Peter Schro

Peter Schro (* around 1485 in Mainz ; † before August 18, 1544 there ), also written Schrör, Schror and Schrot, was a German sculptor between the late Gothic and early Renaissance . It was documented in Mainz between 1522 and 1542/44.

Life

Identification of the name

For a long time, the master of Halle Cathedral remained anonymous. The ultimate identification of his name can be understood as an art-historical crime story that spans almost 130 years. In retrospect, the following milestones emerge.

Searching for traces in the 19th century

- Gustav Schönermark (1886): Comprehensive representation of the figural and architectural details of Hallesches Doms. Incorrectly assumes that the cathedral in Halle was a new building that was completed between 1520 and 1523. Finds out that the material used in the sculptures is not sandstone, but a volcanic product, a trass rock from the Rhine. He assigns this material to the large and, by mistake, also to the small consecration tablet. The light, gray-yellow stone could be worked with a knife, so that swords, staffs and string decorations were made floating freely over long distances. Sees the master of Halle as "the first artist of the modern age", who has outgrown the Gothic and makes extensive use of the new elements of the Renaissance (pearl sticks, acanthus leaves, palmettes, etc.). He therefore suspects the master is traveling to Italy and Spain and has no doubt that all the works of art in the cathedral come from one source. Published detailed drawings, etc. a. also to the console figure under St. Mauritius, in which he suspects a self-portrait of the master.

- Paul Redlich (1900): Proofs through thoroughly researched archival findings on Halle Cathedral that the old Dominican church was converted into the new monastery of Cardinal Albrechts . For the first time it is assumed that there must have been a school connection between the sculptors and stonemasons involved (the Magdeburg cathedral hut is assumed). The work can only be completed in the short period of six years according to the drafts and under the supervision of a master and several journeymen. Even if the master did not have to have been to Italy due to the Renaissance elements, he at least knew the large southern German trading cities. The pillar statues were undoubtedly among the best that German sculpture did at that time.

Searching for traces in the 20th century

- Paul Kautzsch (1911): Formulated the emergency name “Master of the Halle Cathedral Sculptures” for the unknown artist from the Halle pillar cycle. Two lanes lead from Halle to Mainz. The consistent use of Rhenish tuff for the Halle figures refers to the proximity of the Rhine. And Cardinal Albrecht would also rather bring a master to Halle whom he knew from Mainz on the Rhine. The style-critical comparison locates the Halle master in the school of Hans Backoffens († 1519), which can be proven in Mainz . The important portrait heads of the pillar figures, which must be based on model studies, are emphasized. The work can only have been created in six years with the support of the master by several journeymen. At the same time as Kautzsch's dissertation (1909) and independently of one another, Dehio (1909) also assigned the Halle master to the Backoffen School.

- Ernst Kähler (1955/56): The figure cycle aims to express a certain meaning of its time rather than an artistic statement. What is essential is u. a. the figure of Erasmus . Cardinal Albrecht's intense admiration for Erasmus and his humanism is expressed in special peculiarities (Erasmus appears twice as a pillar and canopy figure, quotation from Erasmus' Greek translation of the Bible, highlighted on Paul's sleeve). A complete analysis of the meaning of the existing and missing attributes of all figures is presented (see tables of pillar and canopy figures). The Latin inscriptions on the garment hems can be assigned to a specific type of liturgical prayers. The prayer verses of this medieval model, the "Litania maior", determine the order and grouping of the pillar figures. The pulpit is interpreted as an expression of the “omnis sermo Dei”, the whole word of God, leading to a reform-friendly, Catholic humanism.

- Heinz Wolf (1957): The sculptural works in Halle Cathedral were created by three participating workshops: Bastian Bindersche Dombauhütte, pillar figure workshop and pulpit workshop by Ulrich Creutz. Later, the authorship of Ulrich Creutz was questioned again by Nickel (1991) and Bischoff (2006), since the Hallesche Domkanzel is “more lively and of higher quality” than the works used by Wolf (1957) for comparison. Two artistic epochs with their very specific characteristics manifest themselves in the pillar figures (vestments are from the late Gothic period and have a mannerist nuance, heads and hands correspond to the new Renaissance conception). After the dissolution of the Backoffen School in 1519, a "trunk workshop" is adopted, which was run by his students and remained in Mainz. At least two groups of people are involved in the pillar and canopy figures. The first is the master, who was responsible for all the designs of the large figures and the production of the Christ figure. Other people in this group were responsible for the execution of the remaining large figures, all of the canopy housings, the canopy figures of Ecclesia and Madonna and the consoles of Christ, Peter, Mauritius and Magdalena. The two consecration tablets were also executed by this group. All other canopy figures and consoles are likely to have been created by a second group of people who did not have the same artistic quality. The inscriptions on the garment hems are completely determined.

- Hans Volkmann (1963): While Wolf (1957) certainly ascribes the small consecration plaque in Hallesches Dom to the pillar figure workshop, this is corrected here in order to assign it to the work of Loy Hering . No attempt is made to ascribe the large consecration tablet to a sculptor, although it is mistakenly placed in the vicinity of the pulpit master. In each case, a master is assumed who had fully internalized the renaissance feeling of the south.

- Irnfriede Lühmann-Schmid (1975, 1976/77): Your work fundamentally changes the situation, since you can identify Peter Schro as the master of the Halle pillar figures and other works. The evaluation of documentary mentions in Mainz shows some evidence of the name Peter Schro in the files from the period from 1522 to 1544, which refer to payments by Cardinal Albrecht. It follows that he was called "peter schro Bilthauer" and that his date of death can be found around the year 1545. Since the documents do not provide any information about the works created by him, the works of the Backoffen School are examined, within which three works with the signature "P · S" can be identified ( epitaph Walter von Reiffenberg, grave plate Heinrich Meyerspach and grave stone Kuno von Walbrunn). The remaining oeuvre of Peter Schro is made accessible step by step through style-critical comparisons and classified in a chronology of his creative phases (Lühmann-Schmid). In addition to the master foreman, Peter Schro, three journeymen and other employees are accepted for the execution of the work in the cathedral in Halle. Finally, his artistic charisma on other masters of his time (Meister Jacob, Meister Wendel and, to a certain extent, Ulrich Creutz) can be derived from this. The associated school education is conveyed and passed on through his son (perhaps also nephew), Dietrich Schro, and through Hans Wagner. Its regional and supraregional importance is indisputable.

Searching for traces in the 21st century

- Ursula Thiel (2006): The signature of Peter Schro recognized by Lühmann-Schmid on the epitaph of Walter von Reiffenberg cannot be confirmed and seems to have come about by chance. Peter Schro must have had his own workshop in Mainz during Backoffen's lifetime († 1519). He will not only have been responsible for the design and execution of the individual sculptures, but also for the overall conception of the cycle. While the other works of Schro are also controversially discussed with regard to their authorship, the pillar figure cycle can certainly be assigned to his person and workshop.

- Ursula Thiel (2014): Basic work on Dietrich Schro (after. 1542 / 44–1572 / 73), the son (or nephew) of Peter Schro, who, unlike Peter Schro, had been known for a long time. Also includes the critical review of all research results and sources known about Peter Schro. Despite two corrections to the previously known documentary mentions of Peter Schro, the identification of Peter Bildhauer with Peter Schro is considered very likely. Peter Schro's fortune can be calculated for 1540 and amounts to a total of 350 guilders. His death can be narrowed down between the beginning of 1542 and the summer of 1544, since a Mainz council minutes from August 18, 1544 mentions his widow. Presumably Peter Schro was the owner of the house "under the Schmidten called the Badstube" in Mainz - the street runs parallel to today's Rheinstraße between Holzstraße and Kapellhofgasse, as the copy from a Borgationsbuch from 1541-48 reports. No signed work is known from the last twenty years of Peter Schro's life. All sources suggest that Dietrich Schro took over his father's sculpture workshop after the death of his father. Before that, he will have worked as a journeyman in his father's workshop. Since there is evidence of Dietrich Schro's wife Elisabeth and four children - Heinrich, Johann (Hans), Anna and Maria - in the sources, these are close relatives of Peter Schro.

Life dates

Documented sources and signatures

In the city archives of Würzburg and Mainz, Lühmann-Schmid (1975) found several documentary evidence about Peter Schro. After some corrections by Thiel (2014), the secured information remains as follows:

- 1522: Chamber accounts of Albrecht von Brandenburg list Peter Bildhauer as a recipient of service money from the electoral court (StA Würzburg): "Quitantz Peter Bildhawer vber VIII guld (en) dat (um) / Anno 1522"

- 1541/12/20 beg. - Beginning of 1542: Four registers for the land tax of the city of Mainz in the second goal, 1541–1542. Quarthefte I – IV (StA Würzburg): In the lists "Peter schrot bilthaver", "Peter Bildthawer", "peter Bildthawer" and "peter schro Bildthawer" are among the members of the goldsmiths' guild each with payments of 1 guilder and 18 Albus recorded. Apart from Peter Schro, no other sculptor is listed; he appears in the quartos I – IV in 17th position with the names listed. In the IV. Land tax list of 1542, "peter schro Bildthawer" from the "Goltschmidt / zufft" is mentioned for the last time with a payment of 1 gulden and 1 Albus (StA Würzburg, list of members of the goldsmiths' guild).

