Beatus (book illumination)

Beatus Apocalypses , also known as Beatus manuscripts or Beatus for short , are illuminated manuscripts with a comment on the apocalypses ascribed to Beatus von Liébana . Most of the Beatus manuscripts originated in northern Spain between the 10th and 12th centuries.

26 illuminated manuscripts as well as some pure text manuscripts have been preserved in whole or in part. The extensive, large-format codices with their numerous colorful miniatures (a complete Beatus contains over 100) are among the most important masterpieces of Spanish illumination and have been part of the world's document heritage since 2015 .

Origin and use

The older surviving Beatus Codices all come from the Christian north of the Iberian Peninsula, especially from the Kingdom of León . Manufacturers and clients were almost exclusively to be found in monasteries.

The Beatus Apocalypse was not used in the liturgy, it was mainly used for private devotion and edification by monks. The scratched eyes and faces of the devil or the whore Babylon , which can be found in some manuscripts, testify to the profound impression on the believing reader .

Some of the splendid codices are likely to have served as prestige objects and status symbols and have been rarely read: They show little signs of use ( glosses , marginal notes) and are in excellent condition.

content

The Beatus manuscripts contain the following collection of texts with slight variations:

- Genealogical tables;

- Preface ( Praefatio ) with a dedication to Etherius by El Burgo de Osma ;

- Two prologues attributed to Saint Jerome ;

- The Interpretatio , a short commentary on selected sections of the Apocalypse;

- The main part, the Commentarius in Apocalypsin , divided into twelve books ;

- The Explicit , in which the components of a book (Codex) are enumerated (according to Isidore von Sevilla , Etymologiae VI 13, 1-2; 14, 6 );

- The treatises De adfinitates et gradibus and De agnatis et cognatis with definitions of relationships ( Etymologiae IX 5-6 );

- The Commentarius of Jerome to the book Daniel

How this combination of texts came about, the context of which is not always obvious, is unknown.

The Apocalypse Commentary by Beatus von Liébana

The attribution of the anonymously handed down comment to Beatus von Liébana is undisputed: It results from the dedication to the Beatus student Etherius and from the stylistic and content-related proximity to the pamphlet Adversus Elipandum .

In the preface Beatus calls his sources: Jerome, Augustine , Ambrose , Fulgentius , Gregory , Tyconius , Irenaeus , Apringius of Beja and Isidore. The Beatus' own contribution is small; his work is essentially a compilation of works by the authors mentioned. The vast majority - almost half - comes from the Apocalypse Commentary by Tyconius, a Donatist who lived in North Africa in the 4th century.

The division into twelve books probably comes from Tyconius. The text of the Apocalypse is divided into 66 sections called storiae . Each storia is followed by an explanatio , which is introduced with the words incipit explanatio suprascriptae storiae and verse by verse comments on the revelation text . The rambling work comprises more than 500 pages in a modern print edition. The date of origin is assumed to be the end of the 8th century (around 786).

style

In the isolated Christian kingdoms of the northern Iberian Peninsula, art forms have developed that clearly stand out from the other European art styles, even if various influences can be proven: some of these go back to antiquity; Suggestions were adopted from the neighboring Franconian Empire and above all from the Arab region, the latter probably conveyed by Mozarabic refugees.

Characteristic are the lack of naturalness and extreme stylization: Mountains are shown as simple geometric figures, for example, often just simple semicircles drawn with a compass. There is no space; the representations are purely two-dimensional. This contrasts with rich ornamentation; The artistic wickerwork is particularly remarkable. The colors are usually strong and bright.

A separate written form has also developed on the northern Iberian Peninsula, the Visigoth minuscule , in which all older Beatus codices are written.

iconography

Presumably, Beatus' commentary on the Apocalypses was designed as an illustrated work from the start. Over the centuries, the image program has seen various additions and extensions, but has not changed significantly. On the basis of iconographic , stylistic and textual features, several authors have proposed classifications and stemmas for the Beatus Codices, including Wilhelm Neuss , Henry A. Sanders, Peter K. Klein and John Williams. The results differ in some details; What they all have in common, however, is the division into two families, with family II being characterized by a richer illustration with more and larger miniatures. Within family II, a distinction is made between branches IIa and IIb.

