Scharnhäuser (Frankfurt am Main)

The Scharnhäuser , partly also known as the Alte and Neue Häringshock or Three Fish after their original sales function , were two historic semi-detached houses in the old town of Frankfurt am Main . The south facade of the houses faced the Heilig-Geist-Platz in Saalgasse , while the north faced Bendergasse shortly before it crossed the Lange Schirn cross-connection . The house address was Saalgasse 20/22 or Bendergasse 13/11 .

The houses were not only relatives by name, but also structural relatives of the famous New Red House on the market , which was built on solid oak pillars : the ground floors of both buildings were largely split into a passage between Bender- and Saalgasse. In addition, one of the houses had gained a certain fame, at least in the Frankfurt area, when the young Johann Wolfgang Goethe worked there as a lawyer for the then owner in the second half of the 18th century.

In March 1944, the Scharnhäuser burned down after the Allied bombing raids on Frankfurt, along with the rest of the old town. In the 1980s, the parcels of the buildings, like those of the rest of Saalgasse, were built over with postmodern townhouses, so that they must be counted among the lost monuments and Goethe sites in Frankfurt's old town.

history

The emergence of the Scharnhäuser in the Middle Ages

As with the majority of the buildings in Frankfurt's old town, there is no monograph on the Scharnhaeuser , but only a large amount of initially unrelated information in the form of archaeological findings, documentary mentions and a few photographs. There are also some architectural detail drawings of the so-called old town photograph from the early 1940s as well as notes by the Treuner brothers, on which their model of Frankfurt's old town is based.

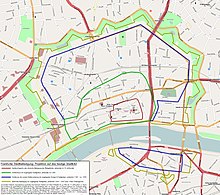

Archaeological excavations have shown that Saalgasse , presumably as an eastern extension of Alte Mainzer Gasse , was probably a paved road as early as Carolingian times. Together with the market , which is also verifiable for this period , it formed the only east-west passage in the Palatinate area, which was fortified around the year 1000 . It is obvious that a later development was first built along or between the two streets. The exact time is difficult to narrow down, but due to the oldest Romanesque house cellars it can hardly be set before the 11th century.

The earliest, if only indirect, documentary mention of what was at the place of the Scharnhäuser, i.e. on the northern edge of the middle Saalgasse, can be found in a document from 1324 issued about the neighboring house to the west, Zum Arn . The reason for the notarization was the sale of 2 marks money and 36 marks pfennigs of perpetual Gülte on the house by a knight Johann von Cleen and his wife Kusa to the Frankfurt citizen Hermann Knoblauch .

With regard to the Scharnhäuser u in the aforementioned source. a. the talk of "hus zum Aren daz da liget zu Franckenford by the nuwen Fleischarren no hus, daz da heyzet zu der Hangenden Hant". So there was an open meat stall next to the neighboring house, which must have been relatively new in 1324. The house at the hanging hand , which is also mentioned in the text passage, refers to the building opposite with the address Saalgasse 23, which took its name from the house sign, a wooden hand hanging on a chain.

Only a few decades later, in 1350, the place is again conspicuously mentioned in the Liber censuum of Baldemar von Petterweil , who was canon of St. Bartholomew's monastery at the time. In the aforementioned book, which is still preserved today, he provided the earliest known topographical description of Frankfurt's old town. He wrote about the cross connections between Bendergasse and Saalgasse: "Sancti Spiritus et Doliatorum duo, orientalis Domus macellorum, occidentalis vicus artus Vitrorum" .

Another writing by Baldemar from the 14th century, the Liber redituum , differentiates even more finely into a domus macellorum orientalis and a domus macellorum occidentalis , that is, a right and a left “house of meat banks ”. The publicly pervasive form of the buildings, which was apparently already special at that time, is emphasized by the fact that he describes it as equivalent to other, pure passageways, but explicitly differentiated it from an ordinary alley ( vicus ) in his choice of words ( domus ) .

