European yew

| European yew | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Leaves and aril of the European yew tree ( Taxus baccata ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Taxus baccata | ||||||||||||

| L. |

The European yew ( Taxus baccata ), also known as the common yew or just yew , formerly known as Bogenbaum, Eue, Eve, Ibe, If, Ifen, is the only European species in the yew ( Taxus ) genus . It is the oldest (tertiary relic ) and shade- friendly tree species in Europe. She can reach a very old age. Except for the seed coat, which is vividly colored red by carotenoids when ripe , the arillus , which surrounds the seed like a cup, and the yew pollen , all parts of the plant of the European yew are highly poisonous. The European yew is one of the protected plant species in all European countries. In Germany it is on the red list of endangered species (hazard class 3: endangered) and was tree of the year in 1994 and poisonous plant of the year 2011. In Austria it was tree of the year in 2013.

The decline of the yew tree is often associated with the expansion of the beech ( Fagus ) around 2000 years ago. However, the strong expansion of the beech cannot be solely responsible for the disappearance of the yew, as the yew is often found in beech forests, where it grows in the shelter of the beech. The beech may have contributed to the disappearance of the yew tree, but its endangerment is due to centuries of overuse by humans.

The wood of the yew has always been valued by humans because of its extraordinary hardness and toughness. Accordingly, its use goes back a long way. The oldest evidence of the use of yew as a tool forms the spearhead of Clacton-on-Sea from the Holstein interglacial about 300,000 years ago. The lance from Lehringen comes from the Eem warm period about 130,000 years ago . The famous " Ötzi ", the glacier mummy, which was found in the Ötztal Alps in 1991, lived 5200 years ago and carried a bow stick about 1.80 meters long made of yew wood. The handle of his copper ax was also made of yew wood.

While the use of yew trees in forestry is no longer of economic importance, the pruning-compatible yew trees have been used frequently in garden design since the Renaissance . They were and are mainly planted as evergreen, cut hedges.

description

Appearance

The evergreen European yew is a very variable species in its shape, which grows as a tree or shrub depending on the site conditions . In extreme locations such as high mountains or on rock faces, it even grows as a creeping shrub.

The appearance of the yew tree changes with age. Young yew trees usually have slender trunks with regular branches. The crown of young trees is broadly conical and develops into a round, egg-shaped or spherical shape with increasing age of the tree. Freestanding yew trees are often branched to the ground. Older specimens are also often multi-peaked and multi-stemmed.

The thin gray to reddish brown scale bark of the yew trunks is characteristic and striking . Initially, the trunks of young yew trees have a reddish-brown, smooth bark, which later turns into a gray-brown bark that peels off in scales. In Central Europe only very few trees reach heights of growth over 15 meters. In the north of Turkey , however, there are monumental yew trees that reach heights of 20 meters, and in the mixed forests of the Caucasus there are isolated yew trees that are up to 32 meters high.

Young yews usually have a trunk with a clear main axis, while sexually mature yews are often multi-stemmed. When young, the yew grows extremely slowly. In unfavorable conditions, it remains at a height of 10 to 50 centimeters and forms a small crown. If the conditions are favorable, it will take at least 10–20 years for it to grow out of the roe deer's ears. After that it grows up to 20 centimeters annually in good conditions.

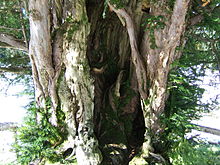

The height of the yew tree grows from an age of approx. 90 years. On the other hand, the growth in thickness and crown never stop. Trunk diameters of over one meter are possible. Due to its high vegetative reproductive capacity , root saplings , shoot stems and the rooting of branches that touch the ground are characteristic of the European yew. The intergrowth of individual trunks can result in complex trunks up to 1 meter thick .

From an age of around 250 years, yew trees often develop core rot inside the trunk, which over the course of centuries can lead to an almost complete hollowing out of the tree. The core rot makes it almost impossible to determine the exact age of old yew trees, as there are no annual rings inside the trunk from which the age of a tree could be read. Age is therefore mostly estimated.

It is characteristic of the age phase of European yew trees that, despite the hollowed trunk, the tree initially has a fully developed crown until the hollowed-out trunk can no longer bear the weight of the crown and parts of the tree break away. There then remain circular or semicircular stem fragments which, under favorable circumstances, can be supplemented by new shoots from the tree stump or the root system.

Old yew trees have two strategies at their disposal by which they can replace a trunk that is rotting away from the inside: In the hollow interior of the trunk, they occasionally develop inner roots that can develop into a new trunk. Alternatively, stem-borne shoots can grow up vertically on the outside of the primary stem, so that very old yew trees occasionally only consist of such a wreath of strongly thickened and fused shoots.

The needles

The soft and flexible yew needles have a linear shape that is sometimes slightly curved into a sickle shape. They are in a spiral shape on the main shoots, while they are arranged in two lines on the side branches. Yew needles are between 1.5 and 3.5 centimeters long and between 2 and 2.5 millimeters wide and can reach an age of three to eight years before the tree sheds them.

Yew needles are also known as dorsiventral , which means that they have a clearly distinguishable top and bottom. They are glossy dark green on top and have a raised median nerve that ends at the tip. On the other hand, they are colored light or olive green on the underside. While yew needles have no cleft opening on the top, there are two indistinct, pale green ostomy bands on the bottom .

Yew needles have several striking characteristics. They do not have a subcutaneous tissue ( hypodermis ) mechanically reinforced by sclerenchyma and there are no resin canals .

The root system

European yew trees have a very extensive, deep and dense root system. The development of this root system has priority over the growth in thickness and height as the tree grows. European yews are able to penetrate even heavily compacted soils.

The root system, which is strongly developed in comparison with other tree species, also enables the tree to have a high regenerative capacity, where even after a complete loss of the trunk, saplings can still grow. With its diverse and flexible root system, the yew tree is insensitive to fluctuating moisture, temporary moisture and a lack of air in the soil. This shows their high individual adaptability to different locations and living conditions.

In rocky regions, the European yew tree is able to penetrate water-bearing depressions and crevices with its roots, while it clings to bare rocks.

The yew tree has a fungal root of the VA mycorrhiza type , so yew trees are one of the few forest trees whose roots do not enter into a symbiosis with fruiting mycorrhizal fungi.

