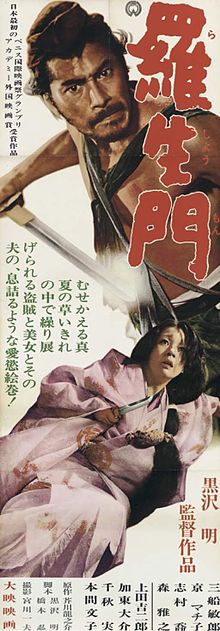

Rashomon - The Pleasure Grove

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | Rashomon - The Pleasure Grove |

| Original title | Rashomon |

| Country of production | Japan |

| original language | Japanese |

| Publishing year | 1950 |

| length | 88 minutes |

| Rod | |

| Director | Akira Kurosawa |

| script |

Shinobu Hashimoto , Akira Kurosawa |

| production | Daiei |

| music | Fumio Hayasaka |

| camera | Kazuo Miyagawa |

| cut | Akira Kurosawa |

| occupation | |

| |

Rashomon - Das Lustwäldchen ( Japanese 羅 生 門 , Rashōmon ) is a Japanese feature film from 1950. Akira Kurosawa , who also wrote the screenplay with Shinobu Hashimoto , directed the film based on two short stories ( Rashomon and In the Thicket ) by Akutagawa Ryūnosuke . The subtitle “Das Lustwäldchen” was added by the German distributor for moviegoers who can't do anything with Rashomon alone. He refers to "In the thicket".

The film is valued as a milestone in international film history and seen as the earliest successful connection between traditional Japanese motifs and European film art, but presents the plot exclusively from the point of view of the Japanese value system. Kurosawa developed these characteristics throughout his life, especially in the West well-known productions. Direction and acting were trend-setting for the later development of the genre. The plot of the film was often discussed in Western culture and the phenomenon illustrated in the film that a social action is perceived and remembered (completely) differently by different people is also called the Rashomon effect in the social sciences, law and philosophy Use. In addition, the film was shot shortly after the end of the Pacific War and thus also discussed as a proxy for questions of guilt , cause and truth in connection with serious crimes.

action

The plot has nothing to do with the rashōmon legend, but only uses it as a framework. The legend takes place in a mood of doom and end times , for which the ending Heian period stands in Japanese literature . The film is about the portrayal of the rape of a woman and the murder of her husband, a samurai .

The film consists of three completely separate levels: the framework story of the rashōmon, an action in front of a court and the main story, which is repeated four times in different versions during the film, each of the three involved in the incident tells a different version of the course of the crime; there is also the story of a passive witness, a woodcutter.

Framework level of action

Roles: monk, lumberjack and citizen

First, the framework is developed from the meeting of a monk , a woodcutter and an unspecified figure, a citizen , at a historical gate called Rashōmon, whereby the citizen can tell the other two levels of action (court hearing and main story). The events take place in the middle of the 12th century near the city of Kyōto , when the gate mentioned already shows significant earthquake damage and signs of decay and stands abandoned in the middle of the forest. The characters meet there during a heavy storm because they are looking for shelter and start talking to each other.

First, stories of stories are exchanged. In the later course of the film, after the other two levels of action are well developed, it turns out that the woodcutter has made his own observations, but he is reluctant to reveal them.

Action level in court

Roles: monk, lumberjack, bandit, woman, samurai in the form of the ghost woman and a policeman.

The trial is one of the two levels of action that the monk and lumberjack tell the citizen at the rashōmon. There is no difference of opinion about its course. During the trial, those involved in the crime (woman, samurai and bandit) appear and describe the course of events from their point of view in three completely different versions, each of which is stringent and logical, but contradicts the other two. The crime victim, the samurai, speaks in court through a medium ( miko ) from the afterlife.

The dish is strongly stylized and remains invisible to the viewer. The actors act head-on in front of the camera and address the viewer as if he were the judge himself. The judge's questions are asked by the actors. A stylistic device of Japanese theater art, word repetition, is successfully implemented on film for the first time.

