Mills in Leipzig

Since the Middle Ages are mills in Leipzig proved. They were watermills, and they were all west of and near the city. The process water was brought in through mill ditches from the flood-prone floodplain area of Pleiße and Weißer Elster . Since water power was the most important source of energy until the 19th century, the mills were not only used as grain mills, but also to drive various other trades. In addition, the regulation of the weirs and ditches and their maintenance also provided a certain level of flood protection.

The most important mills from south to north were the nuns -, the Thomas -, the barefoot - and the Angermühle . The Leipzig children learned their names with the slogan: " Thomas went barefoot with a nun over an Anger ". Because of the low gradient of the rivers in the Leipzig area, all mills had undershot water wheels. The mills were in operation until the end of the 19th century and in one case even beyond, although they were already located within the urban area after the town grew.

With the incorporation of the surrounding villages, more mills came to the city, but most of them are no longer in operation either. Until the abolition of the compulsory meal and the introduction of the freedom of trade (in Saxony in 1838 and 1861), the milling trade remained strictly regulated. The mills initially belonged to the respective landlords. This could be landowners or monasteries (Angermühle, Nonnenmühle), but also the township. While the Mühlbann protected the catchment area of a mill by prohibiting the construction of further mills in the area in question, the grinding compulsion obliged farmers to have their grain ground in a specific mill.

There were also numerous windmills in Leipzig, and particularly in the incorporated areas .

Historic mills in the old city area

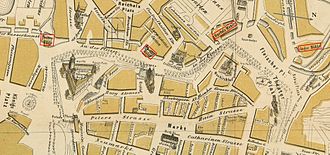

Barefoot mill

The barefoot mill (also castle or barefoot mill) was created in connection with the Libzi Castle, which was built in the 10th century on the neighboring hill that later supported the Matthäikirche . ( Map ) It should have been the oldest mill in Leipzig. A mill ditch was created for their operation, which branched off from the Pleißen's course in the southern third of today's Friedrich-Ebert-Straße (Kuhstrangwehr weir), and then flows north of the mill into the Parthe .

In 1224 the castle was razed and a Franciscan monastery was built on its site . Since the Franciscans were also called barefoot, the name barefoot or barefoot mill became common for the neighboring mill, although the mill never belonged to the monastery. Rather, Margrave von Landsberg Friedrich (the Stammler) gave the mill, including the neighboring Naundörfchen, to the Clariss Monastery of Seusslitz near Meißen . In 1550 the mill came to the City Council of Leipzig, which had it completely rebuilt in 1592. After a repair in 1656, it received its final shape in 1703.

From 1818 to 1827, Johann Christian Gottlieb Irmler's pianoforte manufacture was also based in the barefoot mill. The mill was privatized in 1851. In 1876, the company FA Sieglitz & Co. set up a tobacco dye factory for dressing and dyeing fur skins. Due to a lack of space and because of "excess anger" with the neighbors - the tanning of skins is associated with unpleasant smells - they soon moved to Plagwitz . In 1897 the Leipziger Bauverein bought the barefoot mill and had it demolished in 1898. The mill moat was vaulted. The main building of the Leipzig Life Insurance Company ( Alte Leipziger ) was built on the property in 1907/1908 . This building has been used by the "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" University of Music and Theater in Leipzig since 2002 .

Angermühle

The Angermühle was initially called Jacobsmühle and was first mentioned in 1165. It got its name after the Jacobskirche opposite. After this was demolished in 1544, the name Angermühle became common. The Angermühle was located on the Elstermühlgraben built for its operation, which was branched off from the former two Elster arms by two weirs (Steinernes and Hochzeit weir), roughly on today's property at Jacobstrasse 1. ( Map )

The mill belonged to the Augustinian monastery of St. Thomas , which it sold in 1296. It was then privately owned until the city of Leipzig acquired it in 1499. It is believed that with this sale, papermaking ceased. The mill was mainly used as a flour mill, but also as a spice, oil and tobacco mill. In its heyday it had ten water wheels, spread over two grinding buildings on either side of the mill ditch. The first paper was produced here in Leipzig in 1492. A municipal brewery also belonged to the mill, in which the council housed its mint in the 17th century . The mill was renewed several times after fires and dilapidation.

