History of Latvia

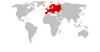

The history of Latvia is the history of a historical landscape in which there was no separate state until the end of the First World War . It includes in particular the times during the Teutonic Order and the Russian Empire , the first independent Latvian state after the declaration of independence in 1918 up to the establishment of the so-called Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic as part of the Soviet Union as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact , the German occupation during the World War II , the Cold War period and the regaining of independence in 1990.

Prehistory and early history

The prehistory of Latvia is usually divided into the Stone Age , Bronze Age, and Iron Age and lasted until the 12th century AD.

About 14,000 years before our era, at the end of the last Ice Age , today's moraine landscape of the Baltic was formed. In the wake of hunted animals appeared around 9000 BC. The first people whose ethnicity nothing is known.

From the 3rd millennium BC Finnugian tribes immigrated to this area from the north and northeast . They were made in the 2nd millennium BC. Partially ousted or assimilated by Indo-European tribes . These forerunners of the later Latvians and Lithuanians lived from agriculture and livestock farming. In ancient scriptures the Balts are referred to as Aisti or Aesti and the entire country as "Estonia". The Anglo-Saxon traveler Wulfstan still used this word in its ancient meaning in the 9th century.

The Balts lived under local princes, but did not have a unified state, which meant a military weakness and already in the Vendel period attracted first Scandinavian , Kievan , and later Polish and German interests.

For example, Curonian weapons and pieces of jewelry from the 10th century (decorative needles, fibulae and swords) were found on the Gotland coast. A woman's grave in Hugleifs contained typical Curonian jewelry. The grave documents the presence of cures on the island. The same decorative needles and swords can also be found in large numbers in the vicinity of today's Klaipėda and Kretinga . The finds on Gotland and Öland as well as in the central Swedish Uppland indicate trade relations with the Baltic as early as the 10th and 11th centuries.

The German Order

The defeat of the Brotherhood of the Sword in the Battle of Schaulen (Lithuanian Šiauliai) against Lithuania in 1236 led to the takeover of Latvia by the Teutonic Order in the following year and to the annexation of Livonia to the Order (see Livonian Order ). Some parts of the country remained in the hands of the Bishop of Riga or the city of Riga .

With the subjugation of the tribes of the Livs , Kurds and Semigalls by the Teutonic Order, German immigrants came to Livonia. For centuries, the German upper class provided the urban bourgeoisie and the large landowners.

The Hanseatic League

In the Middle Ages, the Livonian cities, above all Riga , were linked to the Hanseatic League in the Livonian confederation and were shaped economically by the trade connections, especially with the German port cities, the Netherlands and Flanders , Scandinavia and Russia .

The Reformation

As a result of the Reformation , the religious state became a duchy and Livonia became Lutheran . The Livonian War lasted from 1558 to 1583. As part of the religious state, Livonia was divided by the Union of Vilnius (November 28, 1561) after the end of the Livonian-Lithuanian War . Estonian parts of the country went to Sweden, some smaller areas fell to Denmark or came under Polish sovereignty . Kurland was led as a hereditary duchy by the last Teutonic order master, Duke Gotthard Kettler, under Polish rule, the remaining part came to the unified Poland-Lithuania . After a short period of independence, Riga, like some of the Danish possessions, also became part of Poland.

Sweden, Poland and Russia

In 1629 Sweden conquered Livonia . Courland remained an independent duchy under Polish sovereignty ( Duchy of Courland and Semigallia ). The southeastern part of Livonia around Daugavpils also remained Polish ( Polish-Livonia ). The Great Northern War from 1700 to 1721 brought another change of rule. With the Peace of Nystad (1721), Livonia and Estonia became Russian provinces. With the third partition of Poland in 1795, Courland and Polish-Livonia ( Latgale ) also came to Russia. Courland and Livonia , together with Estonia, formed the Baltic Sea Governments , which had a certain special position: they were influenced by German upper classes and were Lutheran ; urban self-government was more pronounced.

