Conquest of Baghdad (1258)

| date | January 29, 1258 to February 10, 1258 |

|---|---|

| place | Baghdad |

| output | Mongol victory |

| consequences | Looting and destruction of Baghdad. End of the Abbasid caliphate. |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Hülegü |

Caliph al-Musta'sim |

| Troop strength | |

| 120,000 to 150,000 men (including 40,000+ Mongols , Georgian infantry , 12,000 Armenian cavalry , 1,000 Chinese artillery , and Turkish and Persian soldiers) |

50,000 men |

| losses | |

|

Not known, relatively low |

50,000 soldiers, |

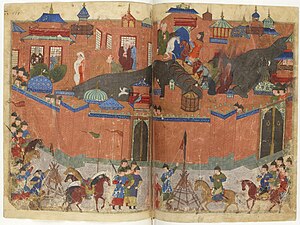

The Mongol conquest of Baghdad took place on February 10, 1258. The Mongols under Hülegü conquered and destroyed the capital of the Abbasid caliphs. Hülegü's goal was to bring the Middle East under firm control of the Mongol Empire. The caliph was actually supposed to serve as a vassal, but due to his refusal of allegiance, Hülegü was supposed to eliminate the Abbasids on the orders of the great khan Möngke .

After the siege and capture, Baghdad was totally destroyed. Estimates of civilian casualties range from 100,000 to one million. The city was looted and burned down. Cultural assets and libraries were destroyed. Remnants of the destruction were partly found in the river. As a result, Baghdad became meaningless for a long time and the capture of the city was seen as the end point of the heyday of Islam .

History and initial situation

The advance of the Mongols into the Middle East

The Mongols had conquered many countries in a short time and made them subject to tribute, and there was no end to their expansion in sight. The Mongol ruler Möngke Khan commissioned his brother Kublai with the conquest of China and his brother Hülegü with the conquest of the West after taking power . In Iran, the militant sect of the Assassins stood in the way of the Mongols . The assassins controlled several fortresses in the Elbors Mountains in northern Iran and Syria.

Hülegü was given a large army (one fifth of the entire army) for his campaigns. Every tenth warrior in the empire was to march with Hülegü, which probably corresponded to a strength of around 150,000 men. Hülegü set out in 1253 and reached Samarqand in Transoxania in 1255 due to the huge entourage . There he gathered all the vassals and sent more letters to other rulers who were to submit in order to go with him against the enemy.

In response to the Mongol invasion of Iran, the leader of the assassins in Alamut Ala ad-Din instructed Muhammad III. b. Hasan (ruled 1221–1255) assassin, Möngke Khan and the general Kitbukha to murder. But the project failed. Hülegü then attacked the assassins and was finally able to take Alamut on December 20, 1256 after the destruction of several fortresses. The castle was razed and the leader of the assassins - now Rukn ad-Din Churschah - was executed in 1257.

Diplomatic contacts between Mongols and Abbasids

The caliph an-Nāsir li-Dīn Allāh (r. 1180-1225) is said to have tried to ally with Genghis Khan against the threat from the Khorezm Shah Muhammad II . The caliph is said to have sent an embassy and possibly captured crusaders to the Mongols.

According to the Secret History of the Mongols , Genghis Khan and his successor Ögedei Khan are said to have given the order to attack Baghdad. In 1236 an army under General Chormaqan attacked the city of Erbil on the northern edge of the caliphate. Thereafter, the Mongols undertook raids against Erbil almost every year and came as far as the city walls of Baghdad. In 1238 and 1245 the Caliphate defeated divisions of the Mongols.

Despite these victories, the caliph hoped for an agreement with the Mongols and in 1241 sent them a great tribute. Envoys of the caliph attended the coronations of Güyük Khan in 1246 and Möngke Khan in 1251. Güyük Khan insisted that the caliph in person to Karakorum come and should be completely subdue the Mongols. Güyük Khan and Möngke Khan blamed the inability of Baiju - the successor of Chormaqan - for the resistance of the caliphate.

