Talharpa

Talharpa even tagelharpa ( Swedish , "Pferdeschwanzhaar- Harp ") or stråkharpa ( "String Harp"), Estonian hiiu kannel , Rootsi kannel ( "Swedish Kannel"), is a three- to four-string, with the arch painted lyre , which until the beginning of the 20th century in the folk music of the Swedish-speaking population in Estonia, especially on the island of Vormsi . The talharpa , which is closely related to the jouhikko , which occurs in the historical region of Karelia in eastern Finland , and is believed to be related to the crwth in Wales , has been restored in various forms since the 1970s. The Scandinavian strokes are considered a further development of older plucked lyres and, according to different hypotheses, go back to models in Western Europe ( crwth in Wales) or in the east (wing-shaped husle type in the settlement area of the Eastern Slavs ).

Origin and Distribution

Medieval north and north-east European lyres are likely models for plucked Baltic psalteries such as the Finnish kantele , which, in terms of instruments, belong to the fretboard-free box zithers and form a culturally related group of instruments in the Scandinavian countries and the Baltic States . In some early types with a slim body, a smooth transition can be seen between a lyre, the strings of which lead over the top of the body to a yoke attached to two rods, and a box zither, in the body of which there is an opening similar to the one space enclosed by the yoke construction. The distinction is not made according to the opening size or body shape, but based on the yoke construction. For the hypothetical origin of the talharpa , the elongated body shape, the playing technique when shortening the strings and the introduction of the bow are decisive criteria.

Body

The Baltic psalteries are considered to be national instruments as well as, in terms of their design, playing style and use, as the cultural heritage of a region between Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and Russia with roots that go back to pre-Christian times. Three dissemination theories of the Baltic psalteries are up for discussion : According to the first theory at the turn of the 20th century, the box zithers came from the Byzantines to the Baltic peoples through the mediation of the Slavs . According to a second theory from the period, mainly voiced by Finnish researchers, the box zithers are a very old national heritage of Finland. Curt Sachs (1916) added his “oriental” hypothesis of origin to both theories , according to which the zithers came to the Baltic States and Russia in the Middle Ages on an unspecified route from the Arab-Persian region. Of the three theories developed independently of one another, the thesis put forward by Sachs in particular that it was widely used formed the basis for later considerations. The assumption that the Scandinavian-Baltic culture was shaped by the Ukrainian cultural region further south during the hegemony of the Khazars also belongs in this context .

Archaeological finds from Novgorod on Lake Ilmen speak for the old relationship of the psalteries and lyres in the Baltic States and Russia , where slender lyres and similarly shaped zithers from the end of the 14th century were excavated from the 11th century. According to written sources, the slender box zithers, known as husle (Russian gusli ) in Eastern Slavic languages, probably had ten strings in the 12th century.

Playing technique

The yoke construction of the "Novgorod lyres" of the 11th and 12th centuries with a hole at the top end of the body allowed the player to hold the instrument, which was resting on his thigh and protruding upwards, with his left hand and at the same time with his fingers mute the strings from below while plucking them with his right hand. Due to the limited span of the hand, these lyres were equipped with a maximum of eight strings. Ilya Tëmkin (2004) draws a hypothetical line of development of the Slavic zithers, which he starts with a rotta in Western Europe ( red in England), one of the crwth- like pats, dated to the 6th century .

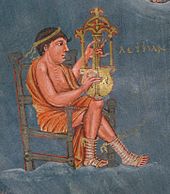

There is a formal relationship between the Novgorod lyres and the harpa lyres of the Germanic tribes in northern Europe, which are depicted in English and German manuscripts from the 7th to the 10th centuries. A depiction around 600 shows a narrow, six-stringed lyre with a large opening. A slightly smaller opening was found in a gusli excavated in Nerewski near Novgorod, 85 centimeters long , with nine strings and dated to the middle of the 13th century. A water bird head in relief near the tuning pegs is interpreted as a Finnish motif - with reference to a cosmogonic myth of the Finno-Ugrians , according to which a water bird built up the earth with mud from the seabed. Since the outer strings could not be tapped through the opening from behind, they must have been plucked empty as drone strings . In addition to the archaeological lyre finds in Russia, east of the Urals there is a lyre called nars-yukh ( nares-jux , "music wood") with a long rectangular body in the Ugric- speaking Khanty and Mansi . Curt Sachs (1930) mentions this perhaps the only remaining Asian lyre in connection with the Scandinavian string lyre, but is unclear about the connection.