The establishment of the Republic of Latvia in 1918 and the interwar period

An awakening national feeling among the Latvians , dominated by Russia and the German upper class, led to independence movements. In 1917 areas in the Baltic States were restructured: Livonia ceded its Estonian part to Estonia, but was annexed to Courland in the south . After the German occupation at the end of the First World War, the Latvian People's Council, which had met the day before, declared the independence of Latvia on November 18, 1918 . The Latvian War of Independence followed (until 1920). The Red Latvian Riflemen could not enforce the claim of Soviet Russia and the first Latvian Soviet Republic against Latvia, which was supported by the Estonians and the Baltic Germans ( Baltic State Armed Forces , Iron Division ) and had to withdraw from the Baltic States. A failed coup attempt by the German-Baltic minority was followed by a Latvian government, which on August 11, 1920 was recognized by Soviet Russia in the Rīga Peace Treaty . Latvia also granted Latgale the demarcation of the language border in this treaty .

On June 15, 1921, the Parliament passed a resolution on the flag and coat of arms of Latvia . These insignia were used by all state institutions from that day on. As of June 15, 1921, independent Latvia had diplomatic missions in many European countries as well as in China and the USA. On November 7, 1922, the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia came into force. As early as December 1919, the minorities living in the country (Russians, Germans, Jews and others) had extensive rights secured by law. a. own schools and their self-administration.

In the 1920s, Latvia experienced an economic and cultural boom. In 1922 alone, 300 municipal libraries were opened. In terms of the number of books published (in relation to the number of inhabitants), Latvia was in second place in Europe after Iceland.

A coup d'état on May 15, 1934 ended the parliamentary government. From then on, Kārlis Ulmanis ruled the state authoritarian.

The de facto end of independence in 1939/1940

During the period up to World War II, Latvia came under increasing pressure from the Soviet Union and Germany. On June 7, 1939, in Berlin, a non-aggression treaty was signed between Germany and Latvia. In a secret additional protocol to the German-Soviet non-aggression pact on August 23, 1939, however, the two great powers agreed that Latvia was part of the Soviet Union's sphere of influence .

The Soviet Union imposed a support and base agreement on Latvia , which the Latvian Foreign Minister Vilhelms Munters had to sign on October 5, 1939. On October 31, 1939, a resettlement agreement was signed between the German Reich and Latvia. The resettlements were carried out immediately: 48,600 Baltic Germans were resettled to Germany. This so-called repatriation was declared complete on December 15, 1939. Under threat of violence, Latvia had to agree to the stationing of further Soviet troops in June 1940, which occupied Latvia on June 17, 1940.

A pro-Soviet government was set up and requested to be incorporated into the Soviet Union. Most Western states did not recognize Latvia de jure as part of the Soviet Union, but the vast majority of them did de facto .

Around 35,000 Latvians were deported to Siberia from 1940 to 1941 , 15,000 of them in the night of June 13-14, 1941 alone. A third of the Latvians deported that night were Jews. Ivan Serov , General of the NKVD , had already signed the secret orders for the deportation of the Latvians on October 11, 1939, six days after the Soviet-Latvian "assistance agreement". The remnants of the German minority, which had formed the country's educated class for centuries, were resettled.

The German occupation 1941–1945 and the Holocaust in Latvia

From July 10, 1941 to 1945, Latvia was occupied by the Wehrmacht . As the general district of Latvia, it was placed under German civil administration, which was subordinate to the Reichskommissariat Ostland , from July 25, 1941 to the Daugava (excluding Riga) and from September 1, 1941 to the north-east of it. This civil administration was manned by a few people, who after the year of the Stalinist reign of terror had it easy to present themselves as liberators and to build up a collaborating Latvian self-government from so-called shop stewards.

Latvian SS units made up of volunteers , and later forcibly recruited soldiers, fought on the German side against the Soviet Union in World War II. Local collaborators were involved in all areas of the Holocaust initiated by the occupiers , from shooting to the registration and confiscation of Jewish property. During the German occupation, extermination actions against Jews took place by the German occupying power, which led to the almost complete annihilation of the Jewish population of Latvia . The Latvian auxiliary police and a Latvian special command under Viktors Arājs , which was subordinate to the SD and carried out some of the mass shootings, were important instruments .