After the assassins were eliminated, Hülegü stayed in Hamadan. From there he sent letters to the incumbent caliph al-Musta'sim requesting that he submit to the Mongols as a vassal. The caliphs refused to follow the Mongols as early as 1232. Originally - according to Raschīd ad-Dīn - al-Musta'sim probably wanted to follow the wishes of the Mongols, but was changed by his advisors. Several people accused the caliph of incompetence and lack of competence. He misjudged the dangerous situation because, in contrast to earlier times, there was now a large army of conquest against the city.

Baghdad and the Abbasid Caliphate in the 13th century

In 751 the Abbasids overthrew the first Umayyad dynasty of Damascus , which had ruled the Arab Empire (Islamic Caliphate) since 661. The center of power shifted first from Arabia to Syria, then under the Abbasids to Mesopotamia. From around the middle of the 8th century, local rulers, who had previously administered the provinces under their control as governors on behalf of the caliph, became independent within the Islamic Caliphate (especially on the periphery of the empire) due to the weakness of the caliphs in Baghdad as sovereigns their own dynasties. The caliph had meanwhile become a puppet in the hands of his military slaves or warlords or foreign dynasties such as the Iranian Buyyids or Turkish Seljuks in the center of his empire , but still had great significance as a symbolic figure in the Islamic world. But from the 12th century, in the course of the decline of the Seljuks, the caliphs were able to regain more and more of their former power and acted more and more independently. In addition to their spiritual authority , they regained secular power in what is now Iraq.

At its peak, Baghdad had a population of nearly one million and was defended by 60,000 soldiers. It was the center of the Islamic world. But Baghdad was damaged by floods (1243, 1248, 1253, 1255, and worst of all, 1256) and fire, and the competition between Sunni Arab and Shiite Persian residents turned violent; nevertheless, the city was still rich and culturally important. The center of the city had shifted from the district capital of the city founder al-Mansur to the east, directly on the Tigris, where the new caliph's palace stood. This eastern part of Baghdad (al-Šarqiya) was more densely populated and home to the mostly Sunni Arabs. There were various mosques, palaces and gardens next to the caliph's palace. The neighborhood was surrounded by a wall. In the west (al-Ḡarbiya) mainly Shiites lived. East and West were only connected by two bridges. Many areas of the city lay fallow and desolate and were never rebuilt.

The siege

Hülegü's huge army consisted of three armies. The northern part under the command of Baijus came from Anatolia via Erbil and crossed the Tigris at Tikrit on January 16, 1258 and approached Baghdad from the west. Hülegü himself started with his army from Hamadan and came to Baghdad from the east via Kermanshah , Hulwan . The southern group moved towards Baghdad via Lorestan .

In Hülegü's army there were generals such as Arghun Aqa from the Oirats , Baiju, Buqa-Temur, the Chinese Guo Kan , the Jalaiyr Koke Ilge, Kitbukha from the Naimans , Tutar and Quli from the Golden Horde and Hülegü's brother Sunitai. In addition to the Mongols, large associations of Christian vassals such as the Georgians , Armenians and some Franks from the Principality of Antioch fought . The contemporary witness Ata al-Mulk Juwaini also reported on 1000 Chinese artillery experts, Persian and Turkish soldiers.

Al-Musta'sim failed to defend the city against the Mongols for several reasons: he neither enlisted additional men in the army, nor did he strengthen the defensive walls. Nor was he ready to leave Baghdad to the infidel barbarians. He also feared the massacres that the Mongols would commit if the city were surrendered. So he threatened Hülegü himself, who then decided to destroy the city.

Hülegü positioned his army on both sides of the Tigris and let them encircle the city like pincers. The caliph's army made a successful sortie with around 20,000 men and was able to bring substantial parts of the west bank under control again, but was then defeated in a second battle. The Mongols destroyed some of the upstream irrigation dykes and were able to cut off and encircle the troops from the main army in the city. Several thousand soldiers were killed or drowned, the rest managed to escape back to the city.