Cones, seeds and propagation

Under optimal site conditions, yew trees bear female cones for the first time when they have reached an age of 15 to 30 years. Sexual maturity can be significantly delayed under less favorable site conditions. Yew trees standing in dense stands of trees that do not receive sufficient light sometimes only reach sexual maturity at the age of 70 to 120 years. The cones are set up in late summer. The flowering time is in late winter or early spring of next year, usually between February and March, in colder regions between April and May.

The European yew is usually dioecious ( dioecious ): male and female cones are on different trees. Exceptional cases are monoecious ( monoecious ) specimens with cones of both sexes on a tree. Usually only a single branch has flowers of the opposite sex.

The numerous male cones are on 1 to 2 mm long, axillary shoots. They have a spherical shape with a diameter of about 4 mm and contain 6 to 14 shield-shaped stamens , each carrying 6 to 8 yellowish pollen sacs. When the pollen sacs open due to heat, the pollen grains are carried away by slight wind movements. Although the pollen grains of the European yew tree have no air sacs, because of their low weight their sinking speed of 1.6 cm per second is so low that they can be carried very far away by air movements. The early flowering time, which falls in a period in which deciduous trees usually do not yet have leaves, ensures that this pollen flight can take place largely unhindered, even if the respective yew is covered by deciduous trees.

The female cones are only 1 to 1.5 mm in size, each stand as short shoots in the leaf axils of younger branches and are inconspicuous due to their greenish color. They consist of overlapping scales, only the topmost of which is fertile and has only one ovule. At the time of flowering, a droplet of pollination forms at the tip of the wrapper. This picks up the pollen grains as it approaches and, when it has evaporated, brings the pollen grains to the nucellus so that the cones are pollinated. At the base of the ovule, an annular bead in fertilized flowers to a fleshy, slimy seed coat, which is Arillus , grows. This surrounds the seed like a cup, its color changes from green to a striking red with increasing ripeness. Due to the aril, the yew seed is often incorrectly referred to as a fruit or even a berry. This is not botanically correct, as there is no ovary in the nude-seeded plants that would be necessary for fruit development. The red seed coat is edible and non-toxic, only the seeds are toxic. The flower buds are formed in the second half of summer.

The bluish-brown and egg-shaped seed is 6 to 7 mm long and 3 to 5 mm wide. The weight of the semen is between 43 and 77 mg. The formation of the seed coat has European yew trees in common with the other species from the yew family . The seeds ripen from August to October and only germinate in the second spring. The seeds are dispersed by birds , which are attracted by the sweet aril. The aril is digested and the seed passes through the digestive tract undamaged. In this way, birds ensure that the yew seeds spread.

For generative propagation by sowing, the seeds are collected as soon as the aril turns red and the seeds turn brown. The seed coat is removed with a jet of water and the seeds are then stored until the next autumn. The germination success is greater than 50% if the seeds are stratified before sowing, i.e. are subjected to a heat and cold treatment lasting several months, which mimics the change of the seasons.

The chromosome number of the species is 2n = 24.

Systematics

The Taxaceae (yew-like) are assigned to the gymnosperms (naked samers) and within these to the conifers (conifers). Interesting is the lack of cones typical for this group of yew trees; the fleshy aril (erroneously colloquial “berry”) arises from the stem of the ovule. The yew family includes a total of five genera ( Amentotaxus , Austrotaxus , Pseudotaxus , Torreya , Taxus ), all of which form seeds with an aril. The genus Taxus is considered to be a taxonomically difficult group, the different species mostly have adjacent but not overlapping areas (parapatric distribution), but are morphologically difficult to tell apart. This is especially true for the occurrences in the Himalayas and China. Different taxonomists have already distinguished between 2 and 24 species. More recent studies, it was clear that the occurrence of specified by previous botanists Taxus baccata do not belong to this type in the Western Himalayas, but form a separate species, Taxus contorta ( syn. Taxus fuana Nan Li RRMill) is this, according to molecular data ( Comparison of homologous DNA sequences) the sister species of Taxus baccata . According to the genetic data, the European yew, despite its large distribution area, is a monophyletic unit and the only species native to Europe.

distribution

The occurrence of Taxus baccata L. is not limited to Europe, its distribution area extends from the Azores , the Atlas Mountains in Northwest Africa through Europe , Asia Minor to the Caucasus and Northern Iran . In the north, the limit of distribution runs from the British Isles via Norway to Sweden and Finland . The eastern distribution ranges from Latvia , along the Russian-Polish border, to the eastern Carpathians and ends in northern Turkey. In the south, the distribution limit runs south of Spain , over parts of Morocco and Algeria , to southern Turkey and from there to the interior of northern Iran.

In Europe, the distribution area is not contiguous, but rather divides into several sub-areas and is severely torn. Often the yew only occurs in small stands or as a single tree. The cause of this disjunction (disruption) is most likely the anthropogenic overexploitation of the yew stands in earlier times.

Natural yew trees exist mainly in northern Portugal , Spain, Brittany and Normandy in northern France, on the British Isles , southern Scandinavia , the Baltic States , the Carpathians, on the northern Balkan peninsula , in northern and central Italy , Corsica and Sardinia . On the other hand, it is absent in Denmark , northern Belgium and Holland as well as along the lower and middle Elbe and Saale . It is also absent in the interior of Poland , while it occurs in the coastal region of the Baltic Sea.

The distribution area of the European yew tree is largely determined by its low frost hardiness. Its northern limit runs at 62 degrees 30 minutes N in Norway and 61 degrees N in Sweden, roughly on the January isotherm of −5 degrees Celsius. It thrives above all where the climate is characterized by mild winters, cool summers, lots of rain and high humidity. In the Bavarian Alps it occurs up to an altitude of 1350 m , in Valais up to an altitude of 1600 m .

( See also: Treatise on the occurrence of yew trees in Thuringia)

Hazard and protection

The Yew is in the red list of the IUCN 'not at risk' (least concern) listed with a "rising" trend (Increasing).

In Germany , the yew tree is listed on the Red List as "endangered" (level 3), with age group management with clear-cutting operations and game browsing being given as the main reasons for risk. Since the Federal Species Protection Ordinance came into force (January 1, 1987), wild populations of the yew tree have been under special protection . On behalf of the Federal Agency for Agriculture and Food (BLE), the occurrence of the European yew tree in German forests was recorded as part of the project recording and documentation of genetic resources of rare tree species in Germany from 2010 to 2012 . A total of 342 yew occurrences with a total of 60,045 trees were recorded. The federal states with the most yew trees were Thuringia with 33,200 yew trees and Bavaria with 14,700 yew trees. The main areas of distribution are in the Central German Triassic mountain and hill country, in the Swabian Alb, in the Franconian Alb and in the Upper Palatinate Jura as well as in the Swabian-Bavarian young moraine.

