Regnum Albaniae

|

Regnum Albaniae Mbretëria e Arbërisë 1272 - 1368 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| navigation | |||

|

|||

| Capital | Durazzo (Dyrrachium, today Durrës ) | ||

| Dependency |

Kingdom of Sicily (1272–1302) Mainland Sicily (1302–1368) |

||

| Form of government | kingdom | ||

| religion | catholic , orthodox | ||

| Head of state |

King Karl I (1272–1285) Karl II. (1285–1294) Prince Philip I of Taranto (1294–1331) Robert of Taranto (1332–1333) Mr. Karl Thopia (1361–1388) Georg Thopia (1388–1392 ) |

||

| Historic era | middle Ages | ||

| Founding of the state | 1272 | ||

| resolution | 1368 | ||

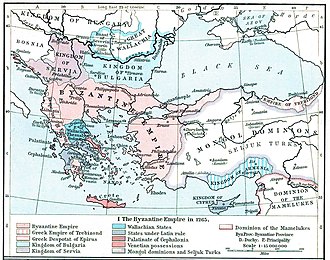

| map | |||

|

|||

The Regnum Albaniae ( Latin for Kingdom of Albania ; Albanian Mbretëria e Arbërisë ) was founded de jure by Charles of Anjou in 1272 in the Albanian areas between Corfu and Durazzo (Dyrrachium, today Durrës ) and was to remain in Angiovino ownership until 1368 .

history

background

The area of today's Albania never formed a political unit in the Middle Ages . The Staufer Manfred , King of Sicily from 1258 to 1266 , resumed the anti-Byzantine policy of the Norman rulers, invaded Epirus in 1258 and occupied Corfu and some coastal towns (Dyrrachium, Valona , Kanina , Buthroton ). Michael II. Komnenos Dukas Angelos , despot of Epirus, managed to persuade Manfred to form an alliance by giving him his daughter Helena as his wife and giving as dowry what Manfred had already conquered. The Staufer rule in Albania was to be short-lived.

In August 1261 the Latin Empire of Constantinople was recaptured by the Byzantines . Pope Urban IV then tried unsuccessfully to initiate a crusade to rebuild the empire. In southern Italy he was in a power struggle against the Staufer king, Manfred, who did not recognize the suzerainty of the Pope, and so the Pope looked for support in the royal houses of Europe, because every future crusade could only have a chance of success if Sicily was supported by one the cause would be governed by the well-meaning king

On May 23, 1265 , the favorite of the papacy Karl von Anjou , brother of the French king Louis IX. , as senator in Rome . On June 28, 1265 , Charles was enfeoffed by Pope Clement IV with Sicily and the "lands on this side of Pharus to the borders of the Papal States, with the exception of Benevento", with the task of conquering the land for the Pope and the last representatives of the To wipe out the Hohenstaufen dynasty (Manfred and Konradin ). On January 6 or 10, 1266, Charles was coronated as King of Sicily in St. Peter's Church in Rome.

Battle of Benevento

Charles invaded the kingdom, defeated and killed Manfred on February 26, 1266 in the battle of Benevento . He had Helena, Manfred's widow, imprisoned. In this way, Charles secured rule over southern Italy and Sicily , claimed Manfred's inheritance (Corfu and the coastal towns of Dyrrachium, Valona, Kanina, Buthroton) and already spoke of his Regnum Albaniae , which was to serve as a bridgehead to the Latin Empire of To re-establish Constantinople and thereby secure control over the entire southern part of the Balkan Peninsula with Greece .

Viterbo Agreement

Agreement with William II of Villehardouin

In agreement with Pope Clement IV, Karl von Anjou concluded a first agreement ( Agreement of Viterbo ) with William II of Villehardouin , Prince of Achaia ( Morea ) in the Pope's residence in Viterbo on May 24, 1267 after lengthy discussions . Wilhelm II, whose forces were exhausted by the fighting with the Byzantine troops and who saw himself threatened by the hatred of the Greek population, recognized the powerful French ruler and neighbor as overlord for Charles' promise of help and engaged his heir Isabelle to Philip of Anjou , Son of Charles. In addition, at his death Achaia should fall to Isabelle's husband or, if the latter should die before him, to Charles or his heirs (Isabelle married on May 28, 1271 in Trani in Apulia . Philip of Anjou, who died in 1277 before his Father died). Instead of getting effective help from Karl, Wilhelm II was to divert forces for Karl to Italy, where on August 23, 1268 he commanded Charles's troops in the battle of Tagliacozzo against the last Staufer, Konradin . In return, he received a promise to help. The Angevin registers are evidence of the tremendous effort Charles made to keep the promise.

Agreement with Baldwin II of Courtenay

Three days later, on May 27, the second Viterbo Agreement was reached in the consent and presence of Pope Clement IV, in which Charles of Anjou and the Latin Emperor Baldwin II of Courtenay, who had been expelled from Constantinople, signed an alliance of friendship and an agreement on partition of the Latin Empire to be conquered. The agreement stipulated that Charles should send 2000 cavalrymen at Baldwin's expense within six years to retake Constantinople and then defend the empire. In return, he should receive a third of the conquered land in the Balkans and the right to the throne of Constantinople, in the event that the succession of Courtenay should be missing. Finally, Karl received Helena's dowry, the land between Corfu and Dyrrachium, which he saw as a legitimate legal claim. Karl immediately had an officer installed in Corfu. To maintain the mainland, however, it took luck and skill.

