Grænlendingar

Grænlendingar ( Icelandic "Greenlanders") were Scandinavian settlers who, coming from Iceland , settled on the island of Greenland from the year 986 . The settlements existed for around 500 years until they were abandoned for reasons that have not yet been fully clarified. The Grænlendingar were the first Europeans to begin exploring and temporarily colonizing North America .

It is believed that they developed a language of their own called Greenland Norse - not to be confused with the Eskimo-Aleut Greenlandic language .

history

prehistory

The Scandinavian expansion in the early Middle Ages was essentially due to two peculiarities of society. The then applicable law of inheritance among the Nordic peoples favored the firstborn son . When new arable and pasture land in Scandinavia could no longer be developed due to the relatively dense settlement, the only alternative was to build up their own property outside of the established structures. This was promoted by the high value that personal daring, willingness to take risks and physical resilience had in the local society. With the advances in shipbuilding from around the 8th century, suitable aids were also available to travel to the edge of the known world and to found settlements there.

The springboard for the colonization of Greenland was the colonization of Iceland . According to current estimates, 50,000 to 60,000 people lived in Iceland in the 10th century. A stable social structure had been established and good land was in legally secure possession. This consolidated land distribution, several years of bad harvests and a famine provided the reason to look for new settlement areas in the 970s.

Discovery of Greenland

Around the year 900, the navigator Gunnbjörn Úlfsson on a voyage from Norway to Iceland had strayed far off course and was driven with his ship on a western coast, probably in the area of today's Cape Farvel on the southern tip of Greenland. He had sighted icebergs , skerries and a desolate, inhumane landscape and therefore did not go ashore.

Eiríkr inn rauði ( Erik the Red ) acquired the Haukadalr farm on the Icelandic Breiðafjörður (Breidafjord; near today's Búðardalur in northwest Iceland) by marriage . The Althing sent him into exile for three years because of a fatal argument . The Landnámabók reports that in 982 he sailed with the outlaws Þorbjörn (Thorbjörn), Eyjólfr (Eyjolf) and Styrr (Styr) from the Snæfellsnes peninsula to the west in order to find Gunnbjörn's land. He reached the Greenland coast at "Miðjökull" (Midjökul; presumably today's Ammassalik in East Greenland), sailed from there south and circled Cape Farvel to find suitable land for settlement. He spent the first winter on an island off the south coast. After the Íslendingabók he already found traces of settlement there, which probably came from the Neo-Eskimo culture ( Skrælingar ).

In the following spring Erik sailed further north and entered a large fjord, which was named after him Eiríksfjörðr (Eriksfjord) (today Tunulliarfikfjord). At the end of the fjord, at a geographical latitude of about 61 °, he founded his farm Brattahlíð (Brattahlid) in the climatically most favorable area of Greenland. First he built a rectangular wooden hall. From there he undertook several exploratory trips that took him across the Arctic Circle to today's Disko Bay . The following year he sailed back to Iceland.

Here he gathered around 700 people whom he was able to convince to find lush pastures and the best conditions for settlement in "grassland", as he called the newly discovered land. The name chosen is euphemistic, but probably not entirely unrealistic. Because warming has also been proven in other ways during this period and is called the “ Medieval Warm Period ”.

The group sailed with 25 ships, of which, according to the description in the land register, only 14 reached the Greenland coast. The farms built by the first settlers on Eriksfjord formed the core of the eastern settlement.

Settlement and Consolidation of Society

Icelandic sources suggest that at least three other fleets with settlers reached Greenland in the following 14 years. About 500 km north of the Ostsiedlung, the Westsiedlung was built, but always had to exist under less favorable conditions. Around the year 1000 practically all climatically relevant areas of Greenland were settled. The colony approached its maximum population of 5000 to 6000 people.

There is much to suggest that in the early days of the colony Erik the Red held a leadership position. In contrast to Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands, however, Greenland was never politically organized as a cohesive state. An official leader is not to be proven for the following period. But the chief in Brattahlid can be said to have a special influence due to its central location and tradition. Since the 14th century Brattahlid made the Lögsögumaður , the law speaker ; however, it is not certain whether he performed the same function as in Iceland.

