Political spectrum

A political spectrum is traditionally described using a one-dimensional geometric axis . The two halves of the axis are referred to as left and right . For a more precise classification of political ideologies, different multi-dimensional classification systems are also used today.

One-dimensional models

story

The emergence of the distinction “left” - “right” in the sense of political directional concepts is traced back to the origin of the French National Assembly in the constituent national assembly of 1789. As a result, the seating arrangement no longer reflected the firmly established social hierarchies as in the assembly of the feudal Estates- General , but soon expressed the dynamic of political-ideological disputes. There was a diversification of the political orientations in the National Assembly into a spectrum of opinion between two extremes: the left-hand side le côté gauche marked a revolutionary, republican thrust, while le côté droit represented more reserved, monarchy- friendly ideas. Soon the spatial adjectives “left” and “right” were substantiated and people simply spoke of la gauche and la droite . Within these camps, wing groups quickly formed: l'extrémité gauche and l'extrémité droite . The legislative assembly established with the constitution of 1791 was then already composed of several more institutionalized groups, which, however, are not to be understood as today's parliamentary groups of parliamentary parties, but represented the organization of the political landscape of the French Revolution in clubs. The number of sympathetic members of a club also fluctuated greatly and almost half of the 745 members of parliament did not belong to any of the clubs. The spectrum ranged between the right, monarchist club of the Feuillants and the left Girondists and Montagnards , which included the Jacobin and Cordeliers club in particular .

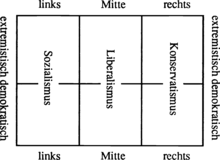

However, the gradually developing language conventions could not take root due to the turbulent development of the revolution . The Jacobins' seizure of power resulted in a rigorous curtailment of the legitimate political spectrum. At the beginning of the restoration phase, the paralysis continued. After the turmoil of the first hundred days, political life quickly renewed itself in 1814. Only now could the geography, which had already developed in the first year of the Great Revolution and which was linked to the parliamentary seating arrangement, revitalize itself. But this was done in slightly different forms: between the camp of "right" and "left" came a translated on balance, moderate-monarchist oriented middle (center) . People still spoke of the extrémités , but now also of the extremes gauche and extremes droite . Even before 1820, the continuum extrême droite - droite modérée - center droit - center gauche - gauche modérée - extrême gauche (ultra right - moderate right - center right - center left - moderate left - ultra left) was part of the established political language.

From France, the left-right distinction spread across Europe. In Germany, the Paulskirchenparliament was constituted according to their model from 1848. Here sat the republican MPs who called for an immediate overthrow of the monarchy at the time, on the left and the proponents of a constitutional monarchy on the right.

Possible opposites

In the classic, one-dimensional model, the contrast between “left” and “right” can represent the various opposites described below.

Egalitarian - elitist

Based on the equality postulate (egalité) of the French Revolution , egalitarian political approaches are central to the self-image of the “left”. They are directed against an actual or systematic disadvantage of identifiable population groups. This initially seemed to be within materially disadvantaged strata of the population ( working class ), but in the course of time it also became apparent in relation to religious or ethnic minorities, women, the elderly, the disabled, homosexuals, people with or without scalp hair, short, plump, or slim, tall people - in other words, in any group of people - identified. The left saw the struggle for political and social equality as part of a progressive striving not only for equality , but also for freedom . Therefore, the term emancipation as a term for the liberation and self-determination of disadvantaged groups is an important point of reference for the self-image of left groups and organizations.

In contrast, the “right” refers to the long existence and practical indispensability of a certain degree of inequality. Either the reasons for this are seen in human nature (talent, ability), or the inequality is explained by means of societal considerations of utility (performance incentive). In addition to the resulting demand for extensive personal freedom for the individual development of the individual for the benefit of society, the organized formation of elites is advocated in this context , from which the management staff of socially significant (political, cultural, scientific and economic) facilities and institutions are sustainably recruited can. In contrast, left-wing, maximally egalitarian concepts are interpreted and rejected as deeply incisive interventions in long-standing individual rights of freedom and development opportunities.

