San Marzano di San Giuseppe

| San Marzano di San Giuseppe | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Country | Italy | |

| region | Apulia | |

| province | Tarent (TA) | |

| Coordinates | 40 ° 27 ′ N , 17 ° 30 ′ E | |

| height | 134 m slm | |

| surface | 19 km² | |

| Residents | 9,087 (Dec 31, 2019) | |

| Population density | 478 inhabitants / km² | |

| Post Code | 74020 | |

| prefix | 099 | |

| ISTAT number | 073025 | |

| Popular name | Sammarzanesi | |

| Patron saint | Saint Joseph of Nazareth (March 19) | |

| Website | San Marzano di San Giuseppe | |

View from San Marzano di San Giuseppe |

||

San Marzano di San Giuseppe (in Arbëresh , IPA : [ar'bəreʃ] : Shën Marcani ; in the regional dialect around Brindisi: Sa'Mmarzanu ) is a southeast Italian municipality with 9087 inhabitants (as of December 31, 2019) in the province of Taranto in Apulia . Together with Casalvecchio di Puglia (in Arbëresh: Kazallveqi ) and Chieuti (in Arbëresh: Qefti ), San Marzano di San Giuseppe is an old Albanian center of the region.

Since San Marzano was almost always owned by Albanian families who wanted to preserve the memory of the ancestors, today San Marzano is the only place among the 14 places inhabited by Albanians (Belvedere (extinct), Carosino , Civitella , Faggiano , Fragagnano , Monteiasi , Montemesola , Monteparano , Roccaforzata , San Crispieri (today a fraction of Faggiano), San Giorgio , San Martino (extinct) and Santa Maria della Camera (now part of Roccaforzata)) in the Albania Tarantina ( Tarentine Albania), the apart from the conservative pre- Ottoman Albanian language (Gluha Arbëreshe), the customs and culture of the country of origin are preserved.

location

San Marzano di San Giuseppe is located on the plateau of a limestone hill of the Murge Tarantine at an altitude of 134 m above sea level. M. The municipality is located between the neighboring towns of Grottaglie , Sava , Fragagnano and Francavilla Fontana about 23 kilometers east of Taranto , 20 kilometers north of the Ionian Sea , 56 kilometers west of Lecce in southern Salento and borders directly on the province of Brindisi .

Seismic activity

According to the Italian classification of seismic activity , San Marzano di San Giuseppe was assigned to zone 4 (on a scale from 1 to 4).

The origin of the name

There is no clear explanation of the origin of the name. On the one hand, it is claimed that the first part of the place name San comes from the Greek and means farmer. It was used for Casali to indicate the craft of the person who lived there. On the other hand, San indicate the Christianization of the first Roman center of a pagan deity Martiis ( Mars ).

Recent studies claim that the name Marzano derives from the Roman " gens " (family group) Marcia , who settled in this area during the Roman Empire and had praedia (possessions) near the Masseria Casa Rossa . Another assumption is that (San) Marzano von Marcus comes from the Marcia family, which is also attested in Terra d'Otranto by other place names and grave inscriptions. Another theory is that Marzano refers to a Roman statio dedicated to a pagan deity Martiis , i.e. Mars.

In the Middle Ages , the toponym castrum Sancti Marzani or Sanctus Marzanus appears, which points to the original name Martianum and not Marcianum . In addition, all documents of the Curia of Taranto related to San Marzano refer to the inscription “casalis Sancti Martialis”.

After the unification of Italy , the mayors of the municipalities of the Kingdom of Italy with the same name were called by royal decree to characterize them with a suffix that identified themselves with the life of the population. On September 7, 1866, the mayor of San Marzano, Francesco Paolo Cavallo, decreed that the medieval place name Sanctus Marzanus should henceforth be called San Marzano di San Giuseppe due to the veneration of Saint Joseph of Nazareth, in order to separate him from San Marzano sul Sarno and San Marzano Oliveto to distinguish.

history

From the Neolithic to ancient times

The territory around San Marzano was already inhabited in the Neolithic Age (5th millennium BC), which is confirmed by numerous finds. There are three specific areas where the earliest forms of human presence are recorded: in the Contrade La Grotte and Neviera and around the Masseria Casa Rossa . In the first contrada, along a Y-shaped ravine-like incision (Gravina), traces of a Neolithic cave settlement were found, which, combined to form a cave complex, can be found around the nearby church, today's rock sanctuary Madonna delle Grazie. Prehistoric stone material such as fragments of volcanic rock glass ( obsidian ) and numerous flint blades have been found there, while grottos dug in the walls of the Gravina, which were used as graves and date from the late Bronze Age (1300–800 BC). These graves were reused as underground dwellings in the early Middle Ages (500 to 1050 AD).

In Contrada Neviera (near the rock sanctuary) remains of a massive wall have been discovered that could have been the borderline between the Greek (Chora Tarantina) and the indigenous ( Messapic ) area of Oria .

In 1897 a necropolis with two Greek graves equipped with Attic dishes and a messapic trozzella was found along the Strada provinciale San Marzano-Grottaglie, about two kilometers outside of San Marzano . The furnishings in the graves and the remains of human bones attest to a period around the 5th century BC. Chr.

The existence of huts in the contrada of the Masseria Casa Rossa , where a Neolithic settlement was found in 1990 , is better documented . The area, which is littered with clumps of plasterworks and ceramic fragments of various kinds, must have been heavily frequented.

In Roman times (8th century BC - 7th century AD) the area of San Marzano was on the border of the Messapian Oria and belonged to the property of Taranto. There was a pagus in the area of the Masseria Casa Rossa . Numerous archaeological finds, such as coins and the remains of a country house, perhaps from a patrician, have been found in Contrada Pezza Padula .

Occasional finds of graves from the early Middle Ages (476 AD-1000 AD) with grave attachments from a fibula , a valuable bronze ring from the 5th / 6th centuries. Century AD and some Byzantine coins are kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto .

San Marzano in the Middle Ages

It is known that the area of San Marzano di San Giuseppe was inhabited in the Middle Ages . Due to the constant raids by the Saracens , which lasted from the 8th century to around the year 1000, the residents withdrew to the caves scattered in the vicinity and to the neighboring communities in the hinterland, where they could live more safely.

There is almost no information about the feudal succession of San Marzano in the centuries before the arrival of the Albanians. The oldest document mentioning this area is from 1196 when the ancient Castrum Carrellum (fortified structure) was associated with the adjacent area of Caprarica . Another document is a deed of donation from 1281 by Andrea, soldier and owner of the fortified structure Castrum Carrellum , to the clergy of Taranto. In 1304 Egidio de Fallosa, owner of the Tenimentum Sancti Marzani ( Sancti Marzani Estate), was asked by the Angevin chancellery to pay tithes to the clergy of Oria.