Although Erik the Red was traditionally not a Christian, the colony was soon Christianized. However, the Íslendingabók and the Grœnlendinga saga (saga of the Greenlanders) unanimously report that when Herjólfr (Herjolf), one of Erik's companions, was first colonized, a Christian from the Hebrides was on board. After the saga of the Greenlanders, Erik's son Leifr ( Leif Eriksson ) brought Christianity to Greenland around the year 1000. The Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar (story of Olaf Tryggvason ) in the Heimskringla reports the same . According to this report, he already had a priest with him. The Grœnlendinga saga does not mention him, but the fact that the wife of Erik the Red Þórhildr (Thorhild; after the baptism Þjóðhildr - Thjodhild) had a little church built some distance from the courtyard makes the very early presence of a priest seem credible. Except for a few small amulets , there is no archaeological evidence of the practice of pagan rituals; on the other hand, the remains of Christian churches and chapels have been excavated on numerous farms, including the church of Brattahlíð , to which the report in the Grœnlendinga saga about the little church of Thjodhild fits exactly. These churches were built by the respective landlord, and he was therefore - initially - also entitled to the dues to be paid by the parish. Until the 11th century, Greenland was under the Archdiocese of Bremen . The Grœnlendinga saga reports that the colony sent Einarr Sokkason to Norway in 1118 to induce King Sigurðr jórsalafari (Sigurd the Jerusalem Driver) to assign Greenland its own bishop. The first Greenlandic bishop was Arnaldr from 1126, whose presumed bones were excavated under the floor of the church of Gardar (other assumptions go to Bishop Jón Smyrill, † 1209). Several other bishops followed, for whose care important benefices were established. By 1350 the church owned the largest yard and about two-thirds of the best pastureland.

The last Greenlandic bishop died in 1378. A successor was also appointed for him, but he refused to give up the relatively comfortable living conditions in Norway and to travel to inhospitable Greenland. He was represented there by a vicar. However , he and his successors did not renounce the Greenlanders' tithing .

The lack of an overriding power meant that local rulers found themselves in an endless series of conflicts. In order to end the constant quarrels, the Greenland colony submitted to the Norwegian crown in 1261. King Hákon Hákonarson had also been working towards this step for a long time. In return, the colony received the promise of regular shipping connections. But this step also resulted in a Norwegian trade monopoly. In 1294, King Eiríkr Magnússon of Norway issued letters of privilege to local merchants for the Greenland trade. All others, namely the Hanseatic League , were forbidden to sail to Greenland. Apparently there was regular trade with one or two "state" ships per year until the second half of the 14th century. The Kalmar Union turned out to be fatal for traffic with Greenland ; for the remote outpost was of little interest to the Danish royal family and trade dried up. To what extent the Hanseatic League, defying the Norwegian monopoly, filled the gap still needs to be investigated.

Downfall

Sometime before 1350 the Greenland western settlement was abandoned. Ívarr Bárðarson (Ivar Bardarson), a priest from Norway, sailed from the east to the west settlement in 1350, but found no more living there. He suspected that the Skrælingar had captured the settlement and killed all the inhabitants. As a result, King Magnus II of Sweden and Norway sent a Swedish-Norwegian expedition across the North Sea to West Greenland in 1355 to help the oppressed settlers. Captain Paul Knudson reached the western settlement, but did not find the Norwegians who had fled in the meantime on the North American mainland either.

The last Norwegian merchant ship reached Greenland in 1406. Captain Þórsteinn Óláfsson (Thorstein Olafsson) stayed on Greenland for a few years and married in 1408 in the church of Hvalsey Sigríðr Bjarnardóttir (Sigrid Björnsdottir). This report in the Nýi Annáll is the last written record from people who have been to Greenland. Later there are reports in the various Annálar about observations of people on Greenland (see the translated sources ). After that, no contacts with the rest of Europe can be traced back to the sources. In view of the archaeological findings, it is doubtful whether they actually broke off.

In 1534 the Icelandic Bishop Ögmundur von Skálholt claims to have seen people and sheep pens on the west coast. There is a contemporary report in the city archive of Hamburg, which tells of the journey of a Kraweel from the Hanseatic city to Greenland. The captain Gerd Mestemaker reached the west coast in 1541, but he could "not come to any living person" there.

In 1585 the English explorer John Davis passed Greenland while searching for the Northwest Passage and made contact with the Inuit in the area around what is now Nuuk , but found no living Europeans. The whalers , who occasionally passed by in the 16th and 17th centuries , also saw no signs of the presence of descendants of the Icelandic colony. Between 1605 and 1607, the Danish-Norwegian King Christian IV financed three expeditions to clarify the fate of the colonists, who did not find the settlements.

There are various, sometimes controversial, theories about the sinking of the Grænlendingar. From today's perspective, a combination of various unfavorable factors is likely, the interaction of which destabilized the society of that time so that its survival was no longer assured after the 15th century.

