Bentresch stele

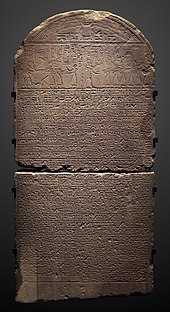

| Bentresch stele | |

|---|---|

| material | Sandstone |

| Dimensions | H. 227 cm; W. 106 cm; D. 14 cm; |

| origin | Luxor , Karnak Temple , near the Chons Temple |

| time | Late period or Ptolemaic period |

| place | Paris , Louvre , C 284 |

The Bentresch stele (also Bachtan stele or Bachtan stele ) is a stele from ancient Egypt that was found in the Karnak Temple in Luxor in 1828 and is now in the Louvre in Paris . It presents itself as a historical-religious monument from the time of King ( Pharaoh ) Ramses II (ruled approx. 1279 to 1213 BC), but has enough features that justify classification as an ancient Egyptian literary work . The late period (664 to 332 BC) or Ptolemaic period (332 to 30 BC) is assumed to be the time of origin . The inscription is in hieroglyphic script and "neo-Middle Egyptian" language, a form of language that uses the "classical", Middle Egyptian structure and orthography, but is influenced by later language levels.

The stele tells of an Egyptian king who marries a princess from Bechten (a fictional city in the Middle East). When their sister Bentresch is attacked by a demon , the Egyptian king sends a statue of a god to drive him out. After successful treatment, the King of Bechten initially does not want to send the statue back, and only after a nightmare does he change his mind.

Ramses II's wedding steles, reports about Egyptian doctors abroad and probably the abduction of Egyptian statues of gods during the Persian rule served as historical models. The text may have been written to show the superiority of Egyptian gods abroad, or to process historical knowledge from a time when Egypt was still a great power.

The stele has also attracted attention outside of Egyptology as a source of the exorcism phenomenon .

Description and dating

The Bentresch stele comes from the Karnak temple ( Amun district ) in Luxor, where it was found in 1828 in architectural remains from the Greco-Roman period in the vicinity of the Chons temple . It passed into the possession of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris in 1844 and is now in the Louvre in Paris and bears the inventory number C 284. The 2.27 m high and 1.06 m wide sandstone stele with a round top contains below the image the winged sun disk and an image field an inscription in 28 lines. The text was written in left-handed hieroglyphic script and neo- Middle Egyptian language level . The basic pattern of the sentence structures are similar to the conditions in central Egypt. There are also numerous phenomena that show the influence of later language levels ( New Egyptian , Early Demotic ), and the orthography shows peculiarities with a fundamental tendency towards historical graphics, which suggest that the phonetic realization of the text after the middle of the first millennium v. Valid rules took place.

The stele itself gives the impression that it dates from the time of Ramses II, as the cartouches of this king appear six times. With these, however, elements of the name of Thutmose IV are mixed up, which in addition to epigraphic , linguistic and iconographic criteria is a further clue for a later date of origin. Georges Posener assumes the first Persian rule as the time of origin and Frank Kammerzell in general the late period , while Wilhelm Spiegelberg and Sergio Donadoni assume the Ptolemaic period .

Other fragments of a copy of this text have recently been found in Luxor. For paleographical reasons these date back to the 30th Dynasty, but have not yet been published.

content

Gable fields

The upper part of the rounded gable is crowned by Behdeti as a winged sun disk. In the illustration in the lower right field, twelve priests carry the barque of Chons -in-Thebes-Neferhotep. Before that, the Egyptian king offers his father Chon's incense. Above it flies the vulture-shaped goddess Courage , who ensures that "he is given all conceivable protective measures for his life." which is carried by four priests.

inscription

At the beginning, the inscription describes in detail the title, name and epithets of an Egyptian king who, at first glance, is Ramses II . During a stay of this king in Naharina (in the northern Syrian region around Karkemiš ) to receive tribute deliveries from the princes of the surrounding countries , the king of Bechten presented him with his eldest daughter as a consort as a special sign of favor. The Egyptian king finds her beyond measure enchanting, immediately raises her to the rank of royal main wife and gives her the Egyptian name Neferu-Ra.

