Arbëresh

The Arbëresh ( IPA : ar'bəreʃ ) are a long-established Albanian ethnic minority in central and southern Italy and on the island of Sicily , who are protected in Italy by Law No. 482 “For the Protection of Historical Language Minorities” of December 15, 1999. Their scattered settlement area is called in Italian " Arbëria " (also: Arberia).

The term Arbëresh means "Albanian" and has its origins in the word Arber / Arbëri , which was used to name the region of today's Albania in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Arbëresh came sporadically in several smaller and larger waves of migration to what is now Italy. While in the beginning there were mercenaries ( stratiotes ) who were in the service of the local feudal lords and the kings of Naples, it came after the death of the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg (1468) and after the conquests of Kruja (1478) and Shkodra (1479) through the Ottomans to larger waves of refugees. In the 16th and 17th centuries there were waves of migration of the Albanian-Greek population ( Arvanites ) from the numerous Albanian communities in Thessaly , Euboea , Corinth , Attica and Morea in what is now Greece . In 1742 the Christian population fled from the town of Piqeras near Lukova in Çamëria to Italy and in 1774 survivors of the last offensives of the Ottoman Empire , which were supposed to settle the vast, deserted areas near the port city of Brindisi .

In addition to their language and religion according to the Byzantine rite , the Arbëresh brought the art of iconography , their customs and costumes with them to their new homeland .

After more than five centuries in the diaspora , some of the Albanian communities founded in Italy still speak a conservative pre-Ottoman Albanian language .

Name and meaning

The Arbëresh call themselves in their Albanian dialect Arbëreshët (plural definite) or Arbëreshë (plural indefinite). The individual is called Arbëresh / -i (male) or Arbëreshe / Arbëreshja (female). The language they speak is called Arbëresh . In Italian they are called Arbëreshë ( IPA : ar'bəreʃ ).

In the Middle Ages, “Arbëresh” ( Tuscan ) and “Arbër” / “Arbën” ( Gegisch ) were the self- names of the Albanians, which became unusable during the Ottoman era. Today only the Albanians in Italy, whose ancestors immigrated from the 14th century, are called Arbëresh .

The self-designation of the Albanian people is today "Shqiptarë" ("Albanians"; plural indefinite), that of the country of Albania (Albanian indefinite: Shqipëri, certain: Shqipëria).

In ancient historical sources the Albanians are called differently: in Byzantine "Albani", in western (Naples, Venice, Aragón): "Albanians or Epiroten", in Ottoman: Arnauts and by the Greeks the Albanians living in Greece are called Arvanites.

language

The language of the Arbëresh is the old Albanian language (Arbërisht, Arbërishtja or Gjuha Arbëreshe), a sub- dialect of Tuscan (Toskë), which is spoken in southern Albania, where the mass diaspora originated. It differs significantly from today's standard language. A mixed arbëresh is spoken in some centers, consisting of a Gegic intonation (Gegë), the dialect spoken in northern Albania, with liturgical Greek (in relation to the use of religious functions) and an amalgamation with the southern Italian dialects. This process arose through the centuries of residence in Italy.

Even if today's standard language of Albania is based on the southern Tuscan dialect, the Tuscan dialect "Arbëresh" is not easily understood by an Albanian native speaker because of different accents and inflections. It is generally accepted that the level of linguistic communication among Italian-Albanians (Arbëresh) and native Albanians (Shqiptarë) is discreet. It is estimated that 45% of Arbëresh words correspond to the current Albanian language of Albania, another 15% were created by neologisms by Italian-Albanian authors and then adopted into the common language; the rest is the result of contamination with Italian, especially with the individual local dialects of southern Italy.

Because of its decreasing number of speakers, the Arbëresh is one of the threatened languages . According to an estimate from 2002, around 80,000 people speak this language. Other estimates are 260,000 (1976) and 100,000 (1987).

The younger generation speaks less and less Arbëresh, which is also due to the fact that there is no real uniform language that is spoken by all communities. As a result, the Albanians often use Italian as the language of communication among themselves .

Settlement history

Albanian settlement in Greece

The Arbëresh originally lived mainly in Epirus and in the mountains of Pindus . Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Albanian tribes moved in small groups towards the southeast to Thessaly, Euboea, Corinth, Attica and Morea, where, after an initial phase of nomadism, they were allowed to found their own colonies (katun) and their ethnic customs, such as language and Maintained tribal customs. They were and still are called Arvanites by the Greeks. They call themselves "Arbërore", which means Albanians.

The first Albanian appearance in the historical Greek region of Thessaly dates back to the late 13th-early 14th century. Mainly during the Italian rule of the Orsini (1318-1359), the population of Epirus, which consisted mainly of Albanian tribes, emigrated to Thessaly due to internal fighting, massacres and clan displacement through the valleys of the Pindus Mountains. From Thessaly, where numerous independent Albanian tribes such as Malacassi, Bua, Messariti and many others were concentrated, the Albanians were invited to Lokris , Boeotia and Attica by the Catalan rulers of the Duchy of Athens . The Albanians were considered "warlike and loyal" and as experts in the field they became popular mercenaries ( stratiotes ) of the Serbs , Franks , Aragonians and Byzantines .

The archives of the Aragonese Crown in Barcelona contain many documents that illuminate the history of the Duchy of Athens and also relate to Albanian immigration to this region. Peter IV , Count of Barcelona (as Peter I also King of Sardinia and Duke of Athens and Neopatria ) addressed himself with a thankful letter to the Count of Demetrias " e i Albanenses " (and the Albanians) for the defense of the duchies of Athens and Neopatria. On December 31, 1382, Peter IV gave his lieutenant and Viscount Rocabertino the order to grant all Greeks and Albanians who wanted to come to the Duchy of Athens a tax exemption of two years and to hand over the chapel of St. George in Livadia to Brother Francis Comminges.

Between 1379 and 1393 the Italian Nerio I. Acciaiuoli conquered the cities of Thebes and Athens with the help of a Navarre company , thus ending the Catalan rule in Greece. Since then, Catalan and Albanian refugees who were already settled in the Duchy of Athens moved to Sicily to serve the Aragonese kings of the island. On April 20, 1402 the Senate of the Republic of Venice decided " pro apopulando Insulam nostram Nigropontis " (for the settlement of our island Negroponte ) that " Albanians and others " and their families under the protection of the Republic on the island that has belonged to Venice since 1205 Negroponte (Euboea) were allowed to settle. For this they received for two years " exemption from all taxes and wasteland suitable for work " on the condition that they kept as many horses " like men of the heads of families ", were not allowed to leave the island without the permission of the Doge's Provveditore and at any time Defense of the island had to be ready.

From documents in the Archives of Venice, the organization of the Venetian governments in the various estates becomes clear: generous with the worthy and loyal subjects who have received rewards, privileges and degrees of honor and asylum in the Venetian territory in the event of an enemy invasion and strict in the application of the law with convictions and harsh sentences for guilty and criminals. Thus, on August 28, 1400, the Venetian Senate guaranteed protection and hospitality for the merits of Mirska Zarcovichio, Lord of Vlora , in the event of an Ottoman invasion. On May 14, 1406 Nicola Scura von Durazzo received a letter of recommendation from the Count of Shkodra for "untiring loyalty". Exiled for crimes, Oliverio Sguro was sentenced to death (March 27, 1451). He was to be beheaded between two pillars on St. Mark's Square in Venice (“… conducatur Venetias et amputetur ei caput in medio duarum columnarum”). On April 4, 1454, three Albanian sailors - “Balistari” - were sentenced to death in the galleys of Marino Cantareno for mutiny and desertion.

In May 1347 Manuel Kantakuzenos was by his father, Emperor John VI. Kantakuzenos , appointed Byzantine despot of Morea , where he arrived in 1349. Manuel, troubled by the wars against the neighboring Latin states, the restless population, the Ottoman invasions and the population decline, tried to remedy the demographic problem in the region by ordering the immigration of large numbers of Albanians from Epirus and Thessaly.

Theodor I. Palaiologos , despot of Morea from 1382/83 to 1406, approved the settlement of Albanian tribes in Morea between 1398 and 1404 in order to defend his despotate from Greek rebels, from Venetians and above all from the increasing number of Ottoman attacks. According to the Greek historian Dionysios A. Zakythinos , 10,000 Albanians came to the Isthmus of Corinth with their families and their own herds and asked the despot for permission to settle on the despot's territory, which the despot accepted.

Albanian colonization of Italy

With the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Albania in the 14th century, many of the then Christian Albanians fled to Dalmatia, southern Greek regions and today's Italy. With the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottomans had taken a large part of the Balkan Peninsula under their control, while the Byzantine Empire only left the coast. There are notes of migrations to Italy from the other side of the Adriatic from this period. The popular shift was primarily determined by the flourishing trade. Areas that once belonged to the Roman Empire and later to the Republic of Venice were preferred .

Republic of Venice

In the years 1388, 1393 and 1399 several alliances were forged between the Albanian princes and the Republic of Venice , which had strong commercial interests in these areas of the Adriatic. With this strategy both peoples managed to stop the conquests and expansion of the Serbs and Ottomans in these areas. It was from this web of military (stratiotes) and commercial ties that many Albanians came to Italy, and some of them stayed there and founded the first permanent Albanian settlements in the possessions of Venice.

