GUM department store

The department store GUM ( Russian Торговый Дом ГУМ , transcription Torgowy Dom GUM abbreviated from Главный Универсальный Магазин , Glawny Uniwersalny Magasin to German main department store ) is a former department store and now a shopping center in the Russian capital Moscow . With an area of around 75,000 m² and a history spanning more than 100 years, it is one of the most famous trading companies and, according to the old concept, was the largest department store in Europe.

The GUM building is located in the heart of Moscow on Red Square , opposite the Lenin Mausoleum and the Kremlin . It was built in 1893 based on designs by Alexander Pomerantsev and Vladimir Shukhov as the Upper Trading Ranks (Верхние торговые ряды, Verkhnije torgowyje rjady ) and is now an important monument of historic Russian architecture of the late 19th century. It was closed for decades as a state-owned department store during the Soviet era (Государственный Универсальный Магазин, Gossudarstwenny Uniwersalny Magasin ), the GUM also has a rather eventful history.

General

The GUM department store is located on the west edge of the business district Kitay-Gorod in the Central Administrative District of Moscow, right in the historic core of the city. The building of the department store occupies an almost rectangular area between Red Square, Nikolskaya Street, Wetozhny Street and Ilyinka Street and has ten entrances on all four sides of the building. In the immediate vicinity of the GUM among others, the St. Basil's Cathedral , the Metro -Station Ploshchad Revolyutsii and Moskworezki bridge over the Moscow River .

The 250-meter-long and 88-meter-wide interior of the building houses around 200 separate, differently sized shops on three floors along three glass-roofed longitudinal passages (also known as lines ) and three transverse passages as well as the galleries in the two above them, connected by bridges Upper floor. In terms of functionality, the GUM is therefore no longer a typical department store , but rather a shopping center . Nevertheless, it is still commonly called a department store today, as this name has been firmly established since the Soviet times , when trade was uniformly in state hands. The total sales area of the GUM is around 35,000 m² with a total area of 75,000 m². The average number of visitors is currently around 30,000 customers daily.

The GUM building is owned by the city of Moscow and has been operated since 1990 by Warenhaus GUM , a joint stock company founded in the same year , which has lease rights to the building until 2042. 75 percent of GUM shares are currently held by the Russian fashion house chain Bosco di Ciliegi , the rest is in free float . Until 2005, the company also operated the Stilny Gorod department store chain and some formerly state-owned stores in Moscow in addition to GUM . The operating company's net income in 2006 was approximately $ 27.7 million on sales of $ 97.2 million.

Due to the central location of the house and the resulting high rents for the bars, most of the shops nowadays are aimed primarily at wealthy customers. This applies in particular to the shops in the passages on the ground floor, which are mostly upscale boutiques and specialty stores for expensive branded clothing and shoes, as well as jewelry salons. Several well-known German manufacturers are also represented with their company stores in the GUM, including adidas , Hugo Boss , Puma and Salamander . The third floor of the house is a little cheaper, and in addition to a few mid-range shops, it also houses several restaurants, including a Russian fast food restaurant. In addition, the GUM now houses perfumery, souvenir, toy and household goods stores as well as computer and multimedia stores.

architecture

The GUM building was built between 1890 and 1893 according to a design by the architect Alexander Pomeranzew (1849-1918) with the assistance of the engineer Vladimir Schuchow (1853-1939). Overall, the building is assigned to the so-called neo- Russian or pseudo- Russian style, a historicist style for which a mixture of Russian-traditionalist architecture from the 15th and 16th centuries with neoclassical , Western European elements is typical.