The playing posture of the talharpa , vertical or slightly inclined to the left , in which the strings are shortened with the left hand through the opening from behind, is also shown in the Anglo-Saxon Vespasian Psalter , an illuminated manuscript from the 8th century. Like the Germanic lyres, the instrument has a long rectangular body with rounded corners and is covered with six strings. The same way of playing has been handed down from the lyres painted on ancient Greek vases.

At a certain time, the vertical playing position and fingering technique passed from below through the opening in the Baltic lyres - probably with intermediate stages, as some illustrations in manuscripts suggest - into the recumbent playing position of the psalteries, where the plucking technique does not use the opening from above can. Anglo-Saxon manuscripts from the 11th / 12th centuries illustrate the transition. Century, which show a player who, according to Ain Haas (2001), apparently mutes the strings from above with his fingers over the yoke while the ball of the hand is on the underside. In the Winchcombe Psalter (dated 1025-1050) a three-string plucked lyre and a four-string bowed lyre are shown in the same playing position. However, it cannot be ruled out, as Miles / Evans (2001) restrict, that both instruments were only held by the yoke with the left hand without grasping the strings. The four strings in the middle of the string could indicate a fingerboard underneath. A central neck is also to be assumed in a four-stringed lyre in the Durham manuscript from the beginning of the 12th century, although it is not possible to tell whether it was plucked or bowed. The aforementioned nine-string Novgorod lyre from the 13th century, the strings of which were only partially accessible from below through the small opening, also represents such a transition phase, the result of which was the kannel in Estonia .

When Estonian national consciousness began to develop under Russian rule around the middle of the 19th century, suitable national symbols had to be found. One of these introduced symbols is the legendary Vanemuine sage , who is portrayed playing a kannel while telling people about the melodious sounds of music. The narrative shows a certain resemblance to the role of Orpheus in Greek mythology. Contemporary images show Vanemuine dressed in a long flowing robe, following an ancient model, holding a lyre vertically in his hands. Apparently it didn't matter that this playing position corresponds more to the old Russian lyres and the Swedish talharpa , which is still used today , while the Estonian psaltery can be plucked horizontally on the table or on your knees with both hands from above.

String bow

According to Arabic and Chinese sources, the string instrument game originated in Central Asia. It is believed that strings on lute instruments were strung with rubbing sticks for the first time in Sogdia around the 6th century . Probably the oldest Chinese spring about the tubular zither yazheng struck with a stick dates from the 8th century . A string bow covered with horse hair for playing a long-necked lute with the Arabic name rabāb described in 10/11. Century the Islamic scholars al-Fārābī (around 872–950) and Ibn Sīnā (around 980–1037), who worked in the regions of Khoresmia and Sogdia. The one to two-stringed rabāb was then known in Central Asia as tunbūr and qobuz . In the palace of Hulbuk in southern Tajikistan there was a wall painting from the 10th century at the latest, showing two women; one of them strikes a long-necked lute with a bow. From their probable starting point in Central Asia, the strings reached Spain in the course of the 10th century with the Islamic expansion , where they appear on miniatures in two Mozarabic manuscripts from the 970s. At the turn of the 2nd millennium, strings were often depicted in Byzantine manuscripts . Al-Andalus and Byzantium were the starting points for the rapid spread of the bow in the 11th century across Western Europe.

Baltic strokes

The medieval round-bottomed lyre (bowl lyre) were considered to be German instruments and were called cythara teutonica , as it is called in a manuscript from the 12th century by the music historian Martin Gerbert (1774). Related to the cythara teutonica and the Anglo-Saxon lyres, which can be traced back to the 7th century, is a Norwegian lyre type, of which a specimen was found from the 14th century at the earliest with a rounded body, approximately parallel side arms and a straight yoke. Another late medieval type of lyre with a circular body and sloping arms can be seen on three Norwegian wooden reliefs and a baptismal font that deal with the Gunnar saga ( Thidrek saga ). In this type of lyre, the arms came together in the middle to form a kind of crown, which gave the instruments a venerable character.

