Icelandic political system

The Icelandic political system is a parliamentary republic. The most important piece of legislation is the Icelandic constitution .

The legislature forms the Althing , the executive the president and the government. The head of state is the president, he is directly elected by the people. The Icelandic Prime Minister conducts the actual affairs of government . The judiciary has a two-tier structure. The lower level is formed by the district courts, the upper level by the Hæstiréttur Supreme Court , the supreme court, which also functions as a constitutional court.

Iceland achieved on the Democracy Index of the magazine The Economist in 2019 to second place.

legislative branch

The Althing is the legislative power in Iceland.

Althing

The Icelandic parliament Althing has 63 members who are elected every four years. The Althing can be prematurely dissolved under certain conditions.

Members of the Althing are elected in a proportional representation based on the preference system in six constituencies. Until 1991 the Althing was divided into an upper and a lower house and was then transformed into a unicameral parliament.

Citizens aged 18 and over are entitled to vote.

executive

president

The President is the head of state of Iceland. He represents Iceland under international law. His term of office lasts four years and begins on August 1st of each election year. It is determined by direct popular vote in a simple majority vote. If no alternative nominations have been received by the deadline, the only candidate without a vote ( silent election ) will be determined by the President of the Supreme Court to be legally elected. Citizens from the age of 18 are eligible to vote in presidential elections, the candidate must have reached the age of 40.

The current head of state since August 1, 2016 is President Guðni Th. Jóhannesson .

According to the constitution of 1944 , which essentially replaced the king of the constitutional monarchy with the president of the republic, executive power rests with the president, who leaves it to his government. He appoints these or individual ministers ( ráðherra ) and dismisses them at the meetings of the Reichsrat ( ríkisráðsfundur , president and cabinet). He is not bound by the majority in parliament, i. H. the government ( ríkisstjórnin ) is neither elected nor approved by parliament. In general, however, he follows the politically possible majorities, even when coalitions change during the legislative period. In practice, all presidents stayed out of day-to-day politics into the 21st century and limited themselves to their representative tasks as symbols of the unity of Iceland.

All laws must be presented to the President for signature. If he refuses to sign, the law initially comes into force, but must immediately be submitted to the people for a vote, whereby it is finally accepted or rejected. This can be interpreted as a limited right of veto, but it is only a reference to the people as sovereign. In over 60 years of political practice since the proclamation of the republic, no president had ever made use of this right, so that some Icelandic constitutional lawyers regarded it as forfeited in political tradition. This sparked heated controversy when President Grímsson first refused to sign a controversial press law in 2005. The government at the time repealed the law in question by another act, thus pre-empting a vote.

At a meeting of the Reichsrat on December 31, 2009, then-President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson announced a second time that he would refuse to sign a law (results of the Icesave negotiations). As a result, an executive law had to be passed on the circumstances of the referendum, in which the people rejected the law in March 2010.

Prime Minister and Government

The Prime Minister ( forsætisráðherra ) and the Ministers ( ráðherra ) are appointed by the President of Iceland. This has a free hand and can theoretically appoint a so-called extra-parliamentary government. In practice, after elections, the leader of the largest party in a possible coalition is usually charged with forming a government. The number of ministers is determined by law. The prime minister and the ministers together form the government, but each minister is responsible for managing his department; this can lead to a very free interpretation of the coalition agreements in the administration of office. Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir has been since November 2017 .

Judiciary

The judiciary has a two-tier structure. The lower level is formed by the district courts, which are located in the eight former administrative districts. The Supreme Court ( Hæstiréttur Íslands - Supreme Court) also functions as a constitutional court. In addition, according to the constitution, there is still the possibility of convening a so-called regional court ( Landsdómur ) for the purpose of indicting ministers and presidents . This was first used in autumn 2010. The judges of the regular courts, like all other civil servants, are appointed by the competent minister after an application process.

In May 2016, the Althing passed a law presented by Interior Minister Ólöf Nordal , which aims to introduce a three-tier judiciary. Between the district courts and the Hæstiréttur, there will now be regional courts as the middle level ( Landsréttir , not to be confused with the above-mentioned Landsdómur special court ).

Political parties

The Icelandic party system was described by the French political scientist Jean Blondel in 1968 as a multi-party system with the independence party as the dominant party. In a 2009 survey of Iceland's political system, this statement was said to remain valid. In this context, Grétar Thor Eythórsson and Detlef Jahn write of Iceland's “classic [m] five-party system”. In addition to the four big “old” parties, a changing smaller party was represented in parliament for a long time.

The four most important political parties in Iceland were from 1968 to 1999 (the capital letters indicate the designation of the electoral list, the party letter ):

- The Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur, D, conservative, business-friendly)

- The Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkur, B, rural-liberal)

- The Social Democratic Party of Iceland (Alþýðuflokkurinn, A, social democratic, pro-European)

- The People's Alliance (Alþýðubandalagið, G, socialist)

Furthermore, the following parties have been successfully represented in parliamentary elections at least once since 1946 (see above):

- National Protection Party (Þjóðvarnarflokkur)

- Union of Liberals and Left (Samtök frjálslyndra og vinstri manna)

- People's Awakening (Þjóðvaki, VA, a split from the Social Democratic Party)

- The women's alliance (Samtökin around Kvennalista; SUK)

- The Icelandic Liberals (Frjálslyndi flokkurinn; F, national conservative, represented the small-scale fishermen )

- The Citizens' Party (Borgaraflokkurinn, right-wing populist, existed from 1987 to 1994)

- The citizens 'movement (Borgarahreyfing; H; citizens' protest against the party of four [the established parties])

In the attempt in the late 1990s to unite the People's Party, which is oriented towards social democracy but limited to an intelligentsia, with the People's Alliance and the Women's List, which is oriented towards socialism, in order to build up a powerful New Left, there was again a division into today's social democratic and pro-European

- Alliance or gathering movement (Samfylkingin (abbr.Sf); S)

and the left-green-patriotic

- Left-Green Movement (Vinstri hreyfing-Grænt framboð; (VG for short); V)

who have thus inherited the two former left popular parties.

