Ibn al-Nafis: Difference between revisions

m space |

No edit summary |

||

| (923 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Arab polymath and physician (1213–1288)}} |

|||

<!--No-source image [[Image:Pic020.jpg|thumb|right|120px|Ibn al-Nafis]]--> |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} |

|||

<!--Beginning of the [[Template:Infobox Muslim scholars]]--> |

|||

{{Infobox religious biography |

|||

{{Infobox_Muslim scholars | |

|||

| religion = [[Islam]] |

|||

<!-- Scroll down to edit this page --> |

|||

| image = Ibn Al Nafis statue.jpg |

|||

<!-- Philosopher Category --> |

|||

| era = [[Islamic Golden Age]] |

|||

notability = [[List of Islamic studies scholars|Muslim scholar]]| |

|||

| birth_date = 1213 |

|||

| birth_place = [[Damascus]], [[Ayyubid Sultanate]] |

|||

color = #cef2e0 | |

|||

| death_date = 17 December 1288 |

|||

| death_place = [[Cairo]], [[Mamluk Sultanate]] |

|||

| ethnicity = |

|||

| region = [[Syria]] and [[Egypt]] |

|||

| Maddhab = [[Shafi'i school|Shafi'i]]<ref>{{cite journal|title=Ibn Al-Nafis: Discoverer of the Pulmonary Circulation|date=2007 |pmc=6077055 |quote=In addition to his medical studies, Ibn al-Nafis learnt Islamic religious law, and became a renowned expert on Shafi’i school of jurisprudence (Fiqh). He lectured at al-Masruriyya School in Cairo. His name was included in a book on “Great Classes of Shafi’i Scholars (Tabaqat al-Shafi’iyyin al-Kubra) by [[Taj al-Din al-Subki]] indicating his fame in religious law. |last1=Amr |first1=S. S. |last2=Tbakhi |first2=A. |journal=Annals of Saudi Medicine |volume=27 |issue=5 |pages=385–387 |doi=10.5144/0256-4947.2007.385 |pmid=17921693 }}</ref> |

|||

| creed = [[Ash'ari]]<ref>Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y., M. Ahmad, and A. Z. Iskandar. "Factors behind the decline of Islamic science after the sixteenth century." History of science and technology in Islam. Available via: http://www.history-science-technology.com/articles/articles%208.html (2001).</ref> |

|||

| main_interests = {{hlist|[[medicine]]|[[surgery]]|[[physiology]]|[[anatomy]]|[[biology]]|[[Islamic studies]]|[[jurisprudence]]|[[philosophy]]}} |

|||

| works = ''[[Sharh al-'Aqa'id al-Nasafiyya|Al-Durra Sharh 'Aqa'id al-Nasafi (Arabic: الدرة شرح عقائد النسفي)]]'',<ref>{{cite book|author=Group of scholars|editor=Ahmad Farid al-Mazidi|title=شروح وحواشي العقائد النسفية لأهل السنة والجماعة (الأشاعرة والماتريدية)|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lpZLDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT15|date=2013|language=ar|publisher=[[w:de:Dar al-Kotob al-ilmiyah|Dar al-Kotob al-'Ilmiyya]]|location=[[Beirut]], [[Lebanon]]|isbn=9782745147851|page=16}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=[[Kamal al-Din ibn Abi Sharif]]|editor=Muhammad al-'Azazi|title=الفرائد في حل شرح العقائد وهو حاشية ابن أبي شريف على شرح العقائد للتفتازاني|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FfpHDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT5|date=2017|language=ar|publisher=[[w:de:Dar al-Kotob al-ilmiyah|Dar al-Kotob al-'Ilmiyya]]|location=[[Beirut]], [[Lebanon]]|isbn=9782745189509|page=4}}</ref> ''Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon'' |

|||

| influences = [[Al-Ghazali]], [[Hippocrates]], [[Galen]], [[Hunayn Ibn Ishaq]], [[Avicenna]], [[al-Zahrawi]] |

|||

| influenced = [[Abu Hayyan Al Gharnati]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Abī Ḥazm al-Qarashī''' ([[Arabic]]: علاء الدين أبو الحسن عليّ بن أبي حزم القرشي ), known as '''Ibn al-Nafīs''' ([[Arabic]]: ابن النفيس), was an [[Arab]] [[polymath]] whose areas of work included [[medicine]], [[surgery]], [[physiology]], [[anatomy]], [[biology]], [[Islamic studies]], [[jurisprudence]], and [[philosophy]]. He is known for being the first to describe the [[pulmonary circulation]] of the [[blood]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Majeed|first1=Azeem|date=2005|title=How Islam changed medicine|journal=BMJ|volume=331|issue=7531|pages=1486–1487|doi=10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1486|pmid=16373721|pmc=1322233}}</ref> The work of Ibn al-Nafis regarding the right sided (pulmonary) circulation pre-dates the later work (1628) of [[William Harvey]]'s ''[[De motu cordis]]''. Both theories attempt to explain circulation. 2nd century Greek physician [[Galen]]'s theory about the physiology of the [[circulatory]] system remained unchallenged until the works of Ibn al-Nafis, for which he has been described as ''"the father of circulatory physiology"''.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Feucht|first1=Cynthia|last2=Greydanus|first2=Donald E.|last3=Merrick|first3=Joav|last4=Patel|first4=Dilip R.|last5=Omar|first5=Hatim A.|title=Pharmacotherapeutics in Medical Disorders|date=2012|publisher=Walter de Gruyter|isbn=978-3-11-027636-7|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ODwkBgAAQBAJ&q=%22father+of+circulatory+physiology%22&pg=PA2|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Moore|first1=Lisa Jean|last2=Casper|first2=Monica J.|title=The Body: Social and Cultural Dissections|date=2014|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-77172-9|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BRIhBQAAQBAJ&q=%22father+of+circulatory+physiology%22&pg=PA124|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=deVries|first1=Catherine R.|last2=Price|first2=Raymond R.|title=Global Surgery and Public Health: A New Paradigm|date=2012|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Publishers|isbn=978-0-7637-8048-7|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8CbVNdBxmdIC&q=%22father+of+the+theory+of+circulation%22&pg=PA39|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- Images --> |

|||

image_name = | |

|||

image_caption = | |

|||

signature = | |

|||

<!-- Information --> |

|||

name = '''Ala-al-din abu Al-Hassan Ali ibn Abi-Hazm al-Qarshi al-Dimashqi''' | |

|||

title= '''Ibn al-Nafis''' | |

|||

birth = [[1213]] | |

|||

death = [[1288]] | |

|||

Ethnicity = [[Arab]] | |

|||

Region = [[Syria]] and [[Egypt]] | |

|||

Maddhab = [[Shafi`i]] | |

|||

school tradition= [[Sunni]] | |

|||

main_interests = [[Islamic medicine|Medicine, Anatomy, Biology, Physiology, Surgery]], [[Islamic astronomy|Astronomy, Cosmology]], [[Futurology]], [[Geography]], [[Geology]], [[Arabic grammar|Grammar, Linguistics]], [[Historiography of early Islam|History]], [[Arabic literature|Literature]], [[Logic in Islamic philosophy|Logic]], [[Early Islamic philosophy|Philosophy]], [[Psychology]], [[Islamic science|Science]], [[Science fiction|Science Fiction]], [[Scientific skepticism|Scientific Skepticism]], [[Early Muslim sociology|Sociology]], [[Theosophy (history of philosophy)|Theosophy]], [[Islamic studies|Islamic Studies]], [[Fiqh|Islamic Jurisudence]], [[Sharia|Sharia Law]], [[Kalam|Islamic Theology]] | |

|||

notable idea= Discovered [[circulatory system]], [[pulmonary circulation]], [[coronary circulation]], [[metabolism]], etc. <br> Discredited [[Avicenna|Avicennian]] and [[Galen]]ic theories on [[humorism|four humours]], [[Pulse|pulsation]], [[bone]]s, [[muscle]]s, [[intestine]]s, [[Sensory system|sensory organs]], [[Bile|bilious]] [[Canal (anatomy)|canals]], [[esophagus]], [[stomach]], etc. <br> Wrote earliest fictional work dealing with [[desert island]], [[coming of age]] and [[science fiction]]. | |

|||

works = ''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon, The Comprehensive Book on Medicine, Theologus Autodidactus, The Summary of Law, Kitab al-Mukhtar fi al-Aghdhiya, Road to Eloquence, A Short Account of the Methodology of Hadith'' | |

|||

influences = [[Hippocrates]], [[Aristotle]], [[Galen]], [[Muhammad]], [[Muhammad ibn Idris ash-Shafi`i|al-Shafi`i]], [[Hunayn ibn Ishaq]], [[Avicenna]], [[Ibn Tufail|Abubacer]] | |

|||

influenced = Tāj al-Dīn al-Subkī, Ibn Qadi Shuhba, Andrea Alpago, [[Michael Servetus]], [[Realdo Colombo]], [[William Harvey]] | |