After the piping of the Elstermühlgraben in the course of the expansion of the Ranstätter Steinweg, the Angermühle was demolished in 1879. A mill tablet from 1701 has been preserved on the house at Jacobstrasse 1.

When the geographer and polymath Johann Gottfried Gregorii alias MELISSANTES published a fabulous story about Faust's infernal compulsion in the Angermühle in Leipzig , the mill was given a literary monument as early as 1712. As a popular fist fabric, the legend was adopted in several legends of the 19th century.

Thomas Mill

The Thomasmühle was about 250 meters southeast of the barefoot mill on the site of today's new building Dittrichring 5–7 on the reopened Pleißemühlgraben ( map ). The mill was named after the St. Thomas Church opposite it in the old town of the former Augustinian monastery of St. Thomas . But at no time was it owned by the monastery. Although it was probably built around 1200, it was first mentioned in a document in 1287.

In order to operate the Thomasmühle, the water flow in the Pleißemühlgraben was reinforced by a weir further south, so that at normal water level all the water in the Pleiße now flowed through the Mühlgraben. As a result, the Mühlgraben took on the name Pleiße until the 19th century. After a fire in the Thirty Years War in 1642, the mill was rebuilt.

The Thomasmühle had changing owners. In 1832 it was leased by Johann Gottlieb Schlobach, who bought the mill in 1845. Schlobach's son Franz Schlobach wanted to set up a sawmill and veneer factory, but eventually founded it in 1846 under the name Franz Schlobach Säge- und Veneierwerke in the Böhlitz grain and oil mill in Böhlitz-Ehrenberg, which had been in existence since the 13th century, and leased the Thomasmühle to Franz in 1885 Lucke (1857–1927), who later acquired the mills in Knauthain, Knautkleeberg and Stahmeln. With Schlobach's approval, Lucke installed a steam engine in 1887 and an electric dynamo in 1893 to illuminate the mill. On July 1, 1897, Paul Georg Otto Schlobach, grandson of Johann Gottlieb Schlobach and the last owner of the Thomasmühle, sold the property and the adjacent land to the city, which continued the lease with Lucke. After the modernization of the turbine system, the mill was in operation until it was destroyed in World War II. The turbine wheel was recovered during construction work in 1995 and is exhibited on the Dölitzer Mühle site (see below).

Nun mill

Before 1230 a Cistercian convent was moved from Hohenlohe to Leipzig. In 1241 the nuns of this Georgen monastery received the mill of the village of Lusitz south of Leipzig from Margrave Heinrich von Meißen . But they gave up this as early as 1287 and built a new mill, the Nonnenmühle, in the immediate vicinity of their monastery on today's Karl-Tauchnitz Bridge. ( Map ) For the nuns mill, a new piece of mill ditch was created with the Pleisse drain further south and the underwater of the mill was integrated into the existing mill ditch. This is how the course that roughly corresponds to today's Pleißemühlgraben was created.

After the introduction of the Reformation, the mill came to the city together with the monastery in 1543. After destruction in both the Schmalkaldic and the Thirty Years' War, the mill was rebuilt. From the middle of the 19th century, cardboard, bookbinding cardboard and roofing felt were also produced in the Nonnenmühle. A bathing establishment was set up in the underwater of the mill. The mill was demolished in 1890 with the construction of Karl-Tauchnitz-Strasse and -brücke.

The nearby Nonnenmühlgasse and a small installation of water wheels in the reopened Pleißemühlgraben at the site of the mill are still reminiscent of the mill.

Polishing mill

In 1454 the city council hired an armorer to repair and maintain its armor , armor and equipment . This required a polishing device , which was usually driven by a water wheel. Since the city of Leipzig did not yet have its own mill and the construction of another mill at the Mühlgräben was not possible, a ship mill was stationed in the Pleißemühlgraben near the bridge over the Ranstädter Steinweg . ( Map ) After it was damaged by a flood in 1683, the mill was not rebuilt, as polishing facilities were now in place in the Anger and Barefoot Mills, which now belonged to the town.