A few years later, a messenger from the King of Bechten comes to the court of the Egyptian king and reports that Neferu-Ra's younger sister Bentresch has an illness and asks for help. After consulting the court (in the style of the king's novella ), a royal scribe named Djehutiemheb is sent to Bechten as a doctor. For the time being, he can only make the diagnosis that Bentresch is attacked by a demon that has to be fought. The king of Bechten then asks the Egyptian king to send an image of a god. After consulting the god Chons -in-Theben-Neferhotep, the god Chons-the-plan-maker-from-Thebes, “the great god who casts out the demons of disease”, is sent to Bechten in the form of his god statue.

With it the Egyptian doctor Djehutiemheb can perform a protective spell for Bentresch and heal her immediately ( exorcism ). The demon that resided in Bentresch now speaks to Chons-the-plan-maker-from-Thebes:

“Welcome, you mighty God who casts out the demons of disease. Your city is to rule, its people are your subordinates, and I too am your servant. I'll be going back where I came from to make sure you can be satisfied because that's what you came for after all. May your Highness make arrangements to make you a pleasant day with me and with the King of Bechten. "

Chons-der-Plänemacher-aus-Thebes demands that the king of Bechten prepare a rich sacrifice for the demon. At first he was frightened, but then made a rich sacrifice. The demon then withdraws to a peaceful place at the behest of the Chons-des-Plänemacher-von-Thebes and the king of Bechten is in a relaxed mood with all of Bechten's inhabitants.

Later, the king of Bechten secretly plans to keep the Egyptian god with him and not send it back to Egypt, whereby the god remains there for three years and nine months. In a nightmare, however, the King of Bechten sees the god emerge from his shrine in the form of a golden falcon to fly off towards Egypt. He then immediately sends him back to Egypt equipped with valuable gifts, where he arrives safely in the end.

Historical role models

Ramses II wedding steles

The wedding steles of Ramses II certainly served as a historical model for the Bentresch stele . A wedding stele was attached to the facade of the great temple of Abu Simbel , a detailed and an abbreviated version of it were also set up in the Karnak temple, with which the author of the Bentresch stele should have known the content. The wedding steles tell of the wedding of Ramses II with the Hittite princess Sauškanu , daughter of King Hattušili III. , which was given the Egyptian name Maat-Hor-Neferu-Re .

Hattušili III. had proposed marriage to his daughter in the year of death of the great royal wife Isisnofret in order to deepen the alliance between the two countries. Long negotiations about the bride price had taken place beforehand. If in the past foreign princesses only rose to the rank of concubine , it was agreed in the contractual terms between Hatti and Egypt that Sauškanu should be the first foreign princess to receive the title of Great Royal Wife .

Ramses II did not mention the contractual clauses on the stele in Abu Simbel , but presented the situation differently:

“Hattušili III. and Puduhepa gave their eldest daughter as an honorable gift to the living God so that he might give them peace and they can live in peace. "

The name Maat-Hor-Neferu-Re clearly refers to the name Neferu-Ra of the Bentresch stele. S. Morschauser was also able to show further terminological references to these two steles. There is also evidence of a king's scribe with the name Djehutiemheb at the time of Ramses II.

Egyptian doctors abroad

Egyptian doctors had a good reputation throughout the ancient world. For example, Homer in the Odyssey , Herodotus in his Histories and Diodorus in his Universal History made very positive comments about the Egyptian doctors. A representation in Nebamun's tomb at the time of Amenophis II (14th century BC) suggests that a Syrian prince was treated by Nebamun, the personal physician of the Egyptian king. A few decades later, the king of Ugarit Akhenaten asked for a palace doctor. From cuneiform letters it is known that the Hittite king Hattušili III. Ramses II asked several times for medical help from Egypt. Once Ramses II sent a doctor and an incantation priest to drive out a disease demon. For the time thereafter, there is no evidence of Egyptian doctors abroad until the first Persian rule. During the Persian rule, Egyptian doctors stayed at the Persian royal court more often, as reported by Egyptian and Greek sources.

Abducted statues of gods

In the Persian Wars in particular, it seems to have been a common occurrence that images of gods were stolen during the war campaigns. For example, some decrees of the first Ptolemies (for example the satrap stele) report the repatriation of statues which the Persians had abducted. In the commentary of St. Jerome to Daniel XI, 7-9, in the same context, 2500 images of gods and cult objects are mentioned, whereby it is expressly noted that among these there were also those who abducted Cambyses to Persia. For the Ptolemaic period and the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great , based on the decrees, it can be assumed that no statues of gods were kidnapped. For this reason Morschauser dates the Bentresch stele to the Persian period, but does not make any further delimitation with regard to the first or second Persian rule.