|||

}} |

|||

<!--End of the template--> |

|||

'''Ala-al-din abu Al-Hassan Ali ibn Abi-Hazm al-Qarshi al-Dimashqi''' ([[Arabic]]: علاء الدين أبو الحسن عليّ بن أبي حزم القرشي الدمشقي ) (born [[1213]] - died [[1288]]), also known as '''Ibn al-Nafis''' ([[Arabic]]: ابن النفيس ), was an [[Arab]] [[Muslim]] [[polymath]]: a [[Islamic medicine|physician, anatomist, biologist, physiologist, surgeon]], [[Islamic astronomy|astronomer, cosmologist]], [[futurist]], [[geographer]], [[geologist]], [[Arabic grammar|grammarian, linguist]], [[Historiography of early Islam|historian]], [[Arabic literature|litterateur]], [[Logic in Islamic philosophy|logician]], [[Early Islamic philosophy|philosopher]], [[Psychology|psychologist]], [[Islamic science|scientist]], [[science fiction]] writer, [[Scientific skepticism|skeptic]], [[Early Muslim sociology|sociologist]], [[Theosophy (history of philosophy)|theosophist]], [[Ulema|Islamic scholar]], [[Shafi`i]] [[Fiqh|jurist]] and [[Sharia|lawyer]], and [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]] [[Kalam|theologian]]. |

|||

As an early anatomist, Ibn al-Nafis also performed several human [[dissection]]s during the course of his work,<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Patrice Le Floch-Prigent and Dominique Delaval|title=The discovery of the pulmonary circulation by Ibn al Nafis during the 13th century: an anatomical approach|journal=[[The FASEB Journal]] |date=April 2014|volume=28|url=http://www.fasebj.org/content/28/1_Supplement/543.9.short}}</ref> making several important discoveries in the fields of [[physiology]] and [[anatomy]]. Besides his famous discovery of the [[pulmonary circulation]], he also gave an early insight of the [[coronary circulation|coronary]] and [[Microcirculation|capillary circulations]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Szasz|first1=Theodora|last2=Tostes|first2=Rita C. A.|title=Vascular Smooth Muscle Function in Hypertension|date=2016|publisher=Biota Publishing|isbn=978-1-61504-685-0|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XjZgDQAAQBAJ&q=coronary+Ibn+al-Nafis&pg=PA3|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Mantzavinos|first1=C.|title=Explanatory Pluralism|date=2016|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-12851-4|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vXQZDAAAQBAJ&q=capillary+Ibn+al-Nafis&pg=PA95|language=en}}</ref> He was also appointed as the chief physician at al-Naseri Hospital founded by [[Sultan]] [[Saladin]]. |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis is most famous for being the first physician to describe [[pulmonary circulation]]<ref>S. A. Al-Dabbagh (1978). "Ibn Al-Nafis and the pulmonary circulation", ''[[The Lancet]]'' '''1''', p. 1148.</ref> and [[coronary circulation]],<ref name=Nagamia/> which form the basis of the [[circulatory system]], for which he is considered the father of the theory of circulation.<ref>Chairman's Reflections (2004), "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting", ''Heart Views'' '''5''' (2), p. 74-85 [80].</ref> He was also an early proponent of [[Biomedical research|experimental medicine]], postmortem [[autopsy]], and human [[dissection]],<ref>Ingrid Hehmeyer and Aliya Khan (2007), "Islam's forgotten contributions to medical science", ''Canadian Medical Association Journal'' '''176''' (10), p. 1467-1468 [1467].</ref><ref>[http://encyclopedia.farlex.com/Islamic+medicine Islamic medicine], ''[[Hutchinson Encyclopedia]]''.</ref> first described the concept of [[metabolism]],<ref name=Roubi/> and developed new systems of [[physiology]] and [[psychology]] to replace the [[Avicenna|Avicennian]] and [[Galen]]ic systems, while discrediting many of their erroneous theories on the [[humorism|four humours]], [[Pulse|pulsation]],<ref>Fancy, p. 3 & 6</ref> [[bone]]s, [[muscle]]s, [[intestine]]s, [[Sensory system|sensory organs]], [[Bile|bilious]] [[Canal (anatomy)|canals]], [[esophagus]], [[stomach]], and the [[anatomy]] of almost every other part of the [[human body]].<ref name=Oataya/> Ibn al-Nafis also drew [[diagram]]s to illustrate different body parts in his new physiological system.<ref>Dr Ibrahim Shaikh (2001), [http://muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=209 Who Discovered Pulmonary Circulation, Ibn Al-Nafis or Harvey?], FSTC.</ref> |

|||

Apart from medicine, Ibn al-Nafis studied [[jurisprudence]], [[literature]] and [[theology]]. He was an expert on the [[Shafi'i]] school of jurisprudence and an expert [[physician]].<ref name="Haddad" /> The number of medical textbooks written by Ibn al-Nafis is estimated at more than 110 volumes.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Numan|first1=Mohammed T.|title=Ibn Al Nafis: His Seminal Contributions to Cardiology|journal=Pediatric Cardiology|date=6 August 2014|volume=35|issue=7|pages=1088–90|doi=10.1007/s00246-014-0990-7|pmid=25096906|s2cid=683719}}</ref> |

|||

Besides his medical contributions, his works on fictional [[Arabic literature]] included ''Theologus Autodidactus'', which is considered the earliest example of a [[desert island]] story, a [[coming of age]] story, and a [[science fiction]] story, through which he expressed many of his religious and philosophical views on a wide variety of scientific subjects.<ref name=Roubi/> |

|||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

==Biography== |

== Biography == |

||

Ibn al-Nafis was born in 1213 to an [[Arab]] family<ref name="مكتب المطبوعات الإسلامية - الطبعة العاشرة, حلب">{{cite book |last1= أبو غدة|first1=عبد الفتاح |title=قيمة الزمن عند العلماء |publisher= مكتب المطبوعات الإسلامية – الطبعة العاشرة, حلب|page=73 |date=1984 }}</ref> probably at a village near [[Damascus]] named Karashia, after which his [[Nisba (onomastics)|Nisba]] might be derived. Early in his life, he studied theology, philosophy and literature. Then, at the age of 16, he started studying medicine for more than ten years at the [[Nur al-Din Bimaristan|Nuri Hospital]] in Damascus, which was founded by the [[Turkoman (ethnonym)|Turkoman]] emir of [[Aleppo]] and Damascus, [[Nur ad-Din, atabeg of Aleppo|Nur-al Din Muhmud ibn Zanki]],<ref>{{cite book |title=The Crusades |first=Nikolas |last=Jaspert |publisher=Taylor & Francis |page=73 |year=2006 }}</ref> in the 12th century. He was contemporary with the famous Damascene physician [[Ibn Abi Usaibia]] and they both were taught by the founder of a medical school in Damascus, [[Al-Dakhwar]]. [[Ibn Abi Usaibia]] does not mention Ibn al-Nafis at all in his [[biographical dictionary]] "Lives of the Physicians". The seemingly intentional omission could be due to personal animosity or maybe rivalry between the two physicians.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Prioreschi|first1=Plinio|title=A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine|date=1996|publisher=Horatius Press|isbn=978-1-888456-04-2|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q0IIpnov0BsC&q=%22Abi+Usaibia%22+%22al-nafis%22&pg=PA270|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

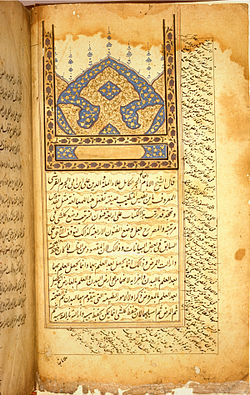

[[Image:ibn_al-nafis_page.jpg|300px|thumb|The opening page of one of Ibn al-Nafis's medical works. This is probably a copy made in [[India]] during the 17th or 18th century. ]] |

|||

In 1236, Ibn al-Nafis, along with some of his colleagues, moved to [[Egypt]] under the request of the [[Ayyubid]] sultan [[al-Kamil]]. Ibn al-Nafis was appointed as the chief physician at al-Naseri hospital which was founded by [[Saladin]], where he taught and practiced medicine for several years. One of his most notable students was the famous Christian physician [[Ibn al-Quff]]. Ibn al-Nafis also taught [[jurisprudence]] at al-Masruriyya Madrassa ([[Arabic]]: المدرسة المسرورية). His name is found among those of other scholars, which gives insight into how well he was regarded in the study and practice of religious law. |

|||

He was born in [[1213]] in [[Damascus]]. He attended the Medical College Hospital ([[Bimaristan]] al-Noori) in Damascus. Besidea medicine, Ibn al-Nafis was also learned in [[Arabic literature]], [[Fiqh]] (jurisprudence), [[Kalam]] (theology) and [[early Islamic philosophy]]. He became an expert on the [[Shafi`i]] school of jurisprudence and an expert [[physician]]. |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis lived most of his life in [[Egypt]], and witnessed several pivotal events like the [[Siege of Baghdad (1258)|fall of Baghdad]] and the rise of [[Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo)|Mamluks]]. He even became the personal physician of the sultan [[Baibars]] and other prominent political leaders, thus showcasing himself as an authority among practitioners of medicine. Later in his life, when he was 74 years old, Ibn al-Nafis was appointed as the chief physician of the newly founded al-Mansori hospital where he worked for the rest of his life. |