In 1329 Giovanni Nicola De Temblajo was enfeoffed with the Casale . A document from the archives of Naples from 1378 reports that the feudal lord of San Marzano was Count Guglielmo de Vicecomite, who owned other properties in the Casali of Lizzano , San Paolo, Mandurino and Sant'Erasmo.

Later, when the Casale belonged to the Principality of Taranto , it was derelict and lay on the borders of the Principality. Prince Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo gave it to Ruggero Taurisano as a fief so that he could repopulate it. When his daughter Delizia (also: Adelizia) married Roberto from Monterone and brought the Casale into the marriage as a dowry, it was deserted. Roberto tried to repopulate it and brought it to new life. On January 30, 1461, Delizia gave the Casale San Marzano with royal consent to the son Raffaele, who was followed by the son Roberto, who tried to revive the Casales. In the second half of the 15th century Roberto was involved in the revolt of the local barons (1459-1462) against the King of Naples , Ferdinand I , and was charged with treason. After the death of Ferdinand's wife and heiress of the principality, Giovanna d'Aragona , the Casale together with the Principality of Taranto was given to the Kingdom of Naples in 1465 and partly in small fiefs to established families with Aragonese trust.

Demetrio Capuzzimati and the Albanian Settlement (1530)

The late 15th and early 16th century were many destroyed Casali , which in Albania Tarantina (located in the eastern part of the present province of Taranto) from the Albanian soldiers Georg Kastrioti Skanderbeg during the uprising of the local barons (1459-1462) self-destructs had been rebuilt and settled by Albanians.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the fiefdom of San Marzano belonged to Stefano di Mayra of Nardò , lord of the Casales von Sava , who sold the uninhabited fiefdom in 1504 to Francesco Antoglietta, 8th Baron of Fraganano. It is historically proven that as early as 1508 some Corfiot and Epirotic families from the nearby village of Fragagnano had settled in the sloping village of San Marzano in San Marzano, because they had got into a quarrel with the local population of Fragagnano. The presence of this first small parish could explain the nature of the first urban fabric of the Casale after 1530.

There is little evidence of the first settlement of San Marzano. Only from an inventory of the assets of the “ Università ” (in southern Italy from 1266 to 1807 the name for a more or less independent administrative unit) of Taranto from 1528 it emerges that San Marzano “per servicio Cesareo” (for royal service) ten salms of straw had to pay.

On April 24, 1530, the King of Naples, Charles IV. , Commissioned the Viceroy of Naples , Philibert de Chalon , to auction the property of the royal domains and the fiefs given to the crown in order to reach the sum of 40,000 gold ducats . In return, with this transaction, Philibert de Chalon delegated Lieutenant Pompeo Colonna , the future Viceroy of Naples , to sell cities, plots of land, places, castles, etc. A series of negotiations were started, including the fief of San Marzano in Terra d'Otranto, which was located between the borders of the cities of Taranto and Oria and for which the loyal "caballero de armadura ligera" (knight of the light cavalry) , Demetrio Capuzzimati (Italian surname, which means 'big shoe' in Albanian) made a purchase request.

On July 27, 1530 the royal fiefdom of San Marzano was sold by the viceroy, Cardinal Pompeo Colonna, to the locator and captain of Albanian origin, Demetrio Capuzzimati, for 700 ducats. With the royal approval of Charles IV, the purchase contract was confirmed on February 5, 1536. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Cappuzzimati lived in San Pietro Vernotico and Squinzano in Salento.

Demetrio Capuzzimati († February 17, 1557 in San Marzano di San Giuseppe), 1st Baron of San Marzano, received wide-ranging powers, authority and tax exemption for ten years on the condition that he would “with locals and people” the deserted area of San Marzano that were not registered anywhere in the Kingdom of Naples ”, settled. On 8 November the same year Capuzzimati acquired by the clergy of the Cathedral of Taranto in annual lease also LehenAm 8 November of that year acquired Capuzzimati by the clergy of the Cathedral of Taranto in leasehold and the "de li Riezzi" (Rizzi) fief, where the medieval Castrum Carrellum, which bordered the medieval San Marzano. For this concession, Capuzzimati was to pay 50 ducats in silver carlini (medieval coin in the Kingdom of Naples) to the Tarentine clergy annually. The current San Marzano arose from the merger of the two fiefdoms.

During the rule of the Capuzzimati, the area was populated by numerous Epirotian families who, in addition to their native language, customs and traditions, also brought their Eastern beliefs to their new homeland. While the families helped rebuild the casale and clear the land, Demetrio Capuyyimati immediately began building the feudal palace on the borderline of the two fiefs. The border was exactly between the door leaves of the ancient entrance gate. On one side there was a small group of houses behind today's streets Via Cisterne, Via Trozzola and perhaps also part of the streets Via Vignale and Via Garibaldi. On the other side, the main part of the historic center was between the current Via Addolorata and Via Casalini streets, with access to Palazzo Capuzzimati from the right and left. The two inhabited districts were separated by the park of Baron Capuzzimati, olive and grape groves that reached to the church square of today's mother church. These groves still existed after the Italian unification.

After the death of Demetrius in February 1557, his eldest son Caesare inherited the fief. His successor was his son Demetrio junior in 1595.

A report from 1630 shows that “the houses are around the baron palace, that especially the houses in the Rizzi estate are well distributed and most of them have a flat roof. In addition, the place would be easy to visit both in summer and in winter. ”In the same year the Regia Camera della Sommaria (royal administrative, legal and advisory body) expropriated the fief of the indebted Demetrio and auctioned it in 1639 for 20,000 ducats. Francesco Lopez y Royo from Spain became the new owner.

According to the report of the Tavolario Scipione Paterno of July 8, 1633, the Casale San Marzano bordered in the east on the land of Francavilla, in the west on the Casale Fragagnano and in the north on San Giorgio.

The Margraviate of San Marzano

On April 19, 1645 Francesco Lopez y Royo and his descendants were born by the Spanish King of Naples, Philip III. , honored with the title of margrave . When Francesco died on June 30, 1657, the fief was inherited by his son Diego, who was followed in 1672 by his first-born son Francesco. Since he left no heirs, the margraviate passed to his brother Giuseppe, who was married to Elena Branai (Granai) Castriota, descendant of the direct line of Vrana Konti (confidante and commander of Georg Kastrioti Skanderbeg ). Since the couple had no children, the royal court tried to confiscate the fiefdom after Giuseppe's death in 1699. Elena resisted and offered a transaction of 5000 ducats, which the Regia Camera della Sommaria accepted on July 7, 1700.

When Elena died in 1709, according to her testamentary wishes, the fief went to the great-nephew Giorgio Branai (Granai) Castriota (* 25 nov 1708). When he died in 1726 without an heir, the fief went to Giovanna Branai (Granai) Castriota, a paternal aunt, who gave it to her daughter Elena Sparano in 1744. Elena's husband was Vincenzo Ugone Galluccio (also Gallucci or Galluzzi) from Galatina , Duke of Torah .