His daughter Beatrix (* around 1252, † 1275) was betrothed to Philipp (* 1240/41; † December 15 or 25, 1283), Baldwin's only heir. The wedding was to take place on October 15, 1273 in Foggia .

After Baldwin's death in 1273/1274, the Viterbo Agreement was confirmed on November 4, 1274 in Foggia between Charles and his son-in-law Philip.

Battle of Tagliacozzo

On August 23, 1268, Charles was victorious with the help of Wilhelm II von Villehardouin, who commanded Charles's troops with 400 moreotic knights in the battle of Tagliacozzo against the very young Konradin. Konradin's army was defeated, and while on the run he fell into the hands of Anjou, who had him and his closest confidante sentenced to death after a political show trial and beheaded in the market square of Naples . Charles of Anjou resumed the anti-Byzantine policy of the Norman rulers and the Staufer Manfred, who had tried to make Albania the starting point for expeditions against Byzantium .

Formation of the Kingdom

After King Manfred had fallen in the battle of Benevento (1266) against Charles I of Anjou and his widow Helena had been captured, his grand admiral and administrator of the goods of Helena's dowry, Philipp Chinard (* around 1205, † 1266), fled had stayed in Corfu, to Karl's father-in-law Michael II. Komnenos Dukas Angelos, despot of Epirus, because it was clear to him that as Manfred's follower he could only rely on his own strength and the loss of his fiefs (Corfu, Buthroton, Kanina, Valona , Dyrrachium) feared. This fear led him to seek an alliance with the despot of Epirus, who gave him his sister-in-law Maria Petralipha as bride, gave Helena's dowry and shortly afterwards - before October 1, 1266 - had him murdered. The crusader Garnier l'Aleman (Vicar of Philipp Chinard), who took over the administration of Corfu after the assassination of Philipp Chinard, defended the inheritance of the captured Helena. However, since Garnier l'Aleman could not resist the hostile superiority in the long run, he accepted Charles' offer for "the whole island of Corfu with castles with country houses and all the lands of the servants" of land in the Kingdom of Sicily with an annual value of 100 ounces or 1000 Ounces of gold in cash.

Garnier handed the island over to Charles of Anjou in March 1267, who appointed him vicar and captain general on March 20, 1267 and ordered him to invite all Greeks who had left the island since the assassination of Chinard to come home - with the exception of all of them, of course who were involved in the bloody act. The castellan of Corfu Castle , Hugo Chandola, and that of Vallona, Jacques de Baligny, were confirmed. Charles' promise in favor of Garnier could no longer be carried out due to his death. From a document dated May 1272 it emerges that Charles had given the son of the late Garnier, Aimone Aleman, the promised land of the above-mentioned annual value of 100 ounces or 1000 ounces of gold in cash.

Karl left the provisional conditions in Corfu and Epirus in place, but wanted at least factual possession of Helena's dowry from the countries confirmed to him in the Viterbo Agreement. Aleman was initially placed under Wilhelm II of Villehardouin's highness. In 1268 Giovanni Clariaco was sent to Corfu to take possession of the Epirotian estates. Clariaco occupied Valona and Kanina, but left the castellan there, confirmed the fiefs given by Chinard in Corfu and tried in vain to conquer Berat , the center of the Albanian aristocratic family Muzaka . In order to become more easily master of the country, Karl temporarily left Garnier l'Aleman in the possession of the governorship of Corfu, recalled Giovanni Clariaco and appointed Gazo Chinard (brother of the above-mentioned murdered Philipp Chinard) in his place in January 1269 . But Gazo's activity had to be limited to Corfu at first.

With the French princes forced to flee their eastern possessions, Charles prepared in 1269 to retake Greece and other Byzantine territories. In 1269, William II of Villehardouin, the prince of Achaia, conquered the city of Valona, and in the same year Charles agreed a double marriage with the King of Hungary Stephan V , in order to probably the actions of the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII. In this direction to have a handle on.

To strengthen the foundations of the expedition planned for 1270, Charles concluded agreements with King Stefan Uroš I of Serbia , Tsar Konstantin Tich Assen of Bulgaria and the Republic of Venice . The extensive fleet that sailed from Aigues-Mortes on Genoese ships for the planned crusade since the fall of the Latin Empire of Constantinople (1261) had to be diverted to Tunisia when Charles's brother Louis IX. , the King of France, insisted on making his expedition there.

Durazzo , the most important point in Epirus, had been occupied by the despot Michael II, and the Albanians felt they were independent masters there. Charles sent Jean de Nanteuil , the judge Taddeo de Florentia and Aubry de Laon to Albania and asked the chiefs there to pay homage to him as king. The delegates were well received because the majority of the Albanians had long since committed themselves to the Roman Church, of which the Anjou were the patrons.

