Italian language

| Italian (Italiano) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

See under “Official Status”, furthermore in numerous countries with immigrants of Italian origin | |

| speaker | 85 million including 65 million native speakers (estimated) | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Recognized minority / regional language in |

Koper , Izola and Piran ( Slovenia ) Istria County ( Croatia ) |

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

it |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

ita |

|

| ISO 639-3 | ||

Italian (Italian lingua italiana , italiano [ itaˈli̯aːno ]) is a language from the Romance branch of the Indo-European languages . Within this branch of language, Italian belongs to the group of Italian-Romance languages .

distribution

Italian is spoken as a mother tongue by around 65 million people worldwide . In addition to Italy , the Italian-speaking area in Europe also includes areas of neighboring Switzerland. As an official language, Italian is also widely used as a second and learned foreign language among the numerous ethnic groups and linguistic minorities in Italy: the Germans and Ladins in South Tyrol , the Slovenes in Friuli-Venezia Giulia , the Franco-Provencal regions in Aosta Valley and the Occitans in Piedmont , the Friulians , the Sardinians , the Albanian and Greek- speaking minorities of southern Italy , the Molises Slavs .

Italian is the official language in the following countries:

| States with Italian as the official language | |

|---|---|

|

|

around 56 million native speakers |

|

|

about 525,000 native speakers, mainly in the Italian part of Switzerland , plus the 300,000 Italo Swiss in the rest of the country |

|

|

about 30,000 |

|

|

about 1,000 |

Italian is also the official language of the Order of Malta .

Italian enjoys the status of a regional official language in Slovenia and Croatia , in the areas of the historical region of Venezia Giulia . The Slovenian municipalities of Capodistria / Koper , Isola d'Istria / Izola and Pirano / Piran as well as the Croatian County of Istria are officially bilingual.

In the former Italian colonies in Africa , Libya , Somalia and Eritrea , Italian was used as a commercial language alongside English , but has lost much of its importance since decolonization: It is mainly spoken or at least understood by the elderly. In Somalia, the 2004 transitional constitution stipulates that Italian should be a secondary language alongside English .

Many emigrants of Italian origin around the world still speak Italian. In Buenos Aires, Cocoliche , a mixed language with Spanish, developed strongly at times .

Italian words have been incorporated into various terminologies , e.g. B. in music , design , technology , kitchen or banking .

|

|

The Italian-speaking world Blue: official language |

history

Like all Romance languages, Italian is derived from Latin . At the beginning of the Middle Ages after the collapse of the Roman Empire , Latin remained in Europe as an official and sacred language . Latin also asserted itself as a written language . However - even when the Roman Empire still existed - people spoke a form of language that deviated from the written standard and is also known as vulgar Latin or spoken Latin . From this the pro-Romanic vernacular and finally the Romance individual languages developed. New languages emerged in Italy and its neighboring countries, e. B. the Oïl languages in northern France , the Oc languages in southern France and the Sì languages in Italy, named by Dante Alighieri after the respective designation for "yes".

The stages of the Italian language can be summarized briefly in the following epochs:

- Old Italian-Romansch (9th – 10th centuries): Italo-Romanic texts from various regions

- Old Italian (1275–1375): Increase in old Tuscan documentation and the creation of important literary works (until Boccaccio's death).

- Old Italian / New Italian (1375–1525): Adoption of diatopic and diastatic innovations into Florentine.

- New Italian (1525–1840): From the codification of Trecento-Florentine to Manzoni's revision of his Promessi sposi on a New -Florentine basis.

- Italiano del Duemila: present and recent past.

The first written evidence of the volgare (from Latin vulgaris , “belonging to the people, common”), i.e. the Italian vernacular as the origin of today's Italian, date from the late 8th or early 9th century. The first is a riddle found in the Biblioteca Capitolare di Verona , called the Indovinello veronese ( Veronese riddle ):

- "Se pareba boves, alba pratalia araba, albo versorio teneba et negro semen seminaba."

- [She] pushed cattle, tilled white fields, held a white plow, and sowed black seeds.

- [Meant is the hand]: cattle = (deep) thoughts, white fields = pages, white plow = feather, black seeds = ink

The spread of the volgare was encouraged by practical necessities. Documents concerning legal matters between persons who did not speak Latin had to be drafted in an understandable manner. One of the oldest language documents of Italian is the Placito Cassinese from the 10th century: "Sao ko kelle terre, per kelle fini que ki contene, trenta anni le possette parte Sancti Benedicti." (Capua, March 960). The Council of Tours recommended in 813 that the vernacular should be used instead of Latin in preaching. Another factor was the emergence of cities around the turn of the millennium, because city administrations had to make their decisions in a form that was understandable for all citizens.

