clown

A clown [ kla͜un ] is an artist whose primary art is to make people laugh . The term "clown" comes from an English term meaning "peasant booby" (16th century), used in English since about 1600 for "fool, jester"; German since the 18th century, perhaps under the influence of Shakespeare translations. An outdated term, especially used in dialects, is Pajass , Bajazzo (via French Paillasse from Italian Pagliaccio ).

term

The clown cannot always be distinguished from the comedian and the fool ; In any case, the term lacks the disrespectfulness of the jumping jack .

history

The figure of the clown develops from the zanni , the servant figures in the Commedia dell'arte , which in turn go back to similar figures in Greek and Roman comedy . From the beginning of the 16th century, clowns appeared during the breaks in English plays to entertain the audience. In the 16th century Arlecchino (later Harlequin , Hanswurst ), Pedrolino (later Pierrot ) and Pulcinella appeared in the Italian Commedia dell'arte. These figures, especially Pagliaccio , whose name became the Romanesque term for the modern clown, were further developed by Molière in the 17th century and by Goldoni in the middle of the 18th century . The corresponding German theater figure was called "Hanswurst" since the 16th century. The actor Franz Schuch approximated his Hanswurst again around 1750 to the Italian-French harlequin.

In the 17th century, the clown appeared as the mischievous opponent of Harlequin in the English Harlequinade , a genre inspired by the Commedia dell'arte. In Shakespeare's two plays, characters appear as clowns: in Othello (1603) a servant and in Winter's Tale (around 1610) a stupid shepherd.

Development of the circus clown

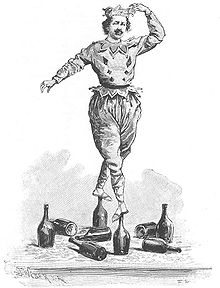

Modern clowns can be found in variety shows and especially in circuses. It all began in the second half of the 19th century in a game circle strewn with sawdust, which Philip Astley made the clown's scene. This was initially used for comical artistry on horseback (hence the circular shape). From this, the comedian with the horse developed in the following , for example in "scènes de manège" or "Two Englishmen on horseback". With the establishment of permanent venues ( Cirque Olympique , Cirque Medrano , Cirque d'hiver ), the performance of the clowns also changed. The clown mainly appeared as a pantomime, who stumbled around stupidly in the ring, fell and caught kicks and the like in interaction with other clowns. This already shows the similarity with our current circus clown, who shows a hodgepodge of bundled senselessness by wanting to step through doors with "danger" on them, looking curiously into gun barrels or sometimes eating candles out of hunger. With all these gestures the clown crosses the forbidden limits of society and thus becomes a mocker of reality. The circus with its clowns represents a scaled-down model of the entirety of a culture with all its irrationality and irony.

The modern clown

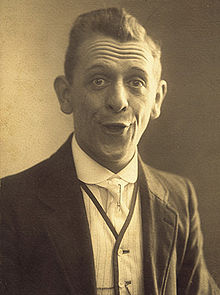

The first great forerunners of today's clowns were the pantomime artist Jean-Gaspard Deburau with his number “The Doctor” and Joseph Grimaldi , who developed the modern clown with the made-up face in London at the beginning of the 19th century, but which was not yet related with the circus but with the English pantomime.

In the Cirkus Renz, Tom Belling developed the typology of Stupid August , who initially caricatured what happened, but later appeared almost exclusively together with a white clown in the classic clown entree.

The nature and symbolism of the clown become particularly clear in the distinction between the figures, white clown and stupid August, who almost always appear together. In part, the figure of the announcer ( speaking stableman or ring master) is also included in this differentiation, whereby this and especially the director as superior can also serve as an object of fooling around.

Appearance

The disguise of the typical (circus) clown consists of different elements. He often wears too big, colorful clothes, a wig and a red nose. Often times, a strange inappropriateness is brought out by contrasting sizes such as oversized shoes and miniature instruments. The made-up face, which varies depending on the type, is also special.

- The costume: The costume characterizes the figure and the situation of the clown. With specially designed costumes, for example in terms of size, the figure and the game plot can be enlarged. In addition, certain costumes evoke certain associations, which is why acting contrary to expectations creates a discrepancy. This creates an effective way of creating the grotesque.

