Japanese literature

Under Japanese literature ( Jap. 日本文学 Nihon Bungaku or Kokubungaku 国文学) refers to the in Japanese language written literature . It spans a period of around 1300 years, from Kojiki to the present, and it developed under various influences, such as that of China and Europe .

Japanese literature has a multitude of its own forms and specific themes that go hand in hand with the history of ideas and culture. For example, there was and is a distinct, if not always continuous, tradition of influential women who write. Also unique in world literature is the special form of atomic bomb literature (原 爆 文学, Gembaku Bungaku ), which thematically deals with the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki .

Definition and structure

There is no fixed, i.e. normative, definition of Japanese literature. In order to describe what can be understood as Japanese literature, it is helpful to begin with two basic considerations. On the one hand, it is important to consider the perspective, that is, the point of view from which one looks at Japanese literature. An academic understanding of Japanese literature in German or European Japanology, as primarily meant here, looks different than the understanding of Japanese science Kokubungaku (国 文学). On the other hand, in order to delimit the subject area, i.e. what the term Japanese literature includes, it is important to make sure of the individual terms literature and Japanese .

In Europe, literature , derived from the Latin word litterae, was understood as learning and thus as everything that was written. In Germany, this view changed in the 18th century. In the Enlightenment and the Weimar Classic , an aesthetic claim was then attached to the concept of literature. Romanticism also added the term poetry to this literary term . During this time, the division into the three major genres also fell: poetry, epic and drama, which was supplemented by the genre of useful texts in the last century.

The Japanese word for literature, bungaku (文学) has seen a similar change in meaning, but with a different course over time. In Japan, it is the Meiji Restoration, often described as a decisive turning point, and the beginning of the Meiji period in which the change in meaning took place. Here, too, it was a matter of a shift in meaning from erudition to an understanding of literature as an area of art that was primarily committed to the aesthetic use of language as an object and medium. This development was preceded by the emergence of the "National School" ( Kokugaku ) in the Edo period . Expression of such an understanding of literature in the Edo period was about the term "bunbu ryōdō" (文武 両 道), which denoted the "two paths of learning and the art of war". In the course of the social and political changes at the beginning of the Meiji period, the medium of literature, the language, was understood as the national language ( kokugo ) and the concept of literature was consequently narrowed down to national literature ( kokubungaku ). Japanese literature in the Chinese language and tradition, as it was considered the epitome of erudition in the Edo period, was no longer a primary component of Japanese national literature with this paradigm shift. As in Germany over 100 years earlier, the division into genres came into use in Japan. Based on a high aesthetic value, however delimited, a distinction was made in Japan between so-called pure literature (純 文学, jun bungaku ) and popular entertainment literature (通俗 文学, tsūzoku bungaku ). The adjective Japanese was narrowed to Japanese in this context. Texts from the Ainu and from Ryūkyū were just as little a subject of Japanese literature as the popular and oral literary tradition.

If one looks at the definitions of the term kokubungaku in Japanese lexicons today , the term Japanese national literature, understood as part of a world literature, mostly includes the texts written by Japanese in Japanese and published in Japan, primarily pure literature. At the same time, the science (学問, gakumon ) that deals with this subject is integrated into the definition of Japanese literature and thus placed alongside it on an equal footing. In this sense, one can speak of a narrower understanding of Japanese literature, which at the same time corresponds more to a Japanese perspective.

In practice, however, it turns out that the boundaries are not drawn as sharply as a narrow definition would lead one to believe. The reasons for this can be different, for example of a systematic nature. The genre of drama, as we know it in Europe, cannot easily be applied to Japanese theater plays and text production. With Kabuki , Nō and Jōruri, for example, forms of expression have developed for which there is hardly any counterpart in Europe up to the present and which must be recognized as independent dramatic forms of expression. The differentiation between mass literature and pure literature in Japan, which corresponds to the dichotomy of trivial literature and canonical high literature in Germany and which is not congruent, is, for example, somewhat undermined by the fact that popular literature is also part of literary history.

On this basis, a broader understanding of Japanese literature includes works authored and published by Japanese in other countries and languages, as well as Japanese-language literature by non-Japanese. After that, Ainu texts would again be part of Japanese literature, as would works by the writer Yōko Tawada, who lives in Germany and writes in German, or the Korean-born author Miri Yū . The enormous number of Japanese literary magazines and new literary forms, such as the collaborative writing of mobile phone novels, can also be recorded as Japanese literature in this way. This broad conception corresponds more to the complicated system that "Japanese literature" presents itself with its many independent sub-areas and that invites you to address the perspective of Japanese literature.

Literary history

A literary historiography emerged in Japan at the end of the 19th century. The first literary history of Sanji Mikami and Kuwasaburō Takatsu, the "Nihon Bungakushi" (日本 文学 史), dates back to 1890. In this work, which dealt with literature up to the end of the Edo period, literary criticism and literary history are still mixed. Only the literary history of Juntarō Iwaki, the "Meiji Bungakushi" (明治 文学 史), published in 1906, is to be regarded as a classical literary history. The academic branch of literary studies, which goes back to the Kokugaku, and which felt obliged to positivism , concentrated literary historiography on author studies (作家 論, sakkaron ) and on the interpretation of works (作品 論, sakuhinron ). The only literary history that was complete and written in German up to its publication in 1906 is the "History of Japanese Literature" by Karl Florenz . In addition, in Germany, Florence was the first to hold a chair for Japanese Studies at the University of Hamburg.

Periodization

In general, when dividing literary epochs, it is customary to orientate oneself to history and thus to decisive political and social changes. In addition to such a division, the adoption of reigns as a scheme is also common in Japan. On the basis of political history, the following classification has become established:

- Antiquity (approx. 600–794)

- Classical, Heian period (794–1185)

- Middle Ages (1185–1600)

- Early modern period (1600–1868)

- Modern (1868–1945)

- Contemporary literature (1945-today)

antiquity

The first evidence of Japanese written culture was not yet literature, but engraved characters on bronze swords from the 6th century that were found in Kofun graves.

From the 7th century, Korean monks brought Chinese scriptures to Japan. The nobility and civil servants learned the Chinese language both spoken and written and soon began to write their own works. Initially, Chinese served as the written language . Soon, however, the Chinese script was also used to write Japanese texts. However, as the structure of the Japanese language differs completely from the Chinese language, the script was adapted in several steps.

The two oldest partially preserved Japanese classics are Kojiki and Nihonshoki from the 8th century, written mythologies that depict Japanese history based on the model of Chinese historical classics . In addition to prose texts, these also contained short poems.