In the 15th century Albanian emigrants were registered in Venice and in the areas under the Republic of Venice, where they formed flourishing colonies.

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples , which by its extension and fertility of its territory would have been able to accommodate twelve million inhabitants, numbered no more than five million. Over time, the government realized that efforts to increase the population were too slow and often fruitless. For this reason, the government turned to foreign countries, namely to the Albanians, who were easily persuaded to emigrate, first thanks to their proximity and then by Ottoman oppression.

It is believed that sporadic Albanian groups came to the Kingdom of Naples as early as the 13th and 15th centuries. There are reports of Albanians in Calabria who were in the service of the feudal Calabrian barons after the port city of Durazzo (Latin Dyrrachium) was conquered by the King of Sicily , Charles I , in 1272. They rose up against the Angevin regime because of excessive forks and other taxes that were impossible to pay and called on the Albanians for help, who made their military services available.

Charles I issued advantageous regulations for the Albanians who were in Apulia. From the year 1272 there are traces of Albanians in a place called Pallavirgata near Brindisi, others in various places in the province of Terra d'Otranto , of which, however, all trace has been lost. Merchants received tax breaks, many of whom had been invited by the local masters to Apulia, Calabria and Sicily to do business there.

Among the Albanians in the Kingdom of Naples there were also so-called “ obsides ” or hostages, “obviously people of high rank who were guests in Aversa ”, as well as “some prisoners in the fortresses of Brindisi and Acerenza ”. When Charles I confirmed their "privilegia antiquorum Imperatorum Romaniae" to the citizens of Durazzo on February 20, 1272, the Albanian chiefs provided six hostages as a guarantee of their loyalty, who were interned in Aversa on December 13, 1274. Also mentioned are some enslaved "Albanenses seu Graeci" (Albanians or Greeks), people from the Balkans of both sexes who were kept as "sclavis seu servis" (slaves or servants) due to the fact that they had been bought. King Charles I gave the order that these "Albanenses et Graecos masculos seu feminas" (Albanians and Greeks male or female) be liberated and go wherever they wanted.

When Karl Thopia conquered the Principality of Albania in 1368 , many Albanian supporters of the Queen of Naples, Johanna I , had to flee to the Kingdom of Naples to escape the reprisals of the new master.

Under Martin I. , of Sicily (1401-1409), served for many years of the king of Epirus originating Giovanni Matrancha (also: Matracca, Matraccha, Matracchia, Matranga) that as a reward for his services to the field of Morgana not far from Calascibetta located and received the royal stewardship of Castrogiovanni . In 1391 he married the noble Giacopina Leto in Castrogiovanni, with whom he had two sons: Giacomo and Pietro. The brothers, who in 1406 inherited a large area called Marcato di Mulegi , from Antonio di Ansisa, a relative on the mother's side, “lived very richly”, especially Giacomo, who acquired the Mantica fief and other goods. An old tomb inscription in the Chiesa Santa Caterina in Castrogiovanni of the commandant Giacomo Matrancha, Baron von Mantica and other fiefs, gives certainty about this: “Hic iacet Jacobus Matrancha, olim Baro Manticae cum suis ab Epiro, post infinitos labores, spiritum inter sidera suisque ossibus, hic iacet Jacobus Matrancha, olim Baro Manticae cum suis ab Epiro, post infinitos labores, spiritum inter sidera suisque ossibus requiem dedit "

Historically significant for the Albanian principalities was the battle of the Amselfeld on June 15, 1389, in which some Albanian princes such as Pal Kastrioti and Theodor Muzaka II took part. Both fell in this battle. The battle on the Blackbird Field marked both the beginning of the Ottoman conquest of the Balkan Peninsula and the beginning of a strong defense of the Albanian population, which would not come to an end until 100 years later. During this time the first Albanian refugees settled in southern Italy.

Under the Spanish Aragonese (1442–1501, 1504–1555), the Habsburgs (1516–1700, 1713–1735) and the Bourbons (1735–1806), the Kingdom of Naples was a center of military activity and colonization for Balkan peoples.

While the Republic of Venice also entered into trade relations with the Ottomans, the representatives of Spain in southern Italy always showed a hostile attitude towards the Ottomans. They never allied with them (until the mid-18th century) and were unable to create commercial interests of any kind in the eastern Mediterranean and other sultans' territories .

Despite the opposition from Venice, the Spaniards did not hide their efforts to expand their political influence to the nearby Balkan Peninsula . Both in relation to this tactic and in view of the general policy of Madrid, the viceroys of Naples and Sicily always had to have strong armed forces ready, ready on the one hand to avert possible uprisings by the local barons and on the other hand to pose the uninterrupted Muslim threat to stop the Balkans. Due to the Muslim threat in particular, strong naval units had to be maintained to repel the centuries-long attacks (from the 16th century to the beginning of the 19th century) by the North African Muslim pirates on the kingdoms (Sicily and Naples), Sardinia and the eastern Iberian Peninsula to withstand a possible Ottoman invasion, which since the time of the conqueror, Mehmed II (1444–1446, 1451–1481), always hung like a sword of Damocles over the Calabrian and the adjacent coastal strip. The Greeks and Albanians who lived in the Kingdom of Naples (and, to some extent, those of Sicily as well) thus found the opportunity to engage in the Sicilian Navy or in the Neapolitan light cavalry (Stratiotes), and in doing so fulfilled a double function Need: to be paid well by their Spanish superiors and to let their hatred of the Ottomans run wild.

Most of the colonies were founded in southern Italy after the death of the Albanian prince Gjergj Kastrioti, called Skanderbeg (1468), the Ottoman conquests of Kruja (1478), Shkodra (1479) and Durrës (1497). These waves of immigration continued until 1774 when a colony of Albanians settled near the port city of Brindisi in Puglia.

According to historical studies , there were nine waves of emigration from Albanians to Italy, to which must be added internal migration within southern Italy and the last migration (the tenth) in the 1990s.

The Arbëresh established nearly 100 soldiers and farmers colonies, most of which are in Calabria. They received privileges such as tax exemption and full administrative autonomy. It was later introduced that each Albanian "fire" had to pay eleven Carlini (medieval coin in the Kingdom of Naples) annually. An exception was Calabria Citra, where the prominent people of Koroni in Morea had settled that on April 8, 1533 by the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire , Charles V had received special privileges (see below: The fifth migration). These privileges were exceptional, but were extended to the places Barile and San Costantino Albanese in Basilicata and Farneta in Calabria, because "Coronei" (Italian for the population of Koroni) lived there. The privileges were permanent and were later confirmed: on July 18, 1534 by Charles V, which was confirmed by the Royal Chamber on March 3, 1538. At the request of the descendants of the "Coronei" who settled in the kingdom, the privileges with the date Madrid, July 20, 1620, and with the clause "dummodo in possessione existant" (presumed alive) were granted by Philip III. approved. Among other things, Philip III allowed. Carrying the "Coronei" weapons everywhere, even into the prince's apartments. Thus they became "Lance Spezzate" ( Lance Corporal ) of the King of Spain. In confirmation of the capitulations between the “Coronei” and the rulers, one reads: “Likewise, these citizens can carry weapons throughout the empire and in the jurisdiction of the aforementioned imperial messieurs, even into the chamber of their messieurs and their officers, as the previous ones kings have granted [...]. "on August 20, 1662 (enforced on 25 August 1662) the privileges of were Philip IV. with the clause" dummodo in posse immersione existant "and finally by Philip V confirmed.

In 1569 one counted 3944 Albanian “fires”: in Molise 102, in Principato Ultra 56, in Basilicata 787, in Calabria Ultra 153, in Terra Hidrunti 803, in Terra di Bari 1186, in Capitanata 1169, in Abruzzo Ultra 138, in Abbruzzo citra 403. There is no census of the other provinces for this year, as it often happened that the Albanians moved away in order not to be counted and thus the eleven Carlini did not have to pay each year.

With the marriage of Irina (sometimes referred to as Erina, Irene or Elena) Kastrioti (granddaughter of Gjon Kastrioti II, the son of Skanderbeg), daughter of Ferdinand (Duke of San Pietro in Galatina and Soleto ), in 1539 with Pierantonio Sanseverino († 1559 in France), Prince of Bisignano , Duke of Corigliano Calabro and San Marco , there was internal migration. Many Arbëresh from Apulia followed her to Calabria, where they are said to have founded Falconara Albanese in the province of Cosenza .

The first migration (1399–1409)

The first migration took place between 1399 and 1409, when the King of Naples, Ladislaus from the French house of Anjou , was forced to fight the uprisings of the local barons in Calabria with Albanian mercenary troops who offered their services to one party or the other , which belonged to the Kingdom of Naples, against the Anjou. At that time there were often revolts of the nobility against a royal power willing to compromise.

The Second Migration (1461–1468)

The third migration goes back to the years between 1461 and 1468, when Ferdinand I from the Spanish house of Aragon , King of Naples, was forced to ask Skanderbeg for support in the fight against an uprising of the local barons fought by the French Anjou ( 1459–1462) .

Skanderbeg, who was involved in battles with the Ottomans, entrusted his nephew Coiro Streso (or Gjok Stres Balšić ) with a 5000-strong expeditionary force.

His operations were based in Barletta . The troops of the rebel Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo , last Prince of Taranto , were quickly defeated. Then there was a battle with the French and the capture of the city of Trani .