In 1271 an earthquake in Durazzo caused such a commotion that an Angevin army was able to penetrate the city and thus gain access to the Via Egnatia , which led from there to Constantinople. In the same year a delegation of Albanian nobles and citizens from Durazzo appeared in Naples, worried about being absorbed by the despot of Epirus Nicephorus I , and submitted to Charles of Anjou, who immediately sent troops to Albania under the leadership of Giovanni Clariaco who immediately fortified Kanina and Valona, installed Giacomo Baliniano there as castellan "Iacobi de Baliniano castellani castri nostri Canine et Avallone" ( Domenico Forges Davanzati : Monumenti XLVII, number LI) and he himself became vicar in Corfu: "et confirmazione Iohannes de Clariaco tunc vicarii nostri in ipsa insula "( Domenico Forges Davanzati : Monumenti, number XLIX)

In 1272 Durazzo paid homage to King Charles I, who on February 20 confirmed the citizens their "privilegia antiquorum Imperatorum Romaniae" (prerogatives of ancient Roman Romania ). In addition, Charles declared that he had placed all prelates , nobles and the whole people under his protection. A document from February 1272 granted all citizens and servants of the island of Corfu who wanted to stay security for people and things; and that they could receive and enjoy the lands and goods in their possession without any nuisance according to the customs and traditions of the island.

On February 21, 1272, Charles of Anjou proclaimed the Regnum Albaniae with the center of Dyrrachium (Durazzo) by mutual agreement of the bishops, counts, barons, soldiers and citizens , promising to protect them and to honor the privileges they had received from the Byzantine Empire and proclaimed himself Rex Albaniae . The new kingdom, the territory of which roughly corresponded to the coastline between Dyrrhachion, Valona, Buthroton and Corfu, was ruled by the Neapolitan captains general, who had their seat in Durazzo. On February 25th, Guglielmo Bernardi was appointed marshal of the Neapolitan army under Gazo Chinards “regni Albanie vicario generali” (royal vicar general, deputy). In 1272 and 1273, Charles sent sufficient provisions to Durazzo and Valona, which worried the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII when he found out, so that he sent couriers and inciting letters to the prelates and magnates of Albania so that they could get on with the king Should become enemies of Karl. The latter remained loyal to the Anjou and sent the letters through the vicar general to Charles, who on September 1, 1272 from Monteforte thanked these prelates and magnates in writing for the trust they had received and warned them of Michael's fraudulent methods “quibus, sicut nostis, alias vos decepit “And called on them to support the Angiovinan cause by waging a lively war against the Byzantine enemy. At the same time, Karl gave them news of the success of his ventures.

The Angiovini Offensive (1272)

In 1272 another fleet was ready under Dreux de Beaumont (from 1268 Grand Marshal of Sicily; from 1271 bailiff of Achaia), who was married to a wealthy Achaean heiress, Eve de Cayeux. Gazo Chinard, since 1272 royal vicar general of the Kingdom of Albania and captain general of the Neapolitan army, was sent against Berat. Sufficient troops (Saracens from Nocera ), provisions and money were supplied to him so that he could subjugate the whole country as quickly as possible . For greater security, he should have the Albanians hold him hostage. Everything went according to plan and the Albanians proved their loyalty by voluntarily holding hostages. Berat surrendered in 1273. The prisoners, mostly Greeks, were sent to Trani in Apulia in April 1273 and received a monthly pension for their maintenance. The campaign of 1272/73 was only to be the first in a series to prevent the total disintegration of Achaia and even to temporarily expand the borders.

The reign of Charles of Anjou

The second earthquake in 1273 devastated a large part of Durazzo and many residents were buried under the collapsed houses, others fled to the mountains or to Berat. In the abandoned city, which the governor Gazo Chinard had also left, plundering hordes of Albanians drifted from the mountains. Only four years later the Durazzesi came back from Berat, where they had mostly sought refuge. The city was only established and repopulated under Gazo's successor Anseau de Cayeux , who was sent to Albania to replace him in May 1273, followed by an important mercenary army. New contracts were concluded with Albanian tribal chiefs, for example with Sebastos Paul Gropa (also: Paolo (Paulus) Groppa), whom Karl enfeoffed with various goods outside the Kingdom of Albania. Cayeux also made an agreement with Jacques de Baligny, in which he ceded the castle of Kanina and Valona to the Neapolitan crown against Neapolitan fiefs, which had been confirmed to him for life. Cayeux administered his office only for a short time, because he died in 1273. The high command temporarily went to the leader of the royal troops, Jean de Buffy. In April 1274 the new captain general and vicar, Norjaud de Toucy, was sent to Durazzo to definitively settle the affairs of Albania. Paolo (Paulus) Groppa, Lord of Ohrid , and his father-in-law Gjon Muzaka (also: Gjin; German Johannes ) appeared before the same immediately as "ambassadors of the Albanians", who assured them the devotion of their countrymen. Even so, Toucy made sure to fortify the city and provided Valona with a good crew.

The Council of Lyon (1274)

Michael VIII. Hopes to stop the advance of Charles, were on the influence of Pope Gregory X set. Uniting the Greek (Orthodox) and Latin Churches , the financial preparation of a new crusade and measures for church reform were the three main themes that Gregory X. set himself when he took office (1271). To this end, he announced the Council of Lyon , which took place in Lyon in 1274 . The meeting, which lasted six sessions, determined in the fourth session on July 6th that unity between the churches should be restored. The Pope always refused to give his blessing to the crusade Charles of Anjou wanted to lead to Constantinople and instructed him to postpone its operation.

When the news of the unification of the churches reached Constantinople, there was an uproar there, because the majority of Greeks preferred to suffer and die for the cause of Orthodoxy. Soon the emperor found that he could not impose his will on either his church or his people. In order to convince the Pope that he was doing his best to enforce the Union, he persecuted and imprisoned his opponents. Not all of them were priests and monks, but included several members of his own family. The Union of Lyons and its aftermath failed to bring Christianity into harmony, but managed to unite various elements of the opposition to Emperor Michael VIII. Pope Gregory X died in January 1276 and his successors became increasingly skeptical about the character of the Union.

