Valencia (ship)

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

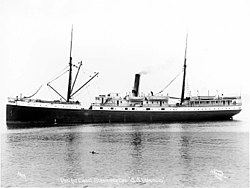

The Valencia was a passenger ship put into service in 1882 by the US shipping company Pacific Coast Steamship Company, which was used for liner services on the Canadian and American Pacific coasts . It carried passengers and cargo from California to Alaska and later to Seattle .

On January 22, 1906, in heavy seas and strong winds off Vancouver Island , the Valencia missed the entrance to the Juan de Fuca Strait and hit a reef . Because of the bad weather conditions and the churned sea, rescue ships could not do anything for the castaways . According to the official investigation report, 136 people were killed (including all women and children on board), but some sources also speak of 116 or up to 181 dead. 37 people survived, all men. The sinking of the Valencia is considered to be one of the greatest maritime disasters in the Pacific Northwest .

The ship

The 1,598 GRT iron- built steamship Valencia was built at the William Cramp and Sons shipyard in Philadelphia and put into service in May 1882. She had been commissioned by the Pacific Packing and Navigation Company together with her sister ship Caracas (1,200 GRT), which had already been commissioned in July 1881 . In 1902, the ship was bought by the Pacific Coast Steamship Company, a steamship company founded in 1877 to carry passengers and cargo from California to Alaska. The seat of the shipping company as well as the home port of the ship was San Francisco , but it was officially registered in New York .

She had three decks , four watertight compartments and three holds. A total of 181 people could be accommodated in six lifeboats , and three life rafts were also available for a total of 44 people. In addition, there were 368 life jackets . The ship did not have a false bottom and her bulkhead designs were relatively ineffective. During the Spanish-American War in 1898, the ship was leased by the US government to bring troops to the Philippines . After the war, the Valencia returned to its Pacific route.

On April 27, 1905, the last annual major inspection of the ship took place in Seattle . The Valencia operated from its commissioning to the usual route on the Pacific coast, but was transferred to the San Francisco – Seattle route in early January 1906 to replace the City of Puebla passenger steamer , which was subjected to repairs in San Francisco. On January 6, 1906, two weeks before leaving for their last voyage, there was another, smaller safety inspection.

Downfall

On Saturday, January 20, 1906 at 11.20 a.m., the Valencia left San Francisco on her second voyage to Seattle on a clear day. She was under the command of Captain Oscar Marcus Johnson and had 108 passengers (46 first class, 62 second class) and 65 crew members, a total of 173 people, on board. The Valencia followed her usual course north, staying between five and 20 miles from the coast. When the steamer passed Cape Mendocino on the coast of Humboldt County , the westernmost point of California, in the early morning hours of January 21, the weather deteriorated drastically. Strong south-easterly winds came up, it began to rain heavily and haze spread on the surface of the water . Visibility deteriorated rapidly. The ship was at the time 190 miles north of San Francisco. Astronomical navigation for precise positioning was not possible due to the bad weather conditions, so the senior officers were forced to perform dead reckoning.

To get to Seattle in the US state of Washington , the Valencia had to enter the Juan-de-Fuca-Strait , a strait about 20 km wide , north of Cape Flattery , and then circumnavigate Vancouver Island to the east. Captain Johnson assumed before 21.30 pm the Umatilla- Lightship reach. On Monday evening, January 22nd, visibility was so poor that no land could be made out on board the Valencia . The strong wind and churned seas caused the ship to miss the entrance to the Juan du Fuca Strait by about 20 miles. Just before midnight, at 11:50 p.m., the Valencia hit the Walla Walla reef eleven miles southeast of Cape Beale on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island .

