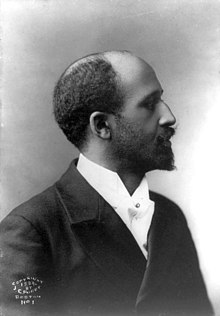

WEB you Bois

William Edward Burghardt "WEB" Du Bois ([duːˈbɔɪz], born February 23, 1868 in Great Barrington , Massachusetts , † August 27, 1963 in Accra , Ghana ) was an American sociologist , philosopher and journalist who participated in the Civil Rights Movement .

Live and act

Du Bois came from a black family in Massachusetts who had been free for many generations and had risen to the middle class at an early age. On the maternal side, the family can be traced back to free people before the Revolutionary Wars, and on the father's side to immigrant Haitian blacks , whose former slave owner was a French Huguenot . The family name Du Bois has its origin here.

From 1883 he worked as a journalist and studied alongside. In 1885 he earned a bachelor's degree and worked until 1888 as a teacher at a rural school in Tennessee . In 1888 he continued his studies at Harvard , where he earned a Masters in History in 1892 and won the Slater Foreign Scholarship. From 1892 to 1894 he studied in Germany at universities in Berlin and Heidelberg .

In Heidelberg he attended lectures with Max Weber , in Berlin with Gustav von Schmoller and Heinrich von Treitschke . In his autobiography he spoke of a broadening of horizons in the German capital: “There were white people - students, friends, teachers - who experienced the present with me. They didn't see me as an abnormality or as subhuman. I was just a slightly more privileged student whom they were happy to meet and with whom they could talk about God and the world, especially the world I came from. ”Du Bois also found his great admiration for in Berlin the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck : “He formed a nation from a mass of quarreling peoples. [...] This gave me an inkling of what American blacks must do: march ahead with strength and determination under capable leadership. "

On his return he was the first black man to obtain a doctorate from Harvard in 1895; his subject was the transatlantic slave trade . Despite receiving top grades, he was denied an academic career at renowned universities, and in 1895 he accepted a teaching position at Wilberforce College in Ohio . A year later he got a research assignment in Philadelphia , but the teaching was denied him. With the publication of his research on the situation of blacks in Philadelphia, he achieved his scientific breakthrough as the first black sociologist.

From 1897 to 1910 he held a professorship for history and economics at the black University of Atlanta , which he used for further studies on the situation of the black population, especially in rural areas. At the same time he published a number of articles and founded several newspapers. During the year 1900 he participated in the first Pan-African Conference in London in part and became famous for his proclamation To the Nations of the World ". The trouble of the twentieth century is the problem-of the color line" with color line is meant the race barrier. The proclamation was addressed directly to the British government and called for the judgment of people on the basis of their physical condition to be overcome: "Let not more color or race be a feature of distinction drawn between white and black men, regardless of worth or ability."

Du Bois was involved in the emerging civil rights movement , but broke with the views represented by Marcus Garvey , among others , that black people could only be emancipated in their own state or by returning to Africa . Rejecting Booker T. Washington’s view that blacks should seek to improve their social status primarily through training and adjustment, Du Bois and others founded a movement in 1905 calling for full civil liberties for all blacks and an end to discrimination. It was called the Niagara Movement after the first meeting point .

In his main work The Souls of Black Folk (1903), which is influenced by German classical music and the psychology of the peoples of Herders and Nietzsche , Du Bois describes the psychological and social consequences of the fact that the identity of blacks is defined by others and made a problem. He declares black music - especially Negro Spirituals in the contemporary context - to be the “unique spiritual heritage of the nation” and the “greatest gift of the Negro people”. Max Weber was impressed by this work and began correspondence with Du Bois. He suggested a German translation (which did not materialize) and won Du Bois for a contribution to the Archives for Social Science and Social Policy : The Negro Question in the United States . In 1909 Du Bois became a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an institution of the anti-racist civil rights movement that still exists today. From 1910 to 1934 he was a member of the board of directors of the NAACP and editor of the association's magazine The Crisis , in which important representatives of the Harlem Renaissance such as Claude McKay , Jean Toomer , Nella Larsen , Georgia Douglas Johnson , Countee Cullen , George Schuyler and Anne Spencer were published and in which he also published regularly. His essay The Talented Tenth (English for the talented tenth ) described his concept of the formation of an elite of black Americans. With these activities he became the declared political antithesis and opponent of Booker T. Washington. In contradiction to the opportunistically adapted positions of Washington, he appeared as an increasingly radical advocate or forerunner of black nationalism.