Monk and lumberjack are present as witnesses. We learn that a police officer captured the robber when he fell from his horse. The lumberjack found the body. The fact that he is also a witness to the crime, he withheld in court, because he wants to have as little as possible to do with it. He claims to know the pure truth as a completely uninvolved person, but tells his version only later at the rashōmon at the urging of the citizen.

Main level of action

Roles: bandit, woman and samurai

The main plot takes place in an unspecified "forest of demons" on the road between Sekiyama and Yamashina . It is narrated by a total of four characters in four different versions , each version being shaped by subjective interests. The focus is not on guilt and innocence, but shame and honor: All three characters involved in the crime claim for themselves that they made the murder of the samurai possible through their behavior; the samurai claims to have killed himself. This reflects those Japanese moral concepts that lose face outweighs conviction for murder. The version of the woodcutter, on the other hand, leaves none of the three criminals a spark of honor. The dramatic final increase sheds new light on the whole thing.

Undisputed facts

The notorious bandit Tajōmaru lives in the forest of demons , who ambushes travelers and, on the day of the crime, meets the high-ranking samurai Takehiro, who is passing through with his horse and his young and beautiful wife Masako. The bandit lures the samurai into the undergrowth with the prospect of a good deal, overpowers and ties him up and rapes the woman in front of his eyes. After that, the samurai is stabbed to death, the woman escapes, and the bandit is arrested three days later. These very concrete facts are never questioned by any of the figures.

The bandit's version

The bandit Tajōmaru, who appears tied up in court, stated in view of his safe execution at the beginning that he does not want to excuse himself into lies and fully confess. He accuses himself of luring the samurai into the undergrowth, tying him up and raping the woman in front of her husband, giving herself to him after an initial knife fight. When Tajōmaru finally wants to leave the two of them alive, the woman suddenly begged him to duel with her husband, as she could only continue to live in honor if only one of the men survived. She wants to join the stronger and, if necessary, live as a robber bride, if only the outside world does not find out about the shame of rape. Tajomaru then unleashed the samurai and defeated it in an honorable sword fight for life and death according to traditional rules, which was respectful for both sides. However, the woman fled and he did not look for her.

Tajōmaru justifies his reprehensible acts with the fact that he is a criminal who lives from robbing others. As the reason for the rape, he gives the great physical attraction of the young woman and the joy that was associated with the humiliation of the samurai, who had to witness the act with his own eyes. Tajomaru considers his honor to be immaculate because he had led a fair sword fight with an open outcome, from which he finally emerged victorious. In doing so, he subsequently acquired the right to be victorious over the wife of the vanquished. He only accepts his imminent execution as a punishment for his way of life, but not for any moral misconduct in the course of the offense under negotiation.

The woman's version

The samurai's wife, Masako, delivers a completely different report: in order to save her husband, she gave herself to the bandit after the knife fight, who then disappeared. Her husband, who was saved in this way, had only contempt for her. He did not respond to her plea for forgiveness and the plea for redemption through killing, as tradition required. Masako claims to have passed out with her dagger in hand, and after she came to that she found her husband stabbed to death. She then tried to drown herself in a lake, but she did not succeed.

In this version, the woman found herself in a fateful victim role without any options of her own. After the hopeless knife fight against the bandit, she had no other option to save her husband than to surrender to the bandit. But that inevitably dishonored her. Her fate was definitely sealed by meeting the bandit.

The woman's statement is underlined by an adaptation of Ravel's Boléro composed by Hayazaka on behalf of Kurosawa , which is confusingly similar to this in all characteristic features.

The version of the samurai

The samurai Takehiro, who speaks in court through a medium from the afterlife, describes his dire situation and curses the bandit, but even more his wife Masako. She not only surrendered to the bandit, but also responded to his offer to join him as a robber bride. When both finally wanted to leave, Masako suddenly asked the bandit to kill her defenselessly bound husband, otherwise she would not be able to regain her outward honor . But even the bandit was appalled by this demand and deeply despised Masako for this betrayal. Finally Masako fled, the bandit unleashed the samurai and left him there. He himself committed suicide by stabbing his heart with a lady's dagger, crying.

