Political system of Belgium

The Belgian political system describes how in the Kingdom of Belgium state and extra-state institutions make generally binding rules as a result of certain political decision-making processes. The Belgian political system is democratically oriented and organized as a constitutional, parliamentary hereditary monarchy , in which the power of the king as head of state has been limited by the constitution since 1831 .

Originally conceived as a unitary state designed, Belgium applies also in 1993 after several radical reforms officially state in which the responsibilities between the federal government and the constituent state are authorities, the so-called communities and regions spread. These have their own parliaments with legislative powers and their own governments. In the region around the capital Brussels in particular , a complex network of institutions has been set up to protect the Flemings who are a minority there, but who are in the majority compared to the Walloons across Belgium . In the east of the country there is finally the small German-speaking community , which also has its own institutions.

The political party landscape in Belgium is characterized in particular by the absence of larger national parties . As a result of the Flemish-Walloon conflict , the former all-Belgian parties were split into independent northern (Flanders) and southern (Wallonia) branches. Some of the German speakers also have their own parties or branches.

Form of government and system of government

monarchy

The Kingdom of Belgium is a monarchy at the national level . The head of state is the "King of the Belgians". On July 21, 1831, Leopold I from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , the first and so far only Belgian dynasty , was the first king of the Belgians to take the oath on the constitution.

Since its establishment, the Belgian state has been a parliamentary, constitutional, parliamentary hereditary monarchy , in which the rights and privileges of the king are enshrined in the constitution itself. The king himself must take the following constitutional oath in front of parliament when he takes office : "I swear to observe the constitution and the laws of the Belgian people, to maintain the independence of the country and to preserve the integrity of the national territory." The constitution provides that the person of the king is inviolable, but in order to prevent any claim to absolutism , it stipulates that the king has “no power other than that which the constitution and the special laws made on the basis of the constitution itself expressly delegate” and that all powers emanate from the nation itself (and not from the king) and are exercised in the manner determined by the constitution. The personal power of the king is also severely restricted by the principle of countersignature . "An act of the king can only take effect if it is countersigned by a minister (...)". The countersignature transfers all responsibility for a decision by the king to the government and ministers. In concrete terms, this means that all tasks that the constitution or individual laws entrust to the king, such as the management of the armed forces, the management of diplomatic relations or even the appointment of a new government, cannot in truth be carried out by the king alone, but always need the cover of a minister.

While the king was still actively shaping politics during the nineteenth century, in the course of the increasing democratization of society and the states of Europe in the following century there was a shift in actual power in Belgium to the elected representatives of the people. Even if the king is still accorded far-reaching constitutional powers, the federal government alone , legitimized by a parliamentary majority , conducts the actual business of government. “The king rules, but he does not rule” ( French le Roi règne mais ne gouverne pas , Dutch de Koning heerst maar regeert niet ). Thus, Belgium today is to be seen as a parliamentary monarchy in which the king mainly takes on representative tasks.

democracy

The Belgian political system has several features that characterize modern democracies :

- Rule of law : The various public institutions do not have unlimited power, but are bound by legal requirements. In fact, powers emanate exclusively from the nation and may only be exercised in the manner determined by the constitution. Institutions must not violate human rights, even in compliance with properly passed laws .

- Free elections : In 1831, Belgian suffrage was limited to the ruling classes ( census suffrage ), but today every Belgian over the age of 18 is entitled to vote in elections. The choice is free and secret . The right to stand as a candidate has now also been extended to all citizens over the age of 18.

- Separation of powers : In Belgium, the three powers of legislature , executive and judiciary are separated from each other. This separation is not strict, but provides for various ways in which the individual organs can intervene in other branches according to the principle of interlocking powers. For example, the king is not only responsible for executive power, but is also involved in the legislative process.

- Fundamental rights : The constitution itself has provided for a number of fundamental rights since 1831, which have been expanded over time.

In the “Democracy Barometer” compiled by the University of Zurich (UZH) in 2012, Belgium achieved above-average values in most aspects.

Belgian federalism

Language conflict as a background

The following conditions exist:

- At the overall Belgian level, the Flemish population is in the majority (6.4 million inhabitants in Flanders versus 3.5 million in Wallonia; Brussels has approx. 1.1 million inhabitants).

- In the capital, Brussels , French-speaking citizens outnumber Dutch-speakers by far (an estimated 80–90% of Brussels residents are French-speaking, against 5–15% Dutch-speaking).

- Especially along the language border and in the Brussels periphery there are municipalities in which the linguistic minority enjoys language facilities (see below).

- Flanders has an economic advantage over the structurally weak Wallonia and has to accept significant transfer payments when financing social security.

There are also important historical and cultural differences between Flemings and Walloons . The Flemish demand for a strong region accepts a weaker federal structure. For a not inconsiderable part of the Flemish population, this regionalism expresses itself as open separatism . The Flemish Movement, the historical driver of these demands, arose from a will to protect and expand the Dutch language and culture in Belgium and especially in Brussels. That is why Brussels, even if de facto a French-speaking city, is still considered part of Flanders from a Flemish perspective. The special protective measures for the French-speaking minority (especially in the suburbs of Brussels, which are geographically in the Flemish region) meet with political rejection. Flanders tends to vote on the right ( Christian-conservative ) and is faced with a strong, albeit declining, right-wing extremist movement.

The Walloons have also made regionalist demands in the past, but in most of the state reforms the francophone side was more inclined to advocate the preservation of the structures of the national or federal state. The Walloon Region has shaped its autonomy less culturally than economically in order to be able to influence the ailing economy and the high unemployment rate in particular. Even if there is a close “intra-francophone” connection between Wallonia and Brussels, Brussels is seen as a fully fledged region with its own needs. There is a broad consensus in Brussels and in Wallonia that language facilities for the French-speaking minority in Flanders should be permanently maintained. In Wallonia in particular, the majority vote on the left ( socialist or social democratic).

Despite the mutual prejudices (the Flemish is radical right-wing and separatist, the Walloon clientelistic and work-shy), the culture of compromise and negotiation has been cultivated in Belgium for more than a century . Attempts are made to maintain a permanent balance between the two parts of the population at the different levels. This expresses the aim of the Belgian model of federalism: The various aspirations for autonomy and the resulting potential for conflict are to be channeled through increased autonomy of the regional authorities in order to prevent the state from falling apart.

Principles

Since the fourth state reform (1993), Belgium has officially been a federal or federal state . Belgian federalism is particularly characterized by the following features:

- Centrifugal federalism: At the time of its establishment, Belgium was a unitary state with several decentralized organs (the provinces and the municipalities) which, however, had no legislative sovereignty and were subject to the supervision of the national authority. The transformation into a federal state happened and is still happening out of a centrifugal dynamic, according to which, similar to Canadian federalism , the federal authority transfers more and more responsibilities to the member states over time. The federalism systems of the USA , Germany or Switzerland , on the other hand, for historical reasons tend to be in a centripetal movement that tends to strengthen the federal government, and are therefore hardly comparable with the Belgian case.