In Switzerland , the European yew tree is classified as “not endangered” in the red list of the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) . But it is regionally (cantonal) protected.

Location requirements

The yew tree is vague, i.e. H. it thrives in damp, damp and very dry, as well as in acidic and basic locations. The ecogram of the yew tree shows the very large physiological amplitude of this tree species, which in dry areas even goes beyond wooded areas and can withstand changing conditions. The yew tree is often found on fresh, humus or sandy loam, but it also thrives in damp and even sandy locations. As with all other tree species, however, the growth of the yew is favored on well-rooted and nutrient-rich soils. It occurs equally on calcareous sites, silicate rock soils and organic substrates. The European yew tree prefers fresh, nutrient-rich, often alkaline soils in oceanic, humid climates. Their optimum precipitation is over 1000 mm / year. However, it is also able to meet its water requirements from wet or boggy special locations in areas with generally less precipitation. It can even be found in floodplains, which indicates a tolerance to a lack of oxygen in the soil.

The European yew is the most shade-friendly tree species in Europe. At a temperature of 20 degrees it can still survive with an illuminance of 300 lux . Young yews are obligatory shade plants, which means that they only thrive in the shade, especially in a shady shelter under other trees. Mature yews, on the other hand, can withstand full sun. While European yew trees do not thrive in forests with a completely closed, evergreen canopy, as is typical for a pure spruce stand, five percent of the amount of light in the field is enough for them to successfully form flowers and seeds. They thrive best in sparse mixed forests, especially in mixed forests of oak , beech , fir and hardwood, but only when the wild population is so low that young regrowing plants are not immediately bitten. In the Carpathian Mountains , for example, they represent 12.4 percent of the logs, 13.5 percent of the base area and 4 percent of the wood supply. The European yew is one of the so-called climax forest tree species, which means that it can successfully naturally rejuvenate in a plant community that has developed at the end of a succession . Pure yew stands, on the other hand, are rare. They usually arise because the old age that yews can reach allows them to outlast the other tree species in whose shade they previously grew.

European yew trees can now only be found in inaccessible ravine forests and on steep slopes due to earlier overexploitation, targeted extermination and game browsing. They were often fought as " unwood " and horse and chicken poison. Further reasons for the rarity of the yew are the conversion of forestry from plenter-like interventions to abrupt economy, which disadvantages the slow-growing yew, which is sensitive to sudden release. A high game population also prevents natural population regeneration because of browsing . Your last retreats are often shady and steep mountain slopes, also avoided by game, but which have to be water-rich.

Survival strategies

Regenerative ability

The regenerative capacity of the yew is strongest compared to all other native conifers. The high regenerative capacity of the yew is shown on the one hand in the fact that it is the only conifer species capable of knocking out of the stock . On the other hand, thanks to its very good wound healing (wound overburden), it also manages to withstand major damage. The yew tree is able to react to mechanical damage as well as frost or sunburn damage through the formation of reiterations until old age. These repeat shoots are used to renew the crown and give trees the opportunity to replace aging branches. Another survival strategy is vegetative reproduction. This asexual reproduction is based on mitotic cell division . The daughter generation therefore does not differ in its genetic material from the mother generation; she is a clone. The high vegetative reproductive capacity is demonstrated by the following abilities: The formation of knot kernels can absorb additional nutrients and complete rejuvenation of an individual yew tree. If trees have fallen, vertical branches immediately sprout. Branches that come into contact with the ground begin to knock out roots.

Drought resistance

Although the needles of the yew tree have neither sclerchymatic reinforcements nor protective wax droplets in the stomata, they are considered to be extremely drought-resistant. The yew can withstand a similarly high relative water loss as the common pine ( Pinus sylvestris ). Both have similarly high absolute water reserves (based on the same weight) as herbaceous, sap-rich plants, although their water capacity (water content at saturation) is comparatively low. As a result, the yew tree in relation to its dry weight is able to withstand much higher water losses, even up to 45% of its weight. Another ability that protects the yew from drying out is the quick closing of the stomata . Comparative studies of fir and yew needles show that the yew reacts to a water saturation deficit with a stomatal closure four times faster than the fir ( Abies ).

Frost hardiness

The yew's winter survival strategy is based on two components. On the one hand, the perspiration is reduced to a fifth to a twentieth compared to summer. The colder the ambient temperature, the higher the restriction. On the other hand, the yew increases the cell sap concentration. This leads to a lowering of the freezing point. Together with the freezing point, the temperature minimum for net assimilation also decreases from approx. −3 ° C to approx. −8 ° C. As long as the yew tree has enough time to prepare for exposure to the cold in order to increase its cell sap concentration accordingly, freezing damage only occurs at very low temperatures of below −20 ° C. Much more frequent damage is caused by frost drought, which can be traced back to the relatively poor perspiration protection of the yew needles. This drying-out damage mostly only occurs in exposed, free-standing trees. The yew tree is also insensitive to late frosts. It achieves this by the fact that the cell sap concentration that has increased over the winter is only slowly broken down. As a result, this winter hardening persists long into the growing season. The normal values of the previous year will not be reached again until June.

Shadow tolerance

The yew is considered to be an extremely shade-tolerant tree. It is able to survive in the secondary stock even if it is completely shielded. Compared to the classic shade tree species such as fir and beech, it tolerates significantly more shade. As with the occurrence of a water deficit, the stomata close quickly even when darkened. They only open after the light compensation point has been exceeded . However, the yew can achieve positive net assimilation even with low light intensity. The light compensation point, i.e. the point at which positive net assimilation is just possible, is around 300 lux for the yew at a temperature of 20 ° C. In comparison, other shade-bearing tree species such as the beech reach 300-500 lux and the fir ( Abies ) to 300–600 lux. A typical light tree species like the white pine ( Pinus sylvestris ), on the other hand, requires values of 1000 to 5000 lux to exceed the light compensation point.

Toxicity

Wood, bark, needles and seeds contain toxic compounds that are collectively referred to as taxanes or taxane derivatives ( diterpenes ). In detail, taxin A, B, C as well as baccatins and taxols can be detected. The content of toxic compounds is different in the different parts of the tree and fluctuates depending on the season and the individual tree. The seed coat of the tree, however, is not poisonous and tastes sweet. The taxol content of the wood is very low, however, at 0.0006%.