Horse mill

Leipzig also had a mill that was neither driven by water nor wind until the 19th century. A horse peg provided the driving force and thus the name "Rossmühle". It was on Eselsplatz across from the University's Small College . ( Map ) Eselsplatz was later called Ritterplatz and is now the junction from Ritterstrasse to Goethestrasse. It is believed that the name Eselsplatz can be traced back to the animals waiting to transport the grain or flour sacks to and from the area. On a Leipzig city map from 1757 the mill is listed as "moulin a chevaux" (horse mill).

The building complex with the Rossmühle had to give way to the construction of the Georgenhalle at the beginning of the second half of the 19th century .

Mills in later incorporated districts

At the Pleiße

The three villages of Dölitz , Lößnig and Connewitz , located on the eastern edge of the Pleißenaue, worked together between 1200 and 1250 to create a mill ditch, today's Mühlpleiße . Each of the villages or manors ran a mill on it.

- The Dölitzer mill ( map ) was first mentioned in a document in 1540. In 1646 it was renewed by the owner of the Dölitz manor, Georg Winckler . In the Battle of Nations on October 18, 1813, it burned to the ground, but was rebuilt the next year. In 1870 it was powered by a turbine and was then modernized several times. It was shut down from 1920 to 1950 and before its final shutdown in 1974 worked as a grist mill for a feed mill. It still has partially preserved mill technology and is the last preserved watermill in Leipzig to be listed as a historical monument. A non-profit association has been dedicated to maintaining the mill and the mill yard since 1992. Since 2009 a newly built mill wheel has been generating 5 kW of electrical energy via a generator system, which is fed into the public grid.

- The Loessnig mill ( map ) belonged to the Loessnig manor. It was destroyed in 1813, but rebuilt in 1815. In 1850 the mill was converted into a paper mill. This burned down in 1852. In 1890, the two Limburg villas on Mühlpleiße were built on the former mill site.

- The Connewitz mill ( map ) came into the feudal lordship of the Bishop of Merseburg as early as 1275 through a donation from Margrave Dietrich von Landsberg , who in the following year transferred all rights to the Augustinian Canons' Monastery, which from 1277 also owned the Connewitz manor. In 1459 a copper hammer and a grinder were added to the grinding, oil and spice mill . In 1679 the City Council of Leipzig bought the mill, to which a cutting mill was now attached. While this ceased operations in 1903, the grinding mill worked until it was destroyed in World War II. There is now a car dealership on the former mill site at the entrance to Mühlholzgasse.

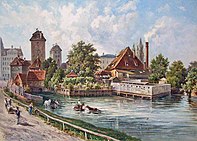

At the White Elster

The Elstermühlgraben between Profen and Großzschocher , which was 29 kilometers long before it was interrupted by lignite mining , was created in the 12th century by the monks of Pegau monastery and at the instigation of Wiprecht von Groitzsch and rebuilt in 1627. Of the eleven mills operated on it, today's Leipzig area includes those in Knauthain , Knautkleeberg and Großzschocher.

- The Knauthainer mill ( map ) was built as a water mill in the 12th century. It was first mentioned in 1417 as an oil mill. The “Mahl- und Oelmühle” went to Karl-Hildebrand von Dieskau by inheritance in 1706. In 1820 a new grain mill was built, and between 1908 and 1910 the mill at Am Mühlgraben 14 was built as a large, modern operation. In the mill, which was sold by Franz Pauli to Franz Lucke in the 1920s, only wheat was processed from 1933 onwards. From 1947 oat flakes were produced in an outbuilding. After the plant was closed, the wheat mill was put up for sale in 1991. A community of six-party builders built individual lofts in it based on a owner-occupier model. The project was awarded the Hieronymus Lotter Prize for Monument Preservation by the City of Leipzig.

- The Knautkleeberg art mill ( map ) at the corner of Seumestrasse on the corner of Am krummen Graben was last designed by Wilhelm Festner in 1867/68. In 1875 a warehouse building was built in place of a barn. The house on Seumestrasse was rebuilt in 1885 after the old one was demolished. After a fire-related rebuilding, the mill was reopened on August 28, 1900. Later it passed into the possession of Franz Lucke and was last operated as a rye mill. The Vierseithof, which has not been used since the 1990s and includes the mill, was converted into a residential complex with 26 apartments in 2008-2012.

