Stadtwaage (Frankfurt am Main)

The Stadtwaage was a historic stone house in the old town of Frankfurt am Main , which has been urban since its construction . The northern eaves side of the building faced the Weckmarkt south of the cathedral , the eastern gable side towards the Große Fischergasse with the Roseneck group of houses and the mostly built-in southern eaves towards the An der Schmidtstube alley . In the west, the building adjoined Weckmarkt 3 , also known as the New Department Store , which housed the undertaker's office until it was demolished . The street address was Weckmarkt 1 .

The history of the building is closely intertwined with the old Jewish quarter of the city and the oldest Frankfurt synagogue , in the place of which it was built in 1503. After it was demolished in 1874, the city scales were replaced by a neo-Gothic warehouse building for the Frankfurt City Archives until 1877 , which in turn was completely destroyed along with the old town in 1944 during the air raids on Frankfurt am Main .

After the war, the plot and large parts of the old street network were reshaped by simple residential and commercial buildings, which, in addition to the historic canvas house, still characterize the image of the Weckmarkt today, so that nothing is reminiscent of the synagogue, the city scales or the historicist city archive.

history

Prehistory and the old Jewish quarter

In the high Middle Ages , the cathedral was almost completely surrounded by secular buildings - as in many cities of that time. Here was the nucleus of Frankfurt , which had developed from the former royal palace , and also the old town hall of the city, first mentioned in 1288 on the site of the current church tower. In the absence of pictorial representations and the fact that this area had reached the state at the beginning of the early modern period in which it was then almost unchanged until its complete destruction in World War II , the topographical situation of the Middle Ages can only be approximated on the basis of documented mentions and reconstruct less archaeological findings.

It is undisputed that the oldest Jewish quarter of the city was to the southwest, south and southeast of the cathedral. This proximity of the Jewish quarter to the city administration, which has been independent since 1311, and also to the church was unusual in a national comparison and yet characteristic of Frankfurt, which had from time immemorial one of the largest and most independent Jewish communities in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . The area dominated by Jewish residents was until the middle of the 14th century in the east by the Fahrgasse about level with the flour scales , in the north by the cookshop and the southern edge of the churchyard and in the west by the Heilig-Geist-Platz in der Saalgasse loosely bounded.

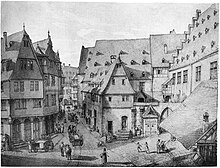

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein , 1862)

The churchyard was extended in the north and east as far as Born- and Kannengiessergasse , but in the south it was probably much closer than it is today to the cathedral, as the Alte Judengasse , which must be understood as the main street of the quarter, is between the church - until the 1340s without transepts - and forced the later Weckmarkt . The subdivision of the Weckmarkt was shifted much further north than in the early modern period or today, so that the alley was hardly more than two meters wide. The Affengasse with the eponymous corner house Zum Affen at the western end of the Judengasse led up to the cathedral and then to Bendergasse at the intersection with Saal- and Schlachthausgasse .

The free-standing block of houses with the later canvas house was also an integral part of the Jewish quarter for a long time. This is evidenced by numerous documents and the topographical description of the area by Baldemar von Petterweil in 1350. East of Gumprachtsgasse , which intersected the block in north-south direction, was the Jewish dance or playhouse , to the east of it was the so-called old Jewish school . The latter building was the oldest synagogue of the Jewish community in Frankfurt, which has been documented since the 12th century. It was destroyed during the pogroms in 1241 - in this context its first mention - and in 1349, but evidently rebuilt again and again in the same place of similar cubature.

After the pogrom of 1349 , in which almost the entire Jewish population of the city was murdered, a fire that was set destroyed large parts of their ancestral living quarters and damaged the cathedral that was currently under construction, the entire area between the churchyard and the Main was a desert of rubble. On the basis of a recently concluded contract with Emperor Charles IV , the Jewish ownership of the area passed to the council, which in the following years had to fend off numerous desires for this extremely conveniently located property, and was largely successful.

The city fathers were only defeated in the dispute with the Bartholomäusstift over the property in the northern Judengasse, i.e. directly next to the church. This was a great success for the monastery, as the churchyard was significantly reduced in size by the construction of the south transept of the church in 1352 and 1353, which it was able to compensate for by adding the old plots. The churchyard wall, built from 1351 onwards, probably followed the southern block edge of the old Judengasse and met the rear of Affengasse in the west.