Interpretations

Michèle Broze has shown in her stylistic analysis that the text was composed very carefully and also worked out the status, meaning and character of the individual persons. First of all, the King of Bechten acts as a mastermind and disobeys the Pharaoh and the Egyptian god. In the end, the relationship turns and the god is the real actor, whom the king of Bechten now has to obey. The god and the priest ultimately have the decisive role in this story, one in the capacity of an invisible power, the other in the capacity of mediator of this power. This means that nothing can happen effectively without the priest.

Scott Morschauser interprets the stele as an encrypted document of the priestly resistance against Persian rule. This is related to the deportation of images of gods from Egypt and their later repatriation and emphasizes that the Egyptian gods are ultimately superior. Günter Burkard also largely follows this interpretation:

“A text that was intended to emphasize the superiority of the Egyptian gods, a document of resistance against foreign rule, which, thanks to the encryption, which is not accessible to everyone, especially not to the Persian masters, could be set up in public, apparently also in several Copies. This thought seems to me as captivating as it is convincing. "

According to Frank Kammerzell, the fall of the great power Egypt at the end of the New Kingdom created texts that deal with the past and the present. The contrast between the “glorious” past remembered in historical tradition, literature, religion and art and the contemporary conditions must have had a sobering effect on certain groups in Egyptian society. In these texts, historical knowledge, for example about Egyptian doctors abroad or international marriages, is processed, which has been passed down like a mosaic in the existing monuments:

“Accordingly, the stele text should be seen as a work of literature that narrative links remembered fragments of a past reality and thus designs a fictional world as a projection of the contemporary real world. The modeling is done in such a way that the literary ruler acts according to his historical models, while the stage of the action is adapted to the changed worldview: the pharaoh of the Bentresch stele is not only a "composite personality" in terms of his actions, but becomes through his name explicitly introduced as such, and the region around Karkemish does not mark the outermost limit of (temporary) Egyptian influence, but is the center of action from which the power of Pharaoh radiates into incredible distances. "

exorcism

Outside of Egyptology, the Bentresch stele was especially noted as a source for the description of the exorcism phenomenon, for example in connection with Matthew 8: 28-34 (“Healing of the two possessed Gadarenes” Matt 8 : 28-34 EU ). The term 3ḫw is used here like a word for “demon”, but for Morschauser it seems to be more of a lower deity who is offered together with Chon's sacrifice and who is allowed to return to her whereabouts. Therefore, the text has already been interpreted in such a way that it describes the triumph of an Egyptian god over an Asian demon, but the attitude of the Egyptian god towards the "demon" appears surprisingly tolerant and the exorcism is rather non-violent, with no evidence of apotropaic rites . It is the result of a negotiation in which the Egyptian god grants the demon "official" recognition and lets him return to a place of residence. The demon is indisputably the cause of Bentresch's illness. He recognizes the sovereignty of the healer, but can negotiate something similar to the healing of the two possessed Gadarenes through Jesus. The practice of dialogue may even originate in Egypt.

literature

Editions

- Jean-François Champollion : Monuments de l'Égypte et de la Nubie. Notices descriptives conformes aux manuscrits autographes rédigés sur les lieux. Volume 2: Livre 11/19. Firmin Didot, Paris 1844, pp. 280-290.

- KA Kitchen : Ramesside Inscriptions. Historical and Biographical. Volume 2. Blackwell, Oxford 1979, ISBN 0-903563-08-8 , pp. 284-287.

Translations

- Michèle Broze : La Princesse de Bakhtan. Essai d'analysis stylistique (= Monographies Reine Élisabeth. Vol. 6, ZDB -ID 187859-1 ). Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Bruxelles 1989, pp. 121–125.

- Frank Kammerzell : An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna to heal the demon-possessed Princess Bintrischji (Bentresch stele). In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament (TUAT). Volume 3: Wisdom Texts, Myths and Epics. Delivery 5: Myths and Epics III. Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn, Gütersloh 1995, ISBN 3-579-00082-9 , pp. 955-965, here pp. 960-964.

- Gustave Lefebvre : Romans et contes égyptiens de l'époque pharaonique. Adrien-Maisonneuve, Paris 1949, pp. 221-232.

- Miriam Lichtheim : Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume 3: The Late Period. University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1980, ISBN 0-520-03882-7 , pp. 90-94.