When the main Mongol army arrived, the siege of Baghdad began on January 22nd. A palisade and a trench were drawn around Baghdad and catapults and siege weapons were deployed. Using bricks from the abandoned suburbs, the Mongols built siege towers near the city walls from which they could shoot stones, incendiary devices and arrows over the walls. The river was blocked by pontoon bridges at the city entrance and exit. The attack on the city began a week later on January 29th. On February 5, the Mongols succeeded in opening a breach and in the ensuing assault they captured the entire eastern city wall. Al-Musta'sim's offer to negotiate was rejected. On February 10th (according to the Islamic calendar on 4th Safar 656 AH) he surrendered the city and on February 13th the Mongols poured into the city. A week of destruction and massacre began.

Destruction and massacre

After the Mongols entered the city, they wreaked havoc. The House of Wisdom , which contained countless valuable historical documents on subjects from medicine to astronomy, was destroyed. Survivors said the Tigris water was black from the ink. All other libraries in the city were burned, as well as mosques, palaces and hospitals. Scientists and philosophers were not spared. Citizens who wanted to flee were intercepted and killed by the Mongols. Martin Sicker speaks of almost 90,000 victims. Other estimates are higher. The 14th century historian of the Ilchane, Abdullah Wassaf, suspected several hundred thousand dead. Ian Frazier of The New Yorker estimates the number of victims between 200,000 and one million. Hülegü had to set up camp at another location because of the strong stench of putrefaction.

The caliph was captured and watched as its citizens were killed and its treasures looted. On February 20, Hülegü set out for Azerbaijan and had the caliph and his 23-year-old son killed on the way near a village east of the city. Most sources say that the caliph was trampled to death. For this he was wrapped in a carpet and rolled over by the riders. His noble blood should not anger the ground and conjure calamity. He was buried, but there are no traces of a grave. His youngest, 16-year-old son and three daughters were spared. The daughters were sent to Mongolia, where one daughter probably committed suicide on the way. The other two married and later returned to Baghdad with the permission of the Mongols. The son lived with the Mongols in Armenia, where he married and died in old age. The eldest son, who was 25 years old, died in town the day after his father.

Baghdad was largely depopulated and ruined. Little of its fame was regained for centuries. The chronicler Isuf al'Haita describes the Mongols as an "unstoppable sandstorm" that struck the city and "turned Baghdad into a deep red". A pyramid of skulls "higher [...] than all minarets and towers of the great city had ever been before" testified to the brutality of the destruction. Abdullah Wassaf reported in his work that the Mongols attacked the people of the city like raging wolves and hungry hawks, rampantly and shamelessly spreading murder and terror. The scientist Steven Dutch speaks of Baghdad as "one of the most brilliant intellectual centers in the world". The destruction of the city was "a psychological blow from which Islam never recovered". In addition, the looting "stifled the intellectual flourishing of Islam".

Despite these almost apocalyptic accounts, it should be noted that there have been other, far less cruel accounts. This can in part be justified by the fact that the Mamluk enemies of the Mongols exaggerated the Mongols' cruelty for propaganda reasons. This could be seen, for example, from the fact that the caliph's entire family had been executed. But the only two eyewitnesses who later wrote down the events - on the part of the Mongols Nasīr ad-Dīn at-Tūsī and on the side of the besieged Ibn al-Kazaruni - reported the killing of some family members, but no order to kill all Abbasids . As mentioned, some of his children survived and other family members continued to be among the city's notables. The destruction did not go beyond the usual destruction in the course of a siege, because the Mongols did not deal with Baghdad like z. B. with Bukhara , which was conquered in 1220 and whose entire population was either killed or deported.

Consequences and meaning

The end of the Baghdad Caliphate

Previous invaders had been absorbed and integrated into Baghdad's Muslim culture. But the Mongol conquest and destruction of Baghdad ended a period and was a trauma. The caliph was dead. The youngest son and three daughters were spared and married to nobles. Other surviving relatives of al-Musta'sim fled to the Muslim Egypt of the Mamluks. There a cousin of the last caliph named al-Mustansir II was appointed caliph by the Mamluk sultan. The Mamluks, who were later to stop the advance of the Mongols, blamed the Shiite vizier of the caliph for the downfall of the city. The vizier al-Alqami betrayed the caliph to the Mongols, but was also killed himself. Al-Mustansir tried to recapture Baghdad and set out from Damascus with a few hundred men in October 1261. The Mongols intercepted him on the banks of the Euphrates at the end of November and defeated him. Nothing is known about his fate, either he escaped and disappeared or he was killed. His successor was al-Hākim I. The Egyptian Abbasids were finally ousted by the Ottomans in the 16th century .

