Vigesimal system

The vigesimal system or system of twenty (Latin: vicesimus, the twentieth) is a number system that uses the number twenty as the base .

One possible explanation for the existence of this system is that in addition to the fingers , the toes were also used for counting and arithmetic . Another explanation is turning your hands.

distribution

The vigesimal system was consistently applied in the cultures of Mesoamerica , which is why the numerals in the languages of the language federation there were based on it and had simple names for the powers of twenty. With the implementation of the system of ten in the Spanish colonial era, this counting method has largely been lost even among speakers of indigenous languages in Mexico , but in some places they still count up to 20 or even 99 with traditional numerals.

In Europe there are also traces of a vigesimal system in many languages, but nowhere is the number counted in twenty units beyond the number 99.

The vigesimal system can also be found in other languages of the Eurasian area . This includes:

- Ainu , an isolated language spoken in northern Japan

- Burushaski , an isolated language spoken in northern Pakistan

- Georgian , a South Caucasian language . This language group is isolated insofar as no relationship to any other language group has yet been proven, not even to other Caucasian languages .

European languages

The vigesimal system is represented in Europe in Basque , French , Danish and the Celtic languages as well as a few other languages. While it may be inherited in Basque, it came up later in the other languages. The oldest Celtic language levels, which also include Old Irish and Gallic , did not yet have a vigesimal system; these languages only developed in the Middle Ages. In Danish, too, the twenties system first spread in Central Danish ( Gammeldansk ) in the 13th and 14th centuries. It is only documented very early in French, which makes it possible to borrow from there into other languages. According to Karl Menninger , the European vigesimal system is of Norman origin and was established in northwestern Spain , Portugal , France and the British Isles with the spread of the Normans in the Middle Ages . The linguist Brigitte Bauer also sees no substrate influence in the European vigesimal system , but rather a medieval development.

The linguist Theo Vennemann , on the other hand, postulates a vasconic (Basque) origin for the European vigesimal system , which he equates with old European in the sense of pre- Indo-European . It was used as a substrate in later European languages , for example in many Celtic languages , French and Danish , but this is mostly rejected due to the recent development in these languages.

Possible remnants of a vigesimal system can also be found in Etruscan , where the words for 17, 18 and 19 translated literally mean “20 less 3”, “20 less 2” or “20 less 1”, and in Latin , the 18 ( duodeviginti ) and 19 ( undeviginti ) named in this way.

In the old British monetary system, twenty shillings was one pound sterling.

In his speech I have a dream , Martin Luther King uses the phrase Five score years ago for "a hundred years ago" as an allusion to a similar phrase (originally taken from the Bible) in Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address ( four score and seven years ago ) .

Basque language

The Basque has up to the number 99 is a vigesimal. So 20 is called hogei , 30 hogeita hamar ("twenty and ten"), 31 hogeita hamaika ("twenty and eleven"), 32 hogeita hamabi ("twenty and ten-two"). It is counted in units of twenty : 40 berrogei ("double twenty"), 60 hirurogei ("three-twenty") and 80 laurogei ("four-twenty"). The full tens in between are expressed - similar to the Mesoamerican languages - by adding “ten”: 50 berrogeita hamar (“double twenty and ten”), 70 hirurogeita hamar (“three twenty and ten”), 75 hirurogeita hamabost ("three-twenty and five-ten"), 90 laurogeita hamar ("four-twenty and ten"). From one hundred the Basque numbers follow a decimal system : 100 ehun , 200 berrehun , 300 hirurehun ; with the higher powers of ten mila ( thousand , cf. Spanish mil ) and milioi ( million , Spanish millón ) the word shape indicates a borrowing from Spanish or Vulgar Latin .

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages also have a vigesimal system up to the number 99; the numbers are formed according to the same principle as in Basque.

Irish language

In the Irish traditionally seen in vigesimal with twenty ( fiche ) as a base. Forty is daichead (→ dhá fhichead 2 × 20), sixty is trí fichid (3 × 20), eighty is ceithre fichid (4 × 20). Thirty is fiche a dike (20 + 10), fifty is daichead a dike , 99 is ceithre fichid a naoi déag (4 × 20 + 19).

In the official standard, however, the decimal system is favored.

