motivation

Motivation describes the totality of all motives (motives) that lead to readiness to act and the striving of people based on emotional and neural activity for goals or desirable target objects.

The implementation of motives in actions is called volition or implementation competence .

Clarification of basic terms

The term motivation comes from the Latin verb movere (move, drive).

Motivation as goal-oriented behavior was initially explained genetically , i.e. through innate instincts . Examples are the sucking or grasping reflex of a newborn ( early childhood reflex ). In the course of time, around 6000 “instincts” were collected and hierarchically structured. Such typologies alone cannot explain behavior, however. That is why theories followed based on the paradigm of homeostasis and placed need in the foreground (drive-reduction theories). Accordingly, motivation arises from the need to restore a physiological balance. Examples are hunger , thirst, and procreation ; the behavior was thus reduced to the satisfaction of needs. Motivated behavior, however, also exists when physiological needs are already satisfied. Hence, incentive or activation theories have been developed. According to them, motivation results from striving for “optimal activation” (of emotions). These, in turn, are defined as psychophysical reactions that are associated with the activation of central nervous systems . Example: If you ask a mountaineer what motivates him to climb a (strenuous and dangerous) summit, his answer should be: “Simply because the mountain is there”. This is also an example of learned motives.

A (typical) definition of motivation reads: “By signaling whether something is good or bad, dangerous or harmless, and with which general class of behavior (e.g. flight, defense) it should be responded to, they play a central role Role in the motivation of goal-oriented behavior ... While it is controversial whether the perception of physical reaction patterns is a necessary or sufficient condition for the presence of an emotion, there is broad consensus that physiological arousal contributes significantly to the specific quality of experience, the emotions of "cold" Differentiates cognitions. "

Hermann Hobmair also gives detailed information on the definition of emotion in his work. He dealt with the connection between the concepts of emotion and motivation and thereby gained an important insight. Hobmair equates emotions and motivation, since he defines both factors as psychological forces, i.e. the forms of human drive. He describes these forces with the sensitivities of people, but also with their becoming active. He defines emotions as “mental sensitivities, physical states and emotions that influence behavior”. Motivation is “a process of being driven by motives”. Hobmair emphasizes that emotion and motivation are closely related and do not represent different psychological processes, as was often assumed before. In his work he quotes, among others, from Nolting / Paulus, 2002, p. 55: “The same psychological process has ... both a sensitivity side and a drive or target side; and depending on which side you want to emphasize, one speaks of emotion / feeling or motivation. "

Finally, the term “ feeling ” needs to be clarified. This describes the subjectively perceived side of an emotion. For example, someone can feel inferior because they have been triggered by the emotion fear . Emotions usually indicate whether motives have been satisfied or frustrated, and can be felt differently as feelings ("felt").

In summary, these terms can be presented as follows: The activation (central nervous systems) is a prerequisite for all actions. If pleasant or unpleasant sensations are added to this inner excitement, it is an emotion (“I feel good or I feel uncomfortable”). If an emotion is linked to a goal orientation, it is a motive. While a motive is an enduring, latent disposition (readiness to act), the term motivation describes the process of activating (also: updating) a motif. This activation or implementation of motives is also called volition in recent motivational research .

history

Richard Steer's co-authors in 2004 summarized the most significant milestones in the history of motivational theories:

- In ancient Greece, attempts were made to explain human behavior and its motivations with the principle of hedonism . Accordingly, it is in the nature of man to strive for pleasure or pleasure and to avoid discomfort or pain. The Greek philosopher Aristippus , a student of Socrates , saw these subjective sensations as the most important source of knowledge for human behavior.

- A further development of these considerations were the approaches of utilitarianism by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill . With the advent of (scientific) psychology in the 19th century, attempts were made to explain the reasons and causes of behavior with more or less conscious instincts and drives .

- The best known is the theory of Sigmund Freud . He placed the libido as a vital instinct (psychic energy) in the foreground of his concept. This drive (from the id ) directs human perception and behavior depending on the internal and external framework conditions ( ego and superego ).

- William James and William McDougall , contemporaries of Freud, found numerous other instincts or basic needs such as the urge to move, curiosity, striving for harmony, jealousy, saving, curiosity, family, order, play, sex, contact, aggression, achievement or sympathy.

- Because the concepts of Freud and James could not adequately explain human behavior due to a lack of validity , numerous approaches of the learned motives arose in the 1920s, which control behavior through punishment and reward mechanisms. A significant advancement followed in the 1950s by Burrhus Frederic Skinner . Accordingly, through processes of positive and negative reinforcement in the social environment, people learn both certain motives and behaviors that contribute to the satisfaction of these motives. These solidify as schemes or habits and make the behavior explainable and predictable . This is likely to be a major reason why the cognitive behavioral therapy developed from behavioral concepts can empirically prove the greatest success in the treatment of mental disorders.

