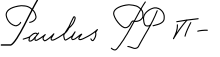

Paul VI

Paul VI (Bourgeois Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini ; born September 26, 1897 in Concesio near Brescia ; † August 6, 1978 in the papal summer residence Castel Gandolfo ) was the 262nd Pope of the Roman Catholic Church and head of the Vatican City State from 1963 to 1978 . Because of his formative role for the course of the Second Vatican Council , his decision-making and the implementation of the decisions, he is considered by some as the actual "Council Pope". Probably none of his predecessors ever enforced such comprehensive church legislation , even if the entire revision of the post-conciliar code of law ( Codex Iuris Canonici ) was only published in 1983.

Pope Francis spoke to Paul VI. Blessed on October 19, 2014 and holy on October 14, 2018 . His feast day in the liturgy is May 29th.

Life

Giovanni Battista (Giambattista) Montini came from the Lombard land nobility. He was the son of Giorgio Montini (1860–1943), a lawyer, newspaper publisher and politician, and Giuditta Montini (1874–1943), née Alghisi. He first studied Catholic theology in Brescia from 1916 to 1920, where he was ordained a priest on May 29, 1920 . Montini then studied in Rome at the Pontifical Diplomatic Academy and at the Pontifical Gregorian University from 1920 to 1923 civil and canon law and philosophy.

Church career

From 1922 Montini worked in the Vatican State Secretariat , where, apart from a brief position at the Warsaw Nunciature , he worked until 1954. His father was from 1919 to 1926 (when all parties were banned by fascism) a member of parliament for the Catholic Italian People's Party (PPI). From 1925 to 1933, Montini was assistant general of the Italian Catholic Students' Union ( Federazione Universitaria Cattolica Italiana ). As such, he had arguments with the fascist regime . From 1937 on, Montini was a substitute a close collaborator of State Secretary Pacelli, later Pius XII. whom he accompanied on his trips abroad. While Montini, after the death of Cardinal State Secretary Luigi Maglione in 1944, worked as a substitute mainly for internal church tasks, his colleague Domenico Tardini dealt with church political tasks. Tardini embodied tradition, while Montini represented "the future" for many.

Pius XII. 1952 put the names of his two co-workers Montini and Tardini at the top of the new cardinals list and announced this in January 1953 to the cardinals present in the consistory ("Iam erant nomina in primis a Nobis scripta."). After the two candidates had rejected the cardinal dignity, the Pope appointed them pro-state secretaries in 1952 (without the rank of bishop and without cardinal dignity). Two years later, after the death of Cardinal Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster , he surprisingly sent Montini, who had often written and made speeches on behalf of the Pope , as Archbishop to Milan . The reason for his removal from Rome could have differences with Pius XII. have been. According to another opinion, Pacelli deliberately wanted to pass on pastoral experiences to his co-worker. The episcopal ordination was donated to Montini on December 12, 1954 in St. Peter's Basilica by Cardinal Eugène Tisserant with the assistance of Bishops Giacinto Tredici of Brescia and the Milanese Auxiliary Bishop Domenico Bernareggi ; the Pope, prevented by illness from doing this himself, took part in the celebration with a radio address. Montini now devoted himself with all his might to the city pastoral care in the northern Italian metropolis. His main focus was on the working class and the building of new churches, for which he gave away his private fortune.

During the pontificate of the already seriously ill Pius XII. Montini had, because of his proximity to the left wing of the Italian Democrazia Cristiana party (around Amintore Fanfani ) suspected of being “socially liberal”, strong opponents in the Roman curia and its surroundings. He supported the lay organization Opus Dei , which at the time was regarded as innovative, also against the activities of leading Jesuits who were then integrally oriented .

Act as a cardinal

After the death of Pope Pius XII. Montini was traded as a "papabile", although he was not a cardinal. He only got the cardinal's hat on December 15, 1958 by John XXIII. and was admitted to the college of cardinals as a cardinal priest with the titular church Santi Silvestro e Martino ai Monti . During this time, Montini toured Brazil and the United States in 1960, and in 1962 he visited Ghana , Sudan , Kenya , the Congo , Rhodesia , South Africa and Nigeria . The cardinal spent several vacations in the Benedictine Abbey of Engelberg Monastery in Switzerland .

