Lousberg

| Lousberg | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Overlooking the Lousberg by Lauren Berg from |

||

| height | 264 m above sea level NHN | |

| location | Aachen , North Rhine-Westphalia , Germany | |

| Coordinates | 50 ° 47 '13 " N , 6 ° 4' 45" E | |

|

|

||

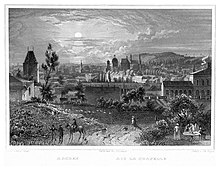

The Lousberg is with 264 meters height, a striking elevation on the northern edge of the historic center of the city of Aachen , at the beginning of the 19th century, designed by Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe as forest and mountain park was designed. The origin of the name is not entirely clear. It could come from lousen (“to look, to look”), since the mountain offers an excellent all-round view, or it could go back to Ludwig the Pious (Louis), the son of Charlemagne . Another explanatory approach refers to the expression lous in the Aachen dialect for "smart".

Geology, formation

From a geological point of view, the Lousberg is one of the three witness mountains of Aachen, alongside the Salvatorberg and the Wingertsberg, and one of the southernmost branches of the Aachen - Limburg chalk board . It originated during the Upper Cretaceous , in which the region around Aachen was hit by a Europe-wide sea advance in which initially sandy, later predominantly calcareous sediments were deposited ( Aachen chalk ). The morphological elevation of the Lousberg is related to tectonic movements that led to the formation of the Lower Rhine Bay .

At the base of the Lousberg, dark gray, clayey to sandy sediments of the so-called Hergenrath strata were deposited, which formed in a swampy river delta . In these layers, silicified wood, charcoal and numerous concretions made of marcasite are embedded in places . Due to the water-retaining properties of the deposits, the clay of the Hergenrath layers both on the Lousberg and in the Aachen Forest is the most important source horizon in the region.

Subsequently, in the course of the Upper Cretaceous the area was gradually flooded by the sea and 30–50 m thick quartz sands of the Aachen Formation were deposited, which were mined in small sand pits on the lower slope of the Lousberg (e.g. at today's playground at the end of the Kupferstrasse). There is a clear erosion discordance between the sands of the Aachen and the younger Vaals formation of the Campanium . The sands of the Vaals Formation are characterized by the increased occurrence of glauconite . Due to its greenish- brown weathering color , these layers were formerly known as Vaals green sand .

In the Campanian tectonic movements began to increase, which are related to the sinking of the Lower Rhine Bay and led to the uplift of the Lousberg plaice. Vijlener and Orsbacher Kalk were probably not primarily sedimented due to their high altitude.

It was not until the Maastrichtian period that the Lousberg plaice was flooded again when the sea level rose. Dead microorganisms were deposited in a lime sludge that today forms the so-called Vetschauer Kalk . The original thickness of the limestone layer on the Lousberg was approx. 6 m. The top 4.5 m contained minable, brown flint deposits that were the subject of Neolithic mining. The flints were completely dismantled with the exception of a small residue and the limestone material that was not required was disposed of on the surrounding slopes. Due to the low level of solidification of this rubble material, small landslides occur again and again today , as can be seen from the hooking of many trees and in cracks in the footpaths.

fauna and Flora

From an ornithological point of view, the Lousberg has a high level of species diversity, as recorded by RWTH Aachen University . The population of bats, amphibians and reptiles is also remarkable. The amphibians find spawning waters in the Soers north of the Lousberg. There is a coherent yew grove on the high plateau . There are extensive stocks of wild daffodils in the former St. Raphael Monastery Park, the listed Müschpark , located to the north .

history

During the Neolithic Age (the Neolithic ), flint was intensively mined on the Lousberg around 5,500 to 5,000 years ago. From this gray flint, which can be easily recognized by its characteristic chocolate-brown color zones, only axes were made on site, which were brought to the settlements as semi-finished products and were only ground there.

Due to its striking color, Lousberg-Feuerstein is an ideal object for research on the dissemination of ax blades. From the 14 C data of the artifacts found in the Lousberger overburden, the mine ran for between 3500 BC. BC and 3000 BC From calculations, which put the volume of the overburden, the weight of the production waste and the average weight of ax blades in relation, there is a figure of around 300,000 blanks that have left the Lousberg. These axes have been passed on to Belgium (Thieusies, approx. 160 km as the crow flies), Central Hesse ( Büdingen , approx. 225 km as the crow flies) and East Westphalia ( Neuenknick near Minden , approx. 280 km as the crow flies).

The Stone Age quarrying of the flint almost completely reconditioned the central plateau of the Lousberg, which originally consisted of a 6 m thick chalk-lime cover. The overburden piles of the flint mine, which are still up to 4.5 m thick, can still be recognized today as a hilly landscape under the yew forest. Flint fragments were found on the surface and on the steep slopes.