The old Russian influence can be seen above all on the facade of the building, which Pomerantsev designed based on the architecture of the surrounding neighborhoods, including that of the Kremlin and the neighboring History Museum . Typical of this are the large arched windows stylistically based on Russian Orthodox church buildings, the two pointed towers in the central area of the building, which are reminiscent of some of the Kremlin towers, as well as in the style of the Terem Palace and similar elegant residential buildings from the 16th century Roof sections. However, some elements of the European Renaissance can also be seen on the GUM facades , such as the numerous ornaments in the area of the windows and arcade-like portals at the entrances. This, too, is characteristic of Pomeranzew's work, as he lived and practiced in other European countries - including Italy - from 1879 to 1887 and was inspired by the architecture there. About 40 million bricks were used for the entire building when it was erected . The outer walls were clad in granite , marble and limestone . The most elaborate was the facade facing the Red Square, in the middle of which is the central department store entrance: The first floor is clad with marble from Tarussa , which makes the facade appear brighter in its lower area than in the middle and upper area, and with one massive cornice delimited from the two upper floors.

In contrast to the façades, which are primarily linked to the traditions of old Russian architecture, the interior of the GUM was created in a style that was very modern for the end of the 19th century, based on European architecture and provided with numerous steel and glass elements. Unique for the time and still striking today are the transparent, concave roof structures over the three longitudinal passages, each 15 m wide and 250 m long. They were created according to the design of Vladimir Schuchow, who used around 60,000 panes of glass for this, which are supported by metal elements with a total weight of 833 tons. A few years later, Schuchow designed a similar construction for the Kiev train station and a number of other public buildings in Moscow.

The floors of the building were connected by side staircases, which were only supplemented by escalators at the cross passages in the course of the building renovation work in the early 2000s . The galleries on the two upper floors are connected by reinforced concrete bridges, which were built according to a design by the engineer Arthur Loleit (1868–1933) when the department store was built. In the basement of the building there are, among other things, storage rooms and visitor toilets.

Another striking structure inside the GUM is the fountain , which is located in the center of the building, at the intersection of the two central longitudinal and transverse passages. It was installed there a few years after the store opened and originally had a circular basin, which was replaced by an octagonal basin made of red quartzite during the renovation in 1953 . The center of the fountain is a mushroom-shaped bronze construction, the top of which extends to the level of the first floor. The fountain is supported by special metal pillars that are located exactly below it in the basement. Exactly above the center of the building with the fountain, the glass roof construction takes on a dome shape . The fountain still serves as a meeting point for many Muscovites to this day.

history

The upper trading ranks until the 19th century

As can be seen from various documents of the time, the quarters immediately east of Red Square were already characterized by trade before the 17th century. Also on the square itself, which at that time represented the central square of the city, many stalls were set up. In places they reached up to the walls of the Kremlin, which was the tsar's residence until the beginning of the 18th century . As Moscow's population increased in the late 18th century, the street trade in the heart of the city continued to expand; In the second half of the century, the entire area between Red Square and the streets adjoining it to the east looked like a huge market square. The name Obere Handelsreihen (Russian Верхние торговые ряды , Werchnije torgowyje rjady ) had become established for the area immediately adjacent to the Red Square , while the marketplaces of the two quarters east of the Basilius , located on the slope down to the banks of the Moskva River -Cathedral were called Middle or Lower Trade Rows accordingly . Some street names - so the fish alley (russ. Рыбный переулок , Rybnyi pereulok ) or lead crystal alley ( Хрустальный переулок , Chrustalnyi pereulok ) - remember to this day the time when only street trading was operated in the area of Red Square and on certain products - in addition to Fish and lead crystal, for example vegetables, butter, gold, silver or silk - formed their own market rows.

The first efforts to bring the disordered trading activities around Red Square under one roof were made in the second half of the 18th century. In the 1780s, some particularly influential Moscow merchants succeeded in obtaining approval from the Tsar for the construction of a two-story brick building east of Red Square so that it could be relieved of the hustle and bustle of trade, which also obstructed the access to the Kremlin. A few years later , the first forerunner of today's GUM was built with the trading building, which remained unchanged under the name Obere Handelsreihen and united countless stalls behind its facade. At about the same time, the traders had a similar complex built on the middle trading rows. The conception of both houses is attributed to the renowned architect Giacomo Quarenghi , an exiled Italian who designed several buildings, including the Smolny Institute , especially in Saint Petersburg .

