The Kraken

The Kraken , German Der Krake , is a poem by Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892). It first appeared in his poems, Chiefly Lyrical , in 1830 .

The work, which counts only 15 verses and is formally similar to a sonnet , has a sea monster on its subject, the legendary " octopus " of the North Sea , as evidenced by its title . The poet's peculiar choice of words and more or less explicit intertextual allusions to the Revelation of John and Percy Bysshe Shelley's verse drama Prometheus Unbound , however, point beyond this fairytale - folkloric (i.e. typically romantic ) subject and lead to diverse speculations about the religious or ideological ulterior motives of the Given the poet's occasion.

text

The following is the text of the poem in the final version (1872) and a translation into German (2000) provided by Werner von Koppenfels :

|

Below the thunders of the upper deep; |

Under the thunder of high sea

tide |

To slight in two changes of the text is identical to that of Erstabdrucks of 1830: the ancient writing , antient ' by replacing Tennyson , ancient' , the word , fins ' ( "fins") by , arms' ( "arms" at Koppenfels "Hands").

shape

The poem can be described as a sonnet out of joint ; it counts 15 instead of the 14 usual verses and follows an increasingly idiosyncratic rhyme scheme:

- [abab cddc efe aaf e]

The redundant final verse is particularly noticeable, especially since it is the only one that is not an iambic five-lifter , but a six-lifter, more precisely an alexandrine . But even if you disregard this unusual encore, the structure of the poem cannot be reconciled with the specifications of the Shakespeare sonnet or the Petrarch sonnet . The first two quartets, which are still halfway rule-compliant, suggest the first two quartets, while the following verses, composed in a terzine, are reminiscent of the Italian model, although the turning point or climax - here the transition from the description of the deep sea to end-time prophecy - is not yet as usual occurs after the eighth, but only after the tenth verse.

A more or less dissolute handling of formal requirements characterizes several of Tennyson's early works and in 1833 earned him a reproach from none other than Samuel Taylor Coleridge , who gave him an unsatisfactory grade in metrics and recommended that he stay on one, at most two, of the to limit classical lyric forms until he has at least mastered these. Behind Tennyson's supposed craftsmanship, however, one can certainly suspect intent, a cautious rebellion against the strictness of form that Coleridge demanded. In the poems, Chiefly Lyrical of 1830, there are some properly executed sonnets, but 50 years later Tennyson, now the most famous poet in the country, revealed what he actually thought of this form of poetry: “I hate the perfect sonnet with a perfect hatred ” (in German roughly:“ I hate the perfect sonnet with perfect hatred ”). At least in the case of The Kraken , the violations of the poetic convention can also be justified in terms of content and function, as the peculiarities are piling up in the lines that deal with the Apocalypse , i.e. the dawn of a new divine age, in which the Laws of verse to be rewritten.

In order to suggest a meaningfulness corresponding to the biblical theme of these last verses from the beginning, Tennyson uses a sentence figure with a particularly time-honored tradition: the first two verses, almost identical in meaning , represent a synonymous parallelism , as it is mainly from the poetic texts of Old Testament (and its translation in the King James Bible ) is known. They also establish a conspicuous syntactic pattern. Locations, i.e. adverbs or prepositional phrases ('From many a wondrous grot') , usually precede the statements and give the scene a static quality, just as if a painting were being described. The monotony of the underwater world underlines assonances such as see / flee / green / seen and light / height / lie / polypi , tautologies such as His […] sleep / The Kraken sleepeth , and most obviously the repetition of the first pair of rhymes deep / sleep in the Verses 12-13.

Sources, themes and motifs

Sailor's yarn

Despite its brevity, The Kraken is an extremely ambiguous work in which mythical, Christian and scientific motifs and terminology coexist. In the German translation, this fundamental ambivalence is already evident in the title, as "octopus" has two meanings in German today. The now dominant meaning of the word "eight-armed squid, octopus" has only been used since the work of the natural scientist Lorenz Oken (1779–1851); it is unknown in English. Here the word is only used in its original meaning, namely to designate a legendary sea monster that is supposed to be up to mischief in the North Sea .