|||

In [[1236]], Al-Nafis moved to [[Egypt]]. He worked at the Al-Nassri Hospital, and subsequently at the Al-Mansouri Hospital, where he became chief of physicians and the [[Sultan]]’s personal physician. |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis died in Cairo after some days of sickness. His student Safi Abu al-Fat'h composed a poem about him. Prior to his death, he donated his house and library to [[Qalawun complex|Qalawun Hospital]] or, as it was also known, the House of Recovery.<ref name="Dictionary of Scientific Biography">{{cite book|last1=Iskandar|first1=Albert Z.|title=Dictionary of Scientific Biography|pages=602–06}}</ref> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis grew up in a time of political turmoil in Syria and Egypt, during the [[Crusades]] and [[Mongol invasions]]. After the [[Battle of Baghdad (1258)|sack of Baghdad]] in 1258, Syria was soon temporarily occupied by the [[Mongol Empire]] in 1259, who were then subsequently repelled by the Egyptian [[Bahri dynasty]] at the [[Battle of Ain Jalut]] in 1260. Like other traditionalist Muslims in his time, Ibn al-Nafis believed that these invasions may have been a divine punishment from God against Muslims deviating from the [[Sunnah]].<ref name=Fancy-49-59>Fancy, p. 49 & 59</ref> |

|||

== Writings == |

|||

When he died in [[1288]], he donated his house, library and clinic to the Mansuriya Hospital. |

|||

[[File:Ibn al-nafis page.jpg|250px|thumb|The opening page of one of Ibn al-Nafis' medical works. This is probably a copy made in [[India]] during the 17th or 18th century.]] |

|||

=== The Comprehensive Book on Medicine === |

|||

===Religious background=== |

|||

The most voluminous of his books is ''[[Al-Shamil fi al-Tibb]]'' (The Comprehensive Book on Medicine), which was planned to be an encyclopedia comprising 300 volumes. However, Ibn al-Nafis managed to publish only 80 before his death, and the work was left incomplete. Despite this fact, the work is considered one of the largest medical encyclopedias ever written by one person, and it gave a complete summary of the medical knowledge in the Islamic world at the time. Ibn al-Nafis bequeathed his encyclopedia along with all of his library to the Mansoory hospital where he had worked before his death. |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis was an orthodox [[Sunni Islam|Sunni Muslim]] and an [[Ulema|Islamic scholar]] of the [[Shafi`i]] school of [[Fiqh]] (Islamic jurisprudence) and [[Sharia]] (Islamic law). He wrote a number of works on [[Kalam]] (Islamic theology) and [[early Islamic philosophy]], and was particularly interested in reconciling [[reason]] with [[revelation]] and blurring the line between the two. Unlike some of his contemporaries and predecessors, he made no distinction between philosophy and theology, hence he may arguably be described as a [[Theosophy (history of philosophy)|theosophist]]. Ibn al-Nafis adhered to the teachings of the [[Qur'an]] and accepted the authority of the [[hadith]]s, but required each hadith to be [[Rationality|rationally]] acceptable.<ref>Fancy, p. 41</ref> |

|||

Along the time, much of the encyclopedia volumes got lost or dispersed all over the world with only 2 volumes still being extant in Egypt. The Egyptian scholar [[Youssef Ziedan]] started a project of collecting and examining the extant manuscripts of this work that are cataloged in many libraries around the world, including the [[Cambridge University Library]], the [[Bodleian Library]], and the [[Lane Medical Library]] at [[Stanford University]].<ref name="Dictionary of Scientific Biography" /> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis, who grew up in a time of political turmoil during the [[Crusades]] and [[Mongol invasions]], commented on these conflicts and, like other traditionalist Muslims in his time, believed that these invasions may have been a divine punishment from God against Muslims deviating from the [[Sunnah]]. As a result, the [[Early Islamic philosophy#Falsafa|falsafa]], some of whom held ideas incompatible with the Sunnah, became targets of criticism from a number of traditionalist Muslims. Ibn al-Nafis, who was a traditionalist himself, made an attempt at reconciling [[reason]] with [[revelation]] in some of his works to show that there is harmony between religion and philosophy. Being a traditionalist, Ibn al-Nafis also disliked the misuse of [[wine]] as [[self-medication]], while citing both medical and religious reasons against it, arguing that "I will not meet God, the Most High, with any wine in me." His image as a God-fearing and Sunnah-abiding religious scholar, an intelligent rational philosopher, and an accomplished medical physician, all had a positive impression on later Islamic scholars attempting to reconcile [[faith]] with reason.<ref name=Fancy-49-59/> |

|||

=== Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon === |

|||

===Legacy=== |

|||

Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun ("Commentary on Anatomy in Books I and II of Ibn Sina's Kitab al-Qanun"), published when Ibn al-Nafis was only 29 years old, still it is regarded by many as his most famous work. While it did not prove to be as popular as his medical encyclopedia in the Islamic circles, the book is of great interest today specially for science historians who are mostly concerned with its celebrated discovery of the [[pulmonary circulation]]. |

|||

During and after his lifetime, Ibn al-Nafis' 80-volume medical [[encyclopedia]], ''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine'', had eventually replaced ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'' of [[Avicenna]] (Ibn Sina) as a medical authority in the [[Islamic Golden Age|medieval Islamic world]]. Arabic biographers and [[review]]ers from the 13th century onwards considered Ibn al-Nafis the greatest physician in history, some referring to him as "the second Ibn Sina" and others considering him even greater than all his predecessors. The biographers Tāj al-Dīn al-Subkī (d. 1370) and Ibn Qadi Shuhba wrote:<ref>Fancy, p. 58 & 61</ref> |

|||

The book discusses the anatomical concepts of Avicenna's Canon. It starts with a preface in which Ibn al-Nafis talks about the importance of the anatomical knowledge for the physician, and the vital relationship between [[anatomy]] and [[physiology]]. He then proceeds to discuss the anatomy of the body which he divides into two types; the general anatomy which is the anatomy of the bones, muscles, nerves, veins and arteries; and special anatomy which is concerned with the internal parts of the body like the heart and lungs. |

|||

{{quote|"As for medicine, there has never been anyone on this earth like [Ibn al-Nafīs]. Some say that after Ibn Sīnā there has never been one like [Ibn al-Nafīs], while some say that he was better than Ibn Sīnā in practical treatment."}} |

|||

What distinguish the book most is the confident language which Ibn al-Nafis shows throughout the text and his boldness to challenge the most established medical authorities of the time like [[Galen]] and [[Avicenna]]. Ibn al-Nafis, thus, was one of the few medieval physicians—if not the only one—who contributed noticeably to the science of [[physiology]] and tried to push it beyond the hatch of the Greco-Roman tradition. |

|||

Shortly after his ''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon'' was re-discovered in modern times, [[George Sarton]], the "father of the [[history of science]]", wrote the following on the significance of Ibn al-Nafis' discovery of pulmonary circulation to the [[history of medicine]]:<ref name=Paul/> |

|||

=== Commentary on Hippocrates' "Nature of Man" === |

|||

{{quote|"If the authenticity of Ibn al-Nafis' theory is confirmed his importance will increase enormously for he must be considered one of the main forerunners of [[William Harvey]] and the greatest physiologist of the [[Middle Ages]]."}} |

|||

The particular manuscript of Ibn al-Nafis' commentary on Hippocrates' ''Nature of Man'' is preserved by the [[United States National Library of Medicine|National Library of Medicine]]. It is unique and significant because it is the only recorded copy that contains the commentary from Ibn al-Nafïs on the Hippocratic treatise on the ''Nature of Man''. Al-Nafïs's commentary [[On the Nature of Man|on the ''Nature of Man'']] is found in Sharh Tabi'at al-Insan li-Burqrat. It offers an idea of medical education during this period, in the form of an ''ijaza'' included with the text. This document reveals that Ibn al-Nafïs had a student named of Shams al-Dawlah Abü al-Fadi ibn Abï al-Hasan al-Masïhï, who successfully read and mastered a reading course associated with the treatise, after which al-Masïhï received this license from Ibn al-Nafïs. Based on evidence from commentaries such as this one, modern scholars know that physicians in this era received a license when they completed a particular part of their training.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/hippocratic.html|title=Islamic Medical Manuscripts: Catalogue – Hippocratic Writings|website=www.nlm.nih.gov|access-date=12 April 2018}}</ref> |