However, the newly built trading houses did not last long. Although they were not made of wood, as was customary in Moscow at the time, but rather of brick, they burned down almost completely in 1812 when some city dwellers set large parts of Moscow on fire when French troops approached during the war against Napoleon . After the war, however, trade quickly flourished again and the lines of trade had to be rebuilt. The architect Joseph Bové was commissioned with the reconstruction , who, like his predecessor, had Italian roots and became famous for his decisive role in the reconstruction of Moscow after the great fire in 1812. In the years 1814 to 1815, the Upper Trading Ranks were restored to their old location according to his design in the Empire style and should from now on represent the center of Moscow trade for the next few decades. This second GUM forerunner also essentially consisted of the representative facades, which housed numerous and largely chaotically arranged shop houses inside. How the Upper Trading Ranks must have looked from the outside back then can still be seen relatively well today in the very similarly designed former building of the Middle Trading Ranks, which stands diagonally across from today's GUM on Iljinka Street (location: ▼ ) and is now an exhibition hall is being used. The arcade-like portals, which extend in rows along all four facades of the building, served as entrances to the individual shops behind them in the 19th century.

However, neither the massive construction of the upper trading row nor the reputation of its architect could hide the fact that the building had structural defects just a few years after its completion. More and more often, these led to water penetrating the interior of the house during heavy rainfall and damaging insufficiently covered goods. Since the individual stalls belonged to different owners, it was extremely difficult to coordinate a fundamental renovation of the building. By the middle of the 19th century the rows were in such a bad condition that renovation seemed pointless and the building could only be poorly maintained. The calls for a demolition became louder and louder, so that finally in 1869 the Moscow Governor General also called for a new building.

However, at first it was very difficult to convince the owners of the shops that the demolition was necessary; many of them feared for their existence and initially offered massive resistance to the closure plans. Progress only began in the 1880s, after a respected merchant suggested that a new, three-story building complex should be built in accordance with contemporary architectural standards on the site of the old rows, from whose construction the previous owners would also benefit. Since trading in the heart of Moscow has been a very lucrative affair for a long time, it shouldn't be a problem, according to the plans, to find enough investors, i.e. shareholders, for the construction project. And so on May 10, 1888, a new joint-stock company was founded, which was named the Society of the Upper Ranks on Red Square in Moscow .

From the announcement to the opening

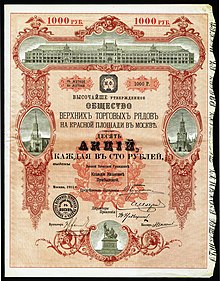

In the first few months after the company was founded, the shares were issued, with a certain part being distributed to the previous owners of the trading ranks according to their respective share in the old building. The remaining shares were available at a unit price of 100 rubles . The sale went extremely well: in the first few days, around ten million rubles were collected. After sufficient capital was available, the company announced on November 15, 1888 an ideas competition for the new trade series. Almost at the same time the old trading house was closed and the demolition work started immediately.

In the invitation to tender, the trading series company attached great importance to fair and neutral competition. In order to prevent collusion, preferential treatment and similar occurrences, the competition was conducted anonymously; the names of the participating architects remained strictly confidential until the results were announced and were not accessible to the jury. A total of 23 designs were submitted. After their assessment by the jury, the jury announced its decision on February 21, 1889: The first prize, endowed with 6000 rubles, went to the design submitted by Alexander Pomerantsev and Vladimir Schuchow . Pomerantsev was an architecture professor at the St. Petersburg Academy of Art and was therefore already a well-respected person in Russian architecture circles, while the young engineer Shukhov was still completely unknown at the time - his most famous buildings, such as the Moscow radio tower , were not built until decades later. The experts praised the Pomeranzews and Shukhov project as, literally, “rational and economical” and at the same time architecturally harmonizing very well with the old Russian ensemble around the Moscow Kremlin. The merchants involved in the company particularly liked the design by Wladimir Schuchow's glass roofing over the passages, which stylistically linked to similar shopping passages in European metropolises such as Milan , Paris and Vienna , which were just in fashion at the time . Such a construction was completely unknown in Russia until then.

