gladiator

Gladiators (from Latin gladiator , to gladius for " [short] sword ") were professional fighters in ancient Rome who fought against each other in public displays. The fight of gladiators against each other is known as gladiature . Gladiator fights were part of Roman life from 264 BC. Until the beginning of the 5th century after Chr.

origin

The origin of the games is not fully understood. It is believed that gladiator fights had a religious meaning in the context of funeral celebrations . According to Roman sources, the gladiator games were of Etruscan origin. However, scenes from Etruscan funeral games that could be interpreted as gladiator fights are missing. However, tomb paintings from Paestum in Campania from the 4th century BC show Fighting between two armed men, in which a third person is sometimes shown, who is interpreted as a referee. Therefore, the origin of the games is now believed to be in Campania, which the Etruscans ruled at that time.

First gladiator games

The first recorded gladiator games in Rome took place in 264 BC. When Decimus Iunius Pera and his brother, in memory of their recently deceased father Decimus Iunius Brutus Pera , had three pairs of slaves fight against each other in the Forum Boarium , a market square in Rome, who were selected from 22 prisoners of war. The example was soon followed by other Roman nobles who also honored their deceased with these performances called munus ("service", plural: munera ). Since this form of gladiator fights was held next to the pyre, the gladiators were also called bustuarii (from the Latin bustum "pyre"). The Roman philologist Servius wrote:

“It was the custom to sacrifice prisoners on the graves of brave warriors; When the cruelty of this custom was evident to all, it was decided to let gladiators fight in front of the tombs [...] "

Despite this quotation, the thesis that gladiator fights were the milder variant of Greek and Roman human sacrifices in honor of the deceased is, according to some historians, incorrect. Rather, they are of the opinion that the bloody battles were intended to demonstrate the characteristics of the deceased, those characteristics which, according to the understanding of the people of the time, determined the greatness of the Roman Empire: courage, strength, bravery, determination and equanimity towards death.

These gladiator fights were organized by wealthy private individuals - they were the only ones able to afford both the costs of the gladiators and the lavish feast that followed. In the course of time, Roman politicians in particular discovered that organizing such munera was a suitable means of gaining recognition from the Roman population. The spectators followed the action standing close together at the edge - there were no grandstands at the first events.

Gladiator fights in the 1st century BC Chr.

As the popularity of gladiator fights increased among the Roman people, and when it was recognized as a right to be entertained in this way, the games became more grand and larger. Shortly afterwards, the first wooden grandstands were built and the first animal hunts (venationes) were added to the munera . Both extensions to the program gradually developed into an integral part of the events. The organizers were still wealthy private individuals, who welcomed any occasion to gain the respect of the Roman people in this way. And the more extraordinary the event, the sooner the wealthy rose in popular favor.

From Julius Caesar was narrated that he has had to equip its gladiators with armor made of silver, to impress the Roman population. Sueton , a Roman biographer, reported about Caesar about the extent to which such an attempt at bribery by the Roman population could take on:

“Caesar put on shows of all kinds: a gladiatorial play, theatrical performances in every district by actors of all languages, also circus performances, athletes' fights and a sea battle ( naumachie ). In the gladiatorial game at the Forum, Furius Leptinus, who came from a family of Praetorian rank, fought against the former senator and lawyer Quintus Calpenus […]

The hunted animals lasted five days; The end was a battle in which two detachments of five hundred men on foot, twenty elephants and three hundred horsemen faced each other [...] "

Roman Empire

Gladiator fights as a public task

While chariot races, theatrical performances and animal baiting were seen as a public task, gladiator fights were until 44 BC. A purely privately financed matter. This changed in the time of the state crisis after Caesar's assassination. For the first time this year, the aediles decided not only to host chariot races in public, but also to host gladiator fights. They took place as part of the ludi Cereales , the celebrations in honor of the goddess Ceres . These first publicly funded gladiator fights were accompanied by animal baiting .

Gladiator fights as an imperial privilege

It was above all Augustus who established the organization of gladiator fights as an imperial privilege:

“I had gladiator games organized three times in my own name and five times in that of my sons or grandchildren. About ten thousand people fought at these games ... I had animal baiting with African predators carried out in my name or in that of my sons and grandchildren in the circus or in the forum or in the amphitheater for the people twenty-six times, with about three thousand five hundred animals being killed. "

The organization of gladiator fights was increasingly integrated into the imperial cult - this was particularly true in the provincial cities. In the days of Augustus it was still possible for the senators to hold such games, but as early as 22 BC. Augustus issued a decree stating that in these cases no more than 120 gladiators could be used. At the same time, Augustus limited the number of days on which gladiatorial games could be held:

- from December 2nd to 8th;

- on the days of " Saturnalia " between December 17th and 23rd at the winter solstice;

- for the spring festival “ Quinquatrus ” between March 19 and 23.

Anyone who dared to hold gladiatorial fights privately ran the risk of incurring the wrath of the Roman emperors, given their increasingly closer connection with the imperial cult.

The relative rarity of the elaborate and costly gladiator fights has remained largely constant over the centuries. In AD 354, 102 of the 176 feast days were used for theater performances, 64 for chariot races and only 10 for gladiator fights.

Special features of the gladiatorial life

Genera of gladiators

The gladiators' first equipment was simple: each one wore a shield and a sword, and was protected by helmets and greaves. Over the centuries a number of different types of gladiators developed, some of which differed significantly in their equipment. The main equipment consisted of a sword , greaves , a helmet , a shield and a metal belt that was supposed to hold the loincloth . Most gladiators also had arm protection. The fighters rarely wore (upper) body protection.

More recent findings on the diet of gladiators, which anthropologists from the Austrian Archaeological Institute have obtained from bone analyzes during excavations of a gladiator cemetery in Ephesus , indicate that some gladiators tried to cushion themselves against minor injuries with natural layers of fat. So they didn't all look slim and well-trained. The reason for the fat pads and the strength of the gladiators is to be found in their special diet. In ancient Rome they were known as "grain crunchers" or "barley eaters", as many ate almost exclusively grain and beans . This diet probably explains the frequent occurrence of dental caries on the skeletons of gladiators. Corresponding studies also confirmed the habit of gladiators, mentioned in ancient sources, of drinking a drink with vegetable ashes after training, as unusually high levels of calcium and strontium isotopes in the bones could be detected.

The most important gladiator types (gladiator types ) were: Samnit , Thracian , Hoplomachus , Murmillo , Retiarier and Secutor . Initially, the gladiator types named after peoples fought in the equipment of the respective ethnic group. The equipment was later refined. The Hoplomachus , possibly a further development of the Samnite, was a heavily armed gladiator with a magnificent helmet. The Murmillo wore a fish symbol (murma - species of fish) on the helmet. It was probably originally used against the Retiarier , who competed with a net, arm armor and a trident. Later the Secutor fought against the Retiarier. He wore a rounder and smoother helmet that the retainer's net could not get caught in.

There were also: Andabates (blind gladiator), Crupellarius , Dimachaerus (two daggers), Eques (mounted gladiator), Essedarius (chariot fighter ), Gauls , Laquearius (lasso fighter), Paegniarius (whip?), Pontarius (bridge fighter ), Provocator , Sagittarius (Archer), Scaeva (left-handed, e.g. as Secutor Scaeva ), Scissor (tube with blades on the left arm) or its possible successor, the Arbelas , Veles (lightly armed gladiator), Venator (fights against wild animals).

We draw our knowledge of gladiators and their weapons from written and literary sources and inscriptions (epigraphy). There are depictions of gladiators on tombstones, frescoes, etc. They are supplemented by preserved statuettes. Much knowledge about the weapons of the gladiators is due to the excavations in Pompeii .

Female gladiators

The British Museum in London has a relief that is dated to the 2nd century AD and was found in Halicarnassus , now Bodrum in Turkey. It shows two female gladiators who have just been honorably discharged from the arena - but not from the gladiator school - by the audience enthusiastic about the fight. This tie (stantes missio) was almost more than a victory, as it was extremely rare. Even the names under which these two gladiators (Latin gladiatrix ) appeared are known: Amazona and Achilla . Despite this traditional illustration, which shows the two combatants wearing provocatores' outfits , female gladiators were the exception in gladiator fights. Nero had already had women (and also children) fight against each other and against people of short stature, but normally the use of these groups of people served more to amuse the audience.

The use of female gladiators contradicted too much the basic idea of the gladiators that those fighting in the arena demonstrated the ancient Roman military virtues of courage, steadfastness and the will to win. Because of this, there were not many supporters for women's struggles. Emperor Septimius Severus banned the use of female gladiators in AD 200.

Social origin of the gladiators

The first fighters were slaves or prisoners of war . Even later, mainly prisoners, convicted criminals (damnatio ad ludum gladiatorium) and slaves were used as gladiators. Already in the 1st century BC Free citizens also committed themselves as gladiators. Although gladiators were socially even lower than slaves, the interest in becoming a gladiator was temporarily so high that the Senate tried to restrict this through a law. Towards the end of the republic almost half of the gladiators are said to have been formerly free citizens who gave up their freedom when they entered the gladiatorial profession. This goal can be better understood against the background of the generally short lifespan of people at the time. A gladiator only had to fight one to three times a year, was well looked after during the rest of the time and was able to determine the conditions of his assignment himself.

The medical care that was given to the gladiators was also exemplary. One of the most famous doctors of antiquity, Galen , gained his experience during the time he was supervising the fighters in the gladiator school of Pergamon .

For those who volunteered for gladiatorial service, the historian Fik Meijer draws parallels with the nobles who volunteered for the French Foreign Legion during the 19th and 20th centuries :

“Their situation can perhaps best be compared with that of some of the seedy aristocrats in the 19th and 20th centuries who signed up for service in the French Foreign Legion. Like the legionnaires of modern times, these Roman aristocrats wanted to draw a line under their previous lives and opted for an existence in which their previous status no longer had any meaning. From then on they shared their lives with proletarians and slaves, whom they might not have looked at before. "

Life expectancy of a gladiator

That the gladiators started the fights during the imperial era with the greeting: Ave Caesar, morituri te salutant ("Heil you, Kaiser, die dozen [literally: those who will die] greet you") is a widespread legend that not the Corresponds to facts. This greeting has only been handed down for a single event in the year 52, when Emperor Claudius organized a sea battle ( naumachie ) between several thousand convicts, i.e. not between gladiators, who greeted him with these words. With these words you probably tried to arouse the emperor's pity. Research believed that this was the only occasion that this phrase was used. The chance of convicts to survive such an exhibition match was much lower than that of a gladiator. Their life expectancy fluctuated considerably over the centuries. In the 1st century BC, i.e. during the Roman Republic, when the Roman nobles bought the favor of the electorate through generous munera , the blood of gladiators was also treated generously. Juvenal commented at the beginning of the 2nd century AD:

"Munera nunc edunt et, verso pollice vulgus cum iubet, occidunt populariter"

"Now they give gladiator fights and, as the mob demands with twisted thumbs, they popularly kill."

Overall, there is little reliable data from the time of gladiator fights about how great a gladiator's chances were of leaving the arena alive. The historian Georges Ville evaluated 100 fights that took place in the 1st century AD and found that 19 gladiators (out of 200 fighters involved) lost their lives in these 100 fights. According to evaluations of gravestones, the average age at which they died was 27 years. Gladiators would have had a life expectancy that was well below the average of the ordinary Roman citizen if they had survived the disease-prone period of childhood.

The historian Marcus Junkelmann points out that only the most successful gladiators were tombed. The majority of gladiators, on the other hand, died at the beginning of their careers, as only the most capable survived the first fights. These newborn gladiators, who died young, were usually buried anonymously or placed in mass graves. According to Junkelmann's estimates, most gladiators died their violent death between the ages of 18 and 25.

With each fight, a gladiator's confidence, experience, and popularity increased. An experienced gladiator with a high following had significantly more chances of being pardoned by the audience or game organizer if he was defeated in a fight. The survival of an experienced fighter was entirely in the public's own interest - this was the only way to ensure exciting fights in the future. According to the inscriptions on the tomb of a gladiator buried in Sicily, this gladiator won 21 out of 34 fights, nine fights ended in a draw, and in the four fights that he lost, the audience pardoned him.

Since gladiators were entitled to part of the income from their fights, they had a certain chance of buying themselves out if they survived longer. Released gladiators were awarded a wooden stick or sword (rudis , literally "mixing spoon").The strict Roman hierarchy offered gladiators little freedom for a life after the arena. Often they became instructors of new gladiators, an activity that could lead to that of a lanista ( master gladiator); in times of crisis such as For example, in the Danube regions in AD 68/69, they were also sought-after trainers for quickly recruited recruits in order to teach them the craft of war in a crash course, so to speak. Furthermore, many members of the Roman upper class considered it chic to be trained in gladiature by an experienced fighter, similar to how one learns a martial art today. Using gladiators as bodyguards was prestigious and likely efficient.

Gladiator schools

Gladiators were trained in special schools (ludi) . Famous gladiator schools were located in Capua and in Pompeii, which was buried by a volcanic eruption in 79 AD . One of the largest gladiator schools was in Ravenna . It is estimated that there were a little more than 100 gladiator schools in total, which were usually under the direction of a master gladiator who was also the owner of the gladiator school. Often gladiators traveled from town to town in a troop (familia) . The owner of the troop rented his gladiators to anyone who wanted to organize a gladiatorial fight.

There were four gladiator schools in Rome, the largest of which was called Ludus Magnus and was connected to the Flavian Amphitheater, later known as the Colosseum , by a tunnel. These four were state owned and under the supervision of a carefully selected civil servant who was one of the highest paid Roman civil servants. In view of the danger posed by a death-defying, battle-hardened group of people, the aim was to ensure that the risk to the Roman population was kept to a minimum.

The trainers of a newly recruited gladiator were usually old, experienced fighters who trained their students in the movements typical for the respective branch of arms. The students practiced on stakes, and in the 4th century Vegetius described the training practice that was identical for soldiers and recruits:

“But each of the recruits drove a stake into the ground so that it could not wobble and was six feet high. At this post the recruit practiced as if against an opponent [...] so that he sometimes directed the attack as if against the head and face, sometimes threatened from the flank, sometimes tried to wound the hollows of the knees or legs [...] in this In practice, the precautionary measure was that the recruit would jump up to make a wound without exposing himself anywhere to wound. In addition, they learned not to hit, but to stab ... A struck wound, with whatever force it may be inflicted, is not often fatal, since the vital organs are protected by the protective weapons and by the bones. On the other hand, a sting that is only two inches deep is fatal [...]. "

The gladiators usually practiced with wooden weapons, U. were a little heavier than those that were later used in the arena. This trained their endurance.

Expiry of a day in the arena

Preparations

If there was a munus , the game organizer (editor) turned to a gladiator master (lanista) and commissioned him to carry it out. A contract stipulated how many pairs of gladiators had to compete, what the accompanying program looked like, how long the event should last, and also regulated payment.

A few days before the start of munus , the fighters were presented to the public. Important information for the spectators was in which pairings the fighters would compete against each other, in which order the fights would be carried out and in how many fights the respective gladiators had already been successful. The evening before, there was a banquet for the gladiators, which was also open to the public.

Fight day

Just as Augustus established the organization of gladiator fights as an imperial privilege, he also had a decisive influence on the course of a gladiator fight. He tied the animal baiting , which was held as an independent event up until the Augustan era , into the course of a day of fighting. The course of the individual gladiatorial contest was not binding; typical for a day in an amphitheater in the post-Augustan imperial period, however, was the following sequence:

- In the morning hours the first animal fights (venationes) were held, in which not gladiators fought, but special venatores and bestiarii . These specially trained fighters were seen even less than gladiators, they also wore completely different equipment. Her weapon was primarily the hunting spear. Initially harmless animals such as antelopes or deer were hunted. Once these were killed, the hunt for more dangerous animals such as big cats, elephants and bears began. The poet Martial, for example, reports on fights between bull and elephant, lion and leopard, or rhinoceros and buffalo. In addition, numerous other, preferably exotic species such as giraffes were brought into the arena.

- Occasionally circus acts followed as an interlude, in which trained animals appeared.

- During lunchtime criminals were executed in the arena. This could be an execution in which the criminals were accused of the animals (which was a condemnation damnatio ad bestias ) or they were forced to fight each other with weapons (which meant a condemnation damnatio ad ferrum ). The winner of a duel then had to face the next convict. There was no chance of a pardon; the last survivor was executed in the arena by venatores ( munera sine missione ). Another execution variant consisted in the hopeless encounter of the condemned against a regular gladiator (damnatio ad gladium) .

- The afternoon program began with the marching in of all the gladiators who presented themselves to the audience. After the presentation, they returned to the catacombs.

- As a preliminary exercise (so-called prolusio ) to the actual gladiator fights, gladiators, but also occasionally representatives of the nobility, competed in pairs with blunt or wooden weapons in order to be able to demonstrate their techniques and advantages. In the case of very large events, this prolusio could extend over several days. A participation of a Roman nobleman in such a prolusio was, in contrast to the "real" gladiatorial fight , considered dishonorable. Even Roman emperors - such as Commodus as secutor - are said to have displayed their courage.

- The actual gladiatorial match took place after the exhibition matches. The duel was common, with certain pairings such as a retiarius versus a secutor or thraex versus murmillo being classic combinations.

struggle

The historian Junkelmann points out that fighting in the arena - the so-called gladiature - was not a wild scuffle, but a highly differentiated martial arts subject to precise rules. Forensic analyzes of the bones of dead gladiators also suggest this. The fight was usually observed by two referees. They also instituted breaks when both fighters were too exhausted or the equipment straps came loose; and they punished rule violations. One of the essential tasks of the referees was to prevent a surrendering gladiator from being exposed to further attacks by his opponent. A fight could end in four ways:

- by the death of one of the opponents during the fight;

- by the fact that one of the losers gave up and at the request of the audience or the game organizer was killed by his opponent in the arena (if he fought well, he was usually free; if previous fights had been bloodless, the audience wanted to see someone die at some point) ;

- Surrender of one of the fighters and pardon the gladiator by the audience or the game organizer (so-called missio );

- the decision that the battle ended in a draw (stantes missi) .

According to Junkelmann, the last form of ending a fight was the rarest and was considered quite glorious.

Fewer gladiators died in the arena than previously thought - probably one in eight died. Because if a gladiator was killed, the organizer of the games had to get a new gladiator - and these were expensive.

An inferior gladiator asked for mercy by holding out a forefinger or laying down his arms. The referee then turned to the organizer of the games - in the Roman Colosseum this was usually the emperor who had to make the judgment. This usually passed the decision on to the viewers. In the general performance, viewers passed the death sentence by pointing their thumbs down. Since the concepts of heaven (kingdom of the good) and hell (kingdom of the evil) did not exist in the pre-Christian world of Rome, it is just as likely that a death sentence was expressed with the thumbs up - as a symbol for the distance from mother earth has been; analogously, in the opposite direction, the thumb stretched downwards was a sign of remaining on this earth. There is no historical evidence that this was so. It is also conceivable that the fatal blow was symbolized with a thumb pointing towards the chest or throat, since the fatal blow was carried out with the sword from the collarbone into the heart. What is more clearly documented is what the Roman spectators shouted at such moments. If they called in the middle (let him go) or missum , then the defeated gladiator was allowed to leave the arena alive. The call iugula ( stabbing ), on the other hand, announced the end of the gladiator by execution. The inferior gladiator was expected to kneel on the ground and take the death blow in the neck or between the shoulder blades. This was practiced in the gladiator schools.

The victor received an olive branch and an amount of money and left the arena through the Porta Sanavivaria , the gate of health and life. The deceased, on the other hand, was carried out through the Porta Libitinaria on a bier hung with cloths - the gate of Venus Libitina , the goddess of death and burial.

Romans and gladiators - an ambivalent relationship

Example of manly bravery

The attitude of the Romans towards gladiators was very ambivalent: on the one hand, gladiators were even lower in the social hierarchy than slaves , on the other hand, successful gladiators became celebrities, from whom one can see the ancient Roman virtues such as will to win, contempt for death and Had bravery demonstrated. For both Cicero and Seneca , the indifferent dying gladiator was an exemplum virtutis , an example of manly bravery. Marcus Junkelmann points out that Cicero is what he preached to the Roman people in his Third Philippine Speech in view of the grip of Marcus Antonius for power

"[...] what brave gladiators show by going down with dignity, let us do that too, masters of all countries and peoples - we would rather be honored than lead the lives of slaves in disgrace"

also implemented for himself. He died the "gladiatorial death" by willingly offering his neck to the sword when the mercenaries of Antony caught him.

"Adored" gladiators

Some gladiators had a large following among the citizens of Rome and were coveted by women. The Latin term Gladius , from which gladiator is derived, had, in addition to its original meaning "thrusting sword", an obvious sexual use in vulgar language. Graffiti such as can be found in Pompeii suggest ardent followers of the gladiators. Sleeping with gladiators was frowned upon and was strictly socially outlawed, but it happened anyway. Gladiators enjoyed a reputation in Roman society similar to today's pop stars . The game organizer's feast the evening before a fight gave the city's influential women the opportunity to get to know their idols personally and often intimately. Faustina, the mother of Emperor Commodus , allegedly fathered her son with a gladiator - but Commodus probably invented this story himself to underline his special role. The relationship between Eppia, a woman from a rich family who was the wife of a senator, and the gladiator Sergiolus was felt to be particularly scandalous. If the Roman satirist Juvenal is to be believed, Eppia followed Sergiolus, who was no longer physically attractive for a long time, back and forth across the provinces out of love.

Spartacus or the danger in your own city

Gladiators were highly trained, battle-hardened men with little to lose. For a long time the Romans assumed that there was little danger to them from the gladiators. The men came from different ethnic groups, and as long as the weapons in the armory were under strict guard and the gladiators were inaccessible outside of their practice time, the danger was considered to be low. This changed with the slave revolt, in the emergence of which gladiators played a key role. In 73 BC Eighty gladiators escaped from a gladiator school in Capua and were quickly joined by other slaves. Initially armed only with kitchen knives (the weapons in the closely guarded armory were not accessible during the outbreak), the escaped quickly came into possession of professional equipment after twice successfully taking possession of the weapons of the troops assigned to them. The initial military successes of the slave army, which was largely under the leadership of Spartacus , did not last . 71 BC The slave army in the extreme south of Italy was confronted with three Roman armies under Crassus, Pompey and Lucullus. Spartacus faced Crassus and was defeated by him in open battle, the slave army was largely wiped out and Spartacus was killed. Scattered remnants of the slave army were destroyed by the approaching army of Pompey; another 6,000 slaves who were captured were later crucified along the Appian Way.

The Romans long remembered the danger of a renewed uprising by armed gladiators. The gladiator schools in Rome were placed under the supervision of imperial officials (so-called procuratores ) who were highly paid. In times of state crisis it was preferred to move the gladiators out of the cities to prevent further uprisings of this kind.

Venues of gladiator fights

The Forum Boarium - the cattle market near the Tiber Island - was the first venue for gladiator fights, which were initially just simple, primitive events. For reasons of space, the Roman Forum was more suitable than the Boarium Forum and was therefore the scene of the gladiator fights, the number of which began in 264 BC. Chr. Increased continuously. For other cities such as Cosa , Paestum and Pompeii , gladiator fights are occupied on the main city squares. Just a few years after Decimus held his special memorial service for his father, seating was created for the audience so that they could watch the action with a little more comfort.

Walled amphitheaters were developed in Campania in order to offer the best view of the fighting to large crowds of spectators . Soon they were being emulated in other parts of the Roman Empire as well.

In contrast to numerous other cities in the empire, Rome itself did not have a suitable place for gladiator fights for a long time. That only changed with the construction of the Colosseum , with which a huge, sand-strewn arena (the term arena comes from Latin and means "sand") was created, from whose tiers the Roman spectators could follow the action.

Existing theaters were converted for gladiator fights, particularly in the east of the Roman Empire . Sometimes, as in Ephesus , small arenas were built into stadiums.

The End

Among the Roman emperors there were not only great friends of gladiatorial fights (such as Commodus , Caligula and Claudius ) but also those who were distant from this hustle and bustle ( Tiberius or Marcus Aurelius ). Marcus Aurelius, for example, banned the use of sharp weapons in gladiatorial fights, and Augustus banned gladiatorial fights that could only end with the death of one of the combatants. There were no decisive opponents of the gladiatorial fights: the imperial cult and the gladiatorial contest were closely interwoven. Those who spoke out against the gladiatorial fight also spoke out against the institution of the emperor. For Seneca as well as for Cicero, the gladiator, who dies indifferently and bravely in a fight against another gladiator, symbolized Roman cardinal virtues in exemplary form.

It is often assumed that philosophers rejected the gladiatorial fights, but critical voices were only directed against the unrestrained bloodlust of the audience and the brutal accompanying program. Seneca reports disgustedly about the midday executions, in which the executives competed against each other with sharp weapons:

“By chance I was in the circus' lunch program - expecting jokes, jokes and a little relaxation, with which people's eyes can recover from human blood: the opposite is the case. In the previous fights there was still room for pity; Now you leave the games and it is pure murder: you have nothing to protect yourself. Subjected to the blow with the entire body, she hits every blow. Most prefer this to the regular fighting couples and other popular ones. Why shouldn't they prefer it? Not helmet, not shield rejects the sword. Why feint? All of this is delay in death. In the morning, people are thrown to the lions and bears, and at noon to the spectators. Murderers are charged with future murderers on their orders, and the victor they save for another murder; The end is the fighting death: the cause is fought with sword and fire. That happens until the arena is empty. "

Real and effective criticism of the gladiatorial fight did not begin until the Christian writers in the 2nd and 3rd centuries who, among other things , adopted and intensified the arguments of the Stoics , but above all referred to the biblical prohibition of killing. However, after the church father Augustine of Hippo had already compared the unshakable attitude of gladiators in the face of death with that of Christians and urged his fellow believers to adopt a “gladiatorial spirit”, it is possible that primarily humanitarian considerations were not a cause for the decline of the gladiatorial games, but because these spectacles, which staged virtue and the courage to death, were viewed as unsuitable competition for one's own faith. In 325 AD, the Christian emperor Constantine first issued an edict addressed to the governors of the eastern provinces:

“In times when there is peace and calm domestic politics, we dislike bloody demonstrations. That is why we decree that there can be no more gladiators. Those who were previously sentenced to become gladiators for their crimes will now work in the mines. In this way they atone for their crimes without having to shed their blood. "

Nevertheless, gladiatorial fights ( munera ) remained very popular throughout the fourth century and provided emperors and dignitaries with important opportunities for representation. However, it has become increasingly difficult to find gladiators since the use of Christians was banned in 365. The use of soldiers and veterans was also prohibited. This also increased the cost of the games, but initially they remained common. The Senator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus reported, for example, in a letter (Ep. 2.46) from the year 393 n. Chr., That of the Saxon to them slaves he had bought in Rome in honor of quaestorship fight his son to let , 29 would have escaped the fight the night before by suicide. At the beginning of the 5th century AD, the gladiator games were finally banned by the Western Roman Emperor Honorius ; The story handed down by Theodoret that this prohibition was preceded by the death of the monk Telemachus , who jumped into the arena to stop the fighting, is not very credible. It also took a while until the imperial ban actually prevailed, because gladiators are attested until the middle of the 5th century. Animal hunts ( venationes ), against which there were far fewer reservations on the part of the Christian, were held at least until the end of late antiquity in the 6th century and, together with chariot races, remained extremely popular events.

Persistence of the ritualized duel

The Dutch professor of ancient history Fik Meijer points out that the gladiatorial fight continued in ritualized duels into the 20th century. For the individual time periods he mentions:

- In the Middle Ages the “judicial” duel as a divine judgment, in which two men accused of a crime fought against each other. The defeat was proof of guilt: If the loser did not die in battle, he was then executed.

- Also to be assigned to the Middle Ages is the knightly duel, in which one of the participants died often enough.

- From the 16th century to the beginning of the 20th century, the duel occurs , which also takes place according to strict rituals.

- The modern boxing match or wrestling does not aim at killing the opponent, but the fascination it exerts on the spectators is not unlike that which a gladiatorial match exerted on the spectators of that time.

Marcus Junkelmann points out a decisive difference in these comparisons. The gladiator who lost the fight (if he did not die during the fight) was at the mercy of the gambler and the audience: the audience or the gambler could decide that he should be killed, and this was done in the form of a targeted, execution-wise killing.

The gladiator fights were always accompanied by executions and animal baiting. Here, too, Fik Meijer points out that the form of display was not limited to Roman times: executions were publicly carried out in Central Europe until the 20th century and were regularly no less cruel than what happened at lunchtime in the gladiatorial arenas . Animal baiting - the morning program of a gladiator fight - is a legal draw as bullfighting to this day; Dog fights u. The like are now prohibited by law, but still find an audience.

Artistic representation in modern times

The fascination that playing with death has on people has led literature , visual arts and film to deal with this topic since the 19th century . Edward Bulwer-Lytton published his novel The Last Days of Pompeii in 1834 , in which gladiator fights play a role. This novel was followed by others, including the novel Quo vadis by the author Henryk Sienkiewicz , published in 1895/96 , which a few years later was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature .

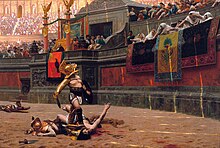

At the same time, the visual arts took on the subject. 19th-century painters such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema , Francesco Netti and Jean-Léon Gérôme painted subjects from the battle arena. The oil painting Pollice verso by Gérôme from 1872 is considered to be one of the outstanding works on the subject of gladiature, and as the image that decisively shaped our present-day ideas about gladiator fights.

The painter Gérôme had done extensive research and intensively studied armaments excavated in Pompeii. His painting therefore reflects the state of knowledge of the time about gladiator fights, only the combination of the items of equipment is not correct according to today's knowledge. The painting also (presumably) aptly reproduces the atmosphere of the decisive moment: under the light filtered through the awning, an excited crowd falls the execution sentence of the defeated fighter. Even the white-clad vestals , who always attended the gladiatorial fight, which is considered a state act, allow themselves to be carried away to the deadly gesture. Both the awning and the privileged seat of the Vestal Virgins are historically documented, only the direction of the thumb sign that indicates the death sentence is conjecture. Director Ridley Scott , who made the film Gladiator in 2000 , admitted that this painting inspired his film.

The film also took up the topic of gladiatorial combat very early on. One of the first films to feature gladiators is the 1935 film adaptation of the novel Quo vadis? Its continuation was the subject in classics like the film Spartacus by Stanley Kubrick and with Oscar winning blockbuster Gladiator in 2000.

Both Spartacus and Gladiator are incorrect in their portrayal of gladiator fights. While the film Spartacus restricts itself to competing gladiator types that did not yet exist at the time shown, Ridley Scott goes much further despite his published claim to paint an authentic picture. The pieces of armor used in the film come from different times and the arsenals of different peoples - the expert Marcus Junkelmann, who specializes in gladiator weapons, names Viking helmets and parts of Turkish armor, among other things; the fight depicted is a bloodthirsty slaughter and not a duel accompanied by referees, and the fighters are also allowed to deal with big cats that suddenly appear in the arena . Remarkable flaws can even be found in the equipment of the arena: the stone pillars serve as turning marks for racing teams and are therefore not to be found in the Colosseum , but in stadiums geared towards racing, such as the Circus Maximus .

swell

- Augustus: Res gestae divi Augusti / My deeds. Latin-Greek-German. Edited by Ekkehard Weber. Düsseldorf-Zurich 1999. (Also to be found as a web link in Latin / English under: Quote Augustus )

- Cicero: Tusculanae disputationes / Conversations in Tusculum II 41. ( Text (Latin) )

- Cicero: Epistolae ad familiares / To his friends VII 1. ( Text , Latin / English)

- Seneca: Ad Lucilium epistulae morales / An Lucilius. Letters about ethics. Book I, letter 7. ( Text , Latin)

- Suetonius: De vita Caesarum / The imperial servants. ( Text , Latin, Text , Latin / English)

- Vegetius: Epitoma rei militaris / Outline of the military system. Latin-German. Ed. And transl. by Friedhelm L. Müller. Stuttgart 1997 ( text , Latin)

literature

- Antikenmuseum Basel and Collection Ludwig (Ed.): Gladiator. The true story. Exhibition booklet Steudler Press, Basel 2019, ISBN 978-3-905057-39-3 .

- Alan Baker: Gladiators. Life and death fighting games . Goldmann Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-442-15157-0 (Goldmann-Taschenbuch 15157).

- Marcus Junkelmann : Playing with death. This is how Rome's gladiators fought . Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2563-0 .

- Eckart Köhne (Ed.): Gladiators and Caesars. The power of entertainment in ancient Rome . Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2614-9 .

- Christian Mann : The gladiators. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64608-9 .

- Fik Meijer: Gladiators. The game of life and death . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7608-2303-3 (a very detailed and readable summary of the various aspects of gladiatorialism).

- Fabrizio Paolucci: Gladiators. Life for triumph and death . Translated by Katja Richter. Parthas, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86601-602-6 .

- Erwin Pollack : Bustuarii . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume III, 1, Stuttgart 1897, Sp. 1078.

- Thomas Wiedemann: Emperors and Gladiators. The power of games in ancient Rome . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-534-14473-2 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gladiator - Duden , Bibliographisches Institut ; 2016

- ^ Suetonius, Caesar 39, 3 .

- ↑ Res gestae divi Augusti 22.

- ^ "City of Gladiators - Carnuntum ", 3SAT, December 28, 2016.

- ^ Latin-German concise dictionary

- ^ Suetonius, Claudius 21, 6 .

- ^ Donald G. Kyle: Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome . Routledge, London 1998, p. 94.

- ↑ Juvenal 3, 36-37 .

- ↑ Vegetius, Epitoma rei militaris 1, 11-12.

- ^ Fabian Kanz, Karl Grossschmidt: Head injuries of Roman gladiators. In: Forensic Science International. Shannon 160.2006,2-3 (Jul 13), pp. 207-216. ISSN 0379-0738

- ↑ Paolucci: Gladiators - Life for Triumph and Death p. 16.