The string veils developed from these lyres, plucked in a vertical position. The Welsh crwth is essentially a round-bottom lyre with a fretboard added in the middle to shorten the strings with the fingers like a neck lute. In the 9th century, lyres of the crwth type were still plucked and could hardly have been stroked with their flat web. With the spread of the bow in the 11th century people began to bow those lyres known in Old High German as rotta and, on an experimental basis, numerous other string instruments. It is unclear whether the central fingerboard of the crwth was added together with the introduction of the bow or was taken from plucked lyres known from two Bible illustrations from the 9th century. Bowed lashes without a fingerboard spread after the 11th century, especially to Scandinavia and Estonia as far as the Finnish-Russian border in the region north of Lake Ladoga . In addition to other forms, the talharpa type with a rectangular body box is mainly found in the north . In the Welsh Havod manuscript from 1605–1610 there is an unusual drawing of a three-stringed crwth without a fingerboard, which, apart from a wider body, comes closest to the talharpa shape. Otto Andersson (1923) put the crwth in connection with the talharpa . He propagated a spreading route for the patties, which leads from the Celts in the British Isles with the Vikings northwards to the Shetland Islands , to Scandinavia and to the Finns in the Baltic States. The names routsi (Swedish for “Sweden”), kannel, harpa and talharpa in Estonia and harppu in Karelia (Finland) prove that the cuddly lashes have taken on different forms in Scandinavia . As a second, less probable possibility, Andersson also mentioned the opposite direction, starting from a Scandinavian origin, whereby the historical-cultural relations of Scandinavia were the focus of interest. The Finnish musicologist Armas Väisänen (1923) questioned the western origin of the talharpa and also its connection with the kannel .

In his work, published posthumously in 1970, Andersson relativized his earlier positions and no longer completely ruled out other views in favor of an eastern or southern origin of the Scandinavian curses. The Swedish music historian Tobias Norlind , who, like Väisänen , dealt with the spread of the kantele in the 1920s and 1930s , highlighted the more numerous points of connection of the Scandinavian psalteries to the east (to the Russian gusli ) compared to the West and considered the strokes to be originally Scandinavian. In his review of Andersson's The Bowed Harp (1930), Francis Galpin criticized the constructed connection from the early medieval British Isles to Scandinavia because there were no usable Scandinavian sources up to the sculpture in Trondheim Cathedral. The stringed instruments mentioned in medieval legends, such as the Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar about the 10th century Norwegian King Olav I Tryggvason, contained in the Flateyjarbók collection , cannot be assigned to a specific form and playing style. For Galpin a southern influence on Scandinavia through German and French monastic orders, which were connected with Italian orders, was more obvious between the 9th and 11th centuries. Since the sculpture in the Cathedral of Trondheim is an instrument of church music, Andersson refers to the Welsh nobleman Giraldus Cambrensis , who tells of bishops and abbots around 1190 who wandered around and proselytized while playing on a harp.

A fragmentarily preserved wall painting in the middle of the 13th century in the Norwegian Røldal stave church, which is in need of interpretation, shows several standing figures who apparently belong to a music scene. A player is holding a five-string round lyre, of which only the upper half with the vertebrae indicated by dots can be seen. A horizontal line above the instrument may represent a bow. The form, which is unusually simple compared to other medieval representations, could be a lyre with a pear-shaped body played in the folk music of ordinary people, as it also occurred in Central Europe.

In Estonia, where there was already an old tradition of the plucked psaltery kannel , the spread of the talharpa was limited to the area in the west, conquered by the Swedes in the 13th century, and the islands off the coast, especially the island of Vormsi . For use as a string instrument, the psalteries only had to be changed insignificantly. In the case of the talharpa , the opening and fingering technique of the left hand from the underside were retained, and the small number of four strings in some Baltic lyres was also well suited for the bow. Only the bridge had to be rounded if the strings were to be bowed individually with the bow.

As a reaction to the missionary work of the Russian Orthodox Church , the Evangeliska Fosterlands-Stiftelsen ("Evangelical Homeland Society") sent Swedish missionaries to the Estonian Swedes from 1873 , who started a charismatic movement . The religious revival took on such extreme features in the 1870s that the island's village restaurants were replaced by houses of prayer, the traditional culture was largely displaced and the veils were collected as a work of the devil, brought to Hullo and burned there in a large fire. The few remaining lyre players saved the tradition into the 20th century, so that Otto Andersson was able to transcribe 30 melodies for talharpa on his first research trip to the island of Vormsi from 1903 to 1904 . At the beginning of the 20th century there were hardly any cultural activities on Vormsi apart from the offers of the Christian sects. This banned women from dancing and all other amusements of everyday life. It was only allowed to dance at weddings.