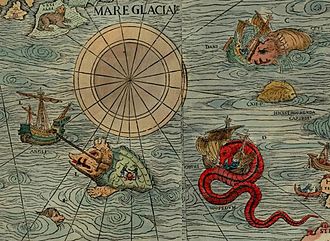

With Kraken mythical creatures is at Tennyson thus meant first exclusively. In a brief note to the poem in 1872, he referred to the description given by the Norwegian Bishop Erik Pontoppidan the Younger (1698–1764) of it. According to Pontoppidan, the octopus is more than a mile long, so that some captains have already mistaken it for an island and have fatally tried to anchor on it. If he dives, he causes huge ocean eddies, in which many a ship has sunk, others have been clasped by his huge arms and pulled into the depths. Tennyson was probably familiar with Pontoppidan's account from brief summaries in Biographie Universelle and the English Encyclopaedia . Other probable sources are the descriptions of the octopus in Thomas Crofton Crokers Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland (1825-1827) and in Walter Scott's novel The Pirate (1821). Isobel Armstrong also refers to the description of a sea serpent corresponding to the octopus in Olaus Magnus ' Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555), which Scott quotes in a footnote in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1803) and in which this sea monster, if not with the end of the world, so it is associated with a shaking of the worldly order, for its appearance heralds the nearness of “a wonderful walk in the kingdom; namely, that all princes die or be banished; or that terrible wars will rage. "

Like Scott, Croker and their German translator, the Brothers Grimm , Tennyson valued sailor's thread , fairy tales and other myths because of their aesthetic value as “folk poetry”, and like Scott he himself often took up popular myths in his art poetry; for example in the Poems, Chiefly Lyrical arrangements of the Arthurian legend ( The Lady of Shalott ) and of Sleeping Beauty (Sleeping Beauty) . Thematically, The Kraken in this volume is apparently closest to the fairytale poems The Sea-Fairies , The Merman and The Mermaid , which deal with mermen and mermaids . With these mythical creatures, which also live in an aquatic environment, Tennyson's sluggish and unconscious octopus ultimately has just as little in common with the sea monster described by Pontoppidan or Scott. The first lines, especially the words 'Far far beneath' , which remind you of the opening formula ' Once upon a time, in a land far, far away' (corresponds to German “ Once upon a time ... ”), set the tone for a fairy tale , but this expectation is ultimately not met.

science

In the further course of the poem, the language is increasingly interspersed with completely non-popular Graecisms and Latinisms ( 'abysmal' , 'millennial' ), and with the rather unpoetic word 'polypi', it now takes off into an explicitly scientific register . The "inhabitants" of the underwater world are anything but fairytale-like; in addition to polyps, only seaweed, sponges and worms can be observed here, but no otherworldly beings such as mermaids or the like. The restriction to natural phenomena is a logical consequence of the scientific worldview and the " disenchantment of the world ", but raises the question of what kind of creature Tennyson's octopus is, if not a sea monster. It is noticeable that the poem describes only the octopus' environment, but hardly its own shape; the few rays of sun that reach the depths do not illuminate it, but rather “flee” away from it ( faintest sunlights flee / About his shadowy sides ).

Not only in view of the naturalistic descriptions of the marine fauna around it, it makes sense to interpret the octopus as an ordinary animal, namely as an octopus. Since the 18th century, the theory has been widely discussed among natural scientists that the superstition of the octopus has a real core and that this supposed mythical creature could be giant cephalopods (like the giant squid first described in 1857 ), especially since sailors, especially whalers, time and again Alleged sightings or even attacks of such animals. Tennyson, in particular, may have known the two lengthy articles that zoologist James Wilson published in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine on the matter in 1818 . In this context, Tennyson's reference to the 'polypi' swarming around the octopus appears suggestive , since this name has only been used to refer to cnidarians such as sea anemones since the 18th century . In the case of ancient authors such as Aristotle and some zoologists until the 19th century, on the other hand, the cephalopods were subsumed under this name - possibly the "countless and immensely large" polyps with their "gigantic arms" do not denote zoophytes , but a large number of squids, therefore not a single “octopus”, but many. If one interprets polypi in the current sense of the word, however, a different explanation is available: in 1828 Humphry Davy speculated in his Salmonia , which Scott also sympathetically reviewed , that the sightings of sea monsters such as the octopus were due to the occasional mass occurrence of jellyfish or zooplankton; from a distance such swarms could appear like a single, gigantic organism.