The remaining land was again given to private individuals by the council, including Jews who were only hesitantly returning to Frankfurt. The most prominent example of a company in the field of secular construction on the site of former Jewish houses was the Fürsteneck house on the corner of Fahrgasse , which was built by Johann von Holzhausen in 1362 and was preserved until 1944 . But the city itself also used the old land: in 1365 there was talk of the construction of a city scale in Affengasse for the first time , which was apparently completed by 1372.

The canvas house , which has been preserved to this day, was also built in 1399 on the site of three Jewish houses that had burned down. In 1462 the slowly growing Jewish community was forced to move to the ghetto outside the city wall . The city had a heraldic eagle painted on public Jewish buildings such as the synagogue, which were now unused, to reinforce its claims; the few houses that came into Jewish possession after 1349 soon went to private individuals or were bought by the church. With the demolition of the old churchyard wall as part of the Reformation in 1537 and its new construction after decades of dispute, the churchyard received its current narrow boundaries in 1571, erasing the last traces of the high medieval topography of the place.

Transition of the weighing fair and new construction of the city scales

Although written documents about only one scale in Affengasse exist for the end of the 14th century, there were probably several such institutions in the city at that time. For the first time an imperial scale was mentioned for Frankfurt in 1294, because the weighing justice was mostly a privilege granted by the respective sovereign to a few selected cities, for Frankfurt , which had been imperial since 1245 , by the emperor himself. Accordingly, the scale was also used by one at the end of the 13th century served by imperial officials.

The oldest weight norms in the city are set out in a document that must be dated shortly before 1329, the job titles of the municipal officials, the wagon servants, who were probably already working in the new Libra in Affengasse, appeared for the first time in 1368 - during World War II burned - sheets on. From this it can be concluded, even without knowledge of their place of work, that the cradle justice passed to the city in the 1360s at the latest, because without that privilege it would not have been allowed to employ its subordinates in a scale belonging to the empire.

In 1502 the city council decided to build a new weighing building after the previous city weighing system could no longer fulfill its task to the satisfaction of the population for unknown reasons. For this purpose, they bought the stone house Klein-Wolkenburg next to the scales, which probably dates back to at least the 14th century, and wanted to move both of them in the summer of 1503 in favor of a new building. However, the city's plans for a larger new building at the old location did not materialize when the decision was made to sell both buildings, including the old city scales, to the Bartholomäusstift.

This time, however, it was less about the expansion of the churchyard and more about concerns about the effect of a representative urban building in the immediate vicinity of the cathedral. How important this was for the monastery is also shown by the fact that the council was not only paid 500 guilders for two houses that were undoubtedly dilapidated due to their age, but also a granary near the Metzgerpforte , a city gate on the banks of the Main at the end of Metzgergasse , left. The deal was sealed on June 1, 1503, and the monastery soon laid down the last two houses on Affengasse.

But the city's plans hadn't changed in any way: on June 6th of the same year, the building project for a “nuwe wagen huss uff den stcken der old Jewenschule” was decided in a council meeting . The workmen Hans Feltman , a carpenter , and the stonemason Wigel Sparre, who were known by name, were commissioned as municipal site managers . Even in the run-up to the contract negotiations with the monastery, the excavation of the foundations of the synagogue, which was probably a stone building, began on May 23, 1503 .

According to the handed-down construction program, the new scale building to be built should be 100 (28.46 meters) in length, the lower wall 20 (5.69 meters) high and the hall on the upper floor 16 Frankfurter Werkschuh (4.55 meters) to have. Furthermore, three wooden pillars were planned for the joists of the beamed ceiling of the ground floor hall, two entrance gates with the city's coat of arms eagles above and three attic floors as granaries. Numerous illustrations and descriptions show that the building was almost exactly designed.

With the new building, however, the synagogue had not disappeared from the cityscape either by name or architecturally: behind the city scales there was a forecourt-like wall up to the end and the so-called calf slaughterhouse on an older stone plinth, which was known as the Old Jewish School until the 19th century . This name appears again and again in house documents from the 16th to 18th centuries. Century. The forecourt-like walling, however, probably corresponded to the so-called Judenschulkirchhof .