Research history

A stone sculpture in the octagon of the choir of the Cathedral of Trondheim , the Nidaros Cathedral , which was important for the discussion about the origin of the talharpa , was initially dated to the 12th century by Otto Andersson (1923) and other musicologists. More detailed investigations during restoration work in the 1960s revealed that the sculpture, which depicts a musician with a four-stringed string, was made in the second quarter of the 14th century. The choir was badly damaged in a fire in 1328 and then rebuilt in an English style. This means that the sculpture is still the earliest clear evidence of string veins in Scandinavia, while plucked lyres are identified by two finds from flat webs from the 8th and 9th centuries (made of amber , found in Broa near Halla on the island of Gotland ; from antlers, found in Birka , Sweden) had been considered occupied half a century earlier. Only one other bridge made of pine, which was found in the medieval excavation site Oslogate 6 in Oslo in 1988 and which is dated to the second quarter of the 13th century, seems to belong to a five-string string instrument because of its rounded top, on which five notches can be recognized to have. The first researcher to describe and depict the sculpture in 1904 was the Norwegian archaeologist Harry Fett. He was still completely unclear about the classification of the unusual instrument, while the Danish music historian Hortense Panum (1905) assumed, in view of the concealed upper end of the body, that the strings could only have been empty and, because of the bow position, only all of them could have been bowed at the same time. The Norwegian composer Erik Eggen recognized the type of instrument in 1923, which he related to the Icelandic box zither fiðla , the two strings of which were bowed with a bow. The finally accepted assessment that the sculpture is typologically one of the string veins played in Estonia, Sweden and Finland in which the left hand grips the strings from below through an opening that is not recognizable in the sculpture, was achieved by Otto Andersson in his dissertation from 1923.

The picture of an Estonian petting was published in 1854 in a picture book by the painter Ernst Hermann Schlichting , Costumes of the Swedes on the coasts of Ehstland and on Runö. The name tallharpa was first mentioned by the Estonian historian Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Rußwurm in his ethnographic study of the Swedes in Estonia, Eibofolke or the Swedes on the Esthland coast and on Runö, from 1855. Otto Andersson gave the instrument, which he first used in an in Stockholm given lecture about a trip to the Swedish settlement areas in Estonia, the name stråkharpa (Swedish, "string harp "). By this time the talharpa had almost been forgotten. Internationally, Andersson brought the instrument, which is practically unknown in terms of its shape and playing style, to the professional world in 1909 with the lecture Old Norse String Instruments at the II Congress of the International Music Society - Haydn Zentenarfeier in Vienna. Andersson's dissertation on talharpa was published in Swedish ( Stråkharpan: en studie i nordisk instrumenthistoria ) in 1923 and in English ( The Bowed Harp. A Study in the History of Early Musical Instruments ) in 1930 . In the course of the 20th century, other researchers discussed the origin and connection of Slavic, Baltic and Scandinavian box zithers and lyres, some of them controversial.

etymology

Rußwurm explains the word composition in 1855:

“The fir harp, tall-harpa, from tall, fir, or horsehair harp, from tâl, tâgel - horsehair, which can be shortened in combinations. The strings were sometimes made of twisted horse hair, as they are still used by children for this purpose. "

Andersson avoids the derivation tall , Swedish “pine wood”, with regard to the type of wood used for the body, and only considers tal von tagel , “horse hair”, from which the strings are made, to be convincing. The word component tal therefore only refers to the string material, not to the bow used, which is also made of horse hair. The name stråkharpa , "string harp ", introduced by Andersson , aims at the special way of playing and is a parallel word formation to Finnish jouhikantele ("string psalter"), from jouhi ("horse hair") and the word group kantele (corresponding in Estonia kannel , in Karelia kandele , in Latvia kokle and in Lithuania kankles ).

Harpa , Old High German harpha , which goes back to the common Germanic * harpō , is a certain type of instrument with today's spelling harp (English harp ). It is unclear whether Venantius Fortunatus , who in the 6th century mentioned the word for the first time in a musical context with the Latin barbarus harpa , meant a harp, a lyre or another instrument. The harp first appeared in Europe in the 8th century on the British Isles, but it was not until the late Middle Ages that harpa became a clear name for a particular form of harp. From the beginning of the 12th century the harp was considered the national instrument of Ireland.