The Byzantine counter-offensive (1274)

However, the emperor saw no reason why his negotiations with the Pope should prevent him from defending his own borders. So in the spring of 1274 he ordered his western commanders to attack the military bases of Charles of Anjou in Albania. An army sent from Ioannina against Durazzo captured Berat back and became a key position in the Byzantine counter-offensive. The port of Buthroton was captured by the Byzantine army and provided with a strong garrison. Quite a few of the Albanian chiefs joined the emperor, who promised them to recognize their old privileges.

The captain general Norjaud de Toucy tried to win over the majority of the Albanian population, some of whom still maintained their freedoms, by granting them privileges. King Charles voluntarily provided all kinds of subsidies , troops, ships, ammunition, money, grain, salt, etc. This support from the Kingdom of Sicily and Toucy's actions finally determined the chiefs of all Albanian tribes to enter into a convention with Toucy in 1274, which they the Guaranteed privileges. Karl approved the convention on December 1 on the condition that they hold hostages from among them, which they did. Sebasto Maurus Scura, Zacharia and Georg Scura, Sebasto Yonima, Sebasto Paulus Verona, Sebasto Demetrius Scura, Sebasto Blasius, Sebasto Paulos Sanbombruno, Sebasto Yetqui, Sebasto Petrus Misie, Knight Blado Bletista, Sebasto Petrus Clange, Sebasto Tanasius Bessossia appear in the relevant document , Knight Theopea, Sebasto Demetrius Limius, Sebasto Mensis, Sebasto Sarius Barbuca, Sebasto Alexius Arianitis and Knight Paulus. To prove their loyalty, they held hostages who were interned in Aversa on December 13, 1274 . These were Joannes Lallinus, Joannes Grimanus, Tanasius Scura, Minchius Sunbramon, Demetrius Sgura and Zacharias Sgura. In return, the Albanian men and women imprisoned in Bari and Otranto gained their freedom.

And yet some clans opposed the Anjou and hoped for the assistance of the palaeologists , who rearmamented in 1275 to conquer Dyrrhachion and oust the Anjou from Epirus. Gjon Muzaka became one of the main leaders of the Albanian resistance. As an ally of the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, he fought Charles I's expansionist efforts in Albania and was then captured by Charles I on October 11, 1279 with three of his accomplices, Carnesius and Gulielmus Blenisti or Blenishti and the Greek Demitrius Socus (Zûxoç) be taken and brought to Trani.

The Angiovini Counteroffensive (1280)

The Byzantine presence in Buthroton alarmed the despot of Epirus, Nikephorus I, who got in touch with Charles of Anjou and his vassal Wilhelm II of Villehardouin, the prince of Achaia. On June 12, 1276 Wilhelm received the power of attorney from Karl to elicit the oath of homage from his brother-in-law Nikephorus I. In return for his loyalty, Nikephoros was to receive lands in Achaia.

In 1278 the troops of Nikephorus I conquered Buthroton, and on March 14, 1279 Nikephorus declared himself a vassal of Charles of Anjou, handing him not only Buthroton, but also Sopotos ( Borsh ) and Panormos . As a token of his goodwill, he handed his son Michael over to the Angevin castellan of Valona to take him to Glarentza in Morea, where he was to be held hostage.

The details of the negotiation were worked out a few weeks later in several diplomatic talks. The three envoys (Franciscan brother Giacomo, Kirio Magulco, Niccolo Andricopolo) whom Nikephorus had sent to Italy to negotiate the cession of Buthroton came on their way home through Apulia on April 8, 1279. While the ambassadors were in Italy, however, Charles sent two ambassadors (Ruggero di Stefanuzia, Archbishop of Santa Severina , Knight Ludwig de Roheriis) to Nikephoros to draft the text of a formal contract. On April 10, Karl authorized the ambassadors to receive the despot's oath of homage and his signature for the draft on his behalf. However, Karl did not wait for the formalities to be completed and authorized his captain and vicar general of Corfu, Giordano Sanfelice , to ensure the submission of the despot Nikephoros on the same day, not only through the Buthroton castle, but through all castles, villages and lands, which the Staufer King Manfred and his Grand Admiral and administrator of the goods, Philipp Chinard, had once held and which were now in the area of the despotate Epirus . From north to south these were Chimara , Panormos, Sopotos and Buthroton. The final details were prepared by other envoys from Nikephorus who drove home from Barletta and Brindisi on April 12, 1279 .

As a vassal of King Charles of Anjou, Nikephoros continued to rule most of Epirus, from Buthroton to the Gulf of Corinth , but had lost status and territory. Although the Despotate of Epirus was under its native ruler, it was declared a colony of the Angiovini Kingdom of Sicily on the same terms as the Principality of Achaia. The whole east coast of the Balkan Peninsula from Durazzo downward was now under Charles of Anjou suzerainty. Karl made alliances with the northern Balkans, the Serbian King Stefan Dragutin and the Bulgarian Tsar Iwajlo and was almost ready to launch his great offensive along the Via Egnatia from Albania, first to Thessaloniki and then to Constantinople.