On January 2, 1942, the town of Audriņi was razed to the ground by German security forces and 205 residents shot in a nearby forest. 30 men from Audrini were shot publicly in Rēzekne on January 4, 1942 . The reason for the massacre was the alleged support of Soviet soldiers and partisans. At times there were Jewish ghettos in the cities of Riga, Daugavpils and Liepāja . Notorious places of mass murder were Rumbula , the Bickern Forest (Biķernieki) and Šķēde (north of Liepāja).

The second occupation of Latvia by the Soviet Union in 1944/1945

Until May 8, 1945, German troops, including about 14,000 soldiers of the 19th SS Division , held the "Fortress Kurland" , where an independent Republic of Latvia had been proclaimed under German occupation in March 1945. After the Red Army had crossed the national border in June 1944 and had brought the entire country under control by May 1945, around 57,000 residents were drafted into the Red Army, mainly in the 130th Latvian Rifle Corps . In addition, the deportation, imprisonment and killing of Latvians - especially from the upper and middle classes and collaborators - by the Soviet occupying forces began again. Around 200,000 refugees had reached Germany and around 5,000 to Sweden before the end of the war . Most of them later moved to the USA and Australia . Various exile communities sprang up in these countries . Until 1953 there were nests of resistance in the Baltic States of the " forest brothers ", loose groups of anti-communist underground fighters who officially laid down their arms only in 1953 after the death of Josef Stalin and a political amnesty.

Latvian SSR 1945–1990

In the post-war period, the so-called Latvian SSR was renewed, which according to Soviet historiography had existed since 1940. Latvia's membership of the Soviet Union, which is illegal under international law, was not called into question by the allies in the agreements on the post-war order (Tehran and Yalta conferences in 1943 and 1945) and when the UN was founded . From the perspective of the Western powers, the Baltic states were not an issue for whose sake they were prepared to enter into a confrontation with the Eastern war allies. However, the most important western states, especially the USA , Great Britain , France and also the Federal Republic , later pursued the policy of non-recognition of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states.

As a result, measures by the Soviet central government threatened to turn the Latvian population into a minority in their own country. The first large wave of mass deportations in 1941, already mentioned, was followed by two even larger ones in 1945 and in March 1949 . Mostly Latvian farmers were affected, mostly women and children, who were forcibly resettled in various areas of Siberia. According to recent calculations, between 1940 and 1953 around 140,000 to 190,000 Latvian citizens were deported or imprisoned by the Soviet power. Citizens from other regions of the USSR, on the other hand, poured into Latvia, where they took on leading positions.

Those who survived the slave-like working conditions in Siberia were only allowed to return after Stalin's death in 1956. However, it was forbidden to talk about the injustice that had occurred, so that it could only come to terms with the political changes from 1987 onwards.

Agriculture was collectivized . Latvian industry was nationalized and organized in combines . New factories were built especially in and around Riga, the majority of whose workforce came from other Union republics , in particular from the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic . The forced industrialization also served the Russification . In 1935 there were 77% Latvians, 8.8% Russians, around 5% Jews, around 4% Germans, 2.5% Poles, 1.4% Belarusians and 0.1% Ukrainians living in Latvia. By contrast, in 1989 there were only 52% Latvians, but 34% Russians, 4.5% Belarusians, 3.5% Ukrainians, 2.3% Poles and 1.3% Lithuanians.

The small Latvian SSR always had to subsidize the large Soviet Union. The documents on the financial flows between the Gosbank headquarters in Moscow and its branch in Riga show that the Latvian SSR was consistently a net payer .

Restoration of independence in 1990

On July 28, 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR passed a declaration according to which Latvia had lost its sovereignty due to "the criminal Stalinist foreign policy of 1939/1940". Henceforth, the statement said, laws passed in Latvia would take precedence over those of the Soviet Union - an affront to Mikhail Gorbachev's efforts to hold the USSR together.

On March 18, 1990, the citizens of Latvia elected a Supreme Soviet for the last time, which constituted itself as the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia , i.e. as a provisional parliament. On May 4, 1990, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia declared the country's independence to be restored. This process, which was preceded by the so-called Singing Revolution , was recognized by the Soviet Union on September 6, 1991, together with the independence of Lithuania and Estonia .