In the democratic constitutional state , once political equality has been achieved, the distribution of social wealth is at the center of the debate about egalitarian and anti-gallant approaches. Differentiations in earnings (primary distribution) are explained with different “talent” and “performance” of the individual. The question of an “appropriate” income-related tax burden (secondary distribution) has become a central practical point of contention in the political debate, since the structuring of taxation is directly in the hands of the legislature and thus takes place in the forum for parliamentary discussion of political currents.

Arbitrary unequal treatment ( discrimination ) on the basis of language, gender, “race”, origin, religion, political opinion or physical disability is in principle outlawed in democratic constitutional states of Western cultural history and character. The core of the ongoing debate remains the question of whether and to what extent the state should take measures to compensate for disadvantages and whether and to what extent the state should counter discrimination in the social field. A distinction is made between equality and equal treatment. For example, parts of today's left to enforce social equality justify measures that are designed as unequal treatment in the sense of improving the position of socially disadvantaged groups (" reverse discrimination ").

Progressive - conservative

In the early days of western democracies, especially in the 19th century, the left strove above all to improve the living conditions of the lower classes, especially the workers , to enforce human rights and thus to continuously renew society. The left propagated this as social progress (progressivity). The right, on the other hand, advocated the preservation of the status quo in relation to political and economic conditions and referred to “traditional” social norms , through which it acquired the designation “ conservative ” (“preserving”).

Several developments today make it difficult to classify according to the terms conservative / progressive: in the western democracies since 1918, right-wing parties have also developed independent programmatic progress concepts and advocated their own policy of technical and social modernization. At the same time it is extremely controversial within and between organizations with a left self-image which conceptions and measures are to be regarded as “progressive”. In addition, after the initial phase of the left movement, the ideological figure of the “defense of progressive achievements” developed, which can be seen as a left variant of conservative approaches.

Internationalist - nationalist

In accordance with the basic egalitarian idea, the left pursued an internationalist approach for a long time , saw itself as a worldwide movement and organized itself internationally . After 1945, however, many left groups saw their task as a “national liberation struggle” and relied on anti- imperialist ideologies. In order to satisfy patriotic emotions in the population, to enforce territorial claims to power or as an expression of an anti-imperialist worldview, even governments with a left-wing self-image represented nationalist approaches. In the context of a critique of globalization , parts of the left today regard the sovereignty of the nation-states as a prerequisite for safeguarding social achievements and mentally position it against the internationality of capitalism .

Until the middle of the 20th century, the right mostly represented a nationalist policy, which since then has differentiated itself into many varieties of regional orientation - but at all times saw itself as an antipole and opposite of left-wing "internationalization", which it saw as a purely ideological plan construct, rejected as impractical and ultimately a hindrance. Against this background, it may not come as a surprise that in the second half of the 20th century the right increasingly found itself to be one of the driving forces behind an economic globalization that was perceived as organic development , which at the same time favored a supra-regional distribution of wealth like a condensation of classic nation-states seems to make possible in diverse organized combinations of smaller-scale cultural and economic regions.

More opposites

While the above-mentioned opposites could at least originally be mapped onto the left-right spectrum, this is not possible or only possible in individual cases in the case of further opposites. A typical example of this is the contrast between “centralist - separatist”. In some states with strong autonomy movements, e.g. B. Spain , there are centralist and separatist parties on both the left and right of the political spectrum .

Classification of political currents

Today's demoscopic studies show that the voters of the individual parties represented in parliament are spread over wide areas of the political spectrum in their self-image. In a poll carried out by Emnid in 2007, 76% of the voters of Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen see themselves as “left”, 39% for the SPD , 25% for the CDU and 23% for the FDP . Overall, 34% of German citizens said they belonged to the “left” on the political spectrum, 52% belong to the “political center” and 11% belong to the right-wing.

conservatism

The “conservative-bourgeois camp” mostly emphasizes the conservative and more rarely the elitist aspect of their own politics in their self-portrayal. Even from the opposition , egalitarian ideas are often advertised, sometimes also to differentiate themselves from liberal positions.

