Pio of Pietrelcina

Pio of Pietrelcina , better known as Pater Pio ( Italian Padre Pio ; civil Francesco Forgione ; born May 25, 1887 in Pietrelcina , Province of Benevento , Campania , Kingdom of Italy ; † September 23, 1968 in San Giovanni Rotondo in the Italian province of Foggia ), was Capuchins and religious priests . From 1918 he showed stigmata ; He is also said to have had the gifts of healing , prophecy and the observation of the soul, which was the reason for several partly ecclesiastical, partly medical examinations. In critical publications, the stigmata are attributed to natural causes and Pio's work is sometimes rated very negatively. Pope John Paul II beatified Pio of Pietrelcina in 1999 and canonized in 2002 . A cult developed around Padre Pio during his lifetime; he is considered one of the most popular saints in Italy.

Life

Childhood and entry into the order

Francesco Forgione was the eighth child of Grazio Forgione, a farmer, and Maria Giuseppa di Nunzio. Birgittin became one of his three younger sisters .

At the age of about fourteen he felt called to religious life as a Capuchin . On July 6, 1902, Francesco applied as an aspirant to the Capuchins in San Giovanni. After finishing school he joined the Capuchins of Morcone as a postulant on January 6, 1903, at the age of sixteen, and on January 22 he took the religious name Pio (the Pious) to dress them up .

Religious life and priesthood

After taking temporary vows on January 22, 1904, Brother Pio began studying. After staying in Sant'Elia a Pianisi and San Marco in Lamis , he was sent to Serracapriola in 1907 and made perpetual vows on January 27, 1907. In 1909 he was sent to Morcone and was ordained a deacon on July 18 . On 10 August 1910 he was - a dispensation preferred - in the Cathedral of Benevento for priests ordained and celebrated on August 14, 1910, the first Mass in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Pietrelcina.

After his ordination, Padre Pio, because of his poor health, did not spend the years between 1910 and 1916 in the monastery but, with the permission of the Capuchin Order, in his family's house in Pietrelcina. In 1915 he was drafted into the army, but was allowed to leave it on a year-long convalescence leave. In 1918, he was finally declared unfit for service because of bilateral pneumonia .

In 1916 Padre Pio was sent to the Convent of Our Lady of Grace in San Giovanni Rotondo in the Gargano foothills, which at that time consisted of only seven friars. He stayed there until his death in 1968.

Stigmata

In a letter of March 21, 1912 to his spiritual companion and confessor Father Agostino, Father Pio wrote of his devotion to the mystical body of Christ and the premonition that he, Pio, would one day wear the wounds of Christ himself. Luzzatto points out that Padre Pio used in this letter unrecognized passages from a book by the stigmatized mystic Gemma Galgani . He later denied owning the book quoted.

According to Padre Pio's own statement, visible wounds ( stigmata ) first appeared after his vision on September 20, 1918. The vision occurred after the thanksgiving prayer in the choir . She showed the Lord in the posture of a crucified one who lamented the ingratitude of people, especially those who dedicated themselves to him. This revealed the Lord's suffering and his desire to unite souls with his suffering. He had invited Padre Pio “to share in his troubles and to contemplate them”. Padre Pio was then full of compassion for the sufferings of the Lord; and after being asked what he could do, he heard the voice of Christ uniting him with his suffering. After the vision disappeared, he saw "these signs here" "from which the blood dripped." Padre Pio usually wore fingerless gloves to hide the wounds on his hands.

Alleged use of chemical substances

Critics attributed the wounds to the use of caustic substances. In his book on Padre Pio, the Italian historian Sergio Luzzatto developed a chain of circumstantial evidence that made the natural cause of the wounds appear plausible through the targeted use of phenol (carbolic acid). Pio is said to have tried to obtain this in larger quantities through the cousin of the pharmacist Valentini Vista. The cousin was part of a group of devout women who, according to Luzzatto, went in and out of San Giovanni Rotondo. In a letter he received, Pio names the use of phenol as the disinfection of syringes. He is said to have asked this cousin for a large amount of veratrine , an extremely poisonous mixture of different alkaloids, as well as other drugs. The ingestion of the alkaloid mixture results in an insensitivity to wound pain. Padre Pio has not given Vista any medical prescriptions, he notes. Vista took the Bishop of Foggia, Salvatore Bella, in confidence and showed him corresponding letters. Bella sent these documents to the Holy Office in Rome. After Luzzatto's publications caused a sensation in Italy, the Capuchin Order declared in September 2007 that Padre Pio was also responsible for medical services in his convent, and repeated Padre Pio's declaration, made as early as 1921, that the phenol had been used to disinfect syringes .