Tennyson's fascination with zoophytes, molluscs and other "lower" forms of life was a result of his preoccupation with scientific works and in particular with theories of biological evolution , which radically questioned the traditional ideas of the divine creation and the role of man in it even before Charles Darwin . In England, this development was fueled in Tennyson's youth by the geological work of Charles Lyell and the discovery of Iguanodon bones in Sussex in 1822. His In Memoriam AHH (written between 1833 and 1849) is probably the most important discussion in English literature of the religious crisis that has been triggered, but an early work such as The Kraken can also be interpreted against this background; Tennyson's octopus is a creature from the distant past, it has been lying on the ocean floor for many aeons ('ages') , surrounded by sponges of millennial growth . According to an anecdote circulated by his son, Tennyson attracted attention when he was a student with comments on the theory of recapitulation and at the time speculated that the developmental stages of the human body could be traced back to the shapes of invertebrates. The octopus presents itself on the one hand as a form of life that is very far removed from human beings, but at the same time as its phylogenetic relatives, and thus invites biologistic considerations on the animal nature of human beings.

Apocalypse

In the final passage, the aquarium still life suddenly gives way to the portrayal of the end of the world, the “last fire”. In the choice of terms it becomes clear that this is not a mere earthly or phylogenetically significant cataclysm , but rather the progress of a divine salvation event, because in the last three lines there are some images from the end-time visions of the Revelation of John . In particular Rev 8,8-9 ELB can be plausibly connected :

“And the second angel trumpeted: And something like a great mountain of fire was thrown into the sea; and the third part of the sea turned to blood. And the third part of the creatures in the sea that had life died, and the third part of the ships was destroyed. "

as well as Rev 13: 1 ESV :

"And I saw an animal rise out of the sea with ten horns and seven heads, and ten tiaras on its horns, and names of blasphemy on its heads."

Richard Maxwell also refers to Rev 17: 8 ELB :

“The beast that you saw was and is not and will rise from the abyss and go into perdition; and the inhabitants of the earth, whose names are not written in the book of life from the foundation of the world, will be amazed when they see the beast that it was and is not and will be. "

Julia Courtney speculates that Tennyson put the end-time beliefs of his strict Calvinist aunt Mary Bourne in verse in these lines , but WD Paden interprets them against the background of the mythological typology of the Anglican theologian GS Faber (1773-1854), according to which all pagan myths of the world represent corrupted versions of the biblical word of God. Faber saw the typhon and the python of Greek mythology and the Midgard serpent of Germanic mythology as embodiments of the “ evil principle ” or the devil, comparable to the serpent in the Garden of Eden, sea monsters and sea serpents in particular as a pagan overmolded representation of the biblical flood .

Other interpretations suggest a political subtext, especially due to the seemingly innocuous line 'Battening upon huge seaworms in his sleep' , which is a reference to Percy Bysshe Shelley's verse drama Prometheus Unbound (1818, The unleashed Prometheus ), a mythical parable the renewing, but also the destructive power of political revolutions (in the historical context especially the French Revolution ). With Shelley, the rebellious “ Demogorgon ” conjures up the “ Genii ” from their dwellings scattered across the “ Oblivion ”, from the sky to the depths of the sea - 'to the dull weed some sea-worm battens on' , as Shelley writes - and pushes finally his father Jupiter from the throne. However, it is difficult to decide, in a political reading such as Isobel Armstrong in particular , whether the Kraken itself is to be understood as the embodiment of the once suppressed and now groundbreaking revolutionary impulse or, on the contrary, as the epitome of the old, sluggish, reactionary stasis, not in the end, since his appearance also means his death. Jane Stabler, on the other hand, points out that, unlike Shelley's “elemental spirits”, he just does not allow himself to be awakened from his twilight sleep and carried away into subversive activities, and interprets this as an expression of the poet's apolitical, even resigned worldview; The Kraken represents more of an escapist fantasy, a retreat from any political or social participation in a dim world of illusion.

Psychological interpretations

In a more general sense, Tennyson's octopus has also been interpreted in terms of depth psychology or psychoanalysis as a symbol of the unconscious or subconscious , in which suppressed or repressed urges accumulate until they finally discharge in a violent, perhaps fatal reaction. The Kraken is part of a series of poems in which Tennyson depicts a being that is hardly such, but rather an unconscious existence, for example in the case of the lotus eaters in The Lotos-Eaters who twilight in an apathetic intoxication . Tennyson's Sleeping Beauty , like the octopus, also sleeps a dreamless, death-like, but beautiful sleep:

She sleeps: her breathings are not heard

In palace chambers far apart.