Introduction pictures

The manuscripts differ most in the illustrations before the actual Beatus Apocalypse; quite a few pictures appear in just one handwriting. Several codices have the following miniatures in common:

- Labyrinth : Letter labyrinths can be found in numerous Spanish manuscripts from the High Middle Ages, not just in Beatus Codices. Boxes with letters are arranged in a - mostly rectangular and richly decorated - carpet. A short message is hidden in the frequently repeated letters, such as the place of manufacture, the scribe or client (e.g. S (an) c (t) i Micaeli lib (er) , "Book of St. Michael" in the Morgan Beatus) ).

- Maiestas Domini , Alpha and Omega

- Adoration of the Lamb and the Cross

- Evangelist cycle : This cycle of eight miniatures occurs only in family II. In a horseshoe-shaped arch there are two figures, on the left the evangelist with a witness, on the right two angels presenting the gospel. The symbols of the evangelists are shown above. Various models can be identified for this cycle, going back to early Christianity or even ancient times (portrait of the poet with his muse). The motivation for including the Evangelist cycle in a commentary on the apocalypses is unknown.

-

Genealogical tables : These can only be found in the Beatus of Family II. The family tree of Christ is presented on a total of seven double pages. The names are in circular medallions, other texts are framed by rectangles, circles and, above all, horseshoe-shaped arches. Several small miniatures illustrate the genealogy:

- Adam and Eve

- Noach ( Noe filus Lamech ): The illustration shows the burnt offering of Noach ( Gen 8.20 EU ) and marks the beginning of the second world age ( incipit secunda aetas mundi )

- Sacrifice of Isaac ( Gen 22 EU )

- World map: This simple Isidorian world map (see below) illustrates the division of the world between the three sons of Noah.

- Mary with the child

- The rare bird and the snake : The fight of the bird with the snake, which the one with the beak alone cannot win and wins with a blow with the tail, is interpreted Christologically.

Pictures of the Johannes Apocalypse

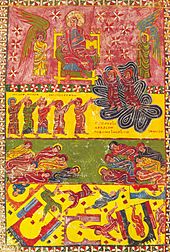

Most of the miniatures illustrate the apocalypse itself. The miniatures follow the text very literally, for example the sun and moon are divided into three almost equally sized sectors to illustrate the eclipse of a third ( Rev 8,12 EU ). But there is also some negligence, the symbol numbers (seven heads, ten horns, 24 elders, etc.) are not always correctly reproduced.

The people depicted, objects and scenes are almost always labeled, for example, John , angelus (angels), lapis (millstone, Rev 18.21 to 24 EU ), ubi John librum accepit (here John accepts the book Revelation 10,8- 10 EU ) etc.

The illustrations are usually located between storia and explanatio . Most of the Codices of Family II are full-page and framed. Smaller formats are also used, especially for the cycles (seven missions, seven trumpets, seven bowls); some miniatures are double-sided. Family II is also characterized by the monochrome horizontal stripes that form the background.

All the storiae illustrated in the Beatus manuscripts are listed below in full :

1st book:

- The revelation of God to John ( Rev 1,1-6 EU )

- The Lord appears in the clouds ( Rev 1 : 7-8 EU )

- Vision of the elder with the seven candlesticks ( Rev 1 : 10-20 EU )

2nd book:

- Letter to the seven congregations ( Rev 2 EU , 3 EU ): Cycle of seven similar, mostly smaller miniatures

3rd book:

- Vision of God on the throne; the twenty-four elders and the sea of glass ( Rev 4,1-6 EU )

- Vision of the Lamb, the four beings and the twenty-four elders ( Rev 5 EU )

4th book:

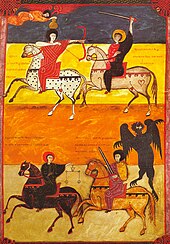

- The four horsemen of the apocalyptic ( Rev 6.1-8 EU )

- The altar and the souls of the deceased ( Rev 6,9-11 EU )

- The opening of the sixth seal ( Rev 6: 12-17 EU )

- The angels of the four winds ( Rev 7,1-8 EU )

