Zabern affair

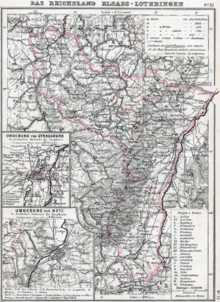

The Zabern affair (French Affaire de Saverne or Incident de Saverne ) was a domestic political crisis that occurred in the German Empire at the end of 1913 . The occasion was protests in the Alsatian Zabern (French Saverne ), the location of two battalions of the Prussian Infantry Regiment 99 , after a lieutenant had insulted the Alsatian population. The military responded to the protests with arbitrary acts that were not legally covered . These attacks led to a debate in the Reichstag on the militaristic onesStructures of German society and the position of the Reich leadership in relation to Kaiser Wilhelm II . The affair not only weighed heavily on the relationship between the realm of Alsace-Lorraine and the rest of the German Empire, it also led to the first vote of disapproval in German history against an Imperial Chancellor and to a considerable loss of reputation for the emperor and the military.

Occasion and course of the Zabern affair

Lieutenant Forstner insults the Alsatians

The 20-year-old lieutenant Günter Freiherr von Forstner (born April 15, 1893 - died August 29, 1915 in Kobryn ) had made derogatory comments about the inhabitants during a recruitment in Zabern on October 28, 1913 and urged his subordinates to to use the side gun in case of doubt in case of conflict . He said at the parade ground in front of the assembled troops: ". If you are attacked, you make use of your weapon usage" to a known because of a stabbing convicted recruits turned, he continued: "And if you doing so a Wackes pierce through the pile so it doesn't do any harm. You will then receive a reward of ten marks from me. ” Sergeant Willy Höflich, who was present at the briefing, then stated that he would give“ another three marks ”. Alsatian soldiers were among the inmates. “Wackes” was a dirty word for Alsatians and meant “rascal”, “loiter” or “good-for-nothing”. In the opinion of contemporaries it had the meaning "like the ' Saupreuss ' in the mouth of the South German". Nine days later, on November 6, 1913, the Zaberner Anzeiger reported on the incident that witnesses had reported to an editor.

On another occasion the lieutenant is said to have asked an Alsatian soldier to report to him with the words “I am a wackes”. In addition, von Forstner had often warned his men in aggressive language about French foreign agents who wanted to poach them for the Foreign Legion . In this context he is said to have said, among other things: " You can shit on the French flag !" These statements by Forstners only reached the public in mid-November through further press reports and caused renewed excitement, with the French press now also promoting the process interested.

Public indignation and the unyielding military

The appearance of the report about this incident in the two local newspapers Elsässer and Zaberner Anzeiger led to resentment among the local population and protests against the treatment by the military broke out in the following days. According to the Alsatians, the military behaved like occupiers of a foreign power. The Alsace-Lorraine governor Karl von Wedel , a general and diplomat, suggested that the regimental commander Friedrich Ernst von Reuter and the commanding general Berthold von Deimling should transfer the lieutenant as a disciplinary measure. Reuter and Deimling disregarded this advice. In their view, a serious punishment of the lieutenant was incompatible with the honor and reputation of the army, because it would have meant admitting an officer's mistake. The emperor, as superior of the governor, and the crown prince also mingled in the affair in this sense. Thereupon Lieutenant von Forstner was sentenced to only six days of room arrest. The official statement by the Strasbourg authorities on November 11 downplayed the incident, claiming that " Wackes " was a generic term for contentious people. Eleven days later, ten members of the fifth company of the 99th Infantry Regiment were arrested and charged with reporting confidential information about the Zabern affair to the press.

The protests in the Alsatian public continued unimpressed. The mood deteriorated further because Lieutenant von Forstner appeared in public again after his house arrest and was always accompanied by an escort of four armed soldiers on the instructions of the garrison command , which was particularly important for everyday activities such as shopping for chocolate and cigarettes seemed like a provocation. The young lieutenant was only able to move through the city under the mockery of the locals. During his appearances outside the barracks, von Forstner was repeatedly mocked and abused, especially by young demonstrators, without the local police authorities being able to prevent this. Colonel Ernst von Reuter thereupon, on instructions from General von Deimling, asked the chairman of the local civil administration, District Director Georg Mahl , to restore order with the help of the police, otherwise he would have to take measures himself and have the state of siege explained. Mahl, who, as an Alsatian, sympathized with the population, rejected the demand that the protesters had behaved peacefully and had not violated the law, and responded to Reuter's threat to declare the state of siege that this was unconstitutional, since only the emperor could declare the state of siege .