The toxic compounds are quickly absorbed in the digestive tract in humans and other mammals. Symptoms of poisoning can occur in humans as early as 30 minutes after ingestion. The toxic compounds have a damaging effect on the digestive organs , the nervous system and the liver as well as the heart muscles . There is no antidote. The symptoms of poisoning include an acceleration of the pulse, dilation of the pupils , vomiting , dizziness and poor circulation , and unconsciousness. Even an intake of 50 to 100 grams of yew needles can be fatal for humans. In shredded or chopped up form, the needles are five times stronger. Death occurs from respiratory paralysis and heart failure. People who survive such poisoning usually suffer permanent liver damage.

Horses , donkeys , cattle as well as sheep and goats react to different degrees of sensitivity to the toxic compounds contained in yew trees. Horses are considered to be particularly at risk - consuming 100 to 200 grams of yew needles is said to lead to death. In cattle, symptoms of poisoning occur at around 500 grams. Grazing animals are particularly at risk if they suddenly ingest large quantities. On the other hand, cattle, sheep and goats seem to develop a tolerance to the toxins of the European yew tree if they are used to regularly eating smaller amounts of them. In a scientifically documented case, goats damaged relatively thick yew trees ( BHD > 30 cm) by peeling the (also poisonous) bark in such a way that they died over time. The goats themselves showed no signs of intoxication. The death of many grazing animals by eating yew has been empirically confirmed; therefore, apparently deviating individual findings must be handled extremely carefully. The poisoning occurs in the small ruminants especially in autumn and winter when there is a lack of feed on the pasture. In rabbits , less than 2 grams of needles are said to be fatal. There is no effective therapy for yew poisoning. Roe deer and red deer are insensitive to the poisons of the yew trees and are therefore responsible for damage caused by game browsing .

The yew as a medicinal plant

In folk medicine, the fresh twig tips were used as a remedy for worm infestation , as a heart remedy, to promote menstruation , and as an abortion agent. Because of their toxicity, these uses are considered too risky by modern medicine.

Active ingredients are diterpene alkaloids from the taxane -type, Baccatin III (the mixture was referred to as "taxine"), cyanogenic glycosides , such Taxiphyllin , biflavonoids such as sciadopitysin and ginkgetin .

In homeopathy , Taxus baccata ( HAB ) is used against digestive weakness and skin pustules.

In the 1990s, the European yew succeeded in producing the cell division-inhibiting substance paclitaxel , which could previously only be isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew, Taxus brevifolia , partly synthetically from the taxane compounds of the needles, especially baccatin III . Another substance was added later, docetaxel . These substances are approved for chemotherapy of metastatic breast and ovarian cancer as well as certain bronchial carcinomas .

Yew community

Accompanying tree species and herb layer

Typical accompanying tree species of the European yew are in Central Europe stalk and sessile oak , hornbeam , ash , elm , linden , white fir and sycamore . It finds its optimum in deciduous forests with deep, fresh, nutrient-rich soils, for example in forests of fir-beech and pedunculate oak with a lot of precipitation. In the dry climate of the Mediterranean countries, it grows in the company of Mediterranean oak species such as the holm oak or the plane trees .

In open cultivated land, European yew trees often grow between thorny hedge bushes such as sloe or dog rose , which protect the young plants from being bitten by wild animals and grazing animals.

If the herbaceous layer in mixed yew forests consists of ferns and mosses, and often consists of ringelkraut , wild strawberries , gundermann , ivy , blackberries and violets , in yew-beech forests you will find single-flowered pearl grass , woodruff or lime blue grass . Where the Yew is particularly associated with oak trees, often found in the herb layer primrose and bellflower .

Birds

In the case of bird species that use the European yew as a food crop, a distinction is made between seed-spreaders, which are only interested in the sweet aril and excrete the seeds again, and seed-eaters. Among the seed dispersers are particularly Star , song thrush , blackbird and Mistle Thrush and juniper , red and Ring Ouzel . Mistle thrushes show a territorial behavior and defend "their" yew tree against other birds from late summer, so that yew trees occupied by mistletoe thrushes still have red seed cups until January and February. This behavior also applies to song thrushes. However, these show less willingness to defend themselves than mistletoe. Arillen are also from Sperling , Redstart and the blackcap and acorn and nutcrackers , Waxwing and pheasant consumed. All of these bird species are significantly involved in the spread of the European yew tree and ensure that yew shoots grow far away from established yew stands and in inaccessible places such as steep rocky slopes.

The seed-eaters include the greenfinch and, to a lesser extent, bullfinches , great tit , grosbeak , nuthatch , green woodpecker , great spotted woodpecker and occasionally the marsh tit . Nuthatches rub the seed coat on tree bark before, like woodpeckers, they wedge the seed in cracks in order to hammer it open. The greenfinch, on the other hand, loosens the aril with its beak, removes the glycoside-containing seed coat and then eats the inside of the seed.

Mammals

Dormice such as hives and tree dormice climb yew trees to get to the red arils. As a rule, however, mammals will eat the seed cups that have fallen to the ground. Small rodents such as bank vole , wood vole and yellow-necked mouse are among the species that enjoy it, among other things. Their presence attracts predatory mammals such as red fox and weasel and polecat . Red foxes like badgers , brown bears and wild boars like to eat the arilles and this has already been described for pine marten .

Rabbits and hares bite young yew seedlings and thus hinder the growth of young trees in height and width. However, much greater grazing pressure comes from red deer , which is insensitive to the toxic compounds contained in the yew tree. In particular, a high population of deer prevents the natural rejuvenation of the yew population : young saplings tear them up with their roots while grazing. The branches of yew trees are eaten up to a height of about 1.4 meters. Even goats and sheep grazing on yew trees. The gray squirrel, which was introduced to Europe from North America, has also proven to be a noteworthy yew pest . It peels off the bark of older yew trees too, so that the trees are at risk from wound infections.

Invertebrates

In comparison to other European tree species, only relatively few invertebrates are found on European yew trees. One of the most important of these is the yew gall mosquito ( Taxomyia taxi ), whose larvae nest in the buds of the shoot tips and which sometimes lead to an overproduction of yew needles, so that a bile reminiscent of artichokes is formed. Two parasitic wasps, namely Mesopolobus diffinis and Torymus nigritarsus , in turn lay their eggs in the galls or in the fully developed larvae and pupae of the yew gall mosquito. The caterpillars Ditula angustiorana ( winder ) and blastobasis vittata ( Blastobasidae ) eat, among other yew foliage. In the sapwood of the yew trees, the larvae of the house goat ( Hylotrupes bajulus ) and the pied rodent beetle ( Xestobium rufovillosum ) can be found. The the weevils scoring furrowed weevil ( Otiorhynchus sulcatus ) damages year yew shoots and roots of young seedlings and their tops shoots. The yellowish to brown colored yew bowl louse ( Eulecanium cornicrudum ), which sucks on young shoots, can also be found.

