C / 1881 K1 (Great Comet)

| C / 1881 K1 (Great Comet) [i] | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

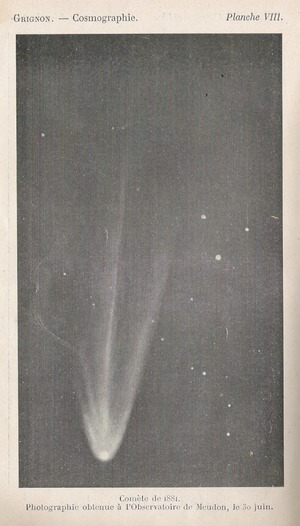

The comet on June 30, 1881

|

|

| Properties of the orbit ( animation ) | |

| Orbit type | long-period |

| Numerical eccentricity | 0.9961 |

| Perihelion | 0.7345 AU |

| Aphelion | 376 AU |

| Major semi-axis | 188 AU |

| Sidereal period | ~ 2586 a |

| Inclination of the orbit plane | 63.4 ° |

| Perihelion | June 16, 1881 |

| Orbital velocity in the perihelion | 49.1 km / s |

| history | |

| Explorer | John Tebbutt |

| Date of discovery | May 22, 1881 |

| Older name | 1881 III, 1881b |

| Source: Unless otherwise stated, the data comes from JPL Small-Body Database Browser . Please also note the note on comet articles . | |

C / 1881 K1 (Great Comet) (also called Comet Tebbutt ) was a comet that could be seen with the naked eye in 1881 . Due to its extraordinary brightness, some count it among the " great comets ".

Discovery and observation

The Australian astronomer John Tebbutt had already discovered the Great Comet C / 1861 J1 in 1861 . When, almost exactly 20 years later, on the evening of May 22, 1881, he habitually searched the western sky, with the stars of which he was very familiar, he found a foggy spot with the naked eye. When checked with a telescope, he could already see a broad tail . He immediately took positions and the next day informed the major observatories and an article in the Sydney Morning Herald to the public of his discovery.

At the time of its discovery, the comet was approaching its closest approaches to the sun and earth . It moved steadily in a northerly direction across the southern sky , but was initially only visible from the southern hemisphere until the end of May 1881 . On May 28, Benjamin Apthorp Gould observed an asymmetrical shape of the comet's nucleus in Argentina . The following day, the comet was observed from board a ship in the South Atlantic with a tail length of 6 ° and on May 30th, Chinese astronomers reported a “broom star” in the northeast. On May 31, observers in South Africa described a magnitude of 2 mag and a tail length of over 12 °. Even in the first week of June there were still numerous observations, including by Henry Chamberlain Russell at the Sydney Observatory , who recorded the changes in the comet's coma in detailed drawings. John Tebbutt also observed it until June 13th, before the comet, when viewed from Earth, approached the sun more and more and could no longer be observed.

On June 19, the comet passed the sun at a distance of only 7 °, which means that it almost pushed through the ecliptic between the sun and earth . Shortly afterwards it became an easily observable object for observers in the northern hemisphere . Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Peters observed him in Kiel on the evening of June 22nd with a brightness of 1 mag. In the following days there were numerous other observations by Friedrich August Theodor Winnecke in Strasbourg , Alphonse Louis Nicolas Borrelly in Marseille , and others in England, Germany, Scotland and Hungary.

Rays of different brightness emanating from the comet's nucleus have been described several times; an inner and an outer shell were also observed in the coma. The tail reached lengths of over 20 ° on June 25th, after which the observed length of the tail decreased again, on June 27th it was still 14 °.

The comet moved away from the sun and earth again at the beginning of July, but it could still be easily followed with the naked eye for the entire month. In the first week of July the brightness was still 2 mag. On July 16, the comet passed the North Star at a distance of just under 9 ° . By the end of August the tail was gone, but by mid-September the comet could still be seen with the naked eye for the entire night. By the end of October the brightness had dropped to 9 mag. The last observation of the comet was on February 15, 1882, when it was only faintly visible in a telescope.

The comet reached a brightness of 1 mag.

Effects on the zeitgeist

The comet attracted widespread attention after becoming visible to the northern hemisphere and observing it as a circumpolar object throughout the night from July to September 1881 .

Scientific evaluation

The 1881 comet appeared at a time when comet research was making great strides. The English photographer Usherwood and the American astronomer Bond from comet C / 1858 L1 (Donati) had taken the first photographic images of a comet a good 25 years earlier . These recordings on wet collodion plates only showed the lighter regions of the coma and parts of the tail. The photographs and the scientific achievements of the photographers had largely been forgotten.

It was not until the end of the 1870s that more sensitive, dry gelatine photo plates with silver bromide were available as a recording medium, and the bright comet of 1881 came at just the right time to give three astronomers the opportunity to take successful pictures.