- The Inuit culture Thule , which originated in Alaska around 900 AD, spread to the east on the Arctic coast from 1000 AD and replaced the older and backward culture of Dorset II . The Inuit who lived in the far north of Greenland were also affected or displaced by this development after 1100. The bearers of the Thule culture also opened up the previously uninhabited coasts of Greenland in the following centuries. The entire Arctic coast can be considered populated from around the 15th century. Encounters between the Grænlendingar and the Eskimo cultures are certain. There is also evidence of (occasional?) Conflicts, but the scope and nature of relationships with the Inuit are controversial. It cannot be ruled out that the Inuit overran the declining settlements and killed the residents. This is assumed at least for the western settlement, but is no longer the sole reason for abandoning the eastern settlement.

- From the 15th century, the climatic conditions deteriorated dramatically. Between 1400 and 1850 there was the so-called “ Little Ice Age ” with temperatures that were around 0.5 to 1 ° C lower in Greenland than they are today. It is understandable that such a sharp drop in temperature had fatal effects on a peasant society that was always at the limit of climatic livelihoods anyway. Frequent crop failures and ongoing famine may have gradually led to the colony becoming extinct. The findings of Poul Nørlund in Herjulfsnes cemetery are instructive in this regard. The skeletons from the late 14th and early 15th centuries are significantly smaller than the older finds unearthed in the Brattahlid cemetery. The men are seldom taller than 1.60 m, the average women only 1.40 to 1.50 m. A conspicuously high number of child burials indicates a high child mortality rate. Most skeletons have defects, for example crooked backbones or pelvic constrictions, and rachitic symptoms are common. The anthropologist Niels Lynnerup rejects the theory of extinction through malnutrition. The signs weren't enough. The archaeologist Jørgen Meldgaard found the remains of a well-stocked pantry and utensils that do not indicate malnutrition in the western settlement.

- The geographer Jared Diamond is of the opinion that soil erosion through overgrazing, lack of raw materials such as iron and wood, war with the Inuit, a conservative attitude of the Grænlendingar, which prevented them from adopting techniques of the Inuit (e.g. harpoons) , and climate change interacted. For example, dental analyzes of ovicaprids (sheep / goats) from the western settlement also speak in favor of overgrazing.

- The decline in trade relations cut the settlement off from the supply of essential raw materials, especially wood and iron . The Greenlanders were not able to fill this gap with their own ships because there was a lack of suitable materials for shipbuilding. The archaeologist Niels Lynnerup contradicts this: The funeral customs would have resembled those in Iceland well into the 15th century. And Jette Arneborg points out that clothing fashion followed that in the rest of Northern Europe until the end of settlement, which rules out total isolation.

- The thesis was temporarily held that the settlers had survived and mixed with the Inuit ( Fridtjof Nansen ). However, this theory has now been refuted by genetic analysis.

- In 1359 Bergen raged and between 1408 and 1414 in Iceland plague epidemics . Since trade with Greenland was carried out exclusively via Bergen and Trondheim and there was constant contact with Iceland, the Danish-Norwegian historian Ludvig Holberg concluded that the plague had also reached Greenland and thus contributed to the colony's decline. A mass grave was found near Narsarsuaq; However, whether this can be considered conclusive evidence of an epidemic is still open. In any case, the necessary conditions for the spread of a plague epidemic were probably lacking.

- The opinion was also expressed that pirates , namely the Vitalienbrüder , had murdered the last settlers and plundered the farms. A papal letter from 1448 and other rather dubious sources were cited for this. There is historical evidence that the Vitalien Brothers attacked and robbed the rich and well-defended city of Bergen in 1429, a raid to Greenland would have been less risky but also less rewarding. However, there are no written records of such a company. This approach is no longer pursued today.

- Some researchers are also considering (mass) emigration to America. So far there is no evidence of this. But the archaeological evidence suggests that there was no particular “Greenlandic” group feeling, so a gradual return migration is most likely today.

- The latest research and archaeological excavations by Danish scientists showed that the Grænlendingar had adapted well to the deteriorating climate by switching to seal fishing . Seals made up up to 80% of their diet. The herds of cattle were replaced by more frugal goats and sheep. The abandonment of the settlements is due to several factors: The abandonment of the traditional way of life in favor of that of the Inuit has weakened the identity of the settlers. Walrus teeth and seal skins were rarely in demand; therefore hardly any merchant ships came to the island with urgently needed timber and iron tools. Many young and vigorous residents left Greenland until the settlements were apparently abandoned as planned. The Black Death and rural exodus had depopulated large parts of Iceland and Norway, so that there was enough better settlement land available for the resettlers.

