Albania in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Albania ( Albanian Mesjeta e Shqipërisë ) was an epoch in the history of Albania that can be classified between the 5th and 15th centuries.

As the Roman Empire in the year 395 in an East - and in one West was divided half, the territory of today came Albania to Byzantium . After that the rulers changed again and again. After barbarians initially conquered the country, it came under the rule of the Bulgarian Empire in the early 840s . At the end of the 12th century, the northern part of Albania became part of the medieval Kingdom of Serbia , which was followed in the 14th century by the Serbian Tsarism , which conquered all of Albania and most of the Balkans. After that, several independent principalities were founded for a short time, which united on March 2, 1444 in the League of Lezha . With the smashing of Shkodra , the last fortress of the League, the alliance was dissolved in 1479 and the Ottomans occupied Albania for over 400 years.

prehistory

After the region of today's Albania in 168 BC. BC final. To the Romans fell, it was in the 3rd century. BC. Part of the province of Epirus nova , which in turn, Macedonia belonged. After the division of the empire , these became provinces of the Byzantine Empire , which were called Thema .

The Byzantine historian Michael Attaleiates mentions in his work Historia (1079 to 1080) Albanoi as a participant in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and Arbanitai as a citizen of the general on the subject of Dyrrachion (today Durrës ). It is controversial whether he was referring to the Albanians in the ethnic sense. Otherwise this would be the first written mention of the Albanian people.

From the 13th century onwards, the name "Albanenses" or "Arbanenses" can be found in sources.

Time of the foreign rulers

Barbarian incursions

In the first decades under Byzantine rule (until 461), Epirus nova suffered from invasions by Visigoths , Huns and Ostrogoths . Not long after this barbarian storm came the Slavs , who at first only undertook raids and looting, but then settled on the entire Balkan peninsula (see Landing of the Slavs in the Balkans ).

In the 4th century the Roman Empire was plagued by raids by various barbarian tribes. The Germanic Goths and the Asian Huns were the first invaders from around 350 onwards. The Avars attacked from 570 and the Slavic Serbs and Croats invaded in the early 7th century. About 50 years later, the Bulgarians conquered most of the Balkans and extended their area of influence to central Albania. The conquerors destroyed Greek, Roman and Illyrian centers on the territory of what later became Albania, including Byllis and Amantia, which was abandoned by the Slavic storm . Thus the development of the early Slavic culture gradually began on the former (east) Roman soil of the Balkans.

Bulgarian rule

The area of present-day Albania became part of the Bulgarian Empire during various periods in the Middle Ages; some regions in the east of today's Albania had been settled and administered by Bulgarians for centuries. Most of Albania was annexed to the First Bulgarian Empire under the rule of Khan Presian I in the early 840s . At this time, the Bulgarians founded numerous cities, but mostly they only expanded an existing settlement (for example Pogradec on Lake Ohrid ). The fortresses of the inner mountain region remained the last strongholds of the Bulgarians for a long time before they were conquered by the Byzantines in 1018 and 1019 during the fall of the First Bulgarian Empire.

For the longest time in this period, some port cities remained in Byzantine hands such as Dyrrachium .

During this time Albania was a center of the Bulgarian resistance against Constantinople (1040-1041):

In 1040 the Bulgarian general Tihomir rebelled against the tax burden of the Byzantine administration in the Durrës region. Soon the rebellion swept across Albania and later united with the rebels of Peter Deljan . After the defeat of the Bulgarians in 1041, the Byzantines took control of Albania again. In 1072 another uprising under Georgi Vojteh (member of the Kawkhanen ) was put down by Byzantium.

Serbian and Venetian rule

The Serbs were able to occupy parts of northern and eastern Albania at the end of the 12th century. In 1204, after crusaders sacked and conquered the Byzantine capital, the Republic of Venice took nominal control of Albania and Epirus . Durrës also came into their possession. In the same year, however, a prince of the overthrown Byzantine ruling family, Michael I. Komnenos Dukas Angelos , was able to conclude various alliances with Albanian tribal leaders and found the Despotate Epirus with the capital Ioannina , which included all of Albania in addition to north-west Greece , only the high mountainous region in the north belonged to Raszien . Komnenos gradually expelled the Venetians from these areas.