- The shoes: shoes can alienate the movement, which in turn can have interesting effects.

- The mask: The character can be enlarged with a mask. A distinction is made between full face masks and half masks. The full mask covers the entire face and mostly has hairpieces attached. By covering the face, facial expressions are lost, which is why excessive gestures are required with a full mask. The half mask leaves the mouth and lower jaw free, making it possible to speak. The mask also includes the red clown nose, which is an important point of reference as it defines the character. Make-up is especially important in pantomime in order to achieve a better perception of facial expressions. Color contrasts such as a white background, black-rimmed eyes and red mouth make this easier. By enlarging or reducing different parts of the face with make-up, the proportions of the face change, which in turn influences the facial expressions.

Other elements such as glasses, beards, hats etc. are used depending on the situation and intention.

Famous clowns

The Swiss clown Grock performed successfully in Europe, America and North Africa at the beginning of the 20th century. The Russian Oleg Popov became famous around the world in the 1960s. Andrei Nikolajew was one of the clowns of the Russian State Circus and was a professor at the Moscow Theater Academy. Charlie Rivels "Acrobat - schööön!" Is world famous . A clown of the film world was the British comedian and actor Charlie Chaplin .

Organizations

Clowns without limits

“Clowns without Borders” is - analogous to Médecins sans frontières ( Doctors Without Borders ) - an international organization of clowns who voluntarily travel to crisis areas to play for people and give workshops. A crisis area is understood to be an environment in which, for example, war, natural disasters or poverty prevail. The idea of "clowns without borders" comes from Spain, from where clowns have been traveling all over the world since 1993. Within a short time clowns from France and Sweden took over the idea and meanwhile (2015) twelve national organizations belong to it.

Clinic clowns

Clowns are finding their way more and more into hospitals and children's homes, where they work as clown doctors or " CliniClowns " (in Austria) by means of improvisation and mostly go from child to child to make them laugh. Examples are the “ Red Nose Clowndoctors ” in Austria, the “ Hôpiclowns ” and the Theodora Foundation in Switzerland or the “Dr Placebo” association in Bulgaria.

Coulrophobia

The pathological fear of clowns is known as coulrophobia. The University of Sheffield, England, asked 250 children between the ages of 4 and 16 about clowns. No one said they found clown pictures hanging on the walls in the hospital funny, some were afraid of them. A remarkable number of children felt uncomfortable at the sight of clowns.

Negative clown characters

The serial killer John Wayne Gacy appeared as "Pogo the Clown". An example of a negative clown character from literature is the character of Pennywise in Stephen King's novel It . The same applies to the character of Captain JT Spaulding in the horror film House of 1000 Corpses and the sequel The Devil's Rejects .

In the DC universe of DC Comics there is the villain character Joker , who appears as the antagonist of the hero Batman .

In the television series The Simpsons , Krusty the clown appears , a clown character with extremely dubious morals. Smoking, alcohol, pill abuse, sex and gambling are part of his lifestyle and repeatedly influence his show and the way it is perceived by the public. In addition, his merchandise items are often easily inflammable, toxic or sharp-edged. Krusty is often portrayed as a tragic figure drawn by life.

In the mid-2010s, the horror clown phenomenon emerged as a global trend that originally started in the United States. People dress up as horror clowns with the sole intention of scaring passers-by. So mostly intimidating grimaces or disfigured clown faces are depicted. With the help of utensils such as fake blood, weapons, chainsaws or tools, the horror effect should be increased.

See also

literature

- Constantin von Barloewen : Clown: On the phenomenology of stumbling. Athenaeum, Königstein 1981, ISBN 3-7610-8141-3 ; Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-548-34213-2 .

- Dieter Bartels : The clown theater 1-x-1. Ten big steps towards acting and comedy. Impuls-Theater-Verlag, Planegg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7660-9109-3 .

- Peter L. Berger : Redemptive laughter. The funny thing in the human experience. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998; 2nd edition 2014 (original title: Redeeming Laughte , translated by Joachim Kalka), ISBN 978-3-11-035903-9 .

- Roswitha von dem Borne: The clown: story of a figure. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-87838-969-8 .

