Returns of cultural assets of colonial origin

Controversial discussions about the return of cultural property of colonial origin began just a few years after the independence of former colonies in the 1970s. In this case, demands to stand after the restitution of cultural goods from colonial contexts such as sculptures, cult objects, manuscripts or archives and even human remains ( human remains ) by countries or ethnic groupsin Africa, Asia, Oceania or America on the one hand and on the other hand negative statements by representatives of collections and museums, especially in Europe or North America. Since the beginning of the 21st century, such discussions and demands have been expressed again and with greater effect, so that since around 2020 a number of cultural objects have been restituted to Benin, Namibia, Nigeria, Indonesia and Guatemala.

Under restitution of cultural property , cultural heritage or cultural heritage refers to the return or restitution of stolen, illegally expropriated, extorted or forced sold cultural goods to the legitimate former owners or their successors . How and by whom cultural property was stolen from its original context depends on the specific case and is assessed very differently by the institutions, people and commentators involved. This gives rise to legal, (cultural) political or moral discussions about the legitimacy of the claim to the respective cultural asset and its possible restitution.

In addition to the acquisition of cultural objects in colonial contexts, usually a long time ago, theft and stolen goods for the illegal trade in cultural property by private individuals represent a further extensive field of discussions and measures for the protection of objects and often relate to similar geographical origins. However, due to national legislation and international agreements, such as the UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Goods, they are now viewed as clear legal violations and are prosecuted accordingly.

To justify restitutions, information from supranational UNESCO agreements, (art) history, provenance research , international cultural cooperation and the social significance in the countries of origin as well as the respective self-image of collections and museums are used. With the report on the restitution of African cultural assets from public collections in France by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy , this topic has received special attention and dynamism internationally since the end of 2018. The discussions about returns are also in the broader context of the decolonization of museums as well as new, resulting cultural relationships between Europe or North America and the countries of origin in the sense of a common, global cultural heritage.

Definition of cultural asset

As material or immaterial cultural property (English: (in-) tangible cultural heritage or cultural property ) both cultural products of people such as works of art, buildings or objects of daily use as well as natural objects such as geological formations (mountains, landscapes, lakes, etc.) , Skeletons and fossils as well as folkloric customs, myths or languages, insofar as the latter are regarded as part of its history or identity for the cultural self-image of a community.

Colonial background of western collections

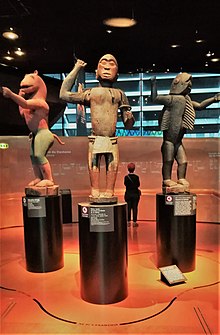

Since the voyages of discovery to non-European continents by European adventurers, soldiers and colonial officials, traders, missionaries or scientists between the 16th and 19th centuries, Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, the German Empire and the British Empire were founded or their forerunners trade and military missions and colonial possessions in areas outside Europe. In addition to raw materials, numerous cultural goods from Africa, Asia and Latin America were brought into trade and private and public collections, especially in the metropolises of London, Paris, Berlin and Brussels. According to Eva-Maria Troelenberg, this exchange of materials and cultural objects resulted in reciprocal processes in that Europe adopted foreign style elements such as Chinese porcelain or oriental carpets and at the same time this cultural appropriation led to new styles in European art such as chinoiseries and orientalist painting .

Against the background of colonial rule , the evaluation and legitimacy of such collections has been controversial since at least the 1960s. Sarr and Savoy describe the annexation of cultural goods in these contexts as a “transgressive act that no legal, administrative, cultural or economic system could legitimize”. Ethnological collections in European or North American museums, such as the Belgian Museum for Central Africa , one of the most extensive collections of cultural and natural heritage from the former colony in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo , are now used as examples of the colonial and violent appropriation of raw materials and mineral resources , but also from culture, history and the documented knowledge of the respective cultures or countries. Cultural studies such as art history , anthropology or ethnology , whose representatives themselves collected human remains such as skulls, hair or other body parts or which at the beginning of the 20th century allowed Africans to be exhibited as exotic beings in so-called Völkerschauen , are also in the Criticism.

African experts like Alain Godonou, director of the Museum Programs in Benin, estimate that around 90% of the cultural assets from the countries of sub-Saharan Africa are in western collections. In the numerous collections and archives in France, there are around 90,000 individual items, of which around 70,000 are in the Africa department of the Musée du quai Branly in Paris.

Historical change in the valuation of non-European cultural assets

As a result of conquests, colonialism or other forms of oppression, looted cultural assets have been displayed as trophies for millennia to prove the superiority of the victors over "inferior cultures".

In their contribution Acquiring Cultures and trading values in a global world from 2018, the authors describe the connections between social and political developments as well as the art trade in Europe with objects of non-European origin by auction houses or specialized dealers and the Museum collections later created from it in the 18th and 19th centuries.

With the end of colonialism and the gradual recognition of the cultural equality of human societies, attitudes towards “trophies” or “curiosities” and the alleged civilizational superiority of Europe have changed. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the appreciation of non-European art and cultures has grown, so that museums, cultural politicians and the interested public now consider such cultural assets as internationally recognized works of art. Today's view of these cultural assets and of the tasks and cooperation between museums and societies of origin is also reflected in the ICOM's ethical guidelines for museums .

In September 2021 , the Louvre Museum opened a special exhibition entitled Venus d'ailleurs on the transfer of culture through collections of non-European cultural assets since antiquity . Materiaux et objets voyageurs . ( From elsewhere. Materials and objects on the move ). In this work of art e presents from prestigious materials such as precious stones, precious woods, mother of pearl, glass or ivory and their ways into European collections and partly as a result of the great scientific and archaeological expeditions from the 18th to the 20th century and the "curiosity about the unknown "Interpreted and referred to as a testimony to the" universal mission "of the museum.

As a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Louvre Museum, Neil MacGregor , former director of the British Museum and one of the founding directors of the Humboldt Forum , gave five public lectures in November 2021 on new demands on museums and their tasks, including on postcolonial interpretations of national Historiography and calls for a decolonization of museums and monuments with a colonial background.

Cultural goods as goods

In June 2021, a group of independent experts in Belgium published Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium with the following comments on the market for cultural goods:

“The existence of an active market for colonizers is often used as an argument against the repatriation of certain colonial collections. However, it is important to consider the conditions in which these markets emerged. Not only were they shaped by local needs, but they also responded directly to the unequal networks of power and capital that colonialism had created. We should not, therefore, underestimate the role that the economic condition of poverty has played in selling items and heirlooms. "

The most recent examples of looted cultural goods from Syria or Iraq and numerous cases of confiscated objects on the websites of the UNESCO Convention mentioned above show that art theft takes place again and again. On the international art market , represented by galleries, auction houses, specialist magazines, collectors, trade fairs and other forms of marketing, non-European cultural objects also achieve high sums.