The fragrant tresses are not stirr'd

That lie upon her charmed heart.

She sleeps: on either hand upswells

The gold-fringed pillow lightly prest:

She sleeps, nor dreams, but ever dwells

A perfect form in perfect rest.

There is also a certain thematic similarity to the beautiful Lady of Shalott , who is trapped in a tower on an island by a magic curse and dies as soon as she goes to Camelot on a boat and is seen by people; Loneliness, isolation and death characterize many other early poems such as The Dying Swan and Mariana - the famous saying by TS Eliot that Tennyson is the saddest of all English poets is famous .

reception

The Kraken is one of Tennyson's best-known and most frequently anthologized poems today . During his lifetime, however, in contrast to some other early works, he did not include it in the numerous volumes of poetry with which he became the most celebrated English poet of the Victorian era in the middle of the 19th century (from 1850 until his death in 1892 he was a poet Laureate official praises singer of the United Kingdom), only in 1872 he published it again in the first volume of a six-volume library edition of his works , entitled Juvenilia .

Nevertheless, The Kraken seems to have contributed to the popularization of the Kraken material early on, especially in the fantastic literature of the 19th century, even if a direct influence can only rarely be proven. A parody was written by Dante Gabriel Rossetti as early as 1853 , referring to Francis MacCracken, an early patron of the Pre-Raphaelites :

Getting his pictures, like his supper, cheap,

Far far away in Belfast by the sea,

His watchful one-eyed uninvaded sleep

Mac Cracken sleepeth. While the PRB

Must keep the shady side, he walks a swell

Through spungings of perennial growth & height:

And far away in Belfast out of sight,

By many an open do and secret sell,

Fresh daubers he makes shift to scarify

And fleece with pliant shears the slumbering green.

There he has lied, though aged, and will lie,

Fattening on ill got pictures in his sleep,

Till some Præ-Raphael prove for him too deep.

Then once by Hunt & Ruskin to be seen,

Insolvent he shall turn & in the Queen's Bench die.

Albert J. Frank suspects that Edgar Allan Poe knew the poem in 1832 from a review of the poems, Chiefly Lyrical, in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine , where it was printed in full, and his reading experience in his short story MS. Found in a Bottle (dt. The manuscript in the bottle was incorporated where it says at one point): "Soon it threw us into breathtaking heights up that not even erfliegt the albatross, soon we swam in the frantic fall into any water Hell where the air was suffocating and no sound disturbed the kraken's slumber. ”The attempts by Tennyson to interpret the mythical kraken scientifically were reflected in two of the most famous literary works of the 19th century, one of which was Herman Melville's Moby- Dick (1851) and especially in Jules Vernes Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (1869–1870, German "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea"); Tennyson's poem should have been known to both Melville and Verne. In the 59th chapter of Moby-Dick (The Squid) , the Pequod's crew sight a giant squid; that Melville, like Tennyson, also had the mythical, if not eschatological, qualities of the octopus in mind is testified by a letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne dated November 1851 , in which he whispers: Leviathan is not the biggest fish; - I have heard of Krakens.

In Verne's novel, Captain Nemo, the captain of the submarine Nautilus , which is also named after a cephalopod , and his involuntary guest, the French professor Aronnax, exchange ideas about such theories on several occasions and are finally attacked by a giant squid or octopus off the Lucay Islands . In the description of the kelp forests that preceded the attack, Richard Maxwell believes that he recognizes explicit borrowings from Tennyson's poem:

“Steep rocks loomed high under the sea, striving walls made of chipped stone blocks built in mighty layers, in between black, dark holes where our electric rays could not penetrate. These rocks were covered with thick bushes, gigantic laminariums and seaweed, a true trellis of aquatic plants, corresponding to a gigantic world. These colossal plants led us, Conseil, Ned and me, to talk about the giant animals of the sea. At around 11 a.m., Ned Land made me aware of a terrible swarm of seaweed in the great masses of kelp. "Well," I said, "there are the true polyps, and I wouldn't be surprised if we got to see some of these monsters."

A direct influence of Tennyson on William Butler Yeats ' The Second Coming has been alleged on various occasions , a poem that was written in 1919 under the impact of the First World War and in very similar images outlines a vision of the end of the world (here conceptually linked to the second resurrection of Christ ), whereby the apocalyptic "animal" here, awakened from its long sleep, does not perish, but is only "born".