For centuries, both the vernacular Italian and Latin, which was still used by the educated, coexisted. It was not until the 13th century that an independent Italian literature began, initially in Sicily at the court of Frederick II ( Scuola siciliana ). Writers had a decisive influence on the further development of Italian, as they first created a supra-regional standard in order to overcome the language differences between the numerous dialects. Dante Alighieri , who used a slightly modified form of the Florentine dialect in his works, was particularly influential here. Francesco Petrarca and Giovanni Boccaccio , who, together with Dante, are known as the tre corone ("three crowns") of Italian literature , also had a great influence on the Italian language in the 14th century .

In the 16th century, the form and status of the Italian language was discussed in the Questione della lingua , with Niccolò Machiavelli , Baldassare Castiglione and Pietro Bembo having a decisive influence . A historicizing form of the language that was based on the Tuscan of the 13th / 14th centuries prevailed. Century.

However, the real standardization, especially of the spoken language, only took place as a result of national unification . In the 19th century, the “Florentine” dialect became the standard Italian language in the united Italy. This is thanks, among other things, to the second version of the novel I Promessi Sposi by Alessandro Manzoni .

Language variants

A diglossia is typical for the entire Italian- speaking area : this means that standard Italian is only used in writing and in formal situations, but the respective dialect (dialetto) for informal oral communication . Its spread has only recently declined somewhat, favored by increased mobility and consumption of mass media. Regionally colored varieties of Italian are being used as an intermediate form.

The individual dialects of Italian are sometimes very different from one another; some language varieties are classified as independent languages. All Italian dialects and Romance languages spoken in Italy can be traced back directly to (vulgar) Latin . In this respect, one could - exaggerated - also describe all the Romance idioms of Italy as "Latin dialects".

A distinction is made between northern, central and southern Italian languages and dialects. The northern Italian share in galloitalische and venezische dialects. The dialect borders lie along a line between the coastal cities of La Spezia and Rimini or Rome and Ancona . The northern Italian languages are historically more closely related to the Rhaeto-Romanic and Gallo-Roman languages (i.e. French , Occitan and Franco-Provencal ) than to central and southern Italian.

The Tuscan dialect, in particular the dialect of Florence , in which Dante Alighieri , Francesco Petrarca and Giovanni Boccaccio wrote and from which the high-level Italian language developed, was historically regarded as a prestigious variety . To this day, the term "Tuscan" is sometimes used when referring to standard Italian (as opposed to other Italian dialects).

Some Italian regional languages such as Sicilian or Venetian can also have their own literary tradition (the so-called Scuola siciliana in the time of Frederick II ), which is why these (and other dialects) are also classified as an independent language . Sicilian also has so many peculiarities in terms of sound formation and vocabulary that it is more of a language closely related to Italian (and not a dialect).

From a linguistic perspective, Corsican is also a dialect of Italian, even one that is relatively closely related to Tuscan and thus to today's standard Italian. As a result of the political annexation of Corsica to France in 1768 , however, the linguistic " roofing " by Italian ceased to exist and it is now often treated as an independent language.

The classification of Sardinian , Ladin and Friulian as individual languages (or in the case of the latter two as variants of Rhaeto-Romanic, but not Italian) is now recognized in linguistics.

Phonetics and Phonology

Vowels

Main tone vowels

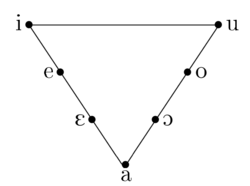

Italian has 7 main tone vowels.

- [i]: The front tongue lies on the anterior hard palate and the tip of the tongue on the alveoli of the lower incisors. The lips are spread apart. Example: i sola - [ˈiːzola].

- [e]: The tongue is not quite as high as in the [i] and the tip of the tongue touches the lower teeth. The lips are less spread and the mouth is more open than in the [i]. Example: m e la - [ˈmeːla].

- [ɛ]: The tongue is moderately raised and slightly arched forward. The tip of the tongue touches the lower incisors. The lips are less spread than in the [e] and the mouth is slightly open. Example: b e lla - [ˈbɛlːa].