Since, for example, African sculptures have been interpreted as models for avant-garde art such as Expressionism or Cubism, such sculptures and masks have steadily increased in appreciation by the art trade , museums and private collectors. This not only leads to legal and well-documented sales, but also to counterfeiting, cultural theft, stealing of antiquities and illegal sales with high profit. Museums and their curators not only in Africa, Asia or Latin America were repeatedly victims of art theft in view of the prices on offer.

Provenance research

Provenance research is an effective measure to determine the origin and protection of cultural assets. Although most cultural assets in public collections or on the art market are provided with certain information about their origins and their previous owners, this research area is not just a place for research and documentation, but also systematically studies the culture-specific relationships between the creation, ownership and use of works of art. Even if the documentation of the origin of cultural goods was previously carried out through entries in catalogs, inventory lists and the like, provenance research has been recognized as an important cultural task and an independent cultural studies subject at least since the beginning of the 21st century . The discussion about legal ownership of cultural assets from colonial origins gave rise to new impulses for this subject, which since 2015 has also had chairs at universities such as Bonn, Hamburg, Munich and Lüneburg. Experts who work in this area at public and private institutions have also networked in the provenance research working group .

Even when the origin of cultural goods has been determined, the question of who they should be returned to is sometimes not easy to answer. So in Namibia a discussion arose between the descendants of the national hero Hendrik Witbooi and the National Museum, to whom his bible and whip should be returned by the Linden Museum Stuttgart.

Legal requirements for the protection of cultural property

In the 1970 UNESCO Convention on Measures to Prohibit and Prevent the Inadmissible Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property , the states involved undertake to provide comprehensive protection for cultural property. This also includes international cooperation in the care of cultural assets, museum education and other forms of communication, as well as being recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site . In particular, detailed lists of stolen and restituted cultural assets are continuously documented by UNESCO. Another international instrument for the protection of cultural property from private individuals who bring cultural objects into illegal trade, for example through theft and stolen goods, is the UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Property of 1995. As early as 1978, the UNESCO set up the "Intergovernmental Committee" (ICPRCP) to promote the return of cultural goods to their countries of origin, which has since produced a series of studies, practical guides and the extensive publication “Witnesses to History”. Furthermore, UNESCO publishes information materials for local population groups, young people, art dealers and tourists in cooperation with national partners in order to promote awareness about the protection of cultural property.

In Germany, the Cultural Property Protection Act (KGSG) regulates the corresponding aspects of protection against emigration, import control, trade in and the return of cultural goods. The status of the implementation of cultural protection in 2015 is described by the following quote: “The development in the area of cultural property protection is still in motion, especially in the area of the return of cultural property. Every time the need for further regulations becomes apparent, the international community meets to negotiate appropriate standards (...). The agreements that have already been drawn up as well as the soft law with its ethical and moral dimension lead to a change of heart of the participating states and open the way for more far-reaching rules. As each new agreement is negotiated, the limits of what is possible shift. Aspects that went too far for most market states at the time the UNESCO 1970 Convention was signed are already common practice today due to this change of heart. Nonetheless, the (further) development of the cultural property protection regime is proving to be a tough undertaking that is progressing steadily, but only gradually. "

The German Loss of Cultural Property Center acts as a “central contact for all questions relating to unlawfully confiscated cultural property”. This foundation conducts research and information on Nazi looted art as well as so-called looted art from the Second World War and, since 2018, also on cultural and collection items from colonial contexts. The task of the internationally networked Proveana database is to “support provenance research by documenting historical information”. As part of international coordination with national police authorities, Interpol also maintains a “Stolen Works of Art Database”.

Developments through the Sarr and Savoy report

The speech of French President Emmanuel Macron in Burkina Faso in November 2017, in which he announced the return of African cultural heritage from France, and the report he commissioned by the French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and the Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr on the context and the modalities The restitution of African cultural heritage from France has since represented a milestone in the international discussion. For the first time, a French president and his government recognized a moral right to restitution of cultural goods, which, however, are considered property of the state due to corresponding laws.

On the one hand, African countries such as Benin, Senegal, Nigeria, Mali, Cameroon or Ethiopia had specific expectations of the prompt restitution of their cultural heritage, because they had been demanding this for decades, whereupon legal arguments were always cited as the reason for the rejection. On the other hand, the report does not propose a blanket return of all African cultural goods from France, but rather recommends that diplomatic agreements be made on the restitution of certain important pieces on the basis of proposals by African experts.

In addition, the report names the following measures for a comprehensive reorientation of cultural relations in this area: First through appreciative, international cooperation, through access to research results, archives and documentation also for those interested in Africa or the African diaspora, through exhibitions and educational initiatives for and in Africa as well as with the material support of corresponding networks or infrastructures such as museums and the experts involved, according to Sarr and Savoy, the historical gap between the holdings and research on African culture in France can be reduced through gradual restitution in African countries. A shortened and revised version of this report was also published in German six months later.

As a reaction, since the report was published, the debates between Western and African cultural politicians, museum directors or interested commentators from the press and civil society have moved between affirmative positions on the one hand and merely circulation of objects or even negative positions on the other.

Digitization and online access

As part of the international collaboration between French and African museum experts, Sarr and Savoy proposed the creation of a digital “general inventory of the African collections in the national museums of France”. This is to this information through free access ( open access are available worldwide to them for investigation) - to use and future restitution claims - mainly from Africa. However, in a direct response to this request in the report, Wallace and Pavis of Exeter Law School pointed out the special aspects of such a digital representation. In particular, the authors demanded that African societies or states of origin determine these digital data and receive copyrights , since digital cultural goods and their data are just as important for the future as the restitution of material cultural goods.

The Museum am Rothenbaum - Cultures and Arts of the World (MARKK) in Hamburg announced in June 2020 an international project to digitally merge the globally scattered cultural assets from the historic Kingdom of Benin in what is now Nigeria. The aim of this online project called Digital Benin is "a well-founded and sustainable inventory catalog on the history, cultural significance and provenance of the works".

At the end of November 2021, the German Digital Library (DDB) announced that the online portal “Collections from colonial contexts” had been activated as a pilot project. The domain makes collections from colonial contexts from 25 participating institutions available online within the German Digital Library. The portal was created as “the first, prototypical step on the way to a comprehensive and central digital publication of information on collections from colonial contexts in German cultural and knowledge institutions”. The DDB specified that "the term 'colonial contexts' should not automatically be equated with an injustice context."