- 1544/08/18: Mention of the widow of Peter Bildhauer in a complaint in the minutes of the council of the city of Mainz (StA Würzburg): "Idem constituted Anthonj against: Peter / bildhawers wittfraw" In this respect Peter Schro must have died on August 18, 1544.

- before 1830: Karl Anton Schaab's (1761–1855) excerpt from the no longer preserved Mainz borrowing book from 1541–1548 (Sta Mainz, Schaab estate): House under the Schmidten (Schlossergass) the bathing room named_ / stost behind and forn on 2nd common Streets / Peter Schrör Sculptor. 1542. Ux. (Or) Kunigund. He died. 1545. The entry “He died. 1545. ” is confusing, because in August 1544 Peter Schro had already died. Schlossergasse in Mainz still exists today. Thiel (2014) locates the Schlossergasse region around the "Badstube" between Kappelhofgasse and Holzstrasse - i.e. here: 49 ° 59 ′ 49.8 ″ N , 8 ° 16 ′ 39.7 ″ E

Lühmann-Schmid (1975) recognizes three works by Peter Schro as inscribed works, in which she could find corresponding signatures:

- Epitaph of Walter von Reiffenberg († October 30, 1517), Kronberg, Protestant parish church.

- Grave plate of Heinrich Meyerspach († 1520), Frankfurt-Höchst, Justinuskirche.

- Gravestone of Kuno von Walbrunn († 1522), Partenheim, Protestant parish church.

After checking the work again, Thiel (2014) discards the signature from 1517 on Walter von Reiffenberg's epitaph because it has hardly anything to do with the other two signatures and seems to have come about by chance. Nevertheless, she continues to attribute the epitaph of Walter von Reiffenberg to Peter Schro.

Biographical information

Until well beyond the first half of the 20th century, art history talked about a student of Hans Backoffen when it wanted to refer to the importance of the “master of Halle cathedral sculptures”. It was recognized early on that the master from Halle went beyond Backoffen and combined his “greatness of perception with deeper feeling”. On the other hand, the namelessness of the master for a long time impaired interest in in-depth academic study of this artist.

Even if the concrete living conditions are unclear, the following life stages can be recorded based on Lühmann-Schmid "as a suggestion for the reconstruction of Peter Schro's presumed life course". The sources do not give an exact year of birth for Peter Schro. He is believed to have been born in a Mainz family around 1490. After training with the well-known sculptor Hans Backoffen in Mainz, he may have spent his mandatory years of travel from around 1506 to 1512 in the vicinity of Würzburg and Swabia. Although there is no evidence of this, his wealth of forms suggests that he got to know Tilman Riemenschneider's workshop in Würzburg as a journeyman or later as a master . In particular, the dreamy, lyrical attitude of many of his works is more reminiscent of Riemenschneider than of Backoffen's dramatic imagery. In Würzburg he could have come into contact with the northern Italian architectural and decorative elements of the early Renaissance.

Probably returned to Mainz around 1515, he will have settled there and acquired his civil and master rights. Peter Schro was an artistically working sculptor and therefore belonged to the goldsmith's guild in Mainz (in contrast, the stonemasons were members of the workers' guild). Whether he temporarily worked in a creative community with Hans Backoffen or immediately founded his own master workshop can no longer be reconstructed. What is certain is that he created his first independent sculptures since 1516 (consecration plaque of the Magdalenen Chapel in the Moritzburg in Halle) and worked as an independent master from that point on.

For the period between 1510 and 1519, Goeltzer (1991) considers it possible that Backoffen “only operated as an entrepreneur in the period in question” for reasons of age. However, the question of whether Peter Schro cooperated with the obsolete Backoffen as a subcontractor in order to take over his workshop in 1519 can no longer be answered with certainty. In any case, Lühmann-Schmid adopts the customary custom that the workshop was passed on to the master craftsman after the master's death or that the master craftsman became the successor through the marriage of the master’s daughter (?).

It can be considered certain that Peter Schro will succeed him at the court as a "servant" after his death (1519). In the period from 1522–1544 he had his workshop in Mainz, which received court orders from Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg. During his activity in Mainz he must have been the only self-employed and wealthy sculptor in the city, as only his name is mentioned in the tax files. In terms of style, Peter Schro underwent a change in the decade between 1520 and 1530 from the latest Gothic to the earliest Renaissance, with clear echoes of early Mannerist elements. He probably spent the last years of his life in a house on Schlossergasse ⊙ in Mainz.

Peter Schro was married and founded a family dynasty as a stone cutter, which his son, Dietrich Schro (after. 1542 / 44–1572 / 73), continued as a stone sculptor and medal cutter. His son Heinrich Schro (post. 1573–1595) also continued the family tradition as a sculptor, while his brother Johann (Hans) Schro (post. 1577–1594 / 95) possibly worked as a coin cutter. Dietrich Schro was married to his wife Elisabeth and, in addition to their two sons, had daughters Anna and Maria. From the sources it can be concluded that Heinrich Schro had a son Johannes. Johannes Schro, son of Heinrich and great-grandson of Peter Schro, baptized in 1586, died no later than nine years after his baptism.

“Just over two years after his (last) mention in the Mainz land tax lists of 1542, Peter Schro had already died on August 18, 1544. Because the corresponding entry in the council minutes of the city of Mainz speaks of ›Peter Hildhawers wittfraw‹. The time of his death can thus be narrowed down between the beginning of 1542 and August 18, 1544. "

In the troubled intervening times between the Reformation and the Peasant Wars, Peter Schro found a “successful synthesis of tradition, contemporary style and his own language” and an “astonishing complexity of pictorial form and message” in sculpture on the Middle Rhine.

Creative phases

Lühmann-Schmid differentiates between the following phases in Peter Schro's work:

- Early works from around 1516–1518

- Works from the period 1518–1520 that crossed the boundaries of the late Gothic

- Works from the years 1521–1523

- Sculptures for Cardinal Albrecht's residence in Hallesches Dom

- The work of the maturity period in the Mainz area

- The work of the late creative phase from around 1530–1540

The categories "inscribed works" and "wood sculptures" that she also named are not listed, as these are not phases that can be directly separated in time.

Pivot back-open school

Hans Backoffen was a sculptor (* 1460 Sulzbach, † September 21, 1519 Mainz), who was probably trained by Tilman Riemenschneider in Würzburg. In 1500 he is proven as a citizen in Mainz with his own workshop and he also belonged to the guild of goldsmiths. He was married to Catharina Fustin from the renowned Fust family of goldsmiths in Mainz. Under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg he was a respected court sculptor in the archbishop's service, just like Matthias Grünewald had this privilege as a painter. In 1515 Albrecht gave him tax exemption for material and transport of the sculptures, and in 1517 further privileges and commendations. He was a member of the brotherhood of St. Stephen's Foundation. His work is mainly done in stone (Eiffel Tufa, sandstone). Wood carvings by his hand are not reliably verifiable, but are attributed to his artistic environment. "Alongside Hans Leinberger , he is considered to be the most important representative of the so-called late Gothic Baroque in the Middle Rhine region , whose school works and also works by independent successors are widespread in Germany." were determinable. In this respect, one saw in Hans Backoffen the outstanding sculptor of the late Gothic in the Mainz area.

While Backoffen was still assigned a broad oeuvre in the 19th century, Kautzsch (1911) summarized the knowledge about his work and groups the works. He differentiates between handwritten works, works by independent students (to which the "Master of Hallesche Domskulpturen" belongs) and wood sculptures that were not personally attributable to him. The scope of the handwritten work Backoffens is significantly restricted, so that 13 works (crucifixion groups, grave monuments, baptismal font) remain, which are personally credited to him. In the meantime, doubts about the role of Hans Backoffen as the leading sculptor of the late Middle Ages in the Middle Rhine area are increasing. In order to investigate this question more intensively, the extensive work by Goeltzer (1989/90 and 1991) is presented. After looking through the archive documents about Hans Backoffen, he has to judge that, contrary to the apparent clarity, little is known about the life of the master. The eleven surviving sources, which only cover a period of ten years, are very heterogeneous because they differ in their value. As a result, he only has 8 works that can be clearly assigned to him. Since it is precisely the artistically high-quality works that now had to be attributed to other stone and wood sculptors, it is assessed in summary that Hans Backoffen "was definitely an accomplished, but never the outstanding sculptor".

Goeltzer (1991) consequently argues that Peter Schro, as a student and journeyman of Backoffen's, and in a creative community with him, can be excluded, since he signed his works on his own responsibility while Backofen was still alive (see his Meyerspach signature from 1517/18 before Backoffen's death 1519). A journeyman or even a student would never have been allowed to do this for reasons of guild law. In this respect, Schro's performance is not only derived from the Backoffen factory or the "Backoffen School", but rather establishes an oeuvre as an independent master who works parallel to Backoffen. He may have been a student at Backoffens at an earlier point in time, and at times, but justified a Baked completely different conception of art in terms of figure design, clothing and folds.