|||

== |

=== Commentary on "Endemics" === |

||

In the second half of the thirteenth century, Ibn al-Nafïs composed the first Arabic commentary on Hippocrates' ''Endemics''. The commentary is lengthy and contains two extant manuscripts, made up of 200 and 192 folios.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Endemics in Context: Greek Commentaries on Hippocrates in the Arabic Tradition|last=Pormann|first=Peter|publisher=Walter de Gruyter & Co.|year=2012|isbn=978-3-11-025979-7|location=Berlin|pages=207}}</ref> Ibn al-Nafïs’ commentary on Hippocrates’ ''Endemics'' in ''Sharh Abidhimya li-Burqrat'' is an analysis of Hippocrates three constitutions. Al-Nafïs revisited the cases of illnesses described by Hippocrates in his text, while comparing and contrasting those cases to his own cases and conclusions. In his commentary, al-Nafïs emphasized disease outbreaks. In one example, he compared a particular outbreak of malnutrition in [[Damascus]], Syria, to an outbreak described by Hippocrates. Like Hippocrates, al-Nafïs constructed an outbreak map and both men concluded that Damascus was the origin of the outbreak. This method of locating an outbreak origin was used by [[John Snow]] 600 years later, when he constructed his own outbreak map.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|title=The Forgotten History of Pre-Modern Epidemiology: Contribution of Ibn al-Nafis In the Islamic Golden Era|last=Kayla|first=Ghazi|publisher=Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée Orientale|year=2017|location=Eastern Mediterranean|pages=855–856}}</ref> |

|||

In [[1924]], an [[Egypt]]ian [[physician]], Dr. Muhyo Al-Deen Altawi, discovered a manuscript from [[1242]], titled ''Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun Ibn Sina'' (''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon''), in the Prussian State Library in [[Berlin]] while studying the history of [[Islamic medicine|Arab Medicine]] at the medical faculty of [[University of Freiburg|Albert Ludwig's University]] in [[Germany]]. This script is considered one of the best scientific books in which Ibn al-Nafis covers in detail the topics of [[anatomy]], [[pathology]] and [[physiology]]. This work contained the earliest descriptions of [[pulmonary circulation]] and [[coronary circulation]], which form the basis of the [[circulatory system]]. |

|||

=== |

=== Other works === |

||

Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a number of books and commentaries on different topics including on [[medicine]], [[law]], [[logic]], [[philosophy]], [[theology]], [[grammar]] and [[Natural environment|environment]]. His commentaries include one on [[Hippocrates]]' book, several volumes on [[Avicenna]]'s ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'', and a commentary on [[Hunayn Ibn Ishaq]]. |

|||

The theory that was accepted, prior to Ibn al-Nafis, was placed by [[Galen]] in the 2nd century and improved by [[Avicenna]] in the 11th century. Galen had theorized that the blood reaching the right side of the [[heart]] went through invisible pores in the cardiac [[septum]], to the left side of the heart, where it mixed with air to create spirit, and was then distributed to the body. According to Galen's views, the venous system was quite separate from the arterial system, except when they came in contact through the unseen pores. |

|||

*''al-Mūjaz fī al-Tibb'' (“A Summary of Medicine”); a short outline of medicine which was very popular among Arab physicians and got translated into [[Turkish language|Turkish]] and [[Hebrew]]. |

|||

Based on his anatomical knowledge, Ibn al-Nafis stated that: |

|||

*''Kitāb al-Mukhtār fī al-Aghḏiyah'' (“The Choice of Foodstuffs”); a largely original contribution which was on the effects of diet on health.<ref>L. Gari (2002), "Arabic Treatises on Environmental Pollution up to the End of the Thirteenth Century", ''Environment and History'' '''8''' (4), pp. 475-488.</ref> |

|||

*''Bughyat al-Tālibīn wa Hujjat al-Mutaṭabbibīn'' (“Reference Book for Physicians”); a reference book for physicians containing his general knowledge to aid physicians in the diagnosis of disease, treatment of illness, and execution of surgical procedures.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web|url=http://www.muslimheritage.com/article/contributions-of-ibn-al-nafis|title=Contributions of Ibn al-Nafis to the Progress of Medicine and Urology|last=Abdel-Halim|first=Rabie El-Said|website=Muslim Heritage}}</ref><ref name=":4" /> |

|||

*''al-Muhaḏḏab fī al-Kuhl'' (“Polished Book on [[ophthalmology]]”); an original book on ophthalmology. Ibn al-Nafis made this book to polish and build off of concepts in ophthalmology originally made by [[Masawaiyh]] and [[Ibn Ishaq]].<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=https://explorable.com/islamic-ophthalmology|title=Ilamic ophthalmology|last=Shuttleworth|first=Martyn|date=2009|website=Explorable}}</ref> |

|||

*''Sharḥ Masā’il Hunayn'' (“Commentary on [[Hunayn Ibn Ishaq]]'s Questions”). |

|||

*''al-Risālah al-Kāmiliyyah fī al-Ssīrah al-Nabawiyyah''; (“[[Theologus Autodidactus]]”); a Philosophical treatise that is claimed by some to be the first [[Philosophical novel|theological novel]].<ref name=":3" /> |

|||

== Anatomical discoveries == |

|||

<blockquote>"...the blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa ([[pulmonary artery]]) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa ([[pulmonary vein]]) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit..."</blockquote> |

|||

[[File:Ibn an-Nafis, Commentary on Avicenna's Wellcome L0011502.jpg|thumb|right|A manuscript page from Ibn al-Nafis' Commentary on Avicenna's Canon]] |

|||

In 1924, Egyptian [[physician]], Muhyo Al-Deen Altawi, discovered a manuscript entitled, ''Sharh tashrih al-qanun li’ Ibn Sina'', or "[[Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon]]" in the [[Prussian State Library]] in [[Berlin]] while studying the history of Arabic Medicine at the medical faculty of Albert Ludwig's University. This manuscript covers in detail the topics of [[anatomy]], [[pathology]], and [[physiology]]. This is the earliest description of [[pulmonary circulation]].<ref name="Haddad">{{cite journal|title=A Forgotten Chapter in the History of the Circulation of Blood|last=Haddad|first=Sami|author2=Amin A. Khairallah|year=1936|journal=Annals of Surgery |pages=1–8|pmc=1390327|pmid=17856795|volume=104|issue=1|doi=10.1097/00000658-193607000-00001}}</ref> |

|||

=== Pulmonary circulation === |

|||

Elsewhere in his book, he said: |

|||

The most commonly accepted theory of cardiac function prior to Ibn al-Nafis was that of [[Galen]]. Galen taught that the blood reaching the right side of the [[heart]] went through invisible pores in the cardiac septum, to the left side of the [[heart]], where it mixed with air to create spirit, and was then distributed to the body. According to Galen, the [[venous system]] was separate from the [[arterial system]] except when they came in contact through the unseen pores. |

|||

... |

|||

The newly-discovered manuscript of Ibn al-Nafis was translated by Max Meyerhof. It included critiques of Galen's theory, including a discussion on the pores of the heart. Based on animal [[dissection]], Galen hypothesized [[porosity]] in the [[septum]] in order for blood to travel within the heart as well as additional help on the part of the [[lungs]]. However, he could not observe these pores and so thought they were too small to see. “Ibn al-Nafīs's critiques were the result of two processes: an intensive theoretical study of medicine, physics, and theology in order to fully understand the nature of the living body and its soul; and an attempt to verify physiological claims through observation, including [[dissection]] of animals.”<ref name="IBN AL-NAFĪS AND PULMONARY TRANSIT">{{cite web|last1=Fancy|first1=DNayhan|title=Ibn Al-Nafīs and Pulmonary Transit|url=http://www.qdl.qa/en/ibn-al-naf%C4%ABs-and-pulmonary-transit|website=Qatar National Library|access-date=22 April 2015|date=16 October 2014}}</ref> Ibn al-Nafis rejected Galen's theory in the following passage:<ref name="IBN AL-NAFĪS AND PULMONARY TRANSIT" /><ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal|title=Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from Antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis|journal=Hamdard Medicus|date=1994|volume=37|issue=1|pages=24–26}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>"The heart has only two [[ventricle (heart)|ventricles]] ...and between these two there is absolutely no opening. Also dissection gives this lie to what they said, as the septum between these two cavities is much thicker than elsewhere. The benefit of this blood (that is in the right cavity) is to go up to the lungs, mix with what is in the lungs of air, then pass through the arteria venosa to the left cavity of the two cavities of the heart..."</blockquote> |

|||

<blockquote>The blood, after it has been refined in the right cavity, must be transmitted to the left cavity where the (vital) spirit is generated. But there is no passage between these cavities, for the substance of the heart is solid in this region and has neither a visible passage, as was thought by some persons, nor an invisible one which could have permitted the transmission of blood, as was alleged by Galen.</blockquote> |