But internal power struggles in Constantinople, which was recaptured in 1261, increasingly weakened the Byzantine Empire, so that the Serbian Empire under Stefan Dušan (ruled 1331-1355) became the strongest force in the Balkans and conquered all of Albania. The Serbs later even expanded far into the Greek south of the Balkans.

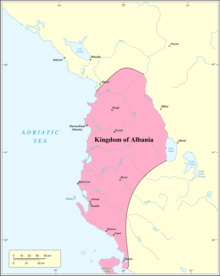

In 1272 Charles I of Naples conquered the port city of Durrës (lat. Dyrrachium ) and founded an Albanian kingdom (lat. Regnum Albaniae ), which during its maximum extent comprised the main part of Albania and the Greek island of Corfu . This empire was rather short lived; Albanian aristocratic families as well as the Serbian Kingdom strove to conquer it. The empire (it only comprised Durrës) was dissolved as early as 1368 when the Albanian Thopia were able to assert themselves in central Albania.

Principality of Arbër / Arbëria

During the Serbian rule, the first Albanian state was founded in the Middle Ages. The Principality of Arbër (or of Arbëria) was founded in 1190 in northern Albania with Kruja as its capital. Progon , later also Gjin and Dhimitër, are called the founders of this state (both sons of Progon, all three together formed the house of Progon). Ndërfandina (place in the Mirdita ) was the most important center of the principality. This is supported by various finds from the Catholic Church of St. Mary (alb. Shën Mëri ). After the fall of the House of Progon, the principality came under the rule of Gregor Kamona and Gulam of Albania . Ultimately, this state was dissolved in 1255 after only 65 years of existence. It reached its heyday under Dhimitër Progon.

Dhimitër Progon was the third and last prince of Albania from the Progon dynasty. He ruled between 1208 and 1216, succeeding his brother Gjin Progon and bringing the principality to its prime. Western sources of the time refer to him as judex (judge) and princeps arbanorum (prince of the Albanians), while Byzantine writings give him the title megas archon (great archon ). He married Komnena, the daughter of the Serbian prince Stefan Nemanja and granddaughter of the Byzantine emperor Alexios III. Angelos , and so got the honorary title of panhypersebast .

The marriage between Dhimitër and Nemanja's daughter did not rule out the threat of Serbian expansion towards Albania. In 1204, however, the more serious danger came from the Venetian Duchy of Durrës, because after the Fourth Crusade successor states to Byzantium were formed, which intended to restore the former empire. In search of allies, Dhimitër signed a pact with the Republic of Ragusa in 1209 and began negotiations with Pope Innocent III. regarding his and his subjects' conversion to Catholicism . This is seen as a strategic move by Dhimitër to forge ties with Western Europe against Venice.

Dhimitër had no son to succeed him. His wife, Komnena, married the Albanian nobleman Gregor Kamona after his death , who later succeeded him. He noticed the gradual decline of the principality and under his successor Gulam of Albania the state ceased to exist.

Regnum Albaniae

After the dissolution of the Principality of Arbëria in 1255, the (First) Kingdom of Albania (Latin Regnum Albaniae ) was founded by Charles I of Naples in its place and other areas conquered by the Despotate of Epirus . In February 1272 he gave himself the title of King of Albania. The empire stretched from Durazzo (Italian for Durrës) south along the coast to Cape Linguetta (near the Karaburun peninsula ) with unclear borders inland. A counter-offensive by the Byzantines soon followed, which resulted in the expulsion of the Capetian house Anjou from the interior in 1281. The Sicilian Vespers also weakened Charles's position and gradually the empire shrank to a small region around Durrës due to the hostile despotate of Epirus, until it was finally conquered by the Albanian prince Karl Thopia in 1368 .

Albanian principalities

The 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century were the times when independent principalities were founded in Albania among Albanian nobles. These principalities emerged between the fall of the Serbian Empire and the Ottoman conquest of Albania.