The neighboring building Weckmarkt 3 , also New Department Store , built in 1589 at the latest and used to develop the upper floors of the Stadtwaage , was probably based on the older substance of the Jewish quarter in the form of the Jewish dance and playhouse located here. This was particularly evident in the building design, which is very unusual in Frankfurt, as a three-story solid building with a three-story roof attachment in half-timbered construction. However, this assumption is finally confirmed in the invoice items from the early 17th century, in which the cellar of the building is referred to as the “Judenbad” and thus refers to the mikveh of the previous building. In his role as Bestätteramt had to from 1590, when matched for all overland to Frankfurt goods a new import duty was levied, Report the drivers before unloading and working here Bestättern pay an appropriate fee.

Further history and use as a city archive

In contrast to the neighboring screen house, the building only served its dedicated purpose well into the 19th century. The most important imported goods such as bacon , salt or copper were weighed according to standardized weights for sale in the city on specially designed scales and a weighing fee was collected for them. In 1845, large parts of the Frankfurt City Archives , which were bursting at the seams at the time, were moved to the first floor, which required renovations and renovation measures, but did not affect the use of scales on the ground floor.

The archivists soon expressed serious concerns, since with the fat and butter scales on the first floor there were always highly flammable materials in the immediate vicinity of the valuable archival materials. They also referred to the Gothic roof structure of the building, which literally formed “a forest of wood”, and the numerous adjoining and surrounding houses, which were also largely built from the quickly combustible material.

Georg Ludwig Kriegk , who was first elected as a historian in the office of city archivist in 1863 , pointed out in the same year that, according to an external report, there was “no more unsuitable and dangerous archive” than the city scales in their current state. Finally, he applied for a complete renovation of the building, the demolition of all additions and the removal of all other offices and institutions housed there. At the same time, however, he campaigned for the building to be preserved:

“ […] It [has] its value not only in its almost five hundred year old age, but also in its beauty corresponding to the spirit of the time of its creation, which [is] far from all pretension and all unnecessary accessories, and that in connection with the cathedral and the canvas house are the only places in the city that are still medieval. "

As early as 1862, the legislative assembly of the Free City of Frankfurt demanded the construction of an independent archive building for the first time, but unsuccessfully, due to the serious structural defects of the building, which was more than 350 years old at the time. The Senate's plan, based on Kriegk's proposal, to completely renovate the city scales building to save costs while retaining its external appearance, was rejected in 1866 as still too expensive. In this context, the importance of the building in particular - contrary to the assessment of the city archivist - was rated as very low:

“ The building of the Stadtwaage [has] not the slightest artistic value, neither an architectural ornament on the facades nor any other beautiful proportions. In addition, the inner condition, namely that of the entablature, has been desolately disrupted; after the appendages have been put down [meaning the additions] there is not much left of the historical, but historically very worthless buildings. Fully functional facilities for the archive can only be achieved by completely laying down the city scales with all its appendages and erecting a new building free-standing on all sides, to be built in a simple German style and exclusively serving the purposes of the archive. "

With the annexation of the city by Prussia , the process took a back seat a few months later. For the time being, Kriegk was only able to ensure that he, his staff and scholars interested in the archive were assigned a study in the pension tower outside the city scales . The room in which important historians such as Leopold von Ranke worked was, however, constantly damp during the Main floods, which were regular at the time, and was also used by quite a hand of other municipal authorities. Nevertheless, Kriegk moved here the archival material that was considered the most valuable at the time, such as privileges , imperial letters, Reichstag files and other correspondence with the Reich.

The cathedral fire on August 15, 1867, which many Frankfurters viewed as a bad omen of the Prussian occupation of the city, was the event that heralded the beginning of the end of the old city scales. According to Kriegk's report, who was in the Libra during the fire, the building was exposed to the greatest danger since its construction:

“It was only by a miracle that the archive escaped the great danger. Had the wind not taken a westerly direction, flying fire would have penetrated the unprotected skylights, [and] within half an hour the entire interior of the building would have been destroyed by flames [...]. "

In his report, Kriegk added the expert opinion of some Prussian archive officials who described the building as "absolutely inadequate and in great need of replacement" . Under the impression of the report and the danger that the important city archive had just escaped, the decision was made in 1871 to build a new city archive at the place of the weighing machine.