- [a]: The Italian [a] lies between [a] ("light" a ) and [ɑ] ("dark" a ). The tongue is at rest, the lips and mouth are open. Example: p a ne - [ˈpaːne].

- [ɔ]: The Italian [ɔ] is spoken quite openly. It's a back tongue sound . The tongue is withdrawn and arched against the soft palate (velum). The tip points downwards. The lips are in the shape of a vertical ellipse. Example: r o sa - [ˈrɔːza].

- [o]: The Italian [o] is roughly in the middle between [ɔ] and [o]. So it is implemented relatively openly. The tongue is slightly withdrawn and lowered. The lips are turned forward and rounded. Example: s o tto - [ˈsotːo].

- [u]: The Italian [u] is a back tongue vowel. The back of the tongue is arched towards the soft palate. The lips are rounded and strongly everted. Example: f u ga - [ˈfuːɡa].

Secondary tone vowels

Italian has 5 secondary tone vowels. The open vowels [ɛ] and [ɔ] are omitted for the unstressed vowels. In comparison to the main tone vowelism (7 vowels), this creates a system with 5 vowels that is reduced in the secondary tone.

Consonants

- consonant

A consonant is a speech sound that interrupts or restricts the flow of air when it is formed. Italian has 43 consonants that can be classified by the following articulatory parameters:

The following modes of articulation are important for Italian: plosive , nasal , fricative , approximant and lateral .

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

alveolar |

post- alveolar |

palatal | velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p b | t d | k ɡ | |||

| Nasals | m | ɱ | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Vibrants | r | |||||

| Fricatives | f v | s z | ʃ | |||

| Approximants | w | j | ||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||

| Affricates | ts dz | tʃ dʒ |

Source: SAMPA for Italian

Plosives

[b, d, g] are pronounced voiced and [p, t, k] are not spoken aspirated.

- [p, b] bilabial plosive sound (between upper and lower lip): p asta, b asta

- [t, d] alveolar-coronal closure sound (with the tip of the tongue on the posterior surfaces of the tooth / tooth sheath): t assa , nu d o

- [k, g] palatal / velardorsal closure sound (with hard / soft palate and the back of the tongue): c ampo , g amba

Nasals

With nasals, a seal is formed in the oral cavity so that the airflow escapes through the nose.

- [m] bilabial: m a mm a

- [n] adental-coronal or alveolar-coronal also dental coronal in certain cases: n o nn o

- [ɱ] labiodental; before [f, v]: i nf erno, i nv erno

- [ŋ] velar-dorsal; before [k, g]: an che, d un que

- [ɲ] palatal: vi gn a, campa gn a

Vibrants

Vibrants are sounds that are formed by flapping the tip of the tongue three to five times on the upper tooth dam (" rolled R ").

- [r]: t r eno, r e

Fricatives

With fricatives, the airflow is narrowed with the help of the articulation organ. There is a rubbing noise.

- [ʒ] occurs in the Italian language only in foreign words or in the affricata [dʒ].

- [f, v] labiodentaler Engelaut (between lower lip and upper incisors): f ino, v ino

- [ʃ] post-alveolar angelaut: sci are, sci opero

- [s, z] dental-alveolar Engelaut: ba ss e, ba s e (The voiced pronunciation [z] can only occur between vowels, but does not appear consistently there either.)

- [j] palatal-dorsal: naz i one, diz i onario

Lateral

Laterals are sounds that are delimited by the edges of the tongue and the molars.

- [l] denti-coronal: l usso, ve l o

- [ʎ] apico -alveolar or apico-dental: gli , fi gli o

Affricates

An affrikata is an oral closure sound in which the closure is loosened so far in the second phase that a fricative is created. They are scored either monophonematic (i.e. as one phoneme) or biphonematic (two consecutive phonemes). In addition, a distinction is made between homorganen (formation of the lock and friction with the same organ of articulation) and heterorganen (formation with different organs of articulation) affricates. Affricates in Italian include the sounds [dz], [ts] (homorgan) and [dʒ] and [tʃ] (heterorgan).

- [dz, ts] z ero, can z one (There is no clear rule whether the z is spoken voiced [dz] or unvoiced [ts].)

- [dʒ] [tʃ] gi apponese, c inese

Geminates

Italian distinguishes between short and long consonants. Geminates (from Latin geminare = to double) are usually written as double consonants and pronounced elongated. The difference between single and long consonants is significant in Italian. Example:

- fa t o - ['faːto] "Fatum, Destiny"

- fa tt o - ['fatːo] "made, created"

The preceding vowel is shortened.