In the course of the Second Vatican Council , at which Montini was a member of the commission for the extraordinary tasks, he held back (aware of the risks of this meeting) in public and in the council hall and spoke only twice to the assembled bishops. Behind the scenes, however, the cardinal was very active in persuading the programmatic organization of the council. John XXIII, who valued his co-worker very much, had intentionally not given a narrow direction so that this council could develop its own momentum. However, this openness led to an initial lack of direction among the participants. Montini managed to overcome this critical phase. Some cardinals saw him as a possible successor to the Pope.

Pontificate and Council

After the death of John XXIII. on June 3, 1963, the College of Cardinals met on June 19 to form a conclave . Already in the fifth ballot on June 21, Montini was elected Pope (with 65 of 80 votes, according to Giulio Andreotti ) and took the name of Paul VI. on. The coronation ceremony took place on June 30th in St. Peter's Square. In 1964, Paul VI. took off the tiara and only included it in his coat of arms. He was the last Pope to be crowned with it.

Paul VI led the from his predecessor John XXIII. convened Second Vatican Council to an end. In the epilogue of Pope Paul on the Second Vatican Council it says:

“Since this is the center of the romano cattolico nessuno è, in via di principio, irraggiungibile; in linea di principio tutti possono e debbono essere raggiunti. Per la Chiesa cattolica nessuno è estraneo, nessuno è escluso, nessuno è lontano. […] Questo Nostro universale saluto rivolgiamo anche a voi, uomini che non Ci conoscete; uomini, che non Ci comprendet; uomini, che non Ci credete a voi utili, necessari, ed amici; e anche a voi, uomini, che, forse pensando di far bene, Ci avversate! Un saluto sincero, un saluto discreto, ma pieno di speranza; ed oggi, credetelo, pieno di stima e di amore. "

“In principle, nobody is out of reach from this Roman Catholic center; all can and must be reached. No one is alien, excluded or distant to the Catholic Church. We also address this Universal Greeting to you people who do not know us; does not understand, useful, necessary or considered friends. And also to you, who may be secretly thinking of doing something good if you stand up to us, may today be offered a sincere, unobtrusive greeting, full of hope, respect and love. "

This sums up the Pope's intentions well, but there were other problem areas to be addressed. Paul VI implemented a number of the measures initiated by the Second Vatican Council , such as the liturgical reform . Liberal theologians criticize the fact that Montini opposed a radical democratization of the church energetically. In doing so, he followed the “Petrine principle” of his predecessors, thus understanding obedience to the ecclesiastical office as a prerequisite for dialogue ( encyclical Ecclesiam suam from 1964). The Pope also reformed the Holy Office in 1965 and created the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith from it . With his encyclical Populorum progressio (1967) and the apostolic letter Octogesima adveniens (1971), he made an important contribution to the further development of Catholic social teaching . On June 30, 1968, Paul VI formulated. at the end of the 1900 anniversary of the martyrdom of the holy apostles Peter and Paul in Rome, the Creed of the People of God .

Paul VI decreed many reforms without making a fuss. In order to abolish the 400-year-old institution of the index of forbidden books , a subordinate clause in the order for the redesign of the Holy Office was sufficient in 1965. In October 1966 Paul VI founded also the press office of the Holy See . The apostolic letters Marialis cultus (1974) and Evangelii nuntiandi (1975, following the Synod of Bishops ) took up current theological developments.

The encyclical Humanae vitae from 1968 on the right order of the transmission of human life , in which Paul VI. although on the one hand the consideration of the periods of non-pregnancy by the spouses was considered permitted, on the other hand the use of artificial contraceptives was rejected as "always forbidden". The letter received special attention because the birth control pill was a few years ago. Therefore, opponents of the encyclical gave the Pope the derisive nickname “Pill Paul”.

As a result of Paul VI. initiated changes, in particular the liturgical reform following the Second Vatican Council, the Society of Pius X split off around Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre with around 120,000 followers, as well as various sedevacantist circles (with a few dozen or a few hundred followers each). On the whole, for the first time after a council in modern times, the unity of the church (with around 1.2 billion Catholics today) was preserved.

In 1975 Pope Paul renewed the provisions of the conclave with the apostolic constitution Romano Pontifici Eligendo , published on October 1st . It stipulated that all cardinals who had reached their 80th year of life when a sedis vacancy occurred were no longer eligible to vote. He also affirmed that the number of cardinals eligible to vote should not exceed 120.