Scottish Gaelic

In Scottish Gaelic , the base fichead (20) is traditionally counted: 30 deich ar fhichead (10 + 20), 40 dà fhichead (2 × 20), 50 dà fhichead 'sa deich (2 × 20 + 10), 60 trì fichead (3 × 20) and so on up to 180 naoidh fichead (9 × 20).

Welsh language

The Welsh language also traditionally uses twenty ( ugain ) as a base. Deugain are twice twenty ( i.e. 40), trigain three times twenty (= 60) and pedwar ugain four times twenty (= 80). The multiples of ten in between are formed on the basis of the smaller multiple of twenty: Deg ar hugain is thirty ("ten on twenty"), deg a thrigain seventy ("ten on three times twenty") and deg a phedwar ugain ninety ( "Ten by four times twenty"). Fifty, on the other hand, is hanner cant (“half a hundred”). Until the introduction of the decimal system in the monetary system in 1971, papur chwigain (six twenties notes ) was the slang term for the ten shilling note (= 120 pence). In the second half of the 20th century, the decimal system was generally preferred over the traditional vigesimal system.

Breton language

Since Breton is closely related to Welsh, the Vigesimal system is used in this. As in Welsh, 40 is called daou-ugent , 60 tri-ugent and 80 pevar-ugent . 30 has its own designation tregont , while 50 means hanter-kant (“half a hundred”). 70 and 90, on the other hand, are formed on the basis of the smaller multiple of 20 as in the other Celtic languages, so similar to French : dek ha tri-ugent ("ten and three times twenty") and dek ha pevar-ugent (" ten and four times twenty ”).

Danish language

The Danish number system is based - similar to the Basque , Celtic and French number systems - on a vigesimal system, which, however, is only partially used.

While the Scandinavian neighbors (the Norwegians and Swedes ) and the Germans uniformly use the decimal number system, which is almost the only one in today's Europe , the Danes switch from the conventional decimal to a vigesimal counting method when counting from the number 50 (up to and including 99) . For the numerical notation, the Danish number system only uses the decimal Arabic numerals . Since about the middle of the 20th century, an abbreviated typographical spelling and pronunciation of these numerical values became established. It can be seen from it that today's final - the numbers from 50 to 99 - is a remnant of the original posterior link - are styve .

The old Danish word sinde ( -sinds- represents the genitive form) means 'multiplied by', and the word tyve still denotes the number 20. This results in the Danish numerical values from 50 to 99, which are unfamiliar for users of the decimal system Examples are explained:

- halvtreds [indstyve] * = halv-tredje sinde tyve (literally: half-third ** times twenty) = 2½ × 20 = 50

- tres [indstyve] * = tre sinde tyve = 3 × 20 = 60

- halvfjerds [indstyve] * = halv-fjerde sinde tyve (literally: half-fourth ** times twenty) = 3½ × 20 = 70

- firs [indstyve] * = fire sinde tyve = 4 × 20 = 80

- halvfems [indstyve] * = halv-femte sinde tyve (literally: half-fifth ** times twenty) = 4½ × 20 = 90

- nioghalvfems [indstyve] * = ni og halv-femte sinde tyve (literally: nine and half-fifth ** times twenty) = 9 + 4½ × 20 = 99

- However, 100 does not mean “fems”, but et hundrede

- (*) The word parts in [] complement the short form of the numerical word used in everyday life to form a long form.

- (**) The numerical values half-third , half-fourth or half-fifth of this system do not mean about half of three, four or five (i.e. one and a half, two or two and a half), but two and a half (the third half), three and a half (the fourth half) or four and a half (the fifth half). This counting method is also used (as in German) when specifying times, where "half past four (o'clock)" also does not mean "two o'clock" (two as half of four), but rather the time "half an hour past three " , Or " half an hour to four " (halfway between three and four, so basically " 3.5 o'clock " ). The German word one and a half (for one and a half ) is also formed like this, the other (= second) half [ the first whole, the second half ] = 1.5. The Roman denomination of coins Sesterz ( sestertius ) was named according to this principle, namely se [mi] s tertius (as) , which means “the third (As) half” , the sesterce originally had the value of 2½ As.

The same system can be found in the Faroese language .