Baghdad under Mongol rule

The fall of Baghdad was a great shock to the Islamic world, but the city was rebuilt and later developed again into an international trading center, where coins were minted and the religion flourished among the Mongolian Ilkhan.

Hülegü returned to Azerbaijan and left 3,000 Mongolian warriors to rebuild the badly damaged Baghdad. Corpses and carcasses were removed and the markets reopened. Coins were minted again in the same year. The Christian residents of Baghdad had been spared at the request of their wife Hülegüs Doquz-Chatun , who was herself a Christian Nestorian . Hülegü offered the palace of the caliphs to the Nestorian patriarch Mar Makkicha II and ordered the construction of a cathedral. Baghdad was integrated into the Mongolian administrative system: Baghdad, southern Mesopotamia and Chusistan received a governor ( Wali ), a deputy governor ( Nāʾeb ), a military commander ( Šeḥna ) and several judges. Wali and Nāʾeb could also become natives, but a Mongol was always used as Šeḥna. Baghdad was even administered by two Welsh for a time. The scholar and teacher Hülegüs, Ata al-Mulk Dschuwaini, was appointed Nāʾeb in 1260, while the Wali of the entire region was the Mongol prince Sujunjāq, who usually left the administration to Juwaini. In 1258/59 a census and tax assessment was carried out in the city. The Jacobite traveler Gregorius Bar-Hebraeus visited Baghdad in 1265 and found that the Mongol conquest of Aleppo was more devastating than it was in Baghdad.

Agricultural decline in Iraq

Some historians believe that the Mongol invasion severely damaged the intricate and millennia-old irrigation system. Sewers were interrupted and destroyed and through the flight and death of countless people, there was no longer any possibility of repairing and maintaining the huge system. This marked the decline of agriculture and the expansion of the desert in Mesopotamia. This thesis was put forward by the historian Svatopluk Souček in his book A History of Inner Asia , published in 2000 . Other historians point to salinization as the main reason for the decline in agriculture.

Individual evidence

- ^ John Masson Smith, Jr .: Mongol Manpower and Persian Population , p. 276

- ↑ a b L. Venegoni: Hulagu's Campaign in the West - (1256-1260) , Transoxiana Webfestschrift Series I , Webfestschrift Marshak of 2003.

- ↑ a b c National Geographic , v. 191 (1997)

- ↑ John Masson Smith, Jr .: Mongol Manpower and Persian Population , pp. 271-299

- ↑ AY Al-Hassan (ed.): The different aspects of Islamic culture. Science and technology in Islam . Volume 4, Dergham sarl, 2001, p. 655.

- ↑ Peter Jackson: The Dissolution of the Mongol Empire , Central Asiatic Journal 32 (1978), pp. 186-243

- ↑ Matthew E. Falagas, Effie A. Zarkadoulia, George Samonis: Arab science in the golden age (750-1258 CE) and today . In: The FASEB Journal 20 , 2006, pp. 1581-1586.

- ↑ Jack Weatherford: Genghis Khan and the making of the modern world. ISBN 0-609-80964-4 , p. 135

- ^ Jack Weatherford: Genghis Khan and the making of the modern world , p. 136

- ↑ Sh. Gaadamba: Mongoliin nuuts tovchoo. Ulsyn Khėvlėliĭn Gazar, 1990, p. 233 (Mongolian)

- ↑ Timothy May: Chormaqan Noyan , p. 62

- ↑ a b C.P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire , p. 2

- ↑ Al-Sa'idi, op. Cit., Pp. 83, 84, from Ibn al-Fuwati

- ↑ Spuler, op.cit., From Ibn al-'Athir, vol. 12, p. 272.