In 1460 King Ferdinand had serious problems with another uprising by the Angevin and asked Skanderbeg again for help. This request worried the opponents of King Ferdinand. The pre-eminent but unreliable condottiere Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta , the wolf of Rimini , stated that if Ferdinand Skanderbeg were received, he would defer to the Ottomans. In September 1460 Skanderbeg sent a company of 500 cavalrymen under his nephew Ivan Strez Balšić , who arrived in Trani and Barletta on October 1, 1460.

Ferdinand's main opponent, Prince Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo of Taranto, tried to dissuade Skanderbeg from this venture and even offered him an alliance, which had no influence on Skanderbeg, who replied on October 31, 1460 that he was part of the Aragon family, especially in the times of the Distress, fealty is owed. In his reply to Orsini, Skanderbeg mentioned that Albanians would never tell their friends that they were descendants of Pyrrhus of Epirus , thus reminding Orsini of the Pyrrhic victories in southern Italy .

When the situation became critical, Skanderbeg concluded a three-year armistice with the Ottomans on April 17, 1461 and reached Apulia on August 25, 1461 with an expeditionary force of 1000 cavalrymen and 2000 infantrymen. Ferdinand entrusted him with the entire Apulian front and with the defense of the fortress of Barletta, while the king fought further north with Alessandro Sforza , lord of Pesaro, against the French Anjou.

Skanderbeg carried out the assigned task with the utmost conscientiousness. From Barletta and Trani he attacked the territories of the rebel barons in Terra d'Otranto, where he spread misery and devastation. The "Casali", castle of Mazara, in the province of Taranto, whose feudal lords were allied with the rebel Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo, were destroyed.

After three months, the rebels, led by the Prince of Taranto, demanded peace, for which Skanderbeg himself acted as a mediator.

Skanderbeg later fought in the battle in the Terrastrutta area, near what is now Greci in Campania, in which the Anjou were finally defeated. After this battle a garrison of Albanian soldiers was left on this hill to defend against possible rebel incursions, who founded the town of Greci.

Skanderbeg had managed to defeat the Italian and Angevin troops of Orsini of Taranto, secure the throne of King Ferdinand, and return to Albania. King Ferdinand thanked Skanderbeg for the rest of his life. While a large part of the troops stayed in Apulia and settled in Capitanata and Terra d'Otranto and founded " Albania Salentina " ( Salentine Albania), Skanderbeg returned home with some troops to again face the Ottomans.

The " Albania Salentina " included the towns of Sternatia and Zolino in the province of Lecce , Belvedere (extinct), Carosino , Civitella (Carosino) , Faggiano , Fragagnano , Monteiasi , Montemesola , Monteparano , Roccaforzata , San Crispieri , San Giorgio , San Martino (extinct ) and Santa Maria della Camera (today part of Roccaforzata) in the province of Taranto, of which today only San Marzano di San Giuseppe represents the historical memory of those times and has received the Albanian dialect Arbëreshët. In the province of Foggia in Capitanata, Casalnuovo Monterotaro , Casalvecchio di Puglia , Castelluccio dei Sauri , Chieuti , Faeto , Monteleone di Puglia , Panni and San Paolo di Civitate were founded.

On Skanderbeg's trip to Naples in 1467, Ferdinand I fulfilled his “gratitude, generosity and benevolence” for the help he received in Apulia with a charter on April 10th . Skanderbeg received for himself and his current and future heirs the feudal estates Trani , Monte Sant'Angelo and San Giovanni Rotondo in Capitanata with a number of symbolic and economic advantages: the extension of power to the entire stretch of coast between the two estates, the direct access to the royal jurisdiction in the event of disputes and finally the possibility of importing and exporting goods of any value from the coast of Monte Sant'Angelo and the port of Mattinata without any obligation to pay the fees to the port of Manfredonia . Monte Sant'Angelo was a very respected fief at the time, which until then had only been granted to members of the ruling house.

Since the charter was only to be valid after three years, the king swore the oath of allegiance four days later .

Many of the Albanians who had accompanied their prince to Italy asked and were given the right to be allowed to stay with their families where they were scattered in different places.

After Skanderbeg's death on January 17, 1468 in Lezha , his widow Donika Arianiti expressed to King Ferdinand I of Naples the desire to be able to settle with her son Gjon Kastrioti II , the only descendant of Skanderbeg, on the fiefs of Skanderbeg in the Kingdom of Naples to escape the revenge of the Ottomans and Islamization, which the king accepted with joy in his letter of February 24, 1468.

The third migration (1468–1506)

The fourth and most extensive migration goes back to the years between 1468 and 1506, when the Venetians left the Albanians to the insatiable languor of Mehmed II for more territory. More and more Albanian cities and fortresses fell under Ottoman rule. The population was persecuted and slaughtered. Many Albanians, who foresaw the entire occupation of their homeland and the revenge of the Ottomans, followed the example of those Albanians who had previously settled in southern Italy. From the ports of Ragusa , Skutari and Lezha they left their homeland on Venetian, Neapolitan and Albanian ships.

Pope Paul II wrote to the Duke of Burgundy: “The cities [of Albania], which up to this day had withstood the wrath of the Turks, have from now on fallen into their power. All the peoples who inhabit the shores of the Adriatic Sea tremble at the sight of the impending danger. One sees only horror, sadness, imprisonment and death everywhere. It is not without tears that one can see those ships that flee from the Albanian coast into the ports of Italy, those naked, wretched families who, driven from their homes, sit on the shores of the sea with their hands stretched out to the sky and the air with wailing in fulfill a misunderstood language. "

Many of the Albanians who were able to flee to Italy were given land and citizenship by the local feudal lords in sparsely populated areas. They settled along the Adriatic coast between Abruzzo and the Gargano foothills , and later moved on to Molise and the Papal States, where some settled in Genazzano . Others went ashore in the Marche , where they stayed in Urbino and other places in central Italy; almost all memory of these has been lost.

More information is available from those who moved to the Kingdom of Naples and selected mountainous areas around Benevento (today in Campania ) and Barile (1477) and Melfi (today in Basilicata ), where they found dilapidated houses, abandoned and devastated places, often old too Settled abbeys. Still others went ashore in Calabria, where they found Lungro, Firmo , Macchia Albanese , San Cosmo Albanese , San Demetrio Corone , San Giorgio Albanese , Santa Sofia d. In the province of Cosenza near Corigliano Calabro on the slopes of the Sila massif 'Epiro , Spezzano Albanese and Vaccarizzo Albanese founded. Others preferred to settle on the heights of the Ionian Sea from the Sinni to the Crati , from Cosenza to the sea. Some families of the old nobility went ashore in Trani and Otranto. Mention should be made of the Basta family, who became famous and powerful in Genoa and Venice. In 1759 Ferdinand IV. Attributed the family to the nobility of Taranto with a special document. A Giorgio Basta was captain and baron of Civitella and Pasquale Teodoro Basta (born April 26, 1711 in Monteparano , † December 27, 1765) was elected bishop of Melfi and Rapolla on January 29, 1748 .

After the conquest of Kruja (1478) and Shkodra (1479) by the Ottomans, there was another flight of Albanian nobles to the Kingdom of Naples to escape the revenge of the Ottomans and Islamization. Many Catholic Albanian families with the Byzantine rite followed their compatriots and founded the "Casali" Acquaformosa , Castroregio , Cavallerizzo (today a fraction of Cerzeto ), Cervicati , Cerzeto, Civita , Frascineto , Marri (today a fraction of San Benedetto Ullano ) in the province of Cosenza , Mongrassano , Percile , Plataci , Rota Greca , San Basile , San Benedetto Ullano, Santa Caterina Albanese , San Giacomo di Cerzeto (today fraction of Cerzeto), Serra di Leo (near Mongrassano) and many other places of which in the meantime the Traces have been lost.

Others settled in Sicily under royal charter, where they moved to the settlements founded by the soldiers of Reres in 1448. But new settlements were also established: Palazzo Adriano was founded in the province of Palermo in 1481 , Piana dei Greci in 1488 , Mezzojuso in 1490 and Santa Cristina Gela in 1691, and Biancavilla in the province of Catania in 1488 . For a living, some worked in agriculture or cattle breeding and others in the army of the Catholic Ferdinand II , King of Sicily. Among them are Peter and Mercurio Bua, Blaschi Bischettino, Giorgio and Demetrius Capusmede, Lazarus Comilascari, Giorgio Matrancha (junior), Biaggio Musacchio from the famous Musacchi family (princes and despots of Epirus), Cesare Urana (Vranà), and other famous soldiers and captains, who with their martial arts served Emperor Charles V in the Tunis campaign (1535), in the wars in Italy and in the siege of Herceg Novi (1537–1540).

Johann , King of Sicily from 1458 to 1468, recommended in a letter to his nephew Ferdinand I , King of Naples, the Albanian nobles “Peter Emmanuel de Pravata, Zaccaria Croppa, Petrus Cuccia and Paulus Manisi, tireless opponents of the Turks and the most energetic and most invincible leader Georgi Castriota Scanderbeg, Prince of Epirus and Albania, and his relations with other aristocratic Albanians ”and allowed the“ passing ”Albanians to settle in Sicily. He exempted them "from any collection, taxation and royal imposition and this for life only for the aforementioned De Pravata, Croppa, Cuccia, Manisi and other Excellencies". The Albanians in the other provinces of the Kingdom of Naples received the same privileges as those in Sicily.