The wood of the yew

Properties and current use

The European yew is a heartwood tree . Heartwood describes the dark, inner zone in the trunk cross-section that is physiologically no longer active and which is clearly different from the outer, light sapwood. The narrow sapwood is yellowish-white and about ten to twenty annual rings thick. The heartwood is reddish brown in color. The wood, which is fine-ringed because of the slow growth, is very durable, dense, hard and elastic. The durability of the heartwood results from the storage of tannins, which impregnate the wood. Despite its durability, yew wood is vulnerable to the common rodent beetle . One cubic meter of yew wood weighs between 640 and 800 kilograms. In comparison, one cubic meter of wood from the sequoia tree 420, the pine 510 and the beech and oak weighs 720 kilograms each. Yew wood dries very well, shrinks only moderately and is easy to work with. However, the European yew tree no longer has any major forestry significance. The wood, which is seldom available in the timber trade, is used for veneering , wood carving and art turnery as well as for the construction of musical instruments .

Use in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages

In the history of mankind, yew wood has had a much greater importance than is attributed to wood today. The hard and elastic wood is particularly suitable for the construction of bows and spears: The oldest known wooden artefacts after the Schöningen spears are two spears , each made of yew wood. The older spear was found near Clacton-on-Sea , Essex and is dated to be 150,000 years old. The second find comes from Lehringen in Lower Saxony , where a 2.38 m long yew wood lance was found in the chest of a forest elephant skeleton preserved in a marl pit , which is attributed to the Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals and is estimated to be 90,000 years old. Eight yew arches, which were found in various excavation sites in northern Germany, are between 8000 and 5000 years old. A yew arch, which is also very well preserved and 183 centimeters long, was found in 1991 on the Ötztal glacier mummy . This bow is also 5000 years old.

Neolithic finds show the use of yew wood for the manufacture of everyday objects such as spoons, plates, bowls, needles and awls. Three Bronze Age ships found in the mouth of the River Humber in Yorkshire are made of oak planks bonded together with yew fiber. The remains of Bronze Age pile dwellings z. B. on Mondsee testify to this early appreciation of the yew wood, which is extremely moisture-resistant.

The longbow and its effect on the yew tree population

Initially built only from the heartwood of the yew tree, the different properties of sapwood and heartwood were used to make bows from around the 8th century. An English longbow is a type of bow with a stick from the late Middle Ages, which was mainly known for its massive use in late medieval battles. The rod made from one piece is about as long as the shooter, i.e. 180 centimeters, and consists of about 1/3 sapwood and 2/3 heartwood on the outside or inside.

The English archers were not serfs who were called up for military service, but highly trained soldiers who were contractually bound for a certain period of time and well paid. They could fight the enemy over a distance of over 400 meters. With them, English armies could defeat numerically superior forces.

An early deployment of numerous archers is documented for the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066, in which the Normans under William I defeated the English King Harald. Archers can be seen on both sides of the Bayeux tapestry . In the 13th century, the island's yew population declined sharply. The first indication of an import comes from a customs roll from Dordrecht , which is dated October 10, 1287. The arrival of six ships from Stralsund for Newcastle on January 8, 1295 is documented, which among other things had loaded 360 " Baculi ad arcus " or bow sticks . The Hundred Years War , from 1337, contributed decisively to the formation of national consciousness among the French and English; the population became more involved. So, Eduard III. 1339: "We hereby command that every man in good health in the city of London at leisure and on holidays use bows and arrows and learn and practice the art of shooting." (SCHEEDER 1994, p. 43) At the same time, games such as stone-throwing were played Throwing wood or iron, handball, soccer and cockfighting are prohibited under threat of prison. Every man between the ages of seven and sixty was required to have a bow and two arrows. Because of the shortage of wood and the strong demand, maximum prices had to be set so that everyone could afford a bow. "Since the defense of the empire was previously in the hands of the archers and there is now danger, We order that everyone must pay a fine of 2 shillings per bow to the king who sells one for more than three shillings and six pence" (SCHEEDER 1994, P. 7). In the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the Battle of Azincourt in 1415 near Arras , the English army inflicted heavy defeats on the French army through the use of trained archers with longbows.

Every merchant ship that wanted to trade in England from 1492 onwards had to carry a certain number of blanks from yew trees. This led to all European yew populations declining so much that they have not yet recovered properly. Between 1521 and 1567 alone, between 600,000 and a million two meter long and 6 cm wide yew sticks were exported from Austria and Bavaria for further processing into arches. In 1568, Duke Albrecht had to inform the imperial council in Nuremberg that Bavaria no longer had any yews that were ripening. In England, due to the shortage of yew wood, an order was issued that every bow maker had to make four per yew wood bow from the less suitable wood of sycamore maple, and young people under 17 years of age were prohibited from wielding a yew wood bow. Orders from this time suggest that England, after the central and southern European yew deposits were exhausted, obtained yew wood from the Carpathian Mountains and the northeastern Baltic States. In 1595 the English Queen Elizabeth I ordered the conversion of the English army from longbows to muskets. In his monograph on the yew, Fritz Hageneder takes the view that this change, which took place at a time when the longbow of the musket was still far superior in range, accuracy and shooting speed, was made solely because the raw material yew for the production of longbows was no longer available.

Other historical uses of yew wood

The use of yew trees wasn't just limited to making longbows. In addition to various utensils such as looms, boxes, buckets, combs and ax stiles , the moisture-resistant wood was used, among other things, for the so-called floor beams , which lay directly on the stone foundations of houses and were particularly easily exposed to moisture damage . The wood was also used for taps and water pipes. The elastic wood was used in the manufacture of whips until the 20th century. In contrast to longbow construction, yew wood was easier to replace in these uses.