This version only accuses the bandit of his violent lifestyle, but not of misconduct with regard to the classic Japanese code of honor . Rather, the samurai forgives the bandit because he did not tolerate the woman's betrayal of her husband and master, which is much more serious in Japanese culture. The samurai eventually gets his honor back, as he devalues himself for his failure and uses the only sure way to erase the shame of a lost sword fight with an outlaw. As a further honorable moment he did not hide his dishonor by killing his wife, which he was able to do because of the remote location of the place. He also did not choose the option of killing his wife as an adulteress instead of himself, which a liege would have been allowed to do in order to be able to continue living in full honor.

The lumberjack's version

The lumberjack appears on the court level as a witness initially only for the crime scene, but at the urging of the citizen admits in the framework action at the Rashōmon gate that he also observed the actual course of events. His narrative begins at the moment when the bandit Tajōmaru offers the woman treasures and an honest married life if she joins him. Masako, however, had refused to make their own decision about their fate and instead demanded a life-and-death sword fight between the two men; then she wants to stay with the winner. The three then reflected on the situation in short verbal fights, and both men, the samurai and the bandit, indicated that they did not want to fight each other; both would have disapproved of Masako's betrayal of her husband. The bandit is an "honest" robber and only wanted to rob the woman with force or cunning, but that she turned against her own husband in the end and gave him up to die, he finds abhorrent. Masako then received the request to commit suicide from her master, which she had to follow immediately according to the code of imperial Japan. However, Masako did not agree with this solution. With death before her eyes, she attacked her husband with a desperate speech and accused him of cowardice. Before he could demand death of his wife, he had to defeat the bandit himself. Masako, on the other hand, accused the bandit of not even wanting to fight for her, even though she was ready to share her life with him. A woman wants to be conquered with the sword.

According to the story of the woodcutter, a humiliating scuffle broke out, in the course of which the bandit only with great difficulty gained the upper hand and stabbed the defenseless samurai lying in the bushes with his sword. When the bandit asked for his reward, Masako ran away.

This version accuses all three participants of the most unworthy conduct. The samurai is called an incompetent coward who does not want to fight and instead orders his wife to commit suicide. She surrenders to a stranger, betrays her master and shortly afterwards demands his duties nonetheless. Finally, she also cheated the bandits out of the promised allegiance. Finally, the bandit took the woman by force, was not ready to fight and, like the samurai, did not obey fair rules of fight.

In order to save his honor from the outside world, the woodcutter does not mention that he is the thief of the dagger.

Dramatic climax

In the temple, the lumberjack, monk, and citizen's discussion of the lumberjack's report is interrupted by the cry of an infant. The three men find an abandoned baby in a basket, and the citizen steals a kimono and an amulet , both of which are intended for the baby. The woodcutter accuses the citizen of robbing an abandoned baby, but the citizen replies with the question of the whereabouts of the dagger. Since the woodcutter does not answer, the citizen accuses him of being a thief too. With a smug smile and a giggle, the citizen sees himself confirmed in his observations that all people selfishly only have their own interests in mind.

The monk is shaken in his belief in humanity. He lets himself change his mind, however, when the woodcutter takes the baby from his arms. He lets himself be softened when the woodcutter explains to him that he has six children at home and one more does not matter. This simple message, so to speak, compensates for the theft of the dagger. The monk hands the baby over to the woodcutter and assures him that he does not want to give up his belief in humanity. In the final shot, the woodcutter can be seen walking home with the baby in his arms, which is no longer crying. It has also stopped raining, the clouds have lifted and the sun emerge.

Importance of the film

Philosophical meaning

The film was discussed around the world mainly in terms of the existence of an objective truth.