Well over 100 years later, an entry in the vicariate book of St. Bartholomew's monastery in 1481 allows conclusions to be drawn about the Scharnhäuser, where it says: “sub domo et tecto macellorum super celario dicto daz gewelbe” . According to this, a house with a vaulted cellar must have existed on the site of the Scharnhäuser. The existence of such a vaulted cellar under the Scharn houses was confirmed at the latest in the old town excavations after the Second World War and was also explicitly mentioned in the cellar investigation reports of 1954/1955. In addition, a corbel on the house at Saalgasse 20 was dated 1546.

When exactly the Fleischschirnen became two houses can no longer be clearly clarified from the aforementioned sparse information. Much of the information provided by Baldemar von Petterweil points to the 14th century, but the formal language of the buildings that were still in Baroque style in the 20th century revealed only a late Gothic core building from the transition period, i.e. around the years 1470–1550 by far the largest part of Frankfurt's old town was attributable. The most important clues for this are the only slight cantilevering of the buildings, the ornamental treatment of the original ground floors on Bendergasse and the corbel with a matching date.

The urban and economic environment

The Heilig-Geist-Platz , where the two Scharnhäuser stood, was a funnel-shaped square about half the length of the Saalgasse. East of it began the oldest Frankfurt Jewish quarter, traceable from the middle of the 12th century, which extended to the cookshop to the east of the cathedral . Only after the forced resettlement of the Jews in a ghetto from the middle of the 15th century did the name of Saalgasse transfer to the street section they lived in. As everywhere in the old town, sacred and public buildings can be documented from the 13th century onwards, and private buildings from the early 14th century onwards, for the already important street within the oldest city wall (see previous section) prove.

After the Staufer Saalhof from the 12th century, which gave the Saalgasse its name, a church building with a hospital hall was probably the oldest building on the street, the Heiliggeistspital, first attested in 1267 . The hospital church stood in the south of the square, directly opposite the later Scharnhouses. To the south-east, in the Metzgergasse that opened up here , a pointed arched portal led into a converted inner courtyard with the supply buildings, some of which came directly against the city wall on the Main. The complex, which was demolished in 1840, gave its name to both the square in front of it and the alley to the west and the city gate on the Main - Am Geistpförtchen and the actual Geistpförtchen .

At least since the 1320s is also a great bread shop called was bread Hall , the Holy Spirit cookies. After the establishment, the whole square was then also known as the Weckmarkt or bread market . The bread hall took the place of two later buildings east of the Scharnhäuser until it was demolished around 1555. In the same year, the council had passed a resolution that forbade bakers from continuing to sell their bread there, and initially designated the cloister of the barefoot monastery as the future point of sale . Later on, bread was sold south of the cathedral at the point that is still called the Weckmarkt today.

Thus, the Scharnhäuser stood in one of the most important places between the cathedral and the Römer , which, due to the many supply buildings, probably not only served as a market, but was also a point of social exchange. With the Heiliggeistspital in the south, the core of the butcher's quarter in the south-east, the bread hall and the meat stalls in the north, as well as walking routes of roughly the same length to all other important places in the old town, the houses were in a very prominent and lucrative location for the measurement business, which takes place twice a year .

The further development in the early modern period

The further history up to the baroque period is, apart from some general information, in the dark. City historian and topographer Johann Georg Battonn showed a few documented mentions of the buildings up to the 17th century, which, however, can hardly be put into context without further research on sources. In particular, the owner's history is complex and difficult to reconstruct, as the houses were divided into various parts that not only had different owners, but also various uses (shops, apartments, etc.).

After the Scharnhäuser had apparently only served the meat sale from which they once emerged until the early modern period, a change occurred at the end of the 16th century that gave the buildings their names, which have been preserved up to the modern age. 1581 was first held from domus macellorum from domus salsamentarium spoken, and in 1586, the term is documented as fish house . Apparently at the beginning of the 17th century the traditional name of Alte and Neue Häringshock was established , whereby the house Saalgasse 20 must have received the name earlier than Saalgasse 22 due to its name.