After the conquest of Kruja in 1478, the first Albanian refugees (Arbëresh) came to the Brindisi Montagna area . Proof of this is the street naming of the municipality that dedicated Via dei Crojesi to these refugees.

The Albanians were accepted as martyrs of the Christian religion because they had fought against the Ottomans for decades and thus slowed down the Ottoman invasion of Europe and because famines, epidemics and earthquakes - like the catastrophic one of 1456 - had depopulated the Italian regions, which made the landlords possible to offer beneficial privileges to refugees such as tax halving.

The fourth migration (1532-1534)

The fifth and last massive migration goes back to the years 1532/34, when the Ottomans conquered the fortress Koroni in Morea and the Greek and Albanian population living there fled from Koroni, Methoni , Nafplio and Patras to the Kingdom of Naples.

The starting point was the port city of Koroni, which together with Methoni had played a key role in the history of trade and the Venetian-Byzantine relations in the 11th century.

Koroni was conquered in 1200 by the Genoese pirate Leo Vetrano (d. 1206), fell into the hands of William I of Champlitte , participant in the Fourth Crusade , in 1205 , and was ceded to the Venetians by Gottfried von Villehardouin in 1206 , where it was up Remained at the end of the 15th century. By 1460 the Ottomans had conquered most of Morea. Because of the impossible defense against the Ottomans, the city was left to its own devices.

Located on the western southern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula, Koroni and Methoni were considered incomparable observation posts, which as "venetiarum ocellae" (eyes of the Republic of Venice) for centuries monitored the routes of the galleys to Crete , Constantinople and the Holy Land and where all ships that returning from the east had a duty to stop to report on pirates and convoys.

In Koroni existed since the 12./13. In the 18th century a large Albanian minority of the Greek Orthodox faith, called Arvanites by the locals. In the 15th century, a large number of Albanian princes who had fled their homeland before the Ottomans found refuge there.

At the end of August 1500, Sultan Bayezid II conquered the city and the castle. When the Ottomans under Sultan Suleyman I made a second attempt to conquer Vienna in 1532, the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria , who was in Spanish service, defeated the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (as Charles IV, King of Naples) the House of Habsburg a diversionary maneuver on the Greek side. The emperor accepted and gave Doria the assignment for the expedition. On July 29th Andrea Doria arrived in Naples with 25 galleys and on August 4th Doria arrived in Messina, where he was waiting to join several ships to set off. On August 18, Andrea Doria's fleet with 48 galleys and 30 large ships left the port of Messina to the east. His team consisted of locals and mostly Albanians who immigrated after Skanderbeg's death. It is reported that Doria was warned by the Venetians that the Ottomans were at Kefalonia with an insignificant fleet . At the same time, the Venetians warned the Ottoman admiral about the arrival of Doria and his large fleet. But when Doria came to the place indicated, the Ottoman fleet had withdrawn to Constantinople. Doria devastated the beaches of Greece and decided to attack Koroni.

When Doria's arrival in front of Koroni, the local people secretly sent him messages to welcome him, to inform him about the internal state of the city and to declare that they were ready to cooperate from within. Andrea Doria had a large part of the Spanish and Italian crew put ashore to siege the city. The Italians were commanded by Girolamo (or Geronimo) Tuttavilla and the Spanish by Girolamo Mendoza. After a stubborn three-day struggle and the death of "300 Christian soldiers", Doria took what was then the metropolis of Morea on September 21, 1532. Now the townspeople identified themselves, took sides with him, as previously agreed, and proclaimed the sovereignty of Charles V. But the property was not secured because the Ottoman garrison locked themselves in the fortress. The next day, however, the Ottoman General Zadera returned with 700 cavalry soldiers to help the Ottoman soldiers. The Spaniards and the population of Koroni prepared for battle, killed a large number of the Ottomans, planted the heads of the slaughtered on their lances, while those entrenched in the fortress surrendered to Admiral Doria. In this victory, in which the "Coronei" had distinguished themselves with daring, the admiral and the Spaniards accompanied endless applause.

When Doria left the city to conquer Patras, he entrusted the city government to Don Girolamo Mendoza. After the news of the conquest of Koroni and the massacre of an astonishingly high number of Ottoman soldiers had reached Suleyman, Suleyman swore bitter revenge on the "Coronei", authors of this misfortune who had joined the Spanish crown.

On November 8, 1532, Emperor Charles V had Admiral Doria recalled from the east. The most important Von Koroni families embarked on Doria's ships and arrived with him on December 24th in Naples, where Doria received much praise.

Charles V honored the "loyal and courageous" Albanians from Koroni and Patras with several certificates and showered them with privileges. In the form of a letter dated April 8, 1533, he entrusted them to the Marquis of Villafranca and Viceroy of Naples, Pedro Álvarez de Toledo , called them "Cavalieri" (= knight; Italian nobility title), freed them from any tribute and granted them annually 70 ducats from the treasury of the empire:

“Honored Marquis, our first viceroy, lieutenant and captain general. As you can see from our letter, We have agreed that some soldiers from Koroni, Patras and Çameria will settle in this realm so that if they stay they will be offered an offer of service; with the order that you assign them a few places in Apulia or in Calabria or in other parts of the Empire where they can live and provide for their livelihood; see to it that they are free from any tax payment until We decree otherwise, so that they can eat better […] and that with Our consent they are paid seventy ducat coins every year from Our treasury of this realm. "

This privilege had its full effect for a long time and was confirmed again and again. While the Albanians were later taxed annually at eleven Carlini per “fire” in the other provinces, the “Coronei” in Calabria Citra were not counted. The king also ordered them to be given land in Apulia, Calabria, or other provinces of the kingdom. Some settled in Barile in Basilicata, in San Benedetto Ullano and in San Demetrio in the province of Cosenza. However, they all received 70 ducats from the royal treasury annually for their maintenance. With another document dated May 10, 1533, Charles V raised the "Coronei" to the nobility. Last names such as Jeno dei Nobili Coronei, Rodotà dei nobili Coronei, Camodeca dei Nobili Coronei etc. bear witness to this. With a deed of July 15, 1534, the king exempted the "Coronei" from all royal and baronial taxes as well as transit and hull taxes (tax for the Construction of ship hulls).

The Spanish flag was not to fly long on the fortress of Koroni, because in 1533 Suleyman sent a sea fleet under the commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Mediterranean navy Khizir , known by Christian Europeans as Barbarossa, in front of the city. Mendoza, who found himself surrounded, sent a message to the Viceroy of Naples , Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, asking for immediate help. The "Coronei" also added their concern and expressly emphasized their dismay in order to receive the desired support. The viceroy sent both letters to the emperor who, from the representations of one and the other, "was sensitive and respectful of the nobles from Koroni who had campaigned for the good of the royal crown", and quickly a new sea fleet with 150 galleys under the direction of Andria Sent Doria to Koroni. Eight nautical miles from Koroni, on August 2, 1533, there was a brief battle with the Ottomans. Doria left a garrison under the command of Rodrigo Machicao , had supplies brought ashore, returned to Naples with Girolamo Mendoza and disbanded the army.

With the peace treaty signed in Constantinople between Charles V and Suleyman I, the fortified city of Koroni was left to the Ottomans. One of the conditions was that the "Coronei" who wanted to leave the city could embark on a fleet specially sent by Charles V in order to find refuge in Italy. 200 merchant ships chartered by the Neapolitan government sailed to disembark all Koroni Greek and Albanian families who preferred to find a new home in the southern provinces of Italy. Around 2000 people "with their archbishop according to the Greek rite, Benedict", mainly soldiers, were saved "at their own expense in good time from the anger of the Ottomans" and transported to the coasts of the Kingdom of Naples. This group was led by the stratiot captain Lazzaro Mattes (or Lazaro Mathes).

Some moved to Lipari , others preferred to join their compatriots from Morea in Sicily, others spread to provinces on the mainland. Charles V gave Lazaro Mathes and his heirs and successors permission to found "Casali" in the Kingdom of Naples. The vassals who were involved in the construction and their descendants should be exempt from paying taxes. Lazaro Mathes was responsible for the founding or repopulation of the towns of Barile, Brindisi Montagna , Ginestra, Maschito, Melfi , San Costantino Albanese, San Paolo Albanese and San Giorgio Lucano in the province of Potenza in Basilicata and of Castroregio and Farneta in the province of Cosenza in Calabria . Another group founded or repopulated Greci in the province of Avellino. With the concession of Charles V, Mathes let various dilapidated " Casali " in the area of Taranto (San Martino, Roccaforzata) populate. Others settled in Naples, the capital of the kingdom, where, in addition to the total tax exemption, they received an “appropriate maintenance of 5000 ducats” annually from the state treasury and the Cappella dei SS. Apostoli founded in 1518 by Thomas Assan Palaiologos for the Greek community (today : Church of Santi Pietro e Paolo dei Greci ) so that they could practice their faith in the Greek rite.