During the period of Roman settlement, the limestone was used to build the Aachen thermal baths , and in the Middle Ages to build the Barbarossa Wall.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Napoleonic geographer Jean Joseph Tranchot began with the topographical survey of the Rhineland on a scale of 1: 20,000, starting from a triangulation point on the Lousberg. On 17 October 1807, the French Ministry of War in honor Tranchots and his staff built a obelisks from Blaustein designed by the Ingenieurgeografen Capitaine Boucher. The obelisk is a precisely measured central point that used to be the starting point for astronomical observations and for mapping in the region. From there, further points in the area were determined using the triangulation method, with the help of which the entire area could ultimately be mapped. With the deposition of Napoleon on April 2nd, 1814, the monument was destroyed. On May 15, 1815, the obelisk was rebuilt by order of the Prussian baron Karl von Müffling , who continued the surveying work on behalf of the Kingdom of Prussia . The inscription with an eulogy for Napoleon was replaced by the inscription that is still legible today. The damage to the edges of the stone has been compensated for by chamfers that are atypical for an obelisk .

At this time, the first landscape park in Europe initiated by citizens (and not by princes) was created on the Lousberg . The efforts were closely related to the beautification of the city ("embellissements") ordered by Napoleon in 1804, which included the "repair and beautification of the baths" as well as the creation of "walks" on the filled trenches of the outer city fortifications. The idea of planting the Lousberg is said to have originated in 1806 and was promoted by the General Secretary of the Prefecture of the Roer Department , Johann Wilhelm Körfgen (1769–1829). The idea of a park on the Lousberg was combined with the idea of building a social building called “Belevedere” on the south-eastern slope of the mountain. To this end, various citizens, chaired by Körfgens, joined a specially formed joint-stock company, the aim of which was to stimulate tourism. While the public purse had to provide the land for the project and put the plantings into operation, it was the responsibility of the private stock corporation to raise the construction costs for the community building. The prefect of the Roer-Département Alexandre de Lameth commissioned the first plantings on the Lousberg in 1807. The plans for the park, which were based on the principles of the English landscape garden , were provided by the Düsseldorf court gardener Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe on behalf of Lameth , who had also been commissioned by him to submit plans for the redesign of the outer city moats. A "Committee for Embellissements" founded in 1807 oversaw the entire project. The Lousberg, which had previously been more or less bare and used as a sheep pasture, was transformed into a forest park with extensive trees by 1818. The society house was built between 1807 and 1810. Already in 1818 its dilapidation was complained. In 1827/28, under the direction of Adam Franz Friedrich Leydel, renovation and expansion were carried out. On August 29, 1836, the society house burned out completely after a ball. In 1838 it was restored in the classical style according to plans by Leydel, and later renovated and expanded according to plans by Friedrich Joseph Ark . Under the name Belvedere , it functioned both as a restaurant and a casino. Along with other staffages, including the Tranchot Obelisk, a monopteros on the site of today's rotating tower and a small Chinese pagoda , it was a popular destination for walkers. The circular route, starting at the place of today's bronze statues through the recently restored beech avenue on the north slope, offered the spa guests and citizens various views of the city and the surrounding area until all directions of view came together at the obelisk. The route itself was also laid out dramatically by Weyhe, alternating between flat stages and inclines of various lengths.

His country estate Müsch , which was located on the northern flank of the Lousberg in the Soers , was transformed into a ferme ornée between 1803 and 1814 by General Secretary Johann Wilhelm Körfgen - in accordance with Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe's Lousberg plans . Weyhe's son Joseph Clemens Weyhe developed the 11 hectare park area of the estate into today's Müschpark in 1866 .

At the end of the 19th century, the plans of the Aachen gardening director Heinrich Grube (1840–1907) added the Lousberg park areas in an easterly direction around the areas of the Salvatorberg , so that a network of green spaces with the city fortifications (northern Parts of the avenue ring) and with the today's Stadtgarten Aachen , designed by Peter Joseph Lenné in 1852 .

In 1906 the city of Aachen rebuilt the Kerstenschen Pavilion , a baroque building built by Aachen architect Johann Josef Couven , on the Lousberg. The pavilion, which is around 100 years older than Lousberg Park, was previously located in the city of Aachen at Annuntiatenbach 22–28 and was part of the city palace of the wealthy dye works owner Nicolaus Mantels. To save the building from demolition, the city bought it and had it rebuilt on Lousberg. The pavilion has been looked after by the Lousberg Society since 2005 and is used for exhibitions and lectures.

The open-air theater on Lousberg, which was built like a Greek theater on the hillside facing the city, failed not least because of the Aachen weather.

During the Second World War , the Belvedere Society House and other structures in the park were destroyed. The remains of the pillars of the Belvedere can still be seen today and are colloquially known as the “Aachen Acropolis”.