Settlements

In the literature, a distinction is made between two Icelandic settlements in Greenland - the larger eastern settlement (Eystribyggð) around today's Qaqortoq and the smaller western settlement (Vestribyggð) around today's city of Nuuk - both of which are located on the West coast of Greenland. Due to the Gulf Stream , the climate in these areas is significantly more favorable than in all other areas of Greenland. Between the two settlements there were still some scattered farms (near today's Ivittuut ), which are summarized in some publications as "middle settlement ". In contrast to the Inuit, who as hunters and fishermen needed direct access to the open sea, the agriculturally active Grænlendingar settled in the protected areas at the end of the long fjords . The climatic conditions there were more favorable for agriculture and grazing. According to current estimates, the total number of Icelanders in Greenland was a maximum of 5000 to 6000 people, most of whom lived in the eastern settlement. So far, the remains of around 300 farms, 16 parish churches (plus several chapels), a Benedictine monastery of St. Olaf near Unartok and a monastery on the Tasermiut Fjord are known.

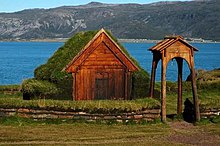

The excavations in Brattahlid, but especially that of a homestead near Narsaq in the 1950s and 60s, give a good idea of the appearance of the settlements. The typical Grænlendingarhof consisted of a group of buildings on a larger area. It included stables for sheep, goats, cattle and - at least in the early days of the settlements - also pigs and Icelandic horses . There were also a number of barns, storehouses and farm buildings, from the findings of which one can conclude that textile production and dairy farming were predominantly carried out there. The main building was a conglomerate of interconnected rooms with a central building in the style of a long house , which was built on a foundation made of field stones alternating from peat sod and stone layers. The construction method was possibly adopted by the Inuit, because it was already known to the Eskimos of the Saqqaq culture (2400-900 BC). The simple roof structure consisted of driftwood (in some courtyards also of whale bones) and was covered with sod. A practical and artfully executed water supply and drainage system consisting of covered canals irrigated and drained the houses. The stables were also built from stones and turf. The cowshed always consisted of two interconnected rooms, the cattle barn itself with the dwellings and a larger feed chamber. The 1.5 m thick outer wall made of field stone was preceded by a wall several meters thick made of sod and earth for cold insulation. Astonishing are the occasional stone blocks of up to 10 tons in weight. The more important courtyards had a church or chapel and a bathhouse, similar to a sauna . Many farms also had "Saeters" in the distance, huts that were only used in the summer months for haymaking on remote pastures, a system similar to that of the Mayen meadows in the Alps.

East Settlement

The traditional name is misleading insofar as this settlement is located on the west coast of Greenland. However, it can be explained by the fact that their location at the end of the Eriksfjord, which expands to the east, required a longer journey from the coast to the east. The fjord is surrounded by rolling hills and characterized by numerous small and tiny islands. In the sheltered areas in the interior of the fjord, subarctic vegetation flourishes profusely in summer. The climate is still the mildest in Greenland today.

The eastern settlement is the oldest Grænlendingar settlement, comprised 192 farms and is located in a protected location at the end of the approximately 100 km long Eriksfjord. It goes back directly to a founding of Erik the Red. Fertile soils and rich pasture grounds made livestock possible. The Norwegian clergyman Ívarr Bárðason reported around the middle of the 14th century that even apples are said to have ripened in favorable years.

The largest and richest farms in Greenland belong to the eastern settlement.

Brattahlíð (Qassiarsuk)

Erik's farm Brattahlíð (Brattahlid) was the most important of the eastern settlement; it was excavated in the 1930s. An extensive complex with several interconnected residential buildings contained an approximately 25 m long hall, which served as the central living and meeting room. Two stable buildings housed the considerable livestock of a total of 50 cows. The dimensions of the boxes and the bone finds suggest that the cattle, with a shoulder height of around 1.20 m, were much smaller than today's. The foundation walls of several storehouses and farm buildings as well as a forge have also been preserved.