Captain Johnson immediately turned the engines back to full power to get his ship off the rocks. As soon as the Valencia was back in the water, machinists from the engine room reported that a great deal of seawater was entering the hull in several places. To save the ship from sinking, Johnson let the engines run forward again and thereby drove the Valencia back onto the cliffs to set her aground. The steamer was only about 50 meters from land, but the sea between her and the shore was very stormy and turbulent. The panic and confusion on board was great. After the ship stopped, the lights on board went out. Passengers and crew members were trapped on the swaying ship, as the storm caused the lifeboats to sink after the freeze . Despite the captain's orders, six boats were launched, but all of them crashed: three overturned while lowering and threw more than 50 passengers into the sea, two others capsized in the water and one disappeared without a trace.

Many passengers were washed overboard by the high waves. Women and children in nightgowns were seen trying to climb the ship's rigging to get to safety. Desperate passengers had meanwhile intoned the chorale Closer, my God, to you . On the morning of January 23rd, the steamer began to slowly break apart, tossed to and fro by the waves.

Rescue attempts

Twelve men managed to swim ashore, three of whom were subsequently dragged away by the waves. The other nine found a telephone cord in the trees on the bank, which they followed into the forest. There they found a radio booth from which they called for help by wireless telegraph . In the meantime, a group of crew members had cast off in another lifeboat with the order to find a safe landing site and from there to connect the ship with a rope. When they came ashore, they saw a sign that read "Three Miles to Cape Beale". The original plan was dropped and the men set out on foot to the Cape Beale lighthouse , where they arrived after two and a half hours and informed the duty officers of the accident.

The news of the Valencia accident had already reached Victoria ( British Columbia ) by radio , from where three ships immediately set off for the scene of the accident. The largest was the passenger steamer Queen , which was accompanied by the salvage ship Salvor and the tug Czar . The Queen , under the command of Captain NE Cousins, reached the Valencia on the morning of January 24th, but no rescue attempts could be made because of the still stormy seas. The Salvor and the Czar left for Bamfield to prepare a rescue operation across the country.

On board the Valencia , which was still sitting on the rocks, two life rafts were launched, but hardly anyone wanted to board . The passengers assumed that the rescue ships would take them on board shortly. In the meantime another ship had arrived on site, the City of Topeka under the command of Captain Gibbs, which belonged to the same shipping company, but it too could not penetrate the Valencia . She managed to rescue 18 men from one of the rafts. The other raft , which had four men on board, was washed ashore and found by North American Indians .

When the rescue team that wanted to rescue the castaways from land arrived on the cliff, they saw that only parts of the Valencia were sticking out of the water and that many passengers were clinging to the rigging and superstructure. Their attempts to attach ropes to the wreck failed. Around 11:30 a.m. on Wednesday, January 24, 36 hours after being stranded, a large wave tore the remains of the Valencia off the rocks and washed them into the Pacific. None of the people who remained on board could be saved. Some passengers were thrown against rocks and killed, others were driven into the open sea by the waves and drowned.

A total of 136 people were killed in the sinking, including 40 crew members and 96 passengers. 37 people survived, including 25 crew members and twelve passengers. All 17 women and eleven children on board were killed. Only 33 bodies were recovered. Captain Johnson was also among the fatalities. It was reported about him afterwards that he stayed on the bridge to the end and prayed aloud for his passengers. To date, the sinking of the Valencia is one of the worst shipping accidents in the Pacific Northwest.

Investigation and consequences

Just a few days after the sinking, on January 27, the United States Marine Inspection Service began investigating the disaster. It was chaired by Captain Bion B. Whitney and Captain Robert A. Turner. During the hearings, which ended on February 13, almost all of the 37 survivors were heard. On March 17, 1906, the final report was submitted to the Canadian Department of Commerce .

The incumbent US President , Theodore Roosevelt , commissioned a further investigation, on the one hand to clarify how the tragedy could have happened and on the other hand how to avoid such accidents in the future. The commission called 60 witnesses, gathered over 30 pieces of evidence, and recorded 1,860 pages of testimony. The final report of this Federal Trade Commission , chaired by Lawrence O. Murray, Assistant Secretary of Commerce of the United States , was published on April 14, 1906.