The situation escalates

On November 28, 1913, a large crowd gathered again on the square in front of the Prussian military barracks, which this time led to an inappropriate backlash by the troops: Von Reuter instructed Lieutenant Schadt, who was the officer on watch at the time, to move the crowd dissolve. He called the guards to arms and three times called on the demonstrating citizens to part and end their gathering. The soldiers then drove the crowd across the square into a side street under threat of armed violence and arrested a large number of people without legal basis. Among the prisoners were the president, two judges and a public prosecutor from the Zabern regional court , who happened to get into the crowd when leaving the courthouse. 26 of the arrested people (including the two district judges, Kalisch and Boemelmanns) were held overnight in the castle's cellar, the so-called Pandurenkeller . In addition, soldiers illegally searched the editorial offices of a local newspaper for evidence of informants who had brought Forstner's mistakes to the public.

A state of siege was imposed on the city , so that the military effectively took over the government and suspended the civil administration. To prevent further demonstrations and harassment, soldiers with bayonets were allowed to patrol the streets and set up machine guns .

The first reactions of the emperor

At the time, Kaiser Wilhelm II was hunting on the estate of Max Egon Fürst zu Fürstenberg in Donaueschingen . Although this trip had been organized long before the events in Zabern, Wilhelm's lack of interest left a bad impression. According to rumors, Empress Auguste Viktoria had even requested a train to go to her husband's house and to get him to return to Berlin . According to the historian Wolfgang J. Mommsen , Wilhelm II underestimated the political dimension of the events in Alsace at this time. The reports that the Alsace-Lorraine governor Karl von Wedel sent to Donaueschingen, in which he described the incidents as excessive and illegal and asked for personal consultation with the emperor, received hesitant answers. Wilhelm II wanted to wait for the report from the military headquarters in Strasbourg beforehand.

On November 30, the Prussian Minister of War Erich von Falkenhayn , the responsible commanding general in Strasbourg, Berthold von Deimling, and several other high-ranking officers arrived in Donaueschingen, and a six-day consultation began. The public was additionally upset because the emperor apparently only wanted to hear the military's point of view. Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , who was passed over and came under increasing pressure, joined the conference shortly before its end. From the point of view of critical sections of the population, the result was sobering; the emperor approved of the behavior of the military officers and saw no evidence that they had exceeded their authority. Deimling sent a general to Zabern who resumed civil authority on December 1st.

Forstner's second misstep

On December 2nd, von Forstner, who had meanwhile been transferred to another company, led a group of soldiers to Dettweiler as part of a military exercise in the vicinity of Zabern . He was recognized by workers near a shoe factory and greeted with mocking shouts. The lieutenant then lost his temper and gave the order to arrest the passers-by, who were able to escape except for a physically handicapped journeyman cobbler. In his anger, v. Forstner knocked down the already arrested young man with his saber, so that he suffered severe head injuries. This renewed act of aggression escalated the affair.

Forstner was disciplined because of this incident and sentenced by a military court in the first instance to 43 days of arrest, but the second instance overturned the sentence. Although five armed soldiers had accompanied him and the shoemaker was unarmed and paralyzed on one side, the judges interpreted his actions as self-defense , since the shoemaker had been guilty of insulting majesty . In military circles, Forstner received encouragement because he had "defended the honor of the army" with his act of violence. He was transferred to the 3rd Pomeranian Infantry Regiment No. 14 in Bromberg and fell on August 29, 1915 near Kobrin , Russia.