After the emergence of so-called humanistic psychology at the beginning of the 1950s as the “third force” alongside depth psychology (Freud) and behaviorism (Skinner), two theories emerged that are now considered (scientifically) to have failed due to insufficient (empirical) validity they are well known to this day):

- the theory of motivation by Abraham Maslow and

- The two-factor theory of Frederick Herzberg from the 1960s; it is also to be assigned to the so-called content theories of motivation (same epistemological principle as with Freud, James and McDougall).

Another model of this type was added in 2000 by the US psychologist Steven Reiss (1947-2016) taxonomy . It is

- the "theory of the 16 motives for life" (also called "Reiss profile"). Like other taxonomies, this concept cannot explain or predict behavior and is based on the Barnum effect . Accordingly, the motifs are formulated so vaguely that everyone can choose what applies to them, and after the test they have the feeling that their person has been precisely described.

In the 1960s and 1970s, so-called process theories of motivation emerged. One of the best known is the Porter and Lawler model (see illustration). Accordingly, the personal effort (motivation) depends on the value of the expected reward and on the likelihood of success of the action. Depending on the ability and role perception, the effort leads to certain achievements (results). When external and internal rewards are added, satisfaction increases, which in turn drives new achievements. For a better understanding, it should be emphasized that the model of Porter and Lawler is based on the principle of expected value: Actions arise from desires for certain facts (value beliefs) and beliefs about actions that appear suitable to bring about these wishes (mean beliefs). As a result, people choose among several alternative courses of action those that have the highest expected value.

Since the first publication of this theory, there has been an almost unmanageable amount of research on this topic. A final assessment of this discussion hardly seems possible. Nevertheless, two main research areas can be identified:

- The long-neglected investigation of more or less unconscious emotions, motifs and contents of emotional memory seems to be gaining interest due to advances in imaging processes in brain research. This trend could be supported by further developing the classic projective and introspective methods. The main reason that this area has been largely excluded from research over the past 20 years is that there is no reliable access to the subconscious. You have to take the “detour” via memory, and this is extremely unreliable: After about three years, around 70 percent of the memory content is either lost or (due to accompanying emotions) “falsified” because memories are caused by faulty processes of coding, storage and decoding (re) constructed. Joseph LeDoux therefore speaks of the "seven sins of memory".

- The second research direction focuses on the process of converting motives or intentions into actions within the framework of theories of self-regulation (volition). Concretizations of this concept exist in psychology (see Volition (Psychology) ) and in management science (see Volition (Management) ). The focus is on the question of how one can develop the willpower and certain competencies in order to convert (non-measurable and mostly unconscious) motives into observable and thus measurable actions (see implementation competence ). This gives motivation research a pragmatic turn - towards solving specific human problems in psychology and management. For example, June Tangney and co-authors found that people with above-average self-regulatory or implementation skills suffer less from stress, have higher self-confidence, and are less likely to experience eating disorders or excessive alcohol and drug use; their personal relationships are better and they are more successful professionally.

Sources of motivation

John Barbuto and Richard Scholl distinguish between two intrinsic and three extrinsic sources of motivation. The authors examined the most important theories of motivation since Abraham Maslow (1954) and developed the concept of the “five sources of motivation”. The basis is the approach of the " Big Three " motifs by David McClelland . These motives are the power, belonging, and achievement motives. The graphic opposite illustrates the core idea of McClelland's motivation theory.

At Harvard Medical School , McClelland succeeded in demonstrating that the stimulation of these motives is linked to the release of certain neurotransmitters :

- In the case of the power motive, it's adrenaline and noradrenaline ,

- in the case of the affiliation motif, this is dopamine ,

- when the achievement motive is stimulated, vasopressin and arginine are released .

These neurological processes are evidence of the empirical existence of these motives. Other theories that Barbuto and Scholl have used include the approaches of Frederick Herzberg (1968), Albert Bandura (1986), and Daniel Katz and Robert L. Kahn (1978). Based on these approaches, the authors develop and validate a test (inventory) to measure what they call “sources of motivation” using an independence analysis . It is based on a sample of 156 subjects and a pool of 60 items , the expert judgments validated were (face validity) . The result of the study is a typology of five sources of motivation - two intrinsic and three extrinsic.

Intrinsic motivation describes acting out of inner drives. This includes personal interests, or creative and artistic inclinations and challenges. Intrinsically motivated people get their motivation from the activity or task. In extrinsic motivation, people perform certain services because they expect an advantage (reward) or want to avoid disadvantages (punishment).

The five sources of motivation according to Barbuto and Scholl can be described as follows:

Extrinsic sources

- Instrumental motivation (instrumental motivation) : The behavior of these people is essentially guided by the prospect of tangible benefits or remuneration from outside (extrinsic). For example, the musician wants to earn money, the salesperson sees his current job (or the increase in sales) as an intermediate step on the career ladder to management and the author hopes to write a bestseller or to become famous. This source of motivation is strongly related to the power motive.