Initially, Latvia was considered politically and economically unstable. The country set itself the task of reconciling the national identity of Latvia with the Latvian identity (the identity of the ethnic Latvians) and the identity of the non-Latvian ethnic groups in Latvia, which was attempted through a special integration and minority policy. At the same time the political and economic system had from communism to Western democracy and a market economy transformed to be. In the course of the 1990s, the economy experienced an upswing.

On September 20, 2003, 67% of Latvians voted in a referendum for their country's accession to the EU on May 1, 2004 , 32% voted against and 0.7% abstained with a turnout of 72.5%. On March 29, 2004, Latvia also became a member of NATO . Latvia has been part of the European Monetary Union since January 1, 2014 , with the euro replacing the lats .

See also

literature

- Alfred Bilmanis: Latvija's career: From the bishopric of Terra Mariana to the free people's republic. A handbook on Latvia's past and present. 4th edition, Lamey, Leipzig 1934.

- Hans von Rimscha : Latvia's becoming a state and the Baltic Germans . Plates, Riga 1939.

- Sonja Birli : Latvia, Latvians. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 18, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016950-9 , pp. 277-281.

- Ilgvars Butulis, Antonijs Zunda: Latvijas Vēsture . Jumava, Riga 2010, ISBN 978-9984-38-827-4 .

- Susanne Nies: Latvia in international politics. Aspects of his foreign policy (1918–95) . Lit, Münster 1995, ISBN 3-8258-2624-4 .

- Katrin Reichelt: Collaboration and Holocaust in Latvia 1941–1945. In: Wolf Kaiser (ed.): Perpetrators in the war of extermination. The attack on the Soviet Union and the genocide of the Jews . Berlin / Munich 2002, ISBN 3-549-07161-2 , pp. 110-124.

- Ralph Tuchtenhagen : History of the Baltic countries. 3rd, updated edition, CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-50855-4 .

Web links

- History of Latvia . The Latvian Institute

- Declaration of the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR on the restoration of the independence of the Republic of Latvia (May 4, 1990)

Historical maps

From the Atlas To Freeman's Historical Geography, Edited by JB Bury, Longmans Green and Co. Third Edition 1903 from the University of Texas (Austin):

- Baltic Lands 1000 AD (332K)

- Baltic Lands 1220 AD (323K)

- Baltic Lands 1270 AD (332K)

- Baltic Lands 1350-1360 AD (383K)

- Baltic Lands 1400 AD (366K)

- Baltic Lands 1478 AD (434K)

- Baltic Lands 1563 AD (332K)

- Baltic Lands 1617 AD (332K)

- Baltic Lands 1701 AD (417K)

- Baltic Lands 1772 AD (366K)

- Baltic Lands 1795 AD (357K)

- Baltic Lands 1809 AD (374K)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ilgvars Butulis, Antonijs Zunda: Latvijas vēsture. Riga 2010, ISBN 978-9984-38-827-4 , p. 13.

- ^ Karl Bosl : Europe in the Middle Ages. World history of a millennium. Carl Ueberreuter Verlag, Vienna 1970, p. 274.

- ↑ Adolfs Silde: Development of the Republic of Latvia. In: Boris Meissner (Ed.): The Baltic Nations: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania . Markus-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-87511-041-2 , pp. 63–74, here p. 64.

- ↑ Adolfs Silde: Development of the Republic of Latvia. In: Boris Meissner (Ed.): The Baltic Nations: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania . Markus-Verlag, Cologne 1990, p. 66.

- ↑ a b Adolfs Silde: Development of the Republic of Latvia. In: Boris Meissner (Ed.): The Baltic Nations: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania . Markus-Verlag, Cologne 1990, p. 68.

- ↑ Adolfs Silde: Development of the Republic of Latvia. In: Boris Meissner (Ed.): The Baltic Nations: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania . Markus-Verlag, Cologne 1990, p. 71.

- ^ Arveds Schwabe: Histoire du peuple letton . Bureau d'Information de la Légation de Lettonie à Londres, Stockholm 1953, p. 223.