Characteristic of the literature of the Asuka and Nara periods was the lyrical poem: In addition to the Kanshi , poems in the Chinese language, a second art form developed, the Waka - Japanese poetry. From the older informal short poems in Kojiki, solid forms in lines of five or seven syllables developed. The most important are Chōka (long poems), which consist alternately of five or seven syllables per verse and are concluded by a seven-silvery verse, and Tanka (short poems), which consist of five verses with 31 syllables, the syllables on the Stanzas are distributed in the form 5-7-5-7-7. While the male officials mainly wrote kanshi, the waka were the domain of the ladies-in-waiting.

The most important volume of poetry of this time was the Man'yōshū , a collection of poetry collections - including the Kokashu and Ruijō Karin . It was compiled around 760, and the oldest poems can be dated back to the 4th century. Ōtomo no Yakamochi and Kakinomoto no Hitomaro are important authors of the work. The Man'yōshū is written in the so-called Manyōgana script. Chinese characters were used in their phonetic reading ( on-reading ) to represent the inflected forms of Japanese grammar . Hiragana and Katakana , the Japanese syllabary scripts, developed from the Manyōgana in the Heian period . For a long time, hiragana was primarily used by noble women.

After the kanshi was in vogue in the short period of the 9th century, the waka returned to the interest of the court nobility. Emperor Uda and his son, Emperor Daigo , took an interest in waka. At the emperor's decree, court poets created an anthology of waka, the kokinshu . One of the editors, Ki no Tsurayuki , wrote the preface in Kana . At the end of the Heian period , a new form of poetry called Imayo (modern form) was developed. A Ryojinhisho collection was edited by Emperor Go-Shirakawa .

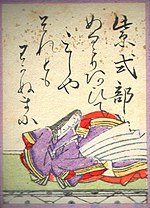

At that time the development of prose began. Ki no Tsurayuki wrote the Tosa Nikki , a travelogue in Cana, in which he expressed his grief over the death of his daughter. At the beginning of the 11th century lived the two most important writers of the era: Sei Shōnagon , author of the pillow book ( makura no soshi ) and Murasaki Shikibu , who probably wrote the Genji Monogatari . The Genji Monogatari or "The Story of Prince Genji" is considered the first psychological and oldest novel in the world that is still preserved today.

middle age

The ex-emperor Go-Toba arranged for a collection of wakas, the Shinkokinshu . This was the eighth imperial waka collection. She is considered to be one of the best in the genre.

The war at the end of the 12th century was depicted in Heike Monogatari (circa 1371), an epic depicting the dispute between the samurai clans Minamoto and Taira .

Other important works were Hōjōki (1212) Kamo no Chōmeis and Tsurezuregusa (1331) Yoshida Kenkōs .

In these works the Japanese writing system was established, in which the two types of letters kana and kanji are mixed. The literary works of this period dealt with the view of life and death, a simple lifestyle, and the redemption of the dead.

The form of the Rengas originated in poetry . In the Muromachi period , the renga became the main form of poetry. At the same time, the Noh Theater also reached its climax thanks to the work of Zeami Motokiyo .

The renga was the Japanese love poem. It came from Waka in the imperial court in antiquity and developed at the court of the two emperors and the samurais in the Middle Ages. It reached its peak in the 14th century. A collection of Renga Tsukubashu ( Tsukubas Collection) was compiled and then the subordinate category of the imperially selected collection Why Kokinshu in antiquity. Renga was actually the collaborated waka, therefore as short as waka with 31 syllables in two punches, but you could make it arbitrarily long according to rules. During this time, one often wrote longer Renga works, for example with 50 or 100 punches. Important rena poets were Nijō Yoshimoto , Io Sogi and Ichijo Furuyoshi in the Muromachi period and Satomura Joha in the Sengoku period .

Citizens also wrote Renga in the Middle Ages, and a new tendency developed. They were called Haikai-no-Renga , literally “parodistic Renga”, the motifs of which were found in bourgeois life.

Early modern period (Edo period)

The literature of the Edo period is characterized by developments in literature in three areas: novel, poem and drama.

Three major writers appeared in the Genroku period: Ihara Saikaku , Matsuo Bashō, and Chikamatsu Monzaemon . Saikaku wrote several novels, the subjects of which he found in daily life. Basho renewed the Haikai-no-Renga tradition and became a master at it. During this time, most poets preferred the Renga with 36 punches, which subsequently became the standard. Chikamatsu wrote plays for the joruri , a type of puppet theater. He drew his themes from the past and present.

Chinese literature and philosophy were still at the core of male scholar education. Many Japanese sinologists have therefore written in Chinese. Important poets in this area were Rai San'yō and Hirota Senso .

In the middle of the Edo period, however, interest in classical Japanese literature and the way of thinking reappeared. The research then carried out is known as Kokugaku (national teaching ). The ancient works like Kojiki , Man'yōshū or Genji Monogatari were part of the research. The ancient Japanese language (only written in Kanji ) had almost been forgotten by this time. Therefore, research into Ancient Japanese and Classical Mindset was first necessary to understand the works.

Modern (1868–1945)

Meiji period literature

Enlightenment and the essence of the novel

With the dawn of the Meiji period (1886–1912), the Age of Enlightenment (啓蒙 時代, Kamō Jidai ) began, in which Western civilization was adopted and focused on the translation of literature and Western ideas. In this context, Japanese scholars created a considerable number of new words (neologisms) to translate foreign scriptures into Japanese. These included Yukichi Fukuzawa's Gakumon no susume (1872), Masanao Nakamura's Saigoku risshihen (1871) and Chōmin Nakaes Contract Sociale ( Shakai keiyakuron , 1882). Arinori Mori , founder of the Meirokusha Association , advocated freedom of religion and equal rights for women. With reference to the difficulties that the translation of foreign works caused due to the lack of vocabulary, he even pleaded for the Japanese language to be replaced in favor of English.

With the beginning of the Meiji era, the literature of the Edo period did not come to an abrupt standstill, but rather it mingled from the Meiji Restoration (1885) to the publication of the first literary theoretical treatise On the essence of the novel by Shōyō Tsubouchi and remains next to it consist. In the late Edo period, Gesaku - and translation literature as well as the political novel (政治 小説, seiji shōsetsu ) determined literary life. Kanagaki Robun met the cultural innovators and enlighteners with humorous novels Seiyō dōchū hizakurige (1870) and with Aguranbe (1871).

