Ghaznavids

|

|||||

| Capital |

Ghazni

(977–1163) (1163–1186) |

||||

| Form of government | monarchy | ||||

| religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| language | Persian | ||||

| founding | 977 | ||||

| resolution | 1186 | ||||

The Ghaznavids or Ġaznaviden ( Persian غزنویان- Ġaznavīyān , Ghaznawian ; Arabic الغزنويون- al-Ġaznawīyūn ) were a Turkish-born , Muslim dynasty founded by former military slaves of the Samanids . It ruled from 977 to 1186 in the eastern Iranian countries , with its sphere of influence at times extending in the west to Jibal and in the east to the Oxus and northwestern India . The city of Ghazni in Khorasan , today Ghazni in Afghanistan , has long been the center of their empire.

Origin and meaning

The Ghaznavids were originally Turkish , but origin in all respects to the region Khorasan assimilated (in present-day Afghanistan), which is why many historians also described as "iranisierte" or "persifizierte" Turks. They are descended from Karluk slaves who, especially after the Samanids' victory over the Karluk Turks in 893, converted to Islam in large numbers and from then on were in their service as military and court slaves ( ghulām ). The name of the dynasty is derived from the name of the city of Ghazna. In historical sources they are called "Āl-e Sabuktekīn" ( Persian آل سبكتكين) or "Banū Sabuktekīn" ( Arabic بنو سبكتكين) designated.

The rule of the strictly Sunni Ghaznavids had in many ways the character of a continuation of the Samanid rule, because the Ghaznavids inherited the administrative, political and cultural traditions of their predecessors and thus laid the foundations for a Persian state in northern India. As a result, despite the short period of time, they had a far-reaching influence on the culture and history of the areas they ruled.

history

Establishment of a dynasty

The foundation stone for the establishment of the empire was laid in 962 by the Turkish general Alp-Tigin in the region around Ghazna . Alp-Tigin was a former slave in the service of the Samanids, who in the question of succession to the throne against the Emir Manṣūr b. Nūḥ (961–976) had intrigued and therefore appropriated Ghazna beyond the Hindu Kush Mountains in order to escape revenge. He was able to occupy the city in 962 and died the following year. He was followed by other slave officers, first his son Isḥāq (963–966), who recognized the supremacy of the Samanids and called for their help against his rival Lawik. The region surrounding this city subsequently remained in the hands of Turkish rulers.

Finally, Alp Tigin's former slave and later son-in-law, Sebük Tigin (977-997), succeeded in founding a dynasty that could rule until 1186, although he too initially officially ruled in the name of the Samanids. Evidence of Sebük Tigin's recognition of the supremacy of the Samanids is provided by the mintings on his coins. He helped the Samanids against the Simjurids in 992 and 995. Sebük Tigin first went into a "holy" war against the Hindushāhīs , whose king Djaypal (965-1001) he defeated in 979 and 988. With this, Sebük Tigin had also conquered the fortresses on the Indian border. Sebük Tigin took Djaypal prisoner, but released him after paying tribute. With the decline of the Samanid Empire in Transoxania , he succeeded in appropriating further areas in 994, which he and his son Mahmud, after helping Manṣūr b. Nūḥ were subordinated. The emir had been threatened by a revolt by his generals. The empire now also included Balochistan , Ghor , Zabulistan and Bactria . In this way, Sebük Tigin - an exceptionally powerful and ambitious ruler and a staunch Sunni - laid the foundation for one of the longest-lived empires in the region. His son then built on this foundation and brought the kingdom to its climax. The Samanid Empire finally perished between 999 and 1005 when the Qarakhanids occupied the Samanid capital Bukhara and came to an understanding with the Lord of Ghazna.

Peak of power under Mahmud of Ghazni

Under Sebük Tigin's son Maḥmūd Yāmīn ad-Daula (called Mahmud of Ghazni) (ruled 998-1030) the dynasty already reached its climax.

The legitimation of his rule in Khorāsān was awarded to Mahmud by the Abbasid caliph al-Qādir bi-'llāh . Sebük Tigin had actually chosen his other son Ismail as his successor, but Mahmud cleverly ousted him. From 999 Mahmud had secured his position as his successor. Mahmud of Ghazni is considered to be the most important ruler in the history of the Ghaznavids. Culturally he leaned strongly towards (ancient) Iran and was receptive to the emerging new Persian literature . So he hired Abū l-Qāsim-e Firdausī as his court poet. Through uninterrupted fighting, Mahmud gradually built a great military empire that was under his personal control. His victorious battles and his reputation as a successful military leader were a guarantee that volunteer fighters ( ghozāt or moṭaweʾūn ) from all over the east of the Islamic world were always found for his army. This professional Ghaznavid army was made up of the most diverse peoples of the Ghaznavid Empire, including Arabs and Dailamites . The essential core of the army, however, always formed Turkish slaves ( ghulāmān-e chāṣ ), who made up the elite of the Ghaznawid army and the personal bodyguard of the ruler. On this military base, the court and administration of the empire were organized on the model of the Samanids.

As one of the most important Muslim conquerors, Mahmud of Ghazni, after reaching an understanding with the Qarakhanids, began campaigns on the Indian subcontinent from 1001 and advanced to Gujarat , Kannauj and central India. Even if he did not aim to conquer India beyond the Indus region and the Punjab , he weakened the Hindu states considerably through his usually successful raids and thus prepared the later conquest of India by the Ghurids . By conquering the Punjab, Mahmud had created extensive territory in India for Islam and thus laid the foundation for the division of this region according to religions. The establishment of the independent state of Pakistan in 1947 goes back to this religious division of the region by Mahmud.

Mahmud, who like his father was a staunch Sunni, replaced his father's ties to the Samanids with loyalty to the Abbasid caliph al-Qādir bi-'llāh. This loyalty, however, only remained nominal, since at that time Baghdad , the capital of the Abbasids, could not exert any influence on the far east and the Sunni Abbasids themselves were in turn dominated by the Shiite Buyids . The Iranian Buyids had now reached the height of their power and were attacked several times by Mahmud, who also served his caliph. At the time of his 17 campaigns in Punjab, Mahmud succeeded in pushing back the Buyids by a significant distance and bringing Khorezmia under his sphere of influence.

Although Mahmud's battles in India were only profane raids and not religiously motivated wars for Islam , his reputation as a "hammer for the infidels" was still propagated to Baghdad and beyond.

Because the Qarakhanids in Transoxania did not pose too much of a threat due to their internal disputes, Mahmud was also able to fight the Shiite Buyids in the west in the period that followed . A “liberation” of the Abbasids from their predominance did not take place with the death of Mahmud.

Mahmud of Ghazni died on April 30, 1030, leaving an empire that comprised the Punjab, parts of Sindh including a number of Hindu states in the Ganges Valley that had recognized Mahmud's supremacy, present-day Afghanistan including Ghazna, northern areas of present-day Balochistan, Gharjistan and Ghor, where local rulers had also recognized their supremacy, included Sistan , Khorāsān, areas of today's Iran, Tocharistan and some border regions on the Oxus.

Masʿūd I.

Mahmud of Ghazni was followed for a short time by his son Muḥammad, who was contested for power by his brother Masdūd. Masʿūd - a victorious general of his father - was also favored by the army. An army sent by Muḥammad against Masʿūd deserted to Masʿūd's side. As a result, Muḥammad was blinded and captured, and Masʿūd took the throne.

Masʿūd was addicted to drinking and lacked his father's diplomatic skills. Nevertheless, he continued his father's campaigns in India and pushed the Buyids back further. For a short time he owned Kerman (1035). From a military point of view he was in a worse position than his father, at the time of whom there was no comrade of the same caliber in all of Persia. At the time when Masʿūd ascended the throne, however, the Seljuks began to cross the Oxus and gradually occupy Khorāsān. Masʿūd's resistance was not very successful. The reasons included the absence of much of his army, which was deployed in the Five Rivers Country (Punjab) and the ethnic diversity of his armed force, which consisted mainly of Iranians of different origins and Indian peoples of the empire. The well-trained and experienced Turkish military slaves were only sparsely represented.

On May 23, 1040 Masʿūd's army was decisively defeated at the Battle of Dandanqan by the Seljuks under Toghril . Masʿūd was plotted on his retreat to India and killed in prison in 1041.

Late period

So Khorāsān was essentially lost to the Seljuks and the Ghaznavids concentrated on their remaining dominions and northwestern India. Ghazna and Lahore became the only two mints.

Maudūd b. Masʿūd (1041-1048) attempted to recapture Chorāsān in 1043/4 , but was defeated and only planned a new major attack shortly before his death. He was very busy keeping his empire together. The province of Sistan was lost to the local Nasrid dynasty as early as the 1030s , which subordinated itself to the Seljuks and with their help rejected Maudūd (1041). In addition, the Seljuks in 1042 intervened in Khorezm and distributed with the prevailing Oghuzen-Prince Shah Malik an ally of the Ghaznavids. Despite the lack of success, Maudūds prestige is said to have been so great that a Qarakhanid ruler of Transoxania submitted to him.

Also ʿAbd ar-Raschīd bin Maḥmūd (1048-1052) and Farruchzād bin Masʿūd (1052-1059) vigorously opposed the Seljuks and were able to achieve successes against Toghril's brother Chaghri Beg († 1060) and his son Alp Arslan in the meantime, which ended initiated the Seljuk expansion in the east. Ibrāhīm b. Masʿūd (1059-1099) made a final attempt to regain Chorāsāns, with the Seljuq prince Uthmān being captured and Sultan Malik Shāh (1072-1092) dispatched an army to restore the balance of power (1073). As a result, there were peaceful relations and marriage ties between the two dynasties, with the province of Sistan remaining under the suzerainty of the Seljuks. Ibrāhīm b. Masʿūd's government was seen as a time of prosperity and consolidation.

The peace with the Seljuks made possible the Ghaznavids under Ibrāhīm and his son Masʿūd III. (1099–1115) another expansion in India. A general Masʿūds III. is said to have penetrated further across the Ganges than Mahmud of Ghazni during his raids (against the Gahadavala from Kannauj ).

After a dispute over the throne among the sons of Masʿūds III. Bahrām Shāh (1117-1157) was installed in his office by the Seljuq Sultan Sandschar (1118-1157) and shifted the center of the empire to the Punjab, to Lahore . Bahram Shah was obliged to pay an annual tribute of 250,000 dinars to Sanjar and recognition in the Chutba . Since the middle of the 12th century, his empire came under pressure from the Ghurid dynasty from what is now central Afghanistan. The dispute began when Bahrām Shāh had a member of this family, Quṭb ad-Dīn Muḥammad poisoned, and his brother Saif ad-Dīn Sūrī therefore advanced to Ghazna, where he was beaten and executed in 1149. Then a third brother named ʿAlāʾ ad-Dīn Ḥusain (1149–1161) established himself in Ghor, defeated Bahrām Shah three times and looted and destroyed 1151 Ghazna. Among other things, he had the corpses of earlier Ghaznavid rulers exhumed and cremated.

As a result, the Ghaznavid rule was practically limited to Lahore in the Punjab. With the conquest of the city in 1186, the last Ghaznavid ruler, Chusrau Malik, was overthrown by the Ghurids.

administration

The ethos of the Ghaznavids was strictly Sunni, and the sultans followed the law school of Hanafi . Sultan Mahmud always maintained good relations with the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, thereby strengthening the religious and moral requirements for his authoritarian rule. He gave gifts to the caliph and presented himself as the protector of orthodoxy, especially against the Shiite Buyids, the Ismailites of Multan and the Mutazilites of Rayy. His son Masʿūd continued this policy until the Ghaznavids were finally defeated by the Seljuks, who from then on acted as “protectors of the caliphate”.

The exercise of power by the sultan and the administrative state apparatus were within the Persian-Islamic tradition. The Sultan ruled as a despot and with "divine assistance" over all strata of the population, whose main task was to respectfully serve the Sultan and pay him taxes.

While the Ghaznavid army was largely dependent on Turkish military slaves, the administrative state apparatus was in the hands of Persian bureaucrats who carried on the Samanid traditions. The Iranization of the state apparatus went hand in hand with the Iranization of the lifestyle and high culture at the Ghaznavid court, and all important government posts, including that of the vizier , the war minister, and the finance minister, were continuously occupied by Persians .

The court language of the Ghaznavids was Persian, while diplomatic correspondence was basically in Arabic. All surviving contemporary writings are written in either Arabic or Persian, but later reports also show that the dynasty itself spoke Turki ("Turkish") until the reign of Masʿūd I (1031–41) . Compared to other Turkish rulers, the Ghaznavid sultans were highly cultured and educated. For example, ʾUtbī describes the fact that Mahmud was trained in religious studies, while the contemporary Persian poet Baihāqi emphasizes the interest of Mahmud's son Masʿūd in Arabic works and his extraordinary talent for Persian writing, language and rhetoric.

Culture, art and literature

The Ghaznavids were of Turkish origin, but the earliest rulers of the dynasty, starting with Sebük Tigin and Mahmud, were thoroughly "Iranized". The extent to which a “Turkish” identity was pronounced among them cannot be determined from the sources - all of which are written in Persian or Arabic. If there was any emphasis on it at all, then only in the very early years of the dynasty, because like many other Turkish families and rulers of that time, the Ghaznavids had quickly adopted the language and culture of their Persian masters, teachers and subjects, so that already very early on there was no longer any connection to her Turkish-Central Asian origins. In this respect they became a “Persian dynasty” and, following the example of the pre-Islamic Persians, developed into generous supporters of Iranian high culture. The court in Ghazna in particular was developed into a widely famous cultural center that attracted numerous scholars and poets from the region. But the Ghaznavids do not seem to have been privileged enough to employ really great poets at their court - the only exception was Firdausi . The polymath Biruni also worked at the court of the Ghaznavids.

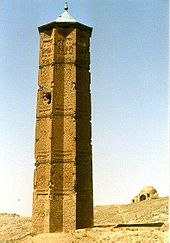

Art and architecture flourished during the Ghaznavid era - not only in Ghazna but also in Herat , Balch and other centers of the empire. On the one hand, this was due to the generous sponsorship by the sultans, and on the other hand, it was also due to the great financial opportunities that the Ghaznavids appropriated through their raids. Abū l-Fażl Baihaqī wrote an important historical work.

List of Ghaznavids

| Sebüktigin سبکتکین |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ismā'īl اسماعیل |

Maḥmūd محمود |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muḥammad محمد |

ʿAbd ar-Rashīd عبدالرشید |

Masʿūd I. مسعود اوّل |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maudūd مودود |

ʾAlī علی |

Farruchzād فرخزاد |

Ibrāhīm ابراهیم |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Masʿūd II. مسعود دوم |

Masʿūd III. مسعود سوم |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shīrzād شیرزاد |

Arslān Shāh ارسلان شاه |

Bahram Shah بهرام شاه |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chusrau Shah خسروشاه |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chusrau Malik خسروملک |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Leader of the Samanid ghulāmān-e chāṣ in Ghazna

- Alp-Tigin (962–963)

- Abū Isḥāq Ibrāhīm (963–966)

- Bilge Tigin (966-975)

- Böri Tigin ( pers: Pīrītegīn; 975–977)

Rulers (sultans) of Ghazna

- Abū Manṣūr Sebüktigin (977-997; initially ruled as governor on behalf of the Samanids in Khorasan)

- Ismāʿīl ibn Sebüktigin (997)

- Maḥmūd ibn Sebüktigin (Mahmud of Ghazni) (998-1030)

- Muḥammad ibn Maḥmūd (1030-1031; first reign)

- Masʿūd I. ibn Maḥmūd (1030-1040)

- Muḥammad ibn Maḥmūd (1041; second reign)

- Maudūd ibn Masʿūd (1041-1048)

- Masʿūd II. Ibn Maudūd (1048)

- ʿAlī ibn Masʿūd (1048)

- ʿAbd ar-Raschīd ibn Maḥmūd (1049)

Usurpation in Ghazna by the slave leader Abū Saʿīd Toghril (1052)

- Farruchzād ibn Masʿūd I (1052-1059)

- Ibrāhīm ibn Masʿūd (1059-1099)

- Masʿūd III. ibn Ibrāhīm (1099–1115)

- Shīrzād ibn Masʿūd III. (1115)

- Arslān Shāh ibn Masʿūd III. (1116)

Seljuks occupy Ghazna (1117)

- Bahrām Shāh ibn Masʿūd III (1117–1150; first reign)

Ghurids occupy Ghazna (1150)

- Bahrām Shāh ibn Masʿūd III. (1152–1157; second reign)

- Chusrau Schāh ibn Bahrām Schāh (1157–1160; only in northwestern India)

- Chusrau Malik ibn Chusrau Schāh (1160–1186; only in northwest India)

Conquest by the Ghurids (1186)

literature

- Clifford Edmund Bosworth: Ghaznavids . In: Encyclopædia Iranica

- Clifford Edmund Bosworth: The Ghaznavids. Their empire in Afghanistan and eastern Iran 994-1040 . Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1963 ( History, philosophy and economics 17, ZDB -ID 1385726-5 ).

- GE Tetley: The Ghaznavid and Seljuk Turks. Poetry as a Source for Iranian History . Routledge, London et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-203-89409-5 ( Routledge studies in the history of Iran and Turkey ).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ghaznavids

- ↑ Iqtidar Alam Khan: Ganda Chandella. In: Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. 2007, p. 66.

- ↑ The Making of Medieval Panjab: Politics, Society and Culture c. 1000-c. 1500.

- ^ RGT to Rajasthan, Delhi & Agra, p. 378.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i C. E. Bosworth : Ghaznawids . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume X (6), pp. 578-583, as of December 15, 2001 (English, including references)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Bertold Spuler : Ghaznawids. In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (fee required).

- ↑ Monika Gronke : History of Iran. From Islamization to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 31 ff.

- ^ A b Robert L. Canfield: Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. School of American Research Advanced Seminars, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2002, p. 8: "The Ghaznavids were essentially Persianized Turks who in the manner of the pre-Islamic Persians encouraged the developement of high culture."

- ^ A b B. Spuler: The Disintegration of the Caliphate in the East. In: PM Holt, Ann KS Lambton, Bernard Lewis (eds.): The Central Islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War (= The Cambridge History of Islam. Volume 1a). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1970, p. 147: "One of the effects of the renaissance of the Persian spirit evoked by this work was that the Ghaznavids were also Persianized and thereby became a Persian dynasty."

- ↑ CE Bosworth: Samanids. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (fee required): “One role which Ismā'īl inherited as ruler of Transoxania was the defense of its northern frontiers against pressure from the nomads of Inner Asia, and in 280/893 he led an expedition into the steppes against the Qarluq Turks, capturing Ṭalas and bringing back a great booty of slaves and beasts. "

- ↑ Jürgen Paul: Introduction to the history of the Islamic countries. University of Halle ( PDF handout ): "The rulers named 'Ġaznavids' in western research are named in the sources after their founder Āl-i Sebüktegin ..."

- ↑ Ghaznavids. In: J. Meri (Ed.): Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, London et al. 2006, p. 294 ( online ): "The Ghaznavids inherited Samanid administrative, political, and cultural traditions and laid the foundations for a Persianate state in northern India."

- ↑ Bertold Spuler : Ghaznawids. In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (fee required): “Masʿūd's resistance had little success; considerable parts of his army were engaged in the Pandjāb, and his forces were made up of very diverse elements: Iranians of various races, and also Indians; his own fellow Turks were only sparsely represented. "

- ^ CE Bosworth: Saldjūkids. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (fee required).

- ↑ Cf. Josef Matuz: The Emancipation of the Turkish Language in the Ottoman State Administration ( PDF; 1017 kB ), with reference to CE Bosworth: The Ghaznavids. Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran, 994-1040. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1963, p. 56.

- ↑ a b A. Wink: Al-Hind. The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Vol. 2: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest, 11th-13th Centuries. Brill, Leiden 1997, p. 112: "In so far as there is any emphasis on the Turkishness of the Ghaznavids and their following, it comes from the very early years of the dynasty. Later Ghaznavid chronicles in Arabic and Persian still corroborate that the dynasty spoke Turkish (Turki) up to the time of Mas'ud (1031-41) ... "

- ^ G. Tetley: The Ghaznavid and Seljuk Turks. Poetry as a Source for Iranian History (Routledge Studies in the History of Iran and Turkey). Routledge, London 2008, p. 32 ff.

- ^ David Christian: A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia. Blackwell, 1998, p. 370: "Though Turkic in origin [...] Alp Tegin, Sebuk Tegin and Mahmud were all thoroughly Persianized".

- ↑ Ehsan Yarshater: Iran II. Iranian History (2): Islamic period . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume XIII (3), pp. 227–230, as of December 15, 2004 (English, including references) “Although the Ghaznavids were of Turkic origin […] as a result of the original involvement of Sebüktegin and Mahmud in Samanid affairs and in the Samanid cultural environment, the dynasty became thoroughly Persianized [...] In terms of cultural championship and the support of Persian poets, they were far more Persian than the ethnically Iranian Buyids ".

- ^ CE Bosworth: Ghaznawids . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume X (6), pp. 578-583, as of December 15, 2001 (English, including references) "Sources, all in Arabic or Persian, do not allow us to estimate the persistence of Turkish practices and ways of thought amongst them [...] Persianization of the state apparatus was accompanied by the Persianization of high culture at the Ghaznavid court ".

- ↑ Bertold Spuler : Ghaznawids. In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (fee required): "As far as can be seen, the dynasty assimilated Persian influence in the realms of language and culture as quickly as did other Turkish ruling houses".

- ^ CE Bosworth: Ghaznawids . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume X (6), pp. 578-583, as of December 15, 2001 (English, including references) “As far as can be seen, the dynasty assimilated Persian influence in the realms of language and culture as quickly as did other Turkish ruling houses. But, leaving Firdawsī aside, they were not privileged to have a really important poet at their court. "

- ↑ al-Biruni. In: Encyclopædia Britannica Online, accessed July 20, 2015.

- ↑ The claim in Tarich-i Guzida that Alp-Tigin ruled Ghazna for 16 years is a mistake. Cf. Gavin Hambly (Ed.): Zentralasien (= Fischer Weltgeschichte . Volume 16). Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1966, p. 329, note 13.

- ^ CE Bosoworth: Böri . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume IV (4), p. 372, as of December 15, 1989 (English, including references)