Development of the cult around Pio

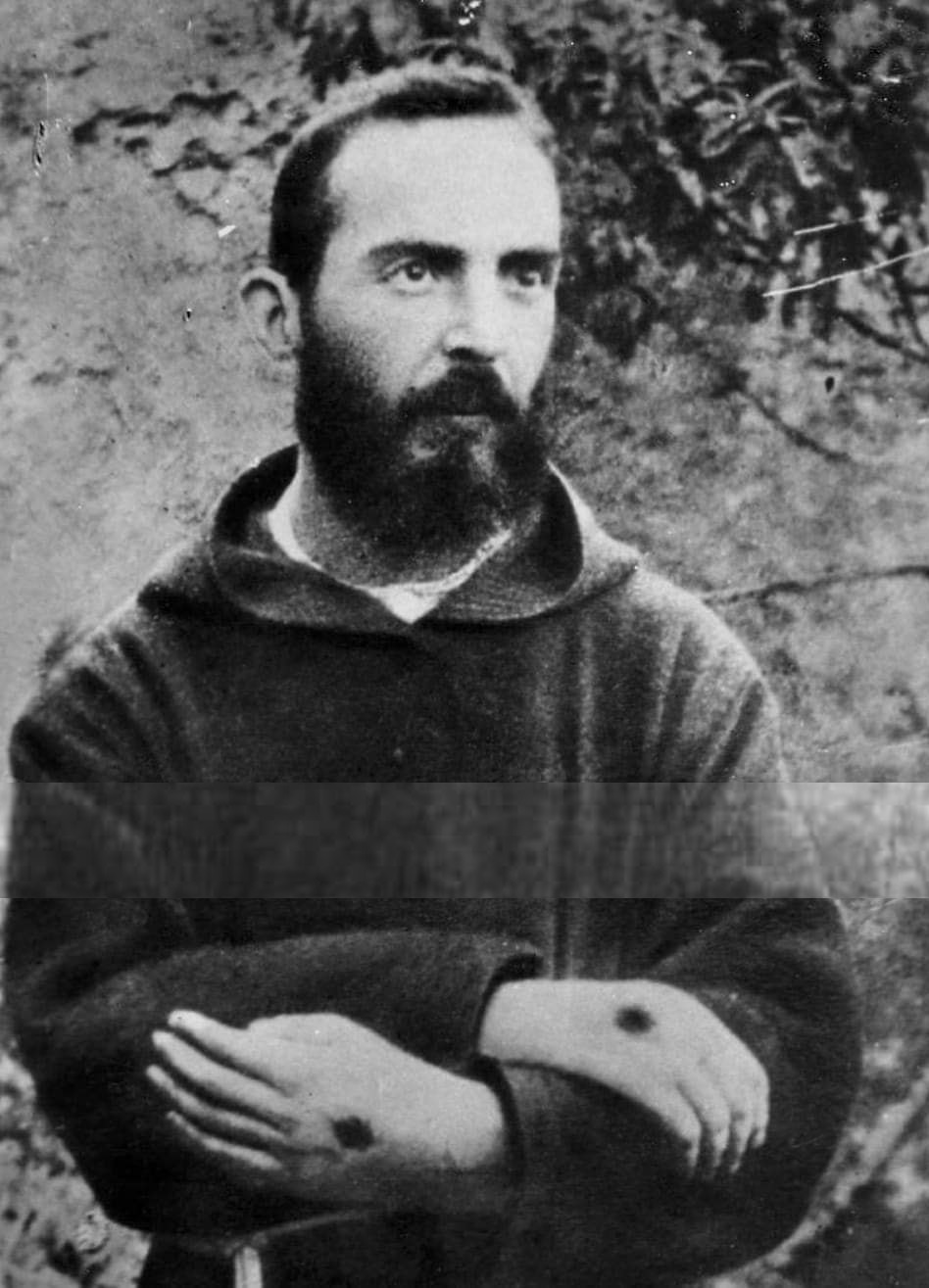

Since 1919 there were signs of a cult around Pio. Also in 1919 reports about Pio appeared in French and Spanish newspapers. The first two biographies of Pio also appeared in Spain. Residents of San Giovanni Rotondo collected blood-soaked handkerchiefs and used them at home as a medicine. A photographer took pictures of Pio that circulated as postcards showing hand stigmata. Objects that Pio had touched (shirts, belts and chairs) were cut up by fanatical followers and taken away from the monastery. During this time, hundreds of people visited Pio every day, according to an Italian newspaper. In addition to the supporters, doubts also reported themselves from the start, including the "Group of Faithful" who called themselves so, who wrote anonymous letters to the Holy Office . They described the supposed miracles as products of the “overheated imagination” of the crowd and named misconduct of the monks.

As early as 1919, the Provincial Minister of the Capuchin Order, Pietro von Ischetella, tried to restrict the cult around Pio. He banned z. B. Lay people to enter the refectory of the monastery. No journalists and photographers were to be allowed into the monastery, and he tried to prevent Pio's objects from being brought out of the monastery.

Restrictions on the exercise of the priestly service

In June 1922 the Secretary of the Holy Office, Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val , planned to severely restrict Pio's powers as a priest. He should be isolated from believers in the best possible way, he should no longer present his stigmata to the public, and his relationship with Father Benedetto should be ended. It was also suggested that Pio be sent to another location. This request, which the Vatican had tackled several times, was ultimately never carried out. Both the fact that Pio enjoyed the support of fascist circles and the fear that violent reactions from the religious population could be triggered were decisive.

In 1923, in a statement published on May 31, the Holy Office announced that there was no evidence of supernatural interference in relation to the phenomena attributed to Padre Pio (non constare de eorundem factorum supernaturalitate) and instructed the faithful to adhere to it . Padre Pio was forbidden to celebrate Holy Mass in public. In 1931 his permission to hear confessions was revoked by the Holy Office, but gradually revoked in 1933, together with permission to celebrate Mass again in public. In 1941, at the request of the Superior General of the Capuchin Order, the Holy Office gave him permission to hear confession in the church in the afternoons; In 1948 he heard the confession of Karol Wojtyłas, later Pope John Paul II.