The translations of Western European literature spread rapidly as translation literature between 1877 and 1886. Representative translations were about Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days (1887) translated by Kawashima Jūnosuke or Shakespeare's drama Julius Caesar translated by Shōyō Tsubouchi as (1884). The founding of the Liberal Party (自由 党, Jiyūto ), the Constitutional Progress Party (改進 党, Rikken Kaishinto ) and the parliament , which met for the first time (1890), as well as the Freedom and People's Rights Movement (自由民 権 運動, Jiyū Minken Undō ) were formed by 1877 to 1886 the themes of the political novel. The two bestsellers Keikoku Bidan (経 国 美談, 1884) by Ryūkei Yano and Kajin no kigū (佳人 之 奇遇, 1885) by Sanshi Tōkai , which propagate political ideas and opinions, fascinated a large number of readers. After the publication of Tsubouchi's romantic theoretical work The Essence of the Novel, the focus was on a realistic representation. Tetchō Saehiro's novel Setchūbai (雪中 梅, 1886) is an example of this realistic writing style .

Realism and romance

The modern age of Japanese literature essentially began with Tsubouchi's literary theoretical work Das Wesen des Romans (小説 神 髄, Shōsetsu Shinzui ) from 1885 and with the critical essay Remarks on the Novel (小説 総 論, Shōsetsu Sōron ) written by Futabatei Shimei in 1886. The Gesaku literature was overcome and Shimei 1887 published novel Ukigumo (浮雲) marked the beginning of the modern novel in Japan.

In this way, on the one hand, the realistic contemporary novel began to take hold, on the other hand, nationalism also increased. There was a re-evaluation of classical Japanese literature, for example by Ihara Saikaku and Chikamatsu Monzaemon . In 1885, Ozaki Kōyō , Yamada Bimyō and others founded the literary society Kenyūsha and published the first avant-garde magazine Garakuta Bunko (我 楽 多 文庫). The publication of Kōyō's works Ninin Bikuni iro zange (二人 比丘尼 色 懺悔, 1889) and Konjikiyasha (1897) heralded the beginning of neoclassicism (新 古典 主義, shinkoten shugi ). Kōda Rohan's criticism and interpretation of classical literature, as well as his novels Tsuyu dandan , Fūryūbutsu (both 1889) and Gōjū no tō (1891) had a great impact on the literary world.

Modernization progressed, people's self-confidence sprouted, and romanticism entered the literary stage with the undisguised demand for individual freedom. In 1890 Mori Ōgai's short story “The Dancer” ( Maihime ) was published, which deals with his experiences in Germany and describes the liberation of the self. He also translated Hans Christian Andersen's autobiographical novel The Improvisator , a love story rich in poetic mood and imitating the classical style, into Japanese in 1892. Kitamura Tōkoku committed suicide at the age of 25 after he had written his criticism Naibu seimeiron in 1893 , thus emphasizing the completeness of the soul of the modern self. Higuchi Ichiyō died at the age of 24 after her two major works Takekurabe and Nigorie (both 1895) had received great attention. Izumi Kyōka opened up the world of the fantastic and mysterious with his works Kōya hijiri (1900), Uta andon (1910), which are representative of Japanese romanticism. Kunikida Doppo published Musashino in 1898 , in which he portrayed the beauty of nature in a miscellular manner, and a year later, in 1899, Tokutomi Roka , an advocate of the Christian faith, published his novel Hototogisu, with which he cast a look at society. A little later, Doppo turned away from romanticism and naturalism (自然 主義). The Japanese Romanticism had a relatively short existence compared to the European one, as it were as a transitional stage in the history of ideas.

Naturalism, Natsume Sōseki and Mori Ōgai

With the end of the Meiji period and the beginning of the 20th century, Japanese naturalism (自然 主義, Shizenshugi ) emerged under the influence of the works of Émile Zola and Guy de Maupassant . While European naturalism, shaped by the theory of heredity, endeavored to achieve a realistic representation of the milieu, Japanese realism turned to the exposure and revelation of naked reality. Beginning with Shimazaki Tōsons novel Hakai ("Outcast", 1906), the direction of Japanese naturalism decided with Tayama Katai's novel Futon (1907). Katai's novel was the starting point of the Japanese "first-person novel" ( Shishōsetsu ), which was to shape the future of the Japanese novel.

At the same time as the first- person novel, a mainstream of Japanese literature, a large number of counter-movements developed (反 自然 主義 文学, Hanshizenshugi bungaku ). The counter-movements include Natsume Sōseki , Mori Ōgai , Aestheticism (耽美 主義, Tambishugi ) and the literary group “White Birch” (白樺 派, Shirakabe-ha ). Sōseki and Ōgai represent their own countercurrent: which is referred to as “description of nature” (余裕 派, Yoyūha ) and “Parnasse” (高 踏 派, Kōtōha ). Sōseki, who wrote descriptions of nature and haiku at the beginning , entered the literary stage with “ Ich der Kater ” ( Wagahai wa neko de aru ) in 1905. Examples of works with which he deviates from the literary style of naturalism are “Botchan” and “Kusamakura” (both 1906). In the first part of his trilogy "Sanshirō" (1908), "Sorekara" (1909) and "Mon" (1910) he described the mental state of a contemporary intellectual. Also Ōgai turned after the resumption of his writing activity and after the novels "Seinen" (1910) and "Gan" (1911), with "Shibue Chūsai" (渋 江 抽 斎) from naturalism and the historical novel (歴 史 小説, Rekishi shōsetsu ) to.

In addition, the representatives of the "Kiseki" movement (奇蹟 派): Hirotsu Kazuo , Kasai Zenzō and Uno Kōji (1891–1961) are to be counted among the authors of the Japanese first-person novels. They described the dark side of humans by exposing the “real” inner workings of the protagonists.

Poetry and drama from the Meiji period

In 1882, Yamada Masakazu (1848–1900), Yatabe Ryōkichi and Inoue Tetsujirō published an anthology of "New Style Poetry" (新 体 詩 抄, Shintai Shishō ). The new style poems in this first anthology of its kind were influenced by European poetry. Had poem (詩) have typically been as Kanshi understood, it began a varied between five and seven syllables Matrum to use. In this context, the anthology Omokage (新 体 詩 抄) by Mori Ōgai, who had returned from Germany, appears in 1889 , which is called the "high point of translated poetry", among others. Poems of Goethe included. In the same year, the collection of poems Soshū no shi (楚 囚 之 詩, about "Poems of a Prisoner") by Kitamura Tōkoku , which deal with the inner conflicts of the lyrical self after the failure of the civil rights movement, was published. In 1897 the collection of poems Wakanashū (若 菜 集) by Shimazaki Tōson, who worked on Kitamura's magazine Bungakukai (文学界), and two years later, in 1899, the anthology Tenchi ujō (天地 有情) by Doi Bansui , which are attributed to Japanese Romanticism.