Most likely is the assumption that Tennyson's poem a direct model for the "Cthulhu" myth is that fundamentally for several of the most famous horror stories of the American writer HP Lovecraft , in particular for the story Call of Cthulhu (1928, .: dt Call of Cthulhu ). According to this, Cthulhu is a creature who came to earth several hundred million years ago, armed with huge tentacles, who is trapped in a death-like sleep in the Pacific Ocean and, according to an obscure myth, will rise one day when the stars are right, world domination itself tear and eventually kill all life on earth; In the meantime he "calls" the same message from his prison in the depths out into the world: Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn , "In his house in R'lyeh the dead Cthulhu is dreaming waiting" . Similar to Lovecraft, Tennyson's octopus is reinterpreted in John Wyndham's novel The Kraken Wakes (1953, when the octopus awakens ) to be a gigantic extraterrestrial being who is up to the annihilation of mankind; Tennyson's poem is quoted here in full. Two years later, Jorge Luis Borges also reproduced The Kraken in its entirety in his Libro de los seres imaginarios (1957, Eng. "Unicorn, Sphinx and Salamander"), a kind of postmodern bestiary .

Benjamin Britten set The Kraken to music in his song cycle Nocturne op. 60 in 1958 for tenor , obbligato bassoon and strings.

literature

expenditure

The Kraken was first published in Tennyson's Poems, Chiefly Lyrical , Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange, London, 1830. The slightly revised version including the note on Pontoppidan appeared in 1872 in the first volume (Juvenilia) of the Library Edition of Tennyson's Works , 6 Volumes, Strahan & Co., London 1872–73. The modern standard edition of Tennyson's works is:

- Christopher Ricks (Ed.): The Poems of Tennyson . 2nd, improved edition. 3 volumes. Longman, Harlow 1987.

The Kraken can also be found in the one-volume selection edition with the full explanations of the three-volume edition:

- Christopher Ricks (Ed.): Tennyson: Selected Edition . 2nd, revised edition. Edited by Christopher Ricks. Pearson Longmen, Harlow and New York 2007.

Transfers into German

- The octopus . German by Ulla de Herrera, based on the Spanish translation by Jorge Luis Borges . In: Jorge Luis Borges: Unicorn, Sphinx and Salamander: A manual of fantastic zoology . Hanser, Munich 1964.

- The octopus . German by Werner von Koppenfels . In: Werner von Koppenfels, Manfred Pfister (Hrsg.): English and American poetry. Volume 2: From Dryden to Tennyson . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46458-0 , p. 392.

- The octopus . German by Joseph Felix Ernst. In: Joseph Felix Ernst, Philip Krömer (Ed.): Seitenstechen # 1 | Seafaring makes you better . homunculus publishing house, Erlangen 2015, ISBN 978-3-946120-00-1 , p. 185.

Secondary literature

- Isobel Armstrong: Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poets and Politics . Routledge, London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-203-19328-8 , pp. 50f.

- Julia Courtney: "The Kraken," Aunt Bourne, and the End of the World. In: The Tennyson Research Bulletin. 9, 2010, pp. 348-355.

- Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered Polypi. In: Victorian Poetry. 47, 1, 2009, pp. 7-23.

- James Donald Welch: Tennyson's Landscapes of Time and a Reading of "The Kraken". In: Victorian Poetry. 14, 3, 1976, pp. 197-204.

Web links

- "The Kraken" (1830) - Alfred Lord Tennyson on the Victorian Web , with annotations by Philip V. Allingham.

Individual evidence

- ^ Text according to Tennyson: Selected Edition . 2nd, revised edition. Edited by Christopher Ricks. Pearson Longmen, Harlow / New York 2007, pp. 17–18, and identical to the print in Tennyson's Juvenilia from 1872.

- ↑ Werner von Koppenfels, Manfred Pfister (Ed.): English and American poetry. Volume 2: From Dryden to Tennyson . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46458-0 , p. 392.

- ↑ Robert Pattison describes it as a "quasi-sonnet", in: Robert Pattison: Tennyson and Tradition . Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1979, p. 41.

- ^ Philip V. Allingham: Annotations to The Kraken in the Victorian Web

- ↑ Christopher Ricks: Annotations to The Kraken. In: Alfred Lord Tennyson: Selected Poetry . Penguin, London / New York 2008, p. 303.