Principalities in Epirus

In the late spring or early summer of 1359, the battle of Acheloos in Aetolia-Acarnania took place between Nikephorus II Dukas , the last despot of Epirus from the Orsini family , and Albanian tribal leaders under the leadership of Peter Losha and Shpata . The despot was deposed and the Albanians founded three new principalities in the southern territory of the despotate . Since a large number of Albanian leaders the successful campaign of the Serbian tsar Stefan Uroš V , he enlarged the principalities mentioned and, in order to secure their loyalty, he also awarded them the Byzantine title of despot .

The northern state had its capital in Arta and was ruled by the Albanian nobleman Peter Losha. The southern principality was located in Angelokastro ( Lepanto also played an important role, therefore sometimes called the Despotate of Andelokastro and Lepanto) and was ruled by Gjin Bue Shpata.

Both princes received despot titles from the Serbian kings of that time, which is why the states are also known as despotates. After the death of Peter Losha in 1374, the Albanian despotates of Arta and Angelokastro were united under the rule of Gjin Bue Shpata. It stretched from the Gulf of Corinth to the Acheron River in the north and lasted until 1416 when it was conquered by the Ottomans .

Principalities in Albania and Kosovo

From 1335 to 1432 five principalities were founded in these areas. The first of them was the principality of Berat , which was established by the Muzaka in 1335 and, in addition to the city of Berat, also included the fertile Myzeqe plain to the west of it. The Principality of Albania, which emerged from the area of the (First) Kingdom of Albania (Latin Regnum Albaniae ), was the strongest of the five. It was founded by Karl Thopia after the regnum Albaniae was dissolved . The rulers of the principality alternated between the Thopia and Balsha dynasties until 1392 when it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire .

Another important principality was the territory of the castriots , a dynasty founded by Gjon Kastrioti I. It was later conquered by the Ottomans, but again liberated by today's Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. In addition, the principality of Dukagjin , which extended over the Malësia e Madhe to Pristina in Kosovo , was of great importance. The fifth principality was that of the Arianites, who ruled over areas of central Albania.

The battle on the Amselfeld on June 15, 1389, in which some Albanian princes such as Pal Kastrioti and Theodor Muzaka II took part, was historically significant for these principalities . Both fell in this battle. The Battle of the Blackbird Field marked both the beginning of the Ottoman conquest of the Balkan Peninsula and the beginning of a strong defense of the Albanian population that would not end temporarily until 100 years later.

During this time, the first settlement of Albanian refugees in southern Italy took place, whose descendants today form the Albanian ethnic minority of the Arbëresh . Proof of this presence is the plaque to the Albanian commander Giacomo Matranga in the Santa Caterina church in Enna .

When Skanderbeg liberated the central Albanian city of Kruja from the Ottomans and reorganized the principality of the castriots , the successor to Georg Thopia , Andreas II. Thopia , was able to gain control over the principality of Albania. In 1444 various Albanian principalities and counties joined the League of Lezha .

League of Lezha

Under constant pressure from the Ottoman Empire, the Albanian principalities united on March 2, 1444 to form a confederation or confederation . The League of Lezha, named after the place where it was founded, Lezha in northern Albania, was headed first by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg and, after his death, by Lekë Dukagjini . Skanderbeg organized a meeting of Albanian nobles, including the Arianites , Dukagjiner , Spani , Thopia , Muzaka and free Albanian principalities of the mountainous country, in Lezha, where the nobles agreed to fight together against the common Turkish enemy and chose Skanderbeg as their leader. The league did not change the sovereignty of the individual countries, but rather combined them into a defense alliance.

In the light of today's geopolitical science, the League of Lezha represented an attempt to establish a confederation. In fact, however, it was a federation of independent rulers who pursued a common foreign policy in order to defend their independence with a unified army. Of course, all of this also required a joint budget to cover the high military spending; and so each family made its contribution to the League's common fund.

At the same time, each clan retained its property and its autonomy in order to solve the internal problems of its own state. The emergence and functioning of the league was the most important attempt to form an all-Albanian resistance against the Ottoman occupiers, and at the same time an endeavor to establish a short-lived functioning Albanian state.

Under the leadership of Skanderbeg, the Albanian armies marched east and captured strategically important cities such as Dibra and Ohrid . For 25 years, between 1443 and 1468, the 10,000 men of Skanderbeg marched through Ottoman territory, winning one battle after another against the outnumbered and heavily armed Ottoman armies . Ottoman successes in their own homeland motivated Hungary , and later Naples and Venice , to secure financial support from Skanderbeg's army.