- External self concept : In this case, the source of the self-image and the ideal come primarily from the role and expectations of the environment. For example, the striker takes on certain tasks or roles in a team that he wants to master as well as possible. The same applies to the concert pianist as an orchestra member or the ideal manager within the framework of a given corporate culture . The motive of belonging belongs to this source of motivation.

- Internalization of goals (goal internalization) : The people in this group adopt the goals of the organization or company as their own. The manager wants to contribute to the realization of the company's mission, the HR manager wants to make a contribution to making things fairer in the company and the salesperson makes an effort because he is convinced that sales are the most important function in the company, without which the company cannot survive in the market. Here is a combination of belonging and achievement motives at play. The graphic opposite is intended to summarize what has been said.

Intrinsic sources

- Intrinsic process motivation (intrinsic process) : The special characteristic of this motivation is that someone accomplishes a task for its own sake. Example: a musician plays the guitar with enthusiasm, a controller intensively evaluates statistics, an author writes creative articles for Wikipedia or a salesperson engages in engaging discussions with customers simply because they enjoy it. They don't even think about why they're doing this and what benefits or rewards they get for it.

- Internal self concept : The behavior and values of this group of people are based on internal standards and benchmarks. They have internalized an ideal as a guideline for their actions, mostly for reasons that are no longer comprehensible or unconscious. This is the case with controllers as well as musicians, surgeons, salespeople or journalists who want to achieve something according to their ideas. With this source of motivation, the achievement motive is particularly strongly stimulated.

A critical review of the model of the five sources of motivation by John Barbuto and Richard Scholl with an online survey in German-speaking countries with 676 test subjects made it necessary to modify the model. The factor analysis yielded two intrinsic and two extrinsic sources (scales with items as examples). The sources of intrinsic motivation are (1) the task itself; Example item: Being able to delve into an interesting task that I enjoy is more important to me than a high income, status or power and (2) the person; Example item: What matters to me is that I can work on realizing my personal values and goals (vision). The sources of extrinsic motivation are (1) (material) incentives: When in doubt, I decide on a task in which I can improve my income or my professional position and (2) the environment (praise, recognition and appreciation): It is It is particularly important to me that my work is assessed and recognized as very important by my superiors, colleagues or customers.

Variants of intrinsic motivation

Jutta Heckhausen and Heinz Heckhausen suggested the following four options for defining intrinsic motivation:

Intrinsically than justified in the activity

The first use of the term intrinsic motivation in the sense of incentive in the activity itself took place in 1918 at Woodworth . He followed the assumption that only with this incentive could an activity be carried out freely and effectively ("activity running by its own drive", Woodworth, 1918, p. 70). An example of such a structural orientation when anchoring incentives can be found in Karl Bühler (1922). In connection with his subtle developmental psychological observations, he speaks of a "desire to function" and "desire to create" during work.

Intrinsic motivation as a need for self-determination and competence

This definition comes from the self-determination theory of Deci and Ryan, on the basis of which intrinsic motivation is based on competence and self-determination. On this basis, they defined several phases for determining the intrinsic motivation. In the early stages, children are considered intrinsically motivated if they do an activity without receiving a reward for that activity. In the middle phase, Deci and Ryan developed a so-called "Cognitive Evaluation Theory", which sees it as intrinsically motivated when the source of the behavior is seen in oneself. This theory draws on the need for autonomy of deCharms (1968), as well as the need for competence of White (1959) and speaks of an occurring satisfaction value. In the third and final phase, the need for social integration is included, which ultimately led to a »self-determination theory«.

Intrinsic motivation as interest and involvement

This approach to intrinsic motivation is divided into individual and current interests. In the case of individual interest, it is assumed that a learning activity is considered intrinsically motivated if it is experienced in a self-determined manner and the learner can identify with the learning object. The current interest is far more complex. Human behavior is therefore only considered intrinsically motivated if it is motivated by current, anticipated or sought-after experiences of interest. "Interest is defined as a cognitive-affective experience that directs and focuses the attention of the acting person on the activity or task." Interest is then no longer related to the subject, but rather the "action-oriented positive experience during the activity that is currently being experienced, however can also be anticipated and searched for. "

Intrinsic as a correspondence of means and end

The basis for the last definition is the consistency concept by Kruglanski and Heckhausen . This concept says that a goal can be striven for in different ways (equifinality). Likewise, several goals can be pursued through one activity (multifinality). These two approaches to goal attainment weaken intrinsic motivation. For intrinsic motivation, it is crucial that there is always a relationship between activity and goal. This allocation structure and the distinction between specific goals for action ("specific target goals") and more general goals ("abstract purpose goals") originate from a collaboration between Shah and Kruglanski (Shah & Kruglanski, 2000, p. 114). According to these two authors, it is beneficial if the specific action goal is assigned to a more general goal and both goals belong to one activity.

Relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

Intrinsic motivation can be destroyed by extrinsic rewards: If a behavior is controlled almost exclusively by external stimuli (instructions, reward), internal participation decreases, as this undermines the feeling of self-determination . As a result, the self-motivation function , which ensures the experience that the joy of the activity itself arises (flow), can be overridden (so-called corruption or overjustification effect ). However, it is controversial that this effect occurs in general or even at all.

Motivation in relation, expectation and incentive

Approaches to incentive theory

In the incentive theory approaches, the living being is given that it can look ahead and orient its behavior towards the objectives. These target states are to be connected with an affirmation of the behavior. Coupling these incentives with positive or negative affects and the anticipation of these corresponding affects then influence behavior. "Situational stimuli that refer to affectively charged target states are also called incentives."

Since the motivation is based on the pursuit of target states, the incentive, as a situational stimulus, must now be explained more precisely and determines the motivation in two points. These are the possibility that the target state can be recognized in advance and / or that a personal meaning can be grasped in this. The first theory in which this idea of the stimulus was developed in more detail is Lewin's field theory , but here, too, there are different possibilities to consider the theory of the stimulus. Tolman (1951) tried to work out the concepts of expectation and incentive as hypothetical constructs . He states that these act as mediators on a cognitive level, between the situation and the behavior. His main focus here was on clearly showing that a flexible target-oriented behavior could not yet be explained. He also laid the foundations for latent learning and the distinction between motivation and learning. He achieved this assumption mainly by assuming that the affirmation only clarifies whether what has been learned is being carried out and whether this is available in accordance with the predictability of the action in relation to the given incentive. The developments that followed led to a change from the reinforcement theory towards the incentive theory. This development went so far that Mowrer (1960) ascribed everything to the incentives that had been seen so far in the drives .

The following years of research now dealt with further research into incentive theories. As a result, the affirmation was increasingly questioned and replaced. The ultimate result here is a loss of the stimulus-response connection and the inclusion of the new concept of expectation, which replaces it. Bolles (1972) developed two basic types of expectations, the first, the situation-consequence contingencies (SS *) and the second, the reaction-consequence contingencies (RS *), which are the foundations of research to this day. This new definition of type gave rise to the assumption that motivation is to be represented as a function of expectation and value.

Situational parameters of motivation

The behaviorist see learning theories the situation in which a person is, as an outlet for his motivation. They contain the information about the assessment, in which it is clarified how much work is required to achieve the target state. These situations in turn contain stimuli that lead to subjective representations of stimulus and expectation.

The incentive, concepts and approach

“Definition: Incentive is a construct that describes situational stimuli that can stimulate a state of motivation. At the core of this construct are affective reactions that make a fundamental (basic) assessment. "

As can be seen from this definition, a learning history can contribute to a stimulus having an incentive character in which the corresponding object of the situation is connected with an affect. The experiences here are of great significance with regard to the reaction that follows. However, learning alone is not the trigger for such a change, but only a variable that can be replaced ( receptors of the body as the outcome of an experience). The incentive value is related to the value of the object which is perceived as a situational stimulus. As a result, an object with a positive affect also has a positive incentive value and an object with a negative affect also has a negative incentive value. In all of these topics, however, it should be noted that the concept of incentive, just like that of expectation, is viewed as hypothetical among motivational theorists and this differs greatly in the way it is applied between theorists. In all assumptions, however, the incentive is to be understood as action in the energetic sense. It thus attracts the object across spatial and temporal distance. However, the energy of the stimulus is not independent of the person's organic state. According to Toates (1986), these states can act as mediators here. For example , the greater the thirst the organic state dictates, the higher the tolerance for drinkable. However, this does not increase the rating of the drinkable in general. Schneider and Schmalt (1994, p. 16) have made this clear by for them the motives and incentives are closely linked. “Situational incentives characterize the specific motive goals that can be aimed for or avoided. Motives, on the other hand, describe the individually differentiated assessment dispositions for classes of these goals. "

Expectation, concept of research

In addition to the incentive, the expectation is another possibility that is given in the motivational event. It includes “the perceived chance that a certain target state will result from a situation.” However, this expectation is heavily debated in research, as some researchers assume that it cannot be observed from the outside and must therefore be tapped. The main difference between the researchers lies in the fact that some use expectation as the basis for checking what was previously learned.

Incentive and expectation

The idea of the philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) assumed that an explanation of behavior can only be given through a link between value (incentive) and expectation. This link is then also thought of in different dimensions. The unnecessary awareness of the value and / or the expectation is crucial for further research and thus also leads to the explanation that it can be used for animal behavior.

Research fields here are the expectancy-value theory and in parts of Lewin 's field theory .