Some Danish terms, some of which are out of date, which originate from the time of trading in natural produce, allow conclusions to be drawn about a vigesimal system that was originally widespread in everyday life. So even today the Danes (as well as the French and peoples of Celtic descendants ) use - in addition to et dusin (a dozen ) - terms such as et snes (a staircase ; = 20), et skok (a shock , for example when counting of eggs 3 × 20 = 60), as well as et ol (a Wall / Wahl / Oll ; 4 × 20 = 80).

French language

A partial vigesimal system can be found, for example, in standard French : the decimal system is used up to 60 ( soixante ). Then counting continues in blocks of twenty:

- 70: soixante-dix (sixty plus ten)

- 80: quatre-vingts (four times twenty)

- 90: quatre-vingt-dix (four times twenty plus ten)

In Old French, the vigesimal system for even larger numbers was so when in Paris located Hospital Hôpital des Quinze-Vingts , which takes its name from the original 15 x 20 = 300 seats. In the Middle Ages one counted vingt et dix (30), deux vingt (40), deux vingt et dix (50), trois vingt (60).

However, the vigesimal counting does not apply to the French spoken in Belgium and Switzerland , as well as to regional variants in France : There the variants septante (70), octante / huitante (80) and nonante (90) are used, which in standard French France are considered obsolete or apply regionally, although quatre-vingts (80) are used in Belgium .

Resian

The Resian dialect of the Slovenian language , which is spoken in northeastern Italy , uses the vigesimal system in contrast to the neighboring Slovenian and Friulian dialects from 60: 60 is trïkart dwisti (3 × 20), 70 is trïkart dwisti nu dësat (3 × 20 + 10), 80 is štirikrat dwisti (4 × 20) and 90 is štirikrat dwisti nu dësat (4 × 20 + 10).

Albanian

In Albania there are remains of a Vigesimalsystems. So there the number for twenty is njëzet ( një "one" + zet "twenty"); dyzet is forty ( dy "two"). Trizet "sixty" and katërzet "eighty" still exist in dialects . The other numbers for the tens are formed according to the decimal system, so for tridhjetë "thirty" ( tre "three" + dhjetë "ten").

Georgian

In Georgian , between twenty and ninety-nine are counted mixed decimal-vigesimal: 20 ozi, 21 ozdaerti (20 + 1), 25 ozdachuti (20 + 5), 30 ozdaati (20 + 10), 31 ozdatertmeti (20 + 11), 35 ozdatchutmeti (20 + 15), 38 ozdatvrameti (20 + 18), 40 ormozi (2 × 20), 45 ormozdachuti (2 × 20 + 5), 47 ormozdaschvidi (2 × 20 + 7), 50 ormozdaati (2 × 20 + 10 ), 55 ormozdatchutmeti (2 × 20 + 15), 60 samozi (3 × 20), 65 samozdachuti (3 × 20 + 5), 67 samozdaschvidi (3 × 20 + 7), 70 samozdaati (3 × 20 + 10), 75 samozdatchutmeti (3 × 20 + 15), 80 otchmozi (4 × 20) [as in French "quatre-vingts"], 85 otchmozdachuti (4 × 20 + 5), 90 otchmozdaati (4 × 20 + 10), 95 otchmozdachutmeti (4 × 20 + 15), 99 otchmozdazchrameti (4 × 20 + 19) [as in French "quatre-vingt-dix-neuf"]. In the Khewsurian dialect, the counting method also applies to numbers over 100, for example 120 (6 × 20), 140 (7 × 20).

Africa

Yoruba

In Yoruba , 20 is Ogún, 40 Ogójì (= Ogún-mejì [20x2 (ejì)]), 60 Ogota (= Ogún-metà [20x3 (eta)]), 80 Ogorin (= Ogùn-mèrin [20x4 (erin)]) , 100 Ogurun (= Ogùn-márùn [20x5 (àrún)]), 16 Eérìndílógún (4 less than 20), 17 Etadinlogun (3 less than 20), 18 Eejidinlogun (2 less than 20), 19 Okadinlogun (1 less than 20 ), 24 Erinlelogun (4 more than 20) and 25 Aarunlelogun (5 more than 20).

Asia

Dzongkha

In Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan , there is a complete vigesimal system with bases of 20, 400, 8000 and 160,000.

