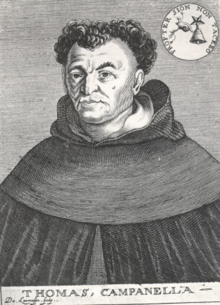

Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella (born September 5, 1568 in Stilo , Calabria as Giovanni Domenico Campanella , † May 21, 1639 in Paris ) was an Italian philosopher, Dominican , neo-Latin poet and politician.

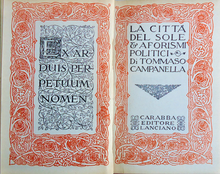

In 1602, Campanella designed in La città del Sole (Latin Civitas solis , German the sun state ) the utopia of a community with features of the Spanish universal monarchy , Catholicism, socialism (no private property) and parts of the Platonic state philosophy (e.g. community of women , rule the knower, the philosophers or the learned republic ).

Life

Childhood and youth in Calabria

Campanella was born on September 5, 1568 in Stilo in southern Calabria and seven days later was baptized Giovanni Domenico . Coming from the simplest of backgrounds, his father was a shoemaker, he was already noticed as a child because of his extraordinary intelligence and receptiveness as well as a phenomenal memory. His family planned a legal career for him, while Giovan Domenico was enthusiastic about the life and work of the great theologians Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas and finally joined this order , prompted by the sermons of a Dominican . He spent the probationary year in the Dominican convent in nearby Placanica and there accepted the religious name Tommaso . In the spring of 1583 he began his novice period at the Convento dell'Annunziata in San Giorgio Morgeto, studying Aristotelian writings on logic, physics and metaphysics as well as Arabic commentators. On the occasion of the appointment of the sixth Baron of San Giorgio, Giacomo II. Milano, Campanella made contacts with the noble family of the Tufo, from whom he was supported in later years. In the autumn of 1586 he was transferred to the Convento dell'Annunziata in Nicastro to continue his training in philosophy; in the summer of 1588 he moved to Cosenza .

Here he got to know for the first time the writing De rerum natura iuxta propria principia libri IX (Naples 1586) by Bernardino Telesio (1509–1588), who represented a natural philosophy independent of Aristotle based on his own epistemology , in which sensory experience plays a key role. The text of the Cosentine natural philosopher, which was directed against traditional scholastic views, inspired the young Tommaso, who retained his admiration for Telesio throughout his life. Campanella was no longer able to meet with Telesio in person, as Telesio died in Cosenza in October 1588. Possibly as a punitive measure for the insubordinate interest in Telesio's writings, Campanella was transferred to the remote Altomonte convent that same year. In the meantime he did not submit to the monastic seclusion in Altomonte, but made contacts with several local nobles, doctors and educated laypeople, through whom he probably came into contact with Hermetic and Kabbalistic writings for the first time . It was in this environment that his first major work, Philosophia sensibus demonstrata , was written, in which he defended Telesio's teachings. At the end of 1589 Campanella left the Altomonte monastery - without the permission of his superiors and allegedly accompanied by a mysterious Rabbi Abraham - and went to Naples , where he found accommodation in the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore, until he stayed in the city palace of Count Mario del Tufo in 1590 took and served there as a tutor . In Naples Campanella was able to devote himself to his own studies in the environment of learned personalities until he was arrested in May 1592 on a visit to the monastery of San Domenico on the charge of associating with demons ; later he was accused of having represented heretical views in the Philosophia sensibus demonstrata (Naples 1591) , which had meanwhile been printed . He was put on trial that ended with the requirement to return to Altomonte immediately.

Stay in Northern Italy

Campanella, however, did not submit to this judgment, but fled north on September 5, 1592 in the hope of getting a job at one of the Tuscan universities of Pisa or Siena . He stayed in Rome for a few weeks before going to Florence , where he was received by Grand Duke Ferdinand I on October 2nd . Although he was welcomed in a friendly manner and received financial support, Campanella was denied the job he had hoped for, so he left Florence on October 16 and moved further north. At the end of 1592, when Campanella was staying in the convent of San Domenico in Bologna , all the drafts of philosophical writings that had been written down in recent years were stolen from him by agents of the Inquisition . In January 1593 he came to Padua , where he stayed for a year. There he made the acquaintance of Galileo Galileo , with whom he maintained a lively correspondence throughout his life.