Karl tried to get the support of the local Albanian ruling families like the Gropa , Scura , Muzaka, Jonima and Arianiti . In order to maintain this, Charles freed the Albanian nobles who had been imprisoned in Neapolitan prisons since October 1279 (Gjon Muzaka, Carnesius and Gulielmus Blenisti or Blenishti, Demitrius Socus or Zûxoç) and gave some of them Byzantine titles such as that of Sebastokrator . In 1280 "Joannes dictus Musac" (Johannes, called Musac, Gjon Muzaka), who was imprisoned in Brindisi , was released. In return, they had to send their sons to Naples as hostages.

On Charles's orders, dated Lagopesole , August 13, 1279, Charles ordered ships for the embarkation of the newly appointed captain and vicar general of Albania, Durazzo, Valona, Sopocos, Buthroton and Corfu, Hugues le Rousseau de Sully , knight from Burgundy . Sully himself was instructed to go immediately to Brindisi with the sizeable troops under his command and from there to cross over to Albania on August 22nd.

In the following months a major counter-offensive was prepared by the Anjou. Soldiers, including Saracen archers , siege engineers and siege engines , weapons and horses, were transported in huge numbers from Italy to Sphenaritza at the mouth of the Vjosa , where Sully had established his headquarters. The first goal of the expedition was to begin with the recapture of the city of Berat, which had been under Byzantine control since 1274. Sully should make final preparations for the invasion.

Charles's preparations, however, were made by Pope Nicholas III. restricted, who had forbidden Charles to attack the Byzantine Empire. When Pope Nicholas III. died in August 1280, the Pope's seat remained vacant for more than six months, which gave Charles the opportunity to respond. The Emperor in Constantinople still clung desperately to the hope that his Latin enemies would be held back by the Pope. Charles of Anjou achieved a diplomatic victory in February 1281 by securing the election of a French Pope as head of the Catholic Church. The pro-Angevinist Pope Martin IV excommunicated Emperor Michael VIII on November 18, 1281 on the grounds that the Byzantine emperor did not act energetically enough against the opponents of the Union and that he had to be considered "a promoter of the old schism". Charles's expedition against Michael was blessed as a new crusade. At this point, however, the crusade had already begun.

Sully had received orders to attack in the fall of 1280. With his 8,000-strong army, he pushed east along the Via Egnatia. In December 1280, the Angiovinian troops conquered the area around Berat and besieged the fortress of Berat .

The Byzantine counter-offensive (1281)

When the news of the siege of the fortress of Berat reached Constantinople, the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII gathered his reserves and sent them to Berat. They were led by Megas Domestikos Michael Palaiologos Tarchaneiotes and Megas Stratopedarches John Komnenos Angelos Doukas Synadenos . Berat was besieged all winter.

Tarchaneiotes, who arrived there with his army (including Ottoman mercenaries ) in early 1281 , managed to help the hungry besieged garrison and the population by allowing food to flow downstream at night . He was under orders to avoid open combat and focus on ambushes and robberies. The boisterous Sully, who had lost patience with the Byzantine tactics, rode out with only a small bodyguard to scout the Byzantine position. While Sully was out on his horse, he was ambushed by some Ottoman mercenaries from the Byzantine army. His horse was fatally wounded in the process and he was captured. When his men learned that their commander had been captured, they panicked and fled, pursued by the Byzantine cavalry. Only those who crossed the Vjosa River in time escaped and made their way to Kanina, which was Angiovinese. Most of the officers and soldiers of the Angevin army were captured as booty by Tarchaneiotes and his men and led in chains to Constantinople, where, to the great joy of the people, they were led in a triumphal procession through the streets of the city with Sully . The defeat of the Latins at Berat in April 1281 was a famous victory for Emperor Michael, who confirmed his conviction that God was on his side.

The Byzantine army continued its advance by advancing to the Angiovinian bases of Valona and Kanina in the south and Durazzo in the north and besieging them. In December 1281 the captain of Durazzo, Giovanni Scotto, sent urgent appeals to Italy for reinforcements. Reports indicate that the emperor's son, presumably Andronikos , was on his way west with a large infantry and cavalry force. The Albanians of Kruja quickly noticed that change was in the air and sought the friendship of the Byzantine emperor. Michael VIII, who a few days after July 12, 1281 rewarded her with privileges for her city and her diocese.

Giovanni Scotto's successor, Guglielmo Bernardi, who was appointed in May 1283, was the son of a former marshal of the Kingdom of Albania who knew the country well. However, his name disappeared from the records after 1284, and in 1288 Durazzo was apparently in Byzantine hands, because in October of the same year the new emperor Andronikos II renewed the privileges his father had granted the Albanians of Kruja and expressly released them from paying taxes on trading with Durazzo.

The castellan of Valona was praised by Charles of Anjou in September 1284 for his persistent courageous attitude towards the Greeks. In later years the court poet Manuel Philes attributed the recapture of Durazzo, Kruja and Kanina to the heroic action of the protostrator Michael Doukas Glabas Tarchaneiotes , who served under the emperors Michael VIII Palaiologos and Andronikos II in the Balkans. Kanina was probably the last stronghold to fall into the hands of the Byzantines, as there is evidence that Buthroton, which belonged to Corfu, was still under Angevin control in 1292. But in the end Kanina, Valona and Durazzo were all incorporated into the Byzantine Empire.