|||

In describing the anatomy of the [[lungs]], Ibn al-Nafis stated: |

|||

He posited that the "pores" of the heart are closed, that there is no passage between the two chambers, and the substance of the heart is thick. Instead, Ibn al-Nafis hypothesized that blood rose into the lungs via the arterial vein and then circulated into the left cavity of the heart.<ref name="ReferenceA" /> He also believed that blood (spirit) and air passes from the lung to the left ventricle and not in the opposite direction.<ref name="ReferenceA" /> Some points that conflict with Ibn al-Nafis' are that there are only two [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricles]] instead of three (Aristotle's, 4th century BC) and that the [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricle]] gets its energy from the blood flowing in the vessels running in the [[coronary vessels]], not from blood deposited in the right [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricle]].<ref name="ReferenceA" /> |

|||

<blockquote>"The lungs are composed of parts, one of which is the [[bronchi]]; the second, the branches of the arteria venosa; and the third, the branches of the vena arteriosa, all of them connected by loose porous flesh."</blockquote> |

|||

Based on his anatomical knowledge, Ibn al-Nafis stated: |

|||

He then added: |

|||

<blockquote>Blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber, but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa ([[pulmonary artery]]) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa ([[pulmonary vein]]) to reach the left chamber of the heart, and there form the vital spirit....<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=KTWDxDEY-Q0C&pg=PA99 The Pursuit of Learning in the Islamic World, 610–2003 By Hunt Janin, Pg99]</ref><ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=ysB4DTRgh5sC&pg=PA295 Saints and saviours of Islam, By Hamid Naseem Rafiabadi, p. 295]</ref></blockquote> |

|||

<blockquote>"... the need of the lungs for the vena arteriosa is to transport to it the blood that has been thinned and warmed in the heart, so that what seeps through the pores of the branches of this vessel into the [[alveoli]] of the lungs may mix with what there is of air therein and combine with it, the resultant composite becoming fit to be spirit, when this mixing takes place in the left cavity of the heart. The mixture is carried to the left cavity by the arteria venosa." </blockquote> |

|||

Elsewhere in this work, he said: |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis also postulated that [[nutrient]]s for heart are extracted from the coronary arteries: |

|||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote>The heart has only two ventricles...and between these two there is absolutely no opening. Also dissection gives this lie to what they said, as the septum between these two cavities is much thicker than elsewhere. The benefit of this blood (that is in the right cavity) is to go up to the lungs, mix with what air is in the lungs, then pass through the arteria venosa to the left cavity of the two cavities of the heart; and of that mixture is created the animal spirit.</blockquote> |

||

=== Coronary circulation === |

|||

Dr. Paul Ghalioungui summarizes the fundamental changes Ibn al-Nafis made to the incorrect Galenic-Avicennian theory that led to his discovery of [[pulmonary circulation]] (lesser [[circulatory system]]) as follows:<ref name=Paul>Dr. Paul Ghalioungui (1982), "The West denies Ibn Al Nafis's contribution to the discovery of the circulation", ''Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ([[cf.]] [http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drpaul.html The West denies Ibn Al Nafis's contribution to the discovery of the circulation], ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'')</ref> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis also postulated that nutrients for heart are extracted from the [[coronary arteries]]:<ref>{{cite book|last1=Prioreschi|first1=Plinio|title=A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine|date=1996|publisher=Horatius Press|isbn=978-1-888456-04-2|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q0IIpnov0BsC&q=++al-Nafis+coronary&pg=PA271|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>Again his [Avicenna's] statement that the blood that is in the right side is to nourish the heart is not true at all, for the nourishment to the heart is from the blood that goes through the vessels that permeate the body of the heart.</blockquote> |

|||

#"Denying the existence of any pores through the [[interventricular septum]]." |

|||

#"The flow of [[blood]] from the [[right ventricle]] to the [[lung]]s where its lighter parts filter into the [[pulmonary vein]] to mix with [[Earth's atmosphere|air]]." |

|||

#"The notion that blood, or spirit from the mixture of blood and air, passes from the lung to the [[left ventricle]], and not in the opposite direction." |

|||

#"The assertion that there are only two [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricles]], not three as stated by [[Avicenna]]." |

|||

#"The statement that the ventricle takes its [[Nutrition|nourishment]] from blood flowing in the [[Blood vessel|vessels]] that run in its substance (i.e. the coronary vessels) and not, as Avicenna maintained, from blood deposited in the right ventricle." |

|||

#"A premonition of the [[capillary]] circulation in his assertion that the pulmonary vein receives what comes out of the [[pulmonary artery]], this being the reason for the existence of perceptible passages between the two." |

|||

=== |

=== Capillary circulation === |

||

Ibn al-Nafis had an insight into what would become a larger theory of the capillary circulation. He stated that "there must be small communications or pores (manafidh in Arabic) between the pulmonary artery and vein,"<ref>{{cite book|last1=Peacock|first1=Andrew J.|last2=Naeije|first2=Robert|last3=Rubin|first3=Lewis J.|title=Pulmonary Circulation: Diseases and Their Treatment, Fourth Edition|date=2016|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-1-4987-1994-0|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pgzYCwAAQBAJ&q=capillary+Ibn+al-Nafis&pg=PA3|language=en}}</ref> a prediction that preceded the discovery of the capillary system by more than 400 years. Ibn al-Nafis' theory, however, was confined to blood transit in the lungs and did not extend to the entire body: |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis' next most important discovery is [[coronary circulation]], the second phase of the [[circulatory system]]. He was the first to realize that the [[nutrition]] of the [[heart]] is extracted from the small [[blood vessel]]s passing through its wall. He wrote:<ref name=Nagamia>Husain F. Nagamia (2003), "Ibn al-Nafīs: A Biographical Sketch of the Discoverer of Pulmonary and Coronary Circulation", ''Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine'' '''1''', p. 22–28.</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>For this reason the arterious vein has solid substance with two layers, in order to make more refined that (the blood) which transsudes from it. The venous artery, on the other hand, has thin substance in order to facilitate the reception of the transsuded [blood] from the vein in question. And for the same reason there exists perceptible passages (or pores) between the two [blood vessels].</blockquote> |

|||

{{quote|"Again his [Avicenna's] statement that the blood that is in the right side is to nourish the heart is not true at all, for the nourishment to the heart is from the blood that goes through the vessels that permeate the body of the heart..."}} |

|||

=== |

=== Pulsation === |

||

Ibn al-Nafis also disagreed with Galen's theory that the heart's pulse is created by the arteries’ tunics. He believed that "the pulse was a direct result of the heartbeat, even observing that the arteries contracted and expanded at different times depending upon their distance from the heart. He also correctly observed that the arteries contract when the heart expands and expand when the heart contracts.<ref name="IBN AL-NAFĪS AND PULMONARY TRANSIT" /> |

|||

While the most important discoveries in the ''Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun Ibn Sina'' (''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon'') were the pulmonary and coronary circulations, this work also contains many other discoveries and discredits many erroneous theories advocated in ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'' by [[Avicenna]] (Ibn Sina) and [[Galen]]. Besides the examples given in this article, the ''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon'' contains numerous other discoveries, criticisms and corrections on the anatomy and physiology of almost every part of the human body, including the bones, muscles, intestines, [[Sensory system|sensory organs]], bilious canals, [[esophagus]], [[stomach]], etc.<ref name=Oataya>Dr. Sulaiman Oataya (1982), "Ibn ul Nafis has dissected the human body", ''Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ([[cf.]] [http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/index.html Ibn ul-Nafis has Dissected the Human Body], ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'').</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Lungs === |

||

In describing the anatomy of the [[lungs]], Ibn al-Nafis said: |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis quotes another error made by Galen, who believed that "[[blood]] reaches the [[brain]] itself at the section called [[Prosencephalon|forebrain]] through the [[Dura mater|duramater]] which divides the vault longitudinally into two equal halves at the [[sagittal suture]]." Ibn al-Nafis criticized this theory and corrected it as follows:<ref name=Oataya/> |

|||

<blockquote>The lungs are composed of parts, one of which is the bronchi; the second, the branches of the arteria venosa; and the third, the branches of the vena arteriosa, all of them connected by loose porous flesh.....The need of the lungs for the vena arteriosa is to transport to it the blood that has been thinned and warmed in the heart, so that what seeps through the pores of the branches of this vessel into the alveoli of the lungs may mix with what there is of air therein and combine with it, the resultant composite becoming fit to be spirit when this mixing takes place in the left cavity of the heart. The mixture is carried to the left cavity by the arteria venosa.<ref name="Haddad" /> </blockquote> |

|||

{{quote|"The blood permeates first to the back ventricle ([[Rhombencephalon|hindbrain]]) then to the other two [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricles]]. [[Dissection]] confirms this and disproves what they say. The [[permeation]] of [[Artery|arteries]] into the [[Skull|cranium]] is well known not to be from the front ventricle."}} |

|||

It is also found that "In the lungs, some blood was filtered through the two tunics (coverings) of the vessel that brought blood to the lungs from the heart. Ibn al-Nafīs called this vessel the ‘artery-like vein’, but we now call it the [[pulmonary artery]]."<ref name="IBN AL-NAFĪS AND PULMONARY TRANSIT" /> |