- Bifurcation without sub-nationalities: Even if there are three communities and regions in Belgium, the political system remains exclusively shaped by the two dominant population groups, the Flemings and the Walloons. This dualism intensifies existing tensions, as there are no other neutral parties or alternative alliances (the German-speaking minority does not play a major role in this regard). In the constitution, however, there is no mention of Flemings, Walloons, Brussels or German speakers, only Belgians. In purely legal terms, there is no such thing as a “ national citizenship ” that is subordinate to or ancillary to that of Belgium. This is due in particular to the fact that in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital both the Flemish and the French Communities are equally responsible (see below) and the Brussels population should not be forced to choose between the northern or the southern part of the country.

- Structural superimposition: Belgian federalism stipulates that at least two different types of local government are responsible for the same area, one community and one region. However, the respective territorial areas of responsibility of the three communities and the three regions are not congruent. In Brussels, this regional delimitation is particularly difficult. Nevertheless, the French and Flemish Communities are also only allowed to act within their borders. Even if it allows "possible extraterritorial consequences" of certain measures, the Constitutional Court forbids in principle that the member states act outside their respective jurisdiction.

- Exclusive competences: The principle of the exclusivity of competences provides that the material authority of an authority excludes any freedom of action of another authority in the matter concerned, so that there is only one responsible level for each matter. However, this principle has various exceptions, such as parallel responsibilities (matters for which several levels are authorized at the same time, see below) or implicit responsibilities (see also “ implied powers ” ). As a result of this, authorities can partially invade the areas of responsibility of the other levels. The Constitutional Court, however, stipulates three conditions for this, namely that the regulation adopted can be considered necessary for the exercise of one's own powers, that this matter is suitable for a differentiated regulation and that the effects of the provisions in question on the other level are only marginal.

- No federal priority of application: The legal norms of the federal authority and the member state authorities have in principle the same legal force (with a little nuance for the Brussels ordinances, see below). In Belgium there is no priority of application according to the German principle “ Federal law breaks state law ”. The absence of federal priority can be traced back to the principle of exclusive competences (see above): Since, as a rule, several legislators may never be responsible for the same matter, there is no need for a conflict of laws rule .

- Asymmetry: A characteristic of Belgian federalism and one of the main causes of its complexity is the extensive asymmetry of its components, both in terms of the organs, the competences and the position of the member states. The communities and regions of Belgium all have different characteristics: in Flanders, community and region were merged, the French community has transferred competences to the Walloon Region, the Walloon Region in turn has delegated powers to the German-speaking Community and there are several in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital Authorities also responsible (see below).

Division into four language areas

The Belgian state is made up of a federal level - the federal state in the narrower sense, also known as the federal authority - two subdivision levels: the communities and the regions . There are also other regional authorities, some of which also have sub-national competences and are not identified as such in the constitution (such as the Community Commission, see below).

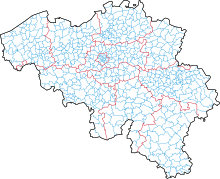

The territorial jurisdiction of the states is determined on the basis of the four so-called language areas of Belgium. These are purely geographical markings without a regional authority or legal personality and were definitely defined in 1962 by the so-called language border . Each municipality in Belgium can only be assigned to one language area.

The four language areas are:

- the Dutch-speaking area

- the French language area

- the German language area

- the bilingual Brussels-Capital area

In 1970, the constitution stipulated that only a special law , i.e. a law with a special majority in the language groups of Parliament, could change the boundaries of the language areas. Thus the course of the language border from 1962 was "concreted" for the future.

Conflict avoidance

In order to avoid legal conflicts of jurisdiction, all draft laws and executive texts with rule content are checked in advance by the State Council with regard to compliance with the rules on the allocation of responsibilities. Complaints about jurisdiction over already adopted legal texts can be brought before the Constitutional Court (see below).

Political conflicts of interest to prohibit, the Constitution provides for the principle of "federal loyalty" ( covenant faithfulness before). Should a parliamentary assembly be of the opinion that such a conflict of interest still exists as a result of a draft text submitted to another assembly, it can apply for the suspension of this draft and consultation by means of a three-quarters majority. If no solution is found, the Senate takes on the matter and submits a report to the so-called conciliation committee. This body is made up of various representatives from the federal, community and regional governments and then looks for a solution by consensus .

Finally, the possibility of more or less close cooperation between the federal state, the communities and the regions is envisaged. So-called cooperation agreements can be concluded in all areas, in some they are even mandatory (such as in the area of international representations, see below). Since 2014, the various communities and regions can also adopt joint decrees and edicts.

Appearance on an international level

Since 1831 the constitution has stipulated that the king (and the federal government) conduct international relations and can sign international treaties . Since the fourth state reform (1993), however, both the governments of the communities and those of the regions within their respective areas of responsibility have been empowered to conduct their own international relations (" in foro interno, in foro externo ") and have the so-called " treaty making power ” . The competence of the federal level was limited accordingly.

In Belgium, therefore, a distinction must be made between three types of international treaty when it comes to the question of jurisdiction:

- Federal treaties: treaties that affect the competences of the federal state (or its “residual competences”) are negotiated and concluded by the king (and the government). The government is in principle completely free and can decide for itself which contracts it wants to sign up to and which not. However, in order for these contracts to be legally binding within Belgium, they require the prior approval of an approval law by the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. An exception to this are negotiations with regard to an assignment of territory, an exchange of territory or an expansion of territory, which may only take place on the basis of a law. This has traditionally been interpreted in such a way that the government requires prior approval from the chambers. In addition, since 1993, Parliament has had to be informed of every opening of negotiations with a view to amending the European Treaties and to be informed of the draft treaty before it is signed.

-

State treaties: within the limits of their competences, the governments of the communities and the regions can conclude treaties in complete autonomy. Since they also legally bind the Belgian state under international law, the constitution reserves the federal government some possibilities of intervention. The member states must inform the federal government in advance if they want to start negotiations with a view to the signing of international treaties. After receiving this information, the federal government has 30 days to notify the government concerned, if any, that it has objections to the treaty; this automatically suspends the aforementioned negotiations and the “inter-ministerial conference on foreign policy” is convened. This is tasked with finding a consensus solution within 30 days. If this is impossible, there is another 30-day period: If the federal government does not react, the suspension of the proceedings is ended and the member state can continue its negotiations. However, if the government wishes to confirm the stay of the proceedings, it can do so solely on the basis of one of the following circumstances:

- the contracting party was not recognized by Belgium ;

- Belgium has no diplomatic relations with this contracting party;

- a decision or action by the contracting party resulted in relations with Belgium being severed, annulled or seriously damaged;

- the draft treaty contradicts Belgium's international or supranational obligations.

- Mixed treaties: In international treaties that affect both the competences of the federal state and those of one or more member states, a cooperation agreement regulates cooperation between the various governments. The federal state must inform the inter-ministerial conference on foreign policy in advance if it intends to negotiate a mixed treaty. The negotiations are conducted by the representatives of the various authorities, with the FPS Foreign Affairs taking over the coordinating lead . In principle, the federal foreign minister and a minister from the member states concerned sign the treaty together. After the signature, the various governments submit the treaty to their respective parliaments for approval and inform each other about this. Only when all parliaments have given their approval does the federal foreign minister prepare the ratification document for Belgium's approval and have it signed by the king.