- The Großzschocher mill ( map ) was built by the manor in the 12th century. Benno Pflugk sold the water mill, which had two weirs in the Elster, to Gregor Seiler in 1568, until it was bought back for the estate by Bruno and Otto von Dieskau in 1658 . Under the direction of the leaseholder and mill builder Johann Balthasar Breitschuh († 1731), the old water mill was demolished in 1705 and a new, fairly fireproof mill with 6 grinding cycles was built. The later owner, Friedrich Wilhelm Kabitzsch, was the first large miller in Germany to abolish the wage system in 1840, so that he could sell the flour from the grain he had bought on his own account. On January 1, 1865, the elder of the community Großzschocher Anton Leberecht Zickmantel (1838–1901) - in 1905 a street in Großzschocher was named after him - first shares in the mill from the previous owner J. Eberius. July 1869 for 108,000 thalers together with Friedrich Schmidt (1838-1897) the whole mill, which now operated as Zickmantel & Schmidt . Both replaced the water wheels with turbines, later supported by steam engines; In the immediate vicinity a gas works, a forge, a locksmith's shop, a sheep farm and a mill park were built, and the mill developed into one of the largest and most modern mills in Saxony. After severe bomb damage on February 20, 1944, the LPG " Florian Geyer " later took over the property and used it as a warehouse and for breeding chickens. The 5000 m 2 area, which has been vacant since the beginning of the 1990s, is to be converted into 25 condominiums by 2014, with the remaining technical installations remaining visible.

After the Elster had passed near Leipzig city center, further mills followed in the northeast of the city, for example in Wahren , Stahmeln , Lützschena and Hänichen . There was no common long mill ditch here, but the mills had their own short ones or were located directly on the river and regulated the water level via a ditch.

- The building of the no longer operated Wahren mill ( map ) is still standing.

- The mill in Stahmeln ( map ) is the only mill on the White Elster that is still working today. It was first mentioned in an interest register in 1486. In 1647 it burned down completely, in 1661 it passed into the possession of Rudolph Siegmund Fuchs. After another fire in 1875, two turbines were installed instead of a water wheel and most of the millstone grinders were replaced by roller mills. In 1893 Franz Lucke (1857–1927) bought the mill and gradually expanded it. Among other things, a steam engine was installed and the turbines were replaced to operate the mill even in drought and flood conditions. In 1896 the house belonging to the mill was demolished and replaced by an office building, and a new factory owner's villa was built at Mühlenstrasse 17. The Obermüllerhaus Am Anger also belongs to the mill. Until the conversion in 1905 and the associated new construction of a five-storey cleaning building, the mill supplied the garrison on the Pleißenburg as a food mill for the army . After the demolition of most of the buildings, the complex that characterizes the Stahmelner townscape today was rebuilt in 1912 according to the design by Max Woldemar Vogel from Leipzig and the technical equipment of the nurse, Giesecke & Konegen AG Braunschweig. New roller mills , elevators , plansifters and cleaning machines were installed, the grain silo enlarged and the flour storage area expanded. The machine units were also equipped with an electric motor drive. Since during the First World War the Reichsgetreidstelle required the storage of large quantities of grain, the mill was given an eight-story, 35-meter-high grain silo in 1916/17. In 1934/35, a six-part steel silo with a capacity of 1500 tons was built on its concrete foundation. The distinctive shape of the silo, which is equipped with a drying and areginal gasification system, dominates the entire mill area. During the Nazi era, the Kunstmühlen-Werke Franz Lucke were a National Socialist model company . After the Second World War, the mills now managed in trust were considered to be the second largest mills in Saxony.

- The mill in Lützschena, which initially belonged to the manor ( map ), is reported to have caught fire during acts of war in 1547, but was rebuilt. The mill property was rebuilt in 1796–1800. Today a hydropower plant is operated on the site of the mill.

- The water rights of the mill in Hänichen ( map ) can be traced back to the 15th century. In 1921 it was rebuilt after a fire and in 1925 it went to the Stern bread factory in Leipzig-Eutritzsch. From 1980 to 1991 the mill served as a residence for foreigners. Today a hydropower plant works here.