More recent research leads to the next changes in assignments and melts Oven's oeuvres further. Wilhelmy (2001) only states one safe work in ruinous condition, which can be ascribed to him. "... if there are no new attributions secured by sources, Hans Backoffen will again become what many of his medieval sculptor colleagues are for us to this day: artists without a secured oeuvre."

Because of the parallelism of their master workshops in Mainz, there were personal relationships between Backoffen and Peter Schro. On the one hand, artistic parallels between Backoffen and Schro are already discernible, because both works are based on Gothic. On the other hand, they were based in Mainz at the same time as independent masters who, as Goeltzer (1989/90) suspected, could have been in a client-contractor relationship and therefore must have known each other well. In addition, one must assume a close connection between the two masters, because Peter Schro executed Hans Backoffen's memorial (crucifixion group in the St. Ignaz cemetery in Mainz ).

Cardinal Albrecht as commissioner of the pillar figures

At the age of 24, Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg, the prince's son from the House of Hohenzollern, who had become an orphan at the age of 11, became the most powerful church prince in Germany (bishop or archbishop of Magdeburg and Mainz, office of imperial arch-chancellor). In his area of influence he promoted humanistic sciences and Renaissance art, carried out university and administrative reforms and developed his cities into cultural and art centers with a wide range. It must be taken into account that his territory was filled with the clashes of the peasant wars of 1525 and was affected by religious disputes, poor harvests and the arbitrariness of the sovereigns. The theological problems of his time were discussed by the humanists around Erasmus von Rotterdam and Agricola , as well as discussed in the assemblies of the Franconian-Swabian and Thuringian peasant groups. Luther threatened the Catholic power with his reformatory standpoints. From these social and theological framework conditions are u. a. to explain the plans to Cardinal Albrecht for his Neues Stift. Merkel (2004) also refers to a comprehensive phenomenon of medieval man, his fear of the hereafter. For centuries it represented the engine for the establishment of pious foundations, churches, altars, hospitals and grave monuments. The entire New Abbey, and within it the expensive reliquary collection of Cardinal Albrecht, served both the salvation of the believers and his own afterlife .

In order to achieve this, Albrecht oriented himself towards the Italian patrons of the arts and was a patron and benefactor who gathered the best artists of his time around him and rewarded them generously. The painters Matthias Grünewald , Lucas Cranach the Elder worked for him . Ä. , Hans Baldung Grien , Albrecht Dürer , Simon Franck , the Vischer foundry family , the illuminator Nikolaus Glockendon , the goldsmith Hans Huiuff d. Ä., The engraver Sebald Beham , the sculptors Loy Hering and Peter Schro and finally the talented builders Bastian Binder and Andreas Günther. Albrecht used particularly lavish funds to increase his reliquary treasure and to furnish it with valuable containers and shrines. “According to the inventory from 1525 and other sources, the New Abbey owned 142 paintings as part of the Saints and Passions cycle and perhaps about 40 more that were spread across the rest of the room. For the most part it was a multi-winged retable that adorned most of the 16 altars. With a few exceptions, these paintings formed a thematically coherent and optically uniform cycle by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Ä. The most impressive reliquary of the New Abbey was Saint Mauritius, whose gold-plated solid silver armor was richly set with precious stones and pearls. There is much to suggest that the richly decorated armor with which the silver figure was clad was an original splendid armor from Charles V. The emperor shows the great favor that he wanted to show his chancellor. He had the precious works of art summarized twice in richly illustrated inventories (Hallesches Heiltumbuch from 1520 and the second Heiltumbuch, the Aschaffenburg Codex from 1526). Since the artworks of the New Abbey and their healing books offered the artists and sculptors of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg a sought-after model, Albrecht's collections had a direct impact on the development of Central German Renaissance architecture and art.

Although the love of virtue was one of Cardinal Albrecht's leitmotifs, several mistresses are said to have been his. There is evidence that Leys Schütz was the Cardinal's consort and, also, backed up by sources, Agnes Pless took over this role after her death . Ursula Rehdinger is also said to have been a lover of Albrecht and has significance for various legends (cf. “Snow White Coffin” and “Love Pain Heart” in Aschaffenburg). However, it cannot be historically proven. In addition, there are the names of several concubines, which are historically only poorly verifiable, but in their entirety confirm a certain tendency of the cardinal to "veneris".

Albrecht could not stop the rise of Protestantism in Halle . As early as 1539 there were only a few Catholics left in the Halle city council. "Martin Luther's diatribes against Cardinal Albrecht also contributed to undermining the authority of the Cardinal." In his crude verbal abuse, he described Albrecht as "Scheisbishop" and "Satan of Mainz". "Between May 22, 1514, when he moved into Halle, and February 21, 1541, when he finally left the city almost 27 years later, Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg made Halle one of the most important art centers of the Holy Roman Empire." A Catholic humanist, a patron of the arts and power man, a lover of women and a church prince who was deeply interested in the salvation of the soul, the citizens of Halle and himself, had failed.

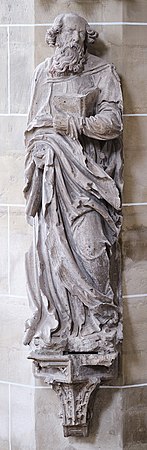

Art-historical specifics using the example of the pillar figures

Characteristic is the gradual replacement of the linearity of the 15th century in favor of a new conception of materiality and space, illustrated in the jagged surface and the bizarre twisted folds. Peter Schro's sculpture stands at the end of the late Gothic period, is still attached to it, but at the same time opens the door to the design methods of the Renaissance. The obvious contrast between the introverted habitus of his figures, especially in the psychology of their faces, and the bizarre folds of their wildly moving robes, vividly describes his art-historical specificity. Schönermark (1886) already pointed out the peculiarities of the consoles, which consist of sweeping renaissance structures, decorated with pearl bars, notched ribbon motifs, acanthus leaves and palmettes. But its figures are still fundamentally Gothic, even if the inclusion of the Renaissance currents is clearly visible. “This somewhat tricky standing with twisted legs or a higher foot and the pushing forward of a shoulder that protrudes as wide and clearly as possible from under the robe can be observed in almost all of Halle's figures. Their renaissance-like figures are swarmed by vehement, whizzing wrinkles, which are more important in their expressiveness than the bodies they hide. The greatest importance of these figures, however, resides in their heads. Where do we have an equally large series of such important portrait heads in German sculpture, even in the following centuries? Here one can hardly speak of ideal creations, here the artist must have done his studies on models. "

"Peter Schro's figures are not, like those of Tilmann Riemenschneider, tired late Gothic, but mannered, adorned and caught up in a kind of puzzle with or against the viewer." "The clothing of the figures, which are provided with strong sentiment, shows none organizing structures, but is small-scale and fragmented and provided with isolated folds, some of which are strongly moved. Figures and robes fall apart, at the same time optical bars are placed between the figures and the viewer. In this way, Peter Schro's works show all signs of a protomaniac style. ”With this, Goeltzer (1991) follows Pinder's analysis, which is based on the figure of Jacobus the Elder. J. (N4) pointed out the mannerist nuances in the work of the Halle master at an early stage. In his words, the master of the Halle Cathedral Apostles is “one of the mannerists of the late Gothic Baroque”, for whom ecstasy is the first and last word and who pressed his figures into the intoxication of form. The exaggeration of the form, which is particularly evident in the treatment of the garments, is a prelude to the "expressive" mannerism. For Kahle (1939), too, the mannerist exaggeration of baroque pathos in the treatment of clothes, as well as in the accumulation of ornamental motifs and the theatrical liveliness of the emaciated faces are at the center of the art-historical evaluation.

Von der Osten (1973) emphasizes the characterful faces of the apostles, which one notices studies of nature. The disproportionately high structure of folds almost drowns the body of the figures, and the works of art lack the statuary of still images. “They dance, they break forward and retreat, they swing their shoulders, are passionately moved and yet as if spiritually tied up. It is perhaps the most touching sculpture cycle of the epoch, and it is rich precisely because the sculptures do not seem to be composed to one another. "The tendency to limit and to depict the overly sharp physiognomies, that refined, strange, in a word - that internalization of expression was the artist's deeper concern. This was a specific part of the religious language of that time that was used and lived in the liturgy of the New Abbey. “Under the influence of the Devotio moderna , the longing for internalization developed in the late Middle Ages.” The stone sculptures of the New Abbey express this longing for internalization in a very special way.

Erroneous identification attempts

Bastian Binder

Redlich (1900) determined Master Bastian Binder from 1520 as head of the structural changes to the cathedral in Halle. According to the archive documents it would be possible that u. a. he provided the drafts for the plastic and architectural works of art and perhaps also carried out the fine sculptural work by hand. “The execution was evidently carried out according to the drafts and under the supervision of a master, probably under Bastian Binders himself or under Conrad Fogelsberger.” Fogelsberger was identified in later research as Binder’s construction clerk.