- ↑ http://www.alhassanain.com/english/book/book/history_library/various_books/the_alleged_role_of_nasir_al_din_al_tusi_in_the_fall_of_baghdad/004.html

- ↑ Johannes de Plano Carpini : Ystoria Mongolorum quos nos Tartaros appelamus , ( English translation by Erik Hildinger from 1996 in the Google book search)

- ^ Daniel C. Waugh: The Mongols and the Silk Road, I. at depts.washington.edu

- ↑ Nicolle, p. 108

- ↑ a b Nicolle, p. 130

- ↑ Stefan Heidemann: Das Aleppiner Kaliphat , p. 44

- ↑ Raschīd ad-Dīn : Histoire des Mongols de la Perse , E. Quatrem "re ed. And trans. (Paris, 1836), p. 352.

- ↑ Demurger, pp. 80-81; Demurger p. 284

- ↑ a b Saunders, p. 110

- ↑ Nicolle, p. 132

- ^ Sicker, p. 111

- ^ Ian Frazier: Annals of history: Invaders: Destroying Baghdad , The New Yorker , April 25, 2005. p. 4

- ↑ Isuf al'Haita, chronicler: The destruction of Baghdad by the Mongol prince Chülegü (February 10, 1258) at another-view-on-history.de

- ↑ Steven Dutch: The Mongols ( Memento of the original from December 11, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. at www.uwgb.edu

- ^ Reuven Amitai Prize: Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 , p. 58

- ^ Richard Coke: Baghdad, the city of peace , p. 169

- ↑ Maalouf, p. 243

- ↑ Runciman, p. 306

- ↑ Foltz, p. 123

- ↑ Alltel.net ( Memento from July 12, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Saudiaramcoworld.com ( Memento of the original from January 25, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

literature

- Reuven Amitai Prize : Mongols and Mamluk. The Mamluk-Īlkhānid War, 1260-1281. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1995, ISBN 0-521-46226-6 .

- Alain Demurger: Les Templiers. Une chevalerie chrétienne au Moyen Âge. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-02-066941-2 .

- Alain Demurger: Croisades et Croisés au Moyen-Age (= Champs. Vol. 717). Groupe Flammarion, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-08-080137-6 .

- Hend Gilli-Elewy: Baghdad after the fall of the caliphate. The history of a province under Ilānian rule (656 - 735/1258 - 1335) (= Islamic studies. Vol. 231). Schwarz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-87997-284-2 (At the same time: Cologne, University, dissertation, 1998), digital version on the website of the University and State Library of Saxony-Anhalt .

- Stefan Heidemann: The Aleppine Caliphate (AD 1261). From the end of the caliphate in Baghdad via Aleppo to the restorations in Cairo (= Islamic History and Civilization. Vol. 6). Brill, Leiden u. a. 1994, ISBN 90-04-10031-8 (also: Berlin, Freie Universität, dissertation, 1993), ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- Aptin Khanbaghi: The fire, the star, and the cross. Minority religions in medieval and early modern Iran (= International Library of Iranian Studies. Vol. 5). IB Tauris, London a. a. 2006, ISBN 1-84511-056-0 .

- David Morgan: The Mongols. Blackwell, Oxford, et al. a. 1990, ISBN 0-631-17563-6 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- David Nicolle : The Mongol Warlords. Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. Illustrated by Richard Hook. Brockhampton Press, London 2004, ISBN 1-86019-407-9 .

- Steven Runciman : History of the Crusades. Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39960-6 .

- John J. Saunders: The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia PA 2001, ISBN 0-8122-1766-7 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Martin Sicker: The Islamic World in Ascendancy. From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Praeger, Westport CT et al. a. 2000, ISBN 0-275-96892-8 .

- Svat Soucek: A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2000, ISBN 0-521-65704-0 .

- Bertold Spuler : The Mongols in Iran. Politics, administration and culture of the Ilchan period 1220–1350. 4th, improved and enlarged edition. Brill, Leiden 1985, ISBN 90-04-07099-0 ( limited preview in Google book search).

Web links

- ʿAbbās Zaryāb: Baghdad from the Mongol conquest to the Ottomans . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of: August 22, 2011 (English, including references)

- Annals of History -Invaders -Destroying Baghdad , article by Ian Frazier, April 25, 2005 in The New Yorker