Protests throughout the German Reich

As early as November 28, the Zabern town council sent a telegram to Kaiser Wilhelm II, Bethmann Hollweg and Falkenhayn and protested against the arbitrary arrests of his citizens. Two days later, a 3000-strong SPD meeting took place in Mulhouse , demonstrating against the attacks by the soldiers. In a resolution, the participants described the state as a military dictatorship and called on people to oppose the prevailing situation by means of strikes if necessary . In Strasbourg, on December 2, the mayors of several cities in Alsace-Lorraine called on the emperor to take measures to ensure the protection of their residents from arbitrary military behavior.

The wave of outrage spread across the entire Reich, especially in the SPD environment, there was horror at the military's approach. On December 3, the party executive of the SPD called all organizations of the party to protest meetings. Four days later, in seventeen German cities, u. a. In Berlin , Breslau , Chemnitz , Duisburg , Düsseldorf , Elberfeld (now part of Wuppertal ), Cologne , Leipzig , Mülheim an der Ruhr , Munich , Solingen and Strasbourg , rallies took place at which Social Democrats demonstrated against the arbitrary rule of the military and Bethmann Hollweg and Falkenhayn called for resignation. The events in Zabern sparked a popular movement against militarism and for the defense of the rights of national minorities in the German Reich.

However, there was no sign of the government or the emperor giving in. In order to avoid further problems for the time being, the emperor ordered a temporary relocation of the Zabern units from Donaueschingen on December 5th . In the next two days the soldiers moved to the military training areas in Oberhofen (near Hagenau ) and Bitsch .

Further uprisings were suppressed. The court martial in Strasbourg sentenced two recruits from Zabern to three and six weeks of military arrest on December 11, respectively, for publicly confirming Forstner's insulting statements. The Strasbourg police confiscated at the request of the local command of the XV. Army Corps under General von Deimling on December 17, one of the Gramophone Company produced Cromer and Schrack record . This revealed the events in the context of the Zabern affair in dialogues, which were accompanied by drum rolls. The military also filed a criminal complaint for insulting German officers. Accordingly, the protests flagged.

Disapproval vote against Bethmann Hollweg

The events in Zabern also sparked heated debates in the Reichstag . The Center , the SPD and the Progressive People's Party put parliamentary questions to the Chancellor. Three MPs - Karl Hauss from the Center, Adolf Röser from the Progressive Party and Jacques Peirotes from the Social Democrats - opened the discussion on December 3 by presenting their critical views of the Zabern affair on behalf of their party. Bethmann Hollweg played down the behavior of the military in his subsequent speech. According to observers of the debate, he looked visibly nervous and battered. After him, Falkenhayn made his first statement before the Reichstag. He defended the officers who had only done their duty and, among other things, sharply attacked the press, which had used propagandistic methods to play up the affair in order to influence the military.

At this point it became clear how different the views of the Reichstag and the Reich Chancellor were. The debate continued the next day, with Bethmann Hollweg again commenting on the events. Although his second speech made a better impression, it could no longer turn the mood in the Reichstag. On December 4th, for the first time in the history of the empire, parliament made use of the possibility of a disapproval vote (section 33a of the Reichstag's rules of procedure), which it had been entitled to since 1912. With 293 votes in favor with 4 abstentions and 54 votes against, which came exclusively from the ranks of the conservatives , it disapproved of the government's behavior “not in accordance with the view of the Reichstag”.

As expected, the Chancellor rejected the resignation now demanded by the SPD.

consequences

The trial against von Reuter and Schadt

The court hearing that took place before the court martial in Strasbourg from January 5 to 10, 1914, acquitted the two main responsible, Colonel von Reuter and Lieutenant Schadt, of the accusation of unlawfully appropriating civil police violence. The court apologized for the attacks by the soldiers, but blamed the civil authorities, whose job it would have been to keep order. It referred to a previously forgotten Prussian cabinet order from 1820, for which it was also doubtful whether the legality also extended to the Reichsland . According to the order , if the civil administration neglects to protect order, the highest-ranking military official in a city must take legal power. Because the defendants acted under these provisions, they could not be convicted.

While many liberal citizens, who had followed the trial with interest, were now disappointed, there was great jubilation among the military officials present at the verdict; while they were still in the courtroom, they congratulated the accused. Wilhelm II was also visibly pleased and even awarded a medal from Reuter by return of post. However, the military by no means left the stage as a strong and self-confident victor, as it had become clear how strongly the public even followed and disapproved of a verbal utterance by a soldier.