Ludwig Binder

Ruhmer (1958) assesses as follows: "The sculptures of the collegiate church were executed under the direction of Ludwig Binder by a community of sculptors composed of Main Franconian elements (perhaps connected to Riemenschneider via Backoffen) and Lower Bavarian elements from the Leinberger sphere." Von der Osten (1973) also supports this judgment: “Ludwig Binder is presumed to be the real master.” Even Harksen (1958) saw no connection with the Halle Cathedral due to the simplicity of Ludwig Binder's figures and sees him more influenced by the illustrations from the Cranach workshop . However, she classifies him as the creator of Hallesches Domkanzel. Neugebauer (2010) gives Ludwig Binder's year of birth as 1512 based on a find at the Johanneskirche in Bad Salzelmen. In any case, Ludwig Binder's age would be too short to carry out the sculptures designed by Grünewald with his journeymen. "When the collegiate church in Halle was rebuilt in 1520–1525, the stonemason had reached the age of eight to thirteen, which also makes his involvement appear questionable." Even if one neglects his age, the complicated depictions of movements and clothes would be in abundance of all degrees Ludwig Binderschen in Hallesches Dom, rather clumsy sculptures, completely foreign.

Matthias Grünewald

Several authors see Grünewald as the senior master who provided the designs for the pillar figures. In chronological order, Steinhäuser (1937), Ruhmer (1958) and von der Osten (1973) should be mentioned. Kähler (1955/56) rejects the work of Steinhäuser (1937) on the whole because of “strong errors”, whereby he ascribes a certain value to the photos contained therein. Ruhmer (1958) remarks: "The renovation and decoration of the Hallische Stiftskirche (1518–1526) are subject to the supervision of Matthias Grünewald , who is Cardinal Albrecht's chief art commissioner and stays in Halle between 1521 and 1523." Grünewald, who is behind the work in Halle and was the top construction manager. In summary, Lühmann-Schmid (1975) comes to the conclusion that the view expressed by the authors that Grünewald supplied the designs for the pillar figures and instructed the sculptors, could not be correct for stylistic reasons. "Quite apart from the fact that Mathias Grünewald could not be documented as a sculptor and carver."

Peter Flötner

Sponsel (1924) combines the stylistic features (uniform ornamentation) of the "Mainzer Marktbrunnen with the grave monuments of the Backoffenschule in Mainz and at the same time with the architectural and sculptural furnishings of the collegiate church in Halle as well as the early Renaissance works of the Halle Cathedral Treasury". He correctly recognizes one and the same master behind it, whose peculiarities of style are said to have developed under the influence of the Lombard Renaissance. Although these assumptions are very consistent, the final conclusion, the assignment of the designs for these works to Peter Flötner , is not convincing.

Leonhard Pucheler

In 1936, Hünicken tried to ascribe the works of the “master of Halle cathedral sculptures” to the sculptor Leonhard Pucheler, in whom he saw a Backoffen student and who was documented in Halleschen archive sources between 1521 and 1525. This interpretation has not been followed up in the specialist literature.

Overview of the oeuvre

The attributions known so far are essentially based on the classification by Lühmann-Schmid. In recent times, Meys has taken over all of Lühmann-Schmid's attributions with one exception. In addition, in the 9th work complex, three further works are listed in Dehio, Hessen II and three additional works exist in other literature. The dates of the works are not always consistent between Lühmann-Schmid (1975, 1976/77), Meys (2009) and Thiel (2014).

| Work complexes | designation | Dating | material | Location | Lühmann-S. (1975, 1976/77) | Meys (2009) | Thiel (2014) | Dehio (1999, 2008) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Work secured by inscription | Gravestone for Heinrich Meyerspach († 1520) | 1517/18 | Gray sandstone | Frankfurt-Höchst, St. Justinus | 1975, p. 12 | P. 868 | P. 32 | - |

| Grave slab for Kuno von Walbrunn († 1522) | 1522 | Yellow-gray sandstone | Partenheim i. Rh.hess., Ev. Parish church | 1975, p. 13 | P. 868 | P. 32 | - | ||

| 2. | Early works (c. 1516–1518) | Grave monument for Johann IX. von Kronberg († 1506) and wife († 1525) | around 1517/18 | Red sandstone | Kronberg i. Ts., Castle chapel | 1975, p. 14 | P. 868 | - | - |

| Baptismal font | around 1517/18 | Gray sandstone | Eltville, Catholic parish church of St. Peter and Paul | 1975, p. 17 | P. 868 | - | 2008, p. 208 | ||

| 3. | Works from the period 1518–1520 that crossed the boundaries of the late Gothic | Epitaph for Adam von Allendorf († 1518) | around 1518/19 | Gray sandstone | Eberbach, monastery church | 1975, p. 19 | P. 868 | Pp. 35, 334 | - |

| Crucifixion group (except the cross of Christ) | around 1519 | Main sandstone / Andernacher Tuff | Hessenthal, New Pilgrimage Church | 1975, p. 22 | P. 868 | - | - | ||

| Epitaph for Walter von Reiffenberg († 1517) | around 1520 | Gray sandstone | Kronberg i. Ts., Ev. Parish church | 1975, p. 9 | P. 868 | P. 33 | - | ||

| Crucifixion group (not the assistant figures) | 1520 | Andernacher | Mainz, St. Ignaz Kirchhof | 1975, p. 24 | P. 868 | Pp. 60, 330f. | - | ||

| Grave monument for Count Gottfried zu Dietz († 1522) | 1520 | Gray sandstone | Mainz, St. Stephan | 1975, p. 27 | P. 868 | - | - | ||

| Crucifixion or Mount of Olives group | around 1521 | Red sandstone | Eltville, Catholic parish church of St. Peter and Paul | 1975, p. 29 | P. 868 | - | 2008, p. 209 | ||

| 4th | Works from the years 1521–1523 | Grave monument for Ludwig von Ottenstein and his wife († 1520) | around 1521 | Yellow tuff | Oberwesel, Church of Our Lady | 1975, p. 31 | P. 868 | - | - |

| Christ Thomas group | around 1521 | Gray sandstone / Eifeltuff | Mainz, cathedral | 1975, p. 33 | P. 868 | P. 35 | - | ||

| Epitaph for Andreas Hirde († 1518) | around 1518 | Gray-green Main sandstone | Frankfurt, cathedral | 1975, p. 36 | P. 868 | Pp. 35, 169 | - | ||

| Double grave of Wigand von Dienheim († 1521) and Agnes Forstmeister von Gelnhausen († 1518) | around 1520 | Red sandstone | Oppenheim, Katharinenkirche (west choir) | 1975, p. 40 | - | Pp. 38, 333 | - | ||

| Fragments of an Epitaph Altar (Resurrection of Christ) | 1522/26 | Gray sandstone | Mainz, cathedral cloister | 1975, p. 41 | P. 868 | - | - | ||

| Grave monument for Wild and Rhine Count Philipp († 1521) | 1521/22 | Gray sandstone / tuff | St. Johannisberg, Ev. church | 1975, p. 42 | P. 868 | P. 36 | - | ||

| Epitaph for Johann von Hattstein († 1518) | around 1522 | Gray sandstone / Andernacher tuff | Mainz, cathedral cloister south wing | 1975, p. 45 | P. 868 | Pp. 35, 167, 169, 220 | - | ||

| 5. | Sculptures for Cardinal Albrecht's residence in Halle | Magdalenen Chapel, consecration plaque | 1515/1516 | Andernach tuff | Halle, Moritzburg | 1975, p. 49 | P. 868 | Pp. 34, 150, 172 | 1999, p. 275 |

| Large consecration tablet | 1523 | Tufa | Hall, collegiate church (north wall) | 1975, p. 52 | P. 868 | Pp. 34, 172, 353f. | 1999, p. 254 | ||

| Cycle of pillar figures | 1522/25 | Tufa | Hall, collegiate church (octagonal pillars) | 1975, p. 55 | P. 868 | P. 269 | 1999, p. 253 | ||

| 6th | Wooden sculptures | Mary with child | around 1519 | Limewood | Eltville, Catholic parish church of St. Peter and Paul | 1976/77, p. 58 | P. 868 | - | 2008, p. 208 |

| Double Madonna | around 1520 or 1522 | Limewood | Kiedrich, St. Michael Chapel | 1976/77, p. 61 | P. 868 | - | 2008, p. 508 | ||

| Statue of Saint Catherine | around 1522 | Limewood | Münster-Sarmsheim, parish church | 1976/77, p. 64 | P. 868 | - | - | ||

| 7th | The work of the maturity period in the Mainz area | Market fountain | 1526 | Red sandstone / Odenwald | Mainz, market square | 1976/77, p. 65 | P. 868 | P. 38 | - |

| Grave monument for Katharina von Kronberg-Bach († 1525) | around 1528 | Gray sandstone | Oppenheim, Katharinenkirche | 1976/77, p. 68 | P. 868 | P. 36f., 181 | - | ||

| Grave monument for Kaspar von Kronberg († 1525) and his wife († 1563) | around 1528/30 | Hand down engraving | formerly Kronberg im Taunus (lost), St. Johannes | 1976/77, p. 71 | P. 868 | P. 37 | - | ||