On July 18, 1534, Charles V confirmed out of gratitude to the "loyal and loyal Coronei", whose city is "in the hands of Turkish people and they are now coming into the kingdom without their possessions and with the request to live here", the privilege of tax exemption of April 8, 1533:

“[…] We, in view of their prayers, we are kindly inclined to accept these people and decree tax exemption for all“ Coronei ”in this kingdom, which is completely and inviolably followed and carried out and to use and enjoy the promised tax exemption [...] ”. The decree was ratified by the Royal Chamber on March 3, 1538.

The fifth migration (1600–1680)

The exact date is not known. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Duke of Parma and Piacenza Ranuccio I from the Farnese family is said to have taken in Albanian refugees in the province of Piacenza , who were settled in Boscone Cusani (today a fraction of Calendasco ). At the same time, the localities of Bosco Tosca were populated by southern Albanians and Pievetta (today fractions of Castel San Giovanni ) by northern Albanians.

When the Greek-Albanian population of Mani in Laconia on the Morea Peninsula rebelled against Ottoman rule in 1647 and the uprising was violently suppressed, there was another wave of emigration.

A document dated May 14, 1647 states that “the Greek bishop who came here [Naples] to negotiate the passage of 45,000 maniots into this kingdom [Kingdom of Naples] because of disproportionately high demands without having achieved anything , returned to Maina ”.

On June 16, 1647, a considerable number of maniots arrived in Otranto “who have come with their families to live in this kingdom”. According to the contract modality of the Viceroy (Rodrigo Ponce de León (IV)), which he allowed himself to be granted by the royal court and the barons, and the ambassadors of the province of Mani, the maniots were to be exempt from tax on houses where they lived for ten years and get land. It was also reported that around 6,000 more maniots were due to arrive. Most of the maniots settled in Barile in the province of Potenza in Basilicata, where as early as 1477 after the conquest of Kruja, in 1534 "Coronei" and 1597 about 30 families, "Coronei" from Melfi, had settled. The settlement of the maniots emerges from a manuscript by Don Giuseppe Caracciolo , 1st Prince of Torella from 1639 to 1670. The new settlers established themselves on the top of the southernmost hill, separated from the first hill by a stream.

The Albanian population of Barile, who practiced the Greek rite until the mid-17th century, was persuaded to follow the Roman rite by the Bishop of Melfi.

In 1680 some Arvanite families fled Maina, led by the brothers Georg and Macario Sevastò, the first priest and the other Basilian monk . Monsignor Ferdinando Apicella placed them in Chieuti.

The sixth migration (1743)

The seventh migration dates back to 1743, when the then Spanish Charles VII of Naples-Sicily took in Greek-Albanian families (a total of 73 people) from the coastal town of Piqeras, a place between Borsh and Lukova in Çamëria, in the Kingdom of Naples .

This emigration was preceded by an attack by the people of Borsh and Golëm in Kurvelesh, who had converted to Islam , in December 1742, after which the community decided to leave their hometown under the care of their Albanian papa Macario Nikàs (Nica) and the deacon Demetrio Atanasio. On their way via Lukova , Shën Vasil, Klikursi, Nivica-Bubar , north of Saranda , Corfu and Othoni , other families joined them.

The 18 families in total reached Brindisi in the then Kingdom of Naples in June 1743 , from where Charles VII had them transported to the Abruzzo region in October 1743 at the expense of the Crown . In Pianella they were waiting to be settled somewhere. After disputes with the long-established population there, who did not accept the immigrants, King Karl decreed and signed the document of the state concession to the Albanians in Piano di Coccia and in Badessa, today's Villa Badessa, on March 4, 1744. The exact date of the arrival of the immigrants in Badessa can be found in an old baptismal register from which it emerges that the first baptism was performed on November 18, 1743.

The Seventh Migration (1756)

In order to avoid religious persecution in the Ottoman homeland of Albania, some Catholic families from Shkodra reached Ancona in April 1756 to seek refuge in the papal state . After Pope Benedict XIV provided them with everything they needed and money from the apostolic treasury, he ordered the general economist of the Apostolic Chamber to accommodate them in Canino , to provide for their food and land available to the heads of families in the area of Pianiano (today a parliamentary group von Cellere ) in the province of Viterbo in the Lazio region .

The eighth migration (1774)

According to Tommaso Morelli, the ninth migration goes back to the year 1774 when the Spanish Ferdinand IV , son of Charles VII , was king of Naples . Under the condition of cultivating and settling in the vast, already deserted lands near the port city of Brindisi, the king promised them three carlini a day. The head of this group was the learned man Panagioti Caclamani, called Phantasia from Lefkada , who was under the tax authorities , Marquis Nicola Vivenzio (* 1742 in Nola ; † 1816 in Naples). Although Caclamani was a cafetier by trade, he was well read and proficient in the Greek language. He was a student of the priest Giacomo Martorelli (born January 10, 1699 in Naples, † November 21, 1777 in the Villa Vargas Macciucca in Ercolano ).

However, the colony did not live up to the government's expectations and the large sums that had been paid out. The new settlers were without craft and “were nothing but vagabonds” who were lured to the Kingdom of Naples by the generous payment of three carlini a day. Before long, the new settlers were cheated of their wages by their superiors. They went en masse to the capital, Naples, to ask the ruler for patronage. Ferdinand IV handed her complaints to a special commission headed by Nicola Vivenzio. The king also ordered that the Archimandrite Paisio Vretò, chaplain of the 2nd Real Macedonia Foreign Regiment, should work together on such a matter . The chaplain’s loyalty to the king and his zeal towards his countrymen were well known to the ruler. In fact, they soon received part of their arrears payments.

However, the appearance in Naples and the death of their leader Phantasia were the reason for the dispersion of this colony. It is not known whether it was the above-mentioned place Pallavirgata.

The ninth migration

The tenth migration is still ongoing and cannot yet be considered complete.

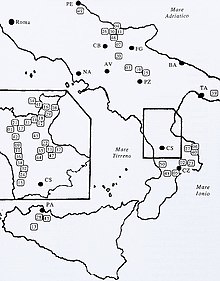

Settlement areas

The settlement areas, the totality of scattered places of the ethnic Albanian-speaking minority in seven regions in central and southern Italy as well as in Sicily, are called " Arbëria " (also: Arberia) in Italian . One recognizes the Albanian places by the retention of their original language. They have two nomenclatures , Italian and Albanian (in the Arbëreshë variant). Today there are still 50 places of Albanian origin and culture, 41 municipalities and nine fractions with a total population of more than 100,000 inhabitants, which are protected by Law No. 482 “For the Protection of Historical Language Minorities” of December 15, 1999.

There is no reliable data on the actual number of Italo-Albanians. The last statistically reliable data are those of the 1921 census, when 80,282 Albanians were recorded, and that of a 1997 study by Alfredo Fernandes that puts a population of around 197,000. In 1998 the Italian Ministry of the Interior estimated the Albanian minority in Italy at around 98,000 people.

There are also more than 30 former Albanian centers that have lost their Albanian historical and cultural heritage in various historical periods and for various reasons. From North to south:

-

Emilia-Romagna :

- in the province of Piacenza : Boscone Cusani, Bosco Tosca and Pievetta, fractions of Castel San Giovanni

-

Lazio :

- in the province of Viterbo : Pianiano , fraction of Cellere

- Molise:

- Campania:

- in the province of Caserta : Alife

- Apulia:

- in the province of Foggia: Casalnuovo di Monterotaro , Castelluccio dei Sauri and San Paolo di Civitate

- in the province of Taranto: Monteparano, San Giorgio Ionico, San Crispieri, Faggiano, Fragagnano Roccaforzata, Monteiasi, Carosino and Montemesola

- Basilicata:

- in the province of Potenza: Brindisi Montagna and Rionero in Vulture

- in the province of Matera: San Giorgio Lucano

- Calabria:

- in the province of Cosenza: San Lorenzo del Vallo , Serra d'Aiello

- in the province of Catanzaro: Amato , Arietta (fraction of Petronà ), Zagarise

- in the province of Crotone: Belvedere di Spinello

- Sicily:

- in the province of Agrigento : Sant'Angelo Muxaro

- in the metropolitan city of Catania : Bronte and San Michele di Ganzaria

There are also larger Arbëresh communities in Milan , Turin , Rome , Naples , Bari , Cosenza , Crotone and Palermo . Diaspora communities in the United States , Canada , Argentina and Brazil also maintain their cultural and linguistic origins .

Culture

Today there are many places that have managed to preserve not only their Albanian language and their manners and customs, but also their Byzantine rite in Greek and Albanian, which also provides for the maintenance of certain peculiarities such as the ordination of married men.

Even today, the Arbëresh wear their traditional costumes on festive occasions. The belt buckles of the women are particularly noteworthy because of their elaborately handcrafted metalwork and mostly show St. George , the patron saint of Arbëresh.

religion

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, many Albanian princes returned to the Catholic Church and directed their politics more and more towards the west, which led to an open uprising with the Byzantine , Serbian and Ottoman supremacy, which in the areas under them tended to be Greek -forcing orthodox and muslim religions.

Some of the Albanians who came to Italy were already in tune with the Catholic Church; the others, once in Italy, remained stubbornly attached to their Byzantine religious identity. Until the middle of the 16th century, these communities had constant relations with the Patriarchate of Ohrid ( Macedonia ), to which they belonged.

