Union Oyster House

| Union Oyster House | ||

|---|---|---|

| National Register of Historic Places | ||

| National Historic Landmark | ||

| Historic District Contributing Property | ||

|

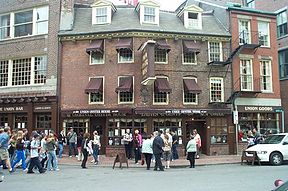

The house in 2008 |

||

|

|

||

| location | Boston , Massachusetts , United States | |

| Coordinates | 42 ° 21 '40.3 " N , 71 ° 3' 24.8" W | |

| Built | 1716-1717 | |

| architect | Unknown | |

| Architectural style | Georgian architecture | |

| NRHP number | 03000645 | |

| Data | ||

| The NRHP added | May 27, 2003 | |

| Declared as an NHL | May 27, 2003 | |

| Declared as CP | May 26, 1973 | |

The Union Oyster House (fully Ye Olde Union Oyster House ) is one of the oldest that are still in service restaurants of the United States at the Union Street in Boston in the state of Massachusetts . It was opened in 1826 and has since then continuously in addition to the eponymous oysters ( English oyster ) and other specialties of the cuisine of New England at. The building in which the restaurant is located was listed as a National Historic Landmark on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on May 27, 2003 . It has been a Contributing Property of the Blackstone Block Historic District since May 26, 1973 .

architecture

Outdoor areas

The house in which the restaurant is located consists of the main part, built between 1716 and 1717, and two adjoining extensions to the north and south, which were built in 1851 and 1916 and are now connected to the main part via wall openings. This middle building has an angled exterior facade that follows the transition between Marshall and Union Streets . The NRHP entry only relates to the main building.

The three-and-a-half-storey main house, resting on a stone foundation, has a mansard roof and was built in the style of Georgian architecture . The bricks on the Union Street side were laid in the Flemish Union , while on Marshall Street it is held in the English Union. Since the two sides also have other differences, it is assumed that they were either erected at different times, the building was only added to a floor after it was erected, or that it was simply a matter of cost-saving measures. In fact, the interior design suggests that the building was built as a whole and at the same time.

Below the roof there is a cornice supported by decorative consoles , which probably dates from the mid-18th century and was restored in the 1930s. In 1895 the original two dormers were first removed, but reinstalled in 1938 and a third was added. The doors and windows on the ground floor have windowsills, pillars and lintels made of granite , while those on the upper floors are made of sandstone that has been repaired with cement . The roof, originally covered with slate, is now made of asphalt - shingles . There is a continuous awning on the ground floor , while each window on the upper floors has its own. The illuminated lettering "UNION OYSTER HOUSE" on the roof can be seen up to Interstate 93 .

Indoor areas

Unlike most other buildings of this era, the building still contains a great deal of original furnishings. The semicircular oyster bar made of soapstone and oak or mahogany wood (there is disagreement on this point) and the table niches modeled on the market stalls are now unique in the entire United States. The soapstone counter was covered with copper plates by the 1940s at the latest , most likely to comply with hygiene guidelines. The nine stools arranged around the oyster bar consist of a cast iron frame with a wooden seat and are fixed to the floor. Not all of them have been preserved in the original.

The Italianate-style table niches are numbered, of different sizes and made of wood painted white. What they all have in common is a 1.2 m wide wooden table with wooden benches on the long sides. Along the inside walls of the bar you can see cast-iron columns of the Doric order , which were added in the course of the conversion of the original residential into a commercial building in the 19th century.

Historical meaning

The Union Oyster House is the oldest building within the Blackstone Block Historic District , one of the oldest brick structures in Boston and a rare example of Georgian architecture in the city. Before it was converted into a restaurant, Isaiah Thomas published the Massachusetts Spy newspaper from 1771 to 1775 . The Count of Chartres - later known as French King Louis-Philippe I - lived in a room above the then retailer during his exile in 1796 and taught French to prominent Boston citizens. The Union Oyster House is the oldest operating oyster bar in the United States.

Oyster culture in the United States

Oysters are prepared and served in a wide variety of ways and have a long history, particularly in the coastal regions of the United States. They are a popular source of protein, minerals and vitamins and are considered a healthy food because of their low cholesterol and high nutritional content.