Content and process models of motivation

Content models can be distinguished from process models. While content models explain human behavior solely on the basis of certain psychological contents, process models also trace behavior back to certain physical processes.

Content models

These models deal with the content, type and effect of motifs. A taxonomy of motives is offered and it is determined according to which regularities which motives determine behavior.

- Humanistic Psychology:

- Hierarchy of Needs by Abraham H. Maslow

- The ERG Theory of Clayton P. Alderfer (Existence - Relatedness - Growth)

- Human-Scale-Development by Manfred A. Max-Neef

- General Psychology:

- Work Psychology:

- The theories X and Y of Douglas McGregor

- The two-factor theory of Frederick Herzberg

- The theory of Mausner & Snyderman

- Economic and non-economic motivators using the example of the company suggestion scheme

Process models

These models try to explain how motivation arises formally and detached from need content and how it affects behavior. The goal of the behavior is undetermined, but the individual wants to maximize the subjectively expected benefit.

- Equilibrium theories (eg. As the Zurich model of social motivation of Norbert Bischof )

- The circulation model Lyman W. Porter and Edward E. Lawler - see section "History"

- The Rubicon model of the action phases by Heinz Heckhausen and Peter M. Gollwitzer

- The Extended Cognitive Motivation Model by Heinz Heckhausen

- The Equity Theory of John Stacey Adams (1965)

- The expectancy theory of Victor Vroom

- The self-assessment model of achievement motivation by Heinz Heckhausen (1972/1975)

- The theory of self-regulation by Bandura (1991)

- The holistic process model of achievement motivation by Guido Breidebach (2012)

- The Motivation Theory of Pritchard and Ashwood (2008)

Applications of motivational theories

Motivation theories play an important role in many areas of life. Examples are:

- Social relationships : Understanding the reasons for the behavior of other people as a basis for joint projects and partnerships.

- Consumer behavior : The question of the basis on which people make consumer decisions is closely linked to the question of buying motives (such as status demonstration or group membership).

- Sales psychology : The assessment of the customer's needs for the targeted adaptation of the offer to the needs of the customer.

- Retail psychology : The linking of management, seller and buyer motivation and the elimination of ( in store ) stressors are increasingly important success factors for modern psychologically oriented retail management.

- Work and organizational psychology : The motivation of employees is often a decisive factor for the productivity of a company or an authority .

- Health psychology : Motivational factors influence preventive health behavior and compliance .

- Clinical Psychology : Motivational factors are used to explain mental disorders , e.g. B. depression , used.

- Educational psychology : The motivation of students and teachers has an impact on school success.

- Sports Psychology : The motivation of athletes has an impact on performance.

- Learning through teaching (LdL): Teaching methods based on needs theory

- Management theory : motivating employees and shaping the corporate culture.

Ethology

Dealing with motivation from the point of view of ethology is dealt with in the article Willingness to act .

Motivation in sport

Athletic achievement motivation is a central variable for explaining athletic performance. It can (in addition to physiological parameters) explain the differences in the performance of athletes.

There are three methods for measuring sport-related motivation in German-speaking countries: AMS Sport, SOQ Sport Orientation Questionnaire and the sport-related performance motivation test SMT. Sports psychological validation studies are available for the latter methods, which show incremental validity via AMS Sport and SOQ (the incremental validity of the SMT is up to ΔR² 0.17 or ΔR² 0.16, depending on the criterion and type of sport). The criteria-related validity of the individual procedures is (uncorrected in each case) R = 0.55 (SMT), R = 0.24 (AMS) and R = 0.41 (SOQ) This means that the lasting benefit of a sports psychological motivation diagnosis goes beyond the use of purely physiological performance predictors documented.

Conclusion: how to motivate people

Practical recommendations for action for motivating people can only be derived from valid, explanatory theories. The neurosciences make a scientific contribution to this. Here motivation is seen as a kind of driving force or energy for goal-oriented behavior. This driving force can be compared to a source of energy. One also speaks of willingness to act. This must first be triggered (activated). A second type of energy must be added to this activating energy. It is necessary to maintain actions until completion (goal achievement). The technical term for this is called volition . In everyday language, this is also called perseverance or willpower .

The "energy sources" are the sources of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation described above, which must first be activated (triggered). This concept by John Barbuto and Richard Scholl is based on the theory that these sources of motivation are related to certain hormones. The authors also proposed an inventory to measure these motives and thus made an important contribution to validation. Her approach is a continuation of David McClelland's theory of the three key motifs (see the graphic above).