During the Second Vatican Council , many bishops visited Padre Pio in Giovanni Rotondo. In 1964, Cardinal Ottaviani, as prefect of the Holy Office, announced that Padre Pio “may exercise his office in full freedom”. The attitude of the Vatican to Pio's work was subject to great fluctuations over the decades. The same applies to temporary restrictions on Pios. Ultimately, it was John Paul II who carried out the canonization and thus codified the approval of Pios by the Catholic Church.

Pio as part of clerical fascism

Luzzatto reconstructs Father Pio's open support for the fascist movement from 1920. At that time, “a clerical-fascist mixture developed around Padre Pio ” and the Padre took a positive stance towards Benito Mussolini .

San Giovanni Rotondo, a remote town in a barren landscape, whose illiteracy rate was over 90% in 1920, initially formed Pio's political environment. After the First World War, Italy experienced a political upheaval with civil war-like phenomena, with the socialist and fascist camps facing each other. On the socialist side there were strong anti-religious and anti-clerical currents. On October 14, 1920, a massacre occurred in San Giovanni Rotondo, in which a march of the socialists from the conservative bloc, the Fascio d'Ordine, formed from the (Catholic) Popular Party PPI , the Liberals and the Veterans Organization was attacked. Eleven farmers died, all of them from the socialist camp. A few weeks later, the chairman of the conservative bloc contacted Padre Pio. Later, on the Assumption of Mary (August 15, 1920), the veterans' organizations close to fascism had him bless the flag. Mediated by a young woman whose spiritual leader was Pio, a meeting between him and the fascist politician Giuseppe Caradonna from the Foggia province took place a little later . Pio became the confessor of Caradonna and the members of his militia. After Luzzatto, through contact with Caradonna, a veritable Praetorian Guard was established around Pio, which was supposed to prevent him from being removed from San Giavanni Rotondo by the church. From such beginnings, the clerical-fascist mixture developed over time, in whose creation Padre Pio, according to the reconstruction of Luzzatto, played a part. According to Luzzatto, Pio had clearly sided with the veterans. Conversely, the socialists were often anti-clerical and criticized Pio publicly.

An important follower of Pio was Emanuele Brunatto, one of Pio's first biographers (biography published in 1926 under the pseudonym Giuseppe De Rossi). Brunatto mediated between the supporters of Pio and the leading figures of the fascist movement. The publisher of this book and other biographies on Pio was Giorgio Berlutti , in turn part of the intellectual support for the March on Rome . According to Luzzato, the publication of the biographies was part of an attempt to make Padre Pio known to fascist opinion leaders. Brunatto was possibly from 1931, at the latest from 1935 on behalf of the fascist government and financed by it worked as a spy in France. Pio was connected to his biographer Brunatto in several ways: He acted as managing director of a stock corporation called “Anonima Brevetti Zarlatti”, which sold patents for diesel locomotives. Brunatto was involved in the fact that Padre Pio - despite his vow of poverty - became the owner of this company by donation. The shareholders bought shares in confidence in Pio's stake. After the company went bankrupt, shareholders suffered the corresponding damage. Luzzatto used handwritten notes to prove that Pio was directly involved in the business of the “Anonima Brevetti Zarlatti”. The historian Luzzatto describes Brunatto as a "chronic liar" and cheat, who brought supporters of Padre Pio together with people from the fascist hierarchy and also with leaders from the Vatican.

La Casa sollievo della sofferenza hospital

As early as 1925, Padre Pio in San Giovanni Rotondo converted an old monastery into a clinic with only a few beds, which were intended for people in great need. In 1940, a committee came together to set up a clinic for Father Pio's concerns and to support the project with donations. Construction began in 1947. After Luzzatto, most of the money to finance the hospital came directly from Brunatto, who had made a fortune in black market deals in Nazi-occupied France. In the historiography which Luzzatto describes as "hagiographic", the role of the journalist Barbara Ward in the financing is overemphasized. Ward was the fiancée of Robert Jackson, UNRRA's Vice Secretary . UNRRA was the key institution in the reconstruction of post-war Italy. The UNRRA ultimately went to Lire 250 million to build the hospital. According to Luzzatto, however, Brunatto's amount was twice as large.

Lodovico Montini, top politician of the Democrazia Cristiana , and his brother Giovanni Battista Montini , Vice Secretary of State of the Vatican and later Pope Paul VI, were also involved in the negotiations for financing by the UNRRA . Lodovico Montini became the chief negotiator of a delegation that negotiated with UNRRA on behalf of the State of Italy, while his brother negotiated on behalf of the Vatican. The large sum that went to the hospital is remarkable, because the Italian Red Cross, for example, which is responsible for all of Italy, received only 130 million lire at the time. The hospital was initially to be named after the President of UNRRA, Fiorello LaGuardia , who died in 1947 . Even a corresponding inscription was attached to the building, but it disappeared during the course of completion. Through appropriate interventions by the negotiators and, according to Luzzatto, the “Pater Pio lobby”, the project was ultimately renamed and presented as the work of Pater Pio.

In 1956 the Casa sollievo della sofferenza (“House of Relief of Suffering”) was opened in the city of San Giovanni Rotondo and handed over directly to the Holy See by Padre Pio. In 1967 the hospital was expanded. The clinic, one of only two under the Pope's jurisdiction, now has 1,000 beds.