For the implementation of international treaties, the usual constitutional rules apply with regard to the division of responsibilities between the legislature and the executive on the one hand, and between the federal state and the member states on the other. What is remarkable here is that the federal government can take the place of a member state (and thus “exclude” the federal structure) if it fails to meet its international or supranational obligations. In these cases, the federal state can even claim back the costs incurred. However, intervention by the federal authority is only possible if these three conditions are met:

- the Belgian state has been convicted by an international or supranational court for failure of a member state;

- the authority concerned received three months' notice;

- the federal state involved the authority concerned throughout the procedure.

The representation of Belgium in the various assemblies and bodies at international level also provides for a complicated interaction between the federal government and the various governments of the member states. Cooperation agreements have been concluded for Belgium's representation in international organizations (such as the Council of Europe , the OECD or the United Nations ) or in the EU Council of Ministers . The way in which the federal authority can represent the member states before the international courts of law was also regulated in a cooperation agreement.

Overview of the political system

|

VIOLATED

LEVELS

|

legislative branch | executive | Jurisdiction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European union |

|||||||||

| Federation (Belgium) |

|

||||||||

| LANGUAGE AREA | nl | nl / fr | fr | de | nl | nl / fr | fr | de |

no facilities 5) |

|

Communities |

Flemish Parliament 1) | Flemish government | |||||||

| Council of COCOF 3) | College of COCOF 3) | ||||||||

| Council of COCOM / GGC 4) | College of COCOM / GGC 4) | ||||||||

| Regions |

Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region 3) 4) |

Parliament of the Wallonia Region 2) | Government of the Brussels Capital Region 3) 4) | Government of the Walloon Region | |||||

|

Provinces |

no facilities |

|

no facilities | ||||||

|

Communities |

no facilities |

|

no facilities | ||||||

Federal level

Territory and responsibilities

The federal state exercises its powers over the entire territory of the Belgian state. Its responsibilities can be divided into two categories:

- Assigned competences: These are competences expressly assigned to the federal level by the Constitution or a special law, such as defense or judicial policy. These competences can also be expressed in the form of a reservation: although the legal system provides for the basic competency of the communities or regions, it reserves exceptional cases for which the federal state continues to be responsible. However, some of these are broadly defined, such as social security , the minimum amount of the statutory subsistence level , commercial and company law or currency policy .

- Remaining competences : The federal state retains the remaining competences, such as civil law , for all areas of activity or policy that have not been expressly assigned to the communities or regions . These numerous areas cannot be exhaustively listed.

It is also worth mentioning the parallel competences , which provide, as an exception to the principle of exclusive distribution of competences (see above), that both the federal state and the communities and regions, each individually, have the same authority over a matter. These responsibilities include, in particular, research funding , development cooperation , the special administrative supervision of subordinate authorities (see below), infrastructure policy and the possibility of introducing criminal sanctions or expropriation .

Finally, the constitution itself also refers to the institutions of the federal authority as the constitution- giver (see below). In this way, the federal state exercises the competence-competency in which both its own competences and the competences of the other regional authorities can be determined and changed.

legislative branch

- The Federal Parliament of Belgium

Legislative power is exercised by the Federal Parliament together with the King. The Parliament consists of the Chamber of Deputies (or simply "Chamber") and the Senate . The Belgian bicameral system is, however, unevenly aligned, since the chamber has more numerous and more important competences vis-à-vis the Senate, especially since the fourth state reform (1993). These institutions are based in Brussels . The active and passive right to vote for women at the national level did not exist until 1948 on the same conditions as the right to vote for men.

Chamber of Deputies

The Chamber of Deputies ( Dutch Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers , French Chambre des Représentants ) is the lower house of Parliament and has 150 members. It is divided into a Dutch language group (currently 87 MPs) and a French language group (currently 63 MPs). In contrast to the Senate, the number of members of each language group in the Chamber is not fixed. Depending on how the population develops and the relationship between Flemish and French-speaking citizens changes, the language groups in the Chamber have more or fewer seats after each election.

The people's representatives are directly elected by the population for five years; the elections will take place on the same day as the European elections and the Chamber will be fully renewed on that date. The election is based on the system of proportional representation . All Belgian citizens who have reached the age of eighteen and are not in one of the statutory exclusions are entitled to vote ( active right to vote ). To become a member of the Chamber ( right to stand for election ), four conditions must be met: the candidate must be a Belgian citizen, have civil and political rights, be at least 18 years old and be resident in Belgium. Nobody may be a member of the chambers and the Senate at the same time.

The Chamber of Deputies performs the following tasks in particular:

- Federal legislation: The Chamber of Deputies exercises federal legislative power together with the Senate and the King (see below).

- Government control: In a democracy, a government can only exist if it can rely on a parliamentary majority. This is done by reading out the government declaration and the subsequent vote of confidence , which the federal government has had to ask the Chamber of Deputies - and no longer the Senate - before it takes office since the fourth state reform (1993). The government must also answer and answer questions from parliament for its policies. The government ministers are solely responsible to the Chamber of Deputies. The control of the government also includes the control of the individual ministers and state secretaries, whose presence the Chamber of Deputies can request. The members of parliament have a “right of interpellation ” and, following each interpellation, can seek a vote of confidence in the minister or the government.

- Budget: Government control extends in particular to the state budget and finances . Only the Chamber of Deputies is authorized to approve the budget annually. The Chamber is supported in budgetary control by the Court of Auditors .

- Investigation right: The Chamber of Deputies has an investigation right, which means that it can set up an investigative committee that has the same powers as an investigating judge .

- Constitutional revision: The Chamber of Deputies acts together with the Senate and the King as constitution- giver (see below).

- Succession to the throne: The Chamber of Deputies and the Senate play a decisive role in determining a successor to the king (see below).

The Chamber of Deputies is automatically dissolved if a declaration of constitutional revision is submitted (see above). For his part, with the countersignature of a minister and the majority agreement of the Chamber, the King has the right to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies in the following cases and to call new elections within 40 days:

- if a vote of confidence by the government is rejected and the Chamber does not propose a successor to the Prime Minister for appointment within the next three days;

- if a motion of censure against the government is accepted and a successor to the Prime Minister has not been proposed at the same time ( constructive vote of no confidence );

- if the federal government resigns.

The current President of the Chamber of Deputies is Siegfried Bracke ( N-VA ).

senate

The Senate ( Dutch Senaat , French Sénat ) is the upper house of parliament. Since the founding of the state in 1831, it has undergone far-reaching reforms in terms of its composition and responsibilities: from an assembly reserved for the aristocracy , it has developed into a "deliberation chamber ". However, there are regular calls for the introduction of a unicameral system and the final abolition of the Senate.

The Senate has 60 members who can be divided into two categories:

-

Community and regional senators : 50 senators are appointed from among their number by the parliaments of the communities and regions according to the rules set out in the constitution.