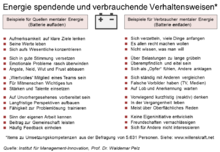

After a motive has been triggered, certain (learnable) skills are necessary so that the energy is maintained until the goal is achieved. According to Roy Baumeister, it is a question of willpower, which he interprets as an 'exhaustible' resource. However, it can be regenerated and thus strengthened through appropriate training - comparable to muscle training. According to an empirical study with 5,631 participants by Waldemar Pelz, this willpower (technical term: volition) can be strengthened by changing certain behavioral habits: reducing energy-consuming habits and expanding energy-giving habits. The graphic opposite shows some examples of such behavioral habits.

Otherwise one can apply the following pragmatic rules of motivation:

- Treat all employees with appreciation and respect

- Agree on clear, realistic goals and provide feedback on the achievement of goals

- Inform employees sufficiently and involve them in decisions

- Say openly what has been decided and where participation is not possible or not desired

- Delegate responsibility as often as possible

- Extend the employees' scope of action as much as possible

- Use the knowledge and experience of the employees

- Bringing responsibility and competencies (powers) in line

- Provide individual advice and support

- Recognize and encourage self-motivation

- Don't overdo it with praise and recognition

- Think forward-looking when mistakes are made instead of looking for the “culprit”

- In the event of critical decisions (withdrawal of competencies, warnings, transfers, terminations, etc.), give those affected the opportunity to save face

- Living values: honesty, fairness, tolerance, reliability, justice, trust

- Be a role model and stand by what you say (also to change your own opinion)

- Always keep promises

- Admit your own mistakes and weaknesses and at the same time clarify the consequences that have been drawn from them

- Show moral courage , especially "upwards"

- Enabling a sense of achievement through challenging tasks

- Showing personal perspectives, but also limits

- Establish transparent and comprehensible criteria for increases in income and for career opportunities

- Promote self-control

See also

- motivation

- Motivational training

- Self-determination theory

- Self-learning skills

- Self management

- Desire

literature

- Joachim Bauer : The principle of humanity - why we cooperate by nature . Heyne 7th edition 2014.

- RF Baumeister et al. (Ed.): Handbook of Self-Regulation . New York 2004.

- RJ Clay: A Validation Study of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Theory . Research Report 1977.

- Edward L. Deci, Richard M. Ryan: The Self-Determination Theory of Motivation and Its Relevance to Education . In: Journal for Pedagogy. No. 39 (1993), pp. 223-239.

- Edward L. Deci, Richard M. Ryan: Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health . In: Canadian Psychology. 49: 182-185 (2008).

- L. Deckers: Motivation - Biological, Psychological, and Environmental . 2nd Edition. Pearson, Boston 2005, ISBN 0-205-40455-3 .

- JP Forgas et al: Psychology of Self-Regulation . New York 2009.

- Jutta Heckhausen; Heinz Heckhausen: Motivation and Action . 4th edition Berlin, 2010.

- Heinz Heckhausen , J. Heckhausen: Motivation and Action . Springer, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-540-25461-7 .

- Hermann Hobmair (Ed.): Pedagogy, psychology for the professional upper level . Volume 1. Bildungsverlag EINS, Troisdorf 1998, ISBN 3-8237-5025-9 , pp. 168-201

- Hugo Kehr: Motivation and Volition . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-8017-1821-2 .

- J. Kuhl: Motivation and Personality. Interactions of Mental Systems . Hogrefe, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-8017-1307-5 .

- C.-H. Lammers: Emotional Psychotherapy . Stuttgart 2007.

- EA Locke, GP Latham: What Should We Do About Motivation Theory? Six Recommendations for the Twenty-First Century . In: Academy of Management Review. Volume 29, No. 3, 2004.

- DA Ondrack: Defense Mechanisms and the Herzberg Theory: An Alternate Test . In: Academy of Management Review. Volume 17 (1974)

- M. McKay et al: thoughts and feelings, techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy . Paderborn 2009.

- W. Mischel, O. Ayduk: Willpower in a Cognitive-Affective Processing System . In: RF Baumeister et al. (Ed.): Psychology of Self-Regulation . New York 2004.

- W. Pelz: Competent leadership . Wiesbaden 2004.

- RD Pritchard, EL Ashwood: Managing Motivation: A Manager's Guide to Diagnosing and Improving Motivation . Routledge, New York 2008, ISBN 978-1-84169-789-5 .

- M. Prochaska: Achievement Motivation - Methods, Social Desirability and the Construct . Lang, Frankfurt 1998.

- F. Rheinberg: Motivation. 6th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-019588-3 .

- H. Schuler , M. Prochaska: Development and construct validation of a job-related achievement motivation test . In: Diagnostica. Volume 46, No. 2, 2000, pp. 61-72.

- RM Steers: The Future of Work Motivation Theory . In: Academy of Management Review. Volume 29, No. 3, 2004, pp. 379-387.

- JP Tangney, RF Baumeister, AL Boone: High Self-Regulation Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success . In: Journal of Personality. Volume 72, No. 2, 2004.