End of the city scales and history to the present

In contrast to many other buildings that were disappearing at the time, no curator or historian spoke out against the demolition of the Weighing Building, except Kriegk , although its simplicity was one of the most original public achievements of the long Frankfurt Gothic and, unlike many others, had only been changed little. With the demolition in 1874 but disappeared not only the building itself, but in the sense of purifizierenden historicism and the western disclosive building on the masonry of the Jewish dance or play house that southern crops on the ruins of the old synagogue, the Jewish school cemetery and to the Libra grown Schirnen so covered resale shops. When the excavation was excavated, the Romanesque remains of the oldest synagogue were actually found , but - in accordance with the understanding of archeology and monument preservation at the time - these were not adequately documented and then removed.

The archive building, which was erected in the neo-Gothic style by master builder Franz Josef Denzinger until 1877 , looked more like a foreign body in the middle of the medieval buildings, especially since it was based on models of the splendid international Gothic , which is never so in the very conservative Frankfurt had given. Of the few, largely late Gothic components of the city scales that were secured from demolition, two coat of arms eagles were walled in on the north and south sides of the new building; a balance beam holder, a carved crucifix and a fireplace with city insignia came to the city's historical museum .

A peculiarity and old Frankfurt anecdote in connection with the new building was the legal dispute over the so-called Lautenschläger'sche Schirn , a shop that was located at the Stadtwaage. Since the owner had a very successful legal battle against the city for a long time, he was allowed to place the Schirn again in the northeast corner of the new building, where it remained for almost 15 years until the matter was finally brought to an end through a settlement and the shop disappeared.

Despite its size, the archive building was anything but adequate. The inclusion of the old holdings of the Frauenrode archive tower , which was demolished in 1900 when the new town hall was built, i.e. all the official registers kept by the city since 1311, the addition of new media such as photographs and records and the establishment of a contemporary history collection led to the fact that as early as the late 1930s The building on the Weckmarkt was literally occupied down to the last corner of the roof.

But even before Frankfurt's old town was destroyed in March 1944, the archive was badly destroyed by several direct high explosive bombs in January of the same year , which, due to neglected relocation, also resulted in the loss of one of the most valuable and complete city archives in Germany. To what extent the late Gothic coat of arms eagles used in the building and the spolia transferred to the Historical Museum in 1874 survived the destruction is still unclear today.

After the war, the plot was cleared and modernized. A residential building in the style of the 1950s, on the ground floor of which is the Café Metropol , is therefore the successor to the city archive, the city scales and the oldest Frankfurt synagogue, of which nothing on site is reminiscent.

architecture

The building, erected on a rectangular floor plan, was a solid construction made of plastered quarry stone with exposed corner blocks , architectural parts and building sculptures made of the characteristic red Main sandstone . About two by a beam ceiling with beams separate large rooms on the ground and first floors arose between the stepped gables a steep slated hipped roof with dormer rows and three attics. The late Gothic character was rounded off by the use of high cross-storey windows on the upper floor and in the first attic, while the windows on the ground floor were probably round and secured by grating from the ages.

The inner development took place through the adjoining building, New Department Store or, according to its purpose, also called Bestätteramt . It was also a three-storey solid building made of plastered quarry stone, of which only the three-storey roof attachment was made of slated timber . It is unclear how the Stadtwaage was developed in the years from 1503 to the first mention and probably also the construction of the development building in 1589. Since this, however, demonstrably (see historical part), like the city scales themselves, was based on a much older substance, and had practically the same eaves height , it can be assumed that at least the massive part existed in a form that has not been handed down at the time of construction of the weighing building and thus access to the upper part - and granted the top floors.