Death in San Giovanni Rotondo

In 1968 Father Pio's health began to deteriorate, which is why he was last forced to use a wheelchair. He celebrated his last Holy Mass in the early morning hours of September 22, 1968 and died the next day at 2:30 am at the age of 81 with the words "Jesus, Mary", which he repeated again. Over 100,000 people came to the church funeral . After his death, the stigmata disappeared.

Medical and ecclesiastical examinations by Padre Pio

Luigi Romanelli, medical report from 1919

Luigi Romanelli, chief surgeon at the Barletta Public Hospital, believed that Father Pio's wounds were caused by supernatural causes and wrote a report on his views in May 1919. Apparently he had never examined Pio's wounds. Luzzatto writes that Romanelli had twice prayed to Padre Pio for blessings, but they did not materialize. Therefore Romanelli traveled to Padre Pio, who refused him.

Amico Bignami, medical examination from 1919

The pathologist Amico Bignami carried out a medical examination of Padre Pio's wounds in 1919 and came to the conclusion that it was a necrosis of the skin that was prevented from healing with the help of chemicals such as iodine tincture.

Giorgio Festa, medical examinations 1919 and 1920

Festa was a doctor and examined Padre Pio in 1919 and 1920. He was apparently impressed by the fragrance of the stigmata. Festa - like Bignami before - described the side wound as cruciform. All in all, Festa came to a benevolent judgment in his report to the Holy Office of 1925 and attacked Gemelli's critical view of the stigmata Pios, with theological arguments playing the main role.

Agostino Gemelli, psychiatric examination from 1920 and medical-psychiatric examination 1925

A psychiatric examination was carried out by the psychiatrist, Franciscan and priest Agostino Gemelli in 1920. He came to the judgment that Francesco Forgione was a man of “limited knowledge, low psychic energy, monotonous ideas, little will.” Gemelli judged Pio very critically: “It is a case of suggestion, unconsciously planned by Father Benedetto the feeble mind of Padre Pio, which gives the characteristic manifestations of mechanical parroting and imitation typical of the hysterical mind. "

On behalf of the Holy Office, Gemelli re-examined Padre Pio in 1925 and wrote a report on it in April 1926. Gemelli saw the use of a caustic substance as the cause of the wounds. Pio inflicted these wounds on himself. The Jesuit Festa had previously attempted to question Gemelli's statements about stigmata in general. Gemelli responded to this criticism in his report, drawing on his knowledge of self-inflicted wounds in reply. He therefore specified his statements about the nature of Pio's wounds: “Anyone with experience in forensic medicine and beyond with the variety of sores and wounds presented by self-destructive soldiers during the war can have no doubt that these wounds were eroded by caused the use of a corrosive substance. The base of the sore spot and its shape is in every way similar to the sore spots seen on soldiers using chemical agents to prevent them from healing. "

Again Gemelli judged Father Pio's intellectual abilities to be limited: “He [Pio] is the ideal partner with whom the former Provincial Minister, Father Benedetto, can form an incubus-succubus couple… He is a good priest: calm, quiet, humble, more because of the mental deficit rather than from virtue. A poor soul, able to repeat a few stereotypical phrases, a poor, sick man who has learned his lesson from his master, Father Benedetto. ”Gemelli wrote in 1940 and several times later to the Holy Office about what he believed to be incorrect claims Holiness Padre Pios.

Joseph Lemius, vote for the Holy Office from 1920

The French Father Joseph Lemius, who at the time was Procurator General of the Oblates of the Immaculate Virgin Mary , was given a written answer in 1920 to the question of what measures, if any, the Holy Office should take with regard to Father Pio. Lemius judged Padre Pio not on the basis of an investigation, but after looking through files and documents and submitted a so-called vote in which he declared that he could "say nothing with certainty about the origin of the stigmata" and the saint due to the lack of personal inspection The Office recommended sending an Apostolic Visitor, which the Holy Office took up in early 1921. In his vote, Lemius cited four equal hypotheses as to how the wounds found in Padre Pio might have originated:

- self-inflicted from intrinseco (due to an inherent pathological disposition)

- self-inflicted from extrinseco (through suggestion or willful use of artificial means)

- Stigmata of divine origin

- Stigmata of diabolical origin

The latter hypothesis seemed unlikely to Lemius against the background of Father Pio's spirituality; so he rejected them. Lucia Ceci, however, writes that Lemius had come to the conclusion that Pio had brought about the first signs of his stigmata on his hands and feet through the "sheer power of prayer on the wounds of our Lord", but then helped with chemical substances.

Raffaele Rossi, first Apostolic Visitation from 1921

The Bishop of Volterra, Raffaele Rossi , a Carmelite , was formally commissioned on June 11, 1921 by the Holy Office to carry out a canonical investigation into Padre Pio. Rossi began his apostolic visitation on June 14th in San Giovanni Rotondo by questioning witnesses, two diocesan priests and seven friars . After eight days of investigation, he finally prepared a benevolent report, which he sent to the Holy Office dated October 4, 1921, the feast of St. Francis of Assisi . The extensive and detailed report essentially stated the following: Padre Pio, of whom Rossi had a favorable impression, was a good religious and the convent of San Giovanni Rotondo was a good community. Whatever is extraordinary about what happens to Padre Pio cannot be explained, but it certainly does not happen through the intervention of the devil or through deception or fraud. The public exuberance has greatly diminished. During the questioning of the witnesses, which Rossi carried out three times, he asked Father Pio, who was 34 years old at the time, to show him the stigmata and to report on how they came about, which he wrote in the report with “The stigmata are there . We are facing a real fact - it is impossible to deny it ”noted.

