The Karamazov brothers

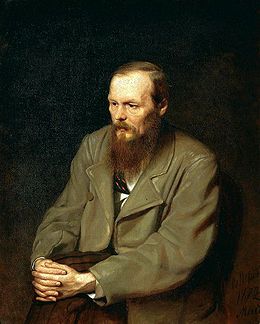

The Karamazov Brothers ( Russian: Братья Карамазовы Bratja Karamazovy ), in some editions also Karamazov , is the last novel by the Russian writer Fyodor M. Dostoyevsky , written between 1878–1880.

content

Dostoyevsky's novel has a structure similar to that of a criminal story : conflict situation in a family, murder, research and arrest of the suspect, court hearing with testimony, pleading and judgment. The reader follows these processes, finds out towards the end who the perpetrator is and witnesses the development of a miscarriage of justice . The importance of the novel, however, lies in the connection between these elements of tension with a representation of the social structure and the political-philosophical discussions in Russia at that time. The Karamazov family with children from various legal and illegal relationships, servants and love relationships with women who are socially differently valued is a reflection of this situation. The novel ends with a catastrophe for those involved: They are either physically or mentally ill or have to flee into exile or from Russia. Dostoyevsky's bearer of hope for a new moral society is Alexej, who is ultimately acclaimed by the young people.

main characters

The 55-year-old Patriarch Fyodor Karamazov comes from the old lower land nobility and got rich through speculative trading. He does not take care of his family and, after the untimely death of his two wives, initially leaves the upbringing of his sons to the servant Grigori Kutuzov and his wife Marfa or relatives, who provide high school education. He himself lives out his passions hedonistically .

The main plot, which is concentrated on a few days in September and, after a two-month jump, in November, begins with the return of the three grown sons. They represent different worldviews and discuss these with each other and with the father. For financial and personal reasons, especially between Fyodor and his eldest son, the relationship becomes increasingly tense.

Dmitri , the oldest (28 years old) is a soldier, leads an unrestrained life that is shaped by the "Karamazov soul", that is, emotionally contradicting, erratic behavior. An example of this is his complicated relationship with the proud officer's daughter Katerina (Katja) Verkhovtsev . Since he has fallen in love with her, but feels little heeded by her, he takes advantage of a financial bottleneck and suggests that she pay off her father's debts and thus save his father's honor if she becomes his lover. When she was forced to give in to overcoming her moral attitude, he, suddenly reflecting on the other side of his being, generously renounced her consideration. After he is in great financial need once again, but she has become rich through an inheritance, she offers him her money and marriage out of grateful love. They get engaged, but soon afterwards Dmitri falls in love with Agrafena Svetlova (Gruschenka) , who is not recognized in high society because of her past life with the Polish officer Musjalowitsch and the connection with her benefactor, the merchant Samsonov . She has an ambivalent passionate soul that corresponds to his character and is also courted by his father.

24-year-old Ivan , who attended university, makes a living from private lessons and writing philosophical articles. He embodies the enlightened, mind-oriented, atheistic intellectual . Out of disappointment about the suffering in the world that God has not prevented, he doubts the authority of the Christian commandments and the associated rewards and punishments. Therefore man is his own God and consequently is morally free in his decisions and deeds. This theory, in conjunction with his unhappy father relationship and the followers of Smerdyakov, leads to disaster. Another aspect of the complex family relationships is Ivan's love for Katerina, which his brother is willing to give to him. She is confused by this situation between jealousy of Grushenka and respect for the serious Ivan, which after his self-accusation of being morally responsible for the parricide leads to a change of her testimony in the course of the court process and to the burden of Dmitri.

Ivan's ideas are of particular interest to his presumed half-brother, Pavel Smerdyakov, who is the same age . This works in the house Karamazov as a cook and all the evidence, though Fyodor not committed as a father, suggest that he be illegitimate son with the deranged is Lizaveta Smerdjastschaja, the "Foul". He admires Ivan as his mentor and, believing in his consent, is ready to commit murder for him in order to give him a greater inheritance. He hopes that this will be recognized. However, when the latter is appalled by his deed and his own unconscious desires, he hangs himself without leaving a confession, allowing Dmitri to be convicted.