- ↑ Peter Van Elsuwege: From Soviet Republics to EU Member States: A Legal and Political Assessment of the Baltic States' accession to the EU. Leiden 2008, ISBN 978-90-04-16945-6 , p. 34 f.

- ^ Ansgar Graw : The fight for freedom in the Baltic States . Straube, Erlangen 1991, ISBN 3-927491-39-X , p. 127.

- ↑ Latvia. In: Eberhard Jäckel (Ed.): Enzyklopädie des Holocaust. The persecution and murder of the European Jews. Volume 2: HR . Argon, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-87024-302-3 , pp. 854-857, here p. 856.

- ↑ Valdis O. Lumans: Latvia in World War II . Fordham University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8232-2627-1 , p. 135.

- ↑ "We only had the SS - and the Red Army". In: Welt Online. Retrieved May 16, 2015 (Edgars, then a teenager, cannot describe exactly how he experienced the start of the war, what he felt. The war started here in the summer of 1940. He was on his way to school when he saw the first Soviet tank . “The neighbor is coming with the tank, what can be happy about that?” But the Skreijas were lucky. Nobody was deported, nobody was arrested. The family was able to continue to operate almost as before, even if they turned from Latvian to Soviet citizens overnight […] It was again in the summer of '41, when Wehrmacht tanks rolled through the streets. Edgars beamed: "A beautiful, happy, bright day. For the Latvians." Flowers, flags, songs on the streets Did he see the Germans as liberators? “Definitely! As liberators from this murderous government.” The Soviets had left bad memories behind. They had deported tens of thousands of Latvians to Siberia in the dark and fog and installed a puppet government.).

- ↑ Inesis Feldmanis, Kārlis Kangeris: The Volunteer SS Legion in Latvia. ( Memento of June 5, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Latvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2004.

- ^ Katrin Reichelt: Collaboration and Holocaust in Latvia 1941–1945. In: Wolf Kaiser: perpetrators in the war of extermination. The attack on the Soviet Union and the genocide of the Jews. Berlin / Munich 2002, p. 115.

- ↑ a b Ilgvars Butulis, Antonijs Zunda: Latvijas vēsture. Riga 2010, ISBN 978-9984-38-827-4 , p. 148.

- ↑ Peter Van Elsuwege: From Soviet Republics to EU Member States: A Legal and Political Assessment of the Baltic States' accession to the EU . BRILL, 2008, ISBN 90-04-16945-8 ( google.com [accessed August 12, 2016]).

- ↑ Michele Knodt, Sigita Urdze: The political systems of the Baltic states: An introduction . Springer-Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-19556-8 ( google.com [accessed on August 12, 2016]).

- ↑ Michele Knodt, Sigita Urdze: The political systems of the Baltic states: An introduction . Springer, 2012 ( google.com [accessed August 12, 2016]).

- ↑ Daina Bleiere, Ilgvars Butulis, Antonijs Zunda, Aivars stranga, Inesis Feldmanis: Latvijas vēsture: 20 gadsimts. Jumava, Rīga 2005, ISBN 9984-05-865-4 , p. 304.

- ↑ Rasma Karklins Silde-: forms of resistance in the Baltics 1940-1968. In: Theodor Ebert (Ed.): Civil resistance. Case studies on nonviolent, direct action from domestic peace and conflict research . Bertelsmann Universitätsverlag, Düsseldorf 1970, ISBN 3-571-09256-2 , pp. 208-234.

- ↑ Rudolf Hermann: The Baltic States want justice. Compensation demands on Moscow in the billions. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of December 14, 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Florian Anton: Statehood and Democratization in Latvia. Development - Status - Perspectives . Ergon-Verlag, Würzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-89913-702-6 , p. 181.

- ↑ Julija Perlova: Constructions of Identity in the Media Using the Example of Latvia. A frame analysis of the 2004 and 2009 European elections. (PDF; 891 kB) 2010, p. 16 f.

- ↑ Toms Ancitis: Naturalization for Free ? In Latvia the status of non-citizens is being debated again after a signature campaign . New Germany , September 19, 2012.

- ↑ RIA Novosti archive, image # 631781 / V. Borisenko (CC-BY-SA 3.0)