What led to the fact that the fish sales in the axis of the old butcher's quarter between the New Red House on the market , along the Langen Schirn down to the Metzgergasse, can no longer be clarified. Although the sale of salted herrings was relocated by the council to the food stall east of the cathedral at the beginning of the 18th century due to the unpleasant smell associated with it, and the houses came back into the possession of butchers, they still got their peculiar name in popular parlance.

Regarding the external appearance of the houses, the first city maps of the 16th century, especially that from Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia from 1545 and the siege plan of the city from 1552, are not very productive. At most two-story, gable-facing houses can be recognized without the structural peculiarities of the Scharnhäuser. In contrast, as is so often the case, the Merian plan from 1628 shows an excellent level of detail , on which even the front doors, subtracted later changes to the buildings, are located where they could be seen until 1944. The plan also shows the building with the wide ground floor passages, measuring shops and two attic floors. On the other hand, the atria between the buildings on Bender- and Saalgasse, which inevitably had to result from the semi-detached house situation, cannot be seen.

The legal dispute over the old woman Häringshock

In the middle of the 18th century, when the Scharnhäuser were again in the hands of butchers after the herring sales had ended, the Alte Häringshock belonged to the master butcher Nikolaus Hemmerich , the house next door to his widowed mother. Since renting the houses in the old town center was very profitable, especially during the measurement period, Hemmerich decided in 1767 to enlarge the built-up area of his house. Because the passage had the considerable height of around 14.75 feet , i.e. over 4 meters , he saw the establishment of a room about 6.5 feet (just over 1.80 meters) high, which should be timbered into the passage from above , the easiest way to increase your rental income.

However, since Hemmerich did not own the entire house, both residents, whose apartment faced the inner atrium of the building, and the owners of shops on the ground floor protested the project. Above all, they criticized the further reduction in natural light threatened by the measure and the no longer guaranteed access for the fire brigade in the event of a fire. The building authority then followed this line of argument and issued a negative decision.

Due to the high additional income to be expected from the structural expansion - after a failed settlement attempt - a court case before the Frankfurt lay judges' court . In this, Hieronymus Peter Schlosser , the brother of Johann Wolfgang Goethe's brother-in-law Johann Georg Schlosser, represented the neighbors, Goethe's uncle Johann Jost Textor acted as the master butcher's lawyer. In the course of the process, a foreign arbitration panel was finally called upon, whose ruling in 1770, however, left the last word with the building authorities, which, as expected, again judged the building project to be negative. In addition, the dispute had meanwhile expanded to the point that there were now doubts as to whether the passage through the house should be viewed as private, but rather as an alley and thus municipal property. The city apparently feared a dangerous precedent here , as there were hundreds of built-up alleys and eaves in the old town at that time, where property rights were no less doubtful, let alone ever been treated legally.

From then on, Goethe's uncle had to deal with Gerhard Matthäus Wallacher , who had been entrusted with the matter as advocatus fisci by the building authority . The case was now being dealt with again in Frankfurt before the lay judge's court, without, however, being able to come to a result despite excessive correspondence. In September 1771 Johann Jost Textor was elected to the city council and could therefore no longer continue his mandate. Although unproven, he certainly influenced Hemmerich to hand over the case to his nephew Johann Wolfgang Goethe. In August of the same year it was only the second case for him to be admitted to the bar. His activity began with a letter dated November 6, 1771, which offers a good insight into the legal terminology of the time:

- “Well and noble drills! Accordingly, in an externally rubricated matter, the Advocatus Fisci not only in a venereal Decretdo de 17 Jul. 1771, insinu. July 20, ejusdem scheduled deadline of eight days, but also against all hopes, he would finally bring his possibly replicable writing even without warning, let this be crossed out disobediently for a long time, so now find it most necessary, Ewre pro praefigendo termino ulteriori eoque praejudiciali gantz gantz to ask. Desuper Ewrer submissively obedient Nicolaus Hemmerich. Concept JW Goethe Licentiat. "

The process dragged on for years, during which external law faculties were sought again. They asked the city to prove that the passageways were also public property, but this did not succeed despite a thorough examination of Hemmerich's and his mother's letters of purchase. As part of the constant extension of the deadline, Goethe warned several times about a decision that was finally made on June 29, 1774 by an external arbitration board in Helmstedt in favor of Nikolaus Hemmerich. Although, according to the documents of the time, the city even wanted to call the Reich Chamber of Commerce, there are no files or correspondence about a process, which is why the council either rejected the plan or was rejected. Goethe had thus won the process.

The structural redesign of the Scharnhäuser must have taken place only a little later. The exact extent of the alterations can only be assumed today due to archival documents that are no longer available, based on the comparison of older images and analogies, and can only be determined from the exterior. For example, it can be said with certainty that it could not have been a completely new building, as the houses standing up to 1944 had storey overhangs that were only allowed to be preserved in old buildings at the end of the 18th century due to building regulations. It is also certain that Hemmerich's house received the accused room; In addition, the upper floors were probably also heavily modified in order to provide them with larger windows in a contemporary shape. Finally - contrary to the illustration on the plan from 1628 - the eaves-facing roof was fitted with a massive late-baroque dwelling .

Hemmerich's mother's house was remodeled in a very similar way at the same time as the entire ground floor was given a Louis-seize-style facade, but with the same passage height . The dwarf house seen there with the typical Frankfurt nose was undoubtedly much older, which also fits with the roof, which had a steeper slope than the neighboring house. What is remarkable and characteristic of the complicated ownership structure is that the renovations completely left out the back of the house on Bendergasse, thus preserving its late Gothic character. From the inside, the only thing that emerges from the trial files is that the von Hemmerich house stood on four pillars, details of the construction, such as those of the structurally closely related New Red House on the market , are completely missing.

19th and 20th centuries, World War II and the present

In the early 19th century, a radical change began in the structures of the old town. Even in the Baroque period, the late Gothic ensemble between the cathedral and the Römer was only held in low esteem from the point of view of prevailing architectural ideals. After the city fortifications were abandoned by around 1820, representative neo-classical , and later also Wilhelminian-style, residential areas were built around the old town center within a few decades . First the upper and then the middle class left the original houses in the old town center, which had been in use for generations, and left the old town mainly to workers who poured into the town as a result of the industrial revolution, who could not offer them enough affordable housing. With the dwindling importance of the classical mass and the final decline of the guild system in 1864, other fixed points in the old town structures that had remained unchanged for centuries fell apart within a few years.

However, as in many other former imperial cities , there was no major historicist transformation or even a demolition of the old town. In particular, the most valuable part between the cathedral and the Römer remained largely untouched, although around 1900 it was not uncommon for more than a dozen families to live under literally medieval conditions in unrenovated apartments, which were created by dividing up once spacious patrician houses intended only for one family. In spite of all the grievances and the bad reputation of the old town at the time, many old relationships were still able to be maintained, for example in the address book of 1877 in the Scharnhau houses, among other professional groups, there are still butchers.