India

In Santali , a Munda language, 50 is bar isi gäl (2 × 20 + 10), in Didei , another Munda language, one counts up to 19 decimal, up to 399 decimal-vigesimal.

Japan

In Ainu , 20 is called hotnep, 30 waupe etu hotnep (10 more up to 2 × 20), 40 tu hotnep (2 × 20) and 100 ashikne hotnep.

Afghanistan and Pakistan

In Gandhara ( Peshawar ) the kharosthi numbers have symbols for 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 20 and 100.

Caribbean

Garifuna

The Garifuna , an indigenous American language in Central America , has borrowed almost all numerals from French; it carries out the vigesimal system up to the number 99 as follows: 20 wine (vingt), 40 biama wine (deux-vingt = 2 × 20), 60 ürüma wine (trois-vingt = 3 × 20), 70 ürüma wine dîsi (trois- vingt-dix = 3 × 20 + 10), 80 gádürü wine (quatre-vingt = 4 × 20), 90 gádürü wine dîsi (quatre-vingt-dix = 4 × 20 + 10), but 30 is called darandi (trente) and 50 dimí san (one half by one hundred). From 100 the decimal system is used.

Mesoamerican languages

In Mesoamerica , twenty was widely used as the basis of the number system and the formation and writing of calendar dates. The numerals of the Mesoamerican languages, which, as languages that were not genetically related to one another, formed a linguistic federation , like the Maya digits, were consistently based on the twenty -digit system . In addition to the Maya languages, these languages also included the Nahuatl of the Aztecs . Simple words for large numbers did not exist for hundred and thousand, but for the powers of twenty, twenty, four hundred, eight thousand, and so on.

It is interesting here that the numerals of Mayathan and the unrelated Nahuatl are put together completely differently, but both consistently build on the powers of twenty.

Nahuatl: Twenty units with four five units

The structure of the Nahuatl numerals shows that a twenty-figure count consists of four units of five. Thus makuili "five" on the root ma ( maitl returned "hand"), while the numbers Six to Nine from chiko ( "opposite [e hand]") and composed the words of one to four (chikuasen, chikome, chikueyi, chiknaui) . For the multiples of five - ten (majtlaktli) and fifteen (kaxtoli) - there are again separate words, whereby majtlaktli (ten) is also associated with maitl "hand". The numerical sequences 11–14 (majtlaktli onse, majtlaktli omome, majtlaktli omeyi, majtlaktli onnaui) and 16–19 (kaxtoli onse, kaxtoli omome, kaxtoli omeyi, kaxtoli onnaui) are composed directly from these numerals and the words for one to four. As with the appearance of the Maya numerals - one line forms a group of five, four lines form a unit of twenty - the way in which the Nahuatl numbers are counted on four hands and feet with a total of twenty fingers and toes is clear.

Maya languages: twenty units with two ten units

In contrast to Nahuatl, the numerals in Mayathan and other Maya languages do not have five as a sub-unit of twenty, but ten (compare thirteen to fifteen: óox lahun, kan lahun, ho 'lahun , made up of lahun "ten" and óox, kan , ho , "three, four, five"). The twenties system with the subunit ten can also be found in the Maya languages of Guatemala (for example in the Quiché language and the Cakchiquel language ), but the numerals are formed differently in detail, for example with regard to the order of the ones, twenties and four hundred . The numbers 13–19 are largely similar to those in Mayathan (one + “ten”, compare thirteen to fifteen in Quiché: oxlajuj, kajlajuj, olajuj from oxib, kajib, job and lajuj ), however, in Quiché and Cakchiquel, eleven and twelve follow completely regularly this system (Quiché julajuj, kablajuj versus Mayathan buluk, lahka'a ). In Quiché and Cakchiquel there are two numerals for “twenty”, on the one hand k'alh (corresponding to k'áal in Mayathan), on the other hand winaq , which also means “human”, i.e. all fingers and toes of a person. There are also two numerals for “twenty” in other Maya languages, such as tob and vinik in the Tzotzil .

In addition, these two Maya languages have a special word for eighty, jumuch or jumútch ( ju- as the prefix “one”). From the Popol Vuh written in Quiché, omuch , "five eighties", for "four hundred" is documented as a special formation deviating from the twenty system . In earlier Cakchiquel grammars we still find counting methods in which the basic component of the numeral is the next larger multiple of twenty and is at the end, while in newer grammars the basic component of the numeral is the next lower multiple of twenty and is at the beginning. In addition, k'alh was used more often in the past and winaq was mostly used in later language levels .