- The Adoration of the Lamb and the 144,000 Sealed ( Rev 7,9-12 EU ) (mostly double-sided)

- The opening of the seventh seal ( Rev 8 : 1-6 EU )

5th book:

- The first five trumpets ( Rev 8,7 EU –9,6 EU ): cycle of five smaller miniatures

- The locusts and the angel of the abyss ( Rev 9: 7-12 EU )

- The sixth trumpet ( Rev 9: 13-16 EU )

- The vision of the riders ( Rev 9,17-21 EU )

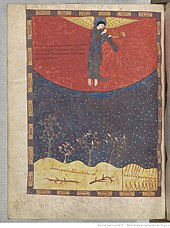

- The strong angel; John devours the book and measures the temple Rev. 10.1 EU –11.2 EU (John and the sea are outside the frame, so the miniature is larger than a page)

- The two witnesses ( Rev 11,3-8 EU )

- The Antichrist kills the two witnesses ( Rev 11 : 7-10 EU )

- Resurrection of the two witnesses; Earthquake ( Rev 11 : 11-13 EU )

- The seventh trumpet ( Rev 11.15 EU )

6th book:

- The opened temple and the beast from the abyss ( Rev 11:19 EU )

- The woman clad with the sun and the dragon ( Rev 12 EU ) (double-sided)

- The adoration of the beast and the dragon ( Rev 13 : 1-8 EU )

- The beast that comes up from the earth ( Rev 13 : 11-18 EU )

- The Lamb on Mount Zion ( Rev 14 : 1-5 EU )

7th book:

- The angel with the everlasting gospel and the fall of Babylon ( Rev 14 : 6-8 EU )

- Harvest and grape harvest; the winepress of God's wrath ( Rev 14 : 14-20 EU )

- The seven angels with the seven plagues and the Lamb ( Rev 15 : 1-4 EU )

- The seven angels with the seven bowls and the temple ( Rev 15,5-8 EU )

8th book:

- The seven angels with the seven bowls ( Rev 16,1 EU )

- The first six angels pour out their bowls ( Rev 16 : 2-12 EU ): cycle of six smaller miniatures

- From the mouths of the beast, the dragon and the false prophet, unclean spirits emerge like frogs ( Rev 16 : 13-14 EU )

- The seventh angel pours out his bowl ( Rev 16 : 17-21 EU )

9th book:

- The great whore and the kings of the earth ( Rev 17 : 1-2 EU )

- The woman on the scarlet beast ( Rev 17.3-13 EU )

- The lamb defeats the beast, the dragon and the false prophet ( Rev 17 : 14-18 EU )

10th book:

- The fall of Babylon; the lament of kings and merchants ( Rev 18 : 1-20 EU ) (unframed, one and a half pages)

- An angel throws the millstone into the sea ( Rev 18.21 EU )

- Appearance of God; Message to John ( Rev 19 : 1-10 EU )

11th book:

- The rider faithful and truthful ( Rev 19 : 11-16 EU )

- The angel in the sun and the birds ( Rev 19,17-18 EU )

- The killing of the beast and the false prophet ( Rev 19 : 19-21 EU )

- An angel binds the dragon for a thousand years ( Rev 20 : 1-3 EU )

- The souls of the righteous before God ( Rev 20: 4-6 EU )

- The rule of Satan ( Rev 20: 7-8 EU )

- The beast, the devil and the false prophet are thrown into the lake of burning sulfur ( Revelation 20: 9-10 EU )

12th book:

- The Last Judgment ( Rev 20: 11-16 EU ) (double-sided)

- Heavenly Jerusalem ( Rev 21 EU ) (unframed)

- The water of life and the trees of life ( Rev 22 : 1-5 EU )

- The angel rejects the worship of John ( Rev 22,6-10 EU )

Pictures to comment on the Beatus

Only a few miniatures illustrate the explanations of Beatus:

- World map : The vision of the seven candlesticks is followed by the extensive prologue of the second book ( De ecclesia et synagoga ), in which an insert deals with the twelve apostles and the countries and parts of the world that missionized them. In contrast to the small sketch of the world map in genealogy in some codices, this miniature fills two pages. The earth surrounded by the ocean is oval, from approximately circular (Beatus of Turin) to almost rectangular (Silos-Beatus, Beatus of Girona). The east ( oriens ) is at the top and contains a representation of the earthly paradise with the fall of man . On the right is the Red Sea , which is also painted in red; to the south (right) of this is the terra incognita , which is sometimespopulatedwith mythical creatures such as skiapods (e.g. Beatus von Burgo de Osma). At the bottom left is Europe, north of the stylized Mediterranean; to the right of this is Africa. Together with the so-called Vatican Isidorkarte ( BAV , Vat. Lat. 6018, f. 64v – 65r), the Beatus maps form the oldest records of the detailed medieval Mappae mundi.