- 29 senators from the Flemish Parliament or from the Dutch language group of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (VGC). At least one of these senators must be resident in the bilingual Brussels-Capital area on the day of his election;

- 10 Senators from the Parliament of the French Community. Of these senators, at least 3 must be members of the French language group of the Brussels-Capital Parliament (COCOF), one of these 3 not necessarily being a member of the French Community Parliament;

- 8 senators from the Parliament of the Walloon Region;

- 2 senators from the French language group of the Brussels Capital Region Parliament (COCOF);

- 1 Senator from the Parliament of the German-speaking Community;

-

Co-opted Senators: 10 Senators are appointed by the aforementioned Senators.

- 6 senators from the senators of the Dutch language group;

- 4 senators from the senators of the French language group.

According to this, 35 Dutch-speaking, 24 French-speaking and 1 German-speaking senator are represented in the Senate. The latter does not belong to any official language group. The conditions for being elected as a Senator (passive right to vote) are the same as for the Chamber of Deputies (see above). The directly elected senators as well as the senators "by law" (that is, the children of the king) were abolished on the occasion of the sixth state reform (2014).

Since the sixth state reform came into force (2014), the Senate has only limited powers:

- Federal legislation: Even if the constitution continues to provide that it exercises federal legislative power together with the Chamber of Deputies and the King, the Senate is only legislative in the limited cases of bicameral proceedings provided for in the constitution (see below).

- Government control: The government is solely responsible to the Chamber of Deputies (see above). Nevertheless, the Senate can request the presence of the ministers for the purpose of hearing if the Senate is discussing a law in a two-chamber procedure. In all other cases he can only “ask” the ministers to be present.

- Budget: The only authority of the Senate to manage the budget concerns the approval of its own budget. The Chamber of Deputies is solely responsible for all other aspects of the state budget (see above).

- Constitutional revision and succession to the throne: Here the Senate continues to play its role as a full second chamber (see below).

- Information report : Since the sixth state reform (2014), the Senate, unlike the Chamber of Deputies, no longer has the right to investigate (see above). Instead, the Constitution now provides that he can deal with “issues that also have consequences for the powers of the communities or regions” in an information report.

- Conflicts of interest: The Senate has a special role to play in resolving conflicts of interest between the various parliaments (see above).

The mandate of the community and regional senators ends after the full renewal of the parliament that appointed them, while that of the co-opted senators ends after the full renewal of the Chamber of Deputies. Since 2014, the dissolution of the Chamber has not resulted in the dissolution of the Senate.

The current President of the Senate is Christine Defraigne ( MR ).

Legislative process

The federal legislative norms are called laws. The deputies, the senators (but only within the framework of the mandatory two-chamber procedure) and the government have the right of initiative and can submit legislative proposals or drafts. These are usually passed with an absolute majority (50% + 1, i.e. at least 76 members of the Chamber and possibly 31 senators) of the votes cast with a majority of the members present (50% + 1). In the case of special laws , the majority ratios are different.

The constitution provides for three different legislative procedures:

- One-chamber procedure: This has been the standard procedure since the sixth state reform (2014), while the two-chamber procedure is the exception. For example, initiatives in civil law, criminal law, social law or court organization are dealt with using the unicameral procedure. The possibility of a second reading is provided for in this procedure.

- Obligatory two-chamber procedure: In 1831, this procedure of absolute equality between the chamber and the senate was still the norm. Today it is only used in cases in which the structure of the state (constitution and special laws), control of political parties or the organization and financing of the Senate is affected. In these cases, a bill or proposal must be passed by both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate in the same wording before it can be submitted to the King for execution.

- Non-binding two-chamber procedure: In this procedure, the Chamber of Deputies decides, while the Senate takes on the role of an “advisory and deliberation chamber ”. The Senate can review draft bills or proposals from the Chamber within set deadlines and propose amendments (right of evocation). The final decision, however, always rests with the Chamber of Deputies. This procedure applies to laws implementing special laws, laws ensuring compliance with international and supranational obligations, laws governing the Council of State and federal administrative jurisdictions, and some special laws mentioned in the Constitution.

The laws are only legally binding once they have been published in the Belgian State Gazette .

The constitutional revision procedure differs from the normal legislative procedure: First, those articles are identified that are to be released for revision. The corresponding lists are published in the State Gazette. After this declaration the parliament dissolved by operation of law. It is therefore common for such declarations on constitutional revision to take place at the end of a regular legislative period. After the new elections, the Chamber and Senate, together with the King, are to be considered constitutional. This means that you can (but don't necessarily have to) change the articles that were on the lists - and only these articles. The amendment of a constitutional article requires a special quorum and a special majority (two-thirds majority with two-thirds of the members present).

executive

- The federal executive power of Belgium

The federal executive power rests with the King , currently King Philippe . The personal power of the king is, however, severely restricted by the principle of countersignature, whereby the entire responsibility for a decision by the king is transferred to the federal government and the ministers (see above). In concrete terms, this means that all tasks that the constitution or individual laws entrust to the king (such as the management of the armed forces, the management of diplomatic relations or even the appointment of a new government) cannot in truth be carried out by the king alone, but always require the approval of a minister. So it is actually the government and the individual ministers who make all the political decisions of the executive and merely submit them to the king for signature. This signature of the king, although today it is no more than a simple formality, remains necessary; In principle, the government cannot “rule alone” either.

king

Belgium has been a monarchy since the state was founded in 1831 and the head of state is the "King of the Belgians" ( Dutch Koning der Belgen , French Roi des Belges ), whose personal powers are regulated by the constitution, as is usual in a constitutional monarchy (see above). In addition to his function as head of state for all of Belgium, the king is also part of the legislative and executive power at the federal level. The constitution also stipulates that the king may only become head of another state at the same time with the consent of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.

The constitution stipulates the principle of the hereditary monarchy , in which the succession is regulated “in a straight line over to the natural and legitimate descendants of SM Leopold, Georg, Christian, Friedrich von Sachsen-Coburg, according to the law of the firstborn ”. Illegitimate children of the king are therefore excluded from the line of succession . The passage originally recorded in 1831 on the “permanent exclusion of women and their descendants” from the crown ( Lex Salica ) was deleted from the constitution in the mid-1990s. The constitution also provides that a successor forfeits his right to the throne if he marries without the king's approval . However, with the consent of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, the king can reinstate the rights of the person concerned. If the king has no descendants, the king can designate a successor with the approval of parliament; if no successor has been appointed at the time of his death, the throne becomes vacant . If this occurs, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate first determine a regent and, after new elections, finally ensure that the throne is replaced.

When the king dies, the Chamber of Deputies meets with the Senate; these then form the "united chambers". The heir to the throne then swears the constitutional oath before the united chambers; only in this way does he take the throne. The saying “ The king is dead, long live the king ” does not apply in Belgium. The constitution does not formally provide for the king's abdication , but in this case the same procedure is followed as in the event of the king's death. If the heir to the throne is still a minor or if the reigning king is unable to rule (for example due to serious illness), the united chambers ensure guardianship and regency. The reign may only be transferred to a single person and the regent must also take the constitutional oath.

To cover the costs of the monarchy, the civil list is established by law at the beginning of each king's rule .