International discussions about restitutions

Since the Sarr and Savoy report was published, international reporting has led to an intensive discussion on the subject of restitutions. The two authors were named one of the 100 most influential personalities in the world by the US magazine TIME in 2021 for their influence on the global restitution debate. In the FAZ , the culture journalist Andreas Kilb named Savoy "the most important scientific voice in the debate about the return of African works of art stolen during the colonial era."

On the African side, countries like Benin, Namibia and Nigeria have repeatedly called for the restitution of their cultural heritage since their independence. Official requests from the Republic of Benin and descendants of the Kingdom of Benin in Nigeria ( Benin bronzes ) for cultural goods that reached Europe as spoils of war after the destruction of African royal palaces in Dahomey and Benin City have led to significant restitutions since the end of 2021. In the case of objects that were acquired under different circumstances, such as the so-called Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon in Athens in the possession of the British Museum or the bust of Nefertiti in the Neues Museum Berlin , claims by Greece and Egypt have so far remained unsuccessful, as the museums based on the fact that, based on the case law at the time of acquisition, they rightly own these cultural assets today.

Even if the colonial background of parts of the collections in the British Museum , the Musée du quai Branly or the Ethnological Museum in the Humboldt Forum Berlin is rated as a historical phase of tyranny, some of these museums continue to represent their right to legal ownership of such cultural objects with legal rights Reasons or the argument that such cultural assets can be better protected and presented as a universal museum with international reach than would be possible if they were returned to the societies of origin. Another argument is the assertion that these cultural goods are a general “ shared heritage ” in the sense of the Enlightenment and therefore cannot be claimed as the property of a country of origin.

According to the historian Rebekka Habermas , however, these are “much more than objects that until recently only very few people were interested in. It is also about the question of how Europe relates to its colonial heritage, whether it will continue to be kept silent or whether this part of a very violent history that is still having an impact today is dealt with. "With reference to the demographic developments in Europe towards multi-ethnic societies Not only advocates of the social participation of migrants continue to demand a reassessment of ethnological science and practice in the sense of a decolonization of museums and the view of non-European societies.

Colonial collections and discussions in individual countries

Belgium

In Belgium, the Royal Museum for Central Africa , or AfricaMuseum for short, houses the largest collections with more than 180,000 objects of cultural history and natural history, mainly from the former Belgian colony of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo .

At the opening of the National Museum of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2019, the country's president, Félix Tshisekedi , thanked the former colonial power Belgium for helping the Congo to preserve its heritage in the Belgian AfricaMuseum. At the same time, Tshisekedi advocated an “organized” return of the objects: “It is one thing to ask about the objects, another to store them properly. So the idea is there, but it has to be implemented step by step. It's Congolese heritage so it has to be returned one day, but that has to be organized. "

In the course of the first fundamental renewal in the more than 100-year history of the AfricaMuseum, a decolonization of the collections and demands for restitutions in the former Belgian colonies of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi were taken up. Against the background of the debate about racism in Europe initiated by the Black Lives Matter movement, the large group of African migrants also took part. Furthermore, the influence of the discussion in France led to announcements to change the relevant laws and to more intensive cooperation with representatives of these countries of origin. The publicly accessible collections were supplemented, for example, with elements from the current cultural scenes in the DR Congo. At the end of January 2020, the Advisory Board of the AfricaMuseum adopted guidelines for a restitution policy, which recommended, among other things, a constructive dialogue with countries of origin and civil society, transparent proof of provenance and justified restitution of important cultural objects.

These Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium contain the following statement on the legal hurdles related to restitutions:

“The law should seek to be in harmony with the social and ethical issues of its time and to reflect the demands for justice and reconciliation with the past, which are increasingly resonating in society. A moral obligation to return the colonial heritage is emerging, which invites us to go beyond the limits of the existing legal framework in order to make an ethical responsibility in the law heard. "

In the summer of 2021, the Belgian government passed the transfer of the property rights of more than 800 proven stolen cultural objects to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A further 35,000 objects, the provenance of which has not yet been clarified, lost their status as public property and can be restituted in the future.

Germany

In Germany, despite its relatively short colonial history, which was limited to a few African countries, there is a very large number of African cultural assets in state, municipal or private collections. For example, since 2015 at the latest, the announcement that the holdings of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin will be transferred to the future Humboldt Forum has led to public and academic discussions about the reassessment of colonial history and the colonial collections.

With regard to the evaluation of the existing documents about the acquisition of the so-called Luf-Boot es from the former colony of German New Guinea , a debate arose in 2021 on the basis of the book Das Prachtboot. How Germans stole art treasures from the South Seas between the historian Götz Aly and the Museum of Asian Art (Berlin) . In his book and in an interview with Spiegel about the book, Aly took the view that there was "no evidence" that the German businessman Max Thiel , who later sold this boat to the Berlin Museum, was honest with individual owners or the Hermit Islanders as a tribal community I bought the boat, and believes the purchase of the boat is a result of colonial violence.

The director of the Asian Museum of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation , Lars-Christian Koch , admitted that there was “no document to prove this purchase”. For him, according to Koch, it was “not clear” whether the Luf boat was “illegally acquired” at the time (or not). In his book, Aly described a massacre that the German colonial power had perpetrated on the inhabitants of the island of Luf in the Bismarck Archipelago in 1882/83 , and pointed out that the museum admits that other cultural objects from the same historical context can be proven to have come from a colonial raid .

Even before it opened in 2021, the Humboldt Forum was criticized. Among other things, the accusation was raised of trying to evade the demand for permanent restitutions by referring to thorough provenance research. The Hamburg historian Jürgen Zimmerer took the view that the ongoing efforts in provenance research were a “strategy to put the necessary political decisions on the back burner”. Zimmer also demanded that the burden of proof must be reversed, with colonial collections proving the legitimate acquisition of their holdings, otherwise they should be considered looted property.

The discussion about restitutions z. B. the applications of countries like Namibia or Nigeria for the restitution of objects. After years of diplomatic advances, a Bible and a whip from the possession of the Namibian national hero Hendrik Witbooi from what was then German South West Africa were restituted by the state of Baden-Württemberg at the beginning of 2019 . In May 2019 it was decided that Namibia would get back a historically important stone pillar that was brought to Berlin in 1893. Human remains with cultural value were also returned to the societies of origin from several collections.

From 2016 to 2018, the Linden Museum Stuttgart, in collaboration with the University of Tübingen, researched the museological and scientific handling of colonial objects in ethnological museums. The final report presented in November 2018 focused primarily on the circumstances of the acquisitions by the museum management at the time, colonial officials and other patrons and came to recommendations similar to those of Sarr and Savoy's report.