| Epitaph for Heinrich von Sparr († 1526) | around 1530 | Yellow sandstone | Darmstadt, Hess. State Museum (former parish of Groß-Steinheim) | 1976/77, p. 73 | P. 868 | - | - | ||

| 8th. | The work of the late creative phase from around 1530–1540 | Grave monument for Conrad Hofmann († 1527) | around 1535 | Red sandstone | Frankfurt-Höchst, Catholic parish church St. Justinus (north aisle) | 1976/77, p. 75 | P. 868 | Pp. 107, 136, 333 | - |

| Epitaph for Georg von Liebenstein († 1533) | around 1535 | Sandstone | Aschaffenburg, collegiate church | 1976/77, p. 78 | P. 868 | Pp. 491f., 494 | - | ||

| Grave monument for Friedrich von Stockheim († 1528) and wife Irmel von Carben († 1529) | re. 1536 | Sandstone / tuff | Geisenheim, parish church | 1976/77, p. 80 | P. 868 | P. 336f. | 2008, p. 342 | ||

| 9. | Works not discussed by Lühmann-Schmid (1975, 1976/77) | Epitaph for Heinrich von Rhein († 1510) | a few years after 1510 | Sandstone | Frankfurt, cathedral, tower hall (south wall) | - | - | - | - |

| Angel relief | re. 1516 | Sandstone | Taunusstein (Bleidenstadt district), Former Benedictine monastery of St. Ferrutius (tower hall) | - | - | - | 2008, p. 98 | ||

| three-figure crucifixion group | 1518-1520 | Limewood | Parish Church of St. Clemens in Trechtingshausen (since 1899 LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn) | - | - | - | - | ||

| four-figure crucifixion group (wider circle of Peter Schro) | around 1520 | Sandstone | Erbach, cemetery | - | - | - | 2008, p. 226 | ||

| only triumphal cross in the triumphal arch (maybe Peter Schro) | not clear | Wood | Kiedrich, Catholic parish church of St. Dionysius and Valentinus | - | - | - | 2008, p. 505 | ||

| Coat of arms of Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg (Peter Schro workshop) | 1527 | Red sandstone | Landesmuseum Mainz, Inv. No. S 3160 | - | - | - | - | ||

Main work in the cathedral in Halle

Mendicant Order and Collegiate Church of St. Paul on the Holy Cross

The Dominican monks came to Halle in 1271 and built a monastery according to the rules of their mendicant order . A cloister was used to connect the monastery to a Dominican church of St. Pauli built by them to the Holy Cross. In 1283 the church was already partially completed. An excellent representation of the construction phases of the former Dominican church can be found in Todenhöfer (2006). The tasks of the Dominican mendicant orders included pastoral care and preaching, and they were given the right to be buried. Hardly any remains of the monastery have survived. A reconstruction drawing of the cloister buildings of the monastery was made by Koch (1923), completed by Nickel (1966) and recently published by Hamann (2014). The church exists to this day and is known as Hallescher Dom . Although the name “Dom” is factually incorrect (Halle was never the seat of a diocese ), it has become naturalized and has been preserved to this day. The simple church building is a three-aisled hall church with narrow side wings and high octagonal pillars. As far as possible, construction was carried out cheaply in order to satisfy the religious ideal of poverty and thrift. The walls are largely made of rubble stones, the yokes are partly unevenly arranged and the structure is characterized by simplicity and rigor.

The New Pen as the spiritual space of the pillar figures

In 1513 Archbishop Ernst von Wettin received papal approval to found a new spiritual association. After Pope Leo X. had confirmed the establishment of the "New Monastery" in April 1519, Cardinal Albrecht decided to set up the new collegiate monastery in the Magdalenen Chapel of Moritzburg. Since there was soon no longer enough space for the magnificent relics in the small chapel, Cardinal Albrecht moved the Dominican monks to the Moritz monastery in order to use their monastery church for his own purposes. The corresponding contract with the monks was only signed on June 28, 1520, although the relics were moved from Moritzburg to the New Abbey in a solemn procession on June 15, 1520. One can conclude from this that the monks only reluctantly and not entirely voluntarily left their ancestral domicile.

Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg had the New Abbey consecrated in 1523 for two titular saints who had a special meaning for him - for the patronage of Saint Mauritius and Maria Magdalena . The former Dominican Church was named the second highest church in the Archdiocese of Magdeburg and was named "Collegiate Church of St. Mauritius and Maria Magdalena for the Lord's Golden Handkerchief". The patron saint of the New Abbey in Halle was his favorite saint, Saint Ursula . In addition, Albrecht chose Saint Erasmus as co-patron, for whom he had a particular preference. Since Erasmus acted as the patron saint of the Brandenburg Hohenzollern family before 1450, political reasons are also assumed for the introduction of the Erasmus cult in Halle. "In the pen, the depictions of the saints, Mauritius and Erasmus, visualized the connection between empire and church, personified by Charles V and Albrecht of Brandenburg." the relics from the Moritzburg, with lavish wealth and artistic inventory. A reconstruction drawing by Hamann (2014) illustrates the arrangement of the precious furnishings inside the cathedral. This was also the time when the collegiate church was decorated with the large cycle of pillars. The three patron saints were given a prominent position in the pillar figure cycle according to their importance for Cardinal Albrecht. The exterior of the church was also conspicuously redesigned by placing a circumferential gable wreath made of semicircular fields on the building. The semicircular gable wreath fields were each crowned with balls in early Renaissance forms.

“Life in the New Abbey was shaped by the daily liturgy . Whether clergy or layperson, the first duty of the more than fifty members of the monastery was to attend the daily church services. ”In the church, spread over the day, there were lively celebrations by citizens of Halle and clergy. “If all the clerics who were obliged to worship were present, then in the understanding of medieval man the whole Christian city was present. This substitute function for the residents of the city of Halle was made tangible in a liturgical element that was familiar to everyone, the ringing of bells ... Anyone who heard the 'little measuring bell' could pause and commemorate the Passion of Christ. ”In this respect, the new pen took care of the imagination of the time for the salvation of all citizens of the city.

The collegiate church only existed for a few years, because as early as 1539 Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg ordered to give up his residence in Halle. Probably its main reason was the ever advancing triumph of the Reformation. The entire inventory, including the library, the valuable reliquary treasures, carpets and furniture were transported to Aschaffenburg and Mainz. He only left the works built into the cathedral in Halle, which means that the pillar figure cycle has been preserved to this day. The collegiate church was handed over to the Dominican monks again on May 9, 1541, who returned to their former monastery church. They stayed there for a relatively short time until 1564 when they gave up their church. Looking at the figures today, the most obvious mutilations can be seen in the figure of Saint Erasmus. His arms are cut off and the facial area is almost completely unrecognizable. Since the face of Erasmus is said to have carried the features of Albrecht, the destruction of the figure is associated with the bitter demeanor of the returning Dominican monks or the counter-reactions of the Reformation.

The church remained unused until it became the Protestant court church of the administrator Johann Friedrich von Brandenburg in 1589. Albrecht's free-standing bell tower next to the collegiate church was torn down at the end of July 1541, and his largest bell was brought to Magdeburg. In 1680, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg named the cathedral the Reformed Court Church. In 1686 Reformed French religious refugees ( Huguenots ) united to form a Reformed congregation, which merged with the German Reformed congregation in 1809. Today it is incorporated into the regional church of the ecclesiastical province of Saxony. An outline of Halle's urban development to this day can be found in Brülls and Dietzsch (2000).

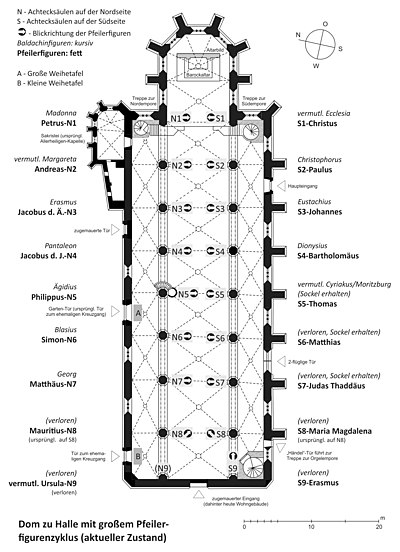

Large pillar figure cycle

- Location: Hall, collegiate church, pillar of the central nave.

- Material: tufa. - Average height of the pillar figures 200 cm, the canopy figures 65 cm, the consoles 55 cm, the canopy housing 220 cm. Total height approx. 500 cm.

- State of preservation: The sequence of figures is incomplete because the pillar figure of St. Ursula no longer exists. In addition, three canopy figures (S5 – S7) and the housing have been lost on the south side (their canopy consoles are present). Since an organ gallery was built in the middle of the 17th century, the canopies of Magdalena and Mauritius disappeared when the organ construction was rebuilt. The Erasmus figure on the west wall of the church is up to knee height in the floor of the upper floor for the organ, the canopy is no longer there. It is very badly damaged.