|||

====Canals==== |

|||

Another example concerns an incorrect theory on the anatomy of the [[Bile|bilious]] [[Canal (anatomy)|canals]] that was supported by Galen and Avicenna, and later repeated by [[Leonardo da Vinci]] and even [[Vesalius]] during the [[early modern period]]. Ibn al-Nafis was the only physician in pre-modern times to prove this theory wrong:<ref name=Oataya/> |

|||

=== Brain === |

|||

{{quote|"He [Galen] claims that another canal goes from the [[Gallbladder|gall bladder]] to the [[Intestine|intestinal]] cavaties. This is completely wrong. We have seen the gall bladder several times and failed to see anything going from it either to the [[stomach]] or to the intestines."}} |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis was also one of the few physicians at the time, who supported the view that the [[brain]], rather than the [[heart]], was the organ responsible for thinking and sensation.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Baker|first1=David B.|title=The Oxford Handbook of the History of Psychology: Global Perspectives|date=2012|publisher=Oxford University Press, USA|isbn=978-0-19-536655-6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9uRnGeBAaRMC&q=%22Ibn+al-Nafis%22+Brain+sensation&pg=PA445|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Other medical contributions == |

|||

====Heart==== |

|||

=== Practice of dissection === |

|||

Another correction he made concerned the incorrect Galenic and Avicennian theories of [[bone]]s being present beneath the human [[heart]]. Ibn al-Nafis proved them both wrong through his own observations and wrote the following criticism on their theories:<ref name=Oataya/> |

|||

There is some debate about whether or not Ibn al-Nafis participated in dissection to come to his conclusions about pulmonary circulation. Although he states in his writings that he was prevented from practicing dissection because of his beliefs, other scholars have noted that Ibn al-Nafis must have either practiced dissection or seen a human heart in order to come to his conclusions.<ref name="ReferenceB">{{cite journal|last1=Said|first1=Hakim Mohammed|title=Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis|journal=Hamdard Medicus|date=1994|volume=37|issue=1|page=29}}</ref> According to one view, his knowledge about the human heart could have been derived from surgical operations rather than dissection.<ref name="ReferenceB" /> Other comments found in Ibn al-Nafis' writings such as dismissing earlier observations with a reference to dissection as proof, however, support the view that he practiced dissection in order to come to his conclusions about the human heart and pulmonary circulation.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Said|first1=Hakim Mohammed|title=Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis|journal=Hamdard Medicus|date=1994|volume=37|issue=1|page=31}}</ref> Ibn al-Nafis' comments to the contrary and the alternate explanations, however, keep his possible practice of dissection in question. |

|||

During Ibn al-Nafis’ studies of the human body, there remains controversy whether he performed dissection, as dissection was mentioned in any texts on jurisprudence or Islamic tradition, and there was no concrete prohibition.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Savage-Smith|first1=Emilie|author-link1=Emilie Savage-Smith|title=Attitudes Toward Dissection in Medieval Islam|journal= Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences|date=1955|volume=50|issue=1|page=74|doi=10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67|pmid=7876530|doi-access=free}}</ref> Though many scholars would argue that Ibn al-Nafis would have needed to perform dissection to be able to see pulmonary circulation. Greek physician, Aelius Galenus' book, “On the Usefulness of the Parts”, explicitly tells his readers to rely on dissection for anatomical knowledge and not rely on books.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Savage-Smith|first1=Emilie|title=Attitudes Toward Dissection in Medieval Islam|journal= Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences|date=1955|volume=50|issue=1|page=91|doi=10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67|pmid=7876530|doi-access=free}}</ref> Thus would give an indication that dissection was not some otherworldly idea but had been looked as an opportunity to better one's knowledge of the human body. |

|||

{{quote|"This is not true. There are absolutely no bones beneath the heart as it is positioned right in the middle of the [[Thoracic cavity|chest cavity]] where there are no bones at all. Bones are only found at the [[chest]] periphery not where the heart is positioned."}} |

|||

In the “Commentary of the anatomy of the Canon of Avicenna”, human anatomy experts such as Patrice Le Floch-Prigent and Dominique Delaval, concluded that Ibn al-Nafis used clinical, physiological, and dissection results in discovering and describing the pulmonary heart circulation in humans.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Floch-Prigent|first1=Patrice|title=The Discovery of the Pulmonary Circulation by Ibn al-Nafis during the 13th Century|date=2014|volume=28|issue=1|page=0}}</ref> Through their study on the “Commentary of the anatomy of the Canon of Avicenna”, they both concluded that Nafis did indeed use dissection to acquire his results, even though the practice of dissection was banned in Muslim tradition. |

|||

====Muscles==== |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis made the following correction concerning human [[muscle]]s, where he also briefly refers to his then forthcoming encyclopedia ''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine'':<ref name=Oataya/> |

|||

=== Urology === |

|||

{{quote|"The most important muscles of a human body total 529, details of which you will read in a book we are writing on medicine with full investigations into their shapes, functions, [[tendon]]s, and origins. The forthcoming book will also contain details about proper [[anatomy]] since what is said about it here, is short and brief."}} |

|||

In his book "Al-Mugiza", Ibn al-Nafis distinguishes the difference between kidney stone and bladder stones. He does this by their pathogenesis and clinical picture. He also discussed the difference between kidney and bladder infections, different types of inflammatory and noninflammatory renal swellings, the conservative management of renal stones and commonly used and well known lithontriptic medicaments.<ref name=":5" /> |

|||

=== |

=== Surgery === |

||

In his ''Kitab al-Shamil'', Ibn al-Nafis gives insight into his view of medicine and human relations. His surgical technique had three stages. Step one which he calls "the stage of presentation for clinical diagnosis" was to give the patient information on how it was to be performed and the knowledge it was based on. Second "the operative stage" was to perform the surgery itself. The final step was to have a post-surgery appointment and a routine of checkups which he calls "the postoperative period". There is also a description of a surgeon's responsibility when working with nurses, patients, or other surgeons.<ref name="Dictionary of Scientific Biography" /> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis corrects another theory on the [[nerve]]s stated by Avicenna, who believed that the [[glossopharyngeal nerve]], [[vagus nerve]] and [[accessory nerve]] arise from the nerve [[ganglion]] and that they are attached to the [[Sigmoid colon|sigmoid]] and [[facial nerve]]s through membranous [[fascia]] so that these five nerves look like one nerve emerging as three branches from the back [[foramen lacerum]]. After Ibn al-Nafis dissected that part of the brain, he wrote the following criticism on this theory:<ref name=Oataya/> |

|||

=== Metabolism === |

|||

{{quote|"About what he [Ibn Sina] said concerning the sixth nerve being attached to the [[facial nerve|fifth]] through membranous facia, I have not so far found a good reason for that attachment, and I have not even verified it. This sixth pair [a confluence of the glossopharyngeal, vagus and accessory nerves] both arises and emerges from behind the fifth, so there is no way it could be attached to it."}} |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis is also credited with providing the earliest recorded reference for the concept of [[metabolism]]:<ref>{{cite web|title=Metabolism: The Physiological Power-Generating Process|url=https://pulse.embs.org/may-2016/metabolism-the-physiological-power-generating-process/|website=pulse.embs.org}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>Both the body and its parts are in a continuous state of dissolution and nourishment, so they are inevitably undergoing permanent change.</blockquote> |

|||

== Theology == |

|||

Another example was Galen's incorrect theory on the [[optic nerve]], in which he stated that the optic nerve "which comes from the right side of the brain goes to the right eye, and the nerve which comes from the left side goes to the left eye." Ibn al-Nafis also proved this theory wrong and stated:<ref name=Oataya/> |

|||

{{Main|Theologus Autodidactus}} |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis' philosophical views are mostly known from his philosophical novel, [[Theologus Autodidactus]]. The novel touches upon a variety of philosophical subjects like [[cosmology]], [[empiricism]], [[epistemology]], [[experimentation]], [[futurology]], [[eschatology]], and [[natural philosophy]]. It deals with these themes and others through the story of a [[feral child]] on a desert island, and the development of his mind after contact with the outside world. |

|||

{{quote|"In fact it is not like that, [but] each nerve goes to the opposite side."}} |

|||

The plot of ''Theologus Autodidactus'' was intended to be a response to [[Ibn Tufail]] (Abubacer), who wrote the first Arabic novel ''[[Hayy ibn Yaqdhan]]'' (''Philosophus Autodidactus'') which was itself a response to [[al-Ghazali]]'s ''[[The Incoherence of the Philosophers]]''. Ibn al-Nafis thus wrote the narrative of ''Theologus Autodidactus'' as a rebuttal of Abubacer's arguments in ''Philosophus Autodidactus''. |