- Jürgen Engel: Moving clown. Ways of theatrical intervention . In: Christian Hoffstadt u. a. (Ed.): What moves us? People in the field of tension between mobility and acceleration. Project, Bochum / Freiburg im Breisgau 2010, pp. 313–331, ISBN 978-3-89733-225-6 .

- Annette Fried, Joachim Keller: Fascination with the clown. Patmos, Düsseldorf 1996, ISBN 3-491-69067-6 .

- Johannes Galli : Clown: The desire to fail. Galli, Freiburg im Breisgau 1999, ISBN 3-926032-02-2 .

- Johannes Galli: Discover the clown in you: find serenity. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2000, ISBN 3-451-05058-7 .

- David Gilmore: The Clown in Us: Humor and the Power of Laughter. Kösel, Munich 2007 ISBN 978-3-466-30757-9 .

- Hanspeter Gschwend : Dimitri: The clown in me. Autobiography with another pen. Benteli, Bern 2003, ISBN 3-7165-1318-0 .

- Karl Hoche , Toni Meissner, Bartel F. Sinhuber: The great clowns. Athenaeum, Königstein im Taunus 1982, ISBN 3-7610-8237-1 .

- Birgit Holzer, Kerstin Hensel : The view through the clown clothes on the bones. Kerstin Hensel: "An Interview" in: Andrea Bartl (Ed.): Verbalträume, contributions to contemporary German literature, interviews with Friederike Mayröcker, Bastian Böttcher, Martin Walser, Tom Schulz and Kerstin Hensel, 2005, pp. 337–351, ISBN 978 -3-89639-477-4 .

- Gardi Hutter : The clowner. Panorama, Altstätten / Munich 1985, ISBN 3-907506-85-5 .

- Elodie Kalb: clowning. Communication between continuity and uncertainty. Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-8467-6247-9 .

- Fritz Karwath : I was a clown. Henschel, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-362-00371-0 .

- Michael Kramer: Pantomime and clowning: history of clowning from the Commedia dell'arte to the Festival of Fools; with instructions and suggestions for exercise and play . Burckhardthaus-Leatare-Verlag, Offenbach am Main 1986, ISBN 3-7664-9217-9 .

- Hans-Peter Krüger: Between laughing and crying. Volume I: The Spectrum of Human Phenomena. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-05-003414-9 .

- Hartmut Meesmann (Ed.): Discover the clown in you: Chances for a lively life. Publik-Forum Extra 2/2004, Publik-Forum-Verlagsgesellschaft, Oberursel, ISBN 3-88095-133-0 .

- Katharina Meiser, Sikander Singh (ed.): Fools, clowns, jesters. Studies on a social figure between the Middle Ages and the present , Wehrhahn Verlag, Hannover 2020, ISBN 9783865257543 .

- Oliver M. Meyer, Herbi Lips (Ed.): Grock - Stranger than the truth. Photo biography, ArtsEdition, Zurich 2006, ISBN 978-3-9522638-1-5 (special edition with DVD insert).

- Raymond Naef: Grock - the famous clown and his music , book and CD. edition accordion magazine 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-036319-1 .

- Tristan Rémy: clown numbers. Henschel, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-362-00259-5 .

- Natalia Rumjanzewa: clown and time. Henschel, Berlin 1989 (from the Russian by Hans-Joachim Grimm), ISBN 3-362-00369-9 (the study is based on the famous Soviet clowns Karandasch (MN Rumanzjew), Oleg Popow , Juri Nikulin and Leonid Jengibarow ).

- Cindy Sherman : clowns. Schirmer / Mosel , Munich 2004 in collaboration with Kestnergesellschaft Hannover, ISBN 3-8296-0168-9 .

- Georg Spillner : Clown NUK - The mask set me free, told and reported from 87 years of life, drawn and exposed. Arthur Göttert wrote the text after extensive tape discussions. Höttert, Löhne (Westphalia) 1995, ISBN 3-929793-29-6 .

- Mario Turra: The clown's laugh. Henschel, Berlin 1972, 1975, DNB 760069123 .

- Mario Turra (Ed.): Contemporary clown numbers. Henschel, Berlin 1977. DNB 770196322 .