In his notes, which were immediately put on paper, and the final report, Rossi describes the shape and appearance of the wounds. The ones in the hands were "very visible" and, in his opinion, were "caused by a bloody exudate". Those in the feet “were disappearing. What could be observed resembled two point-shaped elevations with whiter and softer skin ”. Regarding the page, it says: “On its side the sign appears in the form of a triangular spot the color of red wine and other, smaller spots that at that time no longer form the shape of an inverted cross.” Rossi also made the request to the Holy Office to consult a chronicle about Padre Pio that Padre Benedetto is compiling, or at least to have material collected from him sent to you so that one day one could write about Padre Pio's life.

One of the main factors that made Rossi come to the conclusion during the visitation that the stigmata were of divine origin were the observations that the exudations were bloody . The use of carbolic acid causes a completely different picture and destruction of the tissue through inflammation or suppuration, but the wounds were free of any infection. They did not give off the foul smell of clotted blood, but a very pleasant, penetrating scent, "similar to that of violets", which was also perceptible from a distance.

According to Rossi, the “miracles” attributed to Padre Pio to the Archpriest Giuseppe Prencipe and which caused such a sensation in San Giovanni Rotondo were hardly a true word, for which he expressly regretted Padre Pio: “To think that so many useless words have thrown such an unfavorable light on this poor Capuchin! ”Of these“ miracles ”, for example, were listed: the alleged healing of several hunchbacks, the twisted foot of a clerk, that of a mute girl, and that a bell on a prayer of Father Pios jumped there. Lucia Ceci also writes that Rossi was unable to determine any of the ascribed miracles: “there could be no doubt: not one of the claimed miracles could be substantiated.” (“There could be no doubt: not one of the claimed miracles could be proven. “) When asked about a bilocation, Pio stated that it did not exist,“ as far as I am aware ”.

John XXIII, research and tape recordings, after 1958

John XXIII was extremely skeptical of Padre Pio. At the beginning of his term of office, he learned that Padre Pio's opponents had placed listening devices in his monastery cell and in his confessional and thus recorded his confessional conversations with tapes. On four pages outside of his semi-official diary, John XXIII wrote that he was praying for "PP" (Padre Pio). The content of these private notes was first published by Luzzatto. The tape recordings made it clear that Padre Pio - provided that what was communicated ("si vera sunt quae referentur") was true - had "intimate and indecent relationships with the women from his impenetrable Praetorian Guard around him". John XXIII probably never heard the tapes himself, but assumed that this view was correct. According to Luzzatto, the Vatican did not order this wiretapping. John XXXIII. had avoided contacting Padre Pio in San Giovanno Rotondo years earlier and wrote of his reaction to the scandalous tape recordings: "The reason for my spiritual calm, and that is a priceless privilege and grace, is that I am personally pure feel of this pollution that for forty years has corroded hundreds of thousands of souls that have been fooled and messed up to an unprecedented degree. " In another note, John XXIII wrote that he wanted to take action. Indeed, he ordered another Apostolic Visit.

Carlo Maccari, second Apostolic Visit in 1960

The priest Carlo Maccari was general secretary of the Diocese of Rome and met Pio a total of nine times. Pio was extremely suspicious of Maccari. The latter noted in his diary: "Reticence, narrowness of mind, lies - these are the weapons he uses to evade my questions ... Overall impression: deplorable." Macari demanded that the kiss practiced by Padre Pio be omitted after the confession for the lay sisters . In his report, Maccari noted that Pio had insufficient religious education. He works a lot for a man his age. He was not an ascetic and had numerous connections to the non-monastic world. In general, there is too strong a mixture of the "sacred" and the "all too human". Maccari noted in his report by name which woman said she had been Pio's lover at what time - without making a clear judgment as to whether all these statements were true. Maccari concentrated on assessing the fanaticism of Pio's social environment and describes its manifestation as "religious views that fluctuated between superstition and magic." Maccari described the followers of Pio as an "enormously extensive and dangerous organization". Pio had never advised his followers to moderate himself. Maccari wondered how God could allow "so much deception". Maccari ended his critical report with a list of recommendations on how to deal with Padre Pio. The brothers from Santa Maria delle Grazie were to be gradually transferred, a new abbot was to come from outside the region. Nobody should be allowed to confess to Pio more than once a month. The hospital should get new statutes to separate the tasks of the medical and the spiritually "healing" Capuchins more strictly. Following Maccari's Apostolic Visitation, John XXIII noted in his diary that he saw Padre Pio as a “straw idol” ( idolo di stoppa ).

Old christ

In literature, Padre Pio is referred to several times as the old Christ , "other Christ". Luzzatto ponders the question of whether a good Christian could ever accept the possibility of such an old Christ and what theological difficulties, in his view, are associated with it. The contemporaries of St. Francis had already asked themselves this question, but on the other hand he was not a priest . St. Francis received the stigmata towards the end of his life, while Padre Pio received it as a young man who had carried it for half a century. When Padre Pio celebrated Holy Mass, the stigmata that marked him as a bleeding old Christ were "so evident that they could only be regarded as either sublime or sacrilegious". Such considerations, in turn, help explain the caution, reluctance and suspicion with which Padre Pio was met at the time.