The fossils of dinosaurs in the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin represent a special case of natural history cultural assets, which were recovered before the First World War in the course of large-scale excavations in what was then German East Africa . Even if it is not denied by either side that these fossils and their history are part of the common cultural heritage of Germany and today's Tanzania , the Tanzanian government does not demand the return of the fossils, but only a partnership in their further research and transfer of knowledge , not only in Germany, but also in Tanzania.

At the beginning of 2019, the Department for International Cultural Policy in the Federal Foreign Office, the culture ministers of the federal states and the central municipal associations presented a joint declaration on how to deal with collections from colonial contexts. The collections in Germany set new foundations for processing, collaboration and returns:

“This gives us a clear framework for planning further concrete steps and measures to deal with collection items from colonial contexts in the following six fields of action: Transparency and documentation; Provenance research; Presentation and mediation; Repatriations; Cultural exchange and international cooperation and contribution from science and research. "

On the occasion of the 2019 annual conference of the directors of the ethnological museums in German-speaking countries, the so-called “Heidelberg Statement” was published as an obligation for future reorientation of these museums. In January 2019, a new department “Cultural and Collection Goods from Colonial Contexts” was created in the “ German Center for Cultural Property Losses ” for the transfer of knowledge and the networking of collections.

In July 2019, the German Museum Association published the second version of a guideline on dealing with collections from colonial contexts . From an explicitly international perspective and based on a workshop with experts from several continents, this guideline offers around 200 pages “German museums and collections a practical tool for dealing with objects from colonial contexts and working with societies of origin - be it the exchange of knowledge or joint projects or returns. "

As early as February 2019 , the cultural critic Thomas E. Schmidt assessed the practical and cultural-political course of the discussion about restitutions in the ZEIT as follows:

"Not everything will return - and 'everything' would not be decolonization either, because it signaled a kind of end to the intellectual exchange between Europe and Africa, a last colonialist gesture by the West, a monstrous fantasy of debt relief."

France

In addition to the world's largest art museum, the Louvre , which has been public since the French Revolution, France also has one of the largest collections of non-European cultural assets, the Musée du quai Branly. At the same time as the planning of the latter museum, a public discussion took place on the question of why the Louvre did not also exhibit cultural objects from ethnographic collections as works of art. As a result, from 2000 onwards , 125 masterpieces from Africa, Asia, Oceania and both parts of America were exhibited in the Pavillon des Sessions, a gallery in the Denon Wing , which are on permanent loan from the Musée du quai Branly's holdings.

Since the end of 2018, the Musée du quai Branly has been the focus of an international debate on the restitution of African cultural goods that were brought to France from former French colonies during the colonial era. After a "keynote address" by the French President in November 2017 on France's policy in relation to Sub-Saharan Africa and due to the government of Benin being required to return the property, the French National Assembly adopted a specific legal regulation for the return ( dérogation ) of 26 cultural objects in December 2020 taken from the palace of Abomey , destroyed by French troops in 1892 . Together with a historical sword that had previously been handed over to the Musée des civilizations noires in Dakar, these objects represent the first permanent restitutions from France under the new law.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam and museums in Amsterdam, Leiden and Berg en Dal house around 160,000 cultural objects of colonial origin. As a superordinate association of these museums, the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National Museum for World Cultures - NMVW) has been coordinating studies on provenance and the cultural-historical background as well as projects for restitution to the countries of origin, such as B. a dagger with gold inlays from the former Dutch colony in what is now Indonesia .

In March 2019, a document entitled Returning Cultural Goods: Principles and Procedures was published to "express the general mission of the museum and reflect the long, complex and multifaceted history that has led to the museum's collections." Obligation to “transparently address and evaluate claims for the return of cultural goods according to the standards of respect, cooperation and timeliness.” In January 2021, the Dutch government approved a central procedure for the return of objects of colonial origin. Following the recommendation of an advisory commission, it announced that it would return all objects in the national collections that had been illegally removed from former Dutch colonies. To this end, a research group of nine museums and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam was announced in June 2021 to develop practical guidelines for Dutch museums on colonial collections.

Austria

In Austria, the problem is particularly affecting the Weltmuseum Wien (formerly the Museum für Völkerkunde), which with around 220,000 ethnographic objects is one of the world's most important museums in this regard. In contrast to other countries, Austria has hardly any direct colonial past; the holdings are mainly based on the collections built by scientifically interested Habsburgs , which consist of acquisitions during expeditions and trips as well as material bought in Europe. Their history could, however, be illegal.

The French initiative and the report by Sarr and Savoy were welcomed at the World Museum. The curator in for Africa emphasized “that there are large gaps in provenance research” and that “donations or acquisitions can never be a license for something to be ethically and morally unobjectionable.” After all, the exhibits have been redesigned since 2018 Weltmuseum is no longer presented as exotic objects, but in the context of documentation and examination of colonial history. Due to Mexico's demand for the return of Moctezuma's feather crown , this specific case has been discussed with the country of origin since the 1990s, but this demand was not met.

The model favored in Austria over a permanent return is based on the idea of shared heritage . This means shared ownership instead of reimbursement or loans to the countries of origin, by means of which resources and interests of both sides (disposal of their own cultural heritage; safe storage, conservation and research; high-profile presence in the other country) could be bundled. To this end, the Weltmuseum has been a member of the international Benin Dialogue Group since 2002 , which was initiated by the then director Barbara Plankensteiner , among others . Although a “Lex Colonial Art” was discussed in parliament in early 2020 in the wake of the Sarr / Savoy report, the situation of provenance research or with regard to restitutions has not changed since then.

United Kingdom

Since the independence of former colonies, museums in the United Kingdom had also received requests for restitution not only from Africa. British museums have also been participating in the Benin Dialogue Group , founded in Berlin, together with experts from the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden since 2008 , and the office of British-Ghanaian architect David Adjaye was commissioned to plan a new museum in Benin City . In 2019, however, the management of the British Museum and the incumbent Minister for Culture spoke out against permanent restitutions. Smaller collections in Aberdeen or Cambridge, on the other hand, began to return individual pieces such as the sculpture of a rooster from the looted Benin bronzes from 2021 .

In the course of the intensified international discussion, a new willingness to work with African experts can also be observed here. That led z. For example, the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University invited experts from Africa to convey their respective views of the cultural assets to British scholars. In September 2020, the museum announced that it had made a number of critical changes to its exhibits and object descriptions, including removing human remains and installing a new introductory area to the museum's colonial heritage. As part of this process, the Pitt Rivers Museum continues to work with communities of origin to fix errors and gaps in existing information and to discuss possible returns.