In the course of the first city tourism in the German Empire , only individual representative buildings and parts of the old town were renovated. In addition to the Roseneck or the five-finger cookie, this also included the Heilig-Geist-Platz with the cathedral tower towering behind it, a particularly "old German" motif according to the understanding of the time, which is often found on the city's earliest photo postcards . This is probably one of the reasons why the square sank less than some other areas of the old town. Only from 1922 onwards did the Association of Old Town Friends, on the initiative of the historian Fried Lübbecke , advocate a general renovation of the area and the improvement of living conditions . He wrote in the Frankfurter Zeitung on June 7, 1922:

- "... many patrician houses have been reduced to magazines - in short: lovelessness and overpopulation with a lack of culturally superior families, old age and low rental income, last but not least prostitutes and their followers ensure that our old town is not as it is in the interest this very unique monument of German art and the past should be ... "

In 1924, the renovation of the Scharnhäuser took place. a. Removed historicist modifications and restored its old paintwork as well as the painting with Louis-Seize ornamentation on the Neue Häringshock. Finally, the Alte Häringshock received a plaque with the inscription:

- 1771-1772

- stayed Johann Wolfgang

- Goethe

- as advocate of the butcher

- masterly Hemmerich often in

- this house and won

- for the property

- first trial.

Under the National Socialist rule, the old town's recovery was continued with the aim of a fundamental renovation of the building fabric of the old town. By the early 1940s, around 600 buildings had been thoroughly renovated and many others had been externally renovated. In the same year, Frankfurt was targeted for the first time by air raids , which, however, did little damage until the end of 1943. It was not until March 1944 that several major attacks hit Frankfurt and triggered a firestorm that destroyed the entire medieval old town. The hinge houses, built of wood behind their baroque cladding down to the ground floor, burned down completely.

By around 1950, the ruins of the old town between the cathedral and the Römer, including numerous reconstructable ground floors made of sandstone , were completely cleared away. From the Römerberg there was a situation of a huge undeveloped space that had not been seen for more than a millennium. The cellars that have been preserved almost everywhere and that often go back to the founding of the city, including those of the Scharnhäuser, had, according to their archaeological documentation, in the following decades. a. make space for the construction of an underground car park and the Dom-Römer subway station . In the 1980s, in the course of the reconstruction of the buildings on the Saturday Mountain - in the vernacular historically incorrect Ostzeile - the Saalgasse was also rebuilt in post-modern forms. On the parcel of the Scharnhäuser, however, is the south wing of the Schirn Kunsthalle , which was also built at the time and protrudes into the perimeter of the block. So today nothing reminds of the former Frankfurt Goethe site.

literature

- Johann Georg Battonn: Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volume III . Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1863, p. 302

- Johann Georg Battonn: Local Description of the City of Frankfurt am Main - Volume IV . Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1864, p. 92 u. 96-104

- Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction - Volume 2, south . Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, p. 830

- Georg Ludwig Kriegk: German cultural images from the eighteenth century. In addition to an appendix: Goethe as a lawyer . Verlag von S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1874, pp. 296-314

- Hans Lohne: Frankfurt around 1850. Based on watercolors and descriptions by Carl Theodor Reiffenstein and the painterly plan by Friedrich Wilhelm Delkeskamp . Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1967, p. 167

- Fried Lübbecke , Paul Wolff (Ill.): Alt-Frankfurt. New episode . Verlag Englert & Schlosser, Frankfurt am Main 1924, p. 53 u. 54

- Walter Sage: The community center in Frankfurt a. M. until the end of the Thirty Years War. Wasmuth, Tübingen 1959 ( Das Deutsche Bürgerhaus 2), p. 74 u. 75

References and comments

- ↑ These and all the following address details correspond to the last Frankfurt address book from 1943, published before the destruction of the old town in World War II (unless explicitly stated otherwise).

- ^ Karl Nahrgang: The Frankfurt old town. A historical-geographical study . Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1949, p. 56; the oldest street layer found at a depth of 3.10 meters was cut by the house cellars of the oldest Judengasse (eastern half of today's Saalgasse, which at that time was only known as Weckmarkt), which was only proven in Frankfurt from the middle of the 12th century.

