Ungern-Sternberg novel

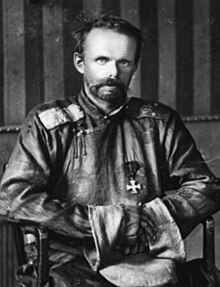

Baron Roman Nikolai Maximilian Fedorovich Ungern-Sternberg , Robert Nikolaus Maximilian Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg, ( Russian Барон Роман-Николай-Максимилиан фон Унгерн-Штернберг ., Scientific transliteration Baron Roman-Nikolai-Maksimilian fon Ungern-Šternberg ; and Roman Fyodorovich Ungern von Sternberg / Роман Фёдорович фон Унгерн-Штернберг * December 29, 1885 . jul / 10. January 1886 greg. in Graz , Austria-Hungary ; † 15. September 1921 in Novonikolajevsk , Soviet Russia ) was a Baron Baltic German origin in tsarist service.

He later changed his name from Ungern-Sternberg to Ungern von Sternberg . This was possibly for the reason that he wanted to counter assumptions about an alleged Jewish origin, since Sternberg was considered a classic Jewish name. When he translated his name into Mongolian , he changed it to mean Great Star Mountain. During the Russian Civil War, his opponents gave him nicknames such as Red Baron, Bloody Baron, White Baron or Black Baron.

As the commander of a sub-group of the White Army in the Far East of Russia, he occupied Outer Mongolia in early 1921 , after which he was awarded the title of Khan of Mongolia by the Bogd Khan . After about six months, his troops were crushed by the Red Army . Ungern-Sternberg himself was captured and executed after a short time.

Life

childhood and education

Roman von Ungern-Sternberg was born on January 10, 1886 in Graz as the third child of Theodor Leonhard Rudolf von Ungern-Sternberg and Sophie Charlotte, from the Hessian noble family von Wimpffen , and was baptized Lutheran . However, he was the first to survive infancy. His two older sisters died shortly after giving birth. The Ungern-Sternbergs are a German Baltic family who at that time owned possessions in the Baltic States . His parents divorced in 1890 and Roman stayed with his mother. Sophie Charlotte married another Baltic German nobleman in 1894, Oskar von Hoyningen-Huene , and moved with her son to his estate in Jerwakand .

Until he was 15, Roman was taught German at home before he was sent to the Nikolaus-Gymnasium in Reval . However, due to poor grades and resistance to the teachers, his parents were asked to take him away from school after a short time. His stepfather got him a place at the Naval Academy in Saint Petersburg , where his performance improved in the first year. But after he had to repeat the second year and still did not show the expected discipline, he was expelled from the academy in February 1905.

From the Russo-Japanese War to the First World War

Since he was now without employment or prospects, he volunteered for the Russian army to fight as a simple soldier in the Russo-Japanese War . At the front he only took part in a few combat operations and was promoted to corporal by the end of the war. Ungern-Sternberg spoke of the Japanese army and its success with respect and admiration .

Back in western Russia, he was briefly transferred to the Engineer Corps before entering the Pavlavsko Military Academy, where he completed cavalry training. It is there that von Ungern-Sternberg, who has since become Russian Orthodox, also came into contact with Buddhism and occult practices for the first time . After Ungern-Sternberg had completed the academy in the middle of his class, he applied for a post in a Cossack regiment and was assigned to the 1st Argun regiment of the Transbaikal Cossack Army in Dauria . The Argun regiment, which was stationed on the river of the same name in the Far East of Russia, was Ungern's first choice because it had good contacts to General Paul von Rennenkampff , one of his relatives, and he expected support from him. For reasons that were not finally clarified, he had to leave the Argun regiment again. It is considered possible that he dueled another officer while drunk. As a result, he joined the 1st Amur Regiment of the Amur Cossack Army . Due to general dissatisfaction with the inaction in the Far East, Ungern asked in a letter dated July 4, 1913 that he should be released and transferred to the reserve.

After he was allowed to do so, he started a journey through Mongolia on horseback, which led him to Urga , among other places . After trying in vain to be accepted into the local protection force of the Russian consulate, he succeeded in being accepted as an extraordinary captain at the consulate in Kobdo . Since he did not have many duties, he used his time, among other things, to learn the Mongolian language. However, in early 1914 he left Mongolia and returned to Reval. There he lived without a job until the outbreak of the First World War .