With the papal bull of January 26, 1536, Pope Paul III confirmed . the Bull of Pope Leo X of May 18, 1521 for the Greeks in the Venetian territory and gave the Albanians in Italy full recognition within Catholicism . During the pontificate of Pope Clement XI. (1700–1721), who was of Albanian origin, and that of Clement XII. (1730–1740) there was a repeated interest on the part of the Holy See in the Byzantine tradition. In October 1732 the “Collegio Corsini” in San Benedetto Ullano (Greek parish under the authority of the Bishop of Bisignano) was created, a university whose aims were very specific. She was supposed to provide education, instruction in classical literature and in the philosophical and theological sciences, as well as training young Italo-Albanians, prospective priests of the Byzantine rite, to meet the spiritual needs of the Albanians of the Kingdom of Naples and the missions of the Eastern Greeks . With the establishment of the college with Byzantine rite, Pope Clement XII decreed. the Greco-Byzantine rite on Italian soil.

However, the Italo-Albanian bishop did not yet have his own diocese and the unity of the parishes with the Byzantine rite was missing. Therefore the Arbëresh parishes were assigned to the local Roman Catholic bishops of the Latin dioceses: Cassano , Rossano and Bisignano in Calabria; Anglona in Lucania ; Lecce in Apulia and Penne in Abruzzo. This meant, among other things, the lack of respect for the Greek minority church. On February 13, 1919, Pope Benedict XV founded with the Apostolic Constitution Catholici fideles the Greek-Catholic Diocese of Lungro in the province of Cosenza, which united the 29 Italian-Albanian parishes with Byzantine rite in southern Italy. It was the first Catholic diocese with a Byzantine rite on Italian soil. With the bull Apostolica Sedes by Pope Pius XI. On October 26, 1937, the Eparchy Piana degli Albanesi was established for the Italo-Albanian communities with Byzantine rite in Sicily.

The main characteristic of the Byzantine rite is to obey the divine liturgy of St. John Chrysostom both in the Eucharistic liturgy and in the celebration of the other sacraments (e.g. the ritual of baptism has been maintained by immersion ). Another feature of this rite is that church celibacy is not compulsory for priests, so that married men can also be ordained.

Many of the communities where Arbëresh is still spoken have lost the Byzantine rite over the centuries. This came under pressure from the religious and civil authorities at the local level. Around half of the Arbëresh communities converted to the Latin rite in the first two centuries . The Byzantine rite is mainly held in the Arbëresh communities in the province of Cosenza , in Calabria and in those around Piana degli Albanesi in Sicily.

- List of parishes where Arbëresh is still spoken, which has changed over to the Latin rite

- Molise : Province of Campobasso : Campomarino , Montecilfone , Portocannone , Ururi

- Campania : Avellino Province : Greci

- Apulia :

- Basilicata : Province of Potenza : Barile , Ginestra , Maschito

- Calabria:

- Province of Catanzaro : Andali , Caraffa di Catanzaro , Gizzeria , Marcedusa , Vena di Maida ( Maida ), Zangarona

- Province of Cosenza : Cavallerizzo (Cerzeto) , Cervicati , Cerzeto , Mongrassano , Rota Greca , Santa Caterina Albanese , San Giacomo (Cerzeto) San Martino di Finita , Spezzano Albanese

- Province of Crotone : Carfizzi , Pallagorio , San Nicola dell'Alto

- Sicily:

The icons and their meaning

In the context of Byzantine and Slavic culture, the icons are a valuable and culturally important part. The term icon comes from the ancient Greek εἰκών, (eikón), which means "picture" or a picture of a saint painted on wood . The icon is actually the graphic expression of the Christian message, which is why the icons in the Slavic languages are not painted, but "written". Thus one can speak of theological and not of religious art. The big difference between the Byzantine icons and the Catholic paintings lies in the vision of iconography , which in the Byzantine rite requires a profound spiritual preparation, more than a mere technical skill. Before the artist begins to paint, he spends a period of asceticism in order to enter into a dialogue with the divine through spiritual and spiritual purification and thus to be "inspired" for the success of the icon. Through this special spiritual path and its theological content, the icons are considered the work of God, which is expressed through the hands of the icon painter.

Known Arbëresh

- Andrea Alessi (1425–1505), sculptor and architect

- Luca Baffa (1427? –1517), leader and captain of the Albanian mercenaries, naturalized Italian; he was a soldier in the service of Ferdinand I and Ferdinand II.

- Marin Barleti (1450–1513), Catholic cleric, humanist and historian of Albania

- Giovanni de Baffa (1460? –1483), Franciscan (possibly son of Luca Baffa)

- Demetrio Reres (15th century), Albanian general in the service of Alfonso I.

- Gian Girolamo Albani (1504–1591), cardinal of the Catholic Church.

- Giorgio Basta (1540–1607), son of Demetrio, ensign, commander in the Dutch army, governor of Nivelle

- Demetrio Capuzzimati (15th / 16th century), Albanian captain in the service of Charles V; Founder of San Marzano di Giuseppe in Apulia

- Lekë Matrënga (Italian Luca Matranga ; 1567-1619), Orthodox clergyman and author

- Giovanni Francesco Albani (1649-1721); as Pope Clement XI. from 1700 to 1721

- Annibale Albani (1682–1751), cardinal and bishop

- Giorgio Guzzetta (1682–1756), priest of the Greco-Byzantine rite of the Albanian minority in Sicily

- Antonio Brancato (1688–1760), priest of the Greco-Byzantine rite, Italian-Albanian poet

- Felice Samuele Rodotà (1691–1740), first ordaining bishop of the Greco-Byzantine rite for the Arbëresh in Calabria.

- Alessandro Albani (1692–1779), cardinal

- Nicolò Figlia (1693–1769), priest of the Greco-Byzantine rite, Italian-Albanian writer

- Paolo Maria Parrino (1710–1765), papas and man of letters, initiator of the romantic Illyrian-Albanian ideology.

- Pasquale Teodoro Basta (1711–1765), Bishop of Melfi and Rapolla from January 29, 1748 until his death

- Giorgio Stassi (1712–1801), Catholic bishop of Lampsacus and first ordaining bishop of the Byzantine rite per Arbëresh in Sicily.

- Francesco Avati (1717–1800), writer, humanist.

- Giovanni Francesco Albani (1720–1803), cardinal.

- Giulio Variboba (1725–1788), papas , writer and forerunner of modern Albanian poetry.

- Nicolò Chetta (1741–1803), papas, historian, writer.

- Francesco Bugliari (1742–1806), ordaining bishop of the Greco-Byzantine rite for the Arbëresh, titular bishop of Thagaste ).

- Pasquale Baffi (1749–1799), librarian, Hellenist and Italian revolutionary.

- Giuseppe Albani (1750-1834), cardinal

- Angelo Masci (1758–1821), lawyer and scholar.

- Giuseppe Crispi (1781-1859), papas, philologist and historian; ordaining bishop of the Greco-Byzantine rite for the Arbëresh in Sicily.

- Giovanni Emanuele Bidera (1784–1858), poet and dramaturge.

- Pasquale Scura (1791–1868), politician

- Luigi Giura (1795–1864), engineer and architect

- Pietro Matranga (1807–1855), papas, writer and paleographer .

- Vincenzo Torelli (1807–1882), journalist, writer, publisher and impresario .

- Nicolò Camarda (1807–1884), papas, linguist and Hellenist.

- Tommaso Pace (1807–1887), historian, man of letters, Graecist and Italian patriot .

- Domenico Mauro (1812–1873), lawyer, man of letters and Italian patriot .

- Angelo Basile (1813–1848), papas and writer.

- Giuseppe Bugliari (1813–1888), ordaining bishop of the Greco-Byzantine rite for the Arbëresh, titular bishop of Dausara) .

- Girolamo de Rada (Albanian Jeronim de Rada ; 1814–1903), writer, poet and publicist.

- Luigi Petrassi (1817–1842), translator.

- Francesco Antonio Santori (Arbëresh: Françesk Anton Santori or Ndon Santori ; 1819–1894), clergyman, poet and writer; wrote Emira , the first drama in Albanian literature.

- Francesco Crispi (1818–1901), revolutionary, statesman and former Prime Minister of Italy

- Demetrio Camarda (1821–1882), papas, linguist, historian and philologist; the most important researcher of the Albanian language of the 19th century.

- Vincenzo Statigò (1822–1886) writer.

- Vincenzo Dorsa (1823–1855), papas, albanologist , folklorist and philologist.

- Luigi Lauda (1824-1892), abbot, historian and writer.

- Domenico Damis (1824–1904), patriot, general and politician.

- Gabriele Dara il Giovane (Arbëresh: Gavril Dara i Ri ; 1826–1885), poet and politician; one of the first writers of the Albanian national movement .

- Gennaro Placco (1826-1896), patriot and poet.

- Attanasio Dramis (1829–1911), Patriot of the Risorgimentos .

- Agesilao Milano (1830-1856), soldier who committed an attack on the life of the King of the Two Sicilies , Ferdinand II , on December 8, 1856 .

- Giuseppe Angelo Nociti (1832–1899), writer.