Federal government

The federal government or federal government ( Dutch Federale regering , French Gouvernement fédéral ), sometimes simply called "Belgian government" or "national government" (outdated), exercises executive power at the federal level. It is made up as follows:

- Prime Minister: The Prime Minister is the federal head of government and thus one of the most important political officials in the country. He must be able to distinguish himself as the “Prime Minister of all Belgians” and strive for a linguistically neutral position. Since the Belgian state is based on a large number of sensitive compromises between the two large communities, the Constitution therefore provides for a special statute for the Prime Minister. When it comes to the question of the linguistic affiliation of the Prime Minister, it deviates from the principle of a balance between Dutch- and French-speaking ministers in the Council of Ministers (see below) by “possibly excluding” the Prime Minister. With this formulation, the Prime Minister can present himself as neutral on the one hand (he does not have to “decide” on a language) and on the other hand does not have to deny his origin. The Prime Minister heads the government as primus inter pares and chairs the Council of Ministers. He represents the government in the various institutions and represents the country on an international level.

-

Ministers: The number of ministers in the federal government has been fixed at a maximum of 15 since 1993, including prime ministers. With one exception for the prime minister, the constitution stipulates a linguistic balance in government: "With the possible exception of the prime minister, the Council of Ministers has as many Dutch-speaking as French-speaking ministers". It is also stipulated that the federal government must be composed of both male and female ministers. In order to be appointed as minister, the following conditions must be met:

- Have Belgian nationality;

- Not be a member of the royal family;

- Not in one of the incompatibility cases. In order to comply with the separation of powers, a member of the Chamber or Senate ceases to meet as soon as he accepts a ministerial office.

- State Secretaries: The State Secretaries are an integral part of the government, but do not belong to the Council of Ministers in the narrower sense and are always subordinate to a minister. The competence of a state secretary never excludes that of the higher minister, and this minister always remains authorized to take on certain files himself. There is no maximum number and no necessary balance between Dutch and French-speaking state secretaries. Otherwise the statute is identical to that of the ministers and they basically have the same powers as the ministers.

The king appoints (with the countersignature of a minister) the government and its ministers and state secretaries. The actual process of forming a government, however, provides for various stages, some of which are based on constitutional rules and partly on political traditions and customs. Thus the king after his first probes, one or more "informators" or "examiner" can ( Informateur ) engage before the actual Regierungsbildner ( Formateur ) determined working out with the coalition parties the common government program and the ministerial distributed in the government. Once the negotiations for the formation of a government have been concluded, the government-builder and the future ministers go to the king's residence and take their oath there. A royal decree by which the king appoints the new government is drawn up and published in the State Gazette . With this step, the old government is officially replaced by the new government. The new government, although legally established, can only function once it has received the trust of the Chamber of Deputies (see above).

The king, that is in reality the federal government, performs the following tasks in particular:

- Executive power: The government, as the executive authority, receives its duties from the legislature. The first execution act incumbent on the government is the sanction and the execution of the laws by the king. The constitution also provides that the king (and the government) adopt the measures necessary for the implementation of the laws without being able to suspend the laws themselves or exempt them from their implementation.

- Legislative initiative: In addition to the members of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, the government also has a right of initiative for the creation of laws (see above).

- Administration and diplomatic corps: the king appoints the officials of general administration and foreign relations. The government organizes its ministries, which since 2000 have been called Federal Public Services (FPS).

- International Relations: The King directs international relations. Since the fourth reform of the state (1993), however, both the governments of the communities and those of the regions within their respective areas of responsibility have been authorized to conduct their own international relations (see above).

- Armed forces: The king formally commands the armed forces , establishes the state of war and the end of the fighting. He will inform Parliament as soon as the interest and security of the state permit and add the appropriate notifications. It goes without saying that the king, although he is the constitutional commander in chief , no longer exercises this responsibility himself, but leaves it to the defense minister. This is advised by the military commander (CHOD - Chief of Defense) . The king also awards ranks in the army and military medals by countersigning the defense minister.

- Judicial system: the decisions and judgments of the Belgian courts and tribunals are carried out on behalf of the king. The King appoints the judges of the courts and tribunals, appoints their presidents and also appoints the members of the prosecution in accordance with the modalities of the Judicial Code. While the government can also dismiss members of the public prosecutor's office, the judges are generally appointed for life, which gives them a certain degree of independence from the executive. Since 1998, a High Council of Justice has proposed the people who are eligible for judicial office.

- Others: The king has the right to mint . The king is also given the privilege of conferring titles of nobility . But the constitution specifies that such titles should never be linked to a privilege.

Just like the appointment, the dismissal of the government or individual ministers is formally incumbent on the king (with the countersignature of a minister). The end of a government can be brought about in three cases:

- Resignation: If, in this case, no new majority can be found in parliament, the king can, after the Chamber of Deputies has approved with an absolute majority, order the dissolution of the chambers and call early new elections.

- No confidence vote: the government loses the majority in the Chamber of Deputies. This approves a motion of no confidence with an absolute majority and proposes a new prime minister to the king for appointment. If no new prime minister is proposed at the same time as the vote of no confidence, the king can dissolve the chambers and order new elections.

- Declined vote of confidence: The government also loses the majority in the Chamber of Deputies in this case. The absolute majority of MPs refused to trust the government after it had asked the Chamber of confidence. Within three days of this rejection, the Chamber of Deputies proposes a new Prime Minister to the King for appointment. If no new prime minister is proposed within three days of a vote of confidence rejected, the king can dissolve the chambers and order new elections.

Judiciary

Judicial power comprises three jurisdictions that are structured differently: ordinary jurisdiction, administrative jurisdiction and constitutional jurisdiction .

The ordinary jurisdiction deals with all private and criminal law matters as well as legal disputes in commercial , labor and social law . The judicial organization applies to the whole of Belgium and has a pyramidal structure, with the higher authority generally being the level of appeal:

- There are various peace and police courts at the base.

- At the level of the 12 judicial districts there are the courts of first instance, which include the various civil, criminal, juvenile, family or investigative courts, as well as the specialized commercial and labor courts ( lay courts ). Each judicial district has at least one public prosecutor's office headed by the king's procurator. There is also an Assisenhof ( jury court ) in each province and in Brussels , which deals with particularly serious crimes.

- On the penultimate level are the five appeal and work centers, which are located in Brussels, Antwerp , Ghent , Liège and Mons .

- The Court of Cassation has been at the head of the ordinary jurisdiction since 1831 . The Court of Cassation decides in the last instance on appeals against decisions of the subordinate courts, whereby it can either collect or confirm them, but not decide itself. He also decides in cases of doubt about the jurisdiction of the legal process to the ordinary or administrative courts.

The Council of State has been at the head of administrative jurisdiction since 1946 . It presides over a large number of subordinate federal and community or regional administrative jurisdictions, each of which covers a specific area (such as the Council for Disputes against Foreigners).

The constitutional jurisdiction is since 1980 by the Constitutional Court (formerly Court of Arbitration perceived), composed of twelve judges, who monitor compliance with the Constitution by the legislature in Belgium. He can declare laws, decrees and ordinances null and void, declare them unconstitutional and temporarily revoke them for violations of Title II of the Constitution (Rights and Freedoms of Belgians), Articles 143 (“Federal Loyalty”) and 170 and 172 (Legality and equality in tax matters) and 191 (protection of foreigners) as well as against the rules of the division of competences contained in the constitution and in the laws for reforming the institutions. The Constitutional Court judges on the basis of complaints or questions for a preliminary ruling .