First World War

On July 19, 1914, Ungern was reactivated and assigned to a regiment from Nerchinsk , which was involved in the Russian invasion of East Prussia . After the fronts had largely come to a standstill, Ungern made a name for himself as the leader of reconnaissance missions right up to or even behind the enemy lines. For such an action he received the Georgskreuz 4th class on September 22, 1914 . Ungern fought in Poland and Galicia until October 1916 and was wounded five times during this time. Despite his bravery, he was barely promoted during this period, mainly due to his lack of discipline. After an incident on October 22, in which he insulted or beat an aide to the Russian governor of Chernivtsi while drunk , he was sentenced to two months' arrest.

After his release in January 1917, Ungern was briefly transferred to the reserve and sent to Vladivostok , but soon afterwards served on the Caucasus Front . Here he met Grigory Michailowitsch Semjonow again , with whom he had already befriended on the front in Poland and with whom he would bring a large area in the Far East of Russia under his control after the October Revolution . In the Caucasus, Ungern tried to build a regiment of native Assyrians who were hostile to the Turks , but this failed due to a lack of volunteers.

In March 1917, Ungern accompanied Semyonov to the east, where he wanted to recruit volunteers from the local Buryats for the war in the west with official permission . Following this, its track is lost until November of the same year.

After the October Revolution

Between Transbaikalia and Manchuria

Following the October Revolution, Ungern fought his way east to the town of Daurien near the border with Chinese Manchuria , where Semyonov had taken a position. From there, on Semyonov's orders, he crossed the border with some soldiers and a train and disarmed the approximately 1,500-strong Russian garrison of Manjur , which had turned against their officers. Then, as was customary in this early phase of the Russian Civil War , they were sent west by train. From then on, Manjur served as the base for the two of them, where they strengthened their volunteer force of only a few hundred men, which they called the Special Manchurian Division from then on .

From January 1, 1918, they advanced again from their base and occupied larger Russian areas along the Russian-Chinese border, which they were often only able to hold briefly due to their small number of men. Reluctantly, therefore, after a short time he switched to disarming the remaining Russian troops in Manchuria with a troop of Mongolian bargains . Since the Chinese viewed the Barguten as rebels and feared Ungern's increase in power, they took him and his troops prisoner at a fake banquet. Semyonov was able to extort them, however, by sending an armored train into Chinese territory.

From March to July 1918 the Special Manchurian Division tried again to occupy Russian territory, but had to withdraw deep into Manchuria after a heavy defeat on July 13. From August Ungern and Semjonow tried again. This time they were supported by Japanese equipment as well as the presence of Japanese troops and the skirmishes between the Bolsheviks and the Czechoslovak legions . This enabled them to occupy all of Transbaikalia and Semyonov declared himself the ataman of the region in Chita . Ungern was given command of the place Daurien and was also appointed major general by Semjonow .

Commander of Daurien

After his promotion, Ungern quickly began to emancipate himself from Semyonov. So he had new troops independently recruited and trained. At the same time, Ungerns and his men seem to have been brutalized. There were frequent looting of surrounding towns and trains passing through, as well as torture and murder of civilians. Jews were particularly at risk. While Ungern had few reservations about non-Russians in general, he blamed Jews for the October Revolution and the abdication of the Tsar as well as the civil war, which is why Jews passing through were often dragged off the trains and shot. From time to time he also seems to have planned a "cleansing" of all Jews from Russia in the aftermath of the white victory.

Although their rift continued to advance, especially since Ungern was increasingly annoyed by Semyonov's corruption, extravagance and friendliness towards Jews, the latter awarded him the Georgskreuz 4th grade again in March 1919 and appointed him lieutenant general , perhaps because Ungern cared about the many prisoners of war cared. As the civil war escalated further, both sides decided not to send disarmed prisoners back to enemy territory. The Bolsheviks captured under Semyonov's troops were often crammed into trains and brought to the Ungern area, which almost immediately left the majority of them murdered in the vicinity of Dauria and often left unburied. He was no better with his own people either. During 1919 and 1920, several epidemics of typhus and cholera passed through Siberia. Reluctantly, sick people who appeared unlikely to recover were shot immediately to prevent the disease from spreading further.