- The four animals of Daniel : A section of the prologue De ecclesia et synagoga deals with the animal ( de bestia ) and quotes Jerome's commentary on the book of Daniel, in which the prophet's vision of the four animals ( Dan 7,3-8 EU ) is interpreted becomes.

- The statue with a golden head and feet of clay : Immediately afterwards, Nebuchadnezzar's dream is interpreted ( Dan 2,31-49 EU ).

- The woman on the beast : The same motif occurs again in the 9th book in the corresponding storia ( Rev 17.3-13 EU ).

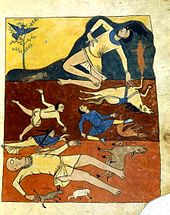

- Noah's Ark ( Gen 6 EU ): It illustrates the explanatio of the seven letters in which the question is discussed: Qualiter una ecclesia sit cum septem dicantur apertissime per arca Noe declaratur - How there is only one church, although there are seven is is best explained by Noah's ark. The text is based on the treatise De arca Noe by Gregory of Elvira . The ark is shown with four or five stories; on the lower floors are the animals, including sometimes mythical creatures such as unicorns. Noah is standing on the top floor holding the dove with the olive branch. Next to him are his wife, three sons and three daughters-in-law. A raven pecks at a drowned man.

- The palm of the righteous : The vision of the 144,000 sealed ( they stood in white robes before the throne and in front of the lamb and carried palm branches in their hands Rev 7,9 EU ) is an occasion for a longer digression about the palm as a symbol of the righteous (according to Gregory the Great, Moralia in Iob 6:49 ).

- The fox and the rooster : The explanatio of the animal that rises from the abyss compares the heretics with foxes that steal chickens. This little miniature can only be found in family II.

Images for the book of Daniel

The illustrations for the Book of Daniel are unframed in all manuscripts, including those of Family II.

- Frontispiece: Babylon surrounded by snakes

- The siege of Jerusalem ( Dan 1 EU )

- The dream of Nebuchadnezzar and the statue with the feet of clay ( Dan 2,24-36 EU )

- The adoration of the golden statue and the young men in the fiery furnace ( Dan 3 EU )

- The Banquet of Belshazzar ( Dan 5 EU )

- Daniel in the lions' den ( Dan 6 EU )

- Vision of the very old and the four animals from the sea ( Dan 7 EU )

- Susa Castle, the duel between a ram and a billy goat ( Dan 8,1-10 EU )

- Gabriel explains Daniel's vision ( Dan 8.15 EU )

- Daniel and the angel on the banks of the Tigris ( Dan 10.4-6 EU )

Beatus manuscripts up to 1100

The older Beatus manuscripts all come from the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula and are written in Visigoth minuscule; the only exception is the Beatus of Saint-Sever.

No uniform nomenclature has established itself in the literature. Beatus manuscripts are named after their scribe or illuminator, after the client, the place of origin or storage. A system of symbols was proposed by Neuss , which are given in square brackets below.

Single sheet from silos [Fc]

The oldest surviving fragment of a Beatus manuscript is now kept as fragment 4 in the Santo Domingo de Silos monastery , where it came from Cirueña in the 18th century . The original place of origin is unknown. The fragment is dated to the end of the 9th century. The small-format miniature of modest craftsmanship shows the altar and the souls of the deceased ( Rev 6,9-11 EU ).

Family I manuscripts

- Beatus von Madrid [A 1 ] ( Spanish National Library Vitr. 14-1), middle of the 10th century.