- ^ Morton Luce: A Handbook to the Works of Alfred Lord Tennyson . G. Morton, London 1905, p. 82.

- ^ Henry Nelson Coleridge (Ed.): Specimens of the Table Talk of the Late Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Volume II, John Murray, London 1835, p. 164 f .: “The misfortune is, that he has begun to write verses without very well understanding what meter is. Even if you write in a known and approved meter, the odds are, if you are not a metrist yourself, that you will not write harmonious verses; but to deal in new meters without considering what meter means and requires, is preposterous. What I would, with many wishes for success, prescribe to Tennyson, –indeed without it he can never be a poet in act, –is to write for the next two or three years in none but one or two well-known and strictly defined meters, such as the heroic couplet, the octave stanza, or the octo-syllabic measure of the Allegro and Penseroso. "( GBS )

- ↑ Quoted in: Christopher Decker: Tennyson's Limitations. In: Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, Seamus Perry: Tennyson Among the Poets: Bicentenary Essays . Oxford University Press, New York 2009, p. 66.

- ^ Robert Pattison: Tennyson and Tradition . Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1979, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ James Donald Welch: Tennyson's Landscapes of Time and a Reading of "The Kraken". Pp. 201-202.

- ↑ Christopher Ricks: Tennyson. 2nd Edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1989, p. 41; Seamus Perry: Alfred Tennyson . Northcote, Horndon 2005, pp. 42-43.

- ^ Editor's note by Christopher Ricks in: Tennyson: Selected Edition . 2nd, revised edition. Pearson Longmen, Harlow / New York 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Isobel Armstrong: Victorian Poetry. Pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Walter Scott: Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh, 1802, Volume III, p. 320: 'They who in Works of Navigation, on the Coasts of Norway, employ themselves in fishing or Merchandise, do all agree in this strange story, that there is a Serpent there which is of a vast magnitude, namely 200 foot long, and more - over 20 feet thick; and is wont to live in Rocks and Caves toward the Sea-coast about Berge: which will go alone from his holes in a clear night, in Summer, and devour Calves, Lambs, and Hogs, or else he goes into the Sea to feed on Polypus, Locusts, and all sorts of Sea-Crabs. He hath commonly hair hanging from his neck a Cubit long, and sharp scales, and is black, and he hath flaming shining eyes. This Snake disquiets the Shippers, and he puts up his head on high like a pillar, and catcheth away men, and he devours them; and this hapneth not, but it signifies some wonderful change of the Kingdom near at hand; namely that the Princes shall die, or be banished; or some Tumultuous Wars shall presently follow. '

- ↑ Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered PolyPi. Pp. 10-11.

- ↑ My father - after perhaps reading Cuvier, or Humboldt - seems to have propounded in some college discussion the theory that "the development of the human body might possibly be traced from the radiated, vermicular, molluscous and vertebrate organisms." The question of surprise put to him on this proposition was, “Do you mean that the human brain is at first like a madrepore's, then like a worm's, etc.? but this cannot be, for they have no brain. " Hallam Tennyson: Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir . New York 1897, Volume I, p. 44; quoted in: Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered Polypi. P. 12.

- ↑ Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered PolyPi. Pp. 11-13.

- ^ Editor's note by Christopher Ricks in: Tennyson: Selected Edition . 2nd, revised edition. Pearson Longmen, Harlow / New York 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Julia Courtney: "The Kraken," Aunt Bourne, and the End of the World. In: The Tennyson Research Bulletin. 9, 2010, pp. 348-355.

- ^ WD Paden: Tennyson in Egypt: A Study of the Imagery in His Earlier Work . University of Kansas Press, Lawrence 1942, p. 149.

- ^ Isobel Armstrong: Victorian Poetry. Pp. 51-52.

-

↑ Shelley: Prometheus Unbound. 4th act, translation by Albrecht Graf Wickenburg . Rosner, Vienna 1876:

"DEMOGORGON

- Ye elemental Genii, who have homes

- From man's high mind even to the central stone

- Of sullen lead; from Heaven's star-fretted domes

- To the dull weed some sea-worm battens on:

A CONFUSED VOICE

- We hear: thy words waken Oblivion.

DEMOGORGON

- Spirits, whose homes are flesh; ye beasts and birds,

- Ye worms and fish; ye living leaves and buds;

- Lightning and wind; and ye untamable herds,

- Meteors and mists, which throng air's solitudes:

A VOICE

- Thy voice to us is wind among still woods.