Travel abroad as Pope

The foreign and pilgrimages of Paul VI were a novelty in this form. When, on December 4, 1963, at the end of the second session of the Second Vatican Council, Montini announced to the Council Fathers, who had not been prepared for it, that he would go on a trip to the Holy Land from January 4 to 6, 1964 , this came as a surprise, since none for 150 years his predecessors had left Italian soil more (and last around 1814 Pius VII only under the compulsion of Napoléon Bonaparte ). It was to be the first pilgrimage ever made by a Pope to the Holy Land, especially at a time when this territory was politically controversial and dangerous. In addition, the protocol found it a difficult task to complete the preparation in just four weeks. The trip to the holy places in Israel and Jordan received worldwide attention. In Jerusalem , Paul VI met together with Patriarch Athinagoras of Constantinople . This was the first meeting between the heads of Eastern and Western church since the meeting of Pope Eugenius IV. With Patriarch Joseph II. At the Council of Ferrara 1438/39 and led them in 1965 repealing the mutual excommunications between the patriarchates of Constantinople Opel and Rome from the Oriental Schism of 1054. With the trip, the Catholic Church had de facto recognized the State of Israel.

It was the start of many trips abroad by the Pope and his successors. In 1964 Paul VI came. still to India and spoke to the UN General Assembly in New York on October 4, 1965 . The Pope's appeal for peace there is one of his most widely listened political speeches. Further trips took him in 1967 to Fátima and Istanbul (with Selcuk and Ephesus ), in 1968 to Colombia for the opening of the 2nd General Assembly of the Latin American Episcopate. On June 10, 1969 Paul VI was. in genf. He spoke to the international labor organization ILO on the occasion of its 50th anniversary and to the World Council of Churches (Notre nom est Pierre.) . From July 31 to August 2, 1969, Paul VI came. to Uganda ; it was not Montini's first visit to Africa, but the first of a Pope. In 1970 he came to the Philippines and Australia, among others . Paul VI escaped on November 27, 1970, the second day of his last trip abroad through Asia and Oceania. in the Philippine capital of Manila only just about the knife attack by the presumably mentally deranged Bolivian painter Benjamin Mendoza y Amor Flores , who disguised himself as a priest. The Pope was saved from worse by the later American Archbishop Paul Marcinkus and his private secretary Pasquale Macchi . The assassin was later sentenced to prison.

Dialogue and diplomacy

In ecumenical terms, Paul VI. In addition to the dialogue with Orthodoxy, the dialogue with the Old Catholic Church , which had already sent Council observers, continued. While earlier popes from 1723 regularly acknowledged the election advertisements of an Old Catholic Archbishop of Utrecht with a bull of excommunication, Montini wrote for the first time in 1969 a personal congratulatory letter to the designated Old Catholic Archbishop Marinus Kok . In the course of his pontificate several attempts were made to create a regulation for the Old Catholics that almost literally took over the Eastern Church decree. This decree passed by the Council on the Eastern Catholic Churches, Orientalium Ecclesiarum , under nos. 27 and 28, enables the limited communion of the Eucharist between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

In the pontificate of Paul VI. There is also a diplomatic opening towards the communist parts of the world. This was received controversially within the church. Under the leadership of the Bishop of Segni, Luigi Carli , 450 bishops signed a petition to Paul in autumn 1965, in which a new condemnation of communism was requested. On the fringes of the UN General Assembly in 1965, there was an initial informal conversation with the Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Andrejewitsch Gromyko . The following year Gromyko officially requested a meeting with the Pope, which took place on April 27, 1966 in the Vatican. In addition to discussions about the overall global political situation, Montini also called for religious freedom in the countries of the Eastern Bloc at this meeting . In the years that followed, there were several meetings between diplomats from the Holy See and the Soviet Union in Moscow and the Vatican. With this Paul VI moved away. of the strictly anti-communist attitude since Pius XII. , after which contacts with communist states were largely rejected. The aim of the Pope was to alleviate the difficult position of the Catholic Church in the Eastern Bloc through the cautious approach. On January 1, 1968, Paul VI. for this day for the universal Church the World Day of Peace .

Last months and death

On March 16, 1978, the Christian Democratic politician Aldo Moro was kidnapped by the Red Brigades . He and Montini had been friends since Moro's student days; from 1939 he was active in the management of the Catholic student association FUCI, of which the future Pope was once spiritual director. Paul VI personally campaigned for Moro's release by writing a handwritten letter to the kidnappers. But despite these efforts, the politician was eventually murdered; Montini himself later held the mass as part of the state act for Moro.