In the spring of 1594 Campanella and two friends were arrested in Padua by the Roman Inquisition on a pretext. On October 11th, they were transferred to the prison in Rome because on July 30th, friends of Campanella's fellow prisoners had initiated an attempt at liberation, which had failed. Against Campanella - among other things on the basis of the manuscripts stolen from him in Bologna - accusations of heresy were raised again, which, however, despite repeated torture, he did not admit and could partially refute through skillful defense. His imprisonment in Rome ended on May 16, 1595, when he publicly renounced his errors and was then under house arrest in the Dominican monastery of San Sabina in Abruzzo until the end of 1596 . After his rehabilitation , Campanella returned to Rome, but was arrested again on March 5, 1597 after denouncing a criminal named Scipio Prestinace , who was born in Stilo and sentenced to death in Naples. It was not until December 17th that Campanella was released again on the condition that it return to Calabria immediately.

Calabrian revolt

On the journey south, he stayed in Naples for a few weeks in the spring of 1598, where he visited numerous acquaintances from the time of his first stay, and then moved on to Nicastro . On August 15, 1598 he returned to Stilo in the Dominican convent of San Maria in Gesù. There he was embroiled in a conspiracy in the spring of 1599, which was directed against the Spanish rule in southern Italy and the Catholic clergy. The aim of the planned revolt - which was based on the support of the landed gentry, dissatisfied clergy and an Ottoman corsair - was to establish a fraternal community without private property, similar to Campanella later in the utopian book Der Sonnenstaat ( Civitas solis , dr. Frankfurt 1623 ) represented. Campanella supported the conspirators, probably out of a messianic sense of mission, by prophesying the imminent end of all secular rule in chiliastic sermons and mediating between the rival conspiratorial groups. However, the revolutionaries were betrayed to the Spanish on August 10, 1599, and Campanella was reported to the Inquisition on August 17. Although he fled immediately from the Stiles convent and went into hiding, he was tracked down on September 6th, shipped to Naples with 155 co-conspirators on November 8th and imprisoned there in Castel Nuovo.

Imprisonment in Naples

After the Inquisition had failed to extradite the clerics involved in the uprising to Rome, the high treason trial against Campanella began on January 18, 1600 in Naples , during which he made a full confession under the most severe torture and was therefore sentenced to death had expected. However, after he was tortured, he showed signs of severe mental confusion and started a fire in his cell on April 2, which almost killed him himself. During the first interrogation of his heresy trial on May 17, 1600, Campanella proved to be insane and, despite repeated torture, did not confess. Since a medical examination ordered as a result confirmed Campanella's madness, he could not be sentenced to death according to the legal opinion of the time. The death penalty was commuted to life imprisonment on November 13, 1602. By this time, Campanella's condition had improved so much that he was able to write several writings in the relatively mild detention, including Civitas Solis . However, his conditions of detention deteriorated in July 1604 when he was transferred to an underground dungeon in Castel Sant'Elmo and beaten in iron. He had to stay there until April 1608. Here he also wrote his book "Monarchia Messiae" in 1605 , in which the economic advantages of a European international community were presented.

"[...] If only one ruled, enmity, ambition and greed would cease in the world ... There would also be no more famine, since not all regions can be sterile at the same time. When some are wanting, others are in abundance. If all were under the guard of a single prince, then, he would order that food from the regions in which there was abundance should be brought to those in need, as was formerly from Egypt to Italy and from Africa to Sicily. There would be no more mortality or war or greed between foreign buyers and sellers because of lack of food. "

At the instigation of influential friends, he was transferred to the more lenient detention in Castel dell'Ovo. Here Campanella had another opportunity to write and receive visitors until he was brought back to Castel Sant'Elmo in October 1614. In the summer of 1616, Pedro, Duke of Osuna , took office as Viceroy of Naples. On a merciful whim, he released Campanella to the milder custody of Castel Nuovo, then sent him back to Castel Sant'Elmo and only had him transferred to Castel Nuovo in April 1618, where Campanella remained until his release. During his imprisonment several books by Campanella appeared on the basis of manuscripts brought to Germany by friends and visitors; so Prodromus philosophiae instaurandae (Frankfurt 1617), De sensu rerum et magiae (Frankfurt 1620), Von der Spanischen Monarchy (o. O. 1620 and 1623) and Realis philosophiae epilogisticae partes quatuor (Frankfurt 1623).