Dissertations

- Andrea Pfandl-Waidgasser: Playful Seriousness: Clownish Interventions in Hospital Pastoral Care (= Practical Theology Today , Volume 113), Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-17-021725-6 (Dissertation Graz 2009, 301 pages, table of contents ; content text ) .

- Gisela Matthiae: Clown God: A Feminist Deconstruction of the Divine (= Practical Theology Today , Volume 45), Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne 1999, ISBN 978-3-17-016102-3 (dissertation University of Hamburg 1998, 320 pages).

- John Plant : Heyoka: the contraries and clowns of the Plains Indians. Publisher for American Studies , Wyk auf Föhr 1994, ISBN 3-89510-011-0 (Dissertation Freiburg im Breisgau) 1994, 240 page Hans-Ulrich Sanner: Tsukulawa: the Hopi clown ceremony as a mirror of their changing culture (4 microfiches ), 1992 DNB 931316596 (Dissertation University of Frankfurt am Main 1992, micro-reproduction of a manuscript).

- Annette M. Fried & Joachim Ph. Kelle Identity and Humor: A Study of the Clown 1991, ISBN 978-3-89228-722-3 (Dissertation University of Frankfurt am Main 1991, 637 pages, table of contents ).

- Götz Arnold: Representation and mode of action of the clownesque between "critical self-reflection" and "entertainment" using the example of FJ Bogner's clown theater "Sisyphos", Nold, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-922220-52-5 (dissertation FU Berlin 1990, 261 pages).

- Elizabeth Hale Winkler: The clown in modern Anglo-Irish drama (= European university publications , series 14: Anglo-Saxon language and literature , volume 50). Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Bern 1976, ISBN 978-3-261-02903-4 (Dissertation FU Berlin 1976, 297 pages).

The clown in literature

- Sebastian Brant : The Ship of Fools (1494)

- Erasmus of Rotterdam : In Praise of Folly (1511)

- Till Eulenspiegel (around 1510/1512)

- "Feste" / Fool in What you want by William Shakespeare (around 1601)

- Henry Miller : The smile at the foot of the ladder. 1948, German: Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-518-01198-7 .

- "Hans Schnier" in Views of a Clown by Heinrich Böll (1963)

- "Noman Noman" in Shalimar the Clown by Salman Rushdie (2005); German Shalimar the fool . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2006; Paperback, ibid. 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-23931-1

- "Pennywise", a clown as a scary monster in Es by Stephen King (1986)

- Edwin Ortmann : The clowns, love, death, radio play, Südwestrundfunk 2000.

- "Kasper Krone" in The Silent Girl by Peter Høeg (2006)

Web links

- Clown in Berufenet the Federal Employment Agency

- Gerhard Eberstaller: On the stage, in the ring, on the film screen - clowns in eternal struggle against the authorities. Of tragicomic rebellions . Wiener Zeitung , March 29, 2004, updated March 22, 2005; Retrieved February 7, 2012

Individual evidence

- ↑ Either from Latin colonus for "farmer" or from Old Norse klunni for "clumsy booby".

- ^ According to Pfeifer: Etymological Dictionary (1993): "[...] probably under the influence of Shakespeare translations". Eschenburg (1777, 4th or 9th volume) translates clown as "The Rüpel"; von Baudissin (1840) wrote "the fool."

- ↑ Ital. pagliacco, French paillasse, Spanish payaso, portuguese palhaço, catalan. pallasso, via French also German Paias ( around 1800 ). The French form was first documented in 1782 and was based on a folk etymology word for “straw sack” ( Le Trésor de la Langue Française Informatisé ); it was gradually superseded by Anglicism clown in the early 20th century .

- ↑ Cf. Barloewen, Konstantin von: Clown. On the phenomenology of stumbling. Frankfurt am Main: Ullstein non-fiction book, 1984.

- ↑ See Kramer Michael: Pantomime and clowning. History of clowning from the Commedia dell'Arte to the Festivals of Fools. Burckhardthaus-Leatare Verlag, Offenbach 1986.

- ↑ Clowns without limits

- ↑ Who we are . Clowns Without Borders International

- ↑ Study: Children hate clowns . ( Memento from January 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Tagesschau.de , January 17, 2008

- ↑ Kids frightened by hospital clowns . Sheffield Telegraph (English)