Overall and detailed studies

- Michèle Broze: La Princesse de Bakhtan. Essai d'analysis stylistique (= Monographies Reine Élisabeth. Vol. 6). Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Bruxelles 1989.

- Günter Burkard : Medicine and Politics: Ancient Egyptian healing art at the Persian royal court. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture (SAK). Vol. 21, 1994, ISSN 0340-2215 , pp. 35-57, especially pp. 47-55.

- Marc Coenen: A propos de la stèle de Bakhtan. In: Göttinger Miszellen (GM). No. 142, 1994, pp. 57-59.

- Didier Devauchelle: Notes sur la stèle de Bentresh. In: Revue d'Égyptologie (RdE). Vol. 37, 1986, ISSN 0035-1849 , pp. 149-150.

- Sergio Donadoni: Per la data della Stele di Bentres. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDAIK). Vol. 15, 1957, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 47-50.

- Hugo Greßmann : Old oriental texts and images for the Old Testament. Volume 1: Old oriental texts on the Old Testament. 2nd, completely redesigned and greatly increased edition. de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 1926, pp. 77-79.

- Frank Kammerzell : An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna to heal the demon-possessed Princess Bintrischji (Bentresch stele). In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament (TUAT). Volume 3: Wisdom Texts, Myths and Epics. Delivery 5: Myths and Epics III. Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn, Gütersloh 1995, ISBN 3-579-00082-9 , pp. 955-965.

- Scott N. Morschauser: Using History: Reflections on the Bentresh Stela. In: Studies for Ancient Egyptian Culture (SAK). Vol. 15, 1988, pp. 203-223.

- Georges Posener : A propos de la stèle de Bentresh. In: Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (BIFAO). Vol. 34, 1934, pp. 75-81, online (PDF; 693 KB) .

- Wilhelm Spiegelberg : On the dating of the Bentresch stele. In: Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes (RecTrav). Vol. 28, 1906, ZDB -ID 208133-7 , p. 181.

- Wolfhart Westendorf : Bentresch stele. In: Wolfgang Helck , Eberhard Otto (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Volume 1: A - Harvest. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1975, ISBN 3-447-01670-1 , Sp. 698-700.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, p. 955.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, p. 956, note g

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, p. 47.

- ↑ Posener: A propos de la stèle de Bentresh. 1934, pp. 75-81.

- ^ Spiegelberg: On the dating of the Bentresch stele. 1906, p. 181.

- ↑ Donadoni: Per la data della Stele di Bentres. 1957, pp. 47-50.

- ↑ Broze: La princesse de Bakhtan. 1989, p. 9.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, p. 960.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, p. 47.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, pp. 956 and 961.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, p. 963.

- ↑ Summary of translation and summary in: Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, pp. 960-964, pp. 955-956.

- ↑ a b Burkard: Medicine and Politics. Pp. 48–49, with reference to: Morschauser: Using History. 1988, pp. 203-223.

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, pp. 35-36.

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, pp. 36-37.

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, p. 50, with reference to: Morschauser: Using History. 1988, p. 217.

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, p. 50.

- ↑ Broze: La princesse de Bakhtan. 1989, pp. 79-84.

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, p. 50 and Broze: La princesse de Bakhtan. 1989, p. 74 and note 58.

- ↑ Broze: La princesse de Bakhtan. 1989, p. 84 (quote translated from French).

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, p. 51. with reference to Morschauser: Using History. 1988, p. 222.

- ^ Burkard: Medicine and Politics. 1994, p. 51.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, p. 958.

- ↑ Kammerzell: An Egyptian god travels to Bachatna. 1995, pp. 958-959.

- ^ Morschauser: Using History. 1988, p. 212, note 46, and Adolf Erman , Hermann Grapow : Dictionary of the Egyptian language. Volume 1. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1971, October 16.

- ^ Morschauser: Using History. 1988, p. 212, note 46, and Adolf Erman, Hermann Grapow: Dictionary of the Egyptian language. Volume 1. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1971, 15.20.

- ^ Westendorf: Bentresch stele. 1975, col. 700.

- ^ Morschauser: Using History. 1988, pp. 212-213 and note 47.

- ↑ Klaus Berger , Carsten Colpe (ed.): Religionsgeschichtliches Textbuch zum New Testament (= texts on the New Testament 1). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen et al. 1987, ISBN 3-525-51367-4 , p. 32.