United States of America

In the USA, too, museums and other collections own cultural assets of colonial origin, which, however, in contrast to the former European colonial powers, were mostly acquired in the art trade or through donations. These are also illegally acquired objects, as the investigations against the New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor showed, for example. For decades he had sold more than $ 100 million worth of stolen antiques from India and Southeast Asia to private collectors and large museums. This included the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute in Chicago and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

In June 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced that it would return sculptures from the booty of the Benin bronzes to Nigeria, and the National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC removed such objects from its exhibition to display them along with other bronze sculptures in its There was also to be restituted. Museums in the USA are mostly only obliged to their supervisory bodies ( Board of Trustees or Regents ) and can surrender their objects in a so-called deaccessioning procedure, regardless of national laws or governments .

Statements on restitutions in African countries

After African countries such as Nigeria, Benin or Namibia had applied for restitution to France, Great Britain or Germany for several decades, positive statements and high expectations can be observed from Africa in response to the Sarr and Savoy report. New applications for restitution, for example from Mali and Nigeria, have already been prepared by binational commissions.

From July 5 to 7, 2019, the Benin Dialogue Group met again in Benin City , Nigeria , at which museums from Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden met with Nigerian partners and representatives of the royal court of Benin work together. In addition to regular professional exchange, there are plans to build a future museum for the famous reliefs and sculptures from the royal palace in what was then Benin, which was destroyed by the British army in 1897.

In Kenya , the “International Inventories Program” (IIP), an initiative of the National Museum in Nairobi in cooperation with local artist groups and the Goethe Institute , operates an online database with more than 30,000 Kenyan cultural objects in western museums. The program thus made the global holdings visible and at the same time indicated their absence to the Kenyan public through an exhibition with empty showcases and corresponding information boards. Since some of these cultural objects are in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne and the Museum of World Cultures in Frankfurt am Main, these museums took over this exhibition from Nairobi in 2021 and some of their Kenyan cultural objects were shown publicly for the first time.

On the other hand, some African curators also reacted critically to the European initiatives regarding returns. Flower Manase, curator at the National Museum of Tanzania in Daresalaam , said that the African experts had to be interviewed first. Because, given the large number of cultural assets and the inadequate equipment of local museums, restitutions are not always a priority. Other African cultural scholars pointed to the ethnocentric character of the institution of museums, which explains why these in Africa usually arouse little interest among local visitors. Another argument concerns the view of cultural heritage in modern, globalized societies, including in Africa. After all, the objects from the museums came from historical cultures with spiritual functions that no longer exist today.

“It's time to fix our stolen identity. (...) But the masks and fetishes that are now stored in European museums - it would be of no use to return them because these pieces are no longer of any value to the Africans. They are empty, dead, lifeless - they have lost their original meaning because they are torn from their context and thus become objects devoid of meaning. Because they weren't art objects, but religious, ritual and magical objects. That was the only reason why they were so important to African societies back then. "

In its statement of December 2021, Are we receiving the restitution we seek? the Ghanaian cultural critic Kwame Opoku welcomed the restitution of the cultural objects from Dahomey to the Republic of Benin as a historic event. At the same time, he emphasized that other important objects from Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Egypt should also be restituted, and called on African experts to describe symbolic returns as inadequate in view of the large number of cultural objects in the global north. In conclusion, he quoted the President of Zimbabwe as follows:

“The affected museums and institutions in the West are called upon to facilitate the ongoing repatriation and restitution efforts with Africa and to cooperate with them. The use of pseudo-measures and terms such as "digital repatriation" and "permanent loan" further violates the philosophy of "do no harm" and the development standards of the technical discussion and thus delays the conclusion of this sad chapter of our history. "

See also

- Ethnological Museum , Berlin

- Musée du quai Branly , Paris

- British Museum , London

- National Museum of African Art , Washington, DC

- Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York City

- Pitt Rivers Museum , Oxford

- Tropical Museum , Amsterdam

- Weltmuseum , Vienna

- List of museums of ethnology , worldwide

- Provenance research on cultural objects from the context of the Boxer War in China

Individual evidence

- ↑ Extensive information on this is available, for example, from the UNESCO publication Witnesses to history. Documents and writings on the return of cultural objects, edited by Lyndell V. Prott, Paris 2009.

- ↑ For differences in the terminology and meaning of restitution, return, repatriation and similar terms, see Prott 2009, pp. Xxi-xxiv and Stamatoudi 2011, pp. 14–19

- ↑ What is meant by "cultural heritage"? In: www.unesco.org. UNESCO, 2017, accessed May 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Sarr, Felwine; Bénédicte Savoy: Give it back. About the restitution of African cultural assets . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-95757-763-4 , pp. 21-22 and 26-29 .

- ^ Eva-Maria Troelenberg: Arts. In: European history online. Institute for European History (Mainz), April 16, 2020, accessed on November 18, 2021 .

- ^ Moritz Holfelder: Our looted property. A pamphlet on the colonial debate. In: www.bpb.de. Federal Agency for Civic Education, November 5, 2020, accessed on November 17, 2021 (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 DE).

- ^ Sarr and Savoy, p. 23

- ↑ Anna Valeska Strugalla: Return of stolen art: “A thing of impossibility” . In: The daily newspaper: taz . May 12, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed November 24, 2021]).

- ↑ Tim Gihring: Confronting the legacy of looting: From colonialism to Nazis, Minneapolis Institute of Art is reckoning with the ancient problem of plunder. In: Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA). May 19, 2020, accessed November 24, 2021 .

- ^ Anne Dreesbach: Colonial exhibitions, Völkerschauen and the display of the "foreign". In: European History Online , Leibniz Institute for European History, Mainz 2012, ISSN 2192-7405 ( Online ; PDF )

- ↑ Eva Maria Troelenberg (2020) commented: "A so-called 'global art history' that focuses on objects and their circulation, for example, also depicts a particularly exposed segment of social and economic contact and conflict history. Such a story shows Europe inevitably not as a constant center, but as a junction of a comprehensive global network, which fundamentally calls into question the traditionally Eurocentric, developmentally shaped categories and narratives of western art and history. "

- ↑ Lyndel Prott V. (eds.): Witness to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects . UNESCO, Paris 2009, p. 61, cited in Sarr and Savoy, p. 204 f .

- ^ Sarr and Savoy, p. 93

- ↑ Bénédicte Savoy, Africa's Struggle for its Art: History of a Post-Colonial Defeat. CH Beck: Munich 2021

- ↑ See also the chapter “ The appropriation of foreign cultural goods: a crime against the peoples” in Sarr and Savoy, pp. 21–24

- ^ Charlotte Guichard, Bénédicte Savoy: Acquiring cultures and trading value in a global world . In: Bénédicte Savoy, Charlotte Guichard, Christine Howald (eds.): Acquiring cultures: Histories of World Art on Western Markets . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-054508-1 , p. 3-4 , doi : 10.1515 / 9783110545081 .