Certain phonemes such as [ʎː], [ɲː], [ʃː], [ts] and [dz] always appear as geminates intervowels, even if they only occur simply in the script. Example:

- fi gli o - ['fiʎːo]

- ra gn o - ['raɲːo]

- la sci are - [laʃ'ʃa: re]

- a z ione - [at'tsjo: ne]

- ma z urca - [mad'dzurka]

Relationship between sound and letter

The Italian spelling reflects the phonetic level fairly accurately, similar to the Spanish or Romanian . Today's Italian uses the Italian alphabet , which is made up of 21 letters of the Latin alphabet . The letters k , j , w , x , y only appear in Latinisms , Graecisms or foreign words. The j is sometimes found in historical texts for a double i (which is no longer written today) . In contrast to Spanish, Italian has no continuous marking of the word accent . A grave accent (`) is only used for end-stressed words (example: martedì , città , ciò , più ) - for e , an acute accent (´) or grave accent (`): piè [pjɛː], perché [perˈkeː], depending on the pronunciation . In very rare cases, acute is also used for o . The circumflex is sometimes found in texts to indicate the merging of two i's , for example i principi ("the princes", from principe) as opposed to i principî ("the principles", from principii , from principio) . Other examples are gli esercizî and i varî . For the sake of clarity, the accent is occasionally used to differentiate meanings ( e - "and", è "he is"), sometimes also in dictionaries or on maps.

The letters g, c and letter combinations with sc

The following combinations of letters in Italian spelling are particularly important:

- Following the letter g a e or i , this is g as dsh ( IPA : [ ʤ ] ) pronounced.

- Followed by the letter c a e or i , then this is c like ch (IPA: [ ʧ ] ) pronounced.

- If an unstressed i is immediately followed by another vowel , it remains mute - it leads to the change in g or c described above , but is not spoken itself, e.g. B. in Giove [ ʤɔ.ve ] and Ciabatta [ tʃaˈbatːa ].

- The h is always mute. B. the described effect of e or i can be canceled: d. H. Spaghetti is pronounced [ spaˈ ɡ ɛtːi ]; Spagetti (without an h ) would be pronounced like [ spaˈ ʤ ɛtːi ].

- g and c in front of a , o or u are as [ ɡ ] or [ k ] pronounced.

- The above rules also apply to the double consonants (see there) gg and cc : bocca [ 'bokːa ], baccello [ baˈʧːɛlːo ], bacchetta [ baˈkːetːa ], leggo [ ' lɛgːo ], maggio [ 'madʤo ].

- The situation is similar with the letter combination sc (h) : scambio [ 'skambjo ], scopa [ ˈskoːpa ], scuola [ ˈskwɔla ], schema [ ˈskɛma ], schivo [ ˈskiːvo ], but: scienza [ ˈʃɛnʦa ], sciagura [ ʃaˈguːra ]. [ ʃ ] corresponds to the German letter combination sch .

| Pronunciation of c | Spelling when followed by a light vowel |

Spelling when followed by a dark vowel |

|---|---|---|

| soft [ ʧ ] | c or cc | ci or cci ¹ |

| hard [ k ] | ch or cch | c or cc |

| Pronunciation of g | ||

| soft [ ʤ ] | g or gg | gi or ggi ¹ |

| hard [ ɡ ] | gh or ggh | g or gg |

| Pronunciation of sc | ||

| soft [ ʃ ] | sc | sci ¹ |

| hard [ ˈsk ] | sch | sc |

¹ In these cases there are exceptions where the i is not mute, e.g. B. farmacia [ farmaˈtʃi.a ], magia [ ma'ʤia ], leggio [ le'ʤːio ] or sciare [ 'ʃiare ].

In some words, the character sequence sc is pronounced after a vowel ([s: k] before a , h , o and u ; or [ʃ:] before e and i ).

Letter combinations with gl and gn

- The letters gl corresponds to a palatalized "l" (corresponding to "ll" Spanish), a close fusion of the sounds [ l ] and [ j ] (IPA: [ ʎ ] ), like in "bri ll ant", "Fo li e".

- The letter sequence gn corresponds to a mouillated “n” (“ñ” in Spanish (señora), “нь / њ” in Cyrillic script , “ń” in Polish , “ň” in Czech (daň), same as “gn” in French) (AA) or in Hungarian "ny", a close fusion of the sounds [ n ] and [ j ] (IPA: [ ɲ ] ), as in "Ko gn ak" , Champa gn e).