- Beatus of San Millán de la Cogolla [A 2 ] (Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia, Cod. 33). The codex dates from the last quarter of the 10th century and was unfinished. It was added in the 12th century.

- Escorial Beatus [E] ( El Escorial , Biblioteca del Monasterio San Lorenzo el Real, Cod. & II. 5). The manuscript was created around the year 1000 in San Millán de la Cogolla.

- Beatus of Burgo de Osma [O] (Archives of the Cathedral of Burgo de Osma , Cod. 1). The codex was written in Sahagún in 1086 .

- Beatus of Geneva (Bibliothèque de Genève, Ms. lat. 357). This codex was made in the 11th century in southern Italy in the region of Benevento . It was unknown until recently and was only published after it was donated to the Geneva library in 2007 .

Morgan Beatus [M]

The Codex, MS 644 of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, is named after its place of storage. In an extensive colophon on f. 293 the scribe mentions his name in a play on words ( Maius quippe pusillus - Maius, the little one), the place ( cenobii summi Dei nuntii Micaelis arcangeli - the monastery of San Miguel de Escalada near León ), the person who commissioned him, Abbot Victor, and the year ( duo gemina ter terna centiese ter dena bina = 2 × 2 + 3 × 300 + 3 × 10 × 2 = 964). Since the time calculation used in Spain at that time differs by 38 years from the one used today, this would mean a date of origin of 926. In today's research, such an early date is almost ruled out for stylistic reasons. It is generally assumed that it originated around the middle of the 10th century, with various interpretations of the date of Maius being suggested.

The Morgan Beatus is the oldest surviving codex of family II (branch IIa). It is possible that the innovations in Family II can be traced back to Maius himself.

Beatus of Tábara [T]

In the Colophon of the Beatus of Tábara [T] (Madrid, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Cod. 1097B), the writer Emeterius mentions the death of his teacher Magius in 968. It is certain that this Magius is identical with Maius.

Beatus of Valladolid [V]

After its presumed place of origin, the monastery of Valcavado near Saldaña in the province of Palencia , this codex is also called "Beatus of Valcavado". Today it is kept in the Biblioteca Santa Cruz in Valladolid (MS 433) and belongs to the IIa family. An inscription on f. 3v reports that the manuscript began on June 8, 970 and was completed on September 8, 970. The monk Obeco was entrusted with the work by Abbot Sempronius.

Beatus of Girona [G]

This Beatus Codex dates from the second half of the 10th century and is now kept in the archives of the Girona Cathedral ( Archivo Capitular de Girona ms. 7 olim 41 ). It belongs to family IIb, but has a number of special features.

The scribe senior is on f. 283v called ( Senior presbiter scripsit ). The colophon on f. 284 names the client, the abbot Dominicus ( Dominicus abba liber fieri precipit ) and as illuminators the nun En and the presbyter Emeterius ( En depintrix et Dei aiutrix frater Emeterius et presbiter - En, painter and assistant of God; Emeterius, brother and presbyter). Occasionally the painter's name is also referred to as Ende, after the - probably wrong - department Ende pintrix . The colophon also names the year ( era millesima XIII = 1013), which corresponds to 975 according to today's calendar.

At the beginning, the manuscript contains a number of miniatures that do not appear in any other Beatus (except the Beatus of Turin). On ff. 3v – 4r there is a double-sided representation of the sky in six concentric circles. The genealogical tables are followed by a cycle of six full-page miniatures on the life of Christ, including the crucifixion and the descent into hell.

The cycle of the seven missives is also remarkable. The miniatures are full-page and unframed; the depictions of the six churches (the sheet with the church of Pergamon is missing) are varied and imaginative.

The colors appear pale and muted compared to the strong coloring of most of the family II manuscripts. Numerous miniatures are adorned with gold and silver.

The Beatus of Turin [Tu] ( Turin , Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, ms. Lat. 93, so-called I.II, 1), created around 1100, is a direct copy of the Beatus of Girona.

Beatus von Urgell [U]

This codex is kept in the Diocesan Museum of La Seu d'Urgell (Num. Inv. 501). It does not contain any references to the client, place of manufacture, writer or illuminator. It was probably made in the last quarter of the 10th century in the Kingdom of León and belongs to the IIa family. As early as 1147 it appears in an inventory of the cathedral of La Seu d'Urgell.