On the site, somewhat separated from the main complex, was the church of Brattahlíð , surrounded by an earth wall , of which only sparse remains have survived today (a reconstruction was built on the site a few years ago) and the church built by Thjodhild today applies. A cemetery with 144 skeletons has been excavated around the church, 24 of them children, 65 men, 39 women and 16 adults, whose gender could not be determined. About half of the men - quite a few over six feet tall - were between 40 and 60 years old. Many of them showed clear signs of arthritis and badly worn teeth. There is a mass grave in the cemetery with the remains of 13 people. These skeletons, as well as some others, show traces of sword and ax blows, which suggests not uncommon armed conflicts.

Gardar

Garðar (Gardar, today Igaliku ) lies on a fertile plain between the Eriksfjord and the Einarfjord and was the bishopric of Greenland. The largest agricultural property - even before Brattahlid - was owned by the church. The Cathedral of Garðar , consecrated to St. Magnus (according to other sources, St. Nicholas) , of which not much more than the foundation walls have been preserved, was 27 m long when completed at the beginning of the 13th century and 16 m wide in the cross choir including the side chapels. It had greenish glass windows and a bell tower with bronze bells, both of which were particularly valuable imported goods.

To the south of the church and connected by a tiled path, the bishop's residence was followed by a large building complex with several rooms and a hall measuring 16.75 × 7.75 m. The farm had a well and two large stables - the larger of which was 60 m long - with space for 100 cows, as well as several storehouses and farm buildings. This also included a forge in which traces of lawn iron ore were found. Connected to the property was a harbor with a boat shed directly on the Einarsfjord. In total, the complex comprises around 40 larger and smaller buildings, which alone proves the outstanding position Gardar occupied in the Viking society of Greenland.

Hvalsey (Qaqortukulooq)

The Church of Hvalsey is the best preserved building of today Grænlendingar. The simple, rectangular church interior was built around 1300 on a gently sloping slope not far from the fjord. As usual with old churches, it is east-west oriented . The roughly 1.5 m thick walls are artfully piled up from largely unworked natural stone. It is also possible that clay was used as a mortar. There is evidence that the exterior walls were originally whitewashed. The church has a low doorway with a rectangular window above it in the west facade and a larger window with a Romanesque arch in the east facade. Another door and two slotted windows are in the south wall. The window niches widen inwards like a funnel - a construction method that is also known from early churches on the British Isles. The gables are about 5 m high. Inside the church, apart from a few wall niches, no decorative elements can be seen. The former clay soil is now covered with a sod. The roof, which is no longer preserved, was originally made of wood and sod. The appearance corresponds to that of churches in the Faroe Islands , Orkney and Shetland Islands . Since the church buildings in Iceland and Norway were usually built of wood, this could be an indication of regular contacts between the colony and the British Isles. The church was the site of the last recorded incident in Greenland. A magnificent wedding took place there on September 14, 1408. The guests came from Iceland in 1408 and drove back in 1410.

From the surrounding courtyards, only sparse remains of residential buildings, stables, warehouses and storehouses are preserved; some of them have not yet been archaeologically examined.

Western settlement

The western settlement is about 500 km north of the eastern settlement in the vicinity of today's capital Nuuk in a less favorable climatic location. It was smaller and more modest and comprised around 90 farmsteads near today's Kapisillit settlement . In the west settlement, the "Hof unter dem Sand" (The Farm beneath the Sand) was excavated in the 1990s when skeletal remains became visible through the impact of waves . The evaluation of the data obtained in the course of an emergency excavation has not yet been completed, but it already provides a picture of the living conditions, which were significantly less favorable than in the Ostsiedlung.

The northern hunting area (Norðrsetur)

The northern hunting area played an essential role in the supply of food and the procurement of export goods. It should have been located at a geographical latitude of 70 ° in the area of today's Disko Bay . No permanent settlements of the Vikings are known north of the Arctic Circle, but written sources document annual hunting expeditions in the summer months. These ventures served the indispensable supply of meat as a food supplement, but also the procurement of ivory walrus , narwhal teeth, seal and polar bear skins, eiderdown , musk ox horns and caribou antlers. Norðrsetur could be reached by rowed boats in 30 days from the western settlement and in 50 days from the eastern settlement.

In this area there were also (regular?) Encounters with the Inuit of the Thule culture . Already from 2500 BC Settlements and hunting grounds of the Eskimo cultures in the Disko Bay (Sermermiut) are proven.

There is also clear evidence of occasional expeditions further north. In 1824 three stone marks were discovered on the island of Kingittorsuaq at a latitude of 73 °. In one of them a twelve centimeter long rune stone from the early 14th century was set, which names the date April 25 (the year is not given) and the three members of such a hunting expedition.