The plans of King Charles of Anjou

Treaty of Orvieto (1281)

The failure of Hugo de Sully's expedition in early 1281 forced Karl to change his plans. The overland route to Constantinople was now closed to him, so that he had to consider a naval expedition against Byzantium. In 1278 Charles had seized Achaia (see Agreement of Viterbo ) and owned Corfu and other Greek islands. His vassals were the despot of Epirus, Nikephorus I Komnenos Dukas Angelos and the Duke of Athens, John I de la Roche . Karl also had relations with the Serbian King Stefan Dragutin and the Bulgarian Tsar Iwajlo. What was missing, however, was a fleet without which it would have been inconceivable to achieve anything. For this he needed the cooperation of Venice. The collaboration was formalized on July 3, 1281 in the presence of Pope Martin IV between Charles of Anjou, the Doge of Venice, Giovanni Dandolo and the Latin titular emperor Philip of Courtenay in the Treaty of Orvieto . While Venice was to provide the warships, Pope Martin IV provided the moral consent to start the campaign as a crusade for the glory of the faith, the union of the Western and Eastern Churches under the authority of the Pope, the overthrow of the Byzantine imperial dynasty of palaeologists and the restoration to justify the lost Latin Empire of Constantinople “ad recuperationem ejusdem Imperii Romaniae, quod detinetur per Paleologum”. In addition, the contract included the renewal of Venice's old rights and a new crusade for April 1283 at the latest. The Pope gave the company moral legitimation by excommunicating Michael VIII on November 18, 1281.

According to the terms of the treaty, Philip and Karl were to supply an 8,000-strong cavalry and enough ships to transport them to Constantinople. Philip, the Doge of Venice, Giovanni Dandolo, and Karl himself or Karl's son, Charles II , Prince of Salerno , were to personally accompany the expedition. Since Philip had little or no resources of his own, Karl had to provide almost all of the troops. To escort the invasion fleet, the Venetians were supposed to deliver 40 galleys , which should sail from Brindisi no later than mid-April 1283. After Philip's restoration to the throne, he was supposed to grant the concessions of the Treaty of Viterbo of May 24, 1267, allowing Venice to regain all rights and possessions that his people had in Constantinople during the years of Latin occupation, including the recognition of the Doge as lord of a quarter and one eighth of the Latin Empire confirmed.

On the same day in Orvieto another agreement was reached between the three parties, which provided for the organization of an advance guard to precede the main expedition. The Doge was to provide a fleet of 15 warships for seven months, Karl and Philipp were to provide 15 ships and ten cargo ships with around 300 men and horses, which were to gather in Corfu on May 1st. But it should never come to that. The two treaties were ratified by the Doge of Venice on August 2, 1281.

So it seemed that Charles of Anjou had not only united Venice and the papacy, but almost all Balkan powers against Byzantium. The rulers of Serbia and Bulgaria declared their support. The despot of Epiros, Nikephorus I, who was always ready to attack Emperor Michael, joined the coalition of Charles, Philip of Courtenay and the Doge Giovanni Dandolo on September 25, 1281. Thus all of Greece occupied by Latins was on Charles's side. But Michael's diplomacy was up to the opportunity. There were other allies he could turn to. The Genoese were anxious to prevent a renewed Venetian takeover of Constantinople and kept the emperor informed of what was going on in Italy and in the west. The Tsar of Bulgaria, Iwan Assen III. , was Michael's son-in-law, the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt Qalawun promised to lend him ships and the Tartars of the Golden Horde in southern Russia, whose Khan Nogai had married one of Michael's daughters, Eufrosina Paleologa, could keep an eye on the Bulgarians. There was also a Catholic ruler in the west who was known to have personal reasons for hating Charles of Anjou. The Spanish Peter III. , King of Aragon , who married Kostanze , a daughter of Manfred of Sicily, who died in the battle against Karl, made claims to the throne of Sicily. He had a fleet, and his agents were busy instigating an uprising against French Angevin rule in Sicily.

Sicilian Vespers and their aftermath

The reconquest of Constantinople by the French Charles of Anjou was never to take place. The reason for this was an incident of the people of Palermo who attacked French troops on Easter Monday , March 30, 1282, at the time of Vespers in the square next to the Chiesa Santo Spirito , southeast of the city walls of Palermo. This uprising would go down in history as the Sicilian Vespers . The Palermitans attacked every French they could find, spared no man, woman or child and caused the deaths of around 2000 people in the capital alone. The massacre of the French spread day by day and week to week over most of Sicily, with Charles of Anjou's invasion fleet in the port of Messina , which was preparing to sail for Constantinople, also burned to the ground.

The rebels demanded Peter III. von Aragon , husband of Konstanze (only daughter of Manfred, the former king of Sicily), to send an armed force to support them and to become their king. Within a few weeks it was clear that Karl's crusade had to be postponed indefinitely. When on August 30th the Spanish Peter III. of Aragon landed in Trapani and after a march along the coast on September 4th in Palermo was proclaimed King Peter I of Sicily, it was clear that Charles of Anjou had lost the chance to attack Constantinople and establish a great empire . The House of Anjou would lose Sicily forever. Charles' descendants were only able to assert themselves in southern Italy with the main residence in Naples.

Emperor Michael VIII supported the expedition with 60,000 gold pieces. The pro-Angevin Pope Martin IV. Pope responded by telling Peter III. and excommunicated the leading Sicilian rebels and called a crusade against them. The French King Philip III. Who felt this event as an offense for France, used all means at his disposal to avenge this alleged disgrace. Although tens of thousands of soldiers crossed the Pyrenees , Peter III. not be shaken by Sicily.