In the poetry of symbolism, Kitahara Hakushū and Miki Rofū joined Kambara Ariake and Susukida Kyūkin . This period of poetry at the end of the Meiji period is also called Shiratsuyu no jidai (白露 の 時代, roughly "time of the (white) dew") in Japan . The anthology Kaichō on translated poems by Ueda Bin , which is important for Japanese symbolism, is worth mentioning , the meaning of which was only recognized after Bin's death in the Taishō period. The Japanese poetry forms tanka and haiku also found their way into Japanese romanticism. The activities of the Yosano couple should be mentioned in connection with the tanka. In 1900 the poetry magazine Myōjō by Yosano Tekkan appears for the first time , while his wife Yosano Akiko published her first collection of poems Midaregami (み だ れ 髪) a year later . This group also includes the poets Kubota Utsubo and Ishikawa Takuboku with his two collections of poetry Ichiaku no suna (一 握 の 砂, for example "A handful of sand", 1910) and Kanashiki Gangu (悲 し き 玩具, dt. "Sad toys"), which appeared posthumously in 1912 to count. Ishikawa turned to naturalism in later years, as did the writers Wakayama Bokusui with Besturi (別離, about "Farewell", 1910) and Toki Zenmaro with Nakiwarai from the same year. Sasaki Nobutsuna , who founded the group of poets Chikuhaku Kai (竹柏 会), published the magazine Kokoro no Hana (心 の 花) from 1898 . Masaoka Shiki published Utayomi ni atauru sho (歌 よ み に 与 ふ る 書, "writing dedicated to poets") in 1898 and founded the Negishi Tanka community , in which Itō Sachio and Nagatsuka Takashi also participated. Kitahara and Yoshii Isamu founded the group Pan no kai in 1908 , in which poems attributable to aestheticism were written.

Naturalism also had an impact on the theater. In 1906, Tsubouchi Shōyō and Shimamura Hōgetsu , who had studied in England and Germany from 1902 to 1905, formed the Bungei Kyōkai (文 芸 協会, for example "Society for Show Arts"), which, with performances such as Ibsen's Nora or A Puppenheim, was the starting point for Shingeki , "New Theater" should be in Japan. After the dissolution of the Bungei Kyōkai in 1913, Hōgetsu and Matsui Sumako joined the theater company Geijutsuza (芸 術 座) and performed plays by Tolstoy , with Resurrection enjoying great popularity. In addition, Osanai Kaoru and Ichikawa Sadanji II were active during this time . With nine performances from 1909 to 1919 they founded the movement "Free Theater" (自由 劇場, Jiyū Gekijō ).

Taishō period literature

Countermovements to Naturalism

Nagai Kafū , who had devoted himself to Japanese naturalism at the beginning, published his "Furansu Monogatari" ( French stories ) after his return from Europe in 1909 . This was followed in 1910 by Tanizaki Jun'ichirō's short story "Shisei" (し せ い, the tattoo ) and in 1924 "Chijin no ai" ( Naomi or an insatiable love ), with which aestheticism was born. At the center of this literary movement were the two literary magazines “Subaru” (ス バ ル, Pleiades ) and “Mita Bungaku” (三 田 文學), the literary magazine of the Keiō University . Other representative representatives of aestheticism were Satō Haruo (1892–1964) and Kubota Mantarō .

In contrast to aestheticism, the current “White Birch” ( Shirakabaha ) with its literary magazine of the same name concentrated on a humanism based on freedom and democracy . Significant works of this group were: "Omedetaki hito" (1911) and "Yūjō" (1919) by Mushanokōji Saneatsu , "Wakai" and "Ki no saki nite" (both 1917) by Shiga Naoya , "Aru onna" (1919) by Arishima Takeo and "Tajōbusshin" (1922) by Satomi Ton . In particular, Shiga Naoya's "first-person novel" and "emotional novel" (心境 小説, Shinkyō Bungaku ) exerted great influence on the young writers of his time as the literary norm of the so-called "pure literature" (純 文学, Junbungaku ).

In the middle of the Taishō period (1912-1926) began Akutagawa Ryūnosuke and Kume Masao , influenced by Sōseki and Ōgai and the from the literary magazine "Shinshijō" (新 思潮) of the University of Tokyo outgoing "New Realism" (新 現 実 der , Shin genjitsu shugi ) their literary activity. Akutagawa entered the literary stage in 1916 with “Hana” ( nose ) and soon became the favorite child of literary circles with his stories rich in classical subjects. In addition, Kikuchi Kan, known as a stage poet, wrote historical and entertainment novels, and Yamamoto Yūzō (1887–1974) wrote educational novels . Akutagawa died by suicide in 1927 after writing his two masterpieces "Kappa" and "Haguruma" ( cogwheels ). Akutagawa's suicide was viewed as a sign of the uncertainty of the times and shocked intellectuals and writers alike. Against Tanizaki, to whom narrative literature was important, Akutagawa defended literature against “ L'art pour l'art ”, a literature for its own sake, and the position that despite the charm of the (novel) plot, the novel has no value own what led to a literary controversy immediately after his death.

The rise of the entertainment novel

The rise of the entertainment novel began, starting from Ozaki Kōyō moral novel "Konjikiyasha", Murakami Namiroku (1865-1944) and Tsukahara Jūshien (1848-1917) historical novels ("Magemono") and Oshikawa Shunrōs (1876-1914) adventure novels, Time. In 1913, Nakazato Kaizan (1885-1944) began his historical novel " Dai-bosatsu tōge " to publish as a serial . This novel, which portrayed human fates, is considered the beginning of the entertainment novel. From 1925 onwards the magazine “King” appeared for the first time, in which all writers of entertainment literature at the time published. With the beginning of the Shōwa period, the works of Yoshikawa Eiji enjoyed great popularity. His novels "Naruto hichō" (鳴 門 秘 帖, 1933) and "Musashi" (宮本 武 蔵, Miyamoto Musashi , 1939), which are widely read to this day , earned him the reputation of a bourgeois writer. In addition, Osaragi Jirō and Shirai Kyōji (1889-1980) were important for the development of the popular historical novel.

The detective novel (探 偵 小説, Tantei Shōsetsu ), which came to Japan through the adapted novels Kuroiwa Ruikōs (1862–1920), was very much influenced by the prolific Edogawa Rampo , who wrote “Nisendōka” (二 銭 銅 貨) in 1923 in the magazine “ Shinseinen “(新 青年) made his debut, influenced. Forerunners of the detective novels were already by Koga Saburo and Yokomizo Seishi (1902-1981) and others. as historical novels were written, which were known in the Edo period as crime stories, so-called Torimonochō (捕 物 帳).