A document dated August 17, 1745 shows that the fief was assigned to Elena's eldest son, Francesco Galluccio, who kept the maternal inheritance until his death in 1753. He left no children behind, so his sister Caterina followed him in the line of succession, who refused the fiefdom to become nun "Maria Gaetana" in the monastery of Croce di Lucca in Naples. San Marzano went to the brother Paolo († 8 ottobre 1753), who had it assigned to his underage sister Giovanna. Her father and tutor Vincenzo Ugone wrote to the Regia Camera della Sommaria for her to be entered on the feudal list of San Marzano. In 1755 the fiefdom went to the Baron von Maglie , Giuseppe Pasquale Capece Castriota (1708–1785), who paid the Galluccio family 11,000 ducats for it. He was followed in 1785 by his grandson Nicola and after his death in 1791 by his sister Francesca Maria Capece Castriota, Duchess of Taurisano . The Marquis Filippo Bonelli of Trani turned against the appointment of Francesca Maria as Marchesa of San Marzano to the Sacro Regio Consiglio (judicial body with collegial composition of the Kingdom of Naples) and demanded the part of the feudal estate of the hereditary line of Branai (Granai) Castriota . Bonelli's claims could only be taken over by his heirs after 15 years. On April 14, 1806, the son Pasquale was given the title of Marquis of San Marzano, which his son Pasquale and then his grandson Raffaele, the last Marquis of San Marzano, bore.

In 1929 Raffaele Bonelli sold the Palazzo Marchesale and the holdings of the fiefdom to Angelo Casalini from Francavilla Fontana , whose heirs still own the palazzo today.

Population development

A few decades after the Albanian settlement one reads in a small atlas manuscript that there were 74 “ Fuochi ” (approx. 370 people) in San Marzano in 1575 .

In one of the first documents of the Albanian Casale from 1581 concerning a transaction agreement between the Baron Caesare Capuzzimati and the citizens of San Marzano, one reads the surnames of the families that were settled in the area and some of them still live there today or their names have been changed are. These are: Todarus (today Todaro), Preite (Prete), Joannes Caloiarus (Chiloiro), Andreas Araniti, Antonius Sassus, Lazzarus Lascha (Lasca, Via Lasca), Stasius Musciachius, Petrus Talò, Mattheus Papari (Papari), Duca Barci ( contrada Barsci), Dima Raddi (grotta Raddi), Guido Borsci, Martinus Rocara, Giorgius Riddi, Antonius Magrisi (grotta Magrisi), Coste (Di Coste), Capuzzimadi (Capuzzimati), Rasi, Borgia (Borgia) u. a. more.

From the assessment of San Marzano by the Tavolario Salvatore Pinto on December 3, 1630 it emerges that there were 53 Fuochi (about 250 people) in the place. According to the report of the Tavolario Scipione Paterno of July 8, 1633, 75 families ( Schiavoni and Albanians) lived in San Marzano . A document from 1736 shows that the place numbered 410 people; In 1921 there were around 3,000 inhabitants.

language

The preservation of the Arbëresh distinguishes San Marzano di San Giuseppe from the other places in the Ionian province that were once founded by Arbëresh. By not participating in the cultural and economic changes of Taranto, the ethnic identity with all its rites and folklore was preserved at least until 1622, when the Archbishop of Taranto, Antonio D'Aquino, started the process with the official suppression of the Greco-Byzantine rite initiated the Latinization of religion, which accelerated the disappearance of Balkan traditions and customs.

Even today, the older people speak their original language Albanian (Arbërisht, Arbërishtja or Gluha Arbereshe), a sub- dialect of Tosk (Toskë), which is spoken in southern Albania where the mass Diaspora originated. At present, however, one can observe a gradual loss of the Arbëresh's linguistic legacy, as only half of the population use the language to a limited extent in private.

The language becomes visible in the street signs and names, some of which still exist in San Marzano di San Giuseppe. An old street sign in three languages (Italian, Arbëresch, English) near the entrance to the town welcomes the visitor.

religion

In addition to their Albanian language, customs and traditions, the Albanians also brought their Byzantine Orthodox religion with them to their new homeland from southern Albania .

As soon as they arrived, each family tried to build a house in the Rizzi fief (today in Via Giorgio Castriota). A little below, roughly where the church of San Carlo Borromeo stands today, the church of Saint Paraskeva was built according to Greek custom (“more graeco”) facing east-west with the altar in the east and the entrance in the west. In the Byzantine tradition, the apse is always towards the east, where the sun rises, symbolizing the kingdom of light that represents the Lord God.

With the bull of 1536, Pope Paul III. to the Albanians in Italy full recognition within Catholicism . A report from 1575 to the Holy See in Rome shows that the Archbishop of Taranto, Lelio Brancaccio, described the Albanians of Taranto as "people without faith and without law " and encouraged them during his visit to Albania Tarantina in 1578 he urged the Greco-Byzantine communities to adopt the Latin rite .

On May 4th, 1578, the Greek-Byzantine community of San Marzano received its first pastoral visit from Lelio Brancaccio. He was received by Papas Demetrius Cabascia, who had been ordained by a passing metropolitan in 1560 at the age of twenty . Brancaccio's information shows that Papas Cabascia followed the Eastern liturgy and administered the sacrament according to this ritual, he held the Holy Liturgy on Sundays and holidays, blessed the baptismal water on the eve of the Epiphany , and provided the oil for the unction of the catechumens when it was needed. For several years Papas Cabascia kept the Eucharist for the sick and the Chrisma (consecrated anointing oil) consecrated in “Cœna Domini” ( Mass of the Last Supper ) .

The parishioners were zealous in religious practices, lived in accordance with the ritual of the Fatherland, donated wheat for the Eucharist, oil for the lamp of the Blessed Sacrament , money for wax, and took care of the morality of the holy place. The newlyweds married by exchanging the crowns, not the rings. Everyone (including children and old people) paid attention to the great fasting period , during which the use of meat, dairy products and oil was forbidden until Holy Saturday and no abnormal behavior was ever registered.

Lelio Brancaccio urged the population that it was time to abandon the Greco-Byzantine rite and adopt the Roman-Latin rite. The unanimous answer was that she wanted to continue to live according to the religion of her fathers. The archbishop, convinced that this depended mainly on Papas Demetrius Cabascia, urged the young clergy to attend the seminary of Taranto, where they were received free of charge. Only two clerics appeared from San Marzano (Aremiti Andrea and Zafiro di Alessandro Biscia), who shortly afterwards returned to their hometown without saying goodbye. Brancaccio was very saddened by this incident and wrote to the Baroness of San Marzano on May 11, 1578 to find out the reasons. The answer is unknown. Even if other prelates tried to persuade the population to convert in the following years , the Greco-Byzantine rite lasted for many years.