Shortly before it was demolished, Carl Theodor Reiffenstein , who meticulously documented and drew the changes in Frankfurt's old town in the 19th century, described in detail again on May 25, 1873:

“ The laying down of the building will begin soon, so let's re-illuminate the premises as far as possible and try to leave a clear memory for posterity in writing and pictures. From the outside, the building has an imposing character despite its simplicity and makes a very harmonious impression with the rest of the surroundings. Three eagles of stone are attached to it, two of which are on the east side and one above the portal on the north side, of the first two one is set on the corner to the south at a height of about ten feet above the ground, he is the the smallest and is on a coat of arms, but unfortunately it has been broken in a barbaric way by cutting off a piece of eagle instead of walking over it with one knee in order to make room for a standing knurl passing by. This is and remains an eternal disgrace for those officials who are entrusted with the management and supervision of the repairs to the city buildings or who were then. A fourth eagle is painted on the south side of the house above the gate, it has two small coats of arms placed diagonally opposite one another next to it, each bearing an imperial eagle. "

“Inside the building, the lower room, which takes up the whole floor, captivates our attention to the highest degree. There is no similar location here. Your ceiling rests on beams made of oak , which are extremely finely and delicately profiled and make an excellent impression. Above all, the iron balance beam holder with its graceful coats of arms is to be seen; Then in the wall we find a little cupboard, the iron door of which has a device for inserting coins and is extremely finely worked; likewise a box with a richly decorated lock plate. On the western wall, which adjoins the Bestätteramt building, which is currently being demolished, two figures are painted al fresco , on either side of a crucifix suspended from a dainty canopy , in front of which consists of an elegant base, which is also richly decorated is, a wooden beam grows out, on which there is an iron candlestick with a wooden candle. The whole thing is reminiscent of the old days and makes a good effect. Unfortunately, the top of the canopy is missing and has been added in such an unfortunate way from a drawing by Karl Ballenberger that I couldn't make up my mind to include it in my illustration. The two figures represent Saint Bartholomew and Charlemagne and seem to have been heavily restored. The entrance to this room was through the large gate on the north side; a second gate leading to the rose corner, which made the exit much easier by avoiding turning inside the building, is of more recent origin. "

Another entrance was in the wall after the Bestätteramt building, as was a door to the courtyard. The city scales were located in this room and were always besieged with barrels and bales.

“The rooms on the upper floor were accessed via the staircase in the adjoining Bestätteramt building, which in any case owes its emergence to a later time, as from the intersections of the bars on the door, which has been broken through the western gable wall and to which it leads is seen. Probably this institution was only built around the middle of the 17th century. Century. On the first floor, which contains a very spacious room, a large part of the files of the city archives is housed. A large fireplace arouses our lively interest here, which, despite its simplicity, is tastefully and excellently executed in stone and bears two eagles on its main front, but which have been so often painted over with paint over the years that they have lost all sharpness and clarity and can hardly be seen anymore. Here one becomes even more aware of the dilapidation and one does not really understand that the building did not collapse long ago in this neglect. Convinced and satisfied of the need to demolish this simple and beautiful monument to a rich past, we leave the room, inspired by the wish that it may be possible to replace it with a worthy new building. In any case, Frankfurt is getting poorer by a characteristic monument of its prehistoric times, which is all the more difficult as it has extremely little to lose in this respect. "

literature

- Affengasse . In: Johann Georg Battonn : Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volume III. Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1863, pp. 323–331 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive )

- Wake-up market . In: Johann Georg Battonn: Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volume IV. Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1864, pp. 1–3 u. 15–19 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive )

- Rudolf Jung , Carl Wolff : The architectural monuments in Frankfurt am Main . Second volume. Secular buildings . Völker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, p. 295-300 ( digital copy [PDF]).

- Otto Ruppersberg: The history of the archive building on the Weckmarkt. On the fiftieth anniversary of the day of its completion on February 18, 1929. In: Alt-Frankfurt. Quarterly for its history and art. 2nd year, issue 3, Frankonia Verlag und Druckerei, Frankfurt am Main 1929, pp. 32–35.

Web links

- Canvas house & city scales. altfrankfurt.com

References and comments

- ^ Johann Friedrich Boehmer, Friedrich Lau: Document book of the imperial city of Frankfurt . J. Baer & Co, Frankfurt am Main 1901–1905, Volume I, pp. 262, 263, Certificate No. 544, May 25, 1288.