On July 14, 1978, Paul VI broke. to the papal summer residence Castel Gandolfo. Although his health was in poor health, he met the new Italian President Sandro Pertini there . That same evening the Pope had breathing problems and needed oxygen. The following day (Saturday) was Paul VI. exhausted, but wanted to pray the angelus anyway . However, he was unable to do so and instead stayed in bed. From there, Montini took part in the evening mass. After Communion, the Pope suffered a serious heart attack, of which he died on August 6, 1978 at around 9:40 p.m. Paul VI was buried in the Vatican grottoes , according to his request in an earth grave.

Encyclicals

The five major encyclicals are all thematically related to the Second Vatican Council and clarify current aspects of religious and moral doctrine with greater detail than was possible in the Council documents. In the period that followed, the Pope published further apostolic letters, in particular Octogesima adveniens on Catholic social teaching (1971) and Gaudete in Domino and Evangelii nuntiandi in the Holy Year 1975.

- Ecclesiam suam (August 6, 1964) on the Church's journey today

- Mense Maio (April 29, 1965) on the devotion to Mary in May

- Mysterium fidei (September 3, 1965) on the Eucharist as the center of the Church

- Christi matri rosarii (September 15, 1966) on the rosary as a means of peace

- Populorum progressio (March 26, 1967) on the just progress of peoples

- Sacerdotalis caelibatus (June 24, 1967) on the celibacy of priests

- Humanae vitae (July 25, 1968) on the transmission of human life.

Art orders

Pope Paul VI showed an extraordinary openness to contemporary culture, especially the visual arts. Even in Milan, Montini liked to socialize with intellectuals, artists and writers. With the works of modern religious art he collected, Paul VI. his own department in the Vatican Museums , which he opened in 1973 as the Collection of Modern Religious Art . The museum department includes around 800 works by around 250 international artists. Further works were added to the collection in 1977 as donations from contemporary artists on the occasion of his 80th birthday on September 26, 1977.

Since the Second Vatican Council Paul VI commissioned. several contemporary artists and architects, thus creating new works in the Vatican from 1964–1977. "These [...] include four papal grave monuments and four bronze portals for the St. Peter's Basilica, the papal cross staff, the Vatican audience hall with synodal hall and the papal private chapel in the Apostolic Palace." The bronze Ferula from 1963 was created by Lello Scorzelli.

1964–1971, the Pope had the great Vatican audience hall built by Pier Luigi Nervi (1891–1979). This is usually named after its function (“Aula delle Udienze Pontificie”), its architect (“Sala Nervi”) or today officially after its builder (“Aula Paolo VI”).

Others

Pope Paul VI elevated Albino Luciani (appointed in 1973), Karol Wojtyła (appointed in 1967) and Joseph Ratzinger (appointed in 1977) to cardinals of the three bishops who would later become his successors. Montini himself (like his eight direct predecessors, including all previous popes in the 20th century) had been appointed cardinal by his immediate predecessor. (see list of cardinal creations )

Aftermath

Papal research judged Paul VI that he was misunderstood and hostile by many during his lifetime, although he did not make it easy for himself. In retrospect, it is recognized in many places that Montini surpassed some of his predecessors in reform enthusiasm. He paved the way for his successors. The French philosopher Jean Guitton , who was friends with the Pope, came to the conclusion early on that the achievement of the pontificate would still be discovered by posterity.

The continuation and conclusion of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) named Montini three days before inauguration and coronation (June 30, 1963) as the central task of his pontificate. As a conciliatory "legislator" was Paul VI. the “actual Council Pope”, “not only because he put all the decisions of the Second Vatican Council into effect, but also because his entire term of office was marked by the enormous task of translating the Council into the life of the Church. The importance of the Montini pontificate for all questions of the reception and hermeneutics of the Second Vatican Council is correspondingly great ”.

The Istituto Paolo VI in his hometown Concesio near Brescia is researching his pontificate. It has awarded the Paul VI International Prize since 1983 . In 1984, together with the École francaise de Rome , the Institute published a comprehensive work on him, Paul VI et la modernité dans l'Église .

Canonization process

On May 11, 1993, John Paul II opened the process of beatification for Paul VI. In December 2012, Pope Benedict XVI. the heroic degree of virtue and raised Montini to the venerable servant of God . In December 2013, the Holy See confirmed the recognition of a medically inexplicable healing at the intercession of Paul VI. In mid-February 2014, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints recognized the healing of an unborn child as a miracle. Paul VI was beatified on October 19, 2014.

On March 6, 2018, Pope Francis recognized a miracle necessary for canonization. The canonization of Paul VI. took place on October 14, 2018.