State level

Communities

- The three communities of Belgium

Territory and responsibilities

Belgium has been divided into three communities since 1970:

- the Flemish Community , which includes the Dutch-speaking area and the bilingual Brussels-Capital area

- the French Community , which includes the French-speaking area and the bilingual Brussels-Capital area

- the German-speaking Community (often abbreviated to “DG” in German-speaking Belgium), which exclusively includes the German-speaking area

The three communities were created in 1970 on the occasion of the first state reform under the name “Kulturgemeinschaften” (the term “language communities” was never used). The three cultural communities had a council made up of the Dutch and French-speaking members of the Chamber and Senate, with the exception of the German cultural community (now the German- speaking community), whose members were directly elected in the German-speaking area. At the beginning the councils did not have their own executive. It was not until the second state reform (1980) that the communities were given their current names (although the French community has called itself the Wallonia-Brussels Federation since 2011 ) and their own governments. It was not until 1984 that the German-speaking Community was given the power to pass legal texts with the force of law. What is special about the Flemish and French Communities is that in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital they are both responsible for the “bodies which, because of their activities, are to be regarded as belonging exclusively to one or the other community”.

The material areas of responsibility of the communities are specified in the constitution and partly specified by special law:

- Cultural matters: Cultural matters include: protection and illustration of language ; Promoting the training of researchers ; fine arts ; Cultural heritage ; Museums and other scientific and cultural institutions; Libraries , discos and similar services; Media policy ; Support of the written press ; Youth policy ; constant training and cultural animation; Physical education, sport, and outdoor living; Recreational activities ; Education policy (pre-school education in custody schools, post-school and secondary school education, arts education, intellectual, moral and social education); Promoting social advancement ; vocational retraining and further training ; Dual training systems . "In order to prevent any discrimination on ideological and philosophical grounds," the constitution provides for the adoption of the so-called "cultural pact legislation", which thus defines a framework for the communities' cultural scope for action.

- Education: The federal state is, however, reserved the competence in the following areas: determining the start and end of compulsory education ; the minimum conditions for issuing diplomas ; the pension regulations. Furthermore, the constitution provides a special framework for the communities to prevent possible discrimination (in particular the principles of freedom of instruction, the neutrality of state education, choice between religious instruction and non-denominational ethics , right to education, compulsory education).

- Personal matters: Personal matters include: large parts of health policy (including, in particular, hospital infrastructure funding , mental health care, care in old people's homes , rehabilitation services, health care professions licensing, health education and preventive medicine); large parts of personal assistance (including in particular family policy , social assistance policy , admission and integration policy towards immigrants , disability policy , senior citizens policy , youth protection and initial legal advice); the houses of justice and the organization of electronic surveillance ; the family benefits ; the film control with regard to the access of minors to cinemas. In health and social policy, various fields of action are reserved for the federal authority, as it is responsible for social security in general (see above).

- Use of language: The Flemish and French Communities are responsible for the use of languages in (internal) administrative matters, in teaching and in social relations between employer and employee. The German-speaking community, on the other hand, is only authorized to use languages in education. The federal state remains responsible for the general rules of language use in the administrative sector, including the bilingual Brussels-Capital Region, and in the judiciary. See also: Language legislation in Belgium

- International competence: In all areas of responsibility, the communities can enter into internal Belgian cooperations as well as conclude international agreements on an international level in accordance with the principle " in foro interno, in foro externo " (see above).

- Other competences: The competences of the French and Flemish Communities include the power to promote Brussels at national and international level. You can also finance tourist infrastructures in Brussels. The German-speaking Community does not have these responsibilities. The communities are also responsible for research, development cooperation and their own infrastructure policy in parallel with the federal state and the regions (see above).

In addition, the communities have what is known as “constitutive autonomy”, that is to say, the possibility of defining certain modalities for the election, composition and functioning of their respective parliaments and governments themselves, without the intervention of the federal legislature. You can therefore exercise constitutional powers to a limited extent . While the Flemish and French Communities have had constitutive autonomy since 1993, the German-speaking Community was only granted this competence in 2014.

legislative branch

The legislative power is exercised by the community parliaments (former community councils).

- The Flemish Parliament ( Dutch Vlaams Parlement ) has 124 members and exercises its power in the Flemish Community (including Brussels). 118 MPs are directly elected in Flanders and 6 other Dutch-speaking MPs in Brussels. As the possibility of merging community and regional institutions has been taken in Flanders, the Flemish Parliament is also the Parliament of the Flemish Region (see below). The President of the Flemish Parliament is Liesbeth Homans ( N-VA ) and its seat is in Brussels .

- The Parliament of the French Community or the Parliament of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation ( French Parlement de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles ) exercises its power in the French Community (including Brussels). It has 94 members, including 75 Walloon regional members and 19 French-speaking members from the Brussels regional parliament. There are therefore no direct elections to the composition of this Parliament. The President of the Parliament of the French Community is Rudy Demotte ( PS ) and its seat is in Brussels.

- The Parliament of the German-speaking Community (Parliament of the DG) exercises its power in the German-speaking Community and meets with 25 members who are directly elected for 5 years. In addition, certain mandataries from other elected assemblies (such as the members of the Chamber of Deputies elected in the Verviers constituency and the members of the Walloon Parliament who are domiciled in the German-speaking area and who have taken the constitutional oath exclusively or primarily in German) are legally deemed to be advisory members of parliament, i.e. without a decisive vote. President of the Parliament of the German-speaking Community is Alexander Miesen ( PFF ) and the seat is in Eupen .

The community parliaments perform the following tasks in particular:

- Community legislation : The legal texts passed by the parliaments have the force of law in their respective areas of competence and are called "decrees".

- Government control: Government control is also one of the tasks of the parliaments. The ministers of the Community governments are responsible before Parliament; Parliament can therefore require individual members of the government to be present. The initially expressed confidence can be withdrawn by Parliament at any time, either through a constructive vote of no confidence in which Parliament proposes a successor government or a successor minister, or through a rejected vote of confidence.

- Budget: Parliament alone is empowered to approve the budget of the income and expenditure of the Community on an annual basis and to control budget implementation by the government.

- Right of investigation: The community parliaments have the right to investigate. This means that they can set up an investigative committee that has the same powers as an investigating judge.

executive

The executive power of the communities is in the hands of the community governments.

- The Flemish Government ( Vlaamse Regering in Dutch ) exercises both community and regional competencies in Flanders (see above). It cannot exceed ten ministers, one of which must be resident in the bilingual Brussels-Capital area. This is then only allowed to make decisions on community issues. The Flemish Prime Minister is Jan Jambon (N-VA).

- The government of the French Community or the government of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation ( French Gouvernement de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles ) originally provided a maximum of four ministers, one of which must be resident in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital. As part of its constitutive autonomy, the Parliament of the French Community has increased the number of ministers to a maximum of eight. The Prime Minister of the Government of the French Community is Pierre-Yves Jeholet (PS).