Facundus Beatus [J]

The Facundus Beatus is one of the best known and most magnificent Beatus manuscripts. In the letter labyrinth at the beginning, the clients are named, King Ferdinand I and Queen Sancha, after whom the codex is sometimes also called “Beatus des Ferdinand and Sancha”. It is the only Beatus that has been proven not to be intended for a monastery. A royal scriptorium in León is assumed to be the place of manufacture. The colophon (f. 317) names the scribe Facundus ( Facundus scripsit ) and the year ( up to quadragies et V post millesima , 2 × 40 + 5 + 1000 = 1085, according to our era 1047).

Today the manuscript is kept in the Spanish National Library (Vitr. 14-2). She is counted in the family IIa.

Umberto Eco published a monograph on the Codex. He is an important source of inspiration for the name of the rose , in which the miniature of the woman clad in the sun and the dragon play an important role.

Fanlo Beatus [FL]

Only seven pages of this Beatus have survived in a copy from the 17th century. The copy was painted by Vicente Juan de Lastanosa (1607–84) with watercolors on paper; the template was located in the Montearagón monastery in the province of Toledo . Together with other papers from the possession of Juan Francisco Andrés de Uztarroz (1606–53), an Aragonese historian friend of Lastanosa, the copy was acquired by the Pierpont Morgan Library in 1988, where it is now kept under the name M. 1079.

Lastanosa's copies are so detailed that numerous conclusions can be drawn about the original. It was most likely a direct copy of the Escorial Beatus [E] from the mid-11th century. The scribe Sancius (Sancho) calls himself in an acrostic ( Sancius notarius presbiter mementote ). The letter maze named the abbot Pantio as the client. This pantio is identified with the Bancio or Banzo, known from other sources, who was abbot of the Aragonese monastery of San Andrés de Fanlo from 1035 to 1070.

Beatus of Saint-Sever [S]

This codex was probably written around 1060 for the Abbey of Saint-Sever in Gascony , and it may also have been produced there. The letter maze on f. 1 names the client Gregorius abba [s] nobil [is] , which most likely means Gregorius Muntaner, who was abbot of Saint-Sever from 1028 to 1072. In a column in the genealogical tables (f. 6) a Stephanus Garsia Placidus has been immortalized, which could be one of the illuminators. The manuscript is kept in Paris in the Bibliothèque nationale (MS lat. 8878).

This Beatus Codex is remarkable in many ways: It is the only Beatus before 1100 that was written on the other side of the Pyrenees and is not written in Visigoth, but in Carolingian minuscule . It belongs to family I, but also contains miniatures that otherwise only appear in family II. In terms of style and content, there are considerable deviations from the Spanish models. The representation of people and animals is much more natural. It contains a number of miniatures that do not belong to Beatus' pictorial program, e.g. B. the depiction of two bald men pulling each other's beards while a woman looks on (f. 184).

Silos Beatus [D]

The Silos Beatus is the youngest of the Beatus Codices in traditional style and Visigoth minuscule. As can be seen from several colophons (f. 275v, 276, 277v), the text was completed by the scribes Dominicus and Munnius in April 1091, while the miniatures by the illuminator Peter were not completed until July 1, 1109. The work began under Abbot Fortunius of Santo Domingo de Silos; after his death it was continued under the abbots Nunnus and Johannes.

The manuscript belongs to family IIa. The first miniature is an extraordinary depiction of hell, in which a rich man ( dives ) and an indecent couple are tormented by several demons ( Atimos, Radamas, Beelzebub, Barabbas ).

Joseph Bonaparte acquired the manuscript when he was King of Spain. In 1840 he sold it to the British Museum , where it is now an add. MS 11695 is kept.

Later Beatus manuscripts

Towards the end of the eleventh century there were profound changes in the ecclesiastical and cultural life of the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula. The Visigothic liturgy that was valid up to now was replaced by the Roman rite , the Visigoth minuscule was replaced by the Carolingian minuscule after the council in 1090. Art and architecture also came closer to the Romanesque forms widespread in France .