Use as a poisonous, medicinal and food plant

The poisonous nature of the yew is already a topic of Greek mythology: Artemis , the goddess of the hunt, uses yew poison arrows to kill the daughters of Niobe , who had boasted of having a large number of children. The Celts Eibennadelabsud used to poison their arrowheads and Julius Caesar , in his Gallic Wars from a Eburons -Stammesfürsten who prefer using yew poison suicide committed, when the Romans to surrender. Paracelsus , Virgil and Pliny the Elder comment on the toxicity of the European yew tree . Dioscurides reported that Spanish yew trees were so toxic that they could be dangerous to those who just sat or slept in their shade.

Yew preparations played a role in medicine from the early Middle Ages. They were used to treat diseases such as epilepsy , diphtheria and rheumatism as well as rashes and scabies . Yew needle brew was also used as an abortion .

In addition to its use as a poisonous and medicinal plant, yew components were even used as food: the red and sweet seed coat, which is non-toxic, can be boiled down to make jam , provided the toxic seeds are removed. A small amount of yew leaves was traditionally added to the forage plants of the cattle in order to prevent diseases. In some regions, such as Albania, this is still practiced today.

Use as an ornamental plant

The yew tree is the only European softwood species that has a good deflection capacity. The pruning tolerance and the dense growth mean that yew trees were and are very popular as dense privacy hedges. Yew trees are also very suitable for geometric or figurative shapes . Starting with the Renaissance, the evergreen yew trees were therefore used in garden design. Cut hedges made from yew trees were particularly popular in baroque gardens . The gardens of Versailles are among the best-known baroque gardens in which yew hedges play a major role . The residential garden of Würzburg also has numerous yew sculptures. In England, walk-in labyrinths were made from yew hedges. The 114-meter-long and 52-meter-wide maze of Longleat House is bordered by more than 16,000 yew trees. With the turn to the English landscape garden , an increasing interest in unusual breeds began, which to this day has led to more than seventy different known cultivated forms of the European yew tree. These include:

- 'Adpressa': This shape, created in 1838, is often found in gardens. It grows as a (only female) bush with small, partly overhanging branches. The needles are elongated-elliptical and tapering to a point; they are only 1 cm long. There is also a yellow-colored form.

- 'Dovastoniana' (eagle wing disc): This form, first described in 1777, is about 5 to 8 m high and 6 m wide and grows with a single stem. The branches stand out horizontally; the tips and smaller side branches are overhanging. The needles are dark green.

- 'Fastigiata': Originally found in Ireland in the 1760s, this variety is widely used as a colonnade in parks, gardens and cemeteries. It grows very stiffly upright. The needles are very dark green and spiral around the branches. The summit usually grows with many shoots; this makes the crown wider at the top with age. On the British Isles , the columnar disk can reach a height of 15 m, in Germany it hardly reaches 5 m.

- 'Fastigiata Aurea': It grows in a similar way to the 'Fastigiata' variety, but has yellow needles differently from it.

- 'Fastigiata Aureomarginata': It becomes 5 m high and 2.5 m wide. The needles are golden yellow.

- 'Fastigiata Robusta': It grows similarly to the Sorrte 'Fastigiata', is up to 8 m high and 2 m wide. The needles are medium green.

- 'Fructo-luteo': Found in Ireland in 1817, this variety grows as a broad bush and has very dark green needles. The ripe seed coats are not red in color as in the species, but are colored yellow.

- 'Overeynderi': It grows as an egg-shaped shrub, is up to 5 m high and 3 m wide. The needles are dark green.

- 'Repandens' (pillow disc, table disc): It grows as a small shrub with flat spread, overlapping branches. After 10 to 15 years it becomes 0.5 to 0.6 m high, the final height is 0.8 to 1 m. The needles are glossy black-green on top and pale green on the underside.

Intersections

Taxus × media (cup grater) = Taxus baccata × Taxus cuspidata

Toponomics

The yew tree, also Ibenbaum (short Ibaum even Ybaum ) is eponymous for different geographic locations . Toponyms such as Eiben , Eibenberg , Ibenberg , Iberg , Yberg , Iberig and Ibach indicate historical yew stands .

Yew trees and yew trees worth seeing

Germany

In the vicinity of monasteries there is the greatest prospect of finding old yew trees.

- The largest German yew forest is the Paterzeller Eibenwald near the Wessobrunn monastery . In the 88 ha nature reserve in the Weilheim-Schongau district , over 1500 older yew trees grow in a species-rich mountain mixed forest .

- In Bovenden - Eddigehausen there is a large population of around 800 yew trees up to 200 years old.

- At Gößweinstein in Franconian Switzerland there is a beautiful population of around 4400 yew trees on the slope of the Wiesent valley. It has been designated as a natural forest reserve and is under nature protection .

- The yew tree on the Neuländer dyke is the oldest tree in Hamburg and a registered natural monument .

- The old yew tree from Balderschwang in the Oberallgäu district , which stands on an alpine meadow at an altitude of 1150 m above sea level, is estimated to be between 800 and 2000 years old. Their trunk consists of two separate parts with a circumference of two and 2.4 meters respectively.

- The Senckenberg yew in the Palmengarten, Frankfurt am Main is one of the oldest yew trees in Germany.

- The old yew tree on Haus Rath in Krefeld is 800 years old.

- The Ureibe near Steibis in the Oberallgäu district has a trunk circumference of 5 meters and is estimated to be 600 to 800 years old

- Near Fraudenhorst in the far north-east of Germany is probably the oldest group of yew trees, with an age between 500 and 800 years.

- In the so-called Ibengarten near Dermbach in the Thuringian Rhön there is an old yew tree population of around 600 trees.

- Harraser Leite nature reserve near Eisfeld with yew and beech forests.

- In the south of Thuringia near the municipality of Veilsdorf there is a 15 hectare deposit of yew trees on a northern slope.

- In Wörlitzer Park there is a yew grove with very beautiful old specimens, which were probably planted in the 2nd half of the 18th century.

- Kronberg Castle in Kronberg im Taunus has a yew grove and describes it as one of the last three yew groves in Germany.

- The 800 to 1000 year old Flintbeker yew at the Flintbeker Church in Flintbek / Schleswig-Holstein

- 1000 year old yew tree in Lebach near La Motte Castle (Saarland)

- the 1500-year-old yew tree on Gabler Strasse in Lückendorf

- A 1000-year-old yew tree stands in front of the police station in Xanten , Karthaus 14.

- The only larger yew occurrence in Baden-Württemberg , with almost 150 specimens, is in Höllental . It could have served as the namesake of the village Ibental and other places in the area.