The three award-winning designs finally went to St. Petersburg for assessment by Tsar Alexander III . He praised the jury's decision and then issued the building permit for the new retail series. The laying of the foundation stone, which was attended by almost all of Moscow's VIPs, including the Governor General, took place on May 21, 1890. Pomerantsev had already calculated the cost and duration of the construction work precisely in his draft. A commission set up especially for this purpose monitored the construction work throughout its three-year course, in particular compliance with the specified time and budget as well as the structural properties of the building being created and the quality of the building materials used, which were supplied by well-known Russian manufacturers. Great importance was also attached to the quality of the workforce: when recruiting craftsmen from other regions of the Russian Empire , the reputation of the respective profession in the region was always taken into account. The Moscow public, however, followed the construction work closely; the newspapers reported on the construction almost every day, and even in other European countries the Moscow construction site, with its enormous dimensions, was mentioned in the print media. Around two years after the start of construction, the building was finished except for the interior fittings and could be entered and viewed by its shareholders. In the fall of 1893, the trading lines were finally completed and inaugurated on December 2nd of the same year with a solemn ceremony.

The heyday

The opening of the new trading house in the heart of Moscow was a major event that also met with resonance beyond the borders of the Russian Empire. In addition to the new type of glass roof, through which a lot of daylight penetrated into the interior of the building, the new retail series had a very modern interior design for the time, including central heating , several electrically operated freight elevators - also an absolute novelty at the time - and even included an in-house power plant for power supply in the basement. After sunset, around 7,000 electric light bulbs lit the passages.

Within a few days the Upper Ranks became a crowd puller and a tourist attraction in Moscow, which at that time already had almost a million inhabitants. Even those who couldn't afford to go shopping there came to see the new superlative department store. The passages on the ground floor were like a covered promenade where it was warm in summer even in winter.

Above all, wealthy citizens got their money's worth here. The range of products offered by the originally almost 350 shops, which were spread over four levels including the basement, ranged from sweets and delicatessen products to various domestic and foreign perfumery products, fashion items, furs, wristwatches and fine jewelry to furniture and sanitary technology. For the first time in Russia, price tags were used in the retail series, thus initiating the transition to a completely new commercial culture, which stood out from the haggling in street retail and smaller shops that had been common up until then . The most well-known Russian and foreign producers presented their goods here and offered them for sale with a lot of advertising expenditure, which ultimately paid off despite extremely high rents for the shops (especially those on the ground floor). In addition to almost all kinds of goods, the retail chain's customers were able to fall back on a wide range of accompanying services, including porters for the transport of purchased goods, several restaurants, a bank branch, a post office, a hairdressing salon and even a dental practice. The upper floor of the department store also housed an event hall in which concerts and art exhibitions were occasionally held.

For more than twenty years, from its opening to the end of the tsarist empire, the upper trading ranks were the center of Moscow's economic and social life and were considered one of the best department stores in the world due to their extensive, high-quality range and exemplary service for the time. Because of this, they attracted millions of visitors from Russia and abroad.

After the revolution

A few months after the October Revolution of 1917 and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks , the new rulers began to nationalize the upper trading ranks . The shops in the building closed one after the other, because even for smaller shopkeepers, who were initially spared the expropriation, trading in the increasingly empty rows was no longer worthwhile. The state authorities used a large number of vacant shops as premises for newly formed ministries and other state institutions; Thus a formerly elegant perfume shop became the seat of the People's Commissariat for Food Distribution.