- The government of the German-speaking Community (government of the DG) may have a maximum of five ministers, but currently has four government members. Prime Minister of the Government of the German-speaking Community is Oliver Paasch ( ProDG ).

The members of each community government are elected by their parliament. The government candidates who have been nominated on a list signed by an absolute majority of members of parliament are elected as ministers; this list must contain several people of different sexes and determines the ranking of future ministers. If the President of Parliament is not given a list signed by an absolute majority of parliamentarians on the day of the election, separate secret elections are held for members of the government. Finally, the ministers take the constitutional oath before the President of Parliament. Unlike ordinary ministers, the prime minister takes his oath not only in front of parliament, but also in front of the king.

The governments of the communities implement the decrees of the community parliaments, draw up draft decrees and edicts, propose the budget to parliament and draft and coordinate community policies in general. They represent the community in and out of court and organize their respective administration.

Regions

- The three regions of Belgium

Territory and responsibilities

Belgium has been divided into three regions since 1970:

- the Flemish Region , which includes the Dutch-speaking area

- the Walloon region , which includes the French and German language areas

- the Brussels-Capital Region , which includes the bilingual Brussels-Capital area

The regions were constitutionally created in 1970, but in Flanders and Wallonia they were only implemented ten years later during the second state reform (1980) after the relevant special law was passed. The definitive creation of the regions was preceded by a provisional regionalization law. Since there was initially disagreement about the proposed special statute for the Brussels region, it was only created in 1989. It was named “Brussels-Capital Region” (to indicate its specificity) and was framed by a number of specific rules that do not apply to the other regions (see below).

The material areas of responsibility of the regions are determined by a special law:

- Spatial planning: This includes in particular spatial planning and urban development , urban renewal , land policy in general as well as monument and landscape protection .

- Environment and water: This includes in particular environmental protection , waste policy (except for radioactive waste), water supply and compensation in the event of natural disasters .

- Nature protection: This includes in particular nature protection , rural renewal, green areas (e.g. Natura 2000 areas), forest and forest policy, hunting and fish farming .

- Housing: This includes in particular public housing and rental legislation .

- Agriculture: This includes in particular agricultural policy and sea fishing as well as land and cattle leasing. The federal authority remains responsible for the safety of the food chain.

- Economy: This includes in particular economic policy , foreign trade (including the export of weapons ), settlement conditions and tourism . The federal state, on the other hand, remains responsible for public procurement , consumer protection , monetary policy and company law .

- Energy: This includes in particular the supply of electricity and the local transport of electricity (with the exception of nuclear energy ), the supply of natural gas and renewable energies .

- Local authorities: This includes in particular the legislation on the provinces, municipalities and inter-communal institutions, the financing of these authorities as well as the church factories, graves and burials .

- Employment: These include, in particular, job placement , the social economy , the employment of foreign workers, temporary work placement and the various forms of subsidy for employment.

- Public works and transport: This includes in particular the construction and maintenance of the road network and waterways , inland ports and regional airports as well as local public transport .

- Animal welfare

- Traffic safety: This includes in particular the speed limits on public roads (with the exception of the motorways ), the regulation of traffic signs , the technical inspection of vehicles (TÜV) and awareness-raising for road safety measures .

- International competence: In all areas of responsibility, the regions can enter into internal Belgian cooperations as well as conclude international agreements on an international level in accordance with the principle of “in foro interno, in foro externo” (see above).

- Other responsibilities: The regions set the conditions for expropriations. Furthermore, in parallel with the federal state and the communities, the regions are responsible for research, development cooperation and their own infrastructure policy (see above).

In addition, the regions and the communities enjoy what is known as “constitutive autonomy”, that is, the possibility of exercising constitutional powers to a limited extent (see above). While the Flemish and Walloon Regions have had constitutive autonomy since 1993, the Brussels-Capital Region was only granted this competence, subject to special conditions, in 2014.

Finally, it should be mentioned that the Brussels-Capital Region has some specific powers in the cultural field. In addition, just like the Flemish and French Communities, it can advertise Brussels as an international location.

legislative branch

Legislative power is exercised by the regional parliaments (formerly regional councils).

- The Flemish (Community) Parliament also functions as the regional parliament (see above). When it comes to regional affairs, the 118 Flemish regional representatives sit there alone.

- The Walloon Parliament or Parliament of Wallonia ( French Parlement de Wallonie ) exercises its power only in the Walloon Region. It has 75 MPs who are directly elected by the Walloon population for a period of 5 years. The Walloon MEPs who have taken their oath exclusively or first in German (i.e. Walloon MEPs from the German-speaking Community) do not have the right to vote in matters that the Walloon Region has received from the French Community. The seat of the Walloon Parliament is in Namur and the President is Jean-Claude Marcourt (PS).

- The parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region ( Dutch: Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Parlement , French: Parlement de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale ) has sole responsibility for the Brussels-Capital Region. It has 89 members who are directly elected by the population for 5 years. There are two language groups within Parliament, namely the French language group (with 72 seats) and the Dutch language group (with 17 seats). The President of the Brussels Capital Region Parliament is Rachid Madrane (PS).

The regional parliaments perform the same tasks mutatis mutandis in their region as the community parliaments (see above).

As for the legislative norms adopted, the Brussels-Capital Region differs from the other two regions: the Brussels Parliament adopts “ordinances”, while in Flanders and Wallonia the parliaments issue “decrees”. The ordinances have a hybrid legal effect: On the one hand, they can “repeal, amend, complete or replace” the existing laws, which gives them, like the decrees, a clear legal force. On the other hand, only they are given a quality that is more applicable to ordinances without legal force: the ordinances can be checked by the ordinary courts for their conformity with the constitution; if necessary, the courts may refuse to apply unconstitutional order. Furthermore, the legal effect of the ordinances is weakened by a kind of “administrative supervision” which the federal state can exercise over the Brussels-Capital Region as soon as “the international role of Brussels and its function as capital ” are affected. If necessary, the federal government can suspend the decisions made by the region in matters of urban development, spatial planning, public works and transport and the Chamber of Deputies can declare them null and void. The federal government can also propose to a “cooperation committee” what measures it believes the region should take to promote the international statute and function as a capital city.

executive

The regional governments have the executive power of the regions.

- The Flemish Government is the same for the Flemish Region as for the Flemish Community (see above).

- The Walloon government ( French Walloon governorate ) originally provided a maximum of seven ministers. As part of its constitutive autonomy, the Walloon Parliament has increased the number of ministers to a maximum of nine. The Prime Minister of the Government of the Walloon Region is Elio Di Rupo (PS).

- The government of the Brussels-Capital Region ( Dutch Brussels Hoofdstedelijke Regering , French Gouvernement de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale ) provides a “linguistically neutral” Prime Minister (in fact a Francophone) and four ministers (two French-speaking and two Dutch-speaking). In addition, unlike in the other regional governments, there are three regional state secretaries, including at least one Dutch-speaking. The Prime Minister of the Brussels-Capital Region is Rudi Vervoort (PS).

The regional governments perform the same tasks mutatis mutandis as the community governments in their region (see above). A special procedure has only been set up for cases in which there should be disagreement over the election of the Brussels government.

particularities

Transfer of responsibilities

In addition to the basic division of competences, the Belgian Constitution provides for various possibilities according to which the local authorities can “exchange” powers, which considerably increases the asymmetry of the political system (see above).

