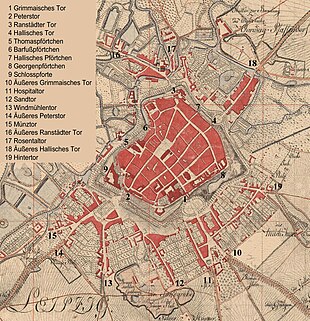

Leipzig city gates

The Leipzig city gates were from the Middle Ages to the 19th century existing structural mechanisms for regulating and control of people and goods in and out of the city of Leipzig also had defensive functions at first. In addition to the four main gates and the five well-known gates through the city wall , a number of so-called outer gates were added later, which controlled the access roads to the city as secondary gates. Nothing is left of any of the gates where they stood.

history

Since the Middle Ages, the city has been surrounded by two walls of different heights, the higher one being inside. Between the walls was the Zwinger, accessible around the city, and the water-filled moat in front of the outer wall . In four places there were gates with drawbridges . At the gates, the city wall was provided with horseshoe-shaped extensions for better defense. There were also some small gates.

After the siege of Leipzig in the Schmalkaldic War , the city fortifications were expanded in the middle of the 16th century, in particular with upstream bastions - here called bastions . A remnant of such a facility, mainly preserved underground, still exists today in the form of the Moritzbastei in the southeast corner of the old town on the inner city ring , which largely marks the outer course of the former city wall . The reinforcement of the city fortifications also required the gates to be redesigned. These were partly rebuilt and now also contained towers. After the Thirty Years' War there were further additions to the city fortifications and the gates were renewed. After Elector August III in 1763 . Based on the experience of the Seven Years' War, because of the loss of its strategic military importance, the city fortifications were demolished, and their removal began in the 1770s. The city gates were initially retained. Due to the expansion of the city, they were supplemented by outer city gates on the main access roads into the city. These side goals finally lost their importance in the founding years . At the beginning of the 19th century, the historic main gates became a traffic obstacle and between 1822 and 1831 they were dismantled except for the Peter Gate, which followed in 1860. Some side gates were preserved for a while as long as they were not an obstacle to traffic and did not stand in the way of the redesign of the suburbs from the middle of the 19th century. The rear gate on Schützenstraße was demolished in 1843 and the Zeitzer gate only in 1856.

Goal regulations

The gate regulations were developed over the course of centuries and are a reflection of the importance of the four main gates on Via Regia and Via Imperii for Leipzig as a trade and trade fair city.

Initially, in the Middle Ages, different laws applied to people passing through the gates in one direction or the other. In principle, city law ended at the city gates for people, traffic, craft and trade. Outside the city gates and on the streets and paths, the land law of the sovereign or the respective landlord applied . Due to its favorable location at the intersection of two central European old streets , Leipzig was granted special privileges . The city had enormous advantages from these privileges and the street constraints that had prevailed until almost modern times . Decisive for the handling of goods were the city's stacking rights and the imperial trade fair privilege of Maximilian I from 1497, renewed and expanded in 1507, which competed with other cities within 15 German miles (approx. 115 km) - especially Erfurt and Halle (Saale) - held in check. Trade and passenger traffic were thus directed to Leipzig.

At the city gates as the starting and ending points of the trade routes and country routes, the transport of goods into and out of the city was controlled and actually only registered here, for which the city gatekeepers and measurement assistants were responsible. They issued notes of what a wagon, cart or pack animal had loaded. The due duties were only collected on the market after the goods had been weighed in the old scales and the duty or excise had been calculated. In addition, there was the so-called “Budengeld” that the market traders had to pay for selling the goods on the market. Upon departure, the gatekeepers checked on the basis of the issued receipts from the market supervisor or the city treasury whether a trader had properly paid all customs and duties. Such gate receipts are important historical sources today in order to be able to reconstruct the flow of goods and the movement of people in and out of the city over centuries.

People were also checked at the gates. The names of the arriving travelers were published daily in a directory, the “gate slip”, when they checked in at the gates. In addition, a fee was payable at all city gates, which was called a "gate penny" and represented a kind of entrance fee into the city. It was an old institution similar to the bridge toll . The maintenance of the gates and the city fortifications were originally intended to be financed by the income . This also paid the gatekeepers, gatekeepers and the so-called “pullers” at the outer gates for operating the barriers or opening the gates. This tax is also comparable with road tolls , the levying of which was justified with the maintenance of the old roads that were later converted into chausseen .