- ↑ Three Middle High German copies or copies of the certificate are known. Johann Georg Battonn ( Local Description of the City of Frankfurt am Main - Volume IV . Association for History and Archeology of Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1864, pp. 91 and 92) cites a copy with the cryptic source LVB Saec. XIV. Vic. XXVI presumably from a copy book of the Leonhardsstift, at Johann Friedrich Böhmer ( document book of the Reichsstadt Frankfurt . Volume II 1314-1340. J. Baer & Co, Frankfurt am Main 1901-1905, p. 186 and 187, document no. 234) two more prints from books of the Bartholomäusstift.

- ↑ resulting from medieval guilds public meat market were altfrankfurterisch as Schirnen known a word from the Middle High German Scharn or Schrannenplatz or Old High German Scranne was derived, which really only so much as open stall meant. When the guilds became meaningless in Frankfurt am Main in the middle of the 19th century with the introduction of the freedom of trade, the term Schirn was only retained in the Red House on the market, which was destroyed in 1944 with the old town.

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 74 and 75; Battonn saw the house with the house sign after which it was named in Bedebuch 1320, before it was replaced by a new building around 1800, quote from the manuscript: “About 30 years ago you saw a big hand on an iron one Chain hanging from the superstructure in front of the front door; but now a small hand with the old name is carved out over the door of the newly built house. "

- ↑ Last known print see: Heinrich von Nathusius-Neinstedt : Baldemars von Peterweil description of Frankfurt . In: Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art. Third episode. Fifth volume . K. Th. Völcker's Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1896, pp. 1-54.

- ↑ Loosely translated "Saalgasse and Bendergasse have two [cross connections], on the right the meat banks' house, on the left the Gläsergasse [behind the later Schwarzer Stern house on the Römerberg]" .

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 101 and 102.

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 101 and 102.

- ^ Walter Sage: The community center in Frankfurt a. M. until the end of the Thirty Years War. Wasmuth, Tübingen 1959 ( Das Deutsche Bürgerhaus 2), p. 75.

- ^ Battonn IV, p. 92.

- ^ A b Franz Rittweger, Carl Friedrich Fay (Ill.): Pictures from the old Frankfurt am Main. According to nature . Publishing house by Carl Friedrich Fay, Frankfurt am Main 1896–1911; according to the caption by Franz Rittweger for the picture "The free space in the Saalgasse with a view of the cathedral".

- ^ Food, p. 62.

- ^ Batton III u. IV to Saalgasse.

- ^ Georg Ludwig Kriegk: German citizenship in the Middle Ages. Rütten and Löning, Frankfurt am Main, 1868, p. 76 u. 77.

- ↑ Battonn IV, pp. 96-100; First written mention of “Brothallen gein dem sichenspital” in 1327.

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 100; Imprint of marginal notes by Dean Latomus in a book of vicaries kept from 1453: “Anno 1555 Senatus deturbavit vendentes de hoc mensa ut etiam de ceteris: et instituit illos in coenobio Franiscano” , added on the following page with: “A. 1555 Senatus prehibuit ibi vendere ” .

- ^ Batton IV, 92 and 102-104.

- ^ Battonn IV, p. 102.

- ^ Battonn IV, p. 103.

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the following presentation follows the work of the city archivist Georg Ludwig Kriegk, which was elaborated on the basis of the Criminalia files: German cultural images from the eighteenth century. In addition to an appendix: Goethe as a lawyer . Verlag von S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1874, pp. 296-314.

- ↑ 1 Frankfurt foot corresponds to 28.461 cm.

- ^ Fried Lübbecke, Paul Wolff (Ill.): Alt-Frankfurt. New episode . Verlag Englert & Schlosser, Frankfurt am Main 1924, p. 53 u. 54.

- ^ Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction - Volume 2, south . Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, p. 830

- ^ Cf. Christian Holl: Hübsch uglich , in: moderneREGIONAL 16, 1 (January 2016).

Web links

- Saalgasse with the Scharnhouses. altfrankfurt.com

- Scharnhäuser . In: Virtual old town model Frankfurt am Main