The term right for one's own position is avoided by the conservatives, the term left - if at all - mostly only used disparagingly for political opponents. As in the social democratic and liberal camps, some conservative popular parties are increasingly proclaiming the term “ political center ”.

Social democracy

In the Godesberg program of the German SPD of 1959, the term left was not used explicitly, in the Berlin program it only says in retrospect: "The Social Democratic Party presented itself in Godesberg as what it had been for a long time: the left-wing people 's party." In the 1998 federal election campaign advertised the SPD with the catchphrase "New Center " comparable to the British New Labor . The Hamburg program adopted in October 2007 defines itself as the “ left people 's party”. In the previous Bremen draft from January 2007, the SPD was also defined as the “party of solidarity in the middle ”.

liberalism

The liberalism can be based on this view, hardly a particular political orientation assign right-left scheme because on the one hand very strongly promotes equal rights, performance-related social differences but advocated as an incentive for personal commitment. Often the liberals oppose the antithesis of elitist-egalitarianism with the antithesis of liberal-regulative. Liberals strive for the greatest possible self-determination and personal responsibility of the individual in areas of personal as well as economic life . Social liberals want to correct socially determined inequalities in a compensatory way. They want to answer the social question through qualifications, a state-sponsored education policy and a social market economy .

In Germany and other European countries, parliamentary liberalism is sometimes classified as politically “right-wing” or “bourgeois” due to its economic proximity (“fair performance”).

socialism

Many European socialists now define themselves directly using the left attribute . This is most clearly expressed in the fact that many parties directly refer to themselves as the Left Party .

In Germany, the Democratic Socialism Party renamed itself Die Linkspartei.PDS in 2005 ; through the merger with the WASG , the party Die Linke emerged in 2007 .

In Austria in 2000 the Trotskyists founded the Socialist Left Party , which acts as a further party to the left of the Social Democrats alongside the older, larger and more successful KPÖ ( Communist Party of Austria ) in elections . In the course of the preparations for the 2008 National Council election, a left-wing project was set up , which, following the example of the German Left Party , is supposed to unite left-wing social democratic and trade union forces as well as other left-wing forces in the SPÖ .

Green

Ecological positions are not necessarily linked to traditionally “left” positions. For example, the Greens in Latvia are more conservative, as is the ÖDP in Germany. The civil rights activists of Bündnis 90 , which merged with the all-German Greens in 1993, saw themselves rather “left”, but radically differentiated themselves from the PDS .

In Switzerland, bordering green liberals from the Greens by a liberal economic policy and a more restrictive fiscal and social policy from.

Radicalism and extremism

There is an additional gradation using the attributes radical and extreme . According to the definition of the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, radicals strive for fundamental changes to the social and economic order, whereby they are based on the constitution. Extremists, on the other hand, are directed against the free democratic basic order .

According to Seymour Martin Lipset and Earl Raab, extremism means “anti-pluralism” and “closing the political market”. According to this, center extremism is also conceivable for Lipset .

criticism

Strong simplification

A major criticism is the extreme simplification of the political landscape by projecting various programmatic differences onto a single axis. For the philosopher Johannes Heinrichs , "[t] he operating on the one-dimensional axis of left and right ... is not just outdated today, not just unsuitable, but disruptive to peace and anti-progressive." In addition, it is criticized that the term spectrum suggests a continuity (such as the color shades of the light spectrum ), although ideologically “neighboring” political currents can also show clear fault lines and the individual political-ideological orientations by no means always merge seamlessly into one another.

Correlation between goals and methods

The use of these attributes indirectly creates a positive correlation between the radicality of ideas (i.e. how much they deviate from the status quo) and the vehemence with which they are represented (latent or open violence against those who think differently or the state). Although this correlation is naturally present to a certain extent (the parties in the center usually have the support of the executive , judiciary and media and do not themselves require any extreme measures), it is by no means mandatory. There are moderate groups with radical ideas and aggressive advocates of generally accepted views.