- ^ Helg, Ursula, and Miklós Szalay. "African Art: Its Reception and Aesthetics." Africa in Transition 40 (2007): 223–239

- ↑ Alexis Malefakis: Stranger Things. The reception of African art as cultural appropriation. (pdf) In: Jahrbuch des Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde München, 13th 2009, p. 112 , accessed on 19 November 2021 .

- ↑ ICOM Ethical Guidelines for Museums. In: https://icom-deutschland.de . International Council of Museums (ICOM) Switzerland, 2010, accessed on December 6, 2021 (German).

- ^ Exhibitions - From afar. In: www.louvre.fr. Musée du Louvre, accessed on November 18, 2021 (English, For the quote for the museum's universal mission, see the exhibition catalog: Philippe Malguyres, Jean-Luc Martinez: Venus d'ailleurs. Matériaux et objets voyageurs. Paris: Louvre 2021, P. 11).

- ↑ Alexander Menden: BLM Protests: Statues that are made of stone and metal. In: https://www.sueddeutsche.de . June 11, 2020, accessed December 21, 2021 .

- ^ Neil MacGregor: A monde nouveau - nouveaux musées. In: http://mini-site.louvre.fr . La Chaire du Louvre 2021, accessed December 19, 2021 .

- ↑ Emmanuel Fessy: Les musées doivent changer de syntaxe. In: https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr . December 7, 2021, accessed December 19, 2021 (French).

- ↑ See the original text in English: Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium (June 2021). Accessed December 12, 2021 .

- ^ Michael Goodyear: Keeping the Barbarians at the Gates: The Promise of the UNESCO and UNIDROIT Conventions for Developing Countries . In: Michigan Journal of International Law . tape 41 , no. 3 , August 1, 2020, ISSN 1052-2867 , p. 581–614 , doi : 10.36642 / mjil.41.3.keeping ( umich.edu [accessed November 23, 2021]).

- ↑ Ingo Barlovic: Scars of Time . In: Der Tagesspiegel Online . March 13, 2018, ISSN 1865-2263 ( tagesspiegel.de [accessed November 27, 2021]).

- ↑ Stefan Eisenhofer, Karin Guggeis: African Art. Facts, prices, trends. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-422-06335-8 .

- ↑ Yaelle Biro: African arts between curios, antiquities, and avant-garde at the Maison Brummer, Paris (1908-1914). In: Journal of Art Historiography. 2015, accessed December 25, 2021 .

- ^ The art dealer, the £ 10m Benin Bronze and the Holocaust . In: BBC News . March 14, 2021 ( bbc.com [accessed November 25, 2021]).

- ↑ Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin and Sophorn Kim, Faked biographies. The remake of antiquities and their sale on the art market. In Hauser-Schäublin, Brigitta; Lyndel V. Prott. 2016. Cultural property and contested ownership: the trafficking of artefacts and the quest for restitution . S.108-129 https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781315642048.

- ^ Agnès Bardon: 50 Years of the Fight against the Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Goods. In: unesdoc.unesco.org. UNESCO, 2020, accessed on November 17, 2021 (English, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO).

- ^ Ingrid Thurner: Art as a fetish: on the western reception of African objects . In: Communications from the Anthropological Society in Vienna . tape 127 , 1997, pp. 79-97 ( ssoar.info [accessed November 19, 2021]).

- ^ Provenance Research Network in Lower Saxony. Retrieved November 19, 2021 .

- ↑ Our mission - Provenance Research Working Group. Retrieved on November 19, 2021 (German).

- ↑ Bible and whip go back to Namibia. Deutschlandfunk, February 28, 2019, accessed on November 24, 2021 .

- ^ UNESCO: Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Property. 2017, accessed on May 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Protection of cultural property | German UNESCO Commission. Retrieved November 23, 2021 .

- ↑ Intergovernmental Committee | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Lyndel V. Prott (Ed.) Witnesses to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects. UNESCO: Paris 2009

- ↑ Publications | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Pedagogical and raising-awareness programs | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Protection of cultural property - home page. In: www.kulturgutschutz-deutschland.de. The Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, accessed on November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Splettstößer, Anne and Taşdelen, Alper: The protection of movable material cultural assets on an international and national level In: Culture as property: instruments, cross-sections and case study. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, 2015, accessed on May 13, 2019 .

- ^ German Loss of Cultural Property Center - Tasks. Retrieved November 18, 2021 .

- ↑ Open data for better provenance research | Proveana. Retrieved November 18, 2021 .

- ^ Interpol: Stolen Works of Art Database. Accessed November 24, 2021 .

- ^ Laurent Carpentier: French museums face a cultural change over restitution of colonial objects. November 3, 2014, accessed May 13, 2019 .

- ^ Sarr and Savoy, Schedule for a Restitution Program, pp. 127-134

- ↑ Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy: Return . About the restitution of African cultural assets . Matthes & Seitz Verlag, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-95757-763-4 .

- ^ Anna Codrea-Rado: African Officials Respond to France's Restitution Report. November 30, 2018, accessed May 10, 2019 .

- ^ A b David Sanderson, Arts Correspondent: Minister rules out return of treasures . ISSN 0140-0460 ( thetimes.co.uk [accessed November 24, 2021]).

- ^ Sarr and Savoy, pp. 134-136

- ↑ Andrea Wallace, Mathilde Pavis: Response to the 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report: Statement on Intellectual Property Rights and Open Access Relevant to the Digitization and Restitution of African Cultural Heritage and Associated Materials . ID 3378200. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY March 25, 2019 ( ssrn.com [accessed June 20, 2019]).

- ↑ See also Johannes Britz, Peter Lor: A Moral Reflection on the Digitization of Africa's Documentary Heritage . In: IFLA Journal . tape 30 , no. 3 , October 1, 2004, ISSN 0340-0352 , p. 216-223 , doi : 10.1177 / 034003520403000304 ( sagepub.com [accessed November 29, 2021]).

- ↑ Digital Benin. Accessed December 12, 2021 .

- ↑ MARKK: Digital Benin - MARKK. In: https://markk-hamburg.de . June 4, 2020, accessed December 12, 2021 .

- ↑ ccc.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

- ↑ Online portal “Collections from Colonial Contexts” launched. In: https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de . German Digital Library, November 30, 2021, accessed on November 30, 2021 .