Switzerland

- The oldest yew tree in Switzerland can be found in Heimiswil ( Emmental ). This tree, which is over 1000 years old, is located near the hamlet of Kaltacker and is also shown in the municipality's coat of arms.

One of the largest natural yew occurrences in Europe with around 80,000 yew trees can be found on the Albis mountain range, particularly in the Uetliberg area . The reason for this existence goes back to the liberalization of the hunting laws in Switzerland after the French Revolution. From 1798 to 1850, the livestock populations - in particular the ungulates - were hunted to the limit of extinction. Yew shoots are preferred by roe deer and have no chance of growing up with a larger roe deer population. The almost extinction of roe deer around 1860 made it possible for yew trees to grow, almost all of which are over 150 years old today. In 1997 the international yew conference took place in Zurich.

rest of Europe

- The " Fortingall Yew " is considered Europe's oldest tree; it is in the village of Fortingall in Perth and Kinross in Scotland ; their age is estimated to be 3,000 to 5,000 years.

- Two old yew trees frame the north portal of the Church of St. Edward in Stow-on-the-Wold in the Cotswolds in England .

- A number of very old yew trees can be found in the Norman departments of Orne , Calvados and Eure ( France ). There they decorate the churchyards of many villages. In La Haye-de-Routot , for example, there is a yew tree with a chapel closed by a door built into its hollow trunk. In the cemetery of Le Ménil-Ciboult ( Orne ) there is a yew tree with a trunk circumference of 12.5 meters.

- Harmanec , Slovakia

- Bakonywald , Hungary

- A yew forest on about 25 hectares, and thus one of the largest in the British Isles, exists on a carboniferous limestone plateau in south-western Ireland, in the Killarney National Park , the so-called 'Reenadinna Wood', with trees that are around 200 years old .

- The 18 hectare "Ziesbusch" (Slavic zis = yew) with 3500 trees in the Tucheler Heide , Poland

- Hennersdorf yew : the oldest tree in Poland, was considered the oldest tree in Germany until 1945

- Raciborski yew trees : 1000 year old group of yew trees in Poland

swell

- Christopher J. Earle: Taxus baccata. In: The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved December 15, 2010 .

literature

- Fred Hageneder: The yew tree in a new light. A monograph of the genus Taxus. Neue Erde, Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-89060-077-2 .

- Hassler-Schwarz Jürg: The yew tree (TAXUS BACCATA L.) A description with special consideration of the distribution and the cultural significance in the canton of Graubünden (Switzerland). 1999.

- Thomas Scheeder: The yew (Taxus baccata L.). Hope for an almost vanished forest people. IHW-Verlag, Eching 1994, ISBN 3-930167-06-9 .

- Christoph Leuthold: The ecological and plant-sociological position of the yew (Taxus baccata) in Switzerland . (= Publications by the Geobotanical Institute of the ETH, Rübel Foundation , Zurich. No. 67). Geobotanical Institute of the ETH, Rübel Foundation, Zurich 1980.

- Markus Kölbel, Olaf Schmidt (editor) and a .: Contributions to the yew tree . (= Reports from the Bavarian State Institute for Forests and Forestry, No. 10). Bavarian State Institute for Forests and Forestry, Freising 1996.

- Hugo Conwentz : The yew tree in West Prussia, a dying forest tree . Bertling, Danzig 1892.

- Angelika Haschler-Böckle: The magic of the yew forest . Neue Erde, Saarbrücken 2005, ISBN 3-89060-084-0 .

- Michael Schön: Forestry and Vascular Plants on the Red List. Species - locations - land use. 2nd Edition. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-89675-375-4 .

- The yew friend . Information leaflet for the members of the yew friends f. V. and others interested in the yew tree. Publisher: Cambiarare e. V. for the yew friends f. V., Sierke, Göttingen (published annually, since 1995).

- D. Featherstone: Bowmen of England. London 1967.

- H. Seehase, R. Krekeler: The feathered death. Hörnig 2001.

- U. Pietzarka: On the ecological strategy of the yew tree. Stuttgart 2005.

- Christina R. Wilson, John-Michael Sauer, Stephen B. Hooser: Taxines: a review of the mechanism and toxicity of yew (Taxus spp.) Alkaloids. In: Toxicon. Volume 39, Issues 2-3, 2001, pp. 175-185 (Describes toxicity to chickens).

- Ruprecht Düll , Herfried Kutzelnigg : Pocket dictionary of plants in Germany and neighboring countries. The most common Central European species in portrait. 7th, corrected and enlarged edition. Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim 2011, ISBN 978-3-494-01424-1 .

- Lutz Roth, Max Daunderer , Kurt Kormann: Poisonous plants plant poisons. 6th revised edition, 2012, Nikol-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-86820-009-6 .

- Ingrid and Peter Schönfelder : The New Handbook of Medicinal Plants, Botany Medicinal Drugs, Active Ingredients Applications. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-440-12932-6 .

Web links

- Taxus baccata in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: Conifer Specialist Group, 1998. Retrieved on December 31 of 2008.

- Distribution map for Germany. In: Floraweb .

- Thomas Meyer: Eibe data sheet with identification key and photos at Flora-de: Flora von Deutschland (old name of the website: Flowers in Swabia ) .

- Yew as a medicinal plant .

- The yew tree in Switzerland from ETH Zurich, Forest Management Group - Silviculture .

- Wolfgang Arenhövel: The yew tree ( Memento from March 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: Stiftung Wald in Not (Ed.): Rare Trees in Our Forests - Recognize, Preserve, Use , Pages 24–26 (PDF; 348 kB, via Wayback Machine).

- Info sheet Eibe, Botanical Garden, University of Vienna (PDF file; 53 kB).

- Pillar yew in Bamberg .

- On the cultural history of the yew tree from heimat-pfalz.de.

- Homepage of the yew friends .

- European yew. In: FloraWeb.de.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eibenforstamt Reinhausen ( Memento from July 2, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Lower Saxony Forestry Office Reinhausen, accessed on November 5, 2017

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 17 and p. 32.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Hecker: Trees and bushes. BLV Buchverlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8354-0021-5 , p. 166.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 16 and p. 17.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 17.

- ↑ Ulrich Hecker, Trees and Shrubs. P. 168.

- ↑ Toby Hindson: The growth rate of yew trees: An empirically generated growth rate. Alan Mitchell Lecture 2000, London 2000, Conservation Foundation.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 79.

- ↑ a b c d e Schütt, Weisgerber, Schuck, Lang, Stimm, Roloff (ed.): Lexicon of conifers. Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-933203-80-5 , p. 575.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 34.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 30.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Hecker, Trees and Shrubs. P. 169.