The heyday of the Beatus manuscripts in the peculiarly Spanish (often - probably not quite correctly - called "Mozarabic") style was over. Up until the middle of the 13th century, a number of Beatus codices were written in Carolingian minuscule. The miniatures are mostly based on the pictorial program of earlier Beatus manuscripts, but show numerous stylistic features of Romanesque book illumination . Important of these codices are:

- Rylands-Beatus [R], also called Manchester-Beatus ( Manchester , John Rylands University Library Latin MS 8), approx. 1175,

- Cardeña-Beatus [Pc]: The manuscript was created around 1180 and is in collections in Madrid ( Museo Arqueológico Nacional and Colección Francisco de Zabálburu y Basabe), New York ( Metropolitan Museum of Art ) and Girona (Museu d'Art de Girona) scattered.

- The Beatus of Lorvão [L] was written in 1189 in the monastery of S. Mammas in Lorvão (Portugal) and is now kept in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo in Lisbon .

- The Arroyo-Beatus [Ar] (named after the Cistercian Abbey of San Andrés de Arroyo ) was made in the region of Burgos in the first half of the 13th century , possibly in the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña. Today it is partly in Paris (Bibliothèque nationale) and New York (Bernard H. Breslauer Collection).

aftermath

After 1250, the production of Beatus manuscripts seems to cease entirely. The aftereffects and influences on other works of art were also minor. For example, in the numerous splendid Gothic commentaries on the apocalypses, which were produced in England in the third quarter of the 13th century, only a few, if any, influences of the Beatus tradition can be identified.

In the 16th century, individual scholars showed historical and antiquarian interest in Beatus manuscripts, such as the humanist Ambrosio de Morales (1513–91) from Córdoba . Beginning with the work of Neuss and Montague Rhodes James , the Beatus Codices were carefully researched scientifically in the 20th century. The depiction of those drowned in the Flood in the Beatus of Saint-Sever influenced Picasso's famous painting Guernica . The widespread interest in apocalyptics towards the end of the 20th century also led to the great popularity of Beatus and numerous publications and facsimile editions.

Quote

“The theophany of the Spanish Apocalypse takes place in nowhere and everywhere. All individual phenomena are organized from the center - one can rightly address such a representation as an expression of a theocentric worldview. "

literature

- Claus Bernet : Beatus Apocalypses. Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-7392-4692-5 .

- Brigitte English: Ordo orbis terrae. The worldview in the Mappae mundi of the early and high Middle Ages. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003635-4 , p. 171 ff. And p. 259 ff.

- John Williams and Barbara A. Shailor: Beatus Apocalypse of the Pierpont Morgan Library. A major work of Spanish book illumination of the 10th century. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart and Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7630-1213-3

- Mireille Mentré: Spanish illumination of the Middle Ages. Wiesbaden 2006. ISBN 3-89500-196-1

- Joaquín Yarza Luaces: Beato de Liébana. Manuscritos iluminados . Moleiro, Barcelona 1998, ISBN 84-88526-39-3 (Spanish)

- John Williams: The Illustrated Beatus. A Corpus of Illustrations of the Commentary on the Apocalypse . Miller, London (English):

- Volume 1: Introduction . 1994, ISBN 0-905203-91-7

- Volume 2: The ninth and tenth centuries . 1994, ISBN 0-905203-92-5

- Volume 3: The tenth and eleventh centuries . 1998, ISBN 0-905203-93-3

- Volume 4: The eleventh and twelfth centuries . 2002, ISBN 0-905203-94-1

- Volume 5: The twelfth and thirteenth centuries . 2003, ISBN 0-905203-95-X

- Visions of the end of the world. Apocalypse facsimiles from the Detlef M. Noack collection , ed. v. Caroline Zöhl, Berlin 2010. ISBN 978-3-929619-59-1

- Wilhelm Neuss: The Catalan Bible illustration at the turn of the first millennium and the old Spanish illumination . Publications of the Romance Studies Foreign Institute of the Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelms-Universität Bonn. Volume 3. Bonn and Leipzig 1922

- Wilhelm Neuss: The Apocalypse of St. John in the old Spanish and old Christian Bible illustration . Munster 1931