It was not until 1617 that the Sammarzanesi asked the Archbishop of Taranto, Bonifacio Caetani , to ordain the cleric Donato Caloiro from San Marzano according to the Roman rite, because one dad was not enough to take care of the pastoral care of the community. The fall of the Greco-Byzantine rite and the associated religious rites began in San Marzano and the surrounding Arbëresh communities with the suppression decree of 1622 by Archbishop Antonio d'Aquino.

The lost rites

The transmission of the Arbëresh tradition was entirely oral. The lack of written sources increased the risk of losing much of the oral heritage. Even if the Arbëresh were recognized as an ethnic minority in Italy by Law No. 482 “For the Protection of Historical Linguistic Minorities” of December 15, 1999, it is not enough to preserve the cultural heritage, history, identity, religion, tradition and folklore means protecting and promoting.

The two most important events in the life of San Marzano that reminded of the homeland of Albania were the wedding and the funeral. There is no trace of these religious rites left in the village today.

The wedding

The papas received the wedding couple on the church threshold and accompanied them into the church, where he placed the wedding crowns adorned with colorful ribbons on their heads. The use of the crown was already attested by Tertullian , who symbolized grace in it. This custom was so important in the wedding celebration that, even as the custom waned over the centuries, the name crown continued to suggest the sacrament of marriage.

During Holy Communion , the papas handed the bride and groom a piece of bread, which both of them took turns to eat, and a glass of wine, which both of them took turns to drink. This custom symbolized loyalty and no one else was allowed to drink from the same glass. Then the papas made the bride and groom walk around the altar three times and consecrated the successful union. Finally, the dad threw the glass the couple had drunk from into the baptismal font. As a good omen, the glass had to shatter.

The bride and groom were then left alone in their new home for eight days. On the eighth day, however, they left home to visit their relatives. The bride wore the “dress of the eighth day”.

In every Arbëresh center in Albania Tarantina, as well as first in the rest of the Kingdom of Naples and later in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies , the wedding dress meant for the bride and for those invited not the desire to be beautiful and elegant and to be admired, but to belong a group. It was a clear element of the ethnic status of the person or group itself.

The clothes were sewn themselves and only for the fine work or the embroidery were turned to a professional embroiderer. Every girl dreamed of the wedding and was a master weaver. The trousseau, the dresses and the embroidered or crocheted lace (the most coveted accessory) were the result of long working days and endless winter evenings.

The finest fabrics, such as silk or brocade from Damascus , were often bought at the major fairs , mainly those of Casalnuovo ( Manduria ), Oria and Taranto.

The wedding dress, the dream of all young Arbëresh girls and its long and expensive realization was like a sacred rite. It was made of precious fabric with delicate colors. Pastel colors were preferred and almost never white. There were also accessories especially for the occasion. These were a long veil, the crown and the most beautiful jewelry. The cloak with a train, through which the bride stood out from the wedding procession, when it passed through the streets of the village to the husband's house after the ceremony was over, had a great effect.

The funeral

Another rite that has been lost is burial. The coffin was surrounded by women who wore gala dress for three days (the mourning dress was not put on until the fourth day) and sang mortuary lamentations with open hair while they placed sweets and food on the coffin for the visitors. As a sign of widowhood or widowhood, the survivor darkened the two wedding crowns that had been attached to the headboard of the bed on the wedding day.

Arcipurcium

The Arcipurcium was an important festival . The word generally means festivals, banquets, but was mainly used for carnival . The banquet was celebrated by families of the same tribe during the last three days of Carnival. They ate, drank and sang. The women wore holiday dresses or the “eighth day dress”. Albanian songs, called Valie , were intoned and the Albanian choreographic Vallje dances ( Vallettänze ) were danced until late at night . The themes of the Vallje, songs and serenades were happy, but also painful and nostalgic, sometimes scary. They told of the heroic deeds of Georg Kastrioti and his brave soldiers, of love and longing for the lost homeland, of the diaspora as a result of the Turkish invasion and of the love for their wives.

Finally the elder drank to the common salvation. The festival ended the carnival and initiated the abstinence from meat and dairy products, which the Arbëresh consistently observed during Advent and Lent .

The churches of San Marzano di San Giuseppe

The first church in San Marzano

The first flat-roofed church was dedicated to Saint Paraskeva and was built in the Greek style , but without iconostasis . The walls were painted with oriental icons . The interior was divided into two arches and the main altar was three steps higher than the nave. Above the altar was the tabernacle , where the holy of holies was kept in fermented bread. The altar was covered with three tablecloths and the holy oil was kept in a niche , which was not renewed every year, but only when a Greco-Byzantine bishop came by.

The Church of San Carlo Borromeo

The current church was built at the beginning of the 16th century following the Suppression Decree of 1622 on part of the area where the Church of St. Paraskeva had previously stood and is dedicated to San Carlo Borromeo .

The Chiesa dell'Addolorata

The Chiesa dell'Addolorata was built in 1853 with the bequest of the couple Rosaria Cotugno and Pietro Greco. The church has a simple structure with a single nave and a vault made from local tuff.

The church consists of four side arches supported by eight brick columns. Each arch has a star vault. Opposite the entrance is the brick altar and above it a painting of the burial of Jesus Christ. Above is a choir , the balcony of which faces the interior of the church. There could monks attend the church service, while the ground floor was reserved for women.

The rock sanctuary Madonna delle Grazie

The rock sanctuary Madonna delle Grazie is located three kilometers northwest of the center of San Marzano di San Giuseppe on the Strada provinciale to Grottaglie five meters deep between two ravine-like incisions, called Lama, which at a height of 98.6 m above sea level. M. merge into a larger channel and form a Y. On one side is the crypt on the "Lama" (102.3 m above sea level ), the border to Grottaglie. The church was first mentioned in a document in 1709.

Scientists today agree that the current configuration of the pilgrimage site is the result of extensions and renovations in the 17th century when the Albanian colony that settled in San Marzano cultivated the land to the outer edge of the Rizzi fiefdom, which Upper church built two rock crypts , that of St. George and that of Madonna delle Grazie united and connected them with an internal staircase with the upper church.

The church consists of a nave with an altar made of local stone, above which is a fresco of the Madonna and Child and Saints Joseph of Nazareth (left) and Anthony of Padua (right). To the right of the altar is a statue of the Virgin Mary and Child .

On the church facade , which is surmounted by a bell gable, there are decorative elements of the Albanian school mainly on the pilasters and above the entrance.

Today's Madonna delle Grazie crypt is a large square room with monumental columns , one of which was added for structural reasons. Until recently, the original internal staircase was bricked up and you got to the first room of the rock crypt via the southern external staircase. In this George's crypt there is a small lenticular dome with concentric chiseled circles giving an illusion of depth with a Greek cross in the center.

The northern part of the crypt, where the monolith of the Virgin Enthroned with the Child on her left arm is located, the crypt consists of a single nave and certainly formed the original structure of the second crypt, which was extended to the south where there is the Byzantine frescoes of Saint Barbara from the 13th century and Saint George from a later period.