The numbers thirty-seven and fifty-seven are mentioned as examples of the different composition of numerals with the same base of a twenty-one system: 37 in Mayathan Uk is lahun katak hun k'áal ("seven [and] ten and one [times] twenty"), in the Cakchiquel and the same Quiché Juwinaq wuqlajuj ("One [times] twenty seven [and] ten"), in the Nahuatl, on the other hand, Sempouali onkaxtoli omome ("One [times] twenty and fifteen and two"). 57 is called again in Mayathan Uk lahun katak ka 'k'áal (“seven [and] ten and two [times] twenty”), in the ancient Cakchiquel language Wuqlajuj roxk'alh (“seven [and] ten [ for counting] before-three [times] -wenty ", from oxk'alh " sixty "), in modern cakchiquel and the same name Quiché Kawinaq wuqlajuj (" two [times] twenty [= human] seven [and] ten " ), in the Nahuatl, on the other hand, Ompouali onkaxtoli omome ("Two [times] - twenty and fifteen and two").

Numerals for powers of twenty

| Powers of twenty in Mesoamerican languages | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical value | German | Mayathan | Classic Maya | Nawatl (modern spelling) | Classic Nahuatl | Nahuatl word root | Aztec pictogram | ||

| 1 | one | Hun | Jún | Se | Ce | Ce |

|

||

| 20th | Twenty | K'áal | K'alh | Sempouali | Cempohualli (Cempoalli) | Pohualli |

|

||

| 400 | Four hundred | Bak | Baq | Sentzontli | Centzontli | Tzontli |

|

||

| 8000 | Eight thousend | Spades | Piq | Senxikipili | Cenxiquipilli | Xiquipilli |

|

||

| 160,000 | One hundred and sixty thousand | Calab | Qabalh | Sempoualxikipili | Cempohualxiquipilli | Pohualxiquipilli | |||

| 3,200,000 | Three million two hundred thousand | K'inchil | K'intchilh | Sentzonxikipili | Centzonxiquipilli | Tzonxiquipilli | |||

| 64,000,000 | Sixty-four million | Ala | Alauh | Sempoualtzonxikipili | Cempohualtzonxiquipilli | Pohualtzonxiquipilli | |||

Counting in five and twenty units

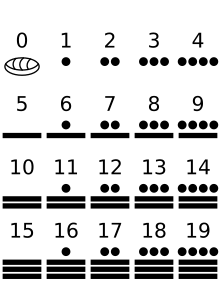

This table shows the Mayan numerals as well as the numerals in Mayathan, Nawatl in modern spelling and classical Nahuatl.

| One to ten (1 - 10) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 one) | 2 (two) | 3 three) | 4 (four) | 5 (five) | 6 (six) | 7 (seven) | 8 (eight) | 9 (nine) | 10 (ten) |

|

|

|||||||||

| Hun | Ka'ah | Óox | Can | Ho ' | Wak | Uk | Waxak | Bolon | Lahun |

| Se | Ome | Yeyi | Naui | Makuili | Chikuasen | Chikome | Chikueyi | Chiknaui | Majtlaktli |

| Ce | Ome | Yei | Nahui | Macuilli | Chicuace | Chicome | Chicuei | Chicnahui | Matlactli |

| Eleven to twenty (11-20) | |||||||||

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14th | 15th | 16 | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th |

|

|

|||||||||

| Buluk | Lahka'a | Óox lahun | Kan lahun | Ho 'lahun | Wak lahun | Uk lahun | Waxak lahun | Bolon lahun | Hun k'áal |

| Majtlactli onse | Majtlaktli omome | Majtlaktli omeyi | Majtlaktli onnaui | Kaxtoli | Kaxtoli onse | Kaxtoli omome | Kaxtoli omeyi | Kaxtoli onnaui | Sempouali |

| Matlactli huan ce | Matlactli huan ome | Matlactli huan yei | Matlactli huan nahui | Caxtolli | Caxtolli huan ce | Caxtolli huan ome | Caxtolli huan yei | Caxtolli huan nahui | Cempohualli |