Way of life, trade, economy and food supply

The living conditions must have been similar to those in Iceland. Of the 24 child skeletons at Thjodhilds Church in Brattahlid, 15 were infants, one child was three years old, one was seven and four were eleven to twelve years old. Child mortality in Iceland was of a similar magnitude in 1850, even if one takes into account that not all dead newborns were buried at the church. The small number of deceased older children indicates good living conditions. Neither do any contagious diseases appear to have raged on a large scale. Of the 53 men outside the communal grave, 23 have reached the age between 30 and 50 years. There were only three of the 39 women and only one got older. There are also some from a group whose age over 20 could not be determined. The average height of the men was 171 cm - not a few measured 184–185 cm - that of the women 156 cm; this is more than the average in Denmark around 1900. All of them had good teeth, albeit significantly badly worn, and there was no tooth decay. The most common disease that could be detected in the skeletons was severe gout in the back and hips. Some were so crooked and stiff in the joints that they couldn't be laid down for a funeral. However, gout was widespread in Scandinavia during the Viking Age . Other diseases can no longer be identified today. The custom of the burial place had also been adopted from Norway and Iceland: in the north the female skeletons predominate, in the south the male skeletons. The greater the distance from the church, the more superficial the burial, from which it can be inferred that the distance of the grave from the church depended on the social status of the deceased.

The Greenland economy was based primarily on three main pillars: livestock, hunting and animal trapping, which supplied food and trade goods in varying proportions. The farms were separated from each other and in fact self-sufficient because of the large pastures required for cattle breeding .

The Norwegian textbook Konungs skuggsjá (Königsspiegel) reports in the 13th century that Greenland farmers mainly ate meat, milk ( Skyr , a sour milk product similar to our quark), butter and cheese . The archaeologist Thomas McGovern of the City University of New York used piles of rubbish to study the diet of the Scandinavian people of Greenland. He found that the carnal diet consisted of an average of 20 percent beef, 20 percent goat and sheep meat, 45 percent seal meat, 10 percent caribou and 5 percent other meat, with the proportion of caribou and seal meat in the poorer western settlement being considerably higher was than in the Ostsiedlung. Obviously the inhabitants also caught fish regularly; for swimmers and weights from fishing nets were found in the settlements.

Finds of hand mills in some courtyards of the Ostsiedlung suggest that a small amount of grain was also grown in favored locations. Mainly, however, it is likely to have been imported. The Königsspiegel reports that only the most powerful bonds (with farms in the best locations) have grown some grain for their own use. Most of the residents have no idea what bread is and have never seen one.

An essential supplier of vitamins was "Kvan" ( angelica ), which was brought to Greenland by the settlers and can still be found in gardens there today. Stems and roots can be prepared as a salad or vegetables.

The constant lack of wood should prove to be problematic. Around the turn of the millennium, only small dwarf birches and willows grew in Greenland , which could only be used to a limited extent as construction timber. The driftwood that washed up with the Gulf Stream was of poor quality. Therefore, lumber was an important (and expensive) import.

Iron implements and weapons were another important import item. No ore deposits were known in Greenland at the time of the Vikings. The already not very productive smelting of lawn iron ore quickly reached its limits due to the lack of suitable fuels (charcoal), so that the settlements were almost exclusively dependent on imports. An example shows how dramatic the iron shortage was: During excavations in the western settlement in the 1930s, a battle ax was found. It was modeled on an iron ax down to the smallest detail, but made from whale bones.

Besides drying, curing was the only way to preserve meat. This required salt, which also had to be imported.

The settlement also had a number of export goods that were very popular in the rest of Europe:

Because of the special climatic conditions, the Greenland sheep produced wool that was very fatty. The fabrics and garments made from them were in great demand because of their water-repellent properties. The items of clothing excavated in Herjolfsnæs correspond to those found on inner-European frescoes from the same period and were of a higher quality than those found in the rest of Scandinavia from this period.

The white gyrfalcons of Greenland, which reached the Arab countries on branched trade routes, were a very popular export . The narwhal tusk , which was believed to neutralize poison in European royal and princely courts, was paid even higher . It was assumed that the snail-like and pointed horn came from the legendary unicorn .

Walrus ivory was also very popular for artistic carvings at royal and princely courts; however, the value declined when the Arabs were able to supply elephant tusks from Africa in the late Middle Ages. Resilient and durable ship ropes were made from walrus skins.