Charles's son, Charles II, was captured in the Battle of the Gulf of Naples on June 5, 1284 and was still a prisoner when his father died on January 7, 1285. After his death, Charles left all his domains to his son, who was being held in Catalonia at the time and was not released until September 1289.

restoration

The loss of Durazzo

The Anjou lasted for several years in Kanina, Durrazzo and Valona. However, Durrazzo fell into Byzantine hands in 1288 and in the same year the Byzantine emperor Andronikos II renewed the privileges that his predecessor had granted the Albanians in the Kruja area. While Corfu and Buthroton remained in the possession of the Anjou until at least 1292, Kanina Castle fell into Byzantine hands around 1294. In 1296 the Serbian King Stefan Uroš II took possession of Milutin Durrazzo. In order to prevent a future attack by the Serbs on Byzantium, the Byzantine emperor Andronikos II married a then five-year-old daughter Simonida to the Serbian king Milutin, and the lands he had conquered were regarded as dowry.

List of rulers

Kings of Albania

- Charles I (1272–1285)

- Charles II (1285–1294)

Prince of the Kingdom of Albania

- Philip I of Taranto (1294–1331)

- Robert of Taranto (1332-1333)

Dukes of Durazzo

- John of Anjou (1333–1336)

- Charles of Durazzo (1336-1348)

- Joan of Durazzo (1348-1368)

Lords of Durazzo

- Karl Thopia (1361-1388)

- Georg Thopia (1388-1392)

Titular Duke of Durazzo

- Louis of Navarre (1366–1368; 1376)

See also

Web links

literature

- General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts . First Section AG. Hermann Brockhaus, Leipzig 1867 ( full text in the Google book search).

- Arturo Galanti: L'Albania: notes geographic, ethnographic e storiche . Societa editrice Dante Alighieri, Rome 1901 (Italian, archive.org ).

- Etleva Lala: Regnum Albaniae, the Papal Curia, and the Western Visions of a Borderline Nobility . Budapest 2008 (English, ceu.hu [PDF; accessed April 8, 2018]).

Remarks

- ↑ In 1270 Charles II of Anjou married Maria of Hungary and in 1272 Isabella of Anjou married King Ladislaus IV of Hungary .

- ↑ Karolus etc. Per presens scritpum notum facimus universis - tam presentibus quam futuris. Quod nos omnibus burgensibus et ferientibus in insula Curpho volentibus remanere plenam sicuritatem in personis, et rebus eorum tenore presentium elargimur. volentes ut terras et bona que in ipsa insula legitime obtinent habeant et possideant sine molestia qualibet ..... usum et consuetudinum insule supradicte. (Monumenti S. XLIII, number XLIII.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Etleva Lala, p. 12

- ↑ Peter Bartl: Albania - History. Retrieved April 8, 2018 .

- ^ Franz Fiedler: Historical-genealogical tables of the most important regent houses in the Middle Ages and in more recent times . Joh. Ad. Klönne, Wesel 1834, p. 19 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Joseph F. Damberger: Synchronistic history of the church and the world in the Middle Ages . tape 10 . Ms. Pustet, Regensburg 1857, p. 883 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Christian Daniel Beck : Instructions for the knowledge of the general world and peoples history . tape 3 . Weidmann, Leipzig 1802, p. 469 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Joseph F. Damberger, p. 890

- ↑ Alain Demurger: The last Templar: life and death of the Grand Master Jacques de Molay . CH Beck, Munich 2015, p. 56 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts . First Section AG. Hermann Brockhaus, Leipzig 1867, p. 263 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ Günter Prinzing: Villehardouin . In: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe . tape 4 . Munich 1981, p. 414 ff . ( ios-regensburg.de ).

- ^ A b c Jean Dunbabin: Charles I of Anjou: Power, Kingship and State-Making in Thirteenth-Century Europe . Routledge, London / New York 1998, ISBN 978-0-582-25370-4 , pp. 91 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Georg Ostrogorsky: Byzantine History 324–1453 . CH Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 978-3-406-39759-2 , pp. 349 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Jean Dunbabin, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Jonathan Harris: Byzantium and The Crusades . Hambledon Continuum, New York 2006, ISBN 1-85285-501-0 , pp. 178 (English, online version in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b c Jean Dunbabin, p. 90

- ↑ a b Ignazio Ciampi: Cronache e statuti della città di Viterbo . Cellini e Co., Florence 1872, p. 370 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Regione Puglia (ed.): Vita religiosa ed ecclesiastica a Barletta nel Medioevo . Barletta 1993, p. 58 (Italian, pugliadigitallibrary.it [PDF; accessed April 12, 2018]).

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: History of the city of Athens in the Middle Ages . CH Beck, Munich 1980, ISBN 978-3-8496-4078-1 , p. 211 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Günter Prinzing, p. 415

- ↑ a b Konrad Clewing, Holm Sundhaussen: Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe . Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-78667-2 , p. 54 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c Peter Herd: Carlo I d'Angiò, re di Sicilia. In: Treccani.it. Retrieved April 16, 2018 .

- ^ A b c d Camillo Minieri Riccio: Genealogia di Carlo I di Angiò: prima generazione . Vincenzo Priggiobba, Naples 1857, p. 50 (Italian, archive.org ).