The Germanic * harpō is derived from the Indo-European root (s) notch (h) for "to turn", "to curve". This means either the round shape of the instrument or the way it is played, associated with Latin. carpere , "pluck" - the strings are plucked with curved fingers. Further derivations also refer to the plucked playing style of the harp and other stringed instruments. In the Middle Ages, harper was understood as "someone who plays a stringed instrument". Andersson (1970) is now looking for evidence that harp could also have been used for string instruments and quotes the Danish linguist and folklorist Peder Syv (1631–1702) with the saying “En ond harper skraber altid paa den gamle streng” (“A bad harper always scratches / scrapes on the old string ”). In addition, the nyckelharpa (Swedish, "keyboard harp", in German "key fiddle") is a string instrument that has been known from illustrations since the 15th century at the latest, the strings of which are shortened using keys. An early form of this special fiddle with a melody string and a few drone strings was known as the enkelharpa ("single harp").

The Finnish name jouhikantele appears probably for the first time in Daniel Juslenius' Finnish-Latin-Swedish dictionary from 1745 in these two lines:

Candele, instrumentum musicum, harpa

Candelen jousi, plectrum, stråka.

According to Andersson, when the kantele is repeated twice , the lower line must refer to the deleted psaltery, although the Latin plectrum still needs explanation. Today, this is understood as a plate as an aid to plucking the strings, but Andersson finds individual references to the largely unaccepted view that the plectrum could also have referred to a bow. He also considers it an open question whether the string instrument mentioned in the old English poetry Beowulf (8th century) was plucked or bowed. After all, in the old Swedish dialect in Estonia the verb slå means “to beat”, so slå harpa stands for “to play the harp”, although the bowed lyre is meant. In Swedish, stryka means "to strike with a bow". This could explain why Juslenius translated the arc of the jouhikantele in Latin as plectrum in his dictionary . In any case, this was Andersson's idea of introducing the name stråkharpa .

Except for talharpa, stråkharpa and jouhikantele , the word combination can be found according to the pattern “Streichleier” (English bowed lyre ) in Scandinavian languages in the Norwegian word hair-gie or hårgie for a string instrument, as is the case with the - nameless - sculpture in Trondheim Cathedral is shown. The hair-gie ("hairy giga ", with giga to violin meaning "to move the bow back and forth", which also occurs in nyckelgiga , a variant of nyckelharpa ) was mentioned in the 17th century and disappeared in Norway before the 19th century. The word giga is related to gue , as a two-stringed box lyre was played on the Shetland Islands until the 19th century , a descendant of which came to Canada as tautirut to the Inuit . In Estonia, the talharpa was also called routsi kannel (“Schweden- kannel ”, meaning “foreign canal ”).

Design

The only difference between the Finnish jouhikko and the Swedish-Estonian talharpa is the shape of the opening. The three-string jouhikko has a long rectangular body with rounded corners and slightly bulged or tapered long sides. The narrow opening is at the upper end on the right long side, so that only one or two of the strings can be grasped from below with the fingers of the left hand. The talharpa has a much larger, roughly square opening with narrow symmetrical yoke arms on the sides, so that all four strings can be reached with the fingers from below. The body of the talharpa is either a long rectangular box with an integrated yoke or a yoke slightly protruding to the side and curved outward. A talharpa variant has a violin-shaped body including the f-hole in the domed ceiling , which is extended by an obliquely outwardly leading yoke construction. Otto Andersson (1923) mentions a third type with two elongated openings next to each other, but these are merely instruments that the Finnish musician Juho Villanen (1846–1927) made from Savonranta to save weight through the additional opening .

The talharpa is usually strung with four strings made of horse hair, gut or wire, which lead from a tailpiece to rear wooden pegs on the yoke. The crescent-shaped bridge with incisions to guide the strings is roughly in the middle of the top with one or two small sound holes cut into it. The round bow made from a thin branch is only loosely covered with horse hair, which is tightened with three fingers during the game.

Style of play

A flat bridge can be seen on the sculpture of the Trondheim lyre, which means that the bow was used to strike all strings at the same time. The player created the melody on the first string and on the other drone notes . In this traditional way of playing jouhikko and talharpa , the player reaches through the opening from below and touches the melody string with the fingertip or fingernail as if to create a harmonica tone. This method is based on such an old and stable tradition that it was also carried over to the string veils with the body of a modern violin. Schultz-Bertram (1860) reports on the playing style of the Finnish jouhikko used to accompany songs in the 19th century . On the two-string instrument, only the F-string was played with four fingers, not the C-string , which is a fourth lower: Touching the little finger gave the octave tone c, with the ring finger b, with the middle finger a and with the index finger g. The notes d and e of this octave were missing. He adds: “Such harp players have wart-shaped calluses on the back of their fingers.” Otto Andersson also found calluses on the fingers in talharpa players on Vormsi Island at the beginning of the 20th century. The talharpa was then played only by men, most of which went to the lake and had therefore strong rough hands.