Around the 17th century the vault was raised with the visible change in the conformation of global spaces. There are no clear sources about this place of pilgrimage.

On the history of the place of worship

Archaeological finds from cave tombs near the southern entrance of the crypt attest to a long human presence in the area since the late Bronze Age . The caves were used as dwellings in the Middle Ages. Some finds of black lacquered ceramic go back to the time of the Magna Graecia .

The origin of this cult site is towards the end of the High Middle Ages when it was a rock settlement along the Lama, the feudal wall between San Marzano and Grottaglie, in the area of the ancient Castrum Carrellum (a military restricted area), which was previously known as Defensa di San Giorgio that was inhabited by locals. It is believed that this community was founded by Basilian monks who came from the east during the Byzantine Iconoclasm (726) to find shelter in the gorges of the Ionian region . Within this small rock community there were several crypts, including those of Saint George and that of the Madonna delle Grazie. This rural center, with its cave dwellings, had a prosperous life until at least the year 1300 when it fell into disrepair, depopulated and forgotten.

A document from 1478 shows that the Lama was named San Giorgio . According to tradition, the place was discovered by the Albanian settlers during the reclamation of the land, which resulted in a dispute between the inhabitants of San Marzano and those of Grottaglie, which was in favor of the Sanmarzanesi, as the eyes of the Virgin of the Sanctuary oriented towards San Marzano.

In the post-Tridentine period (after 1563) the pilgrimage site was dedicated to the Madonna delle Grazie. In the report of the Archbishop of Taranto, Lelio Brancaccio, from 1578 the pilgrimage site is not mentioned.

The first description of the San Marzano pilgrimage site is a report dated June 1897 by the director of the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto , E. Caruso, to the director of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples :

“I had a second and important discovery from a large number of old caves in a former snow pit. Arkosolia and rectangular sanctuaries can be seen from some that have retained their primitive shape . There are small Christian catacombs and one of these grottos has been converted into a modern church and opened for worship. The vault has been enlarged and supported by several pillars, all of which are now colored white with lime. The vault was chiseled to give a little more height in the catacomb (or old Christian church). Byzantine frescoes are still preserved; one is a Madonna and Child (well preserved), now called Madonna delle Grazie. It is located at the top and center of the altar and is carved from the same rock. An arcosolium was carved out on the back to isolate it from moisture. On either side of the portrait are the following Greek letters: MHP OY [Mother of God] IO XC [Jesus Christ]. The painting has been restored several times to revive the colors, but the primitive painting kept coming to light. A second altar on the right has a fresco on the upper part of the wall, indistinguishable from one another, where I could observe two virgins and a saint.

A second, called the Grotto of the Crucifix , consists of a large room with three niches on the left wall and two large arcosolias supported by a large pillar . The Grotto of the Crucifix is so named because there was once a painting there that is now worn by the times and by the shepherds who sheltered there during the rainy season. Due to the action of rainwater, a petrified layer of stucco appears on the walls . On one side of the wall there are three crosses carved into the boulder, which indicates a path of suffering (but I suspect that these are from more recent times). "

economy

Economically, the area is agriculturally characterized by the cultivation of wine and olives. In 1962, 19 winemakers from San Marzano united and founded the "Cantine San Marzano" winery. In the meantime 1200 winemakers have joined the cooperative.

On September 17, 1956, the Cassa Rurale ( Raiffeisenbank ) was founded by San Marzano di San Giuseppe. Today the Banca di Credito Cooperativo (BCC) has nine branches in the province of Taranto.

From 1840 the liqueur "Elisir San Marzano Borsci" is produced in San Marzano. In the 20th century a distillery was established in Taranto, in Quartiere Paolo VI, which asserted itself in the production of the liqueur and in the 1980s the liqueur was brought to the national market with an advertising campaign.

Infrastructure and traffic

San Marzano di San Giuseppe is a bit off the main streets. The main road connections are:

- Autostrada A14 Bologna -Tarent ("Barriera" Massafra ) to and from Northern Italy .

- SS 7 ter Salentina

- SS 7 Via Appia from Taranto to Lecce .

The next larger train station is in Taranto.

Attractions

-

Parocchia San Carlo Borromeo in Corso Umberto I

- Chiesa dell'Addolorata in Via Addolorata

- Palazzo Capuzzimati (also: Palazzo Marchesale, Palazzo Casalini) with Chiesa San Gennaro in Largo Prete

- Scanderbeg statue in Via Piazza Milite Ignoto

- antique arbëresh houses with typical Albanian chimneys in via Giorgio Castriota

- Santuario Madonna Delle Grazie in a side street of the SP 86 towards Grottaglie

- Trullo of the brigand Cosimo Mazzeo , called Pizzichicchio in Contrada Bosco, Strada comunale San Marzano - Oria, in the direction of Oria

- Masseria Casa Rossa with typical Albanian chimney in Contrada Ficone; on the SP 86 in the direction of Sava , about 2 km from San Marzano di Giuseppe

Regular events

The feast of the patronage of Saint Joseph of Nazareth

The patron feast of Saint Joseph of Nazareth, the protector of families, the poor, orphans and carpenters, is celebrated on March 19 and coincides with Father's Day in Italy . The date falls during a season when the olive trees are pruned. From northern to southern Italy it is common to collect these branches and turn them into a bonfire . The symbolism has ancient origins and represents both purification and the beginning of spring. For many, it offers a happy moment of union and an excellent opportunity to experience the atmosphere of the fire.

In San Marzano di San Giuseppe, the patron saint feast of Saint Joseph of Nazareth can be traced back to ancient roots and is still experienced today by the whole population as a very important event.

The blessing of the bread

The rite of the blessing of the bread is linked to the origin of the cult of Saint Joseph, protector of the needy. The round bread with the initials of the saint (SG, San Giuseppe) or the symbol of the cross is one of the main components of the patronage festival. The believing women prepare the dough two days before the festival, which has to rise all night. At dawn on March 18, the dough is brought to the baker to be baked in his oven. Later in the morning the blessing of the bread of St. Joseph ( Italian Benedizione del pane di San Giuseppe ) is performed. After the blessing of the bread, it is distributed to the poor and tourists. Tradition is that the bread is broken with the hands and eaten after a prayer to the saint. Once a piece of bread was kept and the crumbs were scattered across the country in hopes of warding off bad weather.

The wood bundle procession

The origin of the wood bundle procession ( Italian Processione delle fascine ) goes back to an event at the beginning of the 19th century that is firmly anchored in the collective memory of the Sammarzanesi. Because of the extremely low temperatures and an excessive emergency, the residents decided that year to forego the usual small campfires in the alleys. But during the night of March 18, the place experienced a violent downpour, which caused great damage to the countryside. There are olive trees destroyed, vineyards and crops of various kinds, which was interpreted as a punishment of the saint.