Release and time in Rome

On May 23, 1626 Campanella was released by the Spanish viceroy after almost 27 years in prison. This pardon was the result of Campanella's relentless struggle for release, which he had worked towards with countless letters to friends and influential figures - from local officials to Emperor Ferdinand II - as well as an immense writing activity that attracted him had assured influential circles. After his pardon, he lived in the Neapolitan convent of San Domenico for a month until the Roman Inquisition, having learned of his release, arranged for his arrest and deported him to Rome. He arrived there on July 8, 1626 and spent another two years under strict house arrest, while the Sant'Uffizio published his theological treatises Atheismus triumphatus (printed Rome 1631), Quod reminiscentur (printed Padua 1639) and Monarchia Messiae (printed Jesi 1633) Checked heretical content. On July 27, 1628, he was assigned a cell in the Convent of Minerva loco carceris ; in August he received his manuscripts back. Due to the influence of his Roman friends and his good relationship with Pope Urban VIII (1623-1644), Campanella was finally rehabilitated on January 11, 1629 after he had distanced himself from his writings published in Germany.

In the life of Campanella, who now primarily devoted himself to the publication of his writings, a change for the better occurred: on April 6, 1629 his name was deleted from the index , on June 2 he was given the title of magister theologiae and was authorized to do so Foundation of an academy granted with the aim of spreading Catholic teaching; he was even considered a candidate for a cardinal title. Meanwhile this meteoric rise aroused envy and resentment within the Curia . In 1629 the envious Campanellas launched the publication of a modified version of a manuscript he had written on Astrologicorum libri septem in order to discredit him with Pope Urban. In addition, there were ongoing disputes with the Inquisition about the religious conformity of certain passages relating to astrology in his writings. In the autumn of 1631 Campanella took a teaching position in Frascati with the Padri Scolopì and returned to Rome in January 1632, where he increasingly worked for the interests of the French King Louis XIII. entered in which he saw embodied the future of the Catholic faith.

Exile in France

Campanella's position in Rome was further weakened when, on August 15, 1633, the Dominican Tommaso, a student of Campanella, was arrested in Naples on charges of conspiracy against the Spanish government. In Naples the accusation has now been made that Campanella was the actual instigator of this conspiracy and had, among other things, ordered the viceroy and numerous nobles to be poisoned. When Pignatelli confirmed these allegations under torture - he withdrew them immediately before his execution on October 6, 1634 - the Spaniards emphatically demanded Campanella's extradition to the Kingdom of Naples . Campanella, who at that time was again in Frascati, therefore went to Rome in the autumn of 1634 to the Palazzo Farnese under the protection of the French ambassador. Possibly on the advice of Pope Urban himself, who wanted to avoid a confrontation with the Spaniards at all costs, Campanella left Rome disguised as a Franciscan on October 21, 1634 and went into exile in France. Via Livorno and Marseille, he went to Aix-en-Provence on November 1st , where he visited the scholar Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580–1637), with whom he had been in correspondence for a long time. From Aix he traveled on to Paris via Lyon, where he moved into the Dominican monastery in the Rue St. Honore on December 1st. Campanella was warmly received in France, since he had campaigned vehemently for the interests of the French monarchy in his most recent writings. He was received by Cardinal Richelieu on December 13, 1634 and even received an audience with King Louis XIII on February 9, 1635 . , who guaranteed him a state pension, which was paid out only hesitantly.