For the time being, the four or five party system was restored. In the 2010s, however, the Icelandic party landscape has become increasingly fragmented and the number of parties in the Althing has increased. After the parliamentary elections in Iceland in 2017 , eight parties are represented in the Althing, more than ever before.

The new parties include:

- Píratar , the Icelandic Pirate Party ; P (until 2016: Þ). Founded in 2012, in parliament since the 2013 election .

- Viðreisn (“reform”, “rebuilding”), liberal, pro EU accession; C. Founded in 2016, in Parliament since the 2016 election .

- Flokkur fólksins (“People's Party” or “People's Party”), populist; F. Founded in 2016, in Parliament since the 2017 election.

- Miðflokkurinn ("Center Party"), populist, against EU accession; M. Founded for the 2017 election and since then in parliament.

Two of these parties are split offs: Viðreisn was founded by former members of the Independence Party who opposed the party's skeptical stance on the EU, and the Center Party is a re-establishment of Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson , the former Prime Minister of Iceland and leader of the Progress Party. Another party, the eco-liberal and EU-friendly Björt framtíð (“Bright Future” or “Bright Future”), had been represented in the Althing since the 2013 election and in 2017 was part of the short-lived coalition of the Bjarni Benediktsson government , but was able to in the election of October 28, 2017 no longer move into parliament.

Since in practice no party wins a sole majority due to the diversity of parties and the electoral system, coalitions are the order of the day. Preferred constellations have emerged over the decades, but at least the four established parties have come together to form coalitions with all possible combinations of a two-party and even three-party coalition. The Independence Party and the Socialist Party - which later became the People's Alliance - even found each other as government partners from 1944 to 1947, with the Social Democratic Party as a third member.

Unions

There are various branch unions and a trade union confederation ( Alþýðusamband Íslands , ASÍ) in Iceland ; more than 90% of the employees are organized in it. The cooperative system plays an almost uniquely strong role worldwide, albeit with a decreasing trend. Almost all important areas of life (pensions, special holiday payments, health care, child and youth recreational facilities subordinate to school, many cultural events, fishing vessel pools and their distribution of income, etc.) are partially or fully regulated by cooperatives.

Administrative division

Politically Iceland is divided into eight regions: Höfuðborgarsvæðið , Suðurnes , Vesturland , Vestfirðir , Norðurland vestra , Norðurland eystra , Austurland and Suðurland .

The eight regions are (traditionally, but not administratively) divided into 23 sýslur ( Syssel , about counties) and 20 independent municipalities (eight kaupstaðir , seven bæir , one borg and four others).

At the lowest administrative level there are 79 Sveitarfélög (municipalities) (as of 2007), including the eight kaupstaðir (as of 2005).

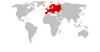

Memberships in international organizations

Iceland is a member of the following organizations: FAO (since 1945), United Nations (since 1946), NATO (since 1949), Council of Europe (since 1949), Nordic Council (since 1952), EFTA (since 1960), OECD (since 1961) , UNESCO (since 1964), OSCE (since 1975/1992), West Nordic Council (since 1985/1997), Barents Sea Council (since 1993), EEA (since 1994), WTO (since 1995), Baltic Sea Council (1995), Arctic Council (since 1996), member of the International Whaling Commission again since October 2002 , in addition to these memberships, the defense agreement with the USA (since 1951) is particularly important for Iceland .

On July 17, 2009 Iceland submitted a now withdrawn application to join the European Union .

literature

- Grétar Thór Eythórsson, Detlef Jahn: The political system of Iceland . In: Wolfgang Ismayr (Ed.): The political systems of Western Europe . 4th, updated and revised edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, pp. 195–218. ISBN 978-3-531-16464-9

- Carsten Wilms: Iceland . In: Jürgen Bellers, Thorsten Benner, Ines M. Gerke (ed.): Handbook of foreign policy . R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich / Vienna 2001, pp. 120-124. ISBN 3-486-24848-0

Individual evidence

- ↑ Democracy-Index 2019 Overview chart with comparative values to previous years , on economist.com

- ↑ Gabriele Schneider: In future three legal instances . In: Iceland Review Online . May 27, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ A b c Grétar Thor Eythórsson, Detlef Jahn: The political system of Iceland . In: The Political Systems of Western Europe . 4th, updated and revised edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16464-9 , pp. 200 .

- ↑ Frauke Rubart: The party system Islands . In: The party systems of Western Europe . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-531-14111-2 , p. 267-269 .

- ↑ Christina Bergqvist et al. (Ed.): Equal democracies? Gender and politics in the nordic countries . Scandinavian University Press, Oslo 1999, ISBN 82-00-12799-0 , pp. 320 ( online at Google Books ).

- ↑ Jelena Ćirić: Forming a Government Will Prove Challenging ( English ) In: Iceland Review . October 30, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.