Two-dimensional models

Model after Maurice C. Bryson and William R. McDill

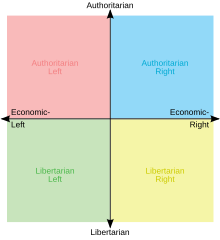

The model published in 1968 by Maurice C. Bryson and William R. McDill locates political positions in a two-dimensional model, which is made up of a vertical statism - anarchy axis ("statism" - "anarchy" axis), which records the extent of state intervention , as well as a horizontal left-right axis (“Left” - “Right” axis), which represents the desired level of egalitarianism.

The model became known to a wider audience in the form of the so-called “Political Compass”, a self-test for positioning in the political spectrum on a website of the same name. In contrast to the original version of the model, the “Political Compass” uses the terms authoritarianism and libertarianism (→ Libertarianism and Libertarian Socialism ) for the vertical axis that measures the extent of state intervention .

Nolan diagram

The Nolan diagram created in 1969 also shows political attitudes on a two-dimensional diagram. Economic freedom is shown on one axis and negative social freedom on the other . It comes from libertarian circles and is not highly regarded outside of them. The structure of the Nolan diagram can be traced back to the model according to Maurice C. Bryson and William R. McDill.

Horseshoe scheme

The horseshoe scheme (also known as the horseshoe model ) does not represent the political landscape as a horizontal straight line, but rather as a horseshoe shape : an incomplete circle with adjacent endpoints. Due to structural similarities, it shows a closeness between left and right-wing extremism (see extremism ).

This representation is intended to express that extremist political attitudes of actually opposing camps are often closer to each other than to the politically moderate forms of their respective field. It is not the right-left antagonism that is decisive, but the relationship to the democratic constitutional state. Eckhard Jesse writes: “The horseshoe picture illustrates this. A characteristic of extremisms is inter alia. the restriction or denial-bearing elements of the democratic constitutional state such as pluralism, the affirmation of a friend-enemy thinking, the acceptance of a high level of ideological dogmatism and social homogeneity, orientation in conspiracy theories and the belief in historical laws. " However, not could summarize every extremism in a left-right scheme, religious extremism such as Islamism eludes such a classification and in this respect cannot even be grasped by the horseshoe.

Various aspects are criticized in this idea, such as a possibly misleading term "center" according to Robert Feustel - which has meanwhile also been claimed by right-wing extremists who call themselves bourgeois - and an undifferentiated equation of left and right-wing extremism, which, if accurately presented, does not Since left-wing extremist violence is “more” directed against things, right-wing extremists against people have something in common. He does not want to trivialize or legitimize anything - according to Feustel - but only to point out a "very important difference". The “horseshoe model was never up to date” because it would suggest equating left and right. This is "even more absurd today than it used to be", the differences are greater than the similarities and, similar to the US, in Germany, the permeability of bourgeois parties to right-wing extremist positions creates an opposition between progressives and reactionaries

The horseshoe was first used in 1932 in Unleashing the Underworld as an image of the distribution of political forces and the relationship between these forces . A cross-section through the Bolshevikization of Germany used. The authors, the National Socialist sociologist Adolf Ehrt and Julius Schweikert, used the picture as an argument against so-called cultural Bolshevism . Both - from the environment of the Black Front - saw a closeness between the KPD and the NSDAP, which would consist in the common rejection of democratic liberalism: “If you imagine the German parties and currents in the shape of a horseshoe, at whose bend the center and at that The endpoints of the KPD and the NSDAP, the area of the 'Black Front' lies between the two poles of Communism and National Socialism. The opposites of "left" and "right" cancel each other out in that they enter into a kind of synthesis with unanimous elimination of the "bourgeois". The position between the two poles best reflects the tension of the Black Front ”. At that time, the radical right understood the image of the horseshoe positively to emphasize what was in common and what unites with the radical left, the rejection of the pluralistic spectrum of parties.

The picture was quoted in the 1960s by the völkisch author Armin Mohler , from whom the conservative political scientist Uwe Backes took it up in 1989. Since then it has become an integral part of the political discourse. Eckhard Jesse , one of the founders of the extremism theory, occasionally used the metaphor “horseshoe”.