- Giuseppe Schirò (Arbëresh: Zef Skiroi ; 1865–1927), poet, linguist and university professor

- Alexander Moissi (arbëresh: Aleksandër Moisiu , Italian: Alessandro Moisi ; 1879–1935), Austrian actor

- Joseph Ardizzone (Italian Giuseppe Ernesto Ardizzone ; 1884-1931), American mafioso

- Tito Schipa (civil Raffaele Attilio Amedeo Schipa ; 1888–1965), tenor and composer

- Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), writer, journalist, politician and Marxist philosopher

- Enrico Cuccia (1907-2000), banker

- Ernesto Sabato (1911–2011), writer, scientist and painter

- Regis Philbin (born 1931), American TV presenter

- Ercole Lupinacci (1933–2016), Bishop of Lungro

- Stefano Rodotà (1933–2017), politician

- Sotìr Ferrara (1937–2017), Bishop of Piana degli Albanesi

- Joseph J. DioGuardi (born 1940), Republican politician and former member of the United States House of Representatives

- Carmine Abate (* 1954), writer

- Francesco Micieli (* 1956), Swiss writer

- Tom Perrotta (* 1961), Italian-American writer and screenwriter

- Kara DioGuardi (* 1970), American musician

- Antonio Candreva (* 1987), football player

- Mateo Musacchio (* 1990), Argentinian-Italian soccer player

See also

literature

- Giovanni Armillotta: The Arberesh. The Christian Albanian emigration to Italy In: L'Osservatore Romano. Vol. 141, No. 139, June 20, 2001 ( frosina.org ), accessed October 25, 2016.

- Antonio Primaldo Coco: Gli albanesi in Terra d'Otranto . In: Japigia (Rivista di archeologia, storia e arte) Ser. NS . tape 10 . Bari 1939, p. 329-341 (Italian, emeroteca.provincia.brindisi.it [PDF]).

- Robert Elsie: Historical Dictionary of Albania. Second Edition, The Scarcrow Press, UK, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8108-6188-6 , p. 17, ( books.google.com ).

- Demetrio de Grazia: Canti popolari albanesi: tradizionali nel mezzogiorno d'Italia , Office Tip. di Fr. Zammit, 1889 ( archive.org , Italian).

- Heidrun Kellner: The Albanian minority in Sicily: an ethno-sociological study of the Siculo-Albanians, presented on the basis of historical and folklore sources as well as personal observation in Piana degli Albanesi. In: Albanian Research. 10, O. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 1972, ISBN 978-3-447-01384-0 .

- Tommaso Morelli: Cenni storici sulla venuta degli albanesi nel Regno delle Due Sicilie. , Volume I, Guttemberg, Naples, 1842, ( books.google.it ), accessed January 14, 2017 (Italian)

- George Nicholas Nasse: The Italo-Albanian Villages of Southern Italy , National Academies, Washington DC, 1964, p. 245, ( books.google.it ). Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- Pasquale Pandolfini: Albania e Puglia: vicende storiche, politiche e religious fra le due sponde dell'Adriatico In: Biblos. 14, No. 28, 2007, pp. 83-92, ( vatrarberesh.it PDF), accessed on November 20, 2016 (Italian)

- Raffaele Patitucci D'Alifera Patitario: Casati Albanesi in Calabria e Sicilia . In: Rivista Storica Calabrese . Volume X-XI (1989-1990), No. 1-4 . Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Calabria, Siena 1990, p. 279-323 (Italian, dimarcomezzojuso.it [PDF]).

- Leonhard Anton Georg Voltmer: Albaner (Arberëshe) dev.eurac.edu (PDF), 2004, accessed on October 25, 2016.

- Laura Giovine: La magia del Pollino . Prometeo, 2006, p. 39 ff . (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- Adam Yamey: From Albania to Sicily . Lulu Press Inc., 2014, ISBN 978-1-291-98068-4 , pp. 146 (English, online version in the Google book search).

- Maria Gabriella Belgiorno de Stefano: Le comunità albanesi in Italia: libertà di lingua e di religione . Perugia 2015 (Italian, unimi.it [PDF; accessed on October 22, 2017]).

Remarks

- ↑ In 1388 Durazzo was attacked by the Ottomans.

- ↑ In 1393 the city of Durazzo was given to the Republic of Venice.

- ↑ In 1272 Charles I conquered the port city of Durazzo (lat. Dyrrachium) and founded the Albanian kingdom (lat. Regnum Albaniae ).

- ↑ Giacomo Matrancha married the noble Laurella Pitruso from Castrogiovanni and had two sons: Andrea and Giovanni, who in addition to the paternal heir, acquired other fiefs and areas, such as Ragalmisari in the Piazza area. This line died out with a third Giacomo in 1513.

- ↑ "This is where Jacobus Matrancha, once Baron von Mantica from Epirus, rests after endless toil, [his] spirit [is] between the stars, and his bones rest here"

- ↑ a b Italian: fouco; here: fireplace = household

- ↑ a b c Casale (plural casali ) is the Italian name for a house or a group of houses in the country.

- ↑ “ … gratitudo liberalitas ac benignitas in illis [scil. regibus] maxime necessarie inesse videntur per has enim a subditis et ser vientibus amantur principes, quo nihil altius nihilque securius ad eorum vite statusque conser vationem habere possunt,… ”(… gratitude, generosity and benevolence seem to be indispensable virtues for a king: in Indeed, thanks to them, the princes are popular with their subjects and cannot expect anything more valuable that gives them security for the defense of their own life and property ...), (Gennaro Maria Monti, p. 161)

- ↑ “ Ferdinandus etc.… Tenentes et possidentes in nostra fidelitate et demanio ac aliter quocumque terram Sancti Angeli de lo Monte et terram Sancti Ioannis Rotundi pertinentiarum provincie Apulee cum castris, fortellitiis, vaxallis, iuribus ac pertinentiis scientia certia nostro presentque motu proprio ac cum nostri consilii deliberatione matura nostreque regie potestatis plenitudine, proque bono Reipublice pacis ac status nostri conservatione tuitioneque prefato illustri Georgio dicto Scandarebech pro se ac suis heredibus, de suo corporeenn legitime natis et nascituris 162 … ”(p )

- ↑ “ … Item perche ad nui per loro misso proprio haveno notificato che vorriano venire in quisto nostro regno pregandoce li volesscmo provedcie de alcuno navilio per possere passare: pertanto da nostra parte li esponente che loro venuta ad nui seravera multo piacere, et da n source carize et honori che figlio deve fare ad matre et patre ad figliolo et non solamente li lassaremo quello ce havemo donato, ma quando bisognio fosse li donaremo de li altri nostri boni - Dat. in civitate capue the xxim mensis februarii Anno Domini Mcccclxviii Rex ferdinandus… ”

- ↑ “ Nos Joannes Dei gratia Rex Aragon. ec. Per litteras Illustrissimi Regis Neapolis Ferdiandi nostri nepotis, erga nos comendati sunt Petrus Emmanuel de Pravata, Zaccaria Croppa, Petrus Cuccia, et Paulus Manisi, nobiles Albani, seu Epitotae strictui contra Turcos et clarissimi et invictissimie Ducis Georgi Castnoia Scanderbegiri et ejusdem consanguinei, aliique nobiles Albanenses, qui in nostrum regnum Sicilie transeuntes cum nonnullis coloniis illic habitare pretendunt. Ideo confisi Nos de eorum Catholica Religione, integritate, eos et omnes nobiles Albanenses, sive Epirotas, liberamus de omnibus collectis, impositionibus, gravitiis, gabellis, et aliis in praedicto nostro Regno impositis et imponendata, eorum vita duredante tantum, prava duredante tantum Cuccia et Manisi, et alios qui eorum nobilitatem ostenderunt. ”

- ↑ “ Illustrissimo Marchese primo nostro Viceré Luogotenente e Capitano Generale come vedrete per una nostra lettera abbiamo accordato di stanziarsi in cotesto reame ad alcuni cavalieri i quali vengono di Corone e di Patrasso e di quelle comarche, fin perché in caso si che tratten possono servire; ordinando che loro assegnate qualche villaggio e terre in Puglia o in Calabria o altre parte di cotesto reame, onde a noi sembra possono vivere e mantenersi; e provvederete che siano per ora finché noi ordineremo altra cosa, liberi di pagamento fiscale, e di qualunque altro dritto, acciò si possano meglio mantenere […] e che dalla nostra tesoreria di cotesto regno loro si dia, e si paghi in ciascun 'anno durante nostro placito settanta ducati di moneta di questo regno. ”

- ↑ a b c “ Carlo V. sensibile al volontario ossequio dé nobili Coronei, che s'erano impegnati a vantaggio della real Corona, fece sottrarre in tempo opportuno molte famiglie dal furore di quelli [ottomani], e trasportarle a sue spese sopra dugento e più bastimenti ai lidi del reame di Napoli con Benedetto, loro Arcivescovo di rito greco. ”

- ↑ “ … et qua civitas ipsa Corone reperitur impraesentiarum in posse Thurcarum gentium, per quod multi Coronenses nostrae Majestati fideles, exules a dicta civitate et privati omnibus bonis quae possidebant, venerunt ad habitandum in presenti regno pro servanda fida et fidelitate ... supplicationibus tanquam justis benigniter inclinati, precipimus et mandamus vobis omnibus supradictis et cuilibet vestrum, quatenus servata forma pro insertorum Capitulorum, immunitates ibi contentas omnibus Coronensibus in praesenti regno commorantiatis ad unguem et inviolabiter exui promittibus etere ... ”

- ↑ Secular clergyman in the Orthodox Church

- ↑ I profughi albanesi, provenienti dall'Epiro, originari del Villaggi epiroti di Piqèras (Santiquaranta) Ljukòva, Klikùrsi, Nivizza, Shen Vasilj, Corfù, trovarono ospitalità nel Regno di Napoli all'Epoca di Carlo III Borbone, che offri loro i terreni ereditati dalla Madre Elisabetta Farnese nel tenimento di Penne- Pianella.