Legal regulation of military operations inside

On January 14th, the Reichstag decided to set up a committee to regulate the rights of the military in relation to civil authority. Two motions by NLP chairman Ernst Bassermann and center politician Martin Spahn , which requested the Reich government to clarify the civil law competence of military authorities, were approved by a majority ten days later by the Reichstag.

The result, the "regulation on the use of arms by the military and its participation in the suppression of internal unrest," was issued by the emperor on March 19. It prohibited the Prussian army from arbitrarily interfering with the competence of civil authorities. Instead, a troop deployment must be requested beforehand by civil authorities. The law lasted until January 17, 1936, when the National Socialists repealed it by means of the "Ordinance on the Use of Arms by the Wehrmacht ".

Resurgence of the Reichstag debate

The criminal law scholar Franz von Liszt sparked a new debate in the Reichstag when he denied the validity of the cabinet order from 1820. On January 23, however, Bethmann Hollweg confirmed the validity of the order in the Reichstag and thereby legitimized the military actions in Zabern.

Publicity

The affair made it clear how strong the civil society public had become in the German Reich, what major role parliament played in public, how controversial militaristic tendencies were - and how little the Kaiser could isolate himself from this public. The fact that a soldier insulted a civilian could throw the whole empire into a crisis - without resulting in deaths. The new law introduced by the Reichstag, which severely restricted the use of weapons by the military at home, confirmed the liberal bourgeoisie, which had protested against militarism.

Consequences for Alsace-Lorraine

The relationship between Alsace-Lorraine and the rest of the German Empire was noticeably affected. Alsatians and Lothringers felt more than ever exposed to the arbitrariness of the German military. The second chamber of the Alsace-Lorraine parliament issued a resolution on January 14th on the incidents. While defending the conduct of the civil authorities, she condemned the action of the military and the acquittal of Reuter's regimental commander. Members of the state parliament from various parties founded the League for the Defense of Alsace-Lorraine in Strasbourg on February 26th .

The Zabern affair also led to personnel changes, as a result of which the two most important civilian positions in Alsace-Lorraine were filled. On January 31, the State Secretary of the Ministry for Alsace-Lorraine , Hugo Freiherr Zorn von Bulach , was replaced by the Potsdam Higher President Siegfried Graf von Roedern . Governor Karl von Wedel took his hat on April 18, whereupon the Emperor, to the disappointment of the Alsatians, brought the Prussian Interior Minister Johann von Dallwitz into this office. Dallwitz was a staunch advocate of the state and also rejected the constitution that had been granted to the Reichsland in 1911.

Processing in literature and language

The writer Heinrich Mann dealt with the Zabern affair in his novel Der Untertan .

The writer Ulrich Rauscher mocked in a poem about the "good citizen":

Whether your kind are in heap in

front of bayonets and saber blows -

march, march! Hurry up! -

Running the gauntlet: you are all love of lieutenants!

You only feel

truly comfortable in the fatherland when you push your pistons .

Damn who bare

themselves like that after emasculating themselves!

Furthermore, in the grace of

the saber will be cut over your brain!

You are castrati of the German Reich!

Hurray, you iron bride!

Kurt Tucholsky made fun of Lieutenant Forstner's "courage" in a poem for Vorwärts :

The hero of Zabern

A “man” with a long knife,

and twenty years -

a hero, a hero and chocolate eater,

and not a single whisker.

It stalks in Zabern's long streets

and crows soprano -

will the child be left without supervision for a long time? -

It is the very highest railway! -

> This is one of the many we need! -

He's leading the corps!

And deeply moved you can see his people diving

deep into every drain pipe after enemies.

Because after all, you make your prey -

who dares wins!

Today it is a lame cobbler

and tomorrow it is an orphan.

In short: he has courage, cow ash or better:

a whole man! -

Because if someone defends himself, he stabs the knife straight

away, because the other person cannot defend himself.

The Simplicissimus dedicated a leaflet to the affair .

Based on the behavior of the military, the term zabernism found its way into the English language as a term for the abuse of military force or for tyrannical, aggressive behavior in general .