The Belvedere water tower was built in 1956 to maintain the water supply in the western residential areas . This became superfluous in the 1980s because of the more powerful pumps, which is why the operation as a water tower was completely discontinued in 1988. After major renovations, it is mainly used as an office building. The rotating café on the top floor of the building is only open on Sundays.

Today the Lousberg is largely forested and serves as a local recreation area. The extensive park of the former St. Raphael Monastery to the north of Lousberg was integrated into Lousbergpark in 2009. In addition, the Lousberglauf and the open air literature festival "Leselust am Lousberg" take place once a year in summer on the Lousberg.

The Lousberg legend

The following legend exists about the origin of the Lousberg:

The Aacheners had tricked the devil into building the Aachen Cathedral . When they ran out of money for the cathedral, they made a pact with the devil. In exchange for a considerable amount of gold, they promised him the soul of the first living being to enter the cathedral. Instead of a human soul hoped for by the devil, the Aacheners hunted a wolf into the cathedral that they had caught in the Ardennes . When the devil discovered the fraud, he slammed the heavy bronze door of the cathedral so hard that his thumb got stuck in the door and was torn off. The thumb is still stuck in one of the two “wolf heads” on the cathedral door (in fact, they are lion heads) - and those who manage to pull out their thumbs receive a golden dress from the cathedral chapter.

The antique animal sculpture set up in the vestibule of Aachen Cathedral, which probably represents a she- bear , is often interpreted in Aachen as an image of the wolf, whose soul had fallen victim to the devil.

The devil was looking for revenge and wanted to bury the cathedral forever. To do this, he collected tons of sand on the North Sea coast, which he filled into huge sacks and carried towards Aachen. When he had to breathe with his load because the day was very hot, an elderly, poorly dressed woman came towards him. The devil asked her how far he still had to drag. But the woman was “lous”, which means “smart” in the Aachen dialect. She had recognized who was sitting in front of her by his horse's foot and tail. So she said that she came from the Aachen market, which was terribly far away. As she did so, she pointed to a rock-hard piece of bread that she was carrying in a basket and to her worn shoes. She would have bought both new on the market. The devil was so annoyed at the prospect of having to drag his load that far that he left it where it was. In another variation, the farmer's wife holds a cross towards the devil as he stares at her shoes, whereupon the devil drops the sandbag in pain. The mountain was created through the cunning of the market woman and got its name from the term "lous".

Today a bronze group of statues on the Lousberg, depicting the devil and market woman, commemorates the legend and was created in 1985 by the Aachen artist Christa Löneke-Kemmerling, wife of the Aachen sculptor Hubert Löneke . In the original version of the devil figure, she still had both thumbs, which of course is not compatible with the background story of the construction of the Aachen Cathedral. This “malpractice” was probably remedied by Aachen citizens in a nocturnal action and the artist later blinded the corresponding spot; the original of the bronze thumb has not appeared again to this day.

In addition, the Aachen proverb has survived: “De Oecher send der Düvel ze lous” (Aacheners are too clever for the devil).

literature

- Daniel Schyle: The Lousberg in Aachen. A Neolithic flint mine with ax blade production (= Rhenish excavations . 66). von Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4326-8 .

- Thomas Terhart: The Lousberg Park in Aachen (= Rheinische Kunststätten . 338). Neusser Druckerei und Verlag, Neuss 1988, ISBN 3-88094-611-6 .

- Jürgen Weiner: The Lousberg - flint mining in the Neolithic. A guide to the prehistoric section of the Frankenberg Castle Aachen City History Museum. Museums of the City of Aachen, Aachen 1984.

- Jürgen Weiner: The Lousberg in Aachen. A flint mine from the Neolithic Age . In: Hansgerd Hellenkemper , Heinz Günter Horn , Harald Koschik (Ed.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe (= writings on the preservation of monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia. 1). von Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 139-142.

- Jürgen Weiner: The Lousberg in Aachen. Flint mining 5500 years ago (= Rheinische Kunststätten. 436). Rhenish Association for Monument Preservation, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-88094-842-9 .

Web links

- Entry for Waldpark Lousberg in the European garden network EGHN in the database " KuLaDig " of the Rhineland Regional Association

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Dorothée Hugot: History of the Lousberg. Lousberg Gesellschaft, accessed January 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Christian Quix : Historical-topographical description of the city of Aachen and its surroundings. DuMont-Schauberg, Cologne et al. 1829, p. 125 .

- ^ Roland Walter: Aachen and the northern area. Mechernicher Voreifel, Aachen-South Limburg hill country and western Lower Rhine Bay (= Geological Guide Collection . Volume 101 ). Gebr. Borntraeger, Berlin et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-443-15087-7 .

- ↑ Thomas Terhart, Raimund Mohr: The Lousberg. Its history, its transformation into a forest park according to the plan of Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe and its importance for Aachen today. Student thesis at the Chair of Building History at RWTH Aachen University, Aachen 1987.