Arrangement and significance of the figures

The figure cycle consists of 17 sculptures, which were placed about 600 cm above the floor (lower edge of the console). These are Christ , 13 apostles (instead of Judas , his successor Matthias is shown and Paul is also included) and three additional saints ( Mauritius , Maria Magdalena , Erasmus ), who are connected in a special way to the New Abbey. The figures stand on richly decorated consoles. Above them are canopies, which consist of a housing and a canopy figure inside. The canopy housings protectively surround the canopy figures, which are significantly smaller compared to the pillar figures, which are Maria , Ecclesia and 9 of the 14 helpers in need. There are also three bases, the canopy figures of which have been lost.

The statues of Mauritius and Maria Magdalena (S8 / N8) were repositioned and exchanged several times. As they were partially covered by the baroque organ gallery, they were installed at the foot of the two eastern gallery stairs in 1959, with the sides being reversed to ensure that the viewer could be seen. In 1996 they were fastened back to their original pillar location - however, they remained reversed to their original pillar suspension, as otherwise they would only have been visible from the rear. On the console of the Mauritius there is also a male half- portrait with the inscription ANNO DOMN. M. / DXXV . The date when the figures were completed in 1525 can be derived from this. Presumably it is the self-portrait of Peter Schro, who wanted to secure himself at the feet of the main patron of the church (N8-Mauritius), whose protection and intercession. With one exception, the lettering is on the hems of the robes. Just the quote from 1 Cor. 9.22 of the Paul figure (S2) is on the cloak sleeve.

Since Saint Ursula is a patron saint of the New Abbey in Halle, it is assumed that the missing pillar figure in the north pillar N9 can only be her. There are various legends surrounding the Ursula figure. What many have in common is that they are associated with "Ursula Rehdinger", the presumed lover of Cardinal Albrecht. It plays an important role in the pre-academic literature on Albrecht. Since there are three drawings with double portraits of Albrecht and Saint Ursula, an attempt was made to derive Ursula Rehdinger's appearance from them. In addition, Albrecht's intention is rumored to have a portrait of Ursula Rehdinger depicting the figure of Saint Ursula. However, there is no evidence of a historical Ursula Rehdinger.

The internalization of the figures contrasts with the overall attitude of the pictorial works, which is tense to the point of tearing, and thus expresses their transitional character in art history. While the repetitive motifs of the folds of the robes correspond to a Mannerist phase of the late Gothic, the expressive design of the heads and hands of the figures heralds the new structure of the Renaissance. A “study of nature” on the model can also be assumed. Rhenish tuff was used as the material for the figures, a very soft and porous rock that is easy to work with. The larger figures were partially dismantled in Mainz and then transported to Halle and assembled with wires and putty. The smaller consoles and canopy figures may have been made in Halle. “Individual parts of the figures that stand out more strongly from the block, such as hands or folds, were added with a black, pitch-like putty. The finely crafted decorative elements on the canopies were reinforced with inlaid iron wires. However, these iron wires formed the occasion for later destruction; because when the metal began to rust, it split off parts of the surrounding stone. ”The figures were originally painted in color. In the late 19th century they were given a thick coat of lime, which has now been removed. In some places traces of the painting have been preserved and can still be seen today.

Ruhmer (1958) expresses himself impressively on the importance of the pillar figures by calling them “perhaps the most expressive sculptures of the German 16th century”. The statement can be understood from the pictures of the pillar figures, which are juxtaposed in their sequence and commented on in their essential attributes and inscriptions.

Pillar figures

- Pillar figures on the south side

| pillar | Pillar figure | existing attributes | lost attributes | inscription |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Christ | Globe | Cross on globe |

SALVATOR // MVNDI // QVI CREDIT • IN • ME • ECIAM SI • MORTV // VS // FVERIT The savior of the world. Whoever believes in me (he will live) even if he has died. [Joh. 11.25] |

| S2 | Paul | book | sword |

ΠΑΣΙ • ΓΕΓΟΝΑ • TA • ΠΑΝΤ (Α) I have become everything to everyone. [1. Cor. 9, 22, text on the left sleeve of the coat]. SANCT (V) S // PAVLVS • O (RA) Saint Paul pray (for us) |

| S3 | John | Eagle, chalice with snake | - |

S (ANCTVS) • IOHANNES • [A] POSTVLVS • ORA Holy Apostle John, pray (for us). |

| S4 | Bartholomew | Book, knife, skin | - | - |

| S5 | Thomas | Book, stick | lance |

SANCTVS • THOMAS • APOSTOLVS • Holy Apostle Thomas. |

| S6 | Matthias | - | Book, stick |

SANCTV (S) MATHIAS Saint Matthias. |

| S7 | Jude Squidward | Club | rosary |

[S] (ANCTVS) [I] VDAS • THADEVS • ORA (Saint) Judas Thaddäus, pray (for us). |

| S8 | Mary Magdalene | Ointment box | - | - |

| S9 | Erasmus | Book, crosier | Winch (torture tool) | - |

- Pillar figures on the north side

| pillar | Pillar figure | existing attributes | lost attributes | inscription |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Peter | Book, key, forelock | - |

S (ANCTVS) • PETRVS • APOSTVLVS • O (RA) Holy Apostle Peter, pray (for us). |

| N2 | Andreas | Book, fork cross | - | - |

| N3 | Jacobus d. Ä. | padded coat, pilgrim's staff, bag and hat | - |

• S (ANCTVS) • IACOBVS • APOSTVLVS • ORA Holy Apostle Jacobus, pray (for us). |

| N4 | Jacobus d. J. | Book, walker rod | - |

• S (ANCTVS) • IACOBVS • MINOR • // • APOSTVLVS Holy Apostle Jacobus Minor. |

| N5 | Philip | Book, stick | right-angled bar cross |

SANCTVS • PHILIPPVS • APOSTOLV (S) Holy Apostle Philip. |

| N6 | Simon | Saw, loop on the left shoulder | book |

S (ANCTVS) • SIMON • APOSTO (LVS) Holy Apostle Simon. |

| N7 | Matthew | Book, sword | - |

• S (ANCTVS) • MATHEVS • APOSTVLVS • ORA • PRO • NOBI (S) Holy Apostle Matthew, pray for us. |

| N8 | Mauritius | Sword, eagle shield | Flag shaft, lance tip |

ANNO / D (OMI) NI • M • / D • XXV In the year of the Lord 1525. [Text on heraldic shield, console] |

| (N9) | (presumably Ursula) | lost | ||

Canopy figures

In the 17th century a royal box was built on the south side of the cathedral. As a result, the canopies and the figures of the needy helpers of Thomas, Matthias and Judas Thaddäus were removed. Cyriakus was later rediscovered in the Moritzburg depot. Achatius, Vitus and the sculptures by Katharina and Barbara can no longer be found.

- Canopy figures on the south side

| pillar | Pillar figure | existing attributes | lost attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Ecclesia | Chalice | Rod cross |

| S2 | Christophorus | - | Christ child, fruit-bearing tree trunk |

| S3 | Eustachius | deer | left antler, crucifix |

| S4 | Dionysius | severed head with miter | Crosier |

| (S5) | (presumably Cyriacus) | meanwhile lost, kept in the Moritzburg | |

- Canopy figures on the north side

| pillar | Pillar figure | existing attributes | lost attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Madonna | Child, crescent moon | - |

| N2 | Margareta | - | - |

| N3 | Erasmus | - | - |

| N4 | Pantaleon | Hands nailed to the head, short skirt | - |

| N5 | Aegidius | Beret, arrow, dome with hood | - |

| N6 | Blasius | Child at feet | Crosier |

| N7 | George | short skirt, feather hat | lance |

Further exemplary major works

For the temporal classification cf. Table with an overview of the oeuvre.

Consecration plaque in the Magdalenen Chapel

- Location: Halle, Moritzburg, Magdalenen Chapel, north face.

- Material: Andernach tuff, 190 × 105 cm.

- Conservation status: Mauritius, Stephanus and the gore puttos show severe damage to the heads. Hands and fingers partially broken off. Round arch renewed with tracery.

a) Classification

The consecration plaque for the Magdalenen Chapel was donated by Cardinal Albrecht to commemorate and consecrated the chapel personally on the feast day of the titular saint in 1514. The chapel served as the first storage and exhibition space for Cardinal Albrecht's extensive and valuable collection of relics. It “is the earliest surviving example of the use of Renaissance elements in sculpture in Halle and is thus an invaluable piece for the development from Gothic to Renaissance.” The surface-filling function of the individual figures and the sense of elegance and effect become a decorative overall effect subordinate. The melancholy undertone cannot be overlooked in the decorative, playful presentation. Both refer to components of the Schroschen design canon. The oversized coat of arms pushes the figures to the side and contrasts with the three delicate helmets. A peculiarity of the Schro style is visualized in the spread position of the feet of the Mauritius and in the advancement of shoulder and free leg into the room - completely in contradiction to the prevailing law of the surface.

b) Meaning

Mauritius and Saint Martin act as actors, at whose feet lies the beggar who has received half his coat as a gift. Both maintain the coat of arms of Cardinal Albrecht, which is divided into nine areas. St. Stephen is on the lower left of the inscription and Mary Magdalene is depicted on the lower right, next to the plaque. In the middle field of Albrecht's coat of arms there are three smaller heart coats of arms that belong to the cities of Mainz, Halberstadt and Magdeburg. Accordingly, the cities are assigned their respective title saints - Mauritius is the patron saint of Magdeburg, for Mainz it is Saint Martin and for Halberstadt it is Saint Stefan. Maria Magdalena is the church patroness. Since the cardinal had been Archbishop of Magdeburg as Albrecht IV since 1513 and Apostolic Administrator for Halberstadt as Albrecht V., he also became Archbishop of Mainz in 1514. In this respect, the tablet documents the immense power with which he was endowed. The inscription under the coat of arms reads:

OPT (IM) O • MAX (IM) O • AC • DIVE • MAGDALENE • / TVTELARI • ALBERTVS • CVIVS • HEC • / SIGNA • DIGNITATE (M) • GENVSQVE • DE • / CLARA (N) T • HA (N) C • EDEM • IPSE • DEDICAVIT • / AN (NO) • CHRI (STI) M ° • D • XIIII • KAL (ENDAS) • AVG (VSTI) XI ° • (To the best and the highest and the holy (Mary) Magdalena as The patron saint consecrated Albrecht, whose dignity and descent are shown by these coats of arms, even this temple in the year of Christ 1514, eleven days before the calendar of August.)