At various points in his book, Luzzatto describes the view of Padre Pio's followers, who saw him as the living Christ. Correspondingly, the Bishop of Volterra Rossi wrote, anything but critical of Padre Pio, that followers of the Capuchin declared him to be the “living Christ” “in pitiful ignorance”.

The Roman Catholic writer Vittorio Messori , on the other hand, sees Padre Pio as a memorial to both the suffering and the risen Christ, in whose wounds one could put one's fingers, as it were, with the doubting Thomas . Messori also states that the stigmata resolved different reactions at the time in question, but sees Father Pio's appearance as a grace from God. Few events in the 20th century contributed so much to the preservation of the faith as "the humble presence of this old Christ , whom God in his goodness granted us".

Attributed Supernatural Phenomena

According to Rose Ann Palmer, the first miracle happened in 1896 when Francesco Forgione was nine years old. He is said to have prayed and cried with a woman whose child was deformed, according to which the child is said to have been healed by throwing it on an altar. This left a lasting impression on Francesco. A miracle is said to have happened for the first time in 1908 after he gave his aunt Daria a sack of chestnuts he had collected himself. Daria later suffered burns on her face in an accident and for relief put the water-soaked sack in which the chestnuts had previously been on her face. After that, the burns completely disappeared without leaving any scars.

In April 1913, the area around Pietrelcina was of a Sternorrhynchaplage compromised, would have meant a loss in the bean crop for local farmers. Francesco is said to have killed all the insects only by praying and blessing the fields, which is why the harvest was particularly rich.

When the grandson of the Freemason and atheist Alberto Del Fante was terminally ill with bone and pulmonary tuberculosis and abscesses of the kidneys, his family asked Padre Pio for his prayer for the boy. Del Fante immediately changed his mind when he found the boy healed almost immediately. He made a pilgrimage to San Giovanni Rotondo, confessed and found his way back to Catholicism. Del Fante then published the work Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, Herald of the Lord , in which he described 36 medically documented miracles of Pio that are said to have happened by 1931.

Padre Pio is said to have predicted the election of young Karol Wojtyła in 1947 as well as the assassination attempt in 1981. An Italian newspaper had already reported in 1959 that Pio had predicted the election of Angelo Roncalli as Pope, a newspaper report that, according to Luzzatto, was completely made up. When listing the miracles, multiple reports also mention that Padre Pio is said to have appeared at the same time in very different places all over the world ( bilocation ).

Adoration and criticism

In the early 1920s, pilgrims increasingly traveled to San Giovanni Rotondo to attend the Holy Masses celebrated by Padre Pio, and chose him as confessor . At times the superiors forbade him to show himself in public. In April 1924, the General Procurator of the Capuchins, Father Melchiorre da Benisa, forbade all Capuchin monasteries to make pilgrimages to Father Pio, to express themselves in writing or to distribute pictures of him in a circular.

On March 20, 1983, fourteen years after the death of Pio of Pietrelcina, the preliminary investigation process for beatification was opened. On June 2, 1997, Padre Pio was promoted to venerable servant of God after establishing the heroic degree of virtue .

Padre Pio was beatified on May 2, 1999 . The St. Peter's Square was to all believers take too small, who wanted to attend the ceremony. The canonization followed on June 16, 2002, about 200,000 pilgrims had traveled to Rome for it. The feast day of Pio of Pietrelcina is September 23rd .

In the summer of 2004, after several years of construction, the new church of San Pio da Pietrelcina by the architect Renzo Piano was consecrated next to the grave of the Father in San Giovanni Rotondo , as the previous church had become too small.

The commercialization of the saint in San Giovanni Rotondo was sometimes sharply criticized: the day before Father Pio's canonization, the Bishop of Como , Alessandro Maggiolini , spoke out against the flourishing business that would have developed in connection with this clergyman. "Jesus Christ drove the traders out of the temple, but I must now say that they have returned," he said in an interview with the Italian daily La Repubblica . When asked about the miracles that were traced back to the intercession of Padre Pios in the two canonization procedures, Maggiolini expressed doubts at the same time.

At the beginning of March 2008, Father Pio's body was exhumed. After an examination in the crypt of the monastery church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, the remains were placed in a glass reliquary for a few months for veneration . The local Archbishop Domenico D'Ambrosio said after the exhumation that when the coffin was opened, the saint's beard was immediately and clearly visible. The upper part of the skull was partially skeletonized, but the chin was perfectly preserved and the rest of the body was in good condition. "If Padre Pio allows me, I would say his hands looked as if they had just been manicured."

Since April 19, 2010, the remains of Padre Pios have been in a reliquary in the lower church of the new pilgrimage basilica. His face is covered by a silicone mask that also recreates the bushy eyebrows and beard. This mask was made from a 1968 photograph of Padre Pio's corpse by the Gems studio in London, usually active in wax museum and ethnological museums.

At the beginning of February of the extraordinary Holy Year of Mercy 2016, at the express request of Pope Francis, the relics of Padre Pio were brought to St.Laurentius Outside the Walls for veneration and from there in a procession to St.Peter's Basilica , where they remained until after Ash Wednesday of the year. Pope Francis himself prayed at the shrine of the saint on February 6, 2016.

On March 17, 2018, Pope Francis went on a pilgrimage to San Giovanni Rotondo. In October 2018, Vatican City issued a 2 euro commemorative coin to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Padre Pio's death.

Movies

In 1968 the Swiss priest Hans Buschor made the documentary Pater Pio, Father of Millions , a film biography about Father Pio with numerous eyewitness accounts and historical film recordings from his life, his last mass and his funeral. Buschor financed the Catholic television station K-TV from the proceeds of the film .