- ^ Christian Ludwig Thomas: The excavations in the cathedral courtyard and on the Weckmarkt in 1896 and 1897 . In: Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art. Third episode. Sixth volume . K. Th. Völcker's Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1899, pp. 314-322.

- ↑ Until the move to Judengasse in 1462, the Frankfurt Jews were free to choose their place of residence. In comparison with other imperial cities such as For example, in Cologne or Regensburg at that time, this was extraordinarily liberal, there was a ghetto there, which was even closed by the city every evening and every morning, which the city also paid for; see. on this: Isidor Kracauer: History of the Frankfurt Jews in the Middle Ages. From the internal history of the Jews of Frankfurt in the 14th century (Judengasse, trade and other professions) . Verlag von J. Kauffmann, Frankfurt am Main 1914, p. 7.

- ↑ Johann Georg Battonn: Slave Narratives Frankfurt - Volume III . Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1863, pp. 328–331; Comments on the Alte Judengasse.

- ↑ Battonn III, pp. 239-250; Remarks on the churchyard before 1537.

- ↑ Kracauer, p. 6; according to the excavation findings by Christian Ludwig Thomas on the Weckmarkt in 1897, on which the map shown is based.

- ↑ Battonn III, p. 323; Comments on the Affengasse.

- ↑ Johann Georg Battonn: Slave Narratives Frankfurt - Volume IV . Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1864, p. 11; Quotation from the manuscript: "OU 1360. Der Juden Spielehaus at the Judenschul zu Frankfurt" , 1390 and 1405 it is mentioned in interest books of the Bartholomäusstift as "domui corearum judeorum" .

- ^ Rudolf Jung, Carl Wolff: The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main - Volume 1, Church buildings . Selbstverlag / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1896, p. 363; here quote a Jewish source of 1241: "[...] the holy synagogue was destroyed, villains invaded, plundered and looted and torn in their fury share our beautiful, magnificent laws roles." .

- ↑ a b Kracauer, p. 24 u. Jung, Wolff, Vol. 1, p. 363; When the Stadtwaage and its back building were demolished, the remains of what was probably the first synagogue were found in Romanesque forms, in the sense of the Frankfurt style sequence, i.e. at least from the first half of the 13th century. In addition to a round arched window, the foundation walls of a Romanesque basilica with a round apse were exposed for the legal ark. The find was inadequately documented, let alone archaeologically, and apparently completely removed for the foundation of the successor building.

- ^ Richard Froning: Frankfurt chronicles and annalistic records of the Middle Ages . Verlag Carl Jügel, Frankfurt am Main 1884, p. 8; A text probably written down at the beginning of the 16th century from the second half of the 15th century, which in turn is based on eyewitness reports (Baldemar von Peterweil?) from the 14th century, but in the overall context represents more of a plenum for the resettlement of the Judengasse that took place at that time. Some passages are still a valuable source for the sparse traditional conditions here for the destruction level of the year 1349: "stantibus in cimiterio ejusdem Basilice liberum ad pontine medium prebuerunt aspectum." This accordingly means in German: "From the cemetery [cemetery] offered a unobstructed view to the middle of the bridge [old bridge]. "

- ↑ Kracauer pp. 13-15; By pledging the Jewish residence for 15,200 pounds of Heller under a contract with Emperor Charles IV on June 25, 1349, the ownership of the Jews was transferred to the city. A clause in the contract also automatically made her the heir to the owners of deceased or killed Jews. Due to great desires for the land - u. a. on the part of the Augustinian order and the then Lord von Hanau, Ulrich III. - the rubble on it was only cleared in 1357, and in this context the synagogue was also explicitly mentioned, which was apparently burned out and full of ruins.

- ↑ Kracauer, p. 18; only from the 1380s onwards could it be proven that Jews were homeowners again.

- ^ A b Roland Hoede, Dieter Skala, Patricia Stahl (ed.): Bridge between the peoples - On the history of the Frankfurt fair. Volume III: Exhibition on the history of the Frankfurt trade fair . Union Druckerei und Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-89282-021-X , p. 65.

- ↑ Battonn III, p. 326; Quotation from the manuscript: "Stadt-Rechenbuch de 1372. A Wagehaus was built that year." , 1388 there is another mention in the record of the jury.