|||

==''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine''== |

|||

The most voluminous of his books is ''Al-Shamil fi al-Tibb'' (''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine''), which was planned to be a medical encyclopedia comprising 300 volumes, but he was only able to complete 80 volumes as a result of his death in 1288. The book is one of the largest known medical encyclopedias in history, and even in its incomplete state, was much larger than the more famous ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'' by [[Avicenna]] (Ibn Sina). However, only a small portion of ''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine'' has survived.<ref>Fancy, p. 61</ref> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis described his book ''Theologus Autodidactus'' as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of Prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world." He presents rational arguments for bodily [[resurrection]] and the [[immortality]] of the human soul, using both demonstrative [[reasoning]] and material from the hadith corpus to prove his case. Later Islamic scholars viewed this work as a response to the [[Metaphysics|metaphysical]] claim of Avicenna and Ibn Tufail that bodily resurrection cannot be proven through reason, a view that was earlier criticized by al-Ghazali.<ref>Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", pp. 42, 60, ''Electronic Theses and Dissertations'', [[University of Notre Dame]].[http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150404020329/http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615/|date=4 April 2015}}</ref> |

|||

===Surgery=== |

|||

A surviving manuscript (MS Z 276) containing volumes 33, 42 and 43 of ''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine'' was found in [[Damascus]] and is available at the Lane Medical Library of [[Stanford University]]. One of the three surviving volumes of ''The Comprehensive Book on Medicine'' is dedicated to [[surgery]], and is divided into three ''talim''. The first ''talim'' is twenty chapters in length and deals with the "general and absolute principles of surgery", the second ''talim'' deals with [[Islamic medicine#Surgical instruments|surgical instruments]], and the third examines every type of surgical operation known to him. Only the first five chapters of the first ''talim'' has been translated into [[English language|English]] and their contents are listed as follows:<ref name=Iskandar>Dr. Albert Zaki Iskandar (1982), "Comprehensive Book on the Art of Medicine", ''Symposium on Ibn al Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ([[cf.]] [http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/iskandar.html Comprehensive Book on the Art of Medicine], ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'')</ref> |

|||

Unlike [[Avicenna]] who supported [[Aristotle]]'s idea of the [[soul]] originating from the heart, Ibn al-Nafis on the other hand rejected this idea and instead argued that the soul "is related to the entirety and not to one or a few organs." He further criticized Aristotle's idea that every unique [[soul]] requires the existence of a unique source, in this case the heart. Ibn al-Nafis concluded that "the soul is related primarily neither to the spirit nor to any organ, but rather to the entire matter whose temperament is prepared to receive that soul" and he defined the soul as nothing other than "what a human indicates by saying ‘[[I (pronoun)|I]]’."<ref>Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006), [http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615 "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150404020329/http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615/ |date=4 April 2015 }}, pp. 209–10 (''Electronic Theses and Dissertations'', [[University of Notre Dame]]).</ref> |

|||

# "On the different stages of surgical operations, and the role of the patient in each stage" |

|||

# "On the role of the physician during the time of presentation, the time of operative treatment, and the time of preservation" |

|||

# "On a detailed discussion of the role of the physician during the time of presentation" |

|||

# "On relating the things to which the physician should pay attention during the time of operative treatment" |

|||

# "On the patient's posture during surgical treatment" |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis dealt with Islamic eschatology in some depth in his ''Theologus Autodidactus'', where he rationalized the Islamic view of eschatology using reason and science to explain the events that would occur according to Islamic [[Islamic eschatology|tradition]]. He presented his rational and scientific arguments in the form of Arabic fiction, hence his [[Theologus Autodidactus]] may be considered the earliest science fiction work.<ref name="Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher">Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", ''Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ([[cf.]] [http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drroubi.html Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080206072116/http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drroubi.html |date=6 February 2008 }}, ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'').</ref> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis states that in order for a surgical operation to be successful, full attention needs to be given to three stages of the operation. The first stage is the pre-operation period which he calls the "time of presentation" when the surgeon carries out a [[diagnosis]] on the affected area of the patient's body. The second stage is the acutal operation which he calls the "time of operative treatment" when the surgeon repairs the affected [[Organ (anatomy)|organs]] of the patient. The third stage is the post-operation period which he calls the "time of preservation" when the patient needs to take care of himself and be taken care of by [[nurse]]s until he recovers "by the will of God". For each stage, he gives detailed descriptions on the roles of the surgeon, patient and nurse, and the manipulation and maintainance of the surgical instruments being used.<ref name=Iskandar/> |

|||

== Possible Western influence == |

|||

==Other medical writings== |

|||

There is currently debate over whether Ibn al-Nafis influenced later Western anatomists such as [[Realdo Columbo]] and [[William Harvey]].<ref>Said, Hakim. "Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from Antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis", ''Hamdard medicus,'', p. 35, 1994</ref><ref>Ghalioungui, P. "Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?", ''Clio medica,'', p. 37, 1983</ref> In AD 1344, Kazrouny wrote a verbatim copy of Ibn al-Nafis' commentary on Canon in his ''Sharh al-Kulliyat''.<ref>Said, Hakim. "Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from Antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis", ''Hamdard medicus,'', p32, 1994</ref><ref name="Ghalioungui, P p38">Ghalioungui, P. "Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?", ''Clio medica,'', p. 38, 1983</ref> In AD 1500, [[Andrea Alpago]] returned to Italy after studying in Damascus.<ref name="Ghalioungui, P p38" /><ref name="Said, Hakim p34">Said, Hakim. "Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from Antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis", ''Hamdard medicus,'', p. 34, 1994</ref> In Alpago's 1547 A.D. publication of ''Libellus de removendis nocumentis, quae accident in regimime sanitatis'', there is a Latin translation containing part of Ibn al-Nafis' commentary on pharmacopeia.<ref name="Ghalioungui, P p38" /><ref name="Said, Hakim p34" /> This was published in Venice during [[Padua#Venetian rule|its rule over Padua]].<ref name="Ghalioungui, P p38" /><ref name="Said, Hakim p34" /> Harvey arrived in Padua in AD 1597.<ref name="Ghalioungui, P p38" /><ref name="Said, Hakim p36">Said, Hakim. "Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from Antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis", ''Hamdard medicus,'', p. 36, 1994</ref> |

|||

His book on [[ophthalmology]] is largely an original contribution. Another famous book, embodying his original contributions, was on the effects of [[diet]] on health, entitled ''Kitab al-Mukhtar fi al-Aghdhiya''. |

|||

The debate currently turns on whether these events are causally connected or are historical coincidences.<ref name="Said, Hakim p36" /> |

|||

===Commentaries=== |

|||

The most famous known work of Ibn al-Nafis is his 20-volume commentary on [[Avicenna]]'s ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'', in which Ibn al-Nafis "elucidated the scientific problems, pointed out the logical conclusions, and explained the medical difficulties" in the text according to the biographers Umarī and al-Safadī. The most famous part of his commentary is the ''Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun Ibn Sina'' (''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon''), in which Ibn al-Nafis made his discovery of [[pulmonary circulation]]<ref>Fancy, p. 62</ref> and [[coronary circulation]].<ref name=Nagamia/> |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a commentary on the last part of [[Avicenna]]'s ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'' concerning [[Remedy|remedies]], which was later translated into [[Latin]] by Andrea Alpago (d. 1522) and published in Europe in 1547. It is believed that Ibn al-Nafis' ''Commentary on Anatomy in Ibn Sina's Canon'', which first described [[pulmonary circulation]], may have also also been translated into Latin and available in Europe around that time, and that it may have had an influence on the descriptions of pulmonary circulation given by [[Michael Servetus]] (d. 1553) and [[Realdo Colombo]] (d. 1559), and possibly [[William Harvey]] (1578-1657).<ref>[http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/mon4.html Anatomy and Physiology], Islamic Medical Manuscripts, [[United States National Library of Medicine]].</ref> |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis’ mastery of medical sciences, his prolific writings, and also his image as a devout religious scholar left a positive impression on later Muslim biographers and historians, even among conservative ones like [[al-Dhahabi]]. He had been described as the greatest physician of his time, with some even referring to him as "the second [[Ibn Sina]]".<ref name=":3">{{cite book|last1=Freely|first1=John|title=Light from the East: How the Science of Medieval Islam Helped to Shape the Western World|date=2015|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=978-1-78453-138-6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JNQZCAAAQBAJ&q=%22the+second+Ibn+Sina%22&pg=PA100|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Numbers|first1=Ronald L.|title=Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion|date=2009|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-05439-4|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RC9Gm1V98OIC&q=%22the+second+Ibn+Sina%22&pg=PA39|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