- ↑ Existing Albanian families in Pianiano in 1756: Cola, Micheli, Colitzi (also Collizzi, Colizzi), Lescagni, Lugolitzi (Logorozzi, Logrezzi, Logorizzi), Natali, Mida, Covacci, Pali, Gioni, Halla (Ala), Gioca, di Marco, Cabasci, Brenca, Ghega (Ellega), Carucci, Zanga, Ghini (Gini), Milani, Zadrima (Xadrima), Calmet, Sterbini, Calemesi (Calamesi, Calmesi), Codelli and Remani.

- ↑ Obsolete term for an owner of a café

- ↑ “ I nuovi coloni, senz'arti e senza mestieri, altro non erano se non uomini vagabondi, che passarono nel Regno allettati dal generoso soldo di tre carlini al giorno… ”

Web links

- Website of the Albanian minority in southern Italy

- Jemi - The portal for Arbëreshë

- Link catalog on Arbëreshë at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Gli albanesi in italia (source: Centro Studi Genealogia Arbëreshe), accessed on November 9, 2016

- La storia degli Arbëreshe , official website of the municipality of Vaccarizzo Albanese, accessed on November 9, 2016

- Cognomi di origine albanese (family names of Albanian origin), accessed January 6, 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Legge 15 December 1999, n. 482 Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche. Retrieved October 25, 2016 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c Carmela Perta, Simone Ciccolone, Silvia Canù: Sopravvivenze linguistiche arbëreshe a Villa Badessa . Led Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Drirtto, Milan 2014, ISBN 978-88-7916-666-9 , p. 14 (Italian).

- ^ A b Gaspare La Torre, Elio Rossi: Albania - Italia, Miti - Storia - Arbëreshë . Associazione Amicizia Italia Albania Onlus, Florence, p. 148 (Italian, 1st part , 2nd part ).

- ^ A b Innocenzo Mazziotti: Immigrazioni albanesi in Calabria nel XV secolo e la colonia di San Demetrio Corone (1471-1815) . Il Coscile Editore, Castrovillari 2004, ISBN 88-87482-61-6 , p. 31 (Italian).

- ^ Emanuele Giordano: Dizionario degli Albanesi d'Italia, Vocabolario italiano-arbëresh . Edizioni Paoline, Bari 1963 (Italian).

- ↑ Evoluzione della lingua. In: Arbitalia.it. Retrieved January 15, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Angela Castellano Marchiano: Infiltrazioni calabresi nelle parlate Arbereshe . In: Zjarri . tape X , no. 1-2 . San Demetrio Corone 1978, p. 6-16 (Italian).

- ↑ UNESCO Language Atlas. In: Unesco.org. Retrieved May 31, 2012 .

- ^ Albanian, Arbëreshë: a language of Italy. In: Ethnologue.com. Retrieved May 31, 2012 .

- ^ Leonhard Anton Georg Voltmer, p. 1.

- ↑ Centro di Cultura Popolare - UNLA: Frammenti di vita di un tempo . April 2006, p. 4 (Italian, vatrarberesh.it [PDF]).

- ↑ Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 15.

- ↑ Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 16.

- ^ A b Giornale enciclopedico di Napoli . tape 2 . Orsiniana, 1807, p. 152 (Italian, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Gli arbereshe e la Basilicata (Italian), accessed on November 9, 2016

- ^ Antonio Rubió y Lluch: Diplomatari de l'Orient Català: (1301–1409): col.lecció de documents per a la història de l'expedició catalana a Orient i dels ducats d'Atenes i Neopàtria . Institut d'Estudis Catalans, Barcelona 1947, p. 528 (Catalan, online version in Google Book Search [accessed January 9, 2017]).

- ^ Antonio Rubió y Lluch, p. 587.

- ↑ Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 14

- ↑ a b Konstantin Sathas : ΜΝΗΜΕΙΑ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑΣ. Documents inédits relatifs à l'histoire de la Grèce au moyen age . tape II . Maisonneuve et C., Paris 1880, p. 79 (French, archive.org ).

- ↑ Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 18

- ↑ a b Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 20

- ^ Dionysios A. Zakythinos: Le despotat grec de Morée (1262-1460), Volume 2 . Paris 1953, p. 31 (French).

- ^ A b Ministero dell'Interno: La minoranza linguistica albanese (Arbëresh) . In: Cultura e immagini dei gruppi linguistici di antico insediamento presenti in Italia . Rome 2001, p. 137 (Italian, vatrarberesh.it [PDF; accessed September 20, 2019]).

- ↑ Pasquale Pandolfini, p. 84

- ↑ a b c Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 7

- ↑ a b c d F. Antonio Primaldo Coco: Casali Albanesi nel Tarentino . Scuola Tipografica Italo-Orientale "San Nilo", Grottaferrata 1921, p. 10 (Italian, dimarcomezzojuso.it [PDF]).

- ↑ Johann Georg von Hahn: Journey through the areas of the Drin un Wardar . Imperial and Royal Court and State Printing Office, Vienna 1867, p. 277 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ The Albanian element in Greece . In: Allgemeine Zeitung Munich . tape 7-9 , 1866, pp. 3419 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Johann Georg von Hahn, 1867, p. 278

- ↑ La storia degli Arbëreshe , official website of the municipality of Vaccarizzo Albanese , accessed on November 9, 2016.

- ^ Vincenzo Palizzolo Gravina: Il blasone in Sicilia ossia Raccolta araldica . Visconti & Huber, Palermo 1871, p. 253 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search [accessed December 29, 2016]).

- ↑ D. Filadefos Mugnos : Teatro Genologico Delle Famiglie Nobili, Titolate, Feudatarie & Antiche Nobili, del Fedelissimo Regno di Sicilia, Viventi & Estinte, Libro VI. Palermo 1655, p. 201 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search [accessed December 29, 2016]).

- ↑ Vincenzo Dorsa: Su gli Albanesi: ricerche e pensieri . Tipografia Trani, Naples 1847, p. 72 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search [accessed December 29, 2016]).

- ^ Nicholas C. Pappas: Balkan foreign legions in eighteenth-century Italy: The Reggimento Real Macedone and its successors . Columbia University Press, New York 1981, pp. 36 (English, macedonia.kroraina.com [PDF; accessed on February 13, 2018]).

- ↑ Salvatore Bono: I corsari Barbareschi . Edizion RAI Radiotelevisione Italiana, 1964, p. 136 (Italian).

- ↑ JK Hassiotis: La comunità greca di Napoli et i moti insurrezionali nella penisola Balcanica meridional durante la seconda metà del secolo XVI . In: Balkan Studies . tape 10 , no. 2 , 1969, p. 280 (Italian).

- ↑ JK Hassiotis, p. 281

- ↑ a b c d Laura Giovine: La magia del Pollino. P. 42, accessed November 10, 2016.

- ^ A b Giornale enciclopedico di Napoli, Volume 2, p. 155

- ↑ Margherita Forte and Alessandra Petruzza, collaborators at the information desk of Vena, a parliamentary group of Maida, Le origini della minoranza linguistica albanese (PDF, The origins of the Albanian-speaking minority), 2005, accessed October 25, 2016

- ^ F. Antonio Primaldo Coco, p. 12.

- ↑ a b Vincenzo Dorsa, p. 78

- ↑ Manfredi Palumbo: I comuni meridionali prima e dopo le leggi eversive della Feudalità: feudi, università, comuni, demani . Rovella, Salerno 1910, p. 346 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c Francesco Tajani: Le istorie albanesi . Tipi dei Fratelli Jovane, Palermo 1886, p. 478 (Italian, archive.org , Capo III., 2nd).

- ↑ a b c F. Antonio Primaldo Coco, p. 11

- ↑ Innocenzo Mazziotti, p. 85.

- ^ Giuseppe De Micheli: La comunità arbëreshë di Villa Badessa oggi: Le eredità del passato come risorsa per il futuro . Università degli Studi “G. d'Annunzio ”Chieti - Pescara, 2011, p. 11 (Italian, villabadessa.it [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c Alfredo Frega: Scanderbeg eroe anche in terra di Puglia , Appunti di storia, N. 5, April 2005 (Italian), accessed on November 1, 2016

- ↑ a b Jann Tibbetts: 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time . Alpha Editions, New Delhi 2016, ISBN 978-93-8550566-9 , pp. 575 (English, online version in Google Book Search [accessed November 3, 2016]).

- ^ Domenico De Filippis: I Castriota, signori di Monte Sant'Angelo e di San Giovanni Rotondo, fra mito e letteratura . Centro Grafico Srl, Foggia 1999, p. 9 (Italian, archeologiadigitale.it [PDF; accessed December 10, 2016]).

- ^ Onofrio Buccola, p. 5.

- ↑ Il Casale di Monteparano. (No longer available online.) Associazione Culturale Monteparano.com, archived from the original on November 20, 2016 ; Retrieved November 20, 2016 (Italian).