Thereupon the inhabitants of the place decided to offer Saint Joseph a single large campfire on the wide mountain (in Arbëresh: Laerte Mali ), where the Palazzo Capuzzimati is located. The campfire (in Arbëresh: zjarri e mate , big fire) was so big that it could be seen in the neighboring villages and everyone said that the place burned down. Some people knelt before Saint Joseph to show him strong devotion. There are also said to have been many carts with mules , donkeys and horses. Apparently an elderly owner of a horse is said to have decided to kneel down in front of the statue to ask the saint to protect the animals as well.

Since then, the procession of carts and bundles of wood has been the most impressive popular and religious event in San Marzano. It starts in the afternoon around 4 p.m. and is an endless procession that winds its way through the streets of the village for about three kilometers. Men, women and the elderly are involved, each with his own cargo, like a large trunk on his head or on his shoulders or bundles of cut olive branches. Children also take part in the procession with their self-made wagons loaded with olive branches. At the end, the carters come with their fully packed wagons, a portrait of the patron saint and their decorated horses. Between 40 and 50 horses ( Frisians , Polish draft horses , Murgesen and ponies ) take part in the procession. After a horse kneels down in front of the statue and in front of the church and the blessing of the bundles of wood, the procession - Arbëresh in costume are also involved - to a field outside of San Marzano, where the large campfire is being prepared. It lasts for several hours and is now the largest bonfire in Italy. At the end of the evening mass, the pastor blesses the pile of wood in all four directions. Then fireworks are lit and after a few minutes the campfire, which burns all night long and implores the protection of the saint. Music and pizzica shouldn't be missing.

The “Tavolate” of San Giuseppe

The tradition of the “tavolate” (Italian: table party, round table) has its origins in the custom of holding banquets for the poor and strangers on the feast of St. Joseph (March 19). This in memory of the hospitality that the Holy Family received on their flight to Egypt . This custom is cultivated in Apulia in Salento in the provinces of Brindisi , Lecce and Tarento, but also in Abruzzo , Molise and Sicily .

In ancient times, the implementation of the Tavolate in San Marzano was entrusted to the women of the same district. They gathered in a house to prepare thirteen dishes with spiritual dedication and ritual in memory of the Last Supper. The typical ingredients of rural culture, such as olive oil, flour, pepper, fish, legumes and vegetables are still used today. There is neither cheese nor meat because on the one hand they are expensive and on the other hand because the festival falls during Lent. The main course is the bread, which is served with fennel and an orange; lettuce follows; “ Lampascioni ” cooked with oil and pepper ; “ Faven ” with olive oil, pepper and an anchovy in oil; chickpeas and beans prepared in the same way; a whole boiled cauliflower seasoned with oil and pepper; Rice with tomato sauce and a piece of fried baccalà (salted and dried Pacific and Atlantic cod ); Stockfish with tomato sauce, “Massa di San Giuseppe” ( Tagliatelle ) with olive oil, leek and a piece of baccalà; Long, handmade macaroni made with honey and fried breadcrumbs ; “Cartellate” (typical Apulian sweets) flavored with pepper.

The "Mattre"

On the morning of March 19, before the procession of the saint carried on the shoulders of devotees, the “mattre” (tables for the poor), with typical dishes of the local culinary tradition, are prepared in front of the mother church Mass to be blessed by the pastor to be given to the poor and tourists.

The celebration of Madonna delle Grazie

The believers of San Marzano have always been deeply connected to their co-patron saint, the Madonna delle Grazie. The celebrations are preceded by the pious practice of “7 Saturdays” with prayers, pilgrimages and the communion after confession.

Every Saturday some pilgrims from San Marzano gather at 6 p.m. in Piazza San Pio da Pietrelcina to sing and pray to the pilgrimage site. The novena in preparation for the feast of the Madonna delle Grazie starts on June 22nd and ends on June 30th.

![]()

On July 2nd at 5:00 a.m., the faithful make a pilgrimage from the mother church of San Carlo Borromeo to the pilgrimage site of Madonna delle Grazie, which is about 3 km outside of San Marzano. After the service there is a procession around the rock sanctuary.

San Marzano di San Giuseppe as a film location

- Quando la Scuola Cambia , documentary by Vittorio De Seta (1978).

- Il Generale dell'Armata Morta (The General of the Dead Army) Film by Luciano Tovoli (1983) with Marcello Mastroianni (General Ariosto) and Sergio Castellitto (expert); from San Marzano di San Giuseppe, Carmine De Padova (orderly), Salvatore Buccoliero (old man), Roberto Miccoli (shepherd), Vincenza D'Angela (woman) and Cosimo Calabrese (president) took part.

- Il Senso degli Altri , documentary by Marco Bertozzi (2007).

- Cosimo Mazzeo, una Storia Italiana , feature film by Tony Zecca and Mino Chetta (2012).

- Le Ultime Aquile , feature film by Tony Zecca and Mino Chetta (2013).

- Principe Demetrio Capuzzimati , documentary by Tony Zecca and Mino Chetta.

Sons and daughters

- Giuseppe Borsci, creator of the famous San Marzano Borsci liqueur since 1840 .

- Cosimo Mazzeo (1837–1864), called Pizzichicchio , Italian brigand who is said to have been one of the most famous in Apulia; he was sentenced to death.

- Carmine Garibaldi (1885–1951), actor; he took part in a total of seven films and died after falling in Rome while making the film Quo Vadis? .

- Oreste Del Prete (1876–1955), math and physics teacher.

- Carmine De Padova (1928–1999), teacher, historian and Italian-Albanian writer.

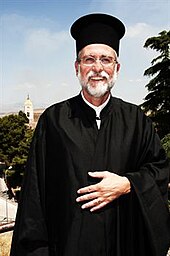

- Angelo Massafra (1949-), Franciscan ; moves to Albania in 1993; 1998 Metropolitan of Shkodra ; since May 4th 2012 Chairman of the Roman Catholic Church in Albania .

- Giuseppe Gallo, teacher, translator and interpreter; as a book author he has written several texts in Arbëresh and is the author of the only dictionary of the Albanian language of San Marzano di San Giuseppe "L'Arbëreshë di San Marzano".

- Tony Zecca and Mino Chetta, amateur directors.

People related to the place

- Demetrio Capuzzimati († February 17, 1557 in San Marzano di San Giuseppe), captain of Albanian origin, son of a soldier who fought alongside Skanderbeg against an uprising of the local barons (1459-1462) incited by the French Anjou .

photos

The trulli of San Marzano di San Giuseppe

See also

literature

- Giovanni Belluscio, Monica Genesin: La varietà arbëreshe di San Marzano di San Giuseppe . In: L'Idomeneo. n.19 . Università del Salento, 2015, ISSN 2038-0313 , p. 221–243 (Italian, unisalento.it [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- Vincenzo Bruno, Antonio Trupo: La chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta , III edizione . Rubinetto print, Soveria Mannelli (Catanzaro) 2011 (Italian).