- TD Wall et al .: Herzberg's Two-Factor-Theory of Job Attitudes: A critical Evaluation And Some Fresh Evidence . In: Industrial Relations Journal. Volume 1, No. 3, 2007.

- H.-U. Wittchen, J. Hoyer (Ed.): Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2nd Edition. Berlin 2011.

Web links

Single receipts

- ^ Pschyrembel: Clinical Dictionary. 259th edition. Berlin 2002, p. 1087.

- ↑ Joseph Ledoux: The network of personality. Düsseldorf 2006, p. 338 f. and Mark Bear, Barry Connors, Michael Paradiso: Neurosciences. 3. Edition. Heidelberg 2009, p. 571 f.

- ^ Klaus Grave: Neuropsychotherapy. Göttingen 2004, p. 116 and Frederick Kanfer: Self-regulation and behavior. In: H. Heckausen u. a .: Beyond the Rubicon: The will in the human sciences. P. 276 f.

- ↑ Duden, dictionary of origin. 1989.

- ↑ David. G. Myers: Psychology. 9th edition. New York 2010, p. 444 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wittchen, Jürgen Hoyer (Ed.): Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy . 2nd Edition. Berlin / Heidelberg 2011, p. 131.

- ↑ David. G. Myers: Psychology. 9th edition. New York 2010, p. 446 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wittchen, Jürgen Hoyer (Ed.): Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy . 2nd Edition. Berlin / Heidelberg 2011, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Hermann Hobmair (Ed.): Pedagogy, psychology for the professional upper level . Volume 1. Bildungsverlag EINS, Troisdorf 1998, ISBN 3-8237-5025-9 , pp. 168-201.

- ↑ C.-H. Lammers: Emotional Psychotherapy . Stuttgart 2007, p. 33 ff.

- ↑ Werner Kroeber-Riel u. a .: consumer behavior . 9th edition. Munich 2009, p. 60 ff.

- ^ Joseph P. Forgas, Roy F. Baumeister, Dianne M. Tice: Psychology of Self-Regulation . Psychology Press, 2009.

- ↑ RM Steers: The Future of Work Motivation Theory . In: Academy of Management Review. Vol. 19 (2004), No. 3.

- ^ W. McDougall: An Introduction to Social Psychology . Boston 1921.

- ^ DG Myers: Psychology . New York 2004.

-

^ RJ Clay: A Validation Study of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Theory . Research Report 1977.

DA Ondrack: Defense Mechanisms and the Herzberg Theory: An Alternate Test . In: Academy of Management Journal. Vol. 17 (1974); TD Wall et al .: Herzberg's Two-Factor-Theory of Job Attitudes: A critical Evaluation And Some Fresh Evidence . In: Industrial Relations Journal. Vol. 1 (2007), No. 3. - ↑ Steven Reiss: Who Am I? New York 2000.

-

↑ Bärbel Schwertfeger : Personality test - wanted: The perfect colleague. In: Zeit Online . July 11, 2012, accessed on August 3, 2019 : "Companies want to be able to assess their employees better - with the help of questionable personality tests." Eva Buchhorn: Transparent candidates: employers screen applicants to the limit of the legal - 2nd part: When recruitment mutates into a detective game . In: Manager-Magazin.de. October 7, 2011, accessed August 3, 2019 . Waldemar Pelz: Reiss Profile: Critique of the “theory” of the 16 motives for life. Discussion paper, Technische Hochschule Mittelhessen , May 2017 ( management-innovation.com PDF: 472 kB, 9 pages).

- ^ W. Pelz: Competent leadership . Wiesbaden 2004.

- ↑ R. Eckert u. a .: Psychotherapy . 3. Edition. Heidelberg 2007.

- ^ EA Locke, GP Latham: What Should We Do About Motivation Theory? Six Recommendations for the Twenty-First Century . In: Academy of Management Review. Vol. 29 (2004), No. 3, p. 389 f.

- ^ EA Locke, GP Latham: What Should We Do About Motivation Theory? Six Recommendations for the Twenty-First Century . In: Academy of Management Review. Vol. 29 (2004), No. 3, p. 395 f.

- ↑ J. Ledoux: The network of personality. Munich 2006.

- ↑ JP Forgas et al.: Psychology of Self-Regulation. New York 2009.

- ↑ W. Mischel, O. Ayduk: Will Power in a Cognitive-Affective Processing System . In: RF Baumeister et al. (Ed.): Psychology of Self-Regulation. New York 2004.

- ↑ RF Baumeister et al. (Ed.): Psychology of Self-Regulation . New York 2004.

- ↑ JP Tangney, RF Baumeister, AL Boone: High Self-Regulation Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success . In: Journal of Personality. Vol. 72 (2004), No. 2.