Carlo Carlei filmed the life of Pater Pio for television in 2000 under the title Padre Pio with Sergio Castellitto in the leading role.

literature

- Renzo Allegri: Padre Pio, teacher of the faith . Parvis, Hauteville 2002, ISBN 3-907525-61-2

- Gabriele Amorth : Padre Pio. Life story of a saint . Christiana, Stein am Rhein 2003, ISBN 3-7171-1108-6

- Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011

- Arni Decorte: Padre Pio from Pietrelcina. Memories of a Favorite Witness of Christ . Parvis, Hauteville 2001, ISBN 3-907523-44-X

- Mario Guarino: Beato impostore , Kaos Edizioni, Milan, 1999

- Mario Guarino: Santo impostore , Kaos Edizioni, Milan, 2003, ISBN 88-7953-125-5

- Joseph Hanauer : The stigmatized Padre Pio of Pietrelcina , Bock and Herchenhainer, Bad Honnef 1979, ISBN 3-88347-041-4

- Bernd Harder : Padre Pio and the miracles of faith , Pattloch, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-629-01658-8

- Michael Hesemann : Stigmata. They carry the wounds of Christ , silver cord, Güllesheim 2006, ISBN 3-89845-125-9

- Urte Krass : Controlled loss of face. Padre Pio and photography . In: Journal for the History of Ideas, Volume IV / 2 (2010), pp. 71–96

- Urte Krass: Stigmata and Yellow Press. The miracles of Padre Pio . In: Alexander CT Geppert, Till Kössler (Ed.) Wunder. Poetics and Politics of Amazement in the 20th Century , Suhrkamp, Berlin 2011, pp. 363–394, ISBN 978-3-518-29584-7

- Sergio Luzzatto : Padre Pio: Miracoli e politica nell'Italia del Novecento , Einaudi, 2007 (English translation by Frederika Randall: Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , Verlag Henry Holt, 2011)

- Ingrid Malzahn: Padre Pio von Pietrelcina . Grasmück, Altenstadt 2001, ISBN 3-931723-12-7

- Adi Wassermann: Padre Pio. The stigmatized capuchin . Salvator Mundi, Gaming 1991, ISBN 3-85353-010-9

Web links

- Literature by and about Pio von Pietrelcina in the catalog of the German National Library

- C. Schüle: Cult: In God's Light Report on Padre Pio. Zeit Online, December 22, 2003

Individual evidence

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, pp. 276f.

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, pp. 289ff.

- ↑ Lucinda Vardey, Traveling with the Saints in Italy: Contemporary Pilgrimages on Ancient Paths , Castle Quay Books Canada, 2005, p. 402

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age . P. 19.

- Jump up ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 290

- ↑ Vatican Press Office: Padre Pio von Pietrelcina , June 16, 2002, accessed on November 23, 2018

- ↑ Complete illustration of the photograph by Urte Krass : Controlled loss of face. Padre Pio and photography. In: Zeitschrift für Ideengeschichte, Issue IV / 2, 2010, p. 74, which, according to Krass, elaborates a “staged character” of photography and places it in an art-historical context.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age . P. 19.

- ^ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. Xiii

- ↑ Florian Festl: Miracles from the pharmacy? In: Focus Online . March 4, 2008, accessed October 14, 2018 .

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , pp. 5 and 89 ff.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age . P. 89 ff.

- ↑ Dirk Schümer: The acid saint. Catholic Italy worries: Were the bleeding wounds of the miracle man Padre Pio chemical tricks? in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung No. 249 of October 26, 2007

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age . P. 93 f.

- ↑ Vatican Radio: Italy: End of the Polemic about Padre Pio , October 31, 2007, online at Vatican Radio

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 26.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 24.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 27.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 32.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 39.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 27

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 28.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 41.

- ↑ a b c Lucia Ceci: The Vatican and Mussolini's Italy , Brill, 2016, ISBN 9789004328792 , p. 114

- ^ "The Most Eminent Fathers would like to see such a transfer take place right away." In: Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , p. 105. On the erasure of the memory of P. Pio see. also p. 129.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , p. 167.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , p. 122 ff.

- ↑ Declaration. Acta Apostolicae Sedis, 15 (1923), p. 356, cited above. after Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , p. 121

- ^ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 292

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p 294

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 8.

- ↑ Julius Müller-Meiningen: Padre Pio - Heiliger Scharlatan “But while Italy argues about Padre Pio and the acid, Luzzatto's really important theses are completely different: For example, that the pious father openly supported the rising fascist movement around 1920 and himself at that time 'formed a clerical-fascist mixture around Padre Pio'. ”Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 19, 2010.

- ↑ Urte Krass: Controlled Loss of Face. Padre Pio and photography. In: Zeitschrift für Ideengeschichte, Issue IV / 2 (2010), pp. 71–96 (Paraphrase to p. 74) https://www.zig.de/pdf/ZIG_2_2010_krass.pdf

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 74.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 69.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 68.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 85.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 89.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 85.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 70.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 148

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 149

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 149.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 194.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 192.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 192.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 148.

- ↑ https://de.catholicnewsagency.com/story/das-krankenhaus-auf-dem-hugel-das-irdische-werk-von-pater-pio-3452

- ^ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 293

- ↑ https://de.catholicnewsagency.com/story/das-krankenhaus-auf-dem-hugel-das-irdische-werk-von-pater-pio-3452

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, pp. 205 and 219.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 219 ff.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 221 f.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 226.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 228.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, pp. 225 ff.