- F. Antonio Primaldo Coco: Casali Albanesi nel Tarentino . Scuola Tipografica Italo-Orientale "S. Nilo", Grottaferrata 1921 (Italian, dimarcomezzojuso.it [PDF; accessed on May 17, 2017]).

- F. Antonio Primaldo Coco: Gli albanesi in Terra d'Otranto . In: Japigia, Rivista di archeologia, storia e arte, Ser. NS, vol. 10 . Bari 1939, p. 338 (Italian, brindisi.it [PDF; accessed on May 17, 2017]).

- Pietro Dalena: Insediamenti albanesi nel territorio di Taranto (Secc. 15-16): realtà storica e mito storiografico . In: Miscellanea di Studi Storici-Università della Calabria . Centro editoriale librario Università della Calabria, Vol. II, 1989, pp. 36-104 (Italian, vatrarberesh.it [PDF; accessed May 17, 2017]).

- Natascia De Padova: L'arbëreshë di San Marzano di San Giuseppe (Taranto) - Aspetti sociolinguistici . Narcissus.com, 2014, ISBN 978-6-05033051-9 (Italian, limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- Vittorio Farella: Il santuario Madonna delle Grazie presso San Marzano (Ta) ei recenti lavori di restauro . Taranto 1978 (Italian).

- José M. Floristán, Sociedad: Economía y religón en las comunidades griega y albanesa de Nápoles y Sicilia: nuevos documentos inéditos . In: Erytheia, Revista de Estudio Bizantinos y Neogriegos . Asociación Cultural Hispano-Helénica, Madrid 2016, p. 127-204 (Spanish).

- Josephine Fritiofsson: Shën Marxan: San Marzano di San Giuseppe - uno studio sulla lingua e la cultura arbëreshë . Università di Lund, 2013 (Italian, lup.lub.lu.se [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- Dott. Marisa Margherita: Il caso di San Marzano di San Giuseppe, comunità arbëresh fra identità e storia . Sportello linguistico San Marzano di San Giuseppe (Italian, docplayer.it [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- Dott. Marisa Margherita: San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Comunità Arbëresh . Sportello linguistico San Marzano di San Giuseppe (482/99) - (Italian, vatrarberesh.it [PDF; accessed on May 17, 2017]).

- Giuseppe Miccoli: Roccaforzata nell'Albania tarantina. Studi e Ricerche, Arti grafiche Angelini e Pace . Locorotondo 1964 (Italian).

- Francesco Occhinegro: San Marzano in Terra d'Otranto ei suoi demani, vol. 2 . Tipografia Figli Martucci, Taranto 1899 (Italian).

- Mario Mattarelli Pagano: Raccolta di notizie patrie dell'antica città di Oria nella Messapia, a cura di Travaglini . Oria 1976 (Italian).

- Emilio Piccione: L'Albania Salentina. San Marzano di San Giuseppe . Il Salentino Editore Srl, Melendugno 2012, ISBN 978-88-96446-08-9 (Italian, issuu.com [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- Vincenza Musardo Talò: San Carlo Borromeo: la santita nel sociale . Tiemme Industria Grafica, Manduria 2010 (Italian, limited preview in Google book search).

- Vincenza Musardo Talò: San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia . Edizioni del Grifo, Lecce 1997 (Italian).

Web links

- Pro Loco San Marzano di San Giuseppe for tourism and cultural promotion. Retrieved February 27, 2017 (Italian).

- Pro Loco Marciana. Retrieved March 22, 2017 (Italian).

- Rrënjët-te-tona-Grupë-Arbereshë-Shën-Marcani (Our roots - Group Arbëresh San Marzano). Retrieved March 22, 2017 (Italian).

Remarks

- ↑ (plural of Casale) is the Italian name for a house or a group of houses in the country.

- ↑ plural of contrada; Italian term for a geographical area

- ↑ several rural buildings for agricultural operations; typical in southern Italy

- ↑ Salma was a measure of weight and was equal to 161.29 kilograms.

- ↑ "possit rehabitare de hominibus et incolis ibidem habitare volentibus de exteris lamen et non regnicolis hec numeratis in ulla numeratione"

- ↑ " ... sono generalmente case matte cover a tetti, sono sì ben poste con buon ordine" e ci si può muovere per il paese attraverso "piane et ample strade nice e d'estate e d'inverno. "

- ↑ Technicians (engineers and architects) who were instructed in the Kingdom of Naples to draw up precise maps of the area with road signs, buildings and their owners.

- ^ Giuseppe Pasquale Capece Kastrioti (1708–1785) married Francesca Paladini in 1742. Her son Nicola Senior (1743–1772) married Maria Vittoria della Valle di Aversa in 1768. The couple had three children: Francesca (born October 22, 1769 + November 18, 1848), Geronima (1771-1846) and Nicola junior (1772-1791), who was born after the death of his father.

- ^ Italian for fire; family households are meant here

- ↑ Secular clergyman in the Orthodox Church

- ↑ [Greek], in the old church term for the baptismal applicants. With the replacement of adult baptism by infant baptism, the catechumenate disappeared .

-

↑ Una seconda ed anche importante scoperta ebbi a farla nel predio Neviera di alcune antiche grotto in grande quantità, che conservando alcune la loro forma primitiva, vi si scorgono degli arcosolii e saccelli riquadri. Esse sono piccole catacombe cristiane ed una di tali grotte è stata trasformata in una chiesa moderna aperta al culto. Ha la volta ingrandita e sostenuta da più pilastri ora tutti imbiancati di calce. La volta è stata tagliata per ottenere una certa altezza in detta catacomba (o antica chiesa cristiana), vi si conservano ancora delle pitture a fresco bizantine; una è la Madonna col Bambino (ben conservata) ora denominata madonna delle Grazie. Essa è nell'alto e nel centro dell'altare ricavato dalla medesima roccia tagliando un arcosolio dalla parte posteriore per isolarlo dalla umidità. Ai due lati dell'Effigie vi sono le seguenti lettere greche MHP OY IO XC [“Madre di Dio” e “Gesù Cristo”]. Tale pittura è stata più volte restaurata per ravvivare i colori ma la primitiva pittura è semper tornata alla luce. Un secondo altare a destra entrando conserva in alto della parete un affresco non ben distinto, nel quale vi osservai due vergini e un santo.

