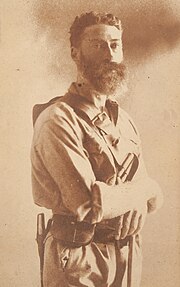

Richard John Cuninghame

Richard John Cuninghame MC FZS FRMetS (born July 4, 1871 in Stewarton , Ayrshire , Scotland ; died May 23, 1925 in Stranraer , Kirkcudbrightshire , Scotland) was a Scottish explorer , big game hunter , natural history museum collector and photographer. He was the leader of numerous safaris , including the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition from 1909 to 1910.

Childhood and adolescence

Richard John Cuninghame was born the son of officer John William Herbert Cuninghame, who served as captain of the 2nd Life Guards. Richard first grew up in Lainshaw House with Stewarton and later attended Bradfield College in Berkshire , according to other sources he attended Eton College . Cuninghame entered Magdalene College at the University of Cambridge on July 28, 1890 and studied biology and medicine, initially with the aim of becoming a doctor. However, he did not graduate.

Explorer and big game hunter

After Cuninghame had dropped out of his studies, he went on a journey. In Lapland he was a hunter and a naturalist, and later he worked on a whaler in the Arctic Ocean . He then went to South Africa and initially worked for the Zeederberg Coach Company as a mail rider on the route from Kimberley to Johannesburg . In 1898 Cuninghame hunted big game. He roamed through Portuguese East Africa , today's Mozambique , South Africa, Matabeleland (today Zimbabwe ), and the Kalahari . In the areas he traveled to, he procured specimens for the British Museum (Natural History) in London.

In 1899 Cuninghame came to Mombasa. Within a few years he gained a good reputation as a big game hunter, taxidermist and photographer. He worked with the safari outfitter Newland, Tarlton & Co. founded in 1904 by Victor Newland and Leslie Tarlton , the market leader in British East Africa. In 1909, Cuninghame was considered the best elephant hunter in all of Africa among trophy hunters . As a professional hunter and tour operator, he led safaris for wealthy European hunting tourists and not only advertised with them, but also with his work as a photographer and collector and taxidermist for European and American museums. He emphasized that he collects all kinds of mammals, birds and fish. If requested, he will take measurements and examine every part of an animal that has been shot or captured using scientific standards, including possible parasite infestation.

With McDouall in East Africa

From 1901 to 1902 Cuninghame and his friend Douglas McDouall carried out an expedition from Mombasa through British East Africa to Lake Victoria , on through Uganda to the Nile and along the river to Cairo . The aim of the carefully prepared expedition was, in addition to the big game hunt, to obtain zoological collection specimens and geographical , geological , climatic and meteorological studies on the way from the equator to Cairo. The expedition was also Cuninghame's first safari .

On December 11, 1901, Cuninghame and McDouall went ashore from a German steamer in Mombasa. They used every opportunity to move faster. So they took the Uganda Railway from Mombasa to Kisumu on the north-east bank of Lake Victoria, saving several weeks. They used canoes on Lake Victoria to cut off a long stretch of their way. Then we went with numerous porters through the steppe of Uganda to the Nile. The expedition was marked by great privations, of which Cuninghame later wrote that they had "marched hundreds of miles through contaminated, arid land without game". Halfway through the distance, when finally game-rich area was reached, Cuninghame fell ill and temporarily went blind in one and then in both eyes.

At this point, Cuninghame and McDouall had to make a decision about whether to continue the trip or return. Finally they made their way back to the Nile. They drove upstream on a paddle steamer, taking numerous measurements of the water depth to map the river. Cuninghame regained his eyesight on the boat trip and was even able to take part in an elephant hunt. Finally they drove downstream on the Nile towards Cairo. The last part of the way they took a train through the desert. Despite his illness, Cuninghame was able to use the experience gained during the trip on later expeditions. In addition, he was able to acquire a good knowledge of Swahili , which he also later benefited from.

Carl Akeley British East Africa Expedition

Around 1905, Cuninghame was working a farm of about 12 square kilometers on the border with Rhodesia. The Carl Akeley British East Africa Expedition of the couple Carl and Delia Akeley took place from 1905 to 1906 , during which specimens for the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago were to be obtained in British East Africa . An important goal was elephant hunting in the area of the Mount Kenya massif . RJ Cuninghame was recommended to the Akeleys as the best elephant hunter in Nairobi, and in 1906 they started working together. Cuninghame had initially refused payment for supporting a scientific expedition, but later gave in. He accompanied the Akeleys to the Aberdare Range , where Akeley could shoot his first elephant. The bull with only one tusk was later exhibited in a group with other elephants at the Field Museum.