The final result was that errors in the ship's navigation and the bad weather had led to the disaster. It was recorded that the life-saving appliances were in good condition and sufficient, but that rescue exercises were not carried out on board. The rescue ships had done everything in their power to help the Valencia's passengers .

The high loss of life was also attributed to the fact that life-saving equipment was limited on the Vancouver Island coast. The Roosevelt Report called for a lighthouse to be built between Cape Beale and Carmanah Point and a shoreline path equipped with lifeguards for castaways. It was also recommended that the nearby towns of Tofino and Ucluelet should be equipped with surf boats that could rescue people from the water in emergencies. For this purpose, the city of Bamfield should also have a steam-powered rescue ship. The Canadian government took immediate action. In 1908, the Pachena Point lighthouse began work and in 1911 the West Coast Trail was completed.

Trivia

In 1933, 27 years after the Valencia sank , one of the ship's lifeboats, number 5, was found in Barkley Sound Bay . The boat was in surprisingly good condition and the paint was also well preserved. The name of the boat is now in the Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria.

In connection with the dramatic end of the ship, there were various ghost stories about the Valencia after the sinking . Five months after the accident, a local fisherman claimed to have seen a Valencia lifeboat with eight skeletons in a cave by the water . However, a group that set out to search for the cave could not find it. In 1910, The Seattle Times reported a couple of sailors who claimed to have seen a ghost ship resembling the Valencia near Pachena Point .

The Canadian poet and writer Agnes Lockhart Hughes wrote about the sinking of the Valencia the poem The Wreck of the Valencia , which she personally lectured at a memorial service.

Graveyard of the Pacific

The Valencia went down in a sea area known as the Graveyard of the Pacific ("Cemetery of the Pacific"). Due to unpredictable currents, suddenly emerging fog banks and the often treacherous sea, numerous accidents have occurred in the area. An estimated 2,000 ships and 700 lives have already been lost in the graveyard. The areas around the sandbank Columbia Bar, Cape Cape Flattery , the cliffs on the west coast of Vancouver Islands and the Juan de Fuca Strait are particularly dangerous .

The Valencia is one of the most famous and most publicized wrecks in the region. Other major shipping accidents in the graveyard include:

- The passenger ship Clallam sank on January 8, 1904 off San Juan Island on Juan de Fuca Strait in a storm, killing 56 people

- The ferry Dix collided with the schooner Jeanie on November 18, 1906 in Elliott Bay off Seattle, killing 45 people

- The Coastal Liner Sechelt capsized on March 24, 1911 off Church Point in the Juan de Fuca Strait in heavy seas and sank, there were no survivors

literature

- Baily, Clarence H. The Wreck of the Valencia . In: Pacific Monthly , March 1906 issue

- Calkins, RH The Hero of the Valencia Disaster . In: The Marine Digest , Issue No. 20, January 27, 1951

- Gibbs, James A. Shipwrecks off Juan de Fuca . Binfords & Mort, Portland, 1968

- Newell, Gordon R. The HW McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest . Superior Publishing, Seattle, 1966

- Rogers, Fred. More Shipwrecks of British Columbia . Douglas & McIntyre, 1992

- Neitzel, Michael C. The Valencia Tragedy . Heritage House, Surrey, 1995

- Wilma, David. Graveyard of the Pacific: Shipwrecks on the Washington Coasts . Essay, September 2006

Web links

- Detailed and illustrated description of the last trip

- Entry in the Miramar Ship Index

- "Tragic Loss of the SS Valencia: America's Titanic" (multi-page presentation)

- Article about Valencia on a Seattle city website from July 17, 1997

- Discussion about the Valencia in the Encyclopedia Titanica (including the poem by Agnes Lockhart Hughes)

- Mention on the 100th anniversary of the sinking on the website of the Queen Anne Historical Society

- MANY PERISH IN WRECK OF FRISCO STEAMSHIP ( New York Times article, Jan. 24, 1906)

- Article about the Valencia in the Virtual Museum Canada

- Full report of the commission of inquiry