According to Andersson, the four strings were tuned to fifths apart, for example e 2 –a 1 –d 1 –G. According to other authors, the interval between the third and fourth strings is unclear. In the talharpa , the upper two strings were used to form the melody and the others produced deep drone tones. The talharpa of the musician Georg Bruus on the island of Hiiumaa , of whom Otto Andersson made the first sound recordings with Estonian music in 1908, had three violin strings and the fourth probably a string made of twisted horsehair. The latter cannot be heard on the sound recordings, the other strings were tuned to a 1 –d 1 –G. Today the usual tuning in Estonia is e 2 –a 1 –d 1 –d 1 , that is, the two drone strings are tuned in unison. The folk song melodies for talharpa are mostly notated in D major .

When playing, the musician should ideally sit upright on a chair with right-angled knees and parallel legs. He positions the talharpa on the thighs parallel to the upper body, inclined to the left, and fixes it to the upper yoke arm with the thumb and forefinger of the left hand. The thumb always stays outside while the four fingers move between the yoke arm and the first string or between the first and second string. With your fingers it is possible to shorten the first, the second or both strings at the same time. In the playing technique preferred at the beginning of the 20th century, the index finger was always on the first string, if it was not needed for the second string, while the other fingers gripped the second string.

The bow is held in the right hand like a ballpoint pen. Middle finger and ring finger grip between the bow bar and the covering. A strongly curved bar and a variable tension of the hair make it easier to bow all four strings with a round bridge and favor springy, quick bow movements. These are necessary because the talharpa is a relatively quiet instrument, but it is mainly used in dance music. The musician therefore plays every note with a new bow stroke.

According to a description from 1922, the talharpa accompanied songs and dances, it was the most popular instrument at weddings and was part of the first ceremonial appearance of the bride in front of the wedding guests. No professional musicians had to be hired at the festivals, because there were always enough lyre players among the guests who played one after the other. During the entire Christmas season, the talharpa was often played at home with families, and in summer young people met to play the lyre together in the woods or pasture areas.

The best known talharpa players from the 19th and early 20th centuries include Hans Renqvist (1849–1906) and Anders Ahlström (1873–1959). Renqvist was a farmer and fisherman in the village of Borrby on Vormsi. In the 1870s he refused to destroy religious culture and continued to play the old melodies. Otto Andersson (1923) emphasizes his unusual but smooth grip technique of the left hand because he shortened the strings with the inside of the fingers. Ahlström was a blacksmith from Borrby. During the Second World War, like most Estonian Swedes, he was resettled to Sweden, where he lived in Stockholm.

Born in Stockholm, Stybjörn Bergelt (1939-2006) studied at the Royal Swedish Academy of Music and performed in several classical music orchestras. From the 1960s he became interested in folk music and in the 1970s he played the flute spilåpipa and talharpa in Swedish folk music groups . In 1974 he met the talharpa maker and musician Johannes Österberg from Vormsi, who taught him the old melodies and playing techniques. In 1976, Marie Selander, Styrbjörn Bergelt and Susanne Broms released the long-playing record Å än är det glädje å än är det gråt. It contains the first recordings of modern Swedish folk music with traditional instruments such as talharpa, nyckelharpa and sälgflöjt ( overtone flute , in Norway seljefløyte ). Bergelt's LP Tagelharpa och videflöjt from 1979, which received the award for the best Swedish folk music production of 1980, became particularly well known . In 1982 Bergelt became the first riksspelman ("state instrumentalist ") for talharpa , an annually awarded title for musicians. Bergelt was a role model for many Scandinavian musicians and researchers, who were inspired by him to deal with the talharpa .

Workshops and festivals for talharpa and other instruments of Estonian folk music are regularly held on Vormsi Island . The Estonian duo Puuluup also performed here, creating a mixture of modern Estonian folk music and pop music with electrically amplified talharpa , vocals and the use of loops . The Estonian song lyrics are often satirical and tell small, bizarre everyday stories. Puuluup also made a guest appearance at the 2018 Rudolstadt Festival , which focused on Estonia.

literature

- Otto Andersson: The Bowed Harp. A Study in the History of Early Musical Instruments . Mary Stenbuck (translator), Kathleen Schlesinger (editor), W. Reeves, London 1930 (Swedish original, dissertation: Stråkharpan: en studie i nordisk instrumenthistoria . H. Schildts, Helsingfors 1923)