| Twenty-one to thirty (21-30) | |||||||||

| 21st | 22nd | 23 | 24 | 25th | 26th | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30th |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hump'éel katak hun k'áal | Ka'ah katak hun k'áal | Óox katak hun k'áal | Kan katak hun k'áal | Ho 'katak hun k'áal | Wak katak hun k'áal | Uk katak hun k'áal | Waxak katak hun k'áal | Bolon katak hun k'áal | Lahun katak hun k'áal |

| Sempouali onse | Sempouali omome | Sempouali omeyi | Sempouali onnaui | Sempouali ommakuili | Sempouali onchikuasen | Sempouali onchikome | Sempouali onchikueyi | Sempouali onchiknaui | Sempouali ommajtlaktli |

| Cempohualli huan ce | Cempohualli huan ome | Cempohualli huan yei | Cempohualli huan nahui | Cempohualli huan macuilli | Cempohualli huan chicuace | Cempohualli huan chicome | Cempohualli huan chicuei | Cempohualli huan chicnahui | Cempohualli huan matlactli |

| Thirty-one to forty (31-40) | |||||||||

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Buluk katak hun k'áal | Lahka'a katak hun k'áal | Óox lahun katak hun k'áal | Kan lahun katak hun k'áal | Ho 'lahun katak hun k'áal | Wak lahun katak hun k'áal | Uk lahun katak hun k'áal | Waxak lahun katak hun k'áal | Bolon lahun katak hun k'áal | Ka 'k'áal |

| Sempouali ommajtlaktli onse | Sempouali ommajtlaktli omome | Sempouali ommajtlaktli omeyi | Sempouali ommajtlaktli onnaui | Sempouali onkaxtoli | Sempouali onkaxtoli onse | Sempouali onkaxtoli omome | Sempouali onkaxtoli omeyi | Sempouali onkaxtoli onnaui | Ompouali |

| Cempohualli huan matlactli huan ce | Cempohualli huan matlactli huan ome | Cempohualli huan matlactli huan yei | Cempohualli huan matlactli huan nahui | Cempohualli huan caxtolli | Cempohualli huan caxtolli huan ce | Cempohualli huan caxtolli huan ome | Cempohualli huan caxtolli huan yei | Cempohualli huan caxtolli huan nahui | Ompohualli |

| Twenty to two hundred in steps of twenty (20 - 200) | |||||||||

| 20th | 40 | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 | 140 | 160 | 180 | 200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hun k'áal | Ka 'k'áal | Óox k'áal | Kan k'áal | Ho 'k'áal | Wak k'áal | Uk k'áal | Waxak k'áal | Bolon k'áal | Lahun k'áal |

| Sempouali | Ompouali | Yepouali | Naupouali | Makuilpouali | Chikuasempouali | Chikompouali | Chikuepouali | Chiknaupouali | Majtlakpouali |

| Cempohualli | Ompohualli | Yeipohualli | Nauhpohualli | Macuilpohualli | Chicuacepohualli | Chicomepohualli | Chicueipohualli | Chicnahuipohualli | Matlacpohualli |

| Two hundred twenty to four hundred in steps of twenty (220 - 400) | |||||||||

| 220 | 240 | 260 | 280 | 300 | 320 | 340 | 360 | 380 | 400 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Buluk k'áal | Lahka'a k'áal | Óox lahun k'áal | Kan lahun k'áal | Ho 'lahun k'áal | Wak lahun k'áal | Uk lahun k'áal | Waxak lahun k'áal | Bolon lahun k'áal | Hun bak |

| Majtlaktli onse pouali | Majtlaktli omome pouali | Majtlaktli omeyi pouali | Majtlaktli onnaui pouali | Kaxtolpouali | Kaxtolli onse pouali | Kaxtolli omome pouali | Kaxtolli omeyi pouali | Kaxtolli onnaui pouali | Sentsontli |

| Matlactli huan ce pohualli | Matlactli huan ome pohualli | Matlactli huan yei pohualli | Matlactli huan nahui pohualli | Caxtolpohualli | Caxtolli huan ce pohualli | Caxtolli huan ome pohualli | Caxtolli huan yei pohualli | Caxtolli huan nahui pohualli | Centzontli |

North America

Inuit

The Inuit have digit symbols from 0 to 19, twenty (iñuiññaq) is written with the digit symbols “one” “zero”, 40 with “two” “zero”, 400 with “one” and then two “zeros”.

literature

- Georges Ifrah: Universal History of Numbers . Campus, Frankfurt / Main 1987 2 ; ISBN 3-593-33666-9 .