- Merger: The parliaments of the French and Flemish Communities and their governments can exercise the powers of the Walloon Region and the Flemish Region respectively. This possibility of merging community and region has only been used in Flanders to date.

- Regionalization: This option was introduced in the early 1990s when the French Community was in financial straits. The Parliament of the French Community, on the one hand, and the Walloon Parliament and the French language group of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region ("COCOF", see below), on the other hand, can decide that the Walloon Region in the French-speaking area and the COCOF in the bilingual area of Brussels- Capital to exercise all or part of the powers of the French Community. The French Community must approve the transfer by means of a special decree (two-thirds majority), while the equivalent decrees of the Walloon Region and the COCOF can be adopted by a simple majority. The following responsibilities were transferred in 1993: sports infrastructures , tourism , social support, retraining , further training , school transport , care policy, family policy , social assistance , integration of immigrants and parts of disability and senior citizens policy . This list was expanded in 2014 to include the new health and personal responsibilities that the French Community received as a result of the sixth state reform (2014), with the exception of family allowances, which were only transferred to the Walloon Region, as these allowances are exclusively in Brussels administered by the Joint Community Commission (see below).

-

Communityization: The parliaments of the German-speaking Community and the Walloon Region can decide that the German-speaking Community in the German-speaking area exercises the powers of the Walloon Region in whole or in part. For this purpose, two identical decrees must be passed by a simple majority in the two parliaments concerned. So far, the following responsibilities have been transferred:

- Monument and landscape protection (1994)

- Employment and excavations (2000)

- general administrative supervision of the subordinate authorities (2005)

- Tourism and other responsibilities in the area of subordinate authorities and employment (2014-2015)

Brussels Community Commissions

- The three Brussels Community Commissions

In Brussels, both the Flemish and the French Communities have equal jurisdiction. However, due to the bilingual statute of the area, these powers are usually not exercised directly by the communities themselves, but passed on to so-called community commissions. Since there are no subnationalities in Belgium (see above), these community commissions are not responsible for “Flemish” or “French-speaking” citizens of Brussels, but only for the institutions that can be assigned to the respective community (such as a French-speaking school or a Flemish one Theater group). In addition, following the “de-provincialization” of Brussels, the Community Commissions took over the community competencies previously exercised by the Province of Brabant .

There are three different community commissions, the powers of which differ considerably from one another:

- The French Community Commission ( French Commission communautaire française , COCOF for short) represents the French Community in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital.

- The Flemish Community Commission ( Dutch Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie , VGC for short) represents the Flemish Community in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital.

- The Joint Community Commission ( French Commission communautaire commune , shortly COCOM, or Dutch Gemeenschappelijke Gemeenschapscommissie shortly GGC) exercise common Community powers in the bilingual region of Brussels-off, that is, those responsibilities that are of "common interest" and not solely a community affect.

COCOF

The COCOF, like the VGC, was originally just a purely subordinate authority that was under the administrative supervision of the French Community. It continues to implement the decrees of the French Community in Brussels and can, under the supervision of the French Community, exercise certain community competences independently by issuing “ordinances” and “decrees”. In this respect, the COCOF performs the same tasks as the provinces in the rest of the French Community. In addition to these original tasks of the community commissions, the COCOF also has its own decreed and therefore legislative power in the areas assigned to it (see above). The COCOF is thus a hybrid institution and its council is to be seen as a full parliament for these matters.

The COCOF has a council (own name Parlement francophone bruxellois ), which is composed of the members of the French language group of the Brussels Parliament (72 members), and a college (own name Gouvernement francophone bruxellois ), in which the French-speaking members of the Brussels government are represented (currently three ministers, including the prime minister, and two state secretaries).

VGC

The VGC has far less autonomy than its French-speaking counterpart. Indeed, it is seen by the Flemish side less as an independent institution than as a subordinate authority whose task it is only to apply the Flemish decrees in Brussels. She is entrusted with performing certain tasks in cultural, educational and personal matters under the supervision of the Flemish Community. In this context, the VGC can draft “ordinances” and “decrees”. In contrast to the COCOF, the VGC has not received its own decreed authority, so that the two community commissions perform their tasks in an asymmetrical manner.

The VGC has a council made up of members of the Dutch-speaking group of the Brussels Parliament (17 members) and a college in which the Dutch-speaking members of the Brussels government are represented (currently 2 ministers and a state secretary).

COCOM / GGC

The COCOM / GGC is a hybrid institution: On the one hand, it is a subordinate authority that takes care of the community competences of "common interest" ( matières bicommunautaires , bicommunautaire bevoegdheden ). Just like the COCOF and VGC, the COCOM / GGC can selectively lead its own policy in its areas of responsibility and adopt “ordinances”, which however have no legal value. Their situation in this respect is comparable to that of the provinces in the rest of the country. Although the COCOM / GGC acts as a subordinate authority, there is no other institution in the state structure that would exercise administrative oversight over it - not even the federal government.

On the other hand, the COCOM / GGC is responsible for those personal matters which, according to the Constitution, neither the French nor the Flemish Communities have authority over Brussels; this is a part of personal matters ( matières bipersonnalisables , bipersoonsgebonden aangelegenheden ). This affects the public institutions that cannot be assigned exclusively to a community, such as the public social welfare centers (ÖSHZ), public hospitals or direct personal assistance. Since the sixth state reform (2014), it has also been solely responsible for paying family allowances in Brussels. In these areas, the COCOM / GGC is completely autonomous and - just like the Brussels-Capital Region (see above) - “Ordonnances”, which have legal value, are passed.

The COCOM / GGC has a legislative body, the United Assembly ( Assemblée réunie , Verenigde vergadering ), which is composed of French and Dutch-speaking members of the Brussels Parliament (89 members), and an executive body, the United College ( Collège réuni , Verenigd College ), where the French and Dutch-speaking ministers of the Brussels government are represented (5 ministers, including the Prime Minister). However, the Prime Minister only has an advisory voice and the Brussels State Secretaries do not belong to the college. The College also includes a representative from Brussels from the Flemish Government and from the Government of the French Community in an advisory capacity. The organs of the COCOM / GGC thus roughly correspond to those of the region (see above). Finally, a special task is entrusted to the United Quorum: it also functions “as a consultative and coordinating body between the two communities”.

Lower level

Provinces

The provinces are subordinate authorities that are at a level between the regional and local levels. Because of the dubious added value of this intermediate position, the tasks and the very existence of the provinces are regularly called into question. While there were nine provinces when the state was founded, Belgium has been divided into ten provinces since the division of the former province of Brabant in 1995. At the same time, the bilingual Brussels-Capital area was declared provincial.

There are five Flemish provinces (with administrative headquarters in brackets):

-

Antwerp Province ( Antwerp )

Antwerp Province ( Antwerp ) -

Flemish Brabant Province ( Leuven )

Flemish Brabant Province ( Leuven ) -

Limburg Province ( Hasselt )

Limburg Province ( Hasselt ) -

East Flanders Province ( Ghent )