Pre-war literature of the Shōwa period

The modern and the proletarian literature

From around the mid-1920s to 1935, the literary currents of the modern age and proletarian literature stood side by side. The techniques of Dadaism , Futurism and Expressionism , which emerged in Europe after the First World War , were also adopted by Japan and from then on Japanese writers gave up monotonous realism and L'art pour l'art art. Nonetheless, Japanese Dadaism and Futurism remain eclectic and far removed from their European counterparts. By criticizing the established literary circles and the individualism of literary realism, Yokomitsu Riichi and Kawabata Yasunari began "neo-sensualism" (新 感 覚 派, Shinkankakuha ), which is thematically shaped by dreamlike, remote worlds and traditional sense of beauty. Yokomitsu's work “Fly” (蝿, Hae , 1923) was viewed under the influence of cinematic methods and in his “Essay on the Pure Novel” (純 粋 小説 論, Junsui Shōsetsuron , 1935) he tried the necessity of a “self-contemplating self” (自 分 を 見 る 自 分) as the fourth instance, in which relentless introspection is linked to self-confidence. In 1935 Kawabata began to write "Yukiguni" (Eng. Snow Country ), in which his understanding of aesthetics was perfectly expressed. Kawabata's understanding of aesthetics, which makes melancholy in the face of the transience of things ( mono no aware ) the basic attitude, is also the determining theme in “Matsugo no manako” (末期 の 眼, 1933).

The writers of the "Shinkō Geijutsuha" (新興 芸 術 派, the Neorealistic School ) formed a further current of that time, who turned away from purely autobiographical writing as a literary tributary and tried to exaggerate reality in writing in conscious opposition to proletarian literature. Kajii Motojirō's short story "Remon" (檸檬) from 1925, which was in the tradition of the first- person novel ( Shishōsetsu ) and Ibuse Masuji's short novel "Salamander" (山椒 魚, Sanshōuo , 1929), in which he caricatured the left as a caricature, are representatives to call this direction.

Hori Tatsuo and Itō Sei (1905–1969) solved neo-realism with a new psychologism (新 心理 主義, "Shishinri shugi"). Oriented towards psychoanalysis and influenced by Joyce and Proust, the state of mind moved into the focus of the writing. The techniques of stream of consciousness and the inner monologue were used for this purpose . During this time Kobayashi Hideo entered the literary stage with "Samazama naru ishō" (1929) and established the style of modern literary criticism.

Against the background of the political situation, the 1921 version of Komaki Ōmi et al. published magazine " Tanemakuhito ", with which the proletarian literature was brought to life. This current developed in an atmosphere of militarism that has prevailed since the Mukden incident . A large number of works were created, such as Kobayashi Takiji's "Kanikōsen" (蟹 工 船, 1929), Tokunaga Sunao's "Road without Sun" (1929) as well as works by Miyamoto Yuriko , Hayama Yoshiki , Nakano Shigeharu , Sata Ineko and Tsuboi Sakae (1899-1967) . In addition, the lively discussion of proletarian literature had an impact on the literary criticism of intellectuals such as Kurahara Korehito (1902–1999) and Miyamoto Kenji (1908–2007).

Contemporary literature (1945-today)

Post-war literature of the Shōwa period

For a Japanese classification of post-war literature and its problematization, see also: Japanese post-war literature

After the end of the war, writers such as Dazai Osamu , Sakaguchi Ango , Ishikawa Jun and others began the work of the “Buraiha” (無 頼 派, about School of Decadence ). In particular, the works "Shayō" (斜陽, 1947, dt. The sinking sun ) by Dazai, who committed suicide only a year later, and "Darakuron" (堕落 論, 1946, about: Essay of Degeneration ) by Sakaguchi were taken by the readers of the post-war period. Dazai's works, including the novel Drawn , quickly advanced to become classics of contemporary literature.

Nakano Shigeharu and Miyamoto Yuriko , who emerged from proletarian literature , founded the New Japan Literary Society (新 日本 文学 会) in 1945, founded the literary movement for “democratic literature” (民主主義 文学) and discovered the potential of workers' literature .

Also in 1945 the literary magazine "Kindai Bungaku" (近代 文学, Modern Literature ) was founded, in whose environment writers such as Takeda Taijun (1912-1976), Haniya Yutaka , Noma Hiroshi , Katō Shūichi , Ōoka Shōhei , Mishima Yukio , Abe Kōbō and Yasushi Inoue were active. The theme of Ōoka Shōhei's works are the experiences of war and American captivity as in “Furyoki” (俘虜 記, for example: diary of a prisoner of war ) and “Fire in the Grasslands” (野火, Nobi ), which were highly valued. In 1949 Mishima's novel “Confession of a Mask” was written, and in 1956 “The Temple Fire”. In 1949 Kawabata's romance novel “A Thousand Cranes” appeared, and in 1954 “A Cherry Tree in Winter”, both of which had an outstanding position in literary circles.

The post-war literature, represented by the first and second generation of post-war poets , was continued by Yasuoka Shōtarō , Yoshiyuki Junnosuke (1924–1994), Endō Shūsaku , Kojima Nobuo , Shōno Junzō , Agawa Hiroyuki , who formed a third generation. In 1955 Shintarō Ishihara work “Taiyō no kisetsu” (太陽 の 季節, 1955, sunny season ) appears as the first post-war manifesto . The Akutagawa Prize is developing into the most famous and important literary prize.

Women's literature also flourished again with writers such as Nogami Yaeko , Uno Chiyo , Hayashi Fumiko , Sata Ineko , Kōda Aya , Enchi Fumiko , Hirabayashi Taiko , Setouchi Jakuchō (* 1922), Tanabe Seiko (1928-2019) and Sawako Ariyoshi . In addition, the pioneer Kim Tal-su and in his successor Kin Sekihan and Ri Kaisei produced literature for the Korean minority in Japan .