- Otto Andersson: The Bowed Harp of Trondheim Cathedral and Related Instruments in East and West. In: The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 23, Aug 1970, pp. 4-34

- Elizabeth Gaver: The (Re) construction of music for bowed stringed instruments in Norway in the Middle Ages. (Master thesis) University of Oslo, 2007

- Ain Haas: Intercultural Contact and the Evolution of the Baltic Psaltery . In: Journal of Baltic Studies, Vol. 32, No. 3, Fall 2001, pp. 209–250

- Birgit Kjellström, Styrbjörn Bergelt: Stråkharpa. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- Hortense Panum: The Stringed Instruments of the Middle Ages. Their Evolution and Development . (edited and translated from Danish by Jeffrey Pulver) William Reeves, London 1939, pp. 232-239

- Hortense Panum: harp and lyre in ancient Northern Europe . In: Anthologies of the International Music Society , Volume 7, Issue 1, 1905, pp. 1-40 (included in the 1939 English edition)

- Janne Suits: The Reconstruction of Talharpa playing technique and tradition. (Master's thesis) Telemark University College , Rauland 2010

Web links

- Einar Selvik: MythicWorlds 2015 - Horsehair Bowed Lyre. Youtube video

- Michael J. King: Talharpa, 4 String Bowed Lyre with C tuning: CgCG. Youtube video

- Archival recordings (Georg Bruus, Mart Kaasen, Styrbjöen Bergelt), compiled by Janne Suits. Georg (Jurri) Bruus lived in Finland and had Swedish roots. Plays jouhikko . Recorded by Otto Andersson in Helsinki in 1908, published on two sampler CDs. Mart Kaasen (1869–1955) was a farmer and instrument maker in Kirimä village, Lääne County , Estonia. Start of the Estonian national broadcaster in 1936. Stybjörn Bergelt mentioned in the chapter on playing style .

- Puuluup . Audio samples on SoundCloud

- “Gnaal” - the bowed lyre (taglharpe) “Funeral march” . Youtube video (three-string self-made, whichdeviatesfrom the traditional tagelharpa shape)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ain Haas, 2001, pp. 209f

- ^ Curt Sachs: The Lithuanian musical instruments in the Kgl. Collection for German Folklore in Berlin. In: International Archive for Ethnography. Volume 23. EJ Brill, Leiden 1916, pp. 1-8, here p. 4 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Carl Rahkonen: The Kantele Traditions of Finland. (Dissertation) Folklore Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington, December 1989, Chapter 2: The Kantele Traditions of Finland.

- ↑ M. Khay: Enclosed Instrumentarium of Kobzar and Lyre Tradition. In: Music Art and Culture, No. 19, 2014, section Psalnery (gusli) .

- ↑ Dorota Popławska, Dorota Popłavska: String Instruments in Medieval Russia . In: RIdIM / RCMI Newsletter, Vol. 21, No. 2, Autumn 1996, pp. 63–70, here p. 66

- ↑ Gusli: Where? And When? gusli.by (various historical gusli types)

- ↑ Irene (Iryna) Zinkiv: To the Origins and Semantics of the Term "husly". In: Music Art and Culture. No. 19, 2014, pp. 33–42, here p. 39

- ↑ Ilya Temkin: Evolution of the Baltic psaltery: a case for phyloorganology? In: The Galpin Society Journal, January 2004, pp. 219–230, here p. 225

- ↑ Hortense Panum, 1939, pp. 93-95

- ↑ Ain Haas, 2001, p. 219

- ^ Curt Sachs: Handbook of musical instrumentation. (1930) Georg Olms, Hildesheim, 1967, p. 165.

- ↑ Ain Haas, 2001, p. 218

- ↑ Bethan Miles, Robert Evans: Crwth. 1. History and structure. In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ↑ Ain Haas, 2001, p. 223

- ↑ Ain Haas, 2001, pp. 211f

- ↑ Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Ed.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 26. De Gruyter, Berlin 2004, p. 162

- ↑ Harvey Turnbull: A Sogdian friction chordophone *. In: DR Widdess, RF Wolpert (Ed.): Music and Tradition. Essays on Asian and other musics presented to Laurence Picken . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1981, pp. 197-206

- ↑ Rainer Ullreich: Fidel. II. On the prehistory of European string instruments. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present, 1995)

- ↑ Werner Bachmann: Bow. I. History of the bow. 1. Origins. In: Grove Music Online, March 14, 2011