- ↑ TU Berlin: TIME counts Bénédicte Savoy among the 100 most influential personalities in the world. Retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ^ Andreas Kilb: Bénédicte Savoy on looted art: Kulturkampf, first act . In: FAZ.NET . ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed November 24, 2021]).

- ↑ Wolfgang Mulke: The restitution of colonial artifacts is making slow progress. Goethe-Institut, accessed on November 24, 2021 .

- ^ Musée du quai Branly: Bénin, la restitution de 26 œuvres des trésors royaux d'Abomey. Retrieved November 25, 2021 (French).

- ↑ Nadia Khomami: Cambridge college to be first in UK to return looted Benin bronze. October 15, 2021, accessed November 25, 2021 .

- ↑ Newsweek Staff: Who Owns the Elgin Marbles? June 5, 2009, accessed November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Nefertiti remains a Berliner. BZ - Berliner Zeitung, December 3, 2012, accessed on November 24, 2021 .

- ^ British Museum: Collecting and empire trail. Accessed November 24, 2021 .

- ^ Musée du quai Branly: Missions - A bridge between cultures. In: www.quaibranly.fr/. Accessed November 24, 2021 .

- ^ National Museums in Berlin: National Museums in Berlin: Colonialism. Retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ^ Isaac Kaplan: The Case against the Universal Museum. In: www.artsy.net/. April 26, 2016, accessed November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Bredekamp contradicts Savoy's recommendations - "I reject this argumentation of equating". Retrieved November 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Rebekka Habermas: Debates on restitution, colonial aphasia and the question of what Europe is all about. In: www.bpb.de. Federal Agency for Civic Education, September 27, 2019, accessed on November 17, 2021 (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 DE).

- ↑ Kurt Hirschler: Decolonization of Thought . In: The daily newspaper: taz . October 4, 2014, ISSN 0931-9085 , p. 44 ( taz.de [accessed on May 31, 2019]).

- ^ Belgique: la restitution du patrimoine africain en débat - RFI. Retrieved May 31, 2019 (French).

- ↑ VRT news updates from Flanders: President Tshisekedi wants to gradually bring art treasures from the AfricaMuseum back to the Congo. November 24, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019 .

- ^ Restitution policy of the Royal Museum for Central Africa. In: https://www.africamuseum.be . AfrikaMuseum Tervuren, 2020, accessed on December 13, 2021 .

- ↑ Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium (June 2021). Accessed December 12, 2021 .

- ↑ Julia Hitz: Belgium returns colonial looted art to DR Congo. In: https://www.dw.com . June 28, 2021, accessed on December 22, 2021 (German).

- ↑ According to a report by Deutsche Welle on May 18, 2021, the Berlin collections have more than 65,000 exhibits from Oceania alone.

- ↑ Jonathan Fine in conversation with Michael Köhler: Humboldt Forum - "Objects link to colonial history". August 2, 2015, accessed May 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Ulrike Knöfel: Debate about colonial art: Everything is conceivable, just no agreement . In: The mirror . April 21, 2021, ISSN 2195-1349 ( spiegel.de [accessed November 29, 2021]).

- ↑ Felix Bohr, Ulrike Knöfel, Elke Schmitter: Colonies in the South Seas: The German blood trail in paradise . In: The mirror . May 8, 2021, ISSN 2195-1349 ( spiegel.de [accessed December 9, 2021]).

- ↑ Götz Alys allegations of looted art relating to the Luf-Boot - Museum in the Humboldt Forum admits that there have been omissions. In: https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de . Retrieved December 9, 2021 .

- ^ Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com): Luf-Boot: Germany's cruel colonialism | DW | 05/16/2021. Accessed December 9, 2021 (German).

- ↑ Wolfgang Mulke: The restitution of colonial artifacts is making slow progress. In: www.goethe.de. Retrieved September 21, 2021 .

- ^ Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com): Namibia: Dispute over the return of the Witbooi Bible | DW | February 26, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com): Namibia receives Cape Cross column back | DW | May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019 .

- ↑ Provenance research on human remains . In: Wikipedia . April 9, 2019 ( Special: Permanent Link / 187401506 [accessed May 31, 2019]).

- ^ Linden Museum Stuttgart, Ed .: Linden Museum - Schwieriges Erbe. Retrieved May 23, 2019 .

- ^ Museum für Naturkunde Berlin: Cultural and social sciences of nature. April 9, 2019, accessed May 31, 2019 .

- ^ Ina Heumann, Holger Stoecker, Marco Tamborini and Mareike Vennen: Dinosaur fragments . Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen, July 26, 2018, accessed on May 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Key points for dealing with collection items from colonial contexts. Retrieved May 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Foreign Office: Foreign Office - Minister of State Müntefering on the key points for dealing with collections from colonial contexts. Retrieved May 27, 2019 .

- ↑ HEIDELBERGER OPINION | World Cultures Museum. Retrieved May 31, 2019 .

- ^ German Loss of Cultural Property Center - funding in the area of “Cultural Property of Colonial Contexts”. Retrieved May 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Guide to dealing with collection items from colonial contexts. In: Deutscher Museumsbund eV Retrieved on July 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Thomas E. Schmidt: Colonial art: A game for power. In: https://www.zeit.de/ . February 13, 2019, accessed December 9, 2021 .

- ^ Sophia Nätscher: "Colonial objects" in the Humboldt Forum and in the Musée du Quai Branly - an interdisciplinary debate . ( academia.edu [accessed November 26, 2021]).

- ^ Réunion des musées nationaux (ed.): Sculptures. Afrique, Asie, Océanie, Amériques . Paris 2000, ISBN 2-7118-4028-X , pp. 80 with numerous illus .

- ^ French Embassy in Berlin: President Macron in Ouagadougou: Development in Africa is a project between two continents. In: https://de.ambafrance.org . April 27, 2018, accessed December 21, 2021 .

- ^ Musée du quai Branly: Restitution of 26 works to the Republic of Benin. Accessed September 21, 2021 .

- ^ La France acte la restitution définitive d'objets d'art au Sénégal et au Bénin . In: Le Monde.fr . July 16, 2020 ( lemonde.fr [accessed July 17, 2020]).

- ↑ Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen: NMVW - Collections . In: collectie.wereldculturen.nl . Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Catherine Hickley: The Netherlands: Museums confront the country's colonial past. In: https://en.unesco.org . October 8, 2020, accessed November 30, 2021 .

- ↑ Catherine Hickley: Forging ahead with historic restitution plans, Dutch museums will launch € 4.5m project to develop a practical guide on colonial collections ( en ) In: www.theartnewspaper.com . March 10, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- ↑ a b Debate about the return of colonial art treasures. In: science.ORF.at, September 6, 2018 (accessed June 7, 2019) - Statements by Claudia Augustat, curator of the South America Department of the Weltmuseum.