In the 19th century, oysters were a typical fast food in the United States and were initially available raw or fried at many street vendors. The popularity of oysters led to the establishment of the first oyster bar in the United States in a New York cellar in 1763 . These USA-typical oyster cellars - oyster-serving restaurants below street level - in New York, Boston and Providence became the meeting point of the political and social elite, similar to the coffee houses in Europe. The oldest and best-known restaurants that still exist include the Boston Union Oyster House, Antoine's Restaurant in New Orleans , which opened in 1868, and the oyster bar in New York's Grand Central Terminal, which has been open since 1913 .

In large parts of the USA - but especially on the east coast - oysters are traditionally served on festive occasions such as Thanksgiving or Christmas. Plates, platters and cutlery specially designed for oyster consumption, such as the oyster knife , are popular collector's items today, especially the corresponding porcelain pieces from the collection of former US President Rutherford B. Hayes from the Victorian era .

Use as a residential building

In 1679 John Cosser bought the property for 50 pounds (approx. 9,100 pounds today) on which a small apartment building has stood since 1657 and where the Union Oyster House is now. After several changes of ownership, Phillips Chamberlain bought the building and land in 1741 for £ 1,800 (around £ 32,200 today) and sold it to Thomas Stoddard a year later for the same price. The house was known for Isaiah Thomas, founder of the American Antiquarian Society , from there published the Massachusetts Spy from 1771 until he had to flee the city to Worcester after the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 .

Stoddard's daughter Patience ran a non-food shop in the building with her husband Hopestill Capen , where they apprenticed Benjamin Thompson at the age of 16. Her son Thomas inherited the house and property in 1807 and continued the business until his death in 1819.

Conversion into a restaurant

The Union Oyster House was founded on October 7, 1826 by Hawes Atwood, whose family had been running oyster bars in Boston since 1818, under the name Atwood's Oyster House .

From 1842 to 1860 the restaurant was called Atwood & Hawes and from 1880 to 1916 Atwood & Bacon . Since this year the restaurant has been named Union Oyster House. In an advertisement by the oyster bar from 1854, oysters are offered at prices of 50 cents (today approx. 16 dollars ) per bushel or 1 dollar (today approx. 31 dollars) per gallon .

In 1933 the Union Oyster House was enlarged by a further 50 seats on the first floor converted for this purpose. In 1941 the kitchen was further expanded and renovated. Sawdust was used as flooring until 1946 . Sales figures fluctuated over time from 7,000 to 35,000 oysters per day. In 1951 a fire on the first floor was successfully prevented from spreading to the lower restaurant area. In 1970 the current operating family, Milano, acquired the Oyster House and expanded it in 1982 and 1995 by buying up the neighboring houses.

Known guests

The Union Oyster House has always attracted personalities from politics, business, music and the media. The most famous guests from politics include the US Senators Daniel Webster and Edward M. Kennedy as well as the US Presidents Calvin Coolidge , Franklin D. Roosevelt , John F. Kennedy and William Clinton . From the cultural area, the main ones are Paul Newman , Steven Spielberg , Luciano Pavarotti , Robin Williams , Billy Crystal , Sammy Sosa , Larry Bird , Ted Koppel , Dan Rather , Meryl Streep , Robert Redford , Al Pacino , Wayne Newton , Ozzy Osbourne and Alanis Morissette should be mentioned as regular guests. The restaurant's most famous local guest, however, was James “Pop” Farren, who ate oysters there almost every day from 1869 to 1934.

Others

Around 1890, Charles Forster observed Indians using pieces of wood to remove food particles from between their teeth and developed a machine for the production of toothpicks, which were previously unknown in the USA . However, since no restaurant could be convinced of his invention, he offered Harvard students payment for their meal if they asked for toothpicks after the meal, and chose the Union Oyster House as a test field. The restaurant responded quickly to the “wishes” of its customers and from then on offered toothpicks on small plates after dinner, which other restaurants in the city and later all eateries in the country took over.

Haverford College President Jack Coleman worked anonymously at the Union Oyster House for several months during his sabbatical . To this day, Frank Kellerher holds the record of 120 oysters eaten in one evening.

See also

literature

- Ralph Eshelman: National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. (PDF) United States Department of the Interior , National Park Service , May 21, 2001, accessed November 25, 2016 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Listing of National Historic Landmarks by State: Massachusetts. National Park Service , accessed August 14, 2019.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 4.

- ↑ cf. Eshelman, p. 5.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 6.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 11.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 12.

- ↑ cf. Eshelman, p. 13.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 14.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 15.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 16.

- ↑ a b cf. Eshelman, p. 17.