Web links

- Ms. 33 Beato de San Millan de la Cogolla

- Ms. 33

- Ms. Cod. & II.5 Escorial Beatus of San Millán

- Ms 644 Morgan Beatus

- Ms 1097 B Beatus of San Salvador de Távara

- Ms. 433 Beatus of Valcavado

- Ms. 26 Urgell Beatus

- Ms. 7 Gerona Beatus (Girona Beatus)

- Vit. 14-1 Beati in Apocalipsin libri duodecim ( Emilianenses Codice )

- VITR 14.2 (pdf) Beato of Liébana: Codice of Fernando I and Dña. Sancha ( Facundo / Facundus )

- Ms. Add. 11695 Beatus of Santo Domingo de Silos

- Ms. lat. 357 Geneva Beatus

- MS 8 Rylands Beatus

Remarks

- ↑ Complete list, with the exception of the Beatus of Geneva, which was only discovered after its publication, at the beginning of each volume in J. Williams, The Illustrated Beatus

- ^ The Manuscripts of the Commentary to the Apocalypse (Beatus of Liébana) in the Iberian Tradition. UNESCO Memory of the World, accessed September 1, 2017 .

- ↑ Latin text of the Etymologiae Isidors

- ↑ Latin text of the Etymologiae Isidors

- ^ Eugenio Romero Pose (Ed.): Sancti Beati a Liebana Commentarius in Apocalypsin . Scriptores Graeci et Latini Consilio Academiae Lynceorum Editi, Typis Officinae Polygraphicae, Romae 1985

- ^ Yarza Luaces: Beato de Liébana , p. 42

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Neuss: The Apocalypse of John in the Old Spanish and Old Christian Bible Illustration . Munster 1931

- ^ Henry A. Sanders et al .: Beati in Apocalypsin libri duodecim. Codex gerundensis . Madrid 1975

- ↑ Peter K. Klein: The older Beatus Codex Vitr 14-1 of the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid. Studies of Beatus illustration and Spanish book illumination of the 10th century . Hildesheim - New York 1976

- ^ John Williams: The Illustrated Beatus

- ^ Brigitte English: Ordo orbis terrae. The worldview in the Mappae mundi of the early and high Middle Ages. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003635-4 , p. 193 ff. And p. 259 ff.

- ^ Yarza Luaces: Beato de Liébana , p. 69

- ↑ Paule Hochuli Dubuis and Isabelle Jeger: Bibliothèque de Genève, Ms. lat. 357

- ^ Gabriel Roura i Guibas and Carlos Miranda García-Tejedor: Beato de Liébana. Code de Girona . Moleiro editor, Barcelona 2003, ISBN 84-88526-84-9 (Spanish)

- ^ J. Williams, The Illustrated Beatus , Volume 3, p. 17

- ^ Umberto Eco: Beato di Liébana: Miniature del Beato de Fernando I y Sancha (Codice BN Madrid Vit. 14-2) . Parma, FM Ricci, 1973

- ^ J. Williams: The illustrated Beatus , Volume 3, p. 43

- ↑ Miguel C. Vivancos and Angélica Franco: Beato de Liebana. Codice del Monasterio de Santo Domingo de Silos . Moleiro, Barcelona 2003, ISBN 84-88526-76-8 (Spanish)

- ↑ So in the representation of the heavenly Jerusalem, f. 24v of the Trinity Apocalypse , Trinity College Library Ms. R. 16.2 (after Yarza Luaces, Beato de Liébana , p. 306)

- ^ J. Williams: The Illustrated Beatus. Volume 3, p. 35

- ↑ MR James: The Apocalypse in Art . London, Oxford University Press, 1931

- ^ Santiago Sebastián: El Guernica y otras obras de Picasso: Contextos iconográficos . Editum: Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia 1984, ISBN 84-86031-49-4 , p. 90 (Spanish, online at Google Books )

- ^ Peter K. Klein: Epilogue: the Saint-Sever Beatus, Picasso's Guernica and other modern paintings. In: The Saint-Sever Beatus and its influence on Picasso's Guernica , Patrimonio, Valencia 2012, ISBN 978-84-95061-42-3

- ↑ Otto Pächt: Illumination of the Middle Ages . Prestel, Munich 1984. ISBN 3-7913-0668-5 , p. 162