- ↑ a b Hageneder, p. 36.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 37.

- ↑ Schütt, Weisgerber, Schuck, Lang, Stimm, Roloff (ed.): Lexicon of conifers. Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-933203-80-5 , p. 577.

- ↑ Eibenbeeren on naturundfreiheit.de, accessed on November 19, 2016.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 43.

- ↑ Schütt, Weisgerber, Schuck, Lang, Stimm, Roloff (ed.): Lexicon of conifers. Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-933203-80-5 , p. 579 f.

- ^ Erich Oberdorfer : Plant-sociological excursion flora for Germany and neighboring areas . 8th edition, Stuttgart, Verlag Eugen Ulmer, 2001. Pages 89-90. ISBN 3-8001-3131-5 .

- ↑ Amin Shah, De-Zhu Li, Michael Möller, Lian-Ming Gao, Michelle L. Hollingsworth, Mary Gibby (2008): Delimitation of Taxus fuana Nan Li & RR Mill (Taxaceae) based on morphological and molecular data. Taxon 57 (1): 211-222.

- ↑ Da Cheng Hao, BeiLi Huang, Ling Yang (2008): Phylogenetic Relationships of the Genus Taxus inferred from Chloroplast Intergenic Spacer and Nuclear Coding DNA. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 31 (2): 260-265.

- ↑ a b Ulrich Hecker: Trees and bushes. P. 167.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 19.

- ↑ Yew occurrence in Thuringia and problems of yew regeneration ( Memento from June 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ IUCN Red List . Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ↑ Entry at FloraWeb . Retrieved March 17, 2015

- ↑ Taxon Information on wisia.de accessed on November 15, 2015, Appendix 1 to the BArtSchV, “specially protected” within the meaning of Section 7, Paragraph 2, No. 13 c) BNatSchG

- ^ Federal Institute for Food and Agriculture (BLE) . Retrieved on March 17, 2015 Online version of the final report on the yew tree ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 13 MB).

- ↑ Red List of Threatened Species in Switzerland: Ferns and Flowering Plants ( Memento of November 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Online version (PDF; 1 MB).

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 24.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 25 f.

- ↑ a b Andreas Alberts and Peter Mullen: Psychoactive plants, mushrooms and animals , Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-440-08403-5 , p. 202.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 47.

- ↑ Vidensek N. et al .; Taxol content in Bark, Wood, Root, Leaf, Twig, and seedling from several Taxus Species; in Journal of Natural Products, Vol. 53, No 6, pp 1609-1610, Nov-Dec. 1990; Figures in% by weight, average values.

- ↑ a b Michael Brendler: Eibenbaum: No therapeutic antidote against intoxication. In: Medical Tribune. June 28, 2019, accessed July 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 47 f.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 47 and p. 48.

- ↑ Nicolas Schoof, Rainer Luick, Alexandra-Maria Klein: Eating behavior of goats and sheep with yew trees and holly trees - Unexpected experiences from a real laboratory with forest open land grazing near Freiburg i. Br. Nature Conservation and Landscape Planning 49 (12), 2017, p. 397-399 ( researchgate.net ).

- ↑ a b Bostedt, Hartwig, 1938-, Ganter, Martin, 1959-, Hiepe, Theodor, 1929-: Clinic of Sheep and Goat Diseases . Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-13-242281-0 .

- ↑ Toxic Plants Database of the University of Zurich. The information was last accessed on February 24, 2014.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 22.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 26.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 25.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 56.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 57.

- ↑ Hageneder, pp. 51-53.

- ↑ Hageneder, pp. 50-52.

- ↑ Hageneder, pp. 59-62.

- ↑ Schütt, Weisgerber, Schuck, Lang, Stimm, Roloff (ed.): Lexicon of conifers. Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-933203-80-5 , p. 581.

- ↑ Terry Porter: Recognize and identify wood . 2nd Edition. HolzWerken, Hannover 2011, ISBN 978-3-86630-950-0 , p. 243 .

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 71.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 98.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 99 f.

- ↑ a b Hagen Seehase and Ralf Krekeler: The feathered death. The history of the English longbow in the wars of the Middle Ages. Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2001, ISBN 3-9805877-6-2 , p. 34/35.

- ↑ a b Doris Laudert: Myth Tree. BLV Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-405-15350-6 , pp. 98/99.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 110.

- ↑ Doris Laudert: Myth Tree. P. 100 f.

- ↑ Doris Laudert: Myth Tree. P. 96 f.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 49.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 111.

- ↑ Hageneder, p. 48.

- ↑ Maze of yew hedges from Longleat House homepage of the property (English).

- ↑ AuGaLa - Plant Book . 5th edition. tape 1 , 2014.

- ↑ worldbotanical.com .

- ↑ Ibaum . In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm : German Dictionary . Volume 10. Hirzel, Leipzig 1877, Sp. 2016 ( woerterbuchnetz.de , University of Trier).

- ↑ J. Attenberger: The yew trees in the forest of Paterzell / Upper Bavaria . Yearbook Association for the Protection of Alpine Plants and Animals, 29, pp. 61–68, 1964.

- ↑ Stefan Kühn, Bernd Ullrich and Uwe Kühn; Germany's old trees , BLV Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8354-0183-9 , p. 176.

- ↑ Stefan Kühn, Bernd Ullrich and Uwe Kühn; Germany's old trees , BLV Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8354-0183-9 , p. 171.

- ↑ Nature conservation priority areas in the Green Belt . ( Memento of March 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ badische-zeitung.de: District of Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald: The man with the deer , January 28, 2011, accessed on February 13, 2011.

- ↑ a b Badische Bauern Zeitung: “s'Ibetännle” has made itself rare in the forest , July 11, 2009, accessed on February 13, 2011.

- ↑ C. Leuthold: The ecological and plant-sociological position of the yew (Taxus baccata) in Switzerland. Publication by the Geobotanical Institute of the ETH Zurich, Rübel Foundation, issue 67, 1980.

- ↑ hist.unibe.ch ( Memento from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ waldwissen.net ( Memento from June 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ S. Korpel, L. Paule: The yew occurrences in the area of Harmanec, Slovakia. Archiv Naturschutz, Landschaftsf., 16, pp. 123-139, 1976.

- ↑ FJG Mitchell (1990): The history and vegetation dynamics of a yew wood (Taxus baccata L.) in SW Ireland. New Phytologist 115: 573-577.