Contemporary quotes

"The whole of Zabern's history is explosive - a sign of how great the French agitation under the noses of our civil authorities has rummaged and worked undetected and unhindered until this result was achieved in a once German city."

“Just as no one has supposedly - to speak to Bismarck - imitated the Prussian lieutenant, so in fact no one has yet been able to imitate the Prussian-German militarism completely, which is not only a state within a state, but actually a state above Has become a state [...] "

"Do we live in a South American republic where every colonel is allowed to dictate the law to the judicial authorities, and do the life and freedom of the citizens depend on the decisions of a casino company?"

"We have to protect ourselves against the fact that academic and military mouth heroism becomes the voice of German convictions."

"Sputtering is just a symptom."

"Always firm druff!"

"Saber rule"

"And isn't killing and mutilation in war the real profession and the true nature of those 'military authorities' whose offended authority has shown its teeth in Zabern?"

"There are 'incidents' in politics through which the essence of a certain order somehow suddenly, for a relatively minor cause, comes to light with unusual force and clarity."

literature

- Frank Bösch : Limits of the "Authoritative State". Media, politics and scandals in the empire, in: Sven Oliver Müller / Cornelius Torp (eds.), The German Empire in the Controversy (Fs. For Hans-Ulrich Wehler on the 75th), Göttingen 2008, pp. 136–152.

- Erwin Schenk: The case of Zabern (= contributions to the history of the post-Bismarckian period and the world war). W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1927.

- Hans-Günter Zmarzlik: Bethmann Hollweg as Reich Chancellor 1909–1914. Studies on the possibilities and limits of its domestic political power position (= contributions to the history of parliamentarism and political parties. Vol. 11). Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1957, pp. 114–130.

- The Zabern tragedy (1913). In: Paul Schweder: The Great Criminal Trials of the Century. A German pitaval . Kriminalistik Verlag, Hamburg 1961, p. 192 ff.

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler : The Zabern case. Review of a constitutional crisis in the Wilhelmine Empire. In: The world as history. 23, 1963, pp. 27-46; again as: Symbol of the semi-absolutist system of rule - The Zabern case of 1913/14. In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Hotspots of the Empire 1871-1918. Studies on German social and constitutional history. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1970, pp. 65-83; again as: The Zabern case of 1913/14 as a constitutional crisis of the Wilhelmine Empire. In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Hotspots of the Empire 1871-1918. 2nd edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1979, pp. 70-88 and 449-458.

- David Schoenbaum : Zabern 1913. Consensus Politics in Imperial Germany. George Allen & Unwin, London 1982, ISBN 0-04-943025-4 .

- Rainer Nitsche (Ed.): Diarrhea in Zabern. A military dismantling. Transit Buchverlag, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-88747-010-9 .

- Richard W. Mackey: The Zabern Affair, 1913-1914. University Press of America, Lanham 1991, ISBN 0-8191-8408-X .

- Gerd Fesser : "… lucky if blood is flowing now!" . Timelines. In: The time . No. 46/1993, p. 88.

- Christopher Fischer: Alsace to the Alsatians. Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1871-1939. Berghahn, New York 2010, ISBN 978-1-78238-394-9 .

- Wolfgang J. Mommsen : Was the emperor to blame for everything? Wilhelm II and the Prussian-German power elites . Ullstein, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-548-36765-8 , pp. 203-209.

- Kirsten Zirkel: From militarist to pacifist. General Berthold von Deimling - a political biography . Dissertation . Klartext, Essen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89861-898-4 . Dissertation University of Düsseldorf 2006 (PDF; 3.1 MB); Chapter IV.2 “The Zabern Affair”, p. 123 ff.

Web links

- Volker Ullrich: Taking action in Alsace. In: The time . October 24, 2013, accessed January 8, 2014.

- Bärbel Nückles: The Zabern affair opened a wound in Alsace. In: Badische Zeitung. November 13, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Gerd Fesser: "... good luck if blood is flowing now!" In: Die Zeit. No. 46/1993, p. 88.

- ↑ The contemporary witness Höflich, around 1930 city secretary in Guben (see Guben 1930 address book ), published a memory book about the Zaber affair in 1931 ( Affaire Zabern: Communicated by one of the two "wrongdoers". Verlag für Kulturpolitik, Berlin 1931), in which he published the Describes the events and backgrounds of the affair from his point of view.