Atomic bomb literature

The so-called “atomic bomb literature” (原 爆 文学, Genbaku bungaku ) can be viewed as a special feature of post-war literature, as well as Japanese literature in general . It was carried by authors who dealt thematically with the effects of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The atomic bomb literature in Japanese society itself has an ambivalent character. The need of the writers to give literary expression to the scope and the incomprehensible extent of the events, the experiences and the suffering of the Hibakusha was opposed by the censorship of the American occupiers until 1952 and the silence of society. The type of processing can be divided into three forms based on the writer. In works by writers who witnessed the drops themselves. These include Ōta Yōko , Hara Tamiki , Tōge Sankichi , Shinoe Shoda , the doctor Nagai Takashi , Sata Ineko , Fukuda Sumako , Inoue Mitsuharu , Hayashi Kyōko and Kurihara Sadako . The authors of this group describe their experiences mostly in a mixture of seemingly documentary descriptions and their own perception ( autodiegetic according to Genette ) Immediately after the surrender and the invasion of the American troops in Tokyo, the "Press Code" came into force in September 1945. One of the first impressive literary testimonies is Yoko Ota's article Kaitei no yona hikari , which could still appear in the Asahi Shimbun . Her novel Shikabane no machi (for example "City of Corpses"), which she wrote in autumn 1945, could only be published in an abridged version in 1948 and in full, then in 1950. In addition, Tamiki Hara's novel Natsu no hana (about "Summer Flowers") was published in 1947 .

Tamiki, who survived the bombing of Hiroshima just 1.5 km from the epicenter, committed suicide in 1951 by throwing himself in front of a train. The poet Tage Sankichi also survived the drop, but suffered damage to the lungs. He created the "collection of atomic bomb poems" comprising 25 poems, which he copied and illegally circulated in disregard of censorship. The poems dedicated to the Hiroshima Peace Assembly could not appear in book form until 1952. In the same year the well-known "Genbaku poetry collection" ( Genbaku Shishu ) was published by Mitsuyoshi Tōge. Another group of authors who had not witnessed the drops themselves processed the impressions of the Hibakusha with the help of documentary materials such as interviews and recordings. These include Ibuse Masuji with the novel "Kuroi Ame" ( Black Rain ), the so-called litérature engagée of Nobel Prize winners Ōe Kenzaburō , Sata Ineko and Oda Makoto . Kenzaburō Oe published his collection of essays Hiroshima-Nōto (English "Hiroshima Note") in 1965 , which emerged after repeated research and a detailed interview with the chief physician of the Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima. The third group of authors to which Murakami Ryū or Tsuji Hitonari belong use historical events as a framework for their works. The topic was probably given special attention by the comic novel "Barefoot through Hiroshima" ( Hadashi no Gen ) by Keiji Nakazawa , published in 1975 , which is listed by the Japanese authorities as atomic bomb victim number 0019760. In the present, the focus on the radiation victims of the Fukushima nuclear disaster is thematically linked to the atomic bomb literature .

to shape

prose

New forms: light novel, media mix, hypertext

From the 1980s on, a new form of entertainment novel (エ ン タ ー テ イ メ ン ト 小説, Entertainment shōsetsu ) appeared, aimed specifically at teenagers and young people as a buyer class and using Japanese manga as a form of expression. From the second half of the 1990s onwards, it was common to refer to these novels as light novels . One of the peculiarities of this genre, published under the technical name of light novel, is that the book cover is illustrated with manga and the text is provided with images. Individual forms of the light novel are: the “comic novel” (キ ャ ラ ク タ ー 小説, Character shōsetsu ), “Young Adult” (ヤ ン グ ア ダ ル ト) and “Junior Novel” (ジ ュ ニ ア ノ ベ ル).

Also in the 80s, writers like Kikuchi Hideyuki , Tanaka Yoshiki , Yumemakura Baku , Kurimoto Kaoru , Takachiho Haruka began to publish their works. The style of these writers is aimed at the middle school student group and is essentially aimed at entertainment and pleasure. Also in this area are the SF and fantasy publications by Mizuno Ryō , Kanzaka Hajime , Kadono Kōhei and others.By this group of works anime moves into social awareness, makes the bindings eye-catching through manga and anime representations by well-known illustrators and so anime and brings game development together with other media, the result is a media mix whose exposed and popular works expand the sales market. In recent years, for example, Arikawa Hiro and Sakuraba Kazuki , who first published part of their work as a light novel, have reissued these works as literary works.

Similar to the spread of the Internet and mobile phones, a change in text forms is looming. Many people are already receiving hypertexts , such as cell phone novels or e-books , which compete with the traditional book market. It remains to be seen what future developments will look like.

Poetry circles (selection)

- 1885 Ken'yūsha 硯 友 社("Society of Friends of Ink Stone"), members: Ozaki Kōyō, Yamada Bimyō, Ishibashi Shian, Maruoka Kyūka

- 1891 Waseda-ha 早 稲 田 派("Waseda University Group") Tsubouchi Shōyō

- 1909 Pan no kai パ ン の 会("The Pan")

- 1910 Shirakaba-ha 白樺 派("White Birch Group")

- 1910 Mita bungaku kai 三 田文 學会("Literary Society Mita" of Keiō University )

- 1929 Shinkō geijutsuha kurabu 新興 芸 術 派 倶 楽 部, members: Kawabata Yasunari, Kamura Isota, Ozaki Shirō, Ryūtanji Yū

- 1963 Shinyōkai 新 鷹 会("New Falcon Society") Hasegawa Shin

- 1945–2005 Shin nihon bungakukai 新 日本 文学 会("Society for New Japanese Literature")

- 1892 Nihompa 日本 派, Masaoka Shiki

- 1893 Asakasha あ さ 香 社("Society of Delicate Fragrances"), Naobumi Ochiai

- 1899 Negishi tankakai 根 岸 短歌 会( Negishi Tanka Community ), Masaoka Shiki

- 1899 Chikuhakukai 竹柏 会("Bamboo and Oak Society"), Sasaki Nobutsuna

- 1905 Shazensosha 車 前 草 社("Plantain Society")

- 1908 Araragi ア ラ ラ ギ(Magazine: Araragi )

- 1909 Jiyūshisha 自由 詩社("Society for the Free Poem"), members: Hitomi Tōmei, Katō Kaishun, Mitomi Kuchiha

Japanese literary magazines

reception

Japanese literature in German translation

In the course of the 20th century, Japanese literature became more and more accessible in different waves in German-speaking countries. The first notable high point lies between the years 1935 to 1943. Above all, a part of the scientific elite from the German Japanese studies of this time played an important role here. This movement was shaped by nationalist ideas. The Japanese people fascinated the scholars. For example, they saw parallels to German ideas about terms such as “loyalty” and “honor” in the worship of Tennō . This led to a relatively large number of translations, especially Japanese classics.

Another trigger for increased translation activities was, for example, the awarding of the Nobel Prize to Kawabata Yasunari in 1968. The international success of Japanese films in the 1960s - especially Kurosawa Akira's adaptation of Rashōmon (based on the short story by Akutagawa Ryūnosuke ) - or increased international interest the Japanese economic miracle in the 1980s triggered new demand. Translation activities received a further boost due to the focus on "Japan" at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1990 and the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Ōe Kenzaburō in 1994.