The first liturgical day of remembrance was September 26th, the birthday of Paul VI. With a decree of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Order of the Sacraments of January 25, 2019, Pope Francis ordered the inclusion of the non-mandatory day of remembrance for May 29 in the general Roman calendar . This means that Paul VI has been commemorating Paul VI since 2019. celebrated on the anniversary of his ordination.

Honors

- 1953: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

literature

- Jörg Ernesti : Paul VI. The biography. Herder Publishing House, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-451-35703-9 .

- Ulrich Nersinger: Paul VI. a Pope under the sign of contradiction. Patrimonium-Verlag, Aachen 2014, ISBN 978-3-86417-027-0 .

- Jörg Ernesti : Paul VI .: The forgotten Pope. Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-30703-4 .

- Ralf van Bühren : Art and Church in the 20th Century. The reception of the Second Vatican Council (= Council History , Series B: Investigations). Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-506-76388-4 .

- Michael Bredeck: The Second Vatican Council as a Council of the Aggiornamento. On the hermeneutical foundation of a theological interpretation of the Council (= Paderborn theological studies, 48). Paderborn 2007.

- Jean Mathieu-Rosay: The Popes in the 20th Century. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-89678-531-1 .

- Georg Schwaiger : "In the name of the Lord": Paul VI. (1963-1988). In: ders .: Papacy and Popes in the 20th Century. From Leo XIII. to John Paul II. CH Beck, Munich 1999, chap. VIII. Pp. 344-372, ISBN 3-406-44892-5 .

- Peter Hebblethwaite: Paul VI. The First Modern Pope. Paulist Press, New York 1993, ISBN 0-8091-0461-X .

- Luitpold A. Dorn : Paul VI. The lonely reformer. Verlag Styria, Graz 1989, ISBN 3-222-11808-6 .

- August Franzen , Remigius Bäumer : Papal History. 4th edition. Herder-Verlag, Freiburg 1988, ISBN 978-3-451-08578-9 .

- Aimé-Georges Martimort : Le rôle de Paul VI in la réforme liturgique. In: Le rôle de GB Montini - Paul VI dans la réforme liturgique. Journée d'études, Louvain-la-Neuve, October 17, 1984 (= Pubblicazioni dell'Istituto Paolo VI 5). Brescia 1987, pp. 59-73.

- Philippe Levillain (ed.): Paul VI et la modernité dans l'église (= Collection de l'École francaise de Rome, volume 72). Rome 1984.

- Iosif R. Grigulevic: The Popes of the XX. Century. Urania-Verlag, Leipzig 1984.

- Wilhelm Sandfuchs : Paul VI. Pope of Dialogue and Peace. Echter-Verlag, Würzburg 1978, ISBN 3-429-00588-4 .

- Gustl Kernmayr : Pope Paul VI. The adventure of his youth. Franz Schneider, Munich / Vienna 1971.

- Jean Guitton : Dialogue with Paul VI. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1969.

- Georg Huber: Paul VI. Bonifacius printing works, Paderborn 1964.

- Corrado Pallenberg: Paul VI. Key figure of a new papacy. List Verlag, Munich 1965.

- Andrea Lazzarini: Pope Paul VI. His life and shape. Herder publishing house, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1964.

- Franz Burda (Ed.): Pope Paul VI. in the Holy Land. Burda-Verlag, Offenburg 1964.

- Wilhelm Sandfuchs (Ed.): Pope Paul VI. In nomine Domini (= arena picture pocket book; Volume 7). Arena Verlag, Würzburg 1963.

- Josef A. Slominski, Leone Scampi: Paul VI. From the school of three popes. Paulus Verlag, Recklinghausen 1963.

Web links

- Literature by and about Paul VI. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Paul VI. in the German Digital Library

- The most important of Pope Paul VI. written writings, letters and speeches (partly in German)

- Complete works

- Entry to Pope Paul VI. on catholic-hierarchy.org ; accessed on January 10, 2020.

- Montini, Giovanni Battista. In: Salvador Miranda : The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. ( Florida International University website), accessed November 21, 2019.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Beatification in the Vatican: Paul VI. - reactionary or reformer? ( Memento from October 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Tagesschau.de October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ↑ Cappella Papale presieduta since Papa Francesco con il di Rito Canonizzazione di 7 Beati, October 14, 2018 , Holy See Press Office , Daily Bulletin of 14 October 2018. Accessed October 14, 2018th

- ↑ a b Decree on the start of the liturgical celebration of Pope Saint Paul VI. in the Roman general calendar. In: Daily Bulletin. Holy See Press Office, February 6, 2019, accessed February 6, 2019 .