Roosevelt-Smithsonian African Expedition

Cuninghame's most significant expedition was the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition from April 1909 to March 1910, during which he served as a guide. Theodore Roosevelt was the leader of the expedition and a hunter with decades of experience. At first he emphatically refused to hire a white hunter for the expedition. Part of this was due to concerns that a white leader might question his authority as the leader of the expedition. He had also heard reports that on safaris the game was sometimes shot by the white guide and not by the guests. Roosevelt said he was only half satisfied if the game he shot contained bullets other than his own. He would not go into this venture as a fraud. It was only after long pressure from Frederick Selous that he gave in and handed the organization over to the leading safari outfitter in Africa, Newland, Tarlton & Co. in Nairobi. The leader of the expedition became Cuninghame, who was recommended to Roosevelt as the best elephant hunter in Africa. Cuninghame was able to convince Roosevelt to hire a second white hunter as his "adjutant", since no one could lead a year-long expedition with 250 men alone. In East Africa, the expedition was therefore accompanied by Tarlton. Kermit Roosevelt later stated that Cuninghame's achievements as a marksman were on par with his father's. But both were surpassed by Tarlton.

The route ran from Mombasa in British East Africa to the Belgian Congo , then to the Nile and along the river to Khartoum . More than 11,000 animals were shot or captured during the trip, Theodore Roosevelt and his son Kermit shot 512 large game alone. The organization on site, namely the selection of the almost 200 porters as well as the askari and the staff for weapons, horses and tents was the responsibility of Cuninghame. On at least one occasion, a hippopotamus attack , Cuninghame is believed to have saved Roosevelt's life. The two men became good friends during the expedition. In his travelogue African Game Trails , Roosevelt later described Cuninghame as slim, wiry, bearded, exactly the type of hunter and safari manager one would want for an expedition like ours . Cuninghame also proved to be a naturalist and excellent collector. The large yield meant that he had to repeatedly support Edmund Heller , who was responsible for taxidermy . Also among the local participants of the expedition Cuninghame was highly regarded and has been called the bearded gentleman ( Bearded Master called), while the Bright Skin Master was. For J. Alden Loring, whose preoccupation with small mammals was interpreted as a sign of cowardice, the porters had nothing but contempt and ridicule, they called him the Mouse Master .

The Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition sparked a safari boom and great demand for guides. Even before Roosevelt's expedition was over, the British royal court engaged Cuninghame as a guide for a Prince of Wales safari . The plans were canceled when Edward VII died on May 6, 1910 and George V was proclaimed the new king.

Smaller safaris and other activities

Cuninghame organized a variety of safaris during his years in British East Africa:

- November 1907 to April 1908 Percy Madeira's safari.

- 1910 the Swedish East Africa expedition. On the journey across the Red Sea to Mombasa, he first met the American writer Stewart Edward White , a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, and his wife Betty.

- July 1910 to 1911 Safari of the writers Stewart Edward and Betty White, with only forty men. In White's travelogue The Rediscovered Land , he mentions Cuninghame with unusual frequency. The report offers a good insight into the course of the safari and the extensive duties of a guide. In 1913 the couple returned to East Africa and were again run by Cuninghame.

- 1911 to 1912 first of two safaris for shipyard owner Robert Lyons Scott. Scott owned significant collections of zoological specimens, weapons, and armor.

- January to March 1914 Safari of Prince Wilhelm of Sweden . Wilhelm toured southern Africa from November 1913 to April 1914 and the safari was the highlight of the trip.

Cuninghame was considered the best guide for safaris in eastern and southern Africa in its day. In addition to his skills as a big game hunter, it was also emphasized that he had unsurpassed knowledge in preparing hunting trophies during an expedition. This was necessary because there were no cooling options and few methods of preservation existed. Cuninghame also benefited from his many years of experience in collecting and preserving animals for zoological collections such as that of the British Museum (Natural History) .

Cuninghame was a founding member and vice president of the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society. Honorary members of this scientific society were some participants of the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition, Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt , Edgar Alexander Mearns , Edmund Heller , J. Alden Loring and the photographer and cameraman Cherry Kearton .

military service

At the beginning of the First World War , Cuninghame was on the second safari with Robert Lyons Scott. At first it was falsely reported that the two had been captured. Cuninghame returned to England to sign up. Because of his age and malaria , he was turned away and went to France, where he joined the American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps . This initially civil organization was associated with the British Red Cross and the St. John Ambulance of the Order of St. John . The corps had the task of transporting wounded soldiers of the Western powers from the French battlefields to the hospitals. When it started operating in the fall of 1914, the Ambulance Corps only had two vehicles and four drivers.