Phoneme inventory

Half vowels and half consonants as phonemes

With regard to the semi-vowels [i̯] and [u̯] or semi-consonants [j] and [w] that exist in Italian, the question arises to what extent these can be regarded as independent phonemes. Researchers like Castellani and Fiorelli believe that this is definitely the case. The comparison of word pairs in which the vowel and the semi-vowel / semi-consonant appear in the same place is the only way to clarify this question. So serve as examples:

- piano - [pi'a: no] (from Pio ) and piano - ['pjaːno]

- spianti - [spi'anti] ( verb spiare ) and spianti - ['spjanti] (verb spiantare )

- lacuale - [laku'a: le] and la quale - [la 'kwaːle]

- arcuata - [arku'a: ta] and Arquata - [ar'kwaːta].

rating

The opposition between the vowel and the semi-vowel / semi-consonant found in these word pairs is offset by the problem of individual language realization. In order to be able to start from the semi-vowels / -consonants as independent phonemes, these word pairs must always be pronounced differently and thus can be understood in their special meaning regardless of the context. However, this cannot be assumed, since the language realization depends on factors such as “speaking speed, individual characteristics or the sound environment in the neighboring word” . In poetry, for example, pronunciation can vary for rhythmic reasons. Based on these findings, researchers like Lichem and Bonfante come to the conclusion that the respective half-vowels and half-consonants in Italian "are in a positional alternation with one another" and "that the Italian half-vowels are combinatorial variants of the corresponding vowel phonemes, i.e. not their own phonemes" .

grammar

Language example

Universal Declaration of Human Rights , Article 1:

- Tutti gli esseri umani nascono liberi ed eguali in dignità e diritti. Essi sono dotati di ragione e di coscienza e devono agire gli uni verso gli altri in spirito di fratellanza.

- All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Language traps: "Falsi amici"

The following articles deal with the typical mistakes that can occur when learning and translating the Italian language:

See also

literature

- Eduardo Blasco Ferrer: Handbook of Italian Linguistics. Schmidt, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-503-03054-9 ( Basics of Romance Studies. 16).

- Patricia Bourcillier, Bernd Sebastian Kamps : Italian between the hills of Venus and the loins of Adonis'. Foreign language in tender and voluptuous shades. Steinhäuser, Wuppertal 2006, ISBN 3-924774-11-0 ( online ).

- Amerindo Camilli: Pronuncia e grafia dell'italiano Firenze, 1965 (3rd edition).

- Otto Dorrer: Pocket dictionary of the German and Italian language for the chemical industry - Dizionario Tascabile delle lingue tedesca e italiana per l'industria chimica , Verlag Chemie GmbH, Berlin W 35 1943, DNB 572904312 .

- Günter Holtus , Michael Metzeltin , Christian Schmitt (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Romance Linguistics . 12 volumes. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1988-2005; Volume IV: Italian, Corsican, Sardinian. 1988.

- Dieter Kattenbusch : Basics of Italian Linguistics. Haus des Buches, Regensburg 1999, ISBN 3-933516-00-5 ( Basic knowledge of linguistics. 1).

- Klaus Lichem: Phonetics and Phonology of Modern Italian. Academy, Berlin 1970.

- Max Pfister : Lessico Etimologico Italiano . Reichert, Wiesbaden 1979 ff., ISBN 3-88226-179-X .

- Ursula Reutner , Sabine Schwarze: History of the Italian language. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2011.

Web links

- DOP . RAI ( Dizionario d'ortografia e di pronunzia , dictionary of Italian spelling and pronunciation; Italian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Introduction to Old Italian. University of Cologne, October 11, 2010, p. 27 , archived from the original on October 11, 2010 ; Retrieved on September 6, 2016 (Old Italian (1275–1375): Increase in old Tuscan documentation and the emergence of important literary works (up to Boccaccio's death).).

- ^ Georg Bossong : The Romance Languages. A comparative introduction. Buske, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-87548-518-9 , p. 197.

- ^ A b Bossong: The Romance Languages. 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Bossong: The Romance Languages. 2008, p. 173 ff.

- ↑ Italian ( English ) SAMPA. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ A b c Klaus Lichem: Phonetics and Phonology of today's Italian. Academy, Berlin 1970, § 25.