- ↑ STORIA DI CONCESIO | Concesio . ( brescia.it [accessed October 26, 2018]).

- ↑ Jörg Ernesti: Paul VI .: The forgotten Pope , pp. 28–30; Herder-Verlag, Freiburg 2012.

- ↑ Ernesti: Paul VI. , P. 35, p. 369, Freiburg 2012

- ↑ Ernesti: Paul VI. , P. 37f, p. 369, Freiburg 2012

- ^ Entry on Paul VI. on catholic-hierarchy.org

- ↑ Andrea Lazzarini: Pope Paul VI. His life and shape , p. 169; Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1964

- ^ Lazzarini: Pope Paul VI. , Pp. 90-92; Herder, Freiburg 1964

- ↑ Giulio Andreotti: My seven popes. Encounters in turbulent times , p. 124; Herder, Freiburg 1982. ISBN 3-451-19654-9 .

- ↑ Epilogo del Concilio Vaticano II Ecumenico . December 8, 1965 (full text, Italian)

- ↑ Creed of the People of God »kathnews. Accessed October 7, 2018 (German).

- ^ Paul VI: The Creed of the People of God . Edited and with an introduction by Peter Chrstioph Düren. Augsburg 2018.

- ↑ The Press Office of the Holy See was founded 50 years ago , domradio.de , October 18, 2016

- ↑ Three popes, two conclaves, and an alleged poisoning. Kirchensite.de, Diocese of Münster August 5, 2008. Accessed February 9, 2015

- ↑ Wolfgang Krahl: Ecumenical Catholicism , p. 100; St. Cyprian, Bonn 1970

- ↑ Peter Neuner : New Aspects of the Communion in Communion . In: Wolfgang Seibel SJ (Ed.): Voices of the time . Issue 3 March 1974 , pp. 172-173; Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau.

- ^ Resolutions of the Würzburg Synod, 5.4.1. Eastern Churches and Old Catholic Church, (PDF) p. 214. Homepage German Bishops' Conference , accessed on May 3, 2014

- ↑ Communists: Silence is cowardly . In: Der Spiegel . No. 45 , 1965 ( online ).

- ↑ The Council Pope Paul VI died 25 years ago. Religion.ORF.at August 4, 2003. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ↑ August Franzen, Remigius Bäumer: Papstgeschichte , p. 420; 4th edition. Herder, Freiburg 1988.

- ^ Ralf van Bühren: Art and Church in the 20th Century. , Pp. 319-323, Fig. 18; Schöningh, Paderborn 2008.

- ^ Bühren: Art and Church. , P. 310, Paderborn 2008. To the Paul VI. commissioned works of art and buildings cf. Pp. 310–319, figs. 53–59

- ↑ Michael Bredeck: The Second Vatican Council as the Council of the Aggiornamento. , P. 350, Paderborn 2007; see. Bühren: Art and Church. , P. 302 f, Paderborn 2008.

- ↑ Paul VI. on the way to beatification. RadioVaticana.va December 20, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ↑ Pope Paul VI's miracle Healing called 'unexplainable' putting former Pontiff closer to Sainthood. (English) HuffingtonPost.com December 13, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Theologians approve Paul VI “Miracle”. (English) Vaticaninsider, LaStampa.it February 21, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2015.

- ^ Promulgazione di Decreti della Congregazione delle Cause dei Santi. In: Daily Bulletin. March 7, 2018, accessed March 7, 2018 (Italian).

- ^ Pope Paul VI, Oscar Romero and Katharina Kasper canonized. In: deutschlandfunk.de. Deutschlandfunk, October 14, 2018, accessed on October 14, 2018 .

- ↑ Pope Paul VI. beatified. RadioVaticana.va October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Domenico Tardini |

Substitute at the Vatican State Secretariat 1937–1953 |

Angelo Dell'Acqua |

| Alfredo Ildefonso Cardinal Schuster OSB |

Archbishop of Milan 1954–1963 |

Giovanni Cardinal Colombo |

| John XXIII |

1963–1978 |

John Paul I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Paul VI |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Montini, Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian clergyman, 262nd Pope, Bishop of Rome, Head of State of the Vatican |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 26, 1897 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Concesio near Brescia |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 6, 1978 |

| Place of death | Castel Gandolfo |