After a while, Cuninghame was recruited by the British Army and used as a scout as part of the British East Africa campaign against German East Africa . His knowledge of Swahili was of great value. In 1916, after a mission to Zanzibar and Mafia , Cuninghame had to go to a sanatorium for some time . After his release, he joined the staff of the Commander of the British Forces in East Africa as a liaison and intelligence officer. During this time he was promoted to major and awarded the Military Cross , after the war the British War Medal and the Victory Medal followed as other war awards . In 1917, Cuninghame was retired because of its malaria and left Africa forever.

Last years

After his discharge from the British Army, Cuninghame moved to the family estate of Hensol House near Castle Douglas in the administrative county of Kirkcudbrightshire . He had inherited the property in 1916 from his uncle Richard Dunning Barré Cuninghame. He married Helen McDouall, the sister of his friend and expedition companion Douglas McDouall. In the years that followed, Cuninghame suffered from malaria and a brain tumor . He died in Stranraer , Kirkcudbrightshire in May 1925 and was buried in the churchyard of the Old Parish Church of Kirkmaiden .

estate

The estate of Richard John Cuninghames remained in Hensol House, initially in the possession of his widow Helen. She married Charles Kennedy in 1933 and last lived again widowed and childless in Hensol House. Helen Kennedy died on February 17, 1959 and bequeathed the property with the Cuninghames estate to her goddaughter Catherine Henderson, the wife of British Admiral Nigel Henderson. The Henderson couple lived in Hensol House from 1971. After the death of Catherine Henderson in 2010, her husband had died in 1993, Hensol House was sold. The inventory, including the estate of Cuninghame, was divided into 583 lots and auctioned on October 24, 2012 at the Bonhams auction house in Edinburgh . The Cuninghame estate included his library with books on natural history and big game hunting, numerous handwritten travel journals, correspondence, notes, photos and equipment such as safari knives and a latrine tent for wealthy customers.

Awards

On December 17, 1889, Cuninghame was awarded the medal and certificate of the Royal Humane Society for rescuing a skater who broke into the ice .

The Royal Meteorological Society elected him on January 15, 1896 as a Fellow .

In recognition of his work as a collector for zoological science, several newly described animal species were named after Cuninghame. These were synonyms for the species already described:

- Crocidura cuninghamei Thomas , 1904, a synonym of Crocidura fuscomurina ( Heuglin , 1865);

- Dentex cuninghamii Regan , 1905, a synonym of Pagellus bellottii Steindachner , 1882;

- Equus quagga cuninghamei Heller , 1914, a synonym of Equus quagga boehmi ( Matschie , 1892), a subspecies of the plains zebra ;

- Mus cuninghamei Wroughton , 1908, a synonym of Mastomys natalensis ( Smith , 1834);

- Mylomys cuninghamei Thomas, 1906, a synonym of Mylomys dybowskii ( Pousargues , 1893).

Publications

- RJ Cuninghame: Concerning the preservation of sea fish by a formalin and soda solution, commonly referred to as 'Jores' solution . In: Journal of The East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society . tape 3 , no. 5 , November 1912, p. 39-43 ( digitized version ).

- RJ Cuninghame: Notes on Collecting Sea Fish at Mombasa . In: Journal of The East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society . tape 3 , no. 5 , July 1912, p. 4–13 ( digitized version ).

- RJ Cuninghame: On the Presentation of a Live Lung-Fish to the Zoological Gardens, London . In: Journal of The East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society . tape 4 , no. 7 December 1913, p. 82-84 ( digitized version ).

- RJ Cuninghame: The Scientific Classification of Some of the Sea Fishes at Mombasa . In: Journal of The East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society . tape 4 , no. 7 December 1913, p. 47-52 ( digitized version ).

- RJ Cuninghame: The Water-Elephant . In: Journal of The East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society . tape 2 , no. 4 , July 1912, p. 97-99 ( digitized version ).

- RJ Cuninghame: The Story of the Elephant . In: Denis D. Lyell (Ed.): African Adventure. Letters from Famous Big-Game Hunters . John Murray, London 1935, p. 226–246 (abridged version of a paper given in New Galloway , March 4, 1921).

- RJ Cuninghame: Notes for a Lecture in New Galloway . In: Denis D. Lyell (Ed.): African Adventure. Letters from Famous Big-Game Hunters . John Murray, London 1935, p. 247–263 (possibly draft of The Story of the Elephant in New Galloway, March 4, 1921).

literature

- Monty Brown: RJ. Robert John Cuninghame. 1871-1925. Naturalist, hunter, gentleman . Self-published, London 2004.

- Theodore Roosevelt : African Game Trails . An account of the African Wanderings of an American Hunter-Naturalist . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1910 ( digitized version ).