On August 16, 1919 Ungern surprisingly married a nineteen-year-old Chinese noblewoman with the Russian name Elena Pawlowna in Harbin . However, she did not accompany him to Daurien, but stayed in Harbin, where she received regular donations from Ungern.

In Mongolia

In the course of 1920 the situation of the White troops continued to deteriorate and after the death of Admiral Kolchak and the withdrawal of General Wrangel's troops from the Crimea , Transbaikalia was the last major area under white control. Da Ungern was aware of this was that their area would soon fall to the Bolshevik troops, he began to look for a place of retreat for himself and his troops.

Around this time he received a letter from the Mongolian 8th Bogd Gegen , who asked him and his troops for help. With financial and military support from the Russian Empire, the 8th Bogd Gegen had proclaimed the independence of Outer Mongolia in the course of the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 and proclaimed himself Bogd Khan . China did not recognize the secession , but granted the province certain rights of autonomy in the 1915 Treaty of Kjachta . During the October Revolution, the national Chinese took advantage of Russia's weakness: Bogd Khan was deposed and Outer Mongolia was once again administratively subordinated to Beijing on November 27, 1919 . Since the commander of the Chinese troops in Outer Mongolia, Xu Shuzheng, curtailed the power of the Bogd Khan, the latter was keen to find supporters for an overthrow. He found one in Ungern, who wrote a letter to his wife at the beginning of August 1920, in which he declared under Chinese law to divorce her. He then moved to the Mongolian border and occupied the small town of Aksha on August 15, before moving on to Mongolia and giving up his area in Transbaikalia.

His troop strength when he invaded Mongolia is not exactly known, but is believed to have not exceeded 1,500 men. With these fighters, Ungern decided on the night of October 26th to attack the town of Maimaicheng near the capital Urga . Most of the Chinese garrison troops were located here, so a victory there would have severely damaged the Chinese position in the country. However, Ungern's troops were outnumbered and Maimaicheng was well fortified. After a first setback, during which there was only minor fighting, he attacked again five days later, but was repulsed again. As winter was already on the horizon, Ungern decided not to dare any more action before the new year and retired with his troops to Zam Kuren, about 250 kilometers east of Urga, where he and his troops plundered surrounding settlements and monasteries. In order to maintain discipline, Ungern introduced a strict catalog of punishments that provided for severe corporal punishment or torture for the smallest offenses. He had deserters persecuted and chased to death.

In 1920 Ungern-Sternberg separated from Semjonow and established himself as an independent warlord. He considered the monarchy to be the only system of government that could protect Western civilization from corruption and self-destruction. He wanted to reestablish the Qing Dynasty in China and unite the Far Eastern nations under their rule. As a fanatical anti-Semite , he proclaimed in a manifesto from 1918 his intention to “ wipe out all Jews and people's commissars in Russia” and to put Grand Duke Mikhail Romanov , the younger brother of Nicholas II, on the Russian throne. Because of the turmoil of World War I, many Jews fled eastward from western Russia, where they had been forced to settle before the war. The troops from Ungern-Sternberg murdered all Jews they could get hold of, often in a cruel manner.

In January 1921, Ungern ordered several attacks on Urga, which initially failed with high losses. In February he finally managed to take the city. On March 13, 1921, an independent monarchy was proclaimed in Mongolia. Ungern-Sternberg brought Bogd Khan, the Jebtsundamba Khutughtu , nominally to the throne and was identified by him in return as the incarnation of the angry patron deity Jamsarang (Tib. Begtse ). Ungern-Sternberg was fascinated by Far Eastern religions such as Buddhism . His philosophy was a confused mixture of Russian nationalism with Chinese and Tibetan beliefs. In everyday life, his brief reign was mainly characterized by the murders and looting of his army. Besides Jews, the victims were also Russians who disagreed politically with him. The reign of terror of his army, requisitions and evictions quickly cost him all sympathy, even among the Mongols, who had initially viewed him as a liberator from the Chinese.

Defeat and death

In the spring of 1921 the baron attempted to attack Soviet territory in Buryatia . After initial successes in May and June, however, he was defeated in a counter-offensive. In the meantime, units of the newly established Mongolian Revolutionary People's Army (under Damdin Süchbaatar ) and Soviet Russian units had occupied Urga at the beginning of July . Ungern-Sternberg's people handed him over to the Red Army on August 21, 1921.

