of Wageningen and was a founding member of the Vereniging Milieu-Offensief and the Animal Liberation Front in the Dutch province of Zeeland . Between 1992 and the attack on Fortuyn, the Vereniging Milieu-Offensief 2220 initiated environmental proceedings against factory farmers and smaller livestock farms. Van der Graaf was allegedly under surveillance by Dutch state organs before the act.

Van der Graaf initially refused to give a statement about his motives and later stated in the 2003 trial that he wanted to “ protect Muslims ”. Fortuyn used them as “scapegoats” and made a name for himself politically at the expense of the “weakest sections of society”. In addition, Fortuyn was a "danger to society". In interrogations, van der Graaf said that he had been thinking for six months how to stop Fortuyn's activities and silence him, and later it was difficult for him to distance himself from the attack. Fortuyn's family members wore fur clothing during the trial to show their presence and revulsion towards the animal rights activist.

On April 15, 2003, the Amsterdam court sentenced the perpetrator to 18 years' imprisonment. An expert opinion confirmed that he had an obsessive-compulsive personality disorder , but left no doubts about his culpability at the time of the crime. An Asperger's syndrome was excluded as debt reduction. Under Dutch law, the earliest possible release is two-thirds of the sentence, and accordingly van der Graaf was released from prison after twelve years on May 2, 2014, subject to conditions including wearing an electronic ankle bracelet .

literature

- Christoph Driessen : Earthquake. Der Pim-Fortuyn-Schock, in: ders .: History of the Netherlands, From the sea power to the trendland, Regensburg 2016, pp. 262–273

- Frank Eckardt : Pim Fortuyn and the Netherlands. Populism as a reaction to globalization. Tectum, Marburg 2003, ISBN 3-8288-8494-6 .

- Clemens van Herwaarden: Fortuyn, Chaos en Charisma. Bert Bakker 2005. ISBN 90-351-2819-2 (Dutch)

- Tomas Ross: The candidate's death. dtv, Munich 2009. ISBN 978-3-423-21127-7 (detective novel, which fictionally processes Pim Fortuyn's murder; awarded the Gouden Strop as best Dutch suspense novel in 2003; filmed by Theo van Gogh as The Sixth May ).

- Friso Wielenga , Florian Hartleb (Ed.): Populism in modern democracy: The Netherlands and Germany in comparison. Waxmann, Münster / New York, NY / Munich / Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-8309-2444-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Pim Fortuyn in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bassam Tibi : "Blessed are those who are lied to" In: Die Zeit , edition 23/2002 via Evangelisch-Free Church Community Berlin .

- ↑ Christoph Driessen : History of the Netherlands. From sea power to trend land . Regensburg 2016, p. 272.

- ↑ Christoph Driessen : History of the Netherlands. From sea power to trend land . Regensburg 2016, p. 268.

- ↑ a b Pim Fortuyn buried in Italy , July 20, 2002 on derstandard.at online

- ^ A b Joan Clements and Bruce Johnston: Fortuyn exhumed on TV for Italian reburial on telegraph, July 20, 2002 online

- ^ Jelle van Buuren: Holland's Own Kennedy Affair. Conspiracy Theories on the Murder of Pim Fortuyn ( Historical Social Research 38, 2013), pp. 257-285.

- ↑ a b Who sows hatred reaps hatred. on Europe Online Magazine , May 4, 2012.

- ↑ Fortuyn - with "fire and sword" for freedom: 10th anniversary of death - WORLD. Retrieved February 11, 2017 .

-

↑ Janet Louise Parker: Jihad Vegan. ( Memento of July 14, 2011 on the Internet Archive ) at: newcriminologist.com , June 20, 2005. New Criminologist

- The recent brutal murders of a prominent Dutch politician who was destined to be Prime Minister (Pim Fortuyn) and a controversial film director (Van Gogh), have led the Dutch Intelligence Service to consider the tortuous connections between the Radical Animal Rights Movement, Radical Islamic Terrorists and Organized Crime.

- ^ Culture Shock , James Graaf / Rotterdam, Time Magazine , May 13, 2002.

-

↑ Fortuyn killed 'to protect Muslims' , The Daily Telegraph , March 28, 2003:

- [van der Graaf] said his goal was to stop Mr Fortuyn exploiting Muslims as "scapegoats" and targeting "the weak parts of society to score points" to try to gain political power.

- Van der Graaf, 33, said during his first court appearance in Amsterdam on Thursday that Fortuyn was using "the weakest parts of society to score points" and gain political power.

- ↑ 18 years imprisonment for Fortuyn assassins. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , April 15, 2003.

- ↑ Welt Online: Pim Fortuyn's killer is released from prison , May 2, 2014

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Fortuyn, Pim |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fortuijn, Wilhelmus Simon Petrus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dutch sociologist, politician (LPF) and publicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 19, 1948 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Velsen ( North Holland ), Netherlands |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 6, 2002 |

| Place of death | Hilversum |