DEMOGORGON

- Man, who worth once a despot and a slave,

- A dupe and a deceiver! a decay,

- A traveler from the cradle to the grave

- Through the dim night of this immortal day:

ALLES

- Speak: thy strong words may never pass away.

DEMOGORGON

- This is the day which down the void abysm

- At the Earth-born's spell yawns for Heaven's despotism, "

"DEMOGORGON

- You elemental spirits who live

- Everywhere - enthroned in the minds of people

- And lives in the dull lead - in the starry canopy

- And in the weeds from which the worm gets

- The lowly, be the food -

A CONFUSED VOICE.

- We hear! You can disturb oblivion from sleep!

DEMOGORGON.

- All you spirits who live in the flesh!

- All of you animals - bird, fish and worm,

- You buds and you leaves - lightning and storm,

- You untamed herds that float

- As meteors in the fields of heaven!

ONE VOTE.

- Your word is a breath of wind to us in silent forests!

DEMOGORGON.

- Human! Who was a slave and a despot

- Who was himself betrayed and offered deception!

ALL.

- Speak! May your word never pass away!

DEMOGORGON.

- This is the day when through man's power

- Heaven's tyranny swallowed the abyss! "

- ^ Isobel Armstrong: Victorian Poetry. P. 51f.

- ↑ Jane Stabler: Burke to Byron, Barbauld to Baillie, 1790-1830 . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke / New York 2002, pp. 218-220.

- ↑ So z. B. Robert Preyer: Tennyson as an Oracular Poet. In: Modern Philology. 55, 4, 1958, pp. 239-251, especially pp. 240-241; also Clyde de L. Ryals: Theme and Symbol in Tennyson's Poems to 1850 . University of Pennsylvania Press, 1964, p. 66 and Gerhard Joseph: Tennysonian Love: The Strange Diagonal . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 1969, pp. 36-37. For a more detailed psychoanalytic interpretation, see, for example, Matthew Charles Rowlinson, Tennyson's Fixations: Psychoanalysis and the Topics of the Early Poetry . University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville 1994, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Christopher Ricks: Tennyson. 2nd Edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1989, p. 41.

- ↑ TS Eliot: In Memoriam. In: Essays Ancient and Modern. Harcourt, Brace & Co., New York 1936, pp. 202-203.

- ↑ MacCracken (Parody on Tennyson's 'Kraken') in the Rossetti Archive , seen April 23, 2015.

- ↑ At times we gasped for breath at an elevation beyond the Albatross - at times became dizzy with the velocity of our descent into some watery hell, where the air grew stagnant, and no sound disturbed the slumbers of the Kraken. - MS. Found in a bottle . In: Thomas Ollive Mabbott (Ed.): The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe . Volume 2: Tales & Sketches I . Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass. 1978, pp. 131–146, here p. 139. German translation based on Edgar Allan Poe's works. Complete edition of the poems and stories , Volume 5: Fantastic journeys . Edited by Theodor Etzel. Propylaen-Verlag, Berlin [1922], pp. 11-26.

- ↑ Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered PolyPi. P. 16f.

- ^ Herman Melville: Correspondence . Edited by Lynn Horth. Northwestern University Press, Evanston 1993, p. 212.

- ↑ Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered PolyPi. P. 23; According to Verne's own statement, the following scene, i.e. the attack itself, is based on Victor Hugo's Les Travailleurs de la mer .

- ↑ Jules Verne: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea . Revised by Günter Jürgensmeier based on contemporary translations. pdf on the pages of the Arno Schmidt Reference Library, p. 437.

- ↑ z. B. Stephen George: Tennyson's The Kraken. In: The Explicator. 52, 1, 1993, pp. 25-27; Isobel Armstrong: Victorian Poetry. P. 480.

- ^ "The darkness drops again; but now I know / That twenty centuries of stony sleep / Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, / And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born? "

- ^ Philip A. Shreffler: The HP Lovecraft Companion . Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. 1977, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ For a comparison of The Kraken and Call of Cthulhu see Richard Maxwell: Unnumbered Polypi. Pp. 18-20.

- ↑ John Morton: Tennyson among the Novelists . Continuum, London / New York 2010, pp. 108-109.

- ^ Peter J. Hodgson: Benjamin Britten: A Guide to Research . Garland, New York 1996, p. 109.