More two-dimensional models

Influence on the seating arrangements in parliaments

German Bundestag

When it comes to the seating arrangements in the German Bundestag , the (pre-) council of elders is traditionally roughly oriented towards the political spectrum.

The FDP was placed to the right of the Union parties in 1949, as it was generally considered right-wing liberal at the time. After a long time neither of the sides wanted to swap, this changed in 2017. After the arrival of the AfD, the FDP did not want to sit next to it and wanted to swap with the Union. This was justified by the fact that it no longer corresponds to the current party spectrum to decree the FDP to the right of the CDU and CSU. That was rejected, however, so that the FDP sat next to the AfD in the 19th Bundestag . After the federal election in 2021, the FDP pleaded again to swap places with the Union parties. On the one hand, as in 2017, this was justified with symbols that this swap would adapt the Bundestag to the political conditions, since the CDU and CSU were to be decreed politically on the right of the FDP. On the other hand, further displeasure was expressed about having to continue to sit next to the AfD, especially since female members of the FDP parliamentary group had to listen to sexually suggestive comments from the ranks of the AfD more often. On December 16, 2021, with the votes of the SPD, Greens, FDP and Left, a new seating arrangement was decided in which the FDP sits to the left of the Union.

To the right of the FDP sat the DP in the first three Bundestag and the AfD from 2017 to 2021. Since 2021, the Union parliamentary groups and the AfD have been sitting to the right of the FDP according to the newly established seating arrangement. In the first Bundestag some MPs from smaller parties and non-attached MPs were still placed to the right of the DP. The MPs who had switched to the GB / BHE sat in the back rows of the first Bundestag, including Union MPs. In the second Bundestag, the GB / BHE sat between the Union and the SPD.

In the first Bundestag, the KPD sat on the far left; from the second Bundestag onwards, this was the SPD. Until 1983, the SPD insisted that no parliamentary group should sit on its left. That is why the Green parliamentary group sits to the right of her, although she was seen as clearly “left” in her early days. When the then PDS moved in in 1990, the SPD no longer existed in its outer position.

- Seating arrangement in the 20th Bundestag

- The Left - SPD - Alliance 90 / The Greens - FDP - CDU / CSU - AfD

National Council (Austria)

In Austria, the seating arrangements of the National Council have nothing to do with the political direction of the parties. The social democratic SPÖ sits on the left, the conservative ÖVP on the right, while the right-wing populist FPÖ traditionally takes the place in the middle, where other parties represented in the National Council are also placed. " Wild MPs ", that is, MPs who do not belong to one of the parties represented in the National Council, receive one of the vacant seats.

- Seating order in the 27th National Council

- SPÖ - THE GREENS - NEOS - FPÖ - ÖVP

National Council (Switzerland)

Since 1995, the seating arrangements in the Swiss National Council have been roughly based on the political spectrum. Before that, the focus was primarily on the language groups. On the left is the SP - GPS in front, CVP in the back - various small parties in front, FDP, the Liberals in the back - and the SVP on the right.

Web links

further reading

- Uwe Backes: Political extremism in democratic constitutional states: elements of a normative framework theory . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 978-3-531-11946-5 , fourth chapter: Typology, p. 247 ff ., doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-322-86110-8 .

sources

- ^ Jean A. Laponce: Left and Right, The Topography of Political Perceptions. Toronto / Buffalo / London 1981.

- ↑ Netzeitung: Every third German feels "left" ( Memento from May 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ SPD party executive (ed.): Hamburg program . Basic program of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Berlin October 28, 2007, item no. 3000085, p. 13 ( Hamburg program ( memento from December 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF]).

- ^ Social Democracy in the 21st Century . "Bremen draft" for a new basic program of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Bremen January 2007, p. 62 ( Social Democracy in the 21st Century ( Memento from February 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF]).

- ↑ Wolfgang Ayaß : Max Hirsch . Social liberal union leader and pioneer of adult education centers . Berlin 2013.