Una seconda grotta detta del Crocifisso si compone di una grande camera con tre nicchie nella parete sinistra e due grandi arcosoli sostenuti da un pilastrone. Essa è denominata del Crocifisso perchè un tempo eravi un dipinto, ora sciupato dal tempo e dai pastori che ivi si ricoverano durante le piogge; però, alle pareti appare ancora lo strato di stucco pietrificato dall'azione dell'acqua pluviale, ad un lato della parete vi si osservano tre croci incise nel masso dinotando il Calvario (ma credo siano modern)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Statistiche demografiche ISTAT. Monthly population statistics of the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica , as of December 31 of 2019.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Casali Albanesi nel Tarentino, p. 53

- ^ Seismic Classification of San Marzano di San Giuseppe , accessed on February 27, 2017

- ↑ Ordinanza PCM n.3274 of 03/20/2003

- ^ General Seismic Classification for Italy , accessed February 27

- ↑ a b c d San Marzano di San Giuseppe (TA) Shen Marcani. arbitalia.it, accessed March 8, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 37

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 35

- ↑ a b San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 39

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 47

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 49

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 50

- ^ Cenni storici. (PDF) Sanmarzano-ta.gov.it, p. 3 , accessed on July 18, 2018 (Italian).

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 51

- ↑ San Marzano di San Gisueppe. Salento.com, accessed May 2, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d e Casali Albanesi nel Tarentino, p. 52

- ↑ a b c d Cenni storici, p. 5

- ↑ Pietro Dalena, p. 60

- ↑ Vittorio Farella, pp. 5-6

- ↑ Mario Mattarelli Pagano, pp. 142-144

- ↑ Giuseppe Miccoli, p. 135

- ^ Casali Albanesi nel Tarentino . In: Roma e l'oriente . Italo-Orientale, Roma 1912, p. 103 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Francesco Occhinegro, pp. 4-19

- ↑ Serena Morelli: Tra continuità e trasformazioni: su alcuni aspetti del Principato di Taranto alla metà del XV secolo (Between continuity and transformation: on some aspects of the Principality of Taranto in the middle of the 15th century). (PDF) Reti Medioevali Open Archive, accessed on August 22, 2019 (Italian).

- ^ Scipione Ammirato : Della famiglia dell'Antoglietta di Taranto . Georgio Marescotti, Florence 1597, p. 38 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b Marisa Margherita: San Marzano di San Giuseppe, comunità Arbëresh. (PDF) Vatrarberesh.it, p. 5 , accessed on March 12, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Cenni storici, p. 11

- ↑ a b c Cenni storici, p. 12

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 65

- ↑ Francesco Occhinegro, pp. 22-23

- ^ J. Ernesto Martinez Ferrando: Privilegios otorgados por el emperador Carlos V en el reino de Nápoles . Barcelona 1943, p. 364 (Spanish).

- ^ San Marzano di San Giuseppe, anima arbereshe. Salentoacolory.it, accessed March 9, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ José M. Floristán, p. 134

- ↑ Francesco Occhinegro, p. 19th

- ↑ a b Pietro Dalena, p. 60

- ↑ Gino Giovanni Chirizzi: Albanesi e Corfioti immigrati a Lecce nei secoli XV-XVII. (PDF) Vatrarberesh.it, p. 3 , accessed on August 24, 2019 (Italian).

- ^ Cenni storici su San Marzano. Prolocomarciana.it, accessed March 10, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c Cenni storici, p. 7

- ↑ a b Cenni storici, p. 13

- ↑ Gallucio family. Nobili-napoletani.it, accessed March 10, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Galluccio o Gallucci. Genmarenostrum.com, accessed January 22, 2019 (Italian).

- ^ Cosimo Giannuzzi, Vincenzo D'Aurelio: La Figura di Francesca Capece e l'Origine dell'Istruzione Pubblica a Maglie . Maglie 2009, p. 9 (Italian).

- ↑ Lopez. Giovannipanzera.it, accessed January 22, 2019 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Cenni storici, p. 8

- ↑ a b c d e Cenni storici, p. 6

- ↑ San Marzano di San Giuseppe - Un'isola culturale in Tera di Puglia, p. 70

- ↑ Vincenza Musardo Talò, p. 30

- ↑ Bullettino delle sentenze emanate dalla Suprema commissione per le liti fra i già baroni ed i comuni . Angelo Trani, Naples 1810, p. 459 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Bullettino delle sentenze, p. 461

- ↑ a b Casali Albanesi nel Tarentino, p. 54

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Cenni storici sulla comunità Arbëreshë. Prolocomarciana.it, accessed May 3, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Vincenzo Bruno, Antonio Trupo, p. 7

- ^ Giuseppe Maria Viscardi: Tra Europa e "Indie di quaggiù". Chiesa, religosità e cultura popolare nel Mezzogiorno . Storia e Letteratura, Rome 2005, ISBN 88-8498-155-7 , p. 377 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c Vincenza Musardo Talò, p. 27

- ↑ Vincenza Musardo Talò, p. 28

- ↑ Legge 15 December 1999, n. 482 Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche. Retrieved October 25, 2016 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d Bianca D'Amore: L'Albania di Terra d'Otranto. Bpp.it, 1975, accessed May 5, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c C'è un po 'di Albania in Puglia in :. In: Puglia, il magazzino delle eccellenze pugliesi. Issuu.com, March 12, 2012, p. 39 , accessed May 5, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Pietro Dalena, p. 63

- ↑ Chiesa dell 'Addolorata. Prolocomarciana.it, accessed April 23, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d e f Santurarrio Madonna delle Grazie. Prolocomarciana.it, accessed April 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d Cenni storici, p. 17

- ↑ Cenni storici, p. 20

- ↑ a b Santuario Madonna delle Grazie. Comitatofestesanmarzano.it, accessed April 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Historical archive of the National Museum of Naples, scaff. XIV, scomp. A, cart. 1B, Taranto. Ritrovamenti, acquisti ed offer: S. Marzano. Oggetti antichi presso il Sindaco, 1897, fasc. 1.5.

- ^ Cantine San Marzano. Retrieved May 21, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ BCC San Marzano di San Giuseppe. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Borsci. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Festa di San Giuseppe. Sanmarzano-ta.gov.it, accessed May 7, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Suggestiva processione delle fascine. Gireventi.it, accessed March 9, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Cavalli e falò più grande d'Italia a San Marzano di San Giuseppe. (No longer available online.) Oraquadra.com, archived from the original on December 1, 2017 ; Retrieved May 12, 2017 (Italian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Festa Madonna delle Grazie. Prolocomarciana.it, accessed May 18, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Quando la Scuola Cambia. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Il Generale dell'Armata Morta. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Il Senso degli Altri. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Cosimo Mazzeo, una Storia Italiana. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Le Ultime Aquile. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Principe Demetrio Capuzzimati. Retrieved May 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Carmine Garibaldi. Retrieved May 19, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Carmine Garibaldi attore nato alla fine del '800 a San Marzano. Retrieved April 22, 2019 (Italian).

- ↑ Il Professor Oreste del Prete. Retrieved April 22, 2019 (Italian).

- ↑ Carmine De Padova. Retrieved May 19, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Archbishop Angelo Massafra. Retrieved May 19, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Luigi Carducci: Storia del Salento: la terra d'Otranto dalle origini ai primi del Cinquecento: società, religione, economia, cultura . Congedo, Galatina 1993, ISBN 978-88-8086-015-0 , pp. 340 (Italian).