The main themes of the film are the concepts of memory , truth and facticity . Questions the film raises are: Does the truth even exist ? Or just several very personal partial truths? The epistemological view that perceptions never provide an exact picture of reality is at the center. Each person in the film tells their own story, which is coherent in itself, but which leaves out facts that are visible in the other stories. The film also reflects the own, objectifying function of the film image: some testimonies that you see orally and that are initially credible are themselves only the visualization of the memories of other people who reproduce external testimony, of which they in turn witness became. What actually happened becomes more and more unfathomable through his increasing verbal commentary and the citation of the comments. It is precisely through this careful walk through the various subjective "truths" that it becomes clear what drives such subjective perception. Whoever understands this message has found a method to get closer to the actual truth, which is far more important than the correct recognition of the flat superficial events.

The Jewish religious philosopher Martin Buber wrote in a letter to Maurice Friedman in 1953: “Could you perhaps get me the book of the Japanese film Rasummon ? I saw it in Los Angeles, was deeply impressed by it and would like to use its essential content to illustrate something in an anthropological chapter. [...] It is quite important to me [...]. "

Psychological importance

The psychological meaning of the film lies in the fact that it shows how different interests and motives significantly influence the perception of a situation. From a psychological point of view, the existence of reality is not up for debate, but its reflection by direct and indirect observers, who form their own conceptual constructs from what is happening, become significant. The phenomenon is now sometimes referred to as the Rashomon effect , but in a scientifically elaborated form in other theories, for example, it is known as cognitive distortion or selective perception .

Film historical significance

The structure of the film on three levels, the careful elaboration of the characters, the extremely meticulous and detailed implementation and the high quality of the acting were very surprising at the time. Such high quality production from post-war Japan was not expected in the West. The film made Akira Kurosawa internationally known as a director and the actor Toshirō Mifune a world star. Embedded in the story of a search for truth, Kurosawa's narrative technique forces the viewer to distrust their own eyes. Kurosawa's formal innovations also influenced western cinema. For example, he recorded the famous walk of the woodcutter through the demon forest with several cameras at the same time and then assembled the settings to create an amazingly gliding image flow. Like later films by Kurosawa, however , Rashomon was underestimated and little known in Japan.

In 2003, the Federal Agency for Civic Education, in cooperation with numerous filmmakers, created a film canon for work in schools and included this film on their list. In 1964, Martin Ritt shot a not particularly successful western remake of the film under the title Carrasco, der Schänder (original title: "The Outrage") with Paul Newman in the role of the bandit, Laurence Harvey as the officer and William Shatner as the monk .

Awards

The film ran in 1951 in competition at the Venice Film Festival . There he was able to assert himself against Billy Wilder's Reporter of Satan and the Disney cartoon Alice in Wonderland , among others , and won the Golden Lion as the first Japanese film . Akira Kurosawa and Shinobu Hashimoto received a Blue Ribbon Award for Best Screenplay in 1951 . Machiko Kyō won for Rashomon and for her portrayal of Masako in Kozaburo Yoshimura's Itsuwareru seiso at the Mainichi film competition in the category Best Actress .

At the Academy Awards in 1952, the film received an honorary award for best foreign film . A year later, at the award ceremony in 1953, he was nominated in the category Best Production Design, which was won by the film City of Illusions . The film was nominated for the British Film Academy Award in 1953 for Best Film ("Best Film from any Source"), and the National Board of Review honored it in 1951 in the categories of Best Director and Best Foreign Film .

synchronization

The first German synchronization is based on an English translation and carries with it numerous translation errors as well as systematic changes and shows the typical deficiencies in emphasis and voice guidance at the time. The dialogues have been changed a lot in favor of lip-synchronicity. The film was often broadcast in the original sound with subtitles on German television late at night. There are many different sets of subtitles. Internationally, synchronization has mostly been avoided.

criticism

“A non-Christian document of religious depth. Worth seeing from 18. "

“Kurosawa's artfully chiseled action film about the relativity of truth opened the door to world cinema for Japan. Exciting, expressive, cinematic extraordinary and played brilliantly by Mifune with animalistic expression technique. (Highest rating: 4 stars = outstanding) "