Large consecration plaque in Hallesches Dom

- Location: hall, collegiate church, north aisle.

- Material: tuff, 208 × 152 cm.

- Conservation condition: Ornaments of the round arch, the lateral tendrils and parts of the cardinal's hat and the cross staff are destroyed or damaged. Arm parts of several figures are broken off. The left putto is completely missing.

a) Classification

When the collegiate church was consecrated in 1523, there were several reasons for Cardinal Albrecht to have a second, significantly larger consecutive tablet made by Loy Hering after the smaller consecration tablet. On the one hand, the first heraldic plaque could not have been representative enough for him and, on the other hand, the inclusion of Saint Ursula in the circle of titular saints speaks for the necessity of making a second plaque. The large heraldic plaque from the cathedral in Halle joins the consecration plaque of the Magdalenen Chapel in Moritzburg in terms of its artistic design, including the fonts, the pleated garment treatment and the ornaments, as well as the technique of freely carving out individual parts such as the cords or the crook on. It continues the Renaissance style of the consecration table from the Magdalenenkapelle with a higher degree of sophistication and is based on the design of the pillar figures, for which it was created at the same time. "Magdalena and Mauritius are similar to the pillar figures ... The dress of the Magdalena resembles that of the pillar figure, as does the shape of the ointment jar."

b) Meaning

Left and right of the Renaissance temple ( aedicula ) are two candelabra pillars in front of them with distinctive ornamental shapes that delimit the group of figures to the side. It is Saint Mauritius on the left and Maria Magdalena on the right, both of whom are holding up the coat of arms of Cardinal Albrecht. Finely worked cords wind freely from behind their heads. The escutcheon largely covers the crook and sword, which are set up crossed and surmounted by a lecture cross with a cardinal's hat. A semicircular apse dome vaults the holy figures. Mauritius and Magdalena guarantee the protection of the large national coat of arms "of the cardinal who sees himself as the new patron of the church". At the base of the consecration plaque is the inscription that pays tribute to the founder of the plaque and expresses the date of the consecration. The bust of St. Erasmus is placed to the left of the inscription, while St. Ursula is positioned on the right. The inscription under the coat of arms reads:

DEO • OPT (IMO) • MAX (IMO) • DIVOQ (VE) • MAVRICIO • AC • MAG = / DALENAE • TVTELARIB (VS) • ALBERTVS • CVIVS • / HAEC • SIGNA • DIGNITATE (M) • GENVSQ (VE) • / DECLARANT • HANC • AEDEM • / IPSE • DEDICAVIT • AN (NO) • CHRIST • / M • D • XXIII • IX • KAL (ENDAS) • SEPTEM (BRIS) (God, the best and the highest and the holy Mauritius and the (Maria) Magdalena, the patron saint, consecrated this church to Albrecht, whose dignity and descent are shown by these coats of arms, in the year of Christ 1523, nine days before the calendar of September.)

Mainz market fountain

- Location: Mainz, market square.

- Material: red sandstone from the Odenwald. Diameter of the trough 250 cm. Pilaster height 182 cm, width 32 cm.

- State of preservation: The fountain has been restored several times. Only the three pillars and architraves are from the original draw well. The original remains of the arabesque decoration of the crown, which was renewed in 1890, are in the Middle Rhine State Museum in Mainz.

a) Classification

“The art-historical significance and the artistic rank of the market fountain in Mainz have been established for a long time: it is considered to be the oldest and probably most beautiful Renaissance fountain in Germany.” Cardinal Albrecht's redesign of the original drawing fountain in 1526 was caused by two historical events. The victorious battle of Emperor Charles V against the French King Franz I near Pavia (1525) and the subsequent suppression of the rebellious peasant armies in Thuringia, Franconia, Swabia and elsewhere were the reason for the renovation and repositioning of the fountain. Both events are referred to in several inscriptions on the following topics:

- Triumph: DIVO KAROLO • V • CÆSARE • SEMP (ER): AVGVS (TO): POST VICTORIAM GALLICAM REGE IPSO AD TICINVM SVPERATO AC CAPTO TRIVMPHANTE: FATALIQ (UE) • RVSTICORVM PERCARD • GERMANIAM CONSPI = RATIONEBER PROSTRATA (INALIS): ET ARCHIEP (ISCOPUS): MOG (UNTINUS) FONTEM HVNC VETVSTATE DILAPSVM • AD CIVIVM SVORVM POSTERITATISQVE VSVM RESTITVI CVRAVIT. ANNOM DXXVI. (On the occasion of the triumph of the divine Emperor Charles V, the always sublime, after the victory over France, after the defeat of the [French] king himself on the Ticino and his capture, as well as after the suppression of the ominous peasant conspiracy in Germany, Albrecht [von Brandenburg] , Cardinal and Archbishop of Mainz had this old fountain restored for the benefit of its citizens and posterity. In 1526)

- Warning: TO REMEMBER THE WINNER, BUT THE DEFEATED AS AN ETERNAL WARNING.

- Vanitas symbolism : O BEDENCK THE END.

- Self-presentation: ACCIPE POSTERITAS HÆC QVÆ MONVMENTA PARAVIT ALBERTVS PRINCEPS CIVIBVS IPSE SVIS QVOS AMAT EX ANIMO • CVSTOS • AMBITOR HONESTI VTQV (A) E • VICES REDDANT SEMPER AMORE CVPIT. (Hear, posterity, what monuments Elector Albrecht himself created for his citizens, whom he loves with all his heart as protector and promoter of the morally good, and that out of love he always wishes that they reward him with like)

The fountain has undergone several restoration work (putti added in 1767, Madonna figure added in 1890, moved back to the Alte Münze in 1975). The history of the restoration is described in detail by Heinz (2005). Although the attribution of the market fountain to Peter Schro has never been seriously questioned, Heinz (2005) considers the question of the executing master to be extremely difficult and by no means resolved.

b) Meaning

On the roof of the fountain three saints stand in niches with shell crowns. They are Saint Martin and Saint Boniface as the patron saint of Mainz and Saint Ulrich as the patron saint of springs and water. They stand above the dolphin-like mythical creatures on the roof of the fountain and far above the ground-based fountain trough as a representation of the status of the estate. They represent a political message intended to be a warning and warning to enemies and rebels for the future. The Virgin Mary is enthroned with the baby Jesus in her arms above the three saints. High above the fountain, she can be understood as a towering figure of a commitment to the Counter Reformation. A small plaque with the inscription "O consider the end" emphasizes the vanitas symbolism in addition to the political issue. References to the Apocrypha (“With everything you do, consider the end” / Sir 7.40) or the book of Ecclesiastes (“It is all very vain ... What gain does a person get from all his toil?” / Pred 1,1) can be assumed. The weapons and equipment trophies in the pillar niches contain an impermanence motif that refers to the historical defeat of the citizens and peasants in 1525. The three columns that stand on the fountain trough contain allegorical motifs from the peasant and bourgeois world (helmets, shields, partisans, swords, forks, flails, pitchforks, hoes, rakes, wooden spoons, salt bowls, bellows and flutes. The reminder of the memento mori refers urgently to the depiction of a drunken farmer, above whom a skull and the said Vanitas inscription are placed. The message is to recognize the elementary violence of the authorities and to make the subjects aware of their own powerlessness.

Epitaph for Andreas Hirde in Frankfurt Cathedral

- Location: Frankfurt, Dom, north transept.

- Material: gray-green Main sandstone, 262 × 161 cm.

- State of preservation: Considerable mutilations and plaster additions, loss of the coronation figure of a risen Christ (Christ Resurrectus) , which Mylius (1866) can still prove .

a) Classification

The epitaph for Andreas Hirde, in contrast to other sculptures from the Middle Rhine region of this time, primarily uses northern Italian ornaments from the early Renaissance in Lombardy . For the first time, the shape of a small temple with candelabra pillars is used ( aedicule shape ). Characteristic of the epitaph is a small art form with tight lines and sharp stone-cut edges, which leads to an area-filling composition. The pilasters and the arch crown are provided for the first time in the sculptures of the Middle Rhine area with an ornamental arabesque filling.