On the Parthe

Although the Parthe is not nearly as rich in water as Pleiße and Elster, mills were also operated on it. In what is now Leipzig's urban area, these were those in Portitz , Thekla and Schönefeld . From the Portitzer mill ( map ) and the Theklaer mill ( map ) nothing is left today. Due to river straightening, some of the former mill locations are no longer on the river.

- The Schönefeld watermill ( map ) was already there when Schönefeld was first mentioned in 1278. Like the Schönefeld Castle and the church, it was destroyed and rebuilt several times. Due to the straightening of the Parthe, operations were stopped in 1928, but the building continued to be used commercially. On May 20, 2006, a thunderstorm set fire to the roof structure of the mill building at Ossietzkystraße 70. The fire damage was repaired, but the building is currently unused.

- The mill in Gohlis ( map ) was often described as being located on the Pleiße, since with the introduction of the Pleißemühlgraben into the Parthe (see above), its end was temporarily referred to as the Pleiße. Still, strictly speaking, it was down to the Parthe. The mill was first mentioned in 1390. In 1877 the mill building was rebuilt again, before the mill lost its water connection due to river regulations between 1905 and 1913 and the mill was shut down in 1908. In the house belonging to the mill, an inn was operated during and after the mill. After the buildings fell into disrepair after 1990, the facility has been extensively renovated since 2011. It houses a daycare center, offices and a restaurant in the former mill building.

To Luppe and Zschampert

None of the former mills at Luppe and Zschampert are still in operation.

- The mill in Lindenau ( map ) on the Luppe, first mentioned in 1448 (today after hydraulic engineering measures, Kleine Luppe ) was initially a fulling mill. On May 18, 1553, it was bought by Johann Schaffhirt for 1000 guilders and converted into a paper mill. Johann Schaffhirt is the brother of Hieronymus Schaffhirt and was born around 1522. Then unfortunately he got problems with the installment payments and his father Michael took over for a short time in 1556. Michael died that same year. On November 12, 1558, Johann Schaffhirt and his wife sold the paper mill to the City Council of Leipzig for 750 guilders. Johann went back to Dresden and in 1559 bought a piece of land in Aussig to build a paper mill. The building was later converted into a flour mill, destroyed in the Thirty Years War and only rebuilt in 1710. During his retreat, Emperor Napoleon stayed briefly in the Lindenauer Mühle on October 19, 1813. In 1920 the Lindenauer mill burned down.

- The mills in Böhlitz ( map ) and Gundorf ( map ) were both located on a mill ditch branched off from the former Luppe. After the expansion of the Neue Luppe in the 1930s, it was no longer possible to operate a mill on the now arid river.

- The mill in Rückmarsdorf ( map ) was operated at the outlet of a small pond that was fed by a mill ditch branched off from the Zschampert stream .

Windmills

The oldest mentioned windmills near the city were roughly at today's Bayrischer Platz. They were already destroyed during the Thirty Years War . Memory of it lives in the Windmühlenstraße leading there.

There were many windmills in the villages around Leipzig that were later incorporated. For example, 35 windmills are recorded on the Royal General Staff maps from 1879 in the area that is now the city of Leipzig. They were particularly found in areas without sufficient running water and in wind-exposed locations east and north of the city.

The mills were not only used to grind grain. Examples are the Quandtsche Tabaksmühle in Thonberg ( map ) and the paper mill in Stötteritz ( map ). In the tobacco mill, which was destroyed during the Battle of the Nations, tobacco was ground to make snuff. In the paper mill built in 1801, rags were processed into brown wrapping paper from 1803 . It burned down in 1810. Street names in Leipzig still remind of both mills.

Very little remains of the Leipzig windmills. Those close to the city had to give way to urban expansion at the end of the 19th century. At the place of the Kleinzschocher windmill ( map ), the development around the Gießerplatz began in 1890 . The Eutritzsch windmill ( map ) disappeared in 1889. The Schönefeld windmill ( map ), which was built as a post mill in 1712, lasted the longest in the vicinity of the city - until 1910 . From 1841 to 1860 it was owned by the amateur meteorologist Friedrich Wilhelm Stannebein .