- Stewart Edward White : The Rediscovered Land . Doubleday, Page & Company, Garden City, NY 1915 ( digitized ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c J. A. Venn (Ed.): Alumni Cantabrigienses. A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900 . Part 2, vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, London 1944 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c d e f Robert M. Maxon, Thomas P. Ofcansky: Historical Dictionary of Kenya . Second edition (= African Historical Dictionaries . No. 77 ). Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD and London 2000, ISBN 0-8108-3616-5 , pp. 50-52 .

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt: African Game Trails , pp. 3-4.

- ↑ a b Somerset Playne: East Africa (British). Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources . Second impression. tape 1908-1909 . Foreign and Colonial Compiling and Publishing Company, o. O. [Nairobi] 1909, pp. 365-367 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Lot 281. The archive of Richard John Cuninghame. In: Hensol, The Property of a Gentleman. Oct 24, 2012. Bonhams , October 2012, accessed January 16, 2021 .

- ↑ Lot 282. The Akeley's collection of tusks. In: Hensol, The Property of a Gentleman. Oct 24, 2012. Bonhams , October 2012, accessed January 16, 2021 .

- ^ Carl Akeley : In Brightest Africa . Garden City Publishing, Garden City, NY 1923, pp. 153-155 ( digitized version ).

- ^ A b Patricia O'Toole: Roosevelt in Africa . In: Serge Ricard (Ed.): A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt . Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, MA and Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-1-4443-3140-0 , pp. 435-451 , doi : 10.1002 / 9781444344233.ch24 .

- ^ J. Lee Thompson: Theodore Roosevelt Abroad. Nature, Empire, and the Journey of an American President . Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-10277-4 , pp. 18-19 .

- ↑ Patricia O'Toole: When Trumpets Call. Theodore Roosevelt After the White House . Simon & Schuster, New York et al. 2005, ISBN 978-0-684-86477-8 , pp. 45 .

- ↑ Kermit Roosevelt : The Happy Hunting Grounds . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1920, p. 8–9 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt: African Game Trails , p. 150.

- ↑ a b c d Stephanie Clark: The great game hunter who saved Roosevelt's life. In: The Telegraph . October 21, 2012, archived from the original on November 14, 2016 ; accessed on January 16, 2021 .

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt: African Game Trails , p. 20.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt: African Game Trails , pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Stewart Edward White : The Rediscovered Land . Doubleday, Page & Company, Garden City, NY 1915 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Lot 289. White (Stewart Edward). The rediscovered country. In: Hensol, The Property of a Gentleman. Oct 24, 2012. Bonhams , October 2012, accessed January 16, 2021 .

- ↑ Rowland Ward : The sportsman's handbook to collecting, preserving, and setting-up trophies & specimens. Together with a guide to the hunting grounds of the world . Rowland Ward, London 1911, p. 8-9, 30-31, 79-87 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c Denis D. Lyell: African Adventure. Letters from Famous Big-Game Hunters . John Murray, London 1935, p. 44-48 .

- ↑ a b Anonymous: Naturalist Dead . In: The Gazette . Montreal November 2, 1925, p. 21 .

- ^ Shooting Estate for Sale: Hensol Estate, Kirkcudbrightshire. In: GunsOnPegs. Strutt & Parker, February 13, 2018, accessed January 21, 2021 .

- ↑ Lot 310. A collection of Boer War and First World War medals. In: Hensol, The Property of a Gentleman. Oct 24, 2012. Bonhams , October 2012, accessed January 16, 2021 .

- ↑ Anonymous: Obituary. Mr. RJ Cuninghame . In: Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society . tape 51 , no. 217 , October 1925, p. 425-430 , doi : 10.1002 / qj.49705121610 .

- ↑ Oldfield Thomas : On shrews from British East Africa . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History . Series 7th volume 14 , 1904, pp. 236-241 ( digitized version ).

- ^ C. Tate Regan : Description of a new fish of the genus Dentex from the coast of Angola . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History . Series 7th volume 15 , 1905, pp. 325 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Edmund Heller : Four new subspecies of large mammals from Equatorial Africa . In: Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collection . tape 61 , no. 22 , January 26, 1914, pp. 1–7 ( digitized version ).

- ^ RC Wroughton : Three new African Species of Mus . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History . Series 8th volume 1 , 1908, p. 255-257 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Oldfield Thomas: Two new Genera of small Mammals discovered by Mrs. Holms-Tarn in British East Africa . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History . Series 7th volume 18 , 1906, pp. 222-226 ( digitized version ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cuninghame, Richard John |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cunninghame, Richard John (misspelling); Cunningham, Richard John (misspelling) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Scottish explorer, big game hunter, natural history museum collector and photographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 4th July 1871 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stewarton , Ayrshire , Scotland |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 23, 1925 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Stranraer , Kirkcudbrightshire , Scotland |