- ^ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 293

- ↑ CNA press release: The Hospital on the Hill: Padre Pio's Earthly Work , September 6, 2018, accessed May 5, 2019

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p 294

- ^ Süddeutsche Zeitung : Padre Pio exhumed , March 3, 2008

- ^ Guido Schmid: Stigma / Stigmatization. In: Metzler Lexikon Religion. Present - everyday life - media . JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, vol. 3, p. 384.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 37 f.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 39.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 139.

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011 p. 20, p. 44, 49ff.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 59.

- ↑ "The case is one of suggestion unconsciously planted by Father Benedetto in the weak mind of Padre Pio, producing those characteristic manifestations of psittacism that are intrinsic to the hysteric mind." Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age. P. 59.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, S. 140th

- ^ "Anyone with experience in forensic medicine, and above all in variety of sores and wounds that self-destructive soldiers presented during the war, can have no doubt that these were wounds of erosion caused by the use of a caustic substance. The base of the sore and its shape are in every way similar to the sores observed in soldiers who procured them with chemical means. "In: Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 140.

- ↑ (omission of Luzzatto) Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 141.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 259.

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, pp. 5f.

- ^ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 23

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 20, p. 28, p. 67

- ↑ https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/details_of_first_investigation_into_padre_pios_stigmata_revealed

- Jump up ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 21

- ↑ literally: 'buttons'

- Jump up ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 21

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, pp. 22f.

- ↑ Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 28

- ↑ Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, pp. 25, 52f.

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011 p. 20, p. 100ff., P. 139ff.

- ↑ “[…] not so far as I'm aware.” In: Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , p. 102.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 270.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 270.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 271: "The reason for my spiritual tranquility, and it is a priceless privilige and grace, is that I feel personally pure of this contamination that for fourty years has corroded hundreds of thousands of souls made foolish and deranged to an unheard-of degree. "

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 272.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 273.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 274.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 274.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 275.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 276.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 277.

- ^ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 277.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzato (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, S. 278th

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age . P. 7f.

- ↑ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, pp. 17, 24, 36, 60, 65, 108.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age, p. 108.

- ^ Vittorio Messori in: Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, xxi-xxv

- ↑ Rose Ann Palmer: God Did It: Healing Testimonies Across Time and Religions , iUniverse, 2014, ISBN 9781491733738 , pp. 262f.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto (2011): Padre Pio: Miracles and Politics in a Secular Age , p. 263.

- ^ Fr. Charles Mortimer Carty, Padre Pio: The Stigmatist , Radio Replies Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1963 pp. 55ff.

- ↑ Urte Krass: Controlled Loss of Face. Padre Pio and photography . In: Journal for the History of Ideas , Volume IV / 2 (2010), p. 80

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, pp. 293f.

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation - The secret Vatican files , Ignatius Press, 2011, p 294

- ↑ http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/de/homilies/1999/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_02051999_padre-pio.html

- ↑ a b Spiegel Online: Exhumation: Remains of Padre Pio hardly decomposed , March 3, 2008

- ↑ Orazio La Rocca:Maggiolini: I mercanti sono tornati nel tempio. In: La Repubblica of June 15, 2002 (accessed August 7, 2018); see also Jessie Grimond: Million to see canonization of Padre Pio, the miracle monk who makes fortunes , The Independent . June 16, 2002, p. 17. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- ↑ “As for the miracles, if there are any: we have to see. If someone was lame and now walks around, if he was blind and sees again, well, then there is little left to say. But we have to be careful that these are not inventions, exaggerations, etc. I am afraid there is a possibility that there was a precipitate of emotion here ”. In: Orazio La Rocca : Maggiolini: I mercanti sono tornati nel tempio . In: La Repubblica of June 15, 2002 (accessed September 23, 2018);

- ↑ Translation from body Italy exhumes revered monk's. BBC News , March 3, 2008, accessed June 25, 2011 .

- ↑ According to an article by ORF only since June 2013

- ^ Body of saint Padre Pio exhumed, on display in Italy. Los Angeles Times , April 25, 2008, accessed June 25, 2011 .

- ^ Thousands queue to see corpse of Padre Pio. The Independent , April 25, 2008, accessed June 25, 2011 .

- ↑ Urte Krass: Controlled Loss of Face. Padre Pio and photography . In: Journal for the History of Ideas , Volume IV / 2 (2010), p. 95 f.

- ^ The Washington Post , February 11, 2016: Padre Pio's body leaves the Vatican after drawing thousands of pilgrims

- ↑ Vatican Press Office: Pastoral visit of his holiness Pope Francis to Pietrelcina and to San Giovanni Rotondo, on the 50th anniversary of the saint's death , March 17, 2018, accessed on November 23, 2018

- ↑ Pope Francis Makes Pilgrimage to Honor a Rock-Star Saint , The New York Times , March 17, 2018, accessed November 23, 2018

- ↑ Pope pays tribute to mystic monk said to have wrestled with the Devil , March 17, 2018, accessed November 23, 2018

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pio of Pietrelcina |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Padre pio; Padre Pio; Forgione, Francesco |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian religious priest, capuchin, saint |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 25, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Pietrelcina |

| DATE OF DEATH | 23rd September 1968 |

| Place of death | San Giovanni Rotondo |