- ↑ Werner Bachmann: Arch. I. Beginnings of string instrument playing. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1994)

- ↑ Hortense Panum, 1939, pp. 91f

- ↑ Hortense Panum, 1939, pp. 96-100; Hortense Panum, 1905, pp. 14-17

- ↑ On the range of the word context rotta, known since the 6th century, see Marianne Bröcker: Rotta. 1. Terminology . In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1998); Hortense Panum, 1905, p. 34f

- ↑ Hortense Panum, 1939, p. 126f

- ↑ See Hortense Panum, 1905, p. 33

- ^ Marianne Bröcker: Rotta. 4. Fretboard Ribbons - Crwth . In: MGG Online , November 2016

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, pp. 7, 24

- ^ Gjermund Kolltveit: Studies of Ancient Nordic Music, 1915-1940 . In: Sam Mirelman (Ed.): The Historiography of Music in Global Perspective. Gorgias Press, New York 2010, pp. 145–176, here p. 168

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, pp. 10, 27

- ↑ See Elizabeth Gaver, 2007, p. 17

- ^ Francis W. Galpin: Review: The Bowed Harp by Otto Andersson . In: Music & Letters, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 1931, pp. 206f

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, p. 31

- ↑ Gjermunt Kolltveit: The Early Lyre in Scandinavia. A survey. In: V. Vaitekunas (ed.): Tiltai, Vol. 3, University of Oslo, Oslo 2000, pp. 19-25, here p. 23

- ↑ Elizabeth Gaver (2007, p. 26)

- ↑ Ain Haas, 2001, p. 224

- ↑ Ringo Ringvee: Charismatic Christianity and Pentecostal churches in Estonia from a historical perspective . In: Approaching Religion , Vol. 5, No. 1, 2015, pp. 57–66, here p. 58

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, pp. 6, 14, 22

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, p. 16f

- ↑ Gjermunt Kolltveit, 2000, p. 19f

- ↑ Birgit Kjellström, Styrbjörn Bergelt, 2001

- ↑ Elizabeth Gaver (2007, p. 21)

- ^ Ernst Hermann Schlichting : Costumes of the Swedes on the coasts of Ehstland and on Runö. Ten sheets. Leipzig 1854, panel VI

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, pp. 8-10

- ↑ See Carl Rahkonen: The Kantele Traditions of Finland . (Dissertation) Indiana University, Bloomington 1989, Chapter II. A Brief History of the Kantele .

- ↑ Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Rußwurm : Eibofolke or the Swedes on the coasts of Ehstland and on Runö . Second part. Fleischer, Reval 1855, VII Amusements, 5. Musical instruments, §305, 2. Die Tannenharfe, p. 118 ( limited preview in the Google book search - see also Otto Andersson, 1970, p. 11).

- ↑ Sylvya Sowa-Winter: Harps. I. The instrument. 1. Designations. In: MGG Online, November 2016

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, p. 12

- ↑ Gunnar Fredelius: nyckelharpa . In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, p. 13f

- ↑ Elizabeth Gaver (2007, p. 5)

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, pp. 21f

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, p. 25

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, p. 19

- ↑ Elizabeth Gaver, 2007, p. 123

- ↑ G. Schultz-Bertram: On the history and understanding of Estonian folk poetry . In: Baltic Monthly Magazine, Volume 2, Issue 1, Riga 1860, pp. 431–477, here p. 445 ( online at BSB )

- ↑ Otto Andersson, 1970, p. 26

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, p. 52

- ↑ Helen Kömmus, Taive Särg: Star Bride Marries a Cook: The Changing Processes in the Oral Singing Tradition and Folk Song in Collecting on the Western Estonian Iceland of Hiiuma, I . In: Folklore (Estonia), Vol. 67, April 2017, pp. 93–114, here p. 104

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, pp. 44f

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, p. 47

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, p. 51

- ↑ Janne Suits, 2010, p. 21

- ↑ Talharpospelaren Hans Renqvist från Wormsö, Borrby. (1903). finna.fi (photo from 1903)

- ↑ Janne Suits: Vormsi talharpa researcher Styrbjörn Bergelt. 2010

- ↑ Puuluup . Seto folk

- ↑ Filigree soundscapes from Estonia . Deutschlandfunk, January 4, 2019

- ↑ Jurri Bruus . Discogs

- ↑ Mart Kaasen. Anthology of Estonian Traditional Music. Estonian Literary Museum Scholarly Press, 2016