- ↑ Erwin Schenk: The Zabern case. Stuttgart 1927, p. 8.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Anschütz: Zabern. In: Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung. Volume 18 (1913), p. 1457.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: When the throne wavered. The end of the Hohenzollern Empire 1890–1918. Bremen 1993, p. 69.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: The Zabern case of 1913/14 as a constitutional crisis of the Wilhelmine Empire. Göttingen 1979, p. 72.

- ^ So Volker Ullrich: Reaching through in Alsace . In: The time . October 24, 2013.

- ↑ a b Colonel Ernst von Reuter was a brother of the naval officer Ludwig von Reuter , who, as rear admiral, gave the order for the German deep-sea fleet to self-sink at Scapa Flow on June 21, 1919 .

- ^ Karl-Heinz Deisenroth in a letter to the editor entitled Friedrich Ernst von Reuter in Zabern in the FAZ on December 31, 2013.

- ^ Albert Hopmann: The eventful life of a 'Wilhelminer'. Diaries, letters, and notes 1901–1920. Edited by Michael Epkenhans (series of publications by the Military History Research Office ), Oldenbourg , Munich 2004, p. 344 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang J. Mommsen: Was the emperor to blame for everything? P. 203.

- ↑ Reclams Universum - Modern Illustrated Weekly. Volume 30, No. 11, p. 578 , published on December 11, 1913.

- ↑ Patric Seibel: Saber-rattling ignorance of the imperial military. In: deutschlandfunk.de. October 28, 2013, accessed July 21, 2015 .

- ^ German Society for Heereskunde (Hrsg.): Journal for Heereskunde . tape 68 , issues 411-414, 2004, pp. 422 .

- ↑ Minutes of the 181st session in the 13th legislative period, Stenographic Reports, pp. 6139–6171.

- ^ Minutes of the 182nd session in the 13th legislative period, Stenographic Reports, pp. 6173–6200.

- ↑ Frank Bösch : Limits of the "Authoritative State". Media, politics and scandals in the Empire, in: Sven Oliver Müller / Cornelius Torp (eds.), The German Empire in the Controversy (Fs. For Hans-Ulrich Wehler on the 75th), Göttingen 2008, pp. 136–152, here Pp. 147-149.

- ^ Ulrich Rauscher: The good citizens. In: The Schaubühne . January 15, 1914, p. 70.

- ^ Theobald Tiger (Kurt Tucholsky): The hero of Zabern. In: Forward . Vol. 30, No. 318, December 3, 1913.

- ^ Leaflet of the Simplicissimus. (PDF; 1.6 MB, accessed April 8, 2013).

- ↑ Quoted from Volker Ullrich: Reaching through in Alsace . In: The time . October 24, 2013 ( dash to structure the sentence for the purpose of better understandability by the editor ).

- ↑ Karl Liebknecht in a lecture to the Mannheim Youth Congress in October 1906, then again in his work Militarism and Antimilitarism with special consideration of the international youth movement . Leipzig, 1907. Quoted here from Volker R. Berghahn (Hrsg.): Militarismus . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1975, p. 91.

- ↑ Quoted here from Volker Ullrich: Five shots on Bismarck: historical reports 1789–1945 . Beck, Munich 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Theodor Heuss: The German Chauvinism. In: March . 7. Vol. 34 of August 23, 1913, p. 269.

- ↑ Theodor Heuss: The Zaberner bowl. In: March . 8th year / no. 3 of January 17, 1914, p. 99.

- ^ Gerhard Anschütz: Zabern. In: Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung. Year 18 (1913), dlib-zs.mpier.mpg.de Sp. 1457 ff. (Based on a headline in the Berliner Tageblatt ; cf. Volker Ullrich: Five shots on Bismarck: historical reports 1789–1945. Munich 2002, p . 67.)

- ^ Rosa Luxemburg: Social Democratic Correspondence. No. 3. Berlin, January 6, 1914.

- ↑ Quotation from Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Hot spots of the Kaiserreich 1871-1918. Göttingen 1979, p. 71.