The main characters are characterized by a gentle and sensitive appearance, some of which take on a melancholy expression. Examples are Pilate , the younger of the prophets (standing on the right pillar), the scribe and the woman, leaning on the parapet on the right. In some of the main characters, Peter Schro's characteristic folds can be seen in the crooks of his arms, where they form a stiff fold triangle due to the congestion of the fabric ( Ecce Homo , Pilatus, scribe and male half-figure leaning next to the woman on the parapet).

b) Meaning

The epitaph makes various references and pictorial ideas to the symbolism of death, judgment and ultimately to the resurrection of man. The two prophet figures on the pilasters are clearly related to the scenes with Christ in deepest humiliation (Ecce Homo) and highest triumph (Christ Resurrectus). The prophets Jeremiah and David are considered the epitome of incorruptibility and justice. Thus they face the unjust and brutal accusers of Christ as witnesses of a just judgment of God. Further symbols should lead the viewer to the realization of the meaning of life, which consists in the ascent from death to eternal life.

The fruit-eating dragons in the plinth above the founding family are a symbol of transience and the destruction of life. Ultimately, they symbolize Satan with his destructive influence in the world. Another vanita symbol is the sphere, which is used several times. In the same way, it characterizes Fortuna, but also the vice and instability of the world. In the main relief a mediating area between death and eternal life is shown. Through the sacrifice of Ecce Homo , man's sins are atoned and his resurrection made possible in the first place. Logically, the upper bezel decoration also has a symbolic meaning. The Christ symbol of the vines growing out of the vase (Joh. 15,1) is confronted with the two profile hybrid beings. The latter are strongly reminiscent of the Janus head of ancient symbolism, the god of doors and gateways and the transience of human fates. Christ Resurrectus is enthroned above everything, to whom everything flows and who watches over everything.

Epitaph for Georg von Liebenstein

- Location: Aschaffenburg, collegiate church, third north nave pillar from the east.

- Material: sandstone, 250 × 100 cm.

- Conservation status: good. The crucifix's hand, legs, and nose are damaged. The sword, armor and a corner of the console are also broken off on the knight's statue.

a) Classification

The Liebenstein epitaph shows the insecurities that persist to this day in the attribution of the sculptures from the workshop of Peter Schro. Merkel (2004) refers to the research that, in addition to Moritz Lechler, also includes Loy Hering among the possible sculptors. Lühmann-Schmid (1976/77) accepts the collaboration of a younger student or journeyman because of some quality differences within the work (e.g. plumpness of the large feet, holes in the eyes, etc.). She also thinks of her son, Dietrich Schro, who was still in his father's workshop. Thiel (2014) expresses reservations about this assignment, because it misses the high level of portraiture in the Liebenstein epitaph, which otherwise characterizes Dietrich Schro's work. In principle, however, Dietrich Schro's participation in the work is considered possible. “As far as Peter Schro's part is concerned, the Liebenstein epitaph presents itself as a typical old work, as it is in the economy of means and in the retreat of dynamism and detail. The architectural structure of the epitaph, the figuration of the knight's figure and the exquisite shape of the shell segments show a mature artistic talent and a sovereign freedom of design. In its overall impression, however, the Liebenstein epitaph no longer has the organic cohesion and the harmonious interlocking of all pictorial elements of the earlier works due to the introduction of a second artist's temperament. "

b) Meaning

The tomb was donated by Margrave Johann Albrecht von Brandenburg, the cousin Cardinal Albrechts. It brings the margrave's sense of friendship towards. the dead man who was his chamberlain. Liebenstein came to the Mainzer Hof during his studies and belonged to the more intimate circle of friends of Johann Albrechts. The inscription under the base refers to the “charity” of Johann Albrecht, who owes the erection of the monument for his court chamberlain, who was deported in the prime of his years. The epitaph shows a knight who worships the crucified on the crucifix. The half-length figure of God the Father is shown in the wreath of clouds, with the dove of the Holy Spirit appearing in the crown. In this respect, it is a trinity group, whereby the cross and the feet of the knight overlap the frame and protrude over the edge as a creative trick. "It is not a visionary appearance before the eyes of the praying knight, but an actual devotional image - a picture within a picture."

reception

Although Peter Schro was an unknown artist for many years, his person and his work in Hallesches Dom have been dealt with in the form of a novel and photography.

The Nameless One (Steinhäuser, 1937)

The comparisons of the sculptures in Halle Cathedral with Grünewald's paintings and drawings prompt the author to see the master of Halle cathedral sculptures in Grünewald. The focus of the novel is on the reconstruction and decoration of the cathedral in Halle under supervision and based on designs by Grünewald. The client Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg and Bastian Binder appear as well as Hans Schönitz , the confidante Cardinal Albrecht and the brilliant Dürer . While Grünewald supplies the designs for the pillar figures and decorations, the Hall servants and stone masons from Mainz carry out the work.

The photos (Zwicker, 1947)

In February 1947 the Halle photographer Eberhard Zwicker (* 1915 to † 1999) captured the pillar figures on the pillars of the nave in Halle Cathedral. For this he used a wooden camera from 1898 with a Steinheil brass lens. Under adverse conditions, Zwicker succeeded in capturing the figures and faces of the apostles and saints with high artistic quality. A special exhibition showed his photographs in the Stadtmuseum Halle (Saale) from October 13, 2013 to January 19, 2014. The texts accompanying the pictures are primarily dedicated to iconographic references to the pillar figures as well as related legends and attributes of saints.

After the great uprising (Neutsch, 2003)

Erik Neutsch's historical novel deals with the painter Matthias Grünewald in the years of the Reformation and the peasant wars. At the center of the work is the work on his main work, the "Isenheim Altarpiece". In addition to the portrayal of Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder Ä. is also presented by name in the novel "Peter Schroh" as the sculptor of the pillar figure cycle in Halle. Cardinal Albrecht's work is also discussed. Overall, the novel deals with the behavior of the artist in times of historical upheaval and struggles, with the artist's demands on himself and with his failure in front of a great contemporary backdrop.

literature

- Hans Backoffen . In: General Artist Lexicon . The visual artists of all times and peoples (AKL). Volume 6, Saur, Munich a. a. 1992, ISBN 3-598-22746-9 , pp. 177 f.

- Hans Backoffen . In: Wolf Stadler (Ed.): Lexicon of Art. Painting, architecture, sculpture. tape 1 : Aac-Barm . Karl Müller Verlag, Erlangen 1994, ISBN 3-86070-452-4 , p. 342 .

- Bastian Binder . In: General Artist Lexicon . The visual artists of all times and peoples (AKL). Volume 11, Saur, Munich a. a. 1995, ISBN 3-598-22751-5 , p. 76.

- Ludwig Binder . In: General Artist Lexicon . The visual artists of all times and peoples (AKL). Volume 11, Saur, Munich a. a. 1995, ISBN 3-598-22751-5 , p. 95.

- Franz Bischoff: News about Ulrich Creutz or How long did late Gothic artists' working life last? In: Jiři Fajt, Markus Hörsch (ed.): Artistic interactions in Central Europe (= Studia Jagellonica Lipsiensia . Volume 1 ). Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 3-7995-8401-3 , p. 347-369 .

- Gertrud Braune-Plathner: Hans Backoffen . Academic publishing house, Halle 1934 (56 pages, dissertation, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg).

- Holger Brülls, Thomas Dietzsch: Architectural Guide Halle on the Saale . Dietrich Reimer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-496-01202-1 .

- Harald Busch, Bernd Lohse (Hrsg.): European sculpture of the late Gothic and Renaissance (= monuments of the west ). Umschau Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1963.

- Georg Dehio: The master of the gemming monument in the cathedral of Mainz . In: Yearbook of the Prussian Art Collections . tape 30 , 1909, pp. 131-144 , JSTOR : 25168685 ( deutschestextarchiv.de ).

- Bernhard Eddigehausen: The epitaph for Andreas Hirde in the Frankfurt Cathedral of St. Bartholomew . In: Hessian homeland . tape 61 , 2011, p. 13-17 .

- Martin Filitz: Dom Halle (= Small Art Guide . Volume 1955 ). 2nd, revised edition. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2006, ISBN 3-7954-5675-4 .

- Ernst Gall, Ute Bednarz et al .: Handbook of German Art Monuments . Ed .: Georg Dehio. Saxony-Anhalt II: Dessau and Halle administrative districts . German Kunst-Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-422-03065-4 .

- Ernst Gall, Folkhard Cremer et al .: Handbook of German Art Monuments . Ed .: Georg Dehio. Hessen II: Darmstadt administrative district . German Kunst-Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-422-03117-3 .

- Gustav Glück: The art of the Renaissance in Germany, the Netherlands, France, etc. Propylaen Verlag, Berlin 1928.

- Wolf Goeltzer: The "Hans Backoffen case", part 1 . In: Mainz magazine . tape 84/85 (1989/1990) , pp. 1-78 .