Contacts with the Inuit

Both archaeological finds and written evidence (of the Nordmanns) prove that there were encounters between the Eskimo cultures and Scandinavians. It is controversial whether these encounters were regular trade relations or only occasional - possibly warlike - contacts. Oral traditions of the Inuit (only written down in the 18th and 19th centuries) report several times of armed conflicts. Relics of the Scandinavians, especially objects made of iron, have been discovered several times in archaeological sites of the Inuit. It is not known whether these were obtained through peaceful exchange or robbery.

The Eirikssaga ( Eiríks saga rauða ) tells of a skirmish that the Icelander Karlsefni fought with the Skrælingar in which two of Karlsefni's men and four Inuit were killed. In the Icelandic Gottskálks Annálar it is recorded for 1379 that Skrælingar hailed from the Grænlendingar, killed 18 men and enslaved two servants. Whether and to what extent the Inuit contributed to the demise of the Grænlendingar culture is controversial.

History of discovery and research

The first tangible reference to Icelandic settlements in Greenland - besides the well-known written documents - is likely to be the discovery of the English captain John Davis, who found a gravestone with a Christian cross in the eastern settlement in 1586. Further grave and skeleton finds by whalers followed.

However, the memory of the “blond men” in Greenland was never gone. In the 16th and 17th centuries there were some half-hearted attempts to contact the colony, particularly to bring the apostate Grænlendingar back "into the bosom of the Church". In Denmark and Norway the story circulated that the Grænlendingar could no longer bake hosts due to a lack of grain and now allegedly worshiped the cloth with which the last host was covered. These attempts failed mainly because the settlements, in a wrong interpretation of the name Eystribyggð , were searched for on the east coast of Greenland.

When Pastor Hans Egede, who came from Lofoten , heard about it, he set out to proselytize the Christian settlers who had supposedly apostate from the faith. When he anchored in Godthaab, today's Nuuk, in the summer of 1721, he found some remains of the western settlement without identifying them as such, but no living Europeans. However, he stayed in Greenland and instead began proselytizing the Inuit. But it was not until Gustav Frederik Holm's trips to Julianehåb in 1880 and Daniel Bruhns' investigations at the same place in 1903 that the systematic archaeological investigations began. It was also Holm who, with his discovery of Ammassaliks on the east coast on his women's boat expedition in 1884, finally proved that Eystribyggð could not be found there.

In 1921 the Danish government sent an archaeological expedition to Greenland under the leadership of Poul Nørlund. He excavated a cemetery at Herjulfsnes farm and found items of clothing in excellent condition, which are now part of the National Museum in Copenhagen (reconstructions in the Museum of Nuuk). The first scientific excavations in Brattahlid and Gardar as well as in Sandness in the western settlement are to be owed to him.

From 1940 onwards, Leif Verbaek carried out extensive excavations near Vatnahverfi in the eastern settlement.

As part of the "Nordic Archaeological Expedition" in the 1970s, various interlinked researches on the history of Greenland - both the Grænlendingar and the Eskimo cultures - took place.

The latest project is the research of the “courtyard under the sand” in the western settlement by the Danish Polar Center with the participation of the University of Alberta , the evaluation and publication of which is still ongoing (as of November 2006).

See also

Literature sources

- swell

- Landnahmebuch (Landnámabók), book of the settlement of Iceland, originally from the 11th century, oldest surviving version from the 13th century, in English translation here: [1] . German: Das Besiedlungsbuch in: Iceland's settlement and oldest history . Exercised by Walter Baetke. Düsseldorf 1967.

- Erikssaga (Eiríks saga rauða), the earliest version handed down in the Hauksbók from the 14th century, in an English translation of the Gutenberg project here: [2] . German: Greenlandic stories . In: Greenlanders and Faroese stories. Exercised by Felix Niedner. Düsseldorf 1965.

- Greenland saga (Grænlendinga saga), the earliest version passed down in the Icelandic Flateyjarbók from the late 14th century. German: Greenlandic stories . In: Greenlanders and Faroese stories. Exercised by Felix Niedner. Düsseldorf 1965.

- Königsspiegel (Konungs skuggsjá), Latin Speculum regale , originated in the second half of the 13th century in the vicinity of the Norwegian King Håkon . German: Der Königsspiegel. Konungsskuggsjá. O. Rudolf Meissner. Halle / Saale 1944.

- Ívarr Bárðason: Grønland annáll (13th century). In: Carl Christian Rafn : Grønlands historiske Mindesmærker. 3 volumes 1838–1845. Photographic reprint 1976.