In exile in Paris, Campanella devoted himself primarily to the publication of his works - as he had done in Rome before. On May 2nd, he submitted several of his writings to the Sorbonne for examination and tried in numerous letters to Rome to prove that his works conformed to faith. He also supported French politics and advocated the conversion of the Huguenots . But even in Paris, Campanella was not immune to the hostility of his Roman opponents, who thwarted the publication of his writings, for example by banning the Paris booksellers from selling his books and trying to influence the Sorbonne against Campanella. Regardless of this, Campanella managed to publish numerous writings in France, among them Medicinalium iuxta propria principia libri septem (Lyon 1635), Metaphysica (Paris 1638), Philosophia rationalis (Paris 1638) and new editions of Atheismus triumphatus (Paris 1636), De sensu rerum (Paris 1636 and 1637) and Philosophia realis (Paris 1637). In the middle of September 1638 the now seventy-year-old Campanella was called again to the royal court to give the Dauphin a horoscope ; in this work, published as Ecloga (Paris 1639), he prophesies a bright future for the future Louis XIV . Tommaso Campanella died on May 21 of the following year and was buried in the Church of San Jaques. His grave fell victim to the turmoil of the French Revolution in 1795.

Works

- Philosophia sensibus demonstrata , 1591

- Monarchia Messiae , 1605

- Prodromus philosophiae instaurandae , 1617

- Apologia per Galileo , 1622

- La città del sole , 1602 (Latin Civitas solis , 1623; German Der Sonnenstaat , 1789)

- Atheism triumphatus , 1631, Paris 1636

- Metaphysica I-III , 1638

reception

Ernst Bloch dedicates his Leipzig lectures 1952–56 to Campanella with thoughts on the utopia of the social order, thus creating a link with modernity.

Modern editions

- Thomas Flasch (ed.): Philosophical poems . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-465-02870-8 (Italian text and German translation)

- Germana Ernst (Ed.): Sintagma dei miei libri e sul corretto metodo di apprendere (= Bruniana & Campanelliana Supplementi. Bibliotheca Stylensis 21). Serra, Pisa / Rome 2007, ISBN 978-88-622-7001-4 ( De libris propriis et recta ratione studendi syntagma )

- Luigi Firpo (Ed.): Tommaso Campanella: Poetica. Testo italiano inedito e rifacimento latino. Reale Accademia d'Italia, Rome 1944 (critical edition)

- Teresa Rinaldi (Ed.): Tommaso Campanella: Metafisica. Universalis philosophiae seu metaphysicarum rerum iuxta propria dogmata liber XIV. Levante, Bari 2000, ISBN 88-7949-234-9 (critical edition with Italian translation)

literature

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Campanella, Tommaso. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 895-897.

- Gisela Bock : Thomas Campanella. Political interest and philosophical speculation. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1974, ISBN 978-3-484-80069-4

- Ruth Hagengruber : Tommaso Campanella. A philosophy of similarity. Academia, Sankt Augustin 1994, ISBN 3-88345-333-1 .

- Thomas Sören Hoffmann : Philosophy in Italy. An introduction to 20 portraits. Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-127-8

- Michael W. Mönnich: Tommaso Campanella. His contribution to medicine and pharmacy in the Renaissance (= Heidelberger Schriften zur Pharmazie- und Naturwissenschaftsgeschichte , Vol. 2). Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-8047-1090-5

- Christoph Wurm: A place in the sun? - The Civitas solis des Tommaso Campanella. In: Forum Classicum 1/2013, pp. 39–45

- Maria Virnich: Campanella's epistemology and Fr. Bacon , Rhenania-Druckerei, 1917

Web links

- Literature by and about Tommaso Campanella in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Tommaso Campanella in the German Digital Library

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Works by Tommaso Campanella at Zeno.org .

- Tommaso Campanella in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Tommaso Campanella: La città del Sole by Karl Stas (Italian)

- Paul Lafargue : “Thomas Campanella. A critical study of his life and of Der Sonnenstaat ” , 1895

- The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Space Flight

- Tommaso Campanella - Der Sonnenstaat radio broadcast about this utopian novel with a dramatization of excerpts from it - in the online archive of the Austrian Media Library

Individual evidence

- ^ RH Foerster: Europe - history of a political idea. 1967, p. 125.

- ^ Lectures on the philosophy of the Renaissance , part of the Leipzig lectures 1952–1956; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1972, pp. 44-57.

- ↑ Maria Virnich: The epistemology of Campanellas and Fr. Bacon

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Campanella, Tommaso |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Domenico, Giovanni |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian philosopher, Dominican, theologian, poet and polymath |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 5, 1568 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stilo , Calabria |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 21, 1639 |

| Place of death | Paris |