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) . Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution . Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ^ Seymour Martin Lipset, Earl Raab: The Politics of Unreason: Right Wing Extremism in America. Chicago University Press, Chicago 1978, ISBN 0-226-48457-2 .

- ↑ Johannes Heinrichs: The antiquity of left and right. (PDF) In: JohannesHeinrichs.de. Retrieved August 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Bryson, Maurice C .; McDil, William R. (1968). The Political Spectrum: A Bi-Dimensional Approach (PDF). Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought. 4 (2).

- ↑ a b Fabian Falck, Julian Marstaller, Niklas Stoehr, Sören Maucher, Jeana Ren, Andreas Thalhammer, Achim Rettinger, Rudi Studer: Political Compass: A Data-driven Analysis of Online Newspapers regarding Political Orientation . The Internet, Policy & Politics Conference, Oxford September 2018, pp. 2 ( ox.ac.uk [PDF; accessed June 15, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Erick Elejalde, Leo Ferres, Eelco Herder: On the nature of real and perceived bias in the mainstream media . In: PLOS ONE . tape 13 , no. 3 , March 23, 2018, ISSN 1932-6203 , p. e0193765 , doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0193765 ( plos.org [accessed June 14, 2019]).

- ^ Brian Patrick Mitchell, Eight Ways to Run the Country: A New and Revealing Look at Left and Right . Greenwood Publishing , 2007, ISBN 978-0-275-99358-0 , pp. 6–8 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Eckhard Jesse : The term “extremism” - what is the gain in knowledge? | bpb. Federal Agency for Civic Education, accessed on February 21, 2021 .

- ↑ a b Katharina Meyer: Why the horseshoe theory is not up to date , ZDF website, February 14, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Adolf Ehrt, Julius Schweikert: Entfesselung der Unterwelt. A cross-section through the Bolshevikization of Germany. Eckart, Berlin / Leipzig 1932, p. 270.

- ↑ Adolf Ehrt, Julius Schweikert: Entfesselung der Unterwelt. A cross-section through the Bolshevikization of Germany. Eckart, Berlin / Leipzig 1932, here quoted from: Gustav Seibt: Rhetorik: Das Mantra von der Mitte. Retrieved February 21, 2021 .

- ↑ Gustav Seibt: Rhetoric: The mantra of the middle. Retrieved February 21, 2021 .

- ↑ Armin Mohler: The Conservative Revolution in Germany 1918-1932. A manual. 2nd Edition. Darmstadt 1972, p. 59.

- ^ Uwe Backes: Political extremism in democratic constitutional states. In: Political Extremism in Democratic Constitutional States: Elements of a Normative Framework Theory. Springer, Wiesbaden 1989, p. 252.

- ↑ Volkmar Wölk : On the horseshoe trail. In: Junge Welt, March 10, 2020, pp. 12-13.

- ^ Astrid Bötticher, Miroslav Mareš: Extremism: Theories - Concepts - Forms. De Gruyter, Berlin 2012, p. 108.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter in the Süddeutsche Zeitung of August 17, 2006

- ↑ Constanze von Bullion: FDP does not want to sit next to AfD in the new Bundestag. Retrieved October 21, 2021 .

- ↑ FDP will sit next to the AfD in the future. Retrieved October 21, 2021 .

- ↑ Lukas Zigo, Sandra Kathe: FDP no longer wants to sit next to AFD - but neither does the Union. Retrieved October 21, 2021 .

- ↑ Bundestag adopts new seating arrangements. Retrieved December 16, 2021 .

- ↑ The seating arrangements in the Bundestag are documented in the respective Bundestag data manuals. Peter Schindler: Data Handbook on the History of the German Bundestag 1949 to 1982. 1983, pp. 522–524; Data handbook on the history of the German Bundestag 1980 to 1984. pp. 531–532; Data handbook on the history of the German Bundestag 1983 to 1991. pp. 553–554.

- ↑ Swiss Federal Archives SFA: The Confederation, Parliament and the Chairs. Retrieved November 28, 2017 .