- Gustav Storm: Islandske Annaler indtil 1578 . Christiania 1888. Reprinted Oslo 1977, ISBN 82-7061-192-1 .

- Secondary literature

- Poul Nørlund : Viking settlements in Greenland - their origins and their fate. Curt-Kabitzsch-Verlag, Leipzig 1937.

- The Vikings. Time-Life Books, Amsterdam, ISBN 90-5390-521-9 .

- Maritime History - The Vikings. Time-Life Books, Amsterdam, ISBN 3-86047-033-7 .

- Paul Herrmann: 7 over and 8 blown away - the adventure of early discoveries. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1952, ISBN 3-499-16646-1 .

- Grethe Authén Blom: Grønlandshandel . In: Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder . Copenhagen 1960, vol. 5, col. 519-523.

- CL Vebæk: colonization af Grønland . In: Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder . Copenhagen 1963, Gd. 8, Sp. 650-658.

- Knud J. Krogh: Erik den Rødes Grønland. National Museum, Copenhagen 1967.

- Bertil Almgren et al. a .: The Vikings - history, culture and discoveries . Heyer, Essen 1968.

- Rudolf Pörtner: The Viking Saga . Droemersche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-426-00337-6 .

- Harald Steinert: A Thousand Years of New World . DVA, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-421-06113-0 .

- SE Albrethsen: Greenland . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Vol. 13, Berlin 1999, pp. 63-71.

- Jette Arneborg: Nordboliv i Greenland . In: Else Roesdahl (Ed.): Dagligliv i Danmarks middelalder . Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2004, ISBN 87-7934-106-3 .

- Niels Lynnerup: Life and Death in Norse Greenland . In: Vikings - the North Atlantic Saga . Washington 2000, ISBN 1-56098-995-5 .

- Kirsten A. Seaver : “Pygmies” of the Far North. In: Journal of World History 19, Issue 1, 2008, pp. 63–87.

- Eli Kintisch: The lost Norse. Archaeologists have a new answer to the mystery of Gereenland's Norse, who thrived for centuries and then vanished . In: Science , Vol. 354, No. 6313 (November 11, 2016), pp. 696-701 ( online ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Saga of the Greenlanders . Cape. 2; Land Book Book 2, Chapter 14.

- ↑ chap. 86 and 96: He then received a missionary order for Greenland from King Olav.

- ↑ It is a significant peculiarity that all later private churches were built very close to the main building of the courtyard, but this, exactly as described in the saga, was built very far away from the main house due to the continuing paganism of Erik the Red.

- ↑ Erich Rackwitz : Stranger Paths - Unknown Seas. Urania-Verlag, Leipzig / Jena / Berlin 1980, pp. 67-70.

- ↑ D. Dahl-Jensen, K. Mosegaard, N. Gundestrup et al .: Past Temperatures Directly from the Greenland Ice Sheet. In: Science 282, No. 5387, 1998, pp. 268-271, doi: 10.1126 / science.282.5387.268

- ↑ Niels Lynnerup: The Greenland Norse: A Biological-Anthropological Study , 1989

- ↑ JPHHansen, Jørgen Meldgaard and Jørgen Nordqvist: Qilakitsoq. The grønlandske mumier from 1400-tallet. 1985.

- ↑ Sheep, goat

- ^ Ingrid Mainland: Pastures lost? A dental microwear study of ovicaprine diet and management in Norse Greenland. In: Journal of Archaeological Science 33, 2006, pp. 238-252.

- ↑ E.g. Paul Herrmann.

- ^ Günther Stockinger: When the Tranfunzeln went out. Bone analyzes show how the Vikings on Greenland adapted to the cooling in the Middle Ages: cattle breeders became seal hunters. Why did they give up their colony? In: Der Spiegel 2, 2013, pp. 104f.

- ↑ Krogh p. 38

- ^ TH McGovern: Bones, Buildings, and Boundaries: Paleoeconomic Approaches to Norse Greenland . In: CD Morris and J. Rackham (Eds.): Norse and Later Settlement and Subsistence in the North Atlantic . Glasgow University Press, 1992, pp. 157-186.

- ^ Paul Nørlund: Viking settlements in Greenland. Their creation and their fate. Ernst Käbitzsch Leipzig 1937, p. 52, fig. 41.

- ↑ Krogh p. 71.

- ↑ Krogh p. 52.

- ↑ Heike Braukmüller: Greenland - yesterday and today. Greenland's path of decolonization . Weener, Ems 1990, ISBN 3-88761-043-1 , p. 201 .