“Perfectly composed pictures and a narrative technique with artistically mounted flashbacks give the story great tension despite its complexity. With »Rashomon« the Japanese film is accessible for the first time to a larger western audience, which reacts enthusiastically. "

literature

Books

- Akira Kurosawa, Donald Richie: Rashomon . Rutgers University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-8223-2519-2

- Blair Davis (Ed.), Robert Anderson (Ed.), Jan Walls (Ed.): Rashomon Effects: Kurosawa, Rashomon and their legacies . Routledge, 2015, ISBN 978-1-317-57463-7

- Parker Tyler: Rashomon as Modern Art . In: Julius Bellone (Ed.): Renaissance of the Film . Collier, London 1970, ISBN 0-02-012080-X .

- Leo Waltermann: Rashomon . In: Walter Hagemann (ed.): Film studies . tape 3 . Emsdetten 1954.

Book chapters and contributions to other works

- Akira Kurosawa: Something like an autobiography . Diogenes-Taschenbuch 21993, Zürich 1991, ISBN 3-257-21993-8 (original title: Gama-no-abura . Translated by Michael Bischoff [from the American], licensed edition by Schirmer / Mosel- Verlag, Munich 1985).

- Keiko Yamane: The Japanese cinema . History. Movies. Directors. In: Report Film, series of publications by the German Filmmuseum Frankfurt . Bucher , Munich / Lucerne 1985, ISBN 3-7658-0484-3 .

- Karsten Visarius: Rashomon . In: Peter W. Jansen , Wolfram Schütte (Ed.): Akira Kurosawa . Munich 1988.

- James Goodwin: Akira Kurosawa and Intertexual Cinema . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore / London 1993, ISBN 0-8018-4661-7 (English).

- Henry Hart: Rashomon . In: Lewis Jacobs (Ed.): Introduction to the Art of the Movies . Octagon, New York 1970, ISBN 0-374-94137-8 .

- David Howard, Edward Mabley: The Tools of Screenwriting . Saint Martin's Press, New York, NY 1993, ISBN 0-312-09405-1 (English).

- Siegfried Kracauer : Theory of the film . The salvation of external reality. In: Works . 1st edition. tape 3 . Suhrkamp , Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-07245-5 (Original title: Theory of Film . Translated by Friedrich Walter, Ruth Zellschan).

- Peter Wuss: The deep structure of the film artwork . Henschelverlag Art and Society , Berlin (East) 1986, ISBN 3-362-00018-5 .

- Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto: Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema . Duke University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-8223-2519-2 , pp. 182-190

items

- David Boyd: Rashomon - From Akutagawa to Kurosawa . In: Literature / Film Quarterly . No. 3 , 1987.

- Karl Korn : Rashomon, a Japanese film . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . May 6, 1953.

- Philipp Bühler: Rashomon . Federal Agency for Civic Education, Dossier - The Canon, April 14, 2010

- Keiko McDonald: Light and Darkness in Rashomon . In: Literature / Film Quarterly . No. 2 , 1982.

expenditure

- Rashomon Director: Akira Kurosawa [with Toshiro Mifune et al., Japan 1950, b / w film, 83 minutes, DVD & Blu-ray], trigon-film, Ennetbaden 2015, (restored version in HD, original with German subtitles and bonus film), FSK released from 16.

Web links

- Rashomon - The pleasure grove in theInternet Movie Database(English)

- Rashomon - The pleasure grove atRotten Tomatoes(English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Blair Davis, Robert Anderson, Jan Walls: Rashomon Effects: Kurosawa, Rashomon and their legacies . Routledge, 2015, ISBN 9781317574644 , p. 157

- ↑ Mario Bunge: Political Philosophy: Fact, Fiction, and Vision . Routledge, 2017, ISBN 9781351498814 , p. 286

- ↑ [1] and archived copy ( memento of the original from January 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Letter to Maurice Friedman dated January 3, 1953. in: Martin Buber: Correspondence from seven decades; Volume III. Heidelberg 1975, p. 325.