In a show trial led by Jemeljan Michailowitsch Jaroslawski , Ungern-Sternberg was sentenced to death by an express military tribunal . The process took less than seven hours. He was in Novonikolajevsk (now Novosibirsk ) shot . Allegedly, before his death, he is said to have swallowed his medal of the Order of St. George to prevent it from falling into the hands of the communists.

Trivia

- In the novel A Dream in Red by Alexander Lernet-Holenia , first published in 1939, Ungern-Sternberg made a brief appearance as a minor character.

- The Italian comic artist Hugo Pratt made Ungern-Sternberg a supporting character in 1974 in his graphic novel Corto Maltese in Siberia .

literature

- Sergius L. Kuzmin: The History of Baron Ungern. An Experience of Reconstruction . Moscow: KMK Sci. Press 2011, ISBN 978-5-87317-692-2 .

- SL Kuzmin. (Ed., Afterword). The Bloody White Baron and the Facts . - I order: fight and tragedy of Baron Ungern-Sternberg / B. Krauthoff. Crusade 1921: Dramatic Ballad / M. Head. Kiel 2011, pp. 309–331

- SL Kuzmin. How bloody was the White Baron? Critical comments on James Palmer's The Bloody White Baron . - Inner Asia, 2013, vol. 15, no 1, pp. 177-187

- Nick Middleton: The Bloody Baron: Wicked Dictator Of The East . Short Books, London 2001, ISBN 1-904095-87-9

- Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski : animals, people and gods . Strange Verlag 10810, 1923, ISBN 3-89064-810-X (The book describes the author's escape from Russia to Tibet and Mongolia and the encounter with the baron.)

- James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron: The Story of a Noble Man Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia . Eichborn (The Other Library), Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-8218-6234-7

- Vladimir Pozner : The White Baron . Verlag Volk und Welt Berlin (GDR), Berlin 1966 (biography / novel)

- Berndt Krauthoff: I command! Struggle and tragedy of Baron Ungern-Sternberg . First edition Carl Schünemann, Bremen 1938, second edition 1944

- Willard Sunderland: The Baron's Cloak. A History of the Russian Empire in War and Revolution . Cornell University Press, Ithaca-Lonodn 2014, ISBN 978-0-8014-5270-3

Web links

- Literature by and about Roman von Ungern-Sternberg in the catalog of the German National Library

- Baltic Historical Commission (ed.): Entry on the novel by Ungern-Sternberg. In: BBLD - Baltic Biographical Lexicon digital

- Dondog Batjargal: “Thinking is cowardice!” - The usurper Baron Ungern von Sternberg . MongoliaOnline, September 10, 2006

- Otto Magnus von Stackelberg : Genealogical manual of the Estonian knighthood , volume 1. Görlitz, 1930, p. 465

- Mario Bandi: Baron Ungern von Sternberg - Genghis Khan for half a year . Deutschlandfunk broadcast "Das Feature", August 18, 2017, production by Deutschlandfunk with Südwestrundfunk 2011 (pdf, 271 kB; also as a txt file )

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Ancestors of Roman, Baron von Ungern-Sternberg (1885-1921)

- ↑ Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 11.

- ^ A b Mario Bandi: Baron Ungern von Sternberg - Genghis Khan for half a year . P. 3 (pdf; 271 kB).

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, pp. 32-33.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, pp. 58 and 69.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 73.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, pp. 74-75.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 79.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 83.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 85.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 89.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 98.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Robert Arthur Rupen: Mongols of the Twentieth Century. Indiana University, 1964, p. 276.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, pp. 116-117.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, pp. 118-144.

- ↑ Simon Sebag-Montefiore : Baron Ungern-Sternberg, meteoric nutter. March 23, 2008, accessed November 5, 2008 .

- ^ CR Bawden: The Modern History of Mongolia , London 1968, pp. 216, 232 f.

- ↑ James Palmer: The Bloody White Baron. 2009, p. 229 ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ungern-Sternberg, novel by |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ungern von Sternberg, Roman Nikolai Maximilian; Ungern von Sternberg, Roman Fjodorowitsch |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Baltic nobleman and Khan of Mongolia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 10, 1886 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Graz , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 15, 1921 |

| Place of death | Novonikolaevsk , Soviet Russia |