On May 14, 1450 a huge Ottoman army stormed and overpowered the city castle of Kruja . This city was particularly important for Skanderbeg, since in 1438 (before his conversion back to Christianity) the Ottomans made him Subaşı (city bailiff) of Kruja. According to the Chronicles of Ragusa (also known as the Chronicles of Dubrovnik ), the siege lasted four months and thousands of Albanian soldiers lost their lives. However, the Ottoman forces were unable to take the city and had no choice but to retreat before winter fell. In June 1466, Sultan Mehmed II (called the Conqueror ) led an army of 150,000 men to Kruja and massacred the Albanian forces. The death of Skanderbeg in 1468 does not mean the end of the struggle for independence, the clashes lasted until 1481, when the Albanian forces under Lekë Dukagjini were defeated by the far superior Ottomans. For his legendary work, Skanderbeg was famous as far as Western and Northern Europe at that time.

Oriental schism

Since the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, Christianity became the dominant religion in the Byzantine Empire. It replaced pagan polytheism and largely eclipsed the humanistic worldview of Greek and Roman civilization, but inherited their institutions. But although the country was under the influence of Byzantium, the Christians of the region remained under the jurisdiction of the Roman Pope until 732. That year, the iconoclastic Byzantine ruler Leo III separated. , annoyed that the archbishops of this region supported Rome in the Byzantine Iconoclasm , removed the Church of the Balkans from the Pope and made her subordinate to the Patriarch of Constantinople. When the Christian Church finally split in 1054 (see Eastern Schism ), southern Albania came to Constantinople while the north fell back to Rome. This division marks the first significant religious fragmentation of the Albanian population.

Culture

The end of the Middle Ages was a heyday for Albanian urban society. Trade abroad prospered to such an extent that leading Albanian traders were able to open their own offices in Venice , Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, Croatia ) and Thessaloniki . The rise of the cities also stimulated the development of education and the arts. However, the Albanian language was not the authoritative language in schools, churches and commerce. Instead, Greek and Latin enjoyed broad and powerful support from the state and church and thus became the main languages in culture and literature.

administration

The new system of governance of the issues may have contributed to the rise of feudalism in Albania as peasant soldiers sacked by their warlords became the owners of land. The leading Albanian aristocratic families included the Thopia , Balsha , Shpata, Muzaka , Arianiti, Dukagjini and Kastrioti. The first three rose to become rulers of principalities that were practically independent of Byzantium.

Web links

- Books about Albania and its people (scribd.com) List of books (and some newspaper articles) about Albania and the Albanian people; whose history, language, origin, culture, literature, etc.

- Library of Congress Country Study of Albania. (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dr. Philipp Charwath: Roman law . Holtzbrinck epubli GmbH, N Berlin 2011, p. 115 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Rob Pickard: Analysis and Reform of Cultural Heritage Policies in South-East Europe . Ed .: Council of Europe. 2008, ISBN 92-871-6265-4 , pp. 16 .

- ↑ Omeljan Pritsak : Albanians. In: Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Volume 1, Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Konrad Clewing, Holm Sundhaussen: Lexicon for the History of Southeast Europe , 2nd edition, Böhlau Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-78667-2 , p. 54.

- ^ A b Raymond Zickel, Walter R. Iwaskiw: The incursions of the barbarians and the Middle Ages in Albania. 1994, accessed October 3, 2011 .

- ^ Yordan Andreev: The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars . Ed .: Abaga. 1996, ISBN 954-427-216-X , pp. 70 (Original title: Balgarskite hanove i tsare, Българските ханове и царе .).

- ↑ Moikom Zeqo: Kur lindi shteti tek shqiptarët? on: albasoul.com

- ^ Mortimer Sellers: The Rule of Law in Comparative Perspective . Ed .: Springer. 2010, ISBN 978-90-481-3748-0 , pp. 207 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b Danila AR Fiorella: Insediamenti albanesi nella Daunia tardo medievale . Centro Grafico Srl, Foggia 1999, p. 4 (Italian, archeologiadigitale.it [PDF; accessed on November 28, 2016]).