Years before Ibn al-Nafis was born, Galenic [[physiology]] and [[anatomy]] dominated the Arabic medical tradition from the time of [[Hunayn ibn Ishaq]] (AD 809–873).<ref name="IBN AL-NAFĪS AND PULMONARY TRANSIT" /> Medical authorities at the time seldom challenged the underlying principles of this system.<ref name="IBN AL-NAFĪS AND PULMONARY TRANSIT" /> What set Al-Nafis apart as a physician was his boldness in challenging Galen's work. In studying yet criticizing the Galenic system, he formed his own medical hypotheses. |

|||

He also wrote a number of commentaries on the topic of medicine. His commentaries include one on [[Hippocrates]]' book, and several volumes on [[Avicenna|Ibn Sina]]'s ''[[The Canon of Medicine|Qanun Fil Tibb]]'' (''The Canon of Medicine''). Additionally, he wrote a commentary on [[Hunayn ibn Ishaq]]'s book. |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis importance in the history of medicine was not fully recognized in the western circles until quite recently. The majority of his works remained unknown in the west until their re-discovery at the beginning of the 20th century. Since then, a new evaluation of his work has been carried out, with a specific appreciation being given to his physiological observations which were ahead of their time. |

|||

==''Theologus Autodidactus''== |

|||

''Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah'' (''The Treatise of Kamil on the Prophet's Biography''), also known as ''Risālat Fād il ibn Nātiq'' (''The Book of Fādil ibn Nātiq''), was a work of [[Arabic literature|Arabic fiction]] written by Ibn al-Nafis and later translated into English as ''Theologus Autodidactus''.<ref name=Roubi>Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", ''Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ([[cf.]] [http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drroubi.html Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher], ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World'').</ref> |

|||

For science historians, Ibn al-Nafis is sometimes regarded as "the greatest physiologist of the Middle Ages".<ref>{{cite book|last1=Al-Khalili|first1=Jim|title=The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance|date=2011|publisher=Penguin|isbn=978-1-101-47623-9|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aJ5zDM1KfewC&q=%22greatest+physiologist+of+the+middle+ages%22&pg=PT144|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Meade|first1=Richard Hardaway|title=An introduction to the history of general surgery|date=1968|publisher=Saunders|isbn=978-0-7216-6235-0|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DGNsAAAAMAAJ&q=%22greatest+physiologist+of+the+middle+ages%22|language=en}}</ref> [[George Sarton]], in his "Introduction to the History of Science", written about the time Ibn al-Nafis's theory had just been discovered, said: |

|||

===Plot=== |

|||

<blockquote>If the authenticity of Ibn al-Nafis' theory is confirmed his importance will increase enormously; for he must then be considered one of the main forerunners of William Harvey and the greatest physiologist of the Middle Ages.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Pickthall|first1=Marmaduke William|last2=Asad|first2=Muhammad|title=Islamic Culture|date=1971|publisher=Islamic Culture Board|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RYYSAAAAIAAJ&q=%22If+the+authenticity+of+Ibn+al-Nafis%27+theory+is+confirmed%22|language=en}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

This was the earliest example of a [[desert island]] story, a [[coming of age]] story, and a [[science fiction]] story. The [[protagonist]] of the story is Kamil, a [[Abiogenesis|spontaneously generated]] and [[Autodidacticism|autodidactic]] adolescent living in seclusion on a deserted island, who eventually comes in contact with the outside world after the arrival of visitors who get stranded on the island and later take him back to the [[Civilization|civilized world]] with them. The plot gradually develops and eventually reaches its [[Climax (narrative)|climax]] with a catastrophic [[Eschatology|doomsday]] [[apocalypse]].<ref name=Roubi/> |

|||

== |

== See also == |

||

{{Portal|Biography|Islam}} |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis uses this story to express many of his own religious and philosophical views on a wide variety of subjects, including [[biology]], [[cosmology]], [[empiricism]], [[epistemology]], [[experiment]]ation, [[futurology]], [[geology]], [[natural philosophy]], the [[philosophy of history]] and [[sociology]], the [[philosophy of religion]], [[physiology]], and [[teleology]]. Through the story of Kamil, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to establish that the human [[mind]] is capable of [[Deductive reasoning|deducing]] the natural, philosophical and religious [[truth]]s of the universe through [[reasoning]] and [[Logic in Islamic philosophy|logical thinking]]. The "truths" presented in the story include the necessity of [[God]]'s existence, the life and teachings of the [[prophets of Islam]], and an analysis of the past, present, and future, including the origins of the [[Human|Homo Sapien]] species and a general [[Futurology|prediction of the future]] on the basis of [[historicism]] and historical [[determinism]]. The final two chapters of the story resemble a science fiction plot, where the [[Islamic eschatology|end of the world, doomsday]], [[Qiyamah|resurrection]] and [[Akhirah|afterlife]] are predicted and scientifically explained using the knowledge of [[Islamic medicine|biology]], [[Islamic astronomy|astronomy, cosmology]] and [[Islamic science|geology]] known in his time. The main purpose behind ''Theologus Autodidactus'' was to explain Islamic religious teachings in terms of [[Islamic science|science]] and philosophy through the use of a fictional narrative, hence this was an attempt at reconciling reason with revelation and blurring the line between the two.<ref name=Roubi/> |

|||

* [[List of Arab scientists and scholars]] |

|||

* [[List of Ash'aris and Maturidis]] |

|||

* [[Medicine in medieval Islam]] |

|||

* [[Theologus Autodidactus]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis described the book as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of Prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world." It presents rational arguments for bodily [[resurrection]] and the [[immortality]] of the human [[soul]], using both demonstrative [[reasoning]] and material from the hadith corpus as forms of [[evidence]]. Later Islamic scholars viewed this work as a response to [[Avicenna]]'s [[Metaphysics|metaphysical]] view of [[spirit]]ual resurrection (as opposed to bodily resurrection), which was earlier criticized by [[al-Ghazali]].<ref>Fancy, p. 42 & 60</ref> |

|||

=== Citations === |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

=== |

=== Sources === |

||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

The ''Theologus Autodidactus'' also contains some passages that are of significance to [[physiology]] and [[biology]], such as the following statement:<ref name=Roubi/> |

|||

==== Works cited ==== |

|||

{{quote|"Both the body and its parts are in a continuous state of dissolution and [[Nutrition|nourishment]], so they are inevitably undergoing permanent change."}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | author = Bayon H. P. | year = 1941 | title = Significance of the demonstration of the Harveyan circulation by experimental tests | journal = Isis | volume = 33 | issue = 4| pages = 443–53 | doi = 10.1086/358600 | s2cid = 145051465 }} |

|||

==== General references ==== |

|||

This is seen as the first example of the concept of [[metabolism]], which is comprised of [[catabolism]], where [[Tissue (biology)|living matter]] is broken down into simple [[Chemical substance|substances]], and [[anabolism]], where [[food]] builds up into living matter.<ref name=Roubi/> |

|||

* {{cite thesis |type = Ph.D. |title = Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288) |url = http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615/ |last = Fancy |first = Nahyan |year = 2006 |publisher = University of Notre Dame |access-date = 8 October 2012 |archive-date = 4 April 2015 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150404020329/http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615/ |url-status = dead }} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

|last=Iskandar |

|||

|first=Albert Z. |

|||

|year=1974 |

|||

|title=Dictionary of Scientific Biography |

|||

|volume=9 |

|||

|pages=602–06 |

|||

|title-link=Dictionary of Scientific Biography |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |title=Knowledge of the circulation of the blood from Antiquity down to Ibn al-Nafis |last=Said |first=Hakim Mohammed |date=1994 |journal=Hamdard Medicus |volume=37 |issue=1 |pages=5–37 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |title=Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the Scholars of the European Renaissance? |last=Ghalioungui |first=P. |date=1983 |journal=Clio Medica |volume=18 |issue=1–4 |pages=37–42 |pmid=6085974 }} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

* {{TDV Encyclopedia of Islam |last1=Kahya |first1=Esin |title=İBNÜ’n-NEFÎS |pages=173-176 |volume=21 |url=https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/ibnun-nefis}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{Wikisourcelang|ar|مؤلف:ابن النفيس|Ibn al-Nafis}} |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia | last = Iskandar | first = Albert Z. | title=Ibn Al-Nafīs, 'Alā' Al-Dīn Abu 'L-Ḥasan 'Alī Ibn Abi 'L-Ḥazm Al-Qurashī (or Al-Qarashī) | url = http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830903101.html | encyclopedia = [[Dictionary of Scientific Biography|Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography]] | publisher = Encyclopedia.com | orig-year=1970–80 | year = 2008 }} |

|||

*{{cite journal |last1=B.West |first1=John |title=Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age |journal=[[Journal of Applied Physiology]] |date=1 December 2008 |url=https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008 |access-date=1 December 2023}} |

|||

{{Clear}} |

|||

==Other subjects== |

|||

{{Islamic medicine}} |

|||

===Linguistics=== |

|||

{{Arabic literature}} |

|||

Ibn al-Nafis wrote two books on [[Arabic grammar|Arabic linguistics]]. One was his original work, ''Tareeq al-Fasaha'' (''Road to Eloquence''), while the other was a commentary on the linguist Said bin al-Hassan al-Rab'i al-[[Baghdadi]]'s ''Al-Fusous'' (''The Segments'').<ref name=Roubi/> |

|||

{{Shafi'i scholars}} |

|||

{{Ash'ari}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

===Logic=== |

|||