In 1921, trade in the upper ranks, which had come to a standstill by then, revived for a few years when the New Economic Policy initiated by Lenin allowed privately operated trade. At the same time, the department store was given its current name GUM , which at that time and during the entire period of socialism stood for Gosudarstwenny Uniwersalny Magasin ( Государственный Универсальный Магазин ), i.e. state department store . In addition, the GUM range in the 1920s was nowhere near as extensive and elegant as it was before the revolution; it was essentially limited to everyday objects and propaganda needs such as red flags or portraits of Soviet statesmen.

With the end of the New Economic Policy in the early 1930s, however, trading in the GUM was finally over. The shops were cleared and occupied by a number of other state organizations; For this purpose, many former shops were rebuilt and merged to create larger rooms. In the 1930s, a canteen, a print shop and even several communal apartments (so-called communal kas ) were built in the building, with the latter surviving there until the 1960s. The building kept the name GUM during this period, even though it was officially no longer a department store.

Largely spared the German bombing of Moscow in World War II , the GUM was still threatened with demolition for a number of years in the late 1940s after leading Soviet architects of the time commissioned Stalin to design a giant sculpture to commemorate the victory over Germany had worked out. Since this was to be located in the heart of the capital, i.e. on Red Square, but the square itself was to remain free for military parades and solemn demonstrations, this plan included the final closure and demolition of the department store. Shortly after Stalin's death in 1953, however, not only was the demolition plan rejected, but the Council of Ministers of the USSR also decided to reopen the GUM as a department store. According to oral tradition, this happened on the initiative of the party functionary and later head of state Nikita Khrushchev , who wanted to revive the GUM as a model department store. The renovation of the building and the reconstruction of the interior began immediately, during which, among other things, a large number of smaller shop cells were merged into large halls. The renovation work proceeded very quickly, so that the reopening of the house could take place on December 24, 1953.

From the reopening until today

From the reopening until the collapse of the Soviet Union , the GUM retained its reputation as the country’s flagship warehouse. While the shortage of goods typical of socialist states until the early 1990s ensured that ordinary shops, department stores and department stores of the Soviet empire only had an extremely poor range of consumer goods, at the same time there was no secret one in the GUM that was not available to the public Accessible department in which high-ranking civil servants and their relatives could stock up on high-quality clothing, some of which were imported from the West, and other so-called deficit goods. Excess stocks kept coming back to the generally accessible departments, to the delight of ordinary consumers. This in turn meant that every morning, hours before the opening, long queues formed in front of the GUM entrances, as many ordinary citizens - often specially traveled from other cities in the Soviet Union - hoped to get hold of one or the other in short supply . The fact that such scenes took place in the very heart of the Soviet capital, right across from the Kremlin and the Lenin mausoleum, was a thorn in the side of conservative statesmen in particular, and in the late 1970s even led to plans to close and tear them down again Department store. According to a modern legend , the GUM owes its existence at that time only to the personal interference of the head of state Leonid Brezhnev , whose wife Viktoria was a regular customer of a tailor shop there.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent privatization of state property in Russia ushered in new times for the GUM. As early as December 1990, at the time of perestroika , the operator-stock corporation Warenhaus GUM was founded . The former state-operated sales area of the department store was gradually rented to various private retail companies. The name has been adapted to the new circumstances: The old, familiar abbreviation GUM remained, but since 1990 it has stood for Glawny Uniwersalny Magasin (Russian Главный Универсальный Магазин ), i.e. the main department store instead of the previously state department store . In June 1993, the now privatized department store celebrated its 100th anniversary with a festival lasting several days and a celebratory parade on Red Square in the style of the late 19th century. A little later, the central GUM entrance from Red Square was reopened after around 40 years. During the Soviet era, it was closed to the public, as the state authorities wanted to prevent the crush and queues from forming directly on Red Square and worsening the image of the Soviet state in the eyes of foreign tourists.