Alexej ("Aljoscha") is the youngest son (20 years old) and Ivan's full brother. He is declared the protagonist by the narrator in the foreword and accompanies the reader most of the time. He is a novice and student of the priest monk and Starez Sossima , who is portrayed as a counter-figure to Fyodor and Alexei's spiritual father. Like his role model Sossima, Alexej represents a Russian Orthodox Christianity centered on compassion, mutual forgiveness and the forgiveness of guilt. He tries to mediate in the complicated personal relationships and is constantly on the way from one person to another, to listen to the different stories, to pass on messages and to gain understanding for one another. In this way he succeeds in reconciling nine-year-old Ilyusha Snegirev , who is despised because his father has been dismissed from his job , with his schoolmates, including Kolja Krassotkin, whom he admires. Alexej also first of all addresses the marriage wishes of the mentally and physically ill, 14-year-old Lisa Chochlakow , who is in love with him , but skilfully shifts these wishes into the future and thus helps her to cope with her crisis. With this attitude he leaves the monastery after Sossima's advice.

action

The main storyline begins with Dmitri's argument with his father, who allegedly owes him money from his mother's inheritance and who is courting the same woman, Agrafena Alexandrovna. On the first two days (1st and 2nd part) this conflict situation unfolds increasingly and escalates on the third (3rd part): Iwan drives to Moscow, disappointed that Katerina cannot break away from him despite Dmitri's turning away All the while, Dmitri tries to borrow money to live with Gruschenka, watches the father's house to see if she visits his father, and knocks down the servant Grigori, who surprised him in the garden. Finally, he learns of Gruschenka's meeting with her former lover, the Polish officer, in Mokroje and travels after her. In the meantime, Smerdyakov has taken advantage of the situation, murdered Fyodor, laid traces and hid the 3,000 rubles.

In the trial before the district court (4th part) Dmitri is accused of planned murder and theft. Since he has stated on various occasions that he wanted to kill his father and also assaulted him physically, the suspicion fell on him immediately, especially since he was at the scene (3rd part, 8th book, 4th chapter) and on the same night for An orgiastic festival with Gruschenka in an inn in the village of Mokroje raised a lot of money (Part 3, Book 8, Chapter 5 and 6), although he had previously tried in vain to borrow large sums from his friends. The prosecutor suspects that after the murder, he stole the 3,000 rubles his father kept to give to his beloved when she visits him. There are no witnesses, but the evidence speaks against him and the court does not believe his confused declaration, confirmed by Katerina, that the money belongs to her, and so Dmitri is eventually sentenced to forced labor in Siberia . Initially, he accepted this as a just punishment for his hatred and thoughts of murder, but then agreed to his brother Ivan's escape plans. He and his brother Alexej become aware that the punishment, especially since he is innocent, would be too heavy for him and that it would perish him. The real perpetrator is Smerdyakov, who confesses to Ivan the murder (Part 4, Book 11, Chapter 8) and hanged himself the day before the trial began. He believed that by doing this he was complying with an unspoken request from Ivan.

Further stories illustrating the topic of the parent-child relationship are interwoven with this main thread of the plot. For example, that of the landowner Katerina Chochlakow and her over-sensitive, 14-year-old daughter Lisa, who has been paralyzed for six months and is in love with Alexej. While Ms. Chochlakow plays a connecting role in the novel because of her close communicative network, the plot about Starzen Sossima (Part 2, Book 6, Chapter 2), a highly respected monk from a monastery near the city, in which Aljoscha forms one Has lived for a long time, has its own focus: an alternative world to the secularized city. Like Sossima, the impoverished former soldier Nicolai Snegirjow also functions as a loving and fatherly contrasting figure to Fyodor Karamazov: his son Ilyusha, who is ill with consumption, cannot get over the ridicule of his father by Dmitri and dies at the end of the novel.

idea

The Karamazov brothers are strongly constructed as a “novel of an idea”: three brothers who stand for different principles (Ivan for thinking, Dmitri for passion, Aljoscha for creative will) and who each have a female figure at their side stand two Father figures opposite: their biological father, who symbolizes procreation and death, and the starzen Sossima as the embodiment of sacrifice and resurrection. Because of their hatred of old Karamazov, the brothers are entangled in guilt and live in turmoil (Russian: nadryw ). In Ivan's reflections, the author reflects his criticism of the philosophical and ethical uncertainty in Russian society. Iwan stands for the intellectual, western-minded doubter of God and all values, who is sick, so to speak, from the Enlightenment , but at the same time is deeply moved by human love. His doubts drive him insane: He is not sure whether a little devil appearing in his room is an independent transcendent phenomenon or his own projection (4th part, 11th book, 9th part). In addition, through the three conversations with Smerdyakov, he has to recognize that he gave him the cause of the murder and that in reality he was its master. But nobody wants to believe him in court because he speaks in a kind of delusional state. Rather, his statement is only interpreted by the prosecution as an expression of his generosity, since he is accused of lying in order to exonerate his brother.

The sons can only be freed from their entanglement by accepting their guilt and the atonement imposed for it (even if they are innocent in the legal sense) and instead of revolving around themselves in an egotistical and egocentric manner, devoting their lives to "working love" . The motto of the novel also points to this meaning of life through atonement, sacrifice and charity : “Truly, truly, I say to you: If the grain of wheat does not fall into the earth and perish, it remains alone; but when it dies, it bears much fruit ”( Jn 12:24 NIV ).

The novel unfolds a wealth of deep thoughts about the Christian religion and the basic human questions of guilt and atonement , suffering and compassion , love and reconciliation . Dostoevsky conveys a specific belief in God through the figure of Starzen.

In Ivan's legend of the Grand Inquisitor (Part 2, Book 5, Chapter 5), which he tells Aljoscha as an expression of his deepest convictions, Dostoevsky formulates the theodicy problem, as well as Fjodor's question to his two sons : "Is God dead?" Fyodor only knows the doubt. Ivan cannot and does not want to accept a God who allows innocent suffering: “I do not deny that there is a God, but I reject this world created by him. I'll give him back my entry ticket to this world. ”(Part 2, Book 5, Chapter 4). Accordingly, in his legend, the Grand Inquisitor takes over power on earth and rules with a strict system of penalties to regulate people's lives. He sends Jesus, who appeared in the world, back into transcendence. Aljoscha, on the other hand, refers to God's compassionate act in Christ .

Narrative form

An anonymous narrator or author (preface), who describes himself as a resident of “our city”, gives an overview of the family history of Karamazov (Part 1, Book 1) and the biographies and ideas of others , in a kind of authorial manner People. On the other hand, the actions and the narrations integrated into them are usually presented chronologically and, in personal form , from the perspective of the sons, predominantly from that of Alexej. The author maintains the tension by omitting the execution of the murder and turning it on as a review before the trial begins. This also enables the reader to check the chains of evidence of the prosecutor and the defense attorney.

Due to the differing positions, the many conversations and the different evaluations represented in them, e.g. B. of the Karamazov sons and their discussion partners as well as the detailed analyzes during the court hearing and pleadings, a polyphonic , polyperspective picture emerges that Mikhail Bakhtin described as typical of Dostoyevsky's novels.

Influences

After the death of his youngest son Alexei in May 1878, Dostoyevsky sought help from Starez Amwrosi in the Optina monastery near Koselsk in June of the same year . The author worked this experience into the design of Starez Sossima as well as into the story of Snegirev and the nine-year-old Ilyusha, whose death and burial are described towards the end of the novel. In this context, in contrast to this affectionate father-son relationship, the naming "Fyodor" for the father Karamazov and "Alexej (Aljoscha)" for his idealized youngest son, the hope of the novel, is important for the interpretation.

Chapter 5 of the first book is based heavily on Kliment Zedergolm's hagiography of Starez Leonid , which was written a few years earlier in the presentation of the starcy . Dostoyevsky received further inspiration from his friendship with the religious philosopher Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov and from the philosophical writings of Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov .

reception

The reception of the work was of exceptional intensity, both negatively and positively. The Russian philosophers Wladimir Sergejewitsch Solowjow , Wassili Wassiljewitsch Rosanow and Nikolai Alexandrowitsch Berdjajew as well as the writer Dmitri Sergejewitsch Mereschkowski made respectful reference to the religious ideas developed by Dostoyewski. Dostoevsky and in particular the Karamazov brothers Henry James , DH Lawrence , Vladimir Nabokov and Milan Kundera viewed them very critically , who criticized the morbid and depressive mood of the novel, among other things. Nabokov emphasized the lack of external realism : Unlike Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky does not characterize his people through details in clothing, apartment or surroundings, but through their psychological reactions and ethical situations, as is common in plays :

“The novel The Brothers Karamazov always gave me the impression of a sprawling play, with just as much furniture and equipment as the various actors needed: a table with a damp, round place where there was a glass, a yellow painted window with it it should look as if the sun was shining outside, or some bushes that a stage worker quickly got hold of and put somewhere. "

Sigmund Freud described The Karamazov Brothers as one of the most powerful novels in world literature. In the essay Dostoevsky and the killing of the father from 1928 he analyzed the work psychoanalytically and worked out its oedipal themes .

In 1920, Hermann Hesse saw the Karamazov brothers not as a linguistic work of art, but as a prophecy of the "fall of Europe" that seemed to be imminent. Instead of the value-bound ethics of Europe, Dostoevsky preached "an ancient Asian- occult ideal, [...] an understanding of everything, allowing everything to apply, a new, dangerous, gruesome holiness," which Hesse associated with the October Revolution :

"Half of Eastern Europe is already on the way to chaos, drunk in holy madness along the abyss, and sings to it, sings drunk and hymnically like Dmitri Karamasoff sang."

Some interpreters see in the figure of the Grand Inquisitor, in particular, an embodiment of the mania for domination and totalitarianism , a model of the coming dictatorship of atheistic socialism, of which Ivan is the mastermind. Regarding the importance of the legend, Dostoevsky himself wrote in 1879: “If belief in Christ is falsified and mixed up with the aims of this world, then the meaning of Christianity is also lost. The mind falls into disbelief, and instead of the great ideal of Christ, only a new tower of Babel will be built. While Christianity has a high conception of the individual human being, humanity is only viewed as a large mass. Under the guise of social love, nothing but overt misanthropy will flourish. "

For the French existentialist Albert Camus , nobody was able to “give the absurd world such haunting and agonizing stimuli ” in the same way as Dostoevsky .

The translator Swetlana Geier judges that Brat'ja Karamazovy shows "in sublime form" features of Dostoyevsky's inner biography. He thus “corrected and perfected” thoughts from his earlier novels, in which he followed through to the last resort what happens to a person without God.

The literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki described the novel as the best novel in the world:

“When I read this book then, neglecting my homework and my friends, I thought it was the best novel in the world. Between us: I still believe it. "

Translations into German

- unknown translator: The Karamazov brothers. Grunow, Leipzig 1884.

- EK Rahsin : The Karamasoff brothers. Piper, Munich 1906, ISBN 3-492-04000-3

- Karl Nötzel : The Karamasoff Brothers. Insel, Leipzig 1919.

- Friedrich Scharfenberg: The Karamasoff Brothers. J. C. C. Bruns' Verlag, Minden 1922

- Johannes Gerber: The Karamazov brothers. Hesse and Becker, Leipzig 1923.

- Hermann Röhl : The Karamazov brothers. Reclam jun., Leipzig 1924; again, ISBN 3-458-32674-X .

- Bodo von Loßberg: The Karamazov brothers. Th. Knaur Nachf., Berlin 1928.

- Reinhold von Walter: The Karamazov brothers. Gutenberg Book Guild , Berlin 1930

- Valeria Lesowsky: The Karamazov Brothers. Gutenberg-Verlag, Vienna 1930.

- Hans Ruoff : The Karamazov brothers. Winkler, Munich 1958.

- Werner Creutziger: The Karamazov brothers. Structure, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-351-02311-1 .

- Svetlana Geier : The Karamazov brothers. Ammann, Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-250-10259-8 , ISBN 3-250-10260-1 .

literature

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky, W. Komarowitsch: The original figure of the Karamasoff brothers, Dostojewskis sources, drafts and fragments . Ed .: René Fülöp-Miller, Friedrich Eckstein. R. Piper & Co., Munich 1928 (explained by W. Komarowitsch with an introductory study by Sigm. Freud).

- Alexander L. Wolynski: The empire of the Karamazoff . R. Piper & Co., Munich 1920.

- Horst-Jürgen Gerigk (Ed.): The Karamazov Brothers - Dostoyevsky's last novel in today's perspective, eleven lectures . Dresden University Press, 1997, ISBN 3-931828-46-8 .

- Hermann Hesse : The Brothers Karamazov or The Downfall of Europe. In: New Rundschau . (1920 online at archive.org) or a more recent print in: Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse. The world in book III. Reviews and essays from 1917–1925 . Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-518-41341-4 , pp. 125-140 .

- Peter Dettmering: Essay on Karamazov ( online on Google books)

- Sigmund Freud : Dostoevsky and the killing of the father. Freud study edition. Volume 10, Frankfurt am Main 1969f., ( Online on text log )

- Martin Steinbeck: The problem of guilt in the novel "The Karamazov Brothers" by FM Dostojewskij. RG Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-89406-831-0 .

- Robin Feuer Miller: The Brothers Karamazov: Worlds of the Novel . Yale University Press, New Haven 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-15172-5 .

Adaptations

Film adaptations

- 1915 - The Karamasoff Brothers (1915)

- 1920 - The Karamasoff Brothers - Director: Carl Froelich

- 1930/1931 - The murderer Dimitri Karamasoff - Director: Fjodor Ozep

- 1958 - The Brothers Karamazov ( The Brothers Karamazov ) - Director: Richard Brooks

- 1969 - The Karamazov Brothers ( Bratja Karamasowy ) - Director: Ivan Pyrjew , after his death: Kirill Lavrov and Michail Ulyanov

- 1991 - The Grand Inquisitor - Director: Beat Kuert , based on a legend within the novel

- 2008 - The Karamazows - Director: Petr Zelenka

- 2009 - The Brothers Karamazov , Russian television multi-parter - Director: Yuri Moros

- 2010 - Karadağlar - Director: Ertunç Şenkay

Opera

- 1922–1927 - The Karamazov brothers (music: Otakar Jeremiáš )

theatre

- 1910 - Братья Карамазовы (Bratja Karamasowy) , drama, staging at the Chekhov Art Theater in Moscow , co-director: Vladimir Nemirowitsch-Danchenko

- 2014 - Karamasow , drama by Thorsten Lensing

- 2015 - The Karamazov brothers based on Fyodor M. Dostojewskij - Castorf, Volksbühne Berlin

Web links

- The Karamazov brothers in the online full text at Gutenberg-DE (translation by Hermann Röhl)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Svetlana Geier : Brat'ja Karamazovy. In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon im dtv . Volume 3, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 1616.

- ↑ Svetlana Geier: Brat'ja Karamazovy. In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon im dtv. Volume 3, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 1616.

- ↑ Mikhail Bakhtin: Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics . Ullstein 1988.

- ↑ Dirk Uffelmann: The humiliated Christ. Metaphors and Metonymies in Russian Culture and Literature. Böhlau, Vienna 2010, p. 514.

- ↑ Leonard J. Stanton: Zedergol'm's Life of Elder Leonid of Optina As a source of Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. In: Russian Review. 49, 4 (October 1990), pp. 443-455.

- ↑ Svetlana Geier: Brat'ja Karamazovy. In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon im dtv. Volume 3, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 1616.

- ^ Robin Feuer Miller: The Brothers Karamazov: Worlds of the Novel . Yale University Press, New Haven 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-15172-5 , pp. 7, 8 .

- ↑ “The novel The Brothers Karamazov has always seemed to me a straggling play, with just that amount of furniture and other implements needed for the various actors: a round table with the wet, round trace of a glass, a window painted yellow to make it look as if there were sunlight outside, or a shrub hastily brought in and plumped down by a stagehand. "Vladimir Nabokov: Lectures on Russian Literature. Edited by Fredson Bowers. New York 1981, p. 71.

- ^ Josef Rattner , Gerhard Danzer: Psychoanalysis today: for the 150th birthday of Sigmund Freud . Königshausen & Neumann , Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3386-8 , p. 42 .

- ↑ Hermann Hesse: The Karamasoff Brothers or the Fall of Europe. Ideas while reading Dostoevsky. In: New Rundschau . 1920, pp. 376-388 ( online , accessed November 16, 2013).

- ↑ Geir Kjetsaa: Dostojewskij: convict - player - poet prince. Gernsbach 1986, p. 411.

- ↑ Quoted from Swetlana Geier: Brat'ja Karamazovy. In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon im dtv. Volume 3, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 1616.

- ↑ Svetlana Geier: Brat'ja Karamazovy. In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon im dtv. Volume 3, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 1616.

- ↑ Highest Quality from Russia - Who's the Greatest Novelist. Accessed November 11, 2016

- ↑ Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft WBG, Darmstadt 1964, without ISBN, thin print edition; Afterword of Übers, pp. 1277–1286; Notes (explanations of terms) pp. 1287–1295.

- ↑ The Karamazov Brothers (Russia 1915) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ The Brothers Karamazov (USA 1958) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ The Brothers Karamazov (Soviet Union in 1969) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Karamazov (Czech Republic 2008) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ The Brothers Karamazov (Russia 2009) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Karadağlar showtvnet.com ( Memento from March 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (Turkey 2010)

- ↑ Братья Карамазовы (Drama) on the website of the Chekhov Art Theater Moscow (Russian), accessed on July 10, 2020