- ↑ a b c d e f John E. Barbuto, Richard W. Scholl: Motivation Sources Inventory: Development and Validation of New Scales to Measure an Integrative Taxonomy of Motivation . In: Psychological Reports . tape 82 , no. 3 , June 1, 1998, ISSN 0033-2941 , p. 1011-1022 , doi : 10.2466 / pr0.1998.82.3.1011 ( sagepub.com [accessed April 4, 2017]).

- ^ DC McClelland: Human motivation . Cambridge 1987.

- ^ DC McClelland, R. Davidson, C. Saron, E. Floor: The need for power, brain norepinephrine turnover and learning. In: Biological psychology. Volume 10, Number 2, March 1980, pp. 93-102, PMID 7437489 .

- ↑ David C. McClelland, Vandana Patel, Deborah Stier, Don Brown: The relationship of affiliative arousal to dopamine release. In: Motivation and Emotion. 11, 1987, p. 51, doi : 10.1007 / BF00992213 .

- ↑ David C. McClelland: Achievement motivation in relation to achievement-related recall, performance, and urine flow, a marker associated with the release of vasopressin. In: Motivation and Emotion. 19, 1995, p. 59, doi : 10.1007 / BF02260672 .

- ↑ Brockhaus Psychology . Mannheim 2009, p. 277.

- ^ Myers, D .: Psychology . 10th edition. New York: Worth Publishers 2013, p. 289.

- ^ DG Myers: Psychology. New York 2004, p. 330 f.

- ↑ Based on the English-language questionnaire by JE Barbuto: Motivation and transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership: a test of antecendents. In: Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2005, Vol. 11, No. 4 and the German version of w. Fur test of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

- ↑ Pelz, W .: Test of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

- ↑ a b c d Jutta Heckhausen; Heinz Heckhausen: Motivation and Action . 4th edition Berlin, 2010.

- ↑ Edward L. Deci, Richard M. Ryan: The self-determination theory of motivation and its importance for pedagogy. P. 226.

- ^ Judy Cameron, Katherine M. Banko, W. David Pierce: Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation. The myth continues . In: The Behavior Analyst . tape 24 , no. 1 , 2001, p. 1-44 . , PMC 2731358 (free full text, PDF).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jutta Heckhausen, Heinz Heckhausen (Ed.): Motivation and action . 4th edition. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-642-12692-5 , pp. 105 ff .

- ^ Peter Koblank: Motivation in the BVW. Part 1: Importance of economic and non-economic motivators. EUREKA impulse 2/2012, DNB 1027070981 .

- ↑ a b Andreas Frintrup, Heinz Schuler : SMT - sport-related performance motivation test . Publisher Hogrefe, 2007

- ↑ Jürgen Beckmann, Anne-Marie Elbe: Practice of sports psychology: Mental training in competitive and competitive sports . Verlag Spitta, 2nd edition 2011, ISBN 978-3941964198

- ↑ Federal Institute for Sport Science (Ed.): Questionnaire on performance orientation in sport: Sport Orientation Questionnaire (SOQ) , Sportverlag Strauss, 2009, ISBN 978-3868844931

- ↑ Annika Olofsson, Andreas Frintrup, Heinz Schuler: Construct and criteria validation of the sport-related achievement motivation test SMT . Zeitschrift für Sportpsychologie No. 15/2008, pp. 33-44.

- ↑ Note: R can take values from 0.00 to 1.00, with 0.00 indicating no correlation and 1.00 indicating a perfect correlation.

- ↑ For the scientific-theoretical justification see: Karl Popper: Logic of Research . 8th edition. Tübingen 1984 and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker: Structure of Physics . Munich 1985.

- ↑ Mark Bear, Barry Connors, Michael Paradiso: Neurosciences . 3. Edition. Heidelberg 2009, p. 570.

- ↑ Joseph Ledoux: The network of personality . Munich 2006, p. 312 ff. And Pschyrembel: Clinical dictionary. 261st edition. 2007.

- ↑ P. Haggard: Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will. In: Nature reviews. Neuroscience. Volume 9, Number 12, December 2008, pp. 934-946, ISSN 1471-0048 . doi : 10.1038 / nrn2497 . PMID 19020512 . (Review) and Rick Hoyle: Handbook of Personality and Self-Regulation . Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- ^ John Barbuto, Richard Scholl: Motivation sources inventory: development and validation of new scales to measure an integrative taxonomy of motivation. In: Psychological Reports. 1998, Vol. 82, pp. 1011-1022.

- ↑ On the McClelland concept see: Stephen Robbins et al: Fundamentals of Management. 7th edition. Pearson, New Jersey 2011, p. 296.

- ^ Roy Baumeister, John Tierney: Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength . The Penguin Press, New York 2011.

- ↑ Further information with research report including the publications specified there. Willpower (volition) - the implementation skills

- ↑ Waldemar Pelz: Leading competently: Communicating effectively, motivating employees. Wiesbaden, Gabler Verlag, 2004, pp. 119-120.