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 6 and 7; here are extracts from the Liber censuum with precise descriptions of the three houses as Domus stral Judaei , Domus dicti Physis Judaei and Domus dicta zu der Schalin .

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 18; Battonn claims to have seen the heraldic eagle painted on the preserved rear building of the city scales in the 18th century.

- ^ Karl books, Benno Schmidt (ed.): Frankfurt official and guild documents up to the year 1612. Second part: official documents . In: Publications of the Historical Commission of the City of Frankfurt aM . VI., Joseph Baer & Co, Frankfurt am Main 1914–1915, p. 288, reference to the document with the signature Ugb B, 95 no. 32 p. 4.

- ^ Karl books: The professions of the city of Frankfurt aM in the Middle Ages . In: Treatises of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences in Leipzig. Philological-historical class . XXX. Volume, No. III, BG Teubner, Leipzig 1914, p. 128; Reference to Bedebuch Ni. 9a from 1368–1371 with the excerpt "Clawes, the knecht zur dare" .

- ↑ Battonn III, p. 324; The house name is probably a vernacular corruption of Stein Wolkenburg , which already indicates that the building was a domus lapidea , i.e. a stone house. It was first described in great detail by Baldemar von Peterweil in his Liber redituum in its urban planning position in 1350 . According to another documented source from Battonn, the building was the house of Henricus de Wolkenburg , who died in 1332 and was a vicar of the Bartholomew Stift. Such an important person would at least be a logical explanation for a stone house at that time otherwise only reserved for the high nobility.

- ^ A b Rudolf Jung, Carl Wolff: Die Baudenkmäler von Frankfurt am Main - Volume 2, Secular Buildings . Self-published / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1898, p. 295.

- ↑ Battonn III, pp. 324-327.

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 18; Quote from the manuscript: “ Stdt. Rchnbch. 1503. The city has the new Wagenhuss built by its Buwenmeister and feria 3tia post vocem jucunditatis 1513 [probably a transcription error, that is certainly 1503] the foundation stone is laid in the old Jewish school next to the Garnehuss council respect. the foundation raised to dig. ".

- ↑ 1 Frankfurt factory shoe corresponds to 28.461 cm.

- ↑ Jung, Wolff, Vol. 2, p. 295 and 296.

- ^ Battonn IV, p. 19.

- ↑ Battonn IV, p. 16; Quote from the manuscript: “1336. The Judenschulkirchhof zu F. “ .

- ↑ Battonn IV, pp. 3 and 4; the new department store appeared in the accounting books for the first time in 1589 as a revenue item that was then updated annually. On the mikveh in the cellar Quote from the manuscript: “1613. The city draws interest (rent) from the cellar, called the Judenbad, under the new department store (modo canvas house) à fl. 6, […] ” .

- ^ Hans Otto Schembs: Frankfurt archive. Volume 1 . Archiv-Verlag Braunschweig, Braunschweig 1982, p. F 01050.

- ↑ a b c Jung, Wolff, Vol. 2, p. 296.

- ↑ Otto Ruppersberg: The history of the archive building on the Weckmarkt. On the fiftieth anniversary of its completion on February 18, 1929 . In: Alt-Frankfurt. Quarterly for its history and art . 2nd year, issue 3, Frankonia Verlag und Druckerei, Frankfurt am Main 1929, p. 33.

- ↑ a b Ruppersberg, p. 34.

- ↑ a b c Ruppersberg, p. 35.

- ^ Franz Rittweger, Carl Friedrich Fay (Ill.): Pictures from the old Frankfurt am Main. According to nature . Publishing house by Carl Friedrich Fay, Frankfurt am Main 1896–1911; according to the caption by Franz Rittweger on the city scales.

- ↑ Jung, Wolff, Vol. 2, pp. 297-300; after Reiffenstein's manuscript printed here.

- ↑ Jung, Wolff, Volume 2, p. 298; Footnote: “The eagle is not painted, but made of stone, the little coats of arms are not above, but below; [...] ".

- ↑ Jung, Wolff, Volume 2, p. 299; Footnote: "From the year 1831.".

Coordinates: 50 ° 6 ′ 36.6 ″ N , 8 ° 41 ′ 8.2 ″ E