The free movement of people and goods was literally not unlimited until 1824 and ultimately encountered considerable hurdles at the four inner city gates. Although the city wall was almost completely removed at the end of the 18th century, the moat in front of it still existed in many places. Over this, bridges led to the main gates, which also controlled access to the old town in this situation. For security reasons, the city gates were closed at night. This happened after 9 p.m. in summer and at 4.30 p.m. in winter. From the 17th century, anyone wishing to enter or leave the city during the closing time had to pay the aforementioned gatekeeper. This generally hated tax was abolished in 1824 in the course of the abolition of internal tariffs throughout the Kingdom of Saxony . On the occasion of this, there were spontaneous celebrations among the population and especially among the Leipzig students. As night owls in the pubs in the suburbs and villages in the surrounding area (especially Eutritzsch , Gohlis , Reudnitz ) they had always refused the gatekeeper. The lifting of the gate, the razing of the city gates and, last but not least, the gradual backfilling of the moat marked the beginning of the merging of Leipzig's old town with its suburbs.

The goals

Inner gates

The inner gates are those that lay in the course of the city wall and formed the historical entrances to the old city. Since the old trading routes Via Regia and Via Imperii crossed in Leipzig , four main gates were assigned to them, which also roughly coincided with the cardinal points. From these gates began with paved roads, so-called stone paths, which got their name after the gate and which, with the exception of the Hallische, still serve as street names. The four urban districts and the suburbs outside the gates were named after the gates. These suburbs were old urban settlements outside the old town that spread out just outside the city wall.

- The east-facing Grimmaische Tor (No. 1 on the map) serving as a dropout for the Via Regia was built between 1498 and 1502 as a double gate system in the city wall with a drawbridge over the moat. Beyond the ditch, the Grimmaische Steinweg began , which led out of town to the outer Grimmaischer Tor and the hospital gate. In 1577 the city fortifications at the Grimmaischer Tor were replaced by a stronger defensive system, which extended far into the suburbs and also contained a tower that served as a debt tower for defaulting payers in times of peace . In 1687 the main guard of the city was moved here from Ranstädter Tor. At the same time, the medieval gate building was replaced by a new one decorated with the Saxon spa coat of arms, and the square in front of it was laid out as a promenade . Today's Augustusplatz developed from this almost rural-looking “square in front of the Grimmaic Gate” . After the Grimmaische Tor was demolished in 1831, the confectioner Wilhelm Felsche bought the debt tower and the property adjoining the former gate and built the Café français there in 1835 , later Café Felsche . 1838 corner Grimmaischer Steinweg, which was on the court, New Post Office building of Albert Geutebrück (1801-1868) built.

- The Via Imperii led south through the Peterstor (No. 2), which was named after the St. Peter's Church next to it. It was first mentioned in 1420. The gate leading through a tower from the Middle Ages was replaced by a new baroque building in 1722/23. The design came from the master builder Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann (1662–1736). A stone arch bridge led across the city moat in front of the gate, which was already dry at the time. The gate contained guard rooms and apartments for city officials. It was considered one of the most beautiful baroque buildings in Leipzig, but was the last of the historic city gates to be demolished as a traffic obstacle in 1859/60.

- The Ranstädter Tor (No. 3) stood in the area of today's Richard-Wagner-Platz and was the west exit of the Via Regia. The gate was integrated into the Ranstädter Bastei as a double gate system, which was built between 1547 and 1550. Until 1687, the city's main guard was located at Ranstädter Tor - then at Grimmaischer Tor. The name comes from the places to be reached Markranstädt and Altranstädt . The medieval gate with a tower was demolished in 1822.

- The Hallische Tor (No. 4) leading to the north for the Via Imperii was built in 1692 and was of little defensive importance. In 1831 the gate was torn down. The street name “Am Hallischen Tor” between Brühl and the beginning of Gerberstraße remained as a memory .

Gates

In addition to the gates, the city wall also had several openings for passenger traffic. Because of the large distances between the city gates, they were primarily used to reach the western promenades facing the Pleiße .

- The Thomaspförtchen (No. 5) led from the Thomaskirchhof next to the old Thomas School to the Thomasmühle opposite .

- The barefoot gate (No. 6) was a narrow passage starting from the barefoot alley that led to a footbridge over the moat. (This former part of Barfußgäßchen is now called Kleine Fleischergasse.) The name of the gate goes back to the Franciscan monastery ( Barfüßer ) in this part of the city .

- The Hallisches Pförtchen (No. 7) was at the end of a street that was later called Plauensche Straße. In 2012 the area was built over by the Höfe am Brühl complex . The old street alignment of Plauenschen Strasse now forms a passage between the courtyards from Brühl to Richard-Wagner-Strasse.

- The Georgenpförtchen (No. 8) at the eastern end of the Brühl am Georgenhaus allowed easy access to the eastern parks with the Schneckenberg , the Swan Pond and the "Gothic Gate" (park decorations in the form of neo-Gothic ) in the so-called " English enclosure ".