Both the Englishman Andrew Ainslie Common and the American Henry Draper tried this on June 24, 1881 . The photographs showed the comet's head and parts of the tail. On July 1, the French Jules Janssen also managed to take a picture, but only a post-processed copy was preserved (see picture in the info box).

The comet of 1881 was not the first comet whose spectrum was observed, but its brightness enabled many researchers to take a major step forward in spectroscopic research on comets. Russell was able to observe the spectrum of the comet as early as June 6, when it was still in the southern sky. On June 24th, by Sir William Huggins and a little later by Henry Draper, spectrograms of the coma and the tail were obtained on photo plates for the first time. In the spectra of the entire tail, a continuum (scattered sunlight) and superimposed discrete "hydrocarbon" bands, which originate from the cometary gases, could be determined.

Building on the similar observations already made for comets C / 1858 L1 (Donati) and C / 1874 H1 (Coggia) , the observations of the constant changes in the coma and tail enabled astronomers of the time to have a better understanding of the structure and dynamics of the Comets.

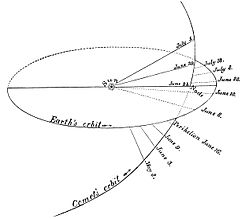

Orbit

The first orbital data for a parabolic orbit was determined by Benjamin Apthorp Gould at the end of May 1881 . Tebbutt also calculated orbital elements for the comet he discovered that were very similar to those of the Great Comet of 1807 , and a connection between these two comets was suspected. However, it was later proven that the two comets are completely different celestial bodies, but that they probably form a comet group with still others .

A relatively precise elliptical orbit could be determined for the comet from 98 observations over a period of 149 days , which is inclined by around 63 ° to the ecliptic . At the point of the orbit closest to the sun ( perihelion ), which the comet traversed on June 16, 1881, it was about 110 million km from the sun in the area of the orbit of Venus . The day before, on June 15, it had already reached the closest approach to Venus at 47.6 million km, while on June 20 it passed Earth in just 0.28 AU / 42.3 million km . This close proximity to the earth was also the reason for its observed brightness.

The comet moves in an extremely elongated elliptical orbit around the sun. According to the orbital elements , which are afflicted with a certain uncertainty, its orbit before its passage through the inner solar system in 1881 still had an eccentricity of around 0.9961 and a semi-major axis of around 190 AU, so that its orbit period was around 2650 years. Its last passage through the perihelion therefore took place around the year -770 (uncertainty ± 40 years). Due to the gravitational pull of the planets, however, its orbital eccentricity was reduced to around 0.9955 and its semi-major axis to around 165 AU, so that its orbital period was shortened to around 2110 years. When it reaches the point of its orbit furthest from the sun ( aphelion ) around the year 2930 , it will be about 49 billion km from the sun, over 328 times as far as the earth and almost 11 times as far as Neptune . Its orbit speed in the aphelion is only about 0.11 km / s. The next perihelion of the comet is expected to take place around the year 3990 (uncertainty ± 30 years).

The comet in literature

The British writer Thomas Hardy was inspired by the observation of the Great Comet of 1881 for his "astronomical novella" Two on a Tower .

See also

Web links

- C / 1881 K1 on www.kometarium.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c W. Orchiston: C / 1881 K1: A Forgotten "Great Comet" of the Nineteenth Century. In: Irish Astronomical Journal. Vol. 26 (1), 1999, pp. 33–44 ( bibcode : 1999IrAJ ... 26 ... 33O )

- ^ John E. Bortle: International Comet Quarterly - The Bright-Comet Chronicles. Retrieved June 29, 2015 .

- ^ GW Kronk: Cometography - A Catalog of Comets. Volume 2: 1800-1899. Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-58505-8 , pp. 472-483, 804-806.

- ^ P. Moore, R. Rees: Patrick Moore's Data Book of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2011, ISBN 978-0-521-89935-2 , p. 270.

- ↑ JM Pasachoff, RJM Olson, ML Hazen: The earliest comet photographs: Usherwood, Bond, and Donati 1858. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy. XXVII, 1996, pp. 129-145 ( bibcode : 1996JHA .... 27..129P ).

- ↑ RJM Olson, JM Pasachoff: Fire in the Sky: Comets and Meteors, the Decisive Centuries, in British Art and Science. Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-66359-8 , p. 254.

- ^ S. Hughes: Catchers of the Light: The Forgotten Lives of the Men and Women Who First Photographed the Heavens. ArtDeCiel Publishing, 2012, ISBN 978-1-62050-961-6 , p. 439.

- ↑ C / 1881 K1 (Great Comet) in the Small-Body Database of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (English).

- ↑ SOLEX 11.0 A. Vitagliano. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015 ; accessed on May 2, 2014 .

- ↑ SM Ahmad: Hardy and Comets. In: The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies. Vol. 2, No. 7, 2014, pp. 243-249. ( PDF; 74 kB ).