In the following decade, the GUM developed from a formerly socialist department store to an upscale shopping mall. The building itself was also extensively renovated from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s, and its interior was renewed. In addition to the installation of escalators and lifts for the disabled, as well as the renovation of the fountain, shopping malls were created on the second floor, which was previously used exclusively for office space. It is also planned to convert the basement floor for its future use as a sales area.

The GUM in art

In 1963, the GUM department store was one of the locations and locations of the famous Soviet film Zwischenlandung in Moscow (also: I walk through Moscow , Russian Я шагаю по Москве ) with the then 18-year-old Nikita Michalkow . In one scene there, as a young worker Kolja, he and his friend Sascha, who is about to get married, choose a new jacket for him. The GUM is also mentioned in a song by the famous Soviet poet Vladimir Vysotsky : A kolkhoz farmer who is on a business trip in Moscow writes to his wife in the village that he is now going to the GUM - " it's like our barn, only with glass " - to buy a dress for her, " ... because you can get too boring for me with your sheepskin and the gray dress with faded patterns ".

Movie

- The big dream department stores - GUM, Moscow. Documentary film, Germany, 2017, 52:30 min., Script and director: Inga Wolfram , production: Telekult, rbb , arte , series: Die Große Traumkaufhäuser , first broadcast: June 11, 2017 on arte, summary by ARD , with many archive recordings.

literature

- Rainer Graefe: Vladimir G. Šuchov 1853–1939. The art of economical construction . DVA, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-421-02984-9 , p. 154.

- William Craft Brumfield: The Origins of Modernism in Russian Architecture . University of California Press, Berkeley 1991, ISBN 0-585-32903-6 , pp. 20-28.

- Polina Efimovych: Torgovyj dom GUM: Vekovaja istorija ( Memento of September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). In: Portfelnyj Investor, No. 1/2007, pp. 42–46.

- Irina Paltusova: Krupnejšij passaž Rossii . In: Mir Muzeja , No. 6/1993 , ISSN 0869-8171 , pp. 14-20.

- Anatoli Rubinow: Istorija trëch moskovskich magazinov. Magazine na Krasnoj ploščadi . Nowoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, Moscow 2007, ISBN 5-86793-519-1 , pp. 103–243.

Web links

- GUM.ru - Official site (Russian, Chinese, English)

- GUM department store in the enc.ex.ru online lexicon ( Memento from December 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (Russian)

German pages about the GUM

- GUM department store in Moscow. In: poezdka.de

- GUM department store. In: Structurae

- A piece of Russian history. The GUM in Moscow. In: arte , June 11, 2017.

Pictures, videos

- Photo gallery on Russia current

- Video: About the roof structures of the GUM by Vladimir Schuchow

Individual evidence

- ↑ Efimovych 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ Skrin.ru: GUM Department Store Joint Stock Company , report dated June 1, 2007; last accessed on October 25, 2007 (inactive)

- ↑ Meeting point at the fountain. ( Memento from September 6, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ). In: GUM , with many photos, (Russian).

- ↑ Site plan of the fountain. In: GUM .

- ^ Inga Wolfram : The great dream department stores - GUM, Moscow. In: arte / ARD , June 11, 2017.

- ^ History of the Red Square. In: 7ya.ru , Russian, accessed June 11, 2017.

- ↑ krealist.ru: GUM department store. (Russian) ( Memento from August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Irina Šanina: This well-known GUM - what's new? ( Memento of September 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). In: rol.ru , June 6, 2003 (Russian)

- ↑ Rubinow 2007, p. 205.

- ↑ Anatoli Rubinov: GUM in the Soviet Union. ( Memento of September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). In: Novaya Gazeta , October 26, 2000.

Coordinates: 55 ° 45 ′ 17 ″ N , 37 ° 37 ′ 17 ″ E