Lightning: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Altered bibcode. Added issue. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 551/3180 |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Weather phenomenon involving electrostatic discharge}} |

|||

: ''For alternate meanings, see [[Lightning (disambiguation)]].'' |

|||

{{Hatnote group| |

|||

'''Lightning''' is a powerful natural [[electrostatic discharge]] produced during a [[thunderstorm]]. This abrupt electric discharge is accompanied by the emission of visible [[light]] and other forms of [[electromagnetic radiation]]. The [[electric current]] passing through the discharge channels rapidly heats and expands the air into [[Plasma (physics)|plasma]], producing acoustic shock waves ([[thunder]]) in the atmosphere. |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|lighting|thunder}}}