Must be mentioned the " Murakami Haruki phenomenon" was from that in Japan at the end of the 80s the speech, while in the financial newspaper of the German Book Trade in 1990, an article still raises the question: "Who is Murakami Haruki?" For more Murakami first came to fame in the German-speaking world in 2000 with the dispute in the literary quartet about his novel Dangerous Beloved (2000 by DuMont, original: Kokkyō no minami, taiyō no nishi, 1992 by Kōdansha ). After that, a few more works were translated in quick succession and Murakami seems to have become the best-known Japanese author in the German-speaking world, whose works can increasingly be found on the sales tables of large bookstore chains.

Situation on the German book market

Works from English (2007: 67.1%) and French (2007: 9.8%) account for the largest share of translations on the German-language book market.

There has been an extremely remarkable development for Japanese since 1999. Until then, the share of Japanese in total translation production seemed to level off between 0.2 and a maximum of 0.5 percent. Not even after the Japan year at the beginning of the 1990s and the Nobel Prize for Ōe Kenzaburō in 1994 a higher proportion could be achieved. In 1999 the proportion rose significantly to 0.9 percent. A first record was broken in 2001 when 124 titles were translated from Japanese, representing a share of 1.3 percent. Never before had nearly as many titles been translated. In 2004, a new proportionate high was reached with 1.6 percent of the total translation production for the year. Certain events have certainly made a small contribution to this development: In 1999, the Japan Foundation Translator Award was introduced by the Japanese Cultural Institute in Cologne , which is endowed with 5000 euros and awards a translation of fiction and non-fiction, and the controversy surrounding Murakami Haruki's dangerous lover , the Main topic South Korea at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2005 and of course the manga boom, which is noticeable in the statistics.

Currently, however, the proportion of translations from Japanese has declined again: in 2007 it was 0.8%. The “Index Translationum” of Unesco shows 1466 titles of Japanese literature translated into German (status: 2014).

See also

Remarks

- ↑ Methodologically, this distinction is based on Wolfgang Schamoni: Moderne Literatur. In: Klaus Kracht, Markus Rüttermann (Hrsg.): Grundriß der Japanologie. Izumi Volume 7. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, pp. 83-115.

- ↑ Art, in the sense of geijutsu (芸 術) in contrast to geinō (芸 能), (show) arts with a more entertaining character.

- ↑ See for example the Japanese edition of Britannica, Meikyō (明鏡) and Daijisen (大 辞 泉).

- ↑ The novel was published as a series title in the Yomiuri Shimbun . It remained incomplete because Koyo died in the process of writing.

- ↑ Text edition by Aozora Bunko

- ↑ As a series title first appeared from September to December 1908 in the newspaper Asahi Shimbun .

- ↑ This is the doctor of the same name (1805-1858) from the Edo period.

- ↑ What is meant is literature with aesthetic demands in contrast to mass and entertainment literature.

- ↑ The magazine appeared in the forerunner of Kōdansha until 1957 and broke through the circulation number of 1 million copies for the first time.

- ↑ These are crime stories with a plot that is located in Japanese history.

- ↑ The new forms mentioned here, however, are at best marginal areas of literature even according to a broad understanding.

literature

Japanese primary literature

- 青 空 文庫. Retrieved on February 23, 2014(Japanese,Aozora Bunko- digitization project of texts from the Shōwa and Meiji periods).

- 日本 古典 文学大系( Nihon koten bungaku taikei , Compendium of Classical Japanese Literature). Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo (100 volumes, 1957–1968).

- 新 日本 古典 文学大系( Shin-Nihon koten bungaku taikei , New Compendium of Classical Japanese Literature). Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo (1989-2005).

- 日 近代 典 文学大系( Nihon kindai bungaku taikei , Compendium of Modern Japanese Literature). Kadokawa Shoten, Tokyo (60 volumes, 1970–1975).

Translations of Japanese literature

- Modern Japanese literature in German translation. A bibliography from 1868–2008 . In: Jürgen Stalph, Christoph Petermann, Jürgen Wittig (eds.): Iaponia Insula, studies on the culture and society of Japan . tape 20 . Iudicium, Munich 2009 (Listed 412 authors and around 1800 translations.).

- Japanese literature in German translation. Japanese Literature Publishing Project [JLPP], 2006, accessed on February 23, 2014 (Large selection of literature translated into German. Only books that are currently available in bookshops are included.).

- Japanese Literature in Translation Search. The Japan Foundation, 2013, accessed February 23, 2014 (English, Free online database containing translations of Japanese literature.).

- Premodern Japanese Texts and Translations. Meiji University, August 3, 2009, accessed February 23, 2014 (Bibliography of translations of Japanese works before 1600).

- Japanese library from Insel Verlag. Freie Universität Berlin, February 24, 2014, accessed on February 24, 2014 (32 titles have been published).

- Edition Nippon by Angkor Verlag. Angkor Verlag, accessed on February 24, 2014 (including e-books).

- Japan Edition by be.bra Verlag. be.bra Verlag, accessed on February 23, 2014 .

- Jun Nasuda International Youth Library, Fumiko Ganzenmüller: Japanese children's and youth literature translated into German (1945–1992): list of books . International Youth Library, Munich 1992.

- Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit: A dream bridge into a cooked-out wonderland: A Japanese reading book. Insel, Frankfurt, Leipzig 1993, p. 220 .

- Jürgen Berndt, Hiroomi Fukuzawa (ed.): Snapshots of Japanese literature . Silver & Goldstein, Berlin 1990.

- Barbara Yoshida-Krafft (Ed.): The eleventh house. Stories by contemporary Japanese authors . iudicium, Munich 1987.

- Horst Hammitzsch (ed.): Japanese fairy tales . Rowohlt, Hamburg 1992.

- Tadao Araki, Ekkehard May (Ed.): Time of the cicadas. Japanese reading book . Piper, Munich 1990.

- Yukitsuna Sasaki, Eduard Klopfenstein, Masami Ono-Feller (eds.): If there weren't any cherry blossoms ... Tanka from 1300 years . Reclam, 2009.

- Jiro Akagawa: Japanese Everyday Life. Short stories . Buske, Hamburg 2009 (the only bilingual paperback so far published.).

Secondary literature

- Literary history

- Paul Adler, Michael Revon: Japanese Literature. History and selection from the beginning to the most recent. Frankfurter Verlagsanstalt, Frankfurt (probably 1926).

- Karl Florence : History of Japanese Literature . In: The literature of the east in individual representations . Tenth volume. CF Amelangs Verlag, Leipzig 1906 ( Online in the Internet Archive - the only complete literary history written by a German from the beginnings to around 1900.).

- Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit : Japanese contemporary literature: a manual . Edition Text + Criticism, München 2000.

- Katō Shūichi : History of Japanese Literature . Scherz, Bern, Munich, Vienna 1990 (The German translation is out of print and has translation errors. The English paperback edition is still available from Kodansha.).

- Cecile Sakai: Histoire de la littérature populaire japonaise: faits et perspectives (1900–1980) . Editions L'Harmattan, 1987.

- Overview presentations and topic-related work

- New Concepts in Japanese Literature? National literature, literary canon and literary theory. Lectures of the 15th German-speaking Japanologentag: Literature II . In: Lisette Gebhardt , Evelyn Schulz (eds.): Series on Japanese literature and culture Japanology Frankfurt . tape 8 . EB, Berlin 2014.

- Yomitai. New literature from Japan . In: Lisette Gebhardt (ed.): Series on Japanese literature and culture Japanology Frankfurt . tape 3 . EB, Berlin 2013.

- Jürgen Berndt (Hrsg.): BI-Lexicon East Asian literatures . Bibliographisches Institut Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, p. 53-77 .

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Murder in Japan. The Japanese crime thriller and its heroes: From World War II to the present . Iudicium, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-89129-745-9 .

- Junkô Ando, Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, Matthias Hoop: Japanese literature in the mirror of German reviews . Iudicium, Munich 2006.

- Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit: What does it mean to understand Japanese literature? Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- Siegfried Schaarschmidt, Michiko Mae (Hrsg.): Japanese literature of the present . Carl Hanser, Munich 1990.

- Lisette Gebhardt : After dark. Contemporary Japanese literature under the sign of the precarious. EB-Verlag, Berlin 2010.

- Ekkehard May: Premodern Literature . In: Klaus Kracht, Markus Rüttermann (Hrsg.): Grundriß der Japanologie . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, p. 63-83 .

- Ekkehard and Katharina May: Literature . In: Horst Hammitzsch (Ed.): Japan Handbuch . 3. Edition. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1990, Sp. 873-1104 .

- Wolfgang Schamoni: Modern Literature . In: Klaus Kracht, Markus Rüttermann (Hrsg.): Grundriß der Japanologie . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, p. 83-115 .

- Matthias Koch: On the translational bilateral symmetry between Germany and Japan, or: who translates more? In: A certain color of strangeness. Aspects of translating Japanese-German-Japanese (= monographs from the German Institute for Japanese Studies of the Philipp-Franz-von-Siebold-Foundation. 28). Iudicium, Munich 2001, pp. 45-75.

- Eduard Klopfenstein: Departure to the world. Studies and essays on modern Japanese literature. be.bra verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-95410-022-4 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hiroomi Fukuzawa: On the reception of the European scientific vocabulary in the Meiji period. (PDF) In: NOAG 143. OAG, 1988, pp. 9-19 , accessed on February 26, 2014 .

- ↑ Kotobank

- ↑ 於 母 影. In:ブ リ タ ニ カ 国際 大 百科 事 典 小 項目 事 典at kotobank.jp. Retrieved March 8, 2015 (Japanese).

- ^ Beata Weber: Mori Ogai and Goethe. (No longer available online.) Humboldt University Berlin, archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; accessed on March 8, 2015 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ 楚 囚 之 詩. In:大 辞 林 第三版at kotobank.jp. Retrieved March 8, 2015 (Japanese).

- ↑ Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit: Japanese contemporary literature . edition text + kritik m Richard Boorberg Verlag GmbH & Co, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-88377-639-4 .

- ^ Thomas Hackner: Futurism and Dadaism in Japan . In: Hilaria Gössman, Andreas Mrugalla (Ed.): 11th German-speaking Japanologentag in Trier 1999 . tape II. . Lit Verlag, Münster et al. 1999, p. 239–249 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed March 1, 2014]).

- ↑ 新 感 覚 派. In:デ ジ タ ル 版 日本人 名 大 辞典 + Plus at kotobank.jp. Retrieved March 1, 2014 (Japanese).

- ↑ Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit: New tendencies in modern Japanese literature . In: Klaus Kracht (Ed.): Japan after 1945 . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1979, p. 102–114 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed March 1, 2014]).

- ↑ See: aozora.gr.jp横 光 利 一:新 感 覚 派 と コ ン ミ ニ ズ ム 文学at Aozora Bunko

- ↑ Yamagiwa, Joseph Koshimi: The Neorealist School. In: Japanese literature of the Shōwa period: a guide to Japanese reference and research materials. Center for Japanese Studies Publications, 1906, p. 4 , accessed March 1, 2014 .

- ↑ 新興 芸 術 派. In:デ ジ タ ル 版 日本人 名 大 辞典 + Plus at kotobank.jp. Retrieved March 1, 2014 (Japanese).

- ↑ 新 心理 主義. In:デ ジ タ ル 版 日本人 名 大 辞典 + Plus at kotobank.jp. Retrieved March 1, 2014 (Japanese).

- ↑ Florian Coulmas : Hiroshima. History and post-history . CH Beck, Nördlingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58791-7 , VI atomic bomb literature, p. 127 .

- ↑ See also: Daniela Tan: Who's talking in my dreams? Spilled memories - Hiroshima . In: Christian Steineck, Simone Müller (ed.): Asian Studies - Études Asiatiques . tape LXIII , no. 3 . Peter Lang Verlag, Bern 2009, p. 640–675 , doi : 10.5167 / uzh-23809 ( zora.uzh.ch [PDF; accessed on February 12, 2012]).

- ↑ Kazutoshi Hamazaki: Early Japanese Atomic Bomb Literature. (PDF) In: Bulletin of Faculty of Education, No.67. Nagasaki University, June 30, 2003, p. 12 , accessed February 12, 2012 .

- ↑ a b Kaiko Nambo: Voices of Pain. In: Cicero Online. July 29, 2010, accessed February 12, 2012 .

- ^ Index Translationum - World Bibliography of Translation. UNESCO, July 1, 2013, accessed February 23, 2014 .

Web links

- Japanese Text Initiative. University of Virginia Library, April 2, 2012, accessed March 1, 2014 (English, digitized copies, and English translations of “classic” older Japanese texts).

- き き み 名作 文庫(Kikimimi meisaku bunko). Tokyo FM Broadcasting, 2010,accessed March 1, 2014(Japanese, Japanese literature read as a podcast).

- 歌舞 伎 へ の 誘 い(Kabuki e no izanai). Japan Arts Council, 2006,accessed March 1, 2014(Japanese).