- ↑ Weltmuseum curator on colonialism: “There are very big gaps”. In: Der Standard online, November 27, 2018 (accessed June 7, 2019) - Statements by Nadja Humberger, curator of the Africa Department of the Weltmuseum.

- ↑ a b Art return: #MeToo in the museum depot. In: Der Kurier online, May 22, 2018 (accessed June 7, 2019) - Statements by Sabine Haag , General Director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, to which the Weltmuseum belongs.

- ↑ Christoph Irrgeher: Giving is more difficult than receiving . Retrieved March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Savoy 2021, pp. 151-161

- ^ Bénédicte Savoy: Return of the Benin bronzes: A case of deportation . In: FAZ.NET . ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed December 13, 2021]).

- ^ National Museums in Berlin: Benin Dialogue Group specifies plans for museums in Nigeria. Retrieved November 25, 2021 .

- ↑ Lanre Bakare: Regional museums break ranks with UK government on return of Benin bronzes. In: http://www.theguardian.com . March 26, 2021, accessed November 25, 2021 .

- ↑ Nadia Khomami: Cambridge college to be first in UK to return looted Benin bronze. October 15, 2021, accessed November 26, 2021 .

- ^ Critical Changes. Pitt Rivers Museum, accessed November 25, 2021 .

- ↑ Kanishk Tharoor: Museums and looted art: the ethical dilemma of preserving world cultures. In: http://www.theguardian.com . The Guardian, June 29, 2015, accessed December 6, 2021 .

- ^ Catherine Hickley: Smithsonian Museum of African Art removes Benin bronzes from display and plans to repatriate them. In: https://www.msn.com . Accessed December 6, 2021 .

- ^ Smithsonian Magazine, Nora McGreevy: Why the Smithsonian's Museum of African Art Removed Its Benin Bronzes From View. Accessed December 6, 2021 .

- ^ Anna Codrea-Rado: African Officials Respond to France's Restitution Report. November 30, 2018, accessed May 10, 2019 .

- ^ Kwame Opoku: Coordination of African Positions on Restitution Matters. May 21, 2019, accessed May 23, 2019 .

- ^ National Museums in Berlin: Benin Dialogue Group specifies plans for museums in Nigeria. Retrieved August 2, 2019 .

- ↑ International Inventories Program: Explore the Database. In: https://www.inventoriesprogramme.org . Accessed December 22, 2021 .

- ↑ Annabelle Steffes-Halmer: Cologne exhibition about looted art from Kenya. In: https://www.dw.com . May 30, 2021, accessed on December 22, 2021 (German).

- ↑ Werner Bloch: Colonial looted art: "We don't want alms" . In: The time . December 31, 2018, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed June 2, 2019]).

- ↑ Quoted from Werner Bloch: Tanzania and the colonial era - The African view. Retrieved June 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Gloria Emeagwali: African Treasures - Kwame Opoku's Quest for Justice. In: https://www2.ccsu.edu . 2021, accessed December 20, 2021 .

- ↑ Kwame Opoku: Are we receiving the restitution we seek? In: https://www.modernghana.com . December 7, 2021, accessed December 20, 2021 .

literature

- Biro, Yaëlle: Fabriquer Le Regard. Marchands, Réseaux Et Objets d'Art Africains à l'Aube Du XXème Siècle . Dijon: Les Presses Du Réel, 2018, ISBN 978-2-84066-283-9 . ( PDF )

- Chambers, Iain; Alessandra de Angelis; Celeste Ianniciello; Mariangela Orabona; Michaela Quadraro (Ed.): The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History . Routledge, London 2016, ISBN 978-1-315-55410-5 ( taylorfrancis.com ).

- Hicks, Dan: The Brutish Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution . Pluto Press, London 2020, ISBN 978-0-7453-4622-9 .

- ICOM Germany, ICOM Austria, ICOM Switzerland (ed.): Ethical guidelines for museums. 2nd, revised edition of the German version. Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-9523484-5-1 . ( PDF ).

- Hauser-Schäublin, Brigitta; Lyndel V. Prott. (Ed.) Cultural property and contested ownership: the trafficking of artefacts and the quest for restitution . Routledge, London 2016 , ISBN 978-1-3172818-2-5 .

- Laely, Thomas; Meyer, Marc; Schwere, Raphael (Ed.): Museum cooperation between Africa and Europe: a new field for museum studies . Transcript Fountain Publishers, Bielefeld, Kampala 2018, ISBN 978-3-8376-4381-7 .

- Malefakis, Alexis; Strange things. The reception of African art as cultural appropriation. In: Yearbook of the State Museum of Ethnology, Munich 13 (2009): 615–641.

- Lyndel V. Prott (Ed.): Witnesses to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects . UNESCO, Paris 2009, ISBN 978-92-3104128-0 ( google.com ).

- Thomas Sandkühler , Angelika Epple , Jürgen Zimmerer (Eds.): History culture through restitution? An art historians dispute (= contributions to historical culture, vol. 40) . Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 2021, ISBN 978-3-412-51860-8 .

- Sarr, Felwine ; Bénédicte Savoy : Report on the restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle. The restitution of African cultural heritage. Toward a new relational ethics . Paris 2018, ISBN 978-2-84876-725-3 , pp. 240 ( restitutionreport2018.com [PDF]).

- Sarr, Felwine; Bénédicte Savoy: Give it back. About the restitution of African cultural assets . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-95757-763-4 , pp. 224 (abridged German version of the French original).

- Savoy, Bénédicte; Guichard, Charlotte; Howald, Christine (Ed.): Acquiring cultures: Histories of World Art on Western Markets . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Boston 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-054508-1 .

- Savoy, Bénédicte: Africa's Struggle for Its Art: History of a Post-Colonial Defeat . CH Beck, Munich 2021, ISBN 978-3-406-76696-1 .

- Savoy, Bénédicte with Robert Skwirblies and Isabelle Dolezalek: Prey: an anthology on art theft and cultural heritage . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-7518-0312-0 .

- Shylon, Folarin: The Recovery of Cultural Objects by African States through the UNESCO and UNIDROIT Conventions and the Role of Arbitration . In: Uniform Law Review - Revue de droit uniforme . No. 5 , 2000, doi : 10.1093 / ulr / 5.2.219 .

- Stamatoudi, Irini A .: Cultural property law and restitution: a commentary to international conventions and European Union law . Edward Elgar, Cheltenham 2011.

- Thurner, Ingrid: Art as a fetish. On the western reception of African objects. In: Communications from the Anthropological Society in Vienna. Vol. 127, 1997, ISSN 0373-5656 , pp. 79-97.