In 1911 he became a member of the Socialist Party , from which he resigned a year later. From 1917 to 1918 he promoted the participation of African Americans in World War I and fought against their discrimination in military service. Influenced by the 14-point program that US President Woodrow Wilson announced shortly before the end of the war, Du Bois directed his political activities to the African continent, for whose black residents he advocated the same national self-determination rights that Wilson had granted the Europeans. After the war, he organized the first Pan-African Congress in Paris in 1919 as a meeting of people of African descent, which was followed by other congresses in Brussels , London (1921 and 1923), Lisbon and New York City (1927), among others . Topics were the situation in the diaspora , the process of decolonization and the conclusion of peace in Europe.

In 1919, Du Bois first published The Brownies Book , a monthly children's magazine whose goal was to “enable children of color to see that being colored is normal and beautiful. To acquaint you with black history and achievements. To give them the knowledge that other children of color grew up beautiful, useful and famous. "

In the 1920s he toured West Africa and the Soviet Union and published other writings, including novels (see also: African literature: Négritude ). From 1930 he tried harder to democratize the NAACP; The changes failed in his eyes, to which the world economic crisis also contributed, which pushed the question of the emancipation of Afro-Americans into the political background. In 1934 Du Bois gave up his offices. An extensive journey through Europe , Japan and China followed . In his writings he dealt with racism, colonialism and democracy.

In 1944 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters . In 1945 he organized the fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester . In 1948 he resigned from the NAACP because of its support for Henry Wallace as a presidential candidate for the Progressive Party and disputes over the attitude to the Cold War . In 1949 he took part in several peace conferences in Paris and Moscow and became an important advocate of the peace movement through his opposition to the atomic bomb . Under Joseph McCarthy , Du Bois was prevented from doing his work because of his pacifist commitment and his socialist ideals; he traveled through Europe, China and the Soviet Union.

In 1951 he married the American writer Shirley Graham . In 1958 he took part in a conference in Tashkent at which the Afro-Asiatic writers' organization was founded. In 1959 he received the Lenin Peace Prize in Moscow. In 1961 he became a member of the Communist Party of the USA ; in the same year he and his wife moved to Ghana, where his friend Kwame Nkrumah had become the first prime minister and, after the proclamation of the republic, the first state president. In the last years of his life he worked on the Encyclopedia Africana . On August 27, 1963, the day before the historic Black Movement March on Washington with Martin Luther King's I Have a Dream speech , Du Bois died in Accra . Shortly before, he had taken on Ghanaian citizenship.

His birthplace, which has only survived as a ruin, has been registered as a National Historic Landmark in the National Register of Historic Places since 1976 under the name WEB Dubois Boyhood Homesite .

On August 27, 2019 , a Berlin memorial plaque was unveiled at his former residence, Berlin-Kreuzberg , Oranienstrasse 130 .

Works

- The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America. 1638-1870. Dissertation, 1896 digitized version (1904)

- The Philadelphia Negro. Research paper, 1899.

- The Souls of Black Folk. Collection of articles, 1903 (German: Die Seelen der Schwarzen. Orange-press , Freiburg 2003, ISBN 3-936086-07-9 ).

- The Quest of the Silver Fleece. Novella, 1911.

- On shame about oneself. An essay on racial pride. 1933

- Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880. 1935

- Dusk of Dawn. An essay toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. 1940.

- The black flame. Novel trilogy, 1957–1961.

- The autobiography of WEB Du Bois. A soliloquy on viewing my life from the last decade of its first century. 1968; (German: My way, my world. Memoirs, Dietz, Berlin Ost 1965)

- Against Racism. Unpublished Essays, Papers, Addresses, 1887–1961. Edited by Herbert Aptheker , The University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst 1988, ISBN 0-87023-624-5 .

- WEB Du Bois as editor - online in the Internet Archive

literature

- Kwame Anthony Appiah : Lines of Descent: WEB Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity . Harvard University Press , Cambridge, Massachusetts 2014.

- Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst: WEB Du Bois in Berlin . In: Ulrich van der Heyden, Joachim Zeller (ed.): “… Power and share in world domination” - Berlin and German colonialism. Unrast-Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-89771-024-2

- Hamilton Beck: WEB Du Bois as a Study Abroad Student in Germany, 1892-1894. In: Frontiers. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad . Vol. 2, No. 1, Fall 1996, pp. 45-63. ISSN 1085-4568

- Hamilton Beck: Censoring Your Ally: WEB Du Bois in the German Democratic Republic. In: Crosscurrents. African Americans, Africa, and Germany in the Modern World . Ed. David McBride, Leroy Hopkins, and C. Aisha Blackshire-Belay. Camden House, 1998. pp. 197-232. ISBN 978-1-57113-098-3

- Hamilton Beck: The autobiography of WEB Du Bois in GDR translation. In: Journal of Germanists in Romania. 6th year, issue 1–2 (11–12), 1998, pp. 169–173. ISBN 973-9368-06-9

- Paul Gilroy : The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. Chapter 4, 1993. ISBN 0-674-07606-0

- Amy Helene Kirschke: Art in Crisis. WEB Du Bois and the Struggle for African American Identity and Memory. Bloomington 2007, ISBN 978-0-253-21813-1

- David Levering Lewis : WEB Du Bois. Biography of a Race, 1868-1919. Owl Books, 1994. Winner of the 1994 Pulitzer Prize in the Biographies category . ISBN 978-0-8050-3568-1

- David Levering Lewis: WEB Du Bois. The Fight for Equality and the American Century 1919-1963. Owl Books, 2001. Covers the second half of the life of WEB Du Bois, 2001 Pulitzer Prize winner in the Biographies category . ISBN 978-0-8050-6813-9

- Manning Marable : WEB Du Bois - Black Radical Democrat. Paradigm Publishers, 2005, ISBN 1-59451-018-0

- Hanna Meuter : "I sing America too". American Negro seals. Bilingual. Ed. And transl. Together with Paul Therstappen . Wolfgang Jess, Dresden 1932. With short biographies. 1st row: The new negro. The voice of the awakening Afro-America . Part 1; New edition, ibid. 1959, pp. 13-18

- Aldon Morris: The Scholar Denied: WEB Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. University of California Press, Oakland 2017, ISBN 978-0-520-28676-4

- Carol Polsgrove: Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause , Manchester Univ. Press, Manchester [u. a.] 2012, ISBN 978-0-7190-8901-5

- Shamoon Zamir (Ed.): The Cambridge companion to WEB Du Bois. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [u. a.] 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-69205-2

Web links

- Literature from and about WEB Du Bois in the catalog of the German National Library

- Donald J. Morse: WEB Du Bois (1868-1963). In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- english biography

- Crisis online

- Ursula Trüper: The double consciousness (review of the German edition of Black Folk in the taz of July 24, 2004)

- Infographics

Individual evidence

- ↑ Monika Plessner : I am the darker brother · The literature of black Americans · From the Spirituals to James Baldwin. Fischer Verlag Frankfurt a. M. 1979, ISBN 3-596-26454-5 , p. 119.

- ^ Annotated letter from DuBois of November 7, 1895 to Senator George Frisbie Hoar The commentary reads: “Du Bois's application for aid was rejected by the Slater Fund, but Hayes encouraged him to reapply. The following year, after the exchange of numerous letters, his application was accepted. In the spring of 1892 he received $ 750 from the Slater Fund, $ 375 as a scholarship and $ 375 as a loan. He used those funds, and a second award received the following year, to support his studies at the Friedrich-Wilhelm III Universitat. "

- ↑ Andreas Eckert: Black, beautiful and proud , in the issue of Zeit from September 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Monika Plessner: I am the darker brother · The literature of black Americans · From the Spirituals to James Baldwin. Fischer Verlag Frankfurt a. M. 1979, ISBN 3-596-26454-5 , p. 120.

- ↑ WEB Du Bois: The Souls of Black Folk. Essays and Sketches. McClurg, Chicago 1903, Chapter 14: The Sorrow Songs , p. 252. English original: "it [the Negro folk-song] still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people." Du Bois used black folk and Negro people largely synonymously. To identify the “Negro folk-song” with the spirituals, see Hazel V. Carby: Race Men . Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London, p. 87.

- ^ WE Burghardt Du Bois: The Negro question in the United States . In: Archive for Social Science and Social Policy , Volume 22, 1906, pp. 31–79, archive.org . It is not true that Weber visited Du Bois in Atlanta; they met only briefly in 1904 at a scientific congress that was part of the program of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition , the world exhibition in St. Louis ; see. Lawrence Scaff: Weber's Amerikabild and the African American Experience . In: David McBride, Leroy Hopkins, Carol Blackshire-Belay (Eds.): Crosscurrents: African Americans, Africa, and Germany in the Modern World. Camden House, Columbia 1998, pp. 82–94, here: pp. 86 ff. And 93.

- ↑ Monika Plessner: I am the darker brother · The literature of black Americans · From the Spirituals to James Baldwin. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1979, ISBN 3-596-26454-5 , pp. 1119 ff.

- ↑ Members: WE Burghardt Du Bois. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed February 27, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | You Bois, WEB |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American civil rights activist, sociologist, philosopher, journalist, pacifist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 23, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Great Barrington , Berkshire County , Massachusetts |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 27, 1963 |

| Place of death | Accra , Ghana |