Finally, the electric mill drive put an end to the windmills. Remains of windmills in Leipzig can still be found in Knautnaundorf ( map ) as a brick housing, in Lindenthal ( map ) and in Holzhausen ( map ) with wings and in Göbschelwitz ( map ) only as a foundation. The Knauthainer windmill, built in 1878 on Rehbacher Strasse ( map ), worked with wind until 1954. With an electric drive, it has only supplied the feed trade since 1992.

literature

- Horst Riedel: Stadtlexikon Leipzig from A to Z. PRO LEIPZIG, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-936508-03-8 , pp. 414-416.

- Georg Grebenstein: The Leipzig waters from the turn of the millennium to the present. In: New Shores. Volume 3, Stadt-Kultur-Projekt Leipzig, Leipzig 1995.

- Pro Leipzig e. V. (Ed.): In Leipziger Pleißeland. Connewitz, Loessnig, Dölitz. Passage-Verlag, Leipzig 1996, ISBN 3-9804313-4-7 .

- Pro Leipzig e. V. (Ed.): In the Leipziger Elsterland. Plagwitz, Schleußig, Kleinzschocher, Großzschocher, Windorf, Knautkleeberg, Knauthain, Hartmannsdorf. Leipzig 1997, ISBN 3-9805368-3-1

- Topographic maps (equidistant maps) of Saxony, processed in the topographic bureau of the Royal General Staff. - 1: 25000. - 156 sheets, various editions 1874–1918. Giesecke & Devrient, Leipzig, online at Deutsche Fotothek (for the localization of the historic mills)

Individual evidence

- ^ Exhibition water in Leipzig. New Shore July 2004

- ↑ Grebenstein, Neue Ufer 3, p. 10

- ^ Walter Fellmann: The Leipziger Brühl . VEB Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1989, p. 100.

- ↑ The Jacobs or Angermühle in Leipzig encyclopedia

- ^ Jacobskirche in the Leipzig Lexicon

- ^ MELISSANTES, The curieuse and learned HISTORICUS ..., Frankfurt, Leipzig [and Erfurt] 1712, pp. 850 ff.

- ↑ Turbine wheel in the Dölitz mill area

- ↑ Äußere Südvorstadt , Pro Leipzig 1998, p. 4

- ↑ Grebenstein, Neue Ufer 3, p. 18

- ↑ Gina Klank, Gernot Griebsch: Lexikon Leipziger Straßeennamen , Verlag im Wissenschaftszentrum Leipzig, 1995, ISBN 3-930433-09-5 , p. 179

- ^ Plan de Leipzig 1757, digitized in the SLUB

- ^ Dölitz watermill

- ↑ Picture of the Connewitz mill from the street side around 1920 here

- ↑ Wheat mill Knauthain

- ↑ Knautkleeberger Mühle residential complex

- ↑ Heinrich Engelbert Schwartze: Historical gleanings of the stories of the city of Leipzig, especially of the surrounding area and landscape, as associated with excellent knights' seats, gentlemen, pastors / scholars and remarkable incidents [...] August Stopffeln, Leipzig 1744, p. 55

- ↑ Renaming of streets. Decision III-496/00 of December 6, 2000. In: Leipzig Official Journal , No. 26 of December 23, 2000

- ↑ Gina Klank, Gernot Griebsch: Lexicon of Leipzig street names. Verlag im Wissenschaftszentrum Leipzig, 1995, ISBN 3-930433-09-5 , p. 45.

- ^ Alfred Möbius: Pictures from Großzschocher's past. History of the villages Großzschocher-Windorf. (Reprint of the original edition, Schalscha-Ehrenfeld, Leipzig 1906), Pro Leipzig, Leipzig 1999, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Jens Rometsch: The mill in Großzschocher is being renovated. In: Leipziger Volkszeitung of December 28, 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Lützschena-Stahmeln website (history and face - call up the Elstermühlen)

- ↑ Stamen. A historical and urban study. Pro Leipzig, Leipzig 2000.

- ^ German Historical Museum , object database: Franz Lucke

- ^ Chronicle Leipzig-Lindenau

- ↑ Gina Klank, Gernoth Griebsch: Encyclopedia Leipziger street names . Ed .: City Archives Leipzig. 1st edition. Verlag im Wissenschaftszentrum Leipzig, Leipzig 1995, ISBN 3-930433-09-5 , p. 224 .

- ^ Topographic maps (equidistant maps) Saxony