- Manfred Kudlek: Vigesimal number name systems in languages of Europe and neighboring areas . In: Armin R. Bachmann, Christliebe El Mogharbel, Katja Himstedt (ed.): Form and structure in the language: Festschrift für Elmar Ternes (= Tübingen Contributions to Linguistics . No. 499 ). Narr Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8233-6286-9 , ISSN 0564-7959 , pp. 221-240 .

- John D. Barrow: Why the world is mathematical . Campus, Frankfurt / Main 1993; ISBN 3-593-34956-6 .

- Roberto Dapit, Luigia Negro, Silvana Paletti, Han Steenwijk: PO NÄS, primo libro di lettura in resiano . S. Dorligo della Valle (TS) 1998.

- Nils Th. Grabowski and Katrin Kolmer: Kauderwelsch, Maya for Yucatán word for word . Paperback, ISBN 3-89416-367-4 .

- Nils Th. Grabowski: gibberish, Aztec (Nahuatl) word for word . Paperback, ISBN 3-89416-355-0 .

- Alfredo Herbruger, Eduardo Díaz Barrios: Metodo para aprender a hablar, empty y escribir la lengua Cakchiquel . Guatemala CA 1956, pp. 50-52, 323-326.

- August F. Pott : The linguistic difference in Europe in the numerals demonstrated as well as quinary and vigesimal counting methods. Halle an der Saale 1868; Reprinted Amsterdam 1971.

Web links

- Mexica- Aprende Náhuatl # 72. Los NUMEROS. En nahuatl la numeración es vigesimal, contando por veintenas divididas en unidades de cinco

- Reddit: Nahuatl - números

- David Tuggy T. - Lecciones para un curso del náhuatl moderno

- Michael Dürr: Introduction to the colonial-era Quiché (K'iche ') (PDF, in German) (2.23 MB)

- Introduction into Quiché (English, with old-fashioned Quiché spelling; PDF; 131 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Manfred Kudlek: Vigesimal number name systems in languages of Europe and neighboring areas . In: Armin R. Bachmann, Christliebe El Mogharbel, Katja Himstedt (ed.): Form and structure in the language: Festschrift für Elmar Ternes (= Tübingen Contributions to Linguistics . No. 499 ). Narr Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8233-6286-9 , ISSN 0564-7959 , pp. 221–240 , here p. 238 .

- ↑ Manfred Kudlek: Vigesimal number name systems in languages of Europe and neighboring areas . In: Armin R. Bachmann, Christliebe El Mogharbel, Katja Himstedt (ed.): Form and structure in the language: Festschrift für Elmar Ternes (= Tübingen Contributions to Linguistics . No. 499 ). Narr Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8233-6286-9 , ISSN 0564-7959 , pp. 221–240 , here p. 233 .

- ↑ Brigitte Bauer: Vigesimal numerals in Romance: An Indo-European perspective. In: Bridget Drinka (Ed.): Indo-European Language and Culture in Historical Perspective: Essays in Memory of Edgar C. Polomé. (= General Linguistics . No. 41 ). 2004, ISSN 0016-6553 , p. 21-46 (English).

- ↑ Takasugi Shinji: The Number System of Danish. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019 ; accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Reinhard Goltz: The language of the Finkenwerder fishermen . Studies to develop a technical vocabulary. Ed .: Altonaer Museum in Hamburg. Koehler Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Herford 1984, ISBN 3-7822-0342-9 , p. 232 .

- ^ HA Mascher: The property tax regulation in Prussia based on the laws of May 21, 1861 . Döning, 1862 ( full text ): "The shock is a bill of coins and amounted to 60 old silver groschen or Wilhelminer, 160 pieces of which were minted on the mark under Elector Friedrich II of Saxony and Duke Wilhelm in Meissen around 1408 to 1482."

- ↑ Takasugi Shinji: The Number System of Nahuatl. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017 ; accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Takasugi Shinji: The Number System of Tzotzil. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017 ; accessed on May 5, 2019 .