- ^ A b c d Robert Elsie: A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History . IB Tauris, London, New York 2012, ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3 , pp. 81 f . (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts, 1867, p. 298

- ↑ a b c d General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts, 1867, p. 299

- ↑ Johann Georg von Hahn: Journey through the areas of the Drin un Wardar . Imperial and Royal Court and State Printing Office, Vienna 1867, p. 276 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Domenico Forges Davanzati: Monumenti . In: Dissertazione sulla seconda moglie del re Manfredi e su 'loro figlioli, Filippo Raimondi . Filippo Raimondi, Naples 1791, p. XLVII, number LI (Latin, archive.org ).

- ^ Domenico Forges Davanzati: Dissertazione sulla seconda moglie del re Manfredi e su 'loro figlioli, Filippo Raimondi . Filippo Raimondi, Naples 1791, p. 37 (Italian, archive.org ).

- ^ Monumenti, SS XLVI, number XLIX

- ^ A b Johann Georg von Hahn : Journey through the areas of the Drin un Wardar . In: Memoranda of the Imperial Academy of Sciences . Second division. tape 16 . Imperial and Royal Court and State Printing House, Vienna 1869, p. 88 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Domenico Forges Davanzati, p. 36 f.

- ↑ Camillo Minieri Riccio, Document No. XIV, p. 140.

- ↑ Peter Bartl: Albania - History. Retrieved April 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Donald M. Nicol: Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations . University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 978-0-521-42894-1 , pp. 15 .

- ↑ Kenneth Meyer Setton: The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571: The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries . tape 1 . American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia 1976, ISBN 0-87169-114-0 , pp. 109 (English, online version in the Google book search).

- ↑ Camillo Minieri Riccio, p. 49.

- ^ Nicholas Petrovich: La rein de Serbie Héléne d'Anjou et la maison de Chaourecs . In: Crusades . tape 14 . Ashgate, 2015, ISBN 978-1-4724-6841-3 , pp. 174 (French, preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Arturo Galanti, p. 118

- ↑ a b c d e Johann Georg von Hahn 1867, p. 277

- ↑ a b c d General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts, 1867, p. 300

- ↑ Kenneth Meyer Setton, p. 111

- ↑ a b c d Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations, p. 206

- ↑ Donald MacGillivray Nicol : The Despotate of Epiros 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages . University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-13089-9 , pp. 17 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Skënder Anamali, Kristaq Prifti: Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime . Botimet Toena, Tirana 2002, ISBN 978-99927-1-622-9 , pp. 208 ff . (Albanian).

- ↑ a b Alain Ducellier: La façade maritime de l'Albanie au Moyen age: Durazzo et Valona du XIe au XVe siècle . Institute for Balkan Studies, Thessaloniki 1981, pp. 294 (French).

- ↑ Skënder Anamali, Kristaq Prifti, p. 211

- ↑ Johann Georg von Hahn 1867, p. 278

- ↑ The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 19

- ↑ The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 21

- ↑ a b The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 23

- ↑ a b The Despotate of Epirus 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p 24

- ↑ a b c d e The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 25

- ↑ Skënder Anamali, Kristaq Prifti: Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime . Botimet Toena, Tirana 2002, ISBN 99927-1-622-3 , p. 211 (Albanian).

- ↑ a b c Kenneth Meyer Setton, p. 136

- ↑ Yury Georgij Avvakumov: The emergence of the idea of union: The Latin theology of the high Middle Ages in dealing with the rite of the Eastern Church . Theologie Verlag GmbH I, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003715-6 , p. 300 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 26

- ^ Mark C. Bartusis: The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 1204-1453 . University Press, Pennsylvania 1992, ISBN 0-8122-1620-2 , pp. 84 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ John Carr: Fighting Emperors of Byzantium . Pen & Sword Books Ltd, Barnsley 2015, ISBN 978-1-78383-116-6 , pp. 231 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations, p. 207

- ↑ a b c The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 27

- ↑ a b The Despotate of Epirus 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p 28

- ^ Mark C. Bartusis: The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 1204-1453 . University Press, Philadelphia 1992, pp. 63 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Antonio Musarra: 1284 La Battaglia della Meloria . Editori Laterza, Bari 2018, p. 46 (Italian, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Alexandra Riebe: Rome in community with Constantinople: Patriarch Johannes XI. Bekkos as defender of the Ecclesiastical Union of Lyon (1274) . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 72 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations, p. 209

- ↑ Alexander Gillespie: The Causes of War: Volume II: 1000 CE to 1400 CE . tape II . Bloomsbury, Oxford 2013, ISBN 978-1-78225-955-8 , pp. 148 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Heinrich Kretschmayr: History of Venice . tape II . Verone, 2015, ISBN 978-3-8460-8442-7 , pp. 13 ( online preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Kenneth Meyer Setton, p. 135

- ↑ Kenneth Meyer Setton, p. 129

- ↑ a b c Kenneth Meyer Setton, p. 140

- ↑ a b Alexander Gillespie, p. 149

- ↑ The Despotate of Epirus 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p 33

- ↑ The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 28

- ↑ George T. Dennis, Timothy S. Miller, John Nesbitt: Peace and War in Byzantium . Catholic University of America Press, Washington 1995, pp. 174 (English).

- ↑ The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages, p. 57 ff.

- ↑ Arturo Galanti, p. 122