- The castle gate (No. 9) was a direct access from outside the city to the Pleißenburg . This was made possible when the Pleißenburg gradually lost its military importance after the Thirty Years' War .

The Hallische Pförtchen 1795,

in the background the Old Theater

Outer gates

The outer city gates first became necessary when the city expanded beyond its walls, and lost their meaning in the second half of the 19th century when these too were overwhelmed by the city's growth. Structurally, they were not as elaborately designed as the inner city gates and mostly consisted of sentry boxes and gates with simple wings or barriers.

- The Outer Grimmaische Tor (also Kohlgärtnertor; No. 10) was located on the north side of the Old Johannisfriedhof, roughly at the confluence of today's Salomonstrasse with Dresdner Strasse and controlled the road to Dresden via Wurzen and to Eilenburg .

- The hospital gate (No. 11) was on the road to Grimma next to the Old Johannis Hospital , where Talstrasse now meets Prager Strasse. The street name Vor dem Hospitaltore near the Ostplatz still reminds of the hospital gate.

- The Sand Gate (No. 12) was of little importance. It led from what was then Johannisvorstadt into the Johannistal , where there were sand pits - hence the name. The Sand Gate was at the end of Ulrichsgasse (today Seeburgstrasse). Later, a new sand gate was built at the end of Holzgasse (today observatory street ).

- The Windmühlentor (No. 13) stood at the end of Windmühlengasse, now extended as Windmühlenstraße, approximately at the height between the current confluences of Härtel and Emilienstraße. When the gate was dismantled, the owner of the Wachau manor took it to the local park, where it has been preserved to this day. This makes it the only structural remnant of the former Leipzig city gates.

- The Outer Peterstor (sometimes also Zeitzer Tor; No. 14) was at the end of Peterssteinweg, approximately at the height of today's Riemannstraße on the long-distance connection to Nuremberg .

- The Münztor (also raft gate; No. 15) was about the same height, but in the Münzgasse branching off from Peterssteinweg. Since the coin gate did not lead to a long-distance connection, but only to the raft place , it was primarily used to control the import of wood into the city.

- The Outer Ranstädter Tor (also Outer Rannisches Tor or Wassertor; No. 16) was directly behind the bridge of the Ranstädter Steinweg over the Elster , so it was located between the small and the large Funkenburg . This corresponds roughly to the confluence of Thomasiusstrasse with Jahnallee today . The Jahnallee was previously called Frankfurter Straße and continued as a continuation of the Ranstädter Steinweg via Lindenau to Frankfurt am Main .

- The Rosentaltor (No. 17) at the end of Rosentalgasse led to the old Jacobshospital and to Gohlis .

- The Outer Hallische Tor (also Gerbertor; No. 18) was at the end of the Hallische Steinweg, later Gerbergasse, today Gerberstrasse, behind the bridge over the Parthe . It was u. a. intended for traffic to Halle , Delitzsch , Düben , Wittenberg and Dessau .

- The Hintertor (also Schönefelder or Tauchaer Tor; No. 19) was on the way to Schönefeld , Taucha and the Milchinsel , a garden pub popular because of its dairy farming. The gate stood at the end of the back alley, today's Schützenstrasse, roughly before the current junction of Chopinstrasse.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Lutz Rödiger: The Schützenstrasse. A piece of history from Leipzig-East. In: Leipziger Osten , No. 2, Verlag im Wissenschaftszentrum, Leipzig 1994, p. 28, ISBN 3-930433-00-1

- ^ Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse (Leipzig)

- ↑ Picture of the Gothic Gate

- ↑ Picture of the former windmill gate , now in Wachau

literature

- Plan of Leipzig. Verlag der JC Hinrichschen Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1823, ( digitized version )

- Dr. H. Sch .: Of inner and outer gates and gatehouses. In: Leipziger Abendpost from 2/3 January 1937.

- Gertraude Lichtenberger (Ed.): Promenaden bey Leipzig. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig, 1990, ISBN 3-325-00273-0

- Gina Klank, Gernot Griebsch: Lexicon of Leipzig street names. Edited by Leipzig City Archives , Verlag im Wissenschaftszentrum Leipzig, 1995, ISBN 3930433-09-5 .

- Horst Riedel: Stadtlexikon Leipzig from A to Z. PRO LEIPZIG, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-936508-03-8 .

- Wolfram Sturm: History of the Leipziger Post from the beginning to the present. PRO LEIPZIG, Leipzig 2007, ISBN 978-3-936508-28-4 .

- Tobias Kobe: The lost cityscape of Leipzig: The Peterstor. In: Active living in Leipzig. July / August 2011, ed. from the city of Leipzig, p. 44.

- Alberto Schwarz: Das Alte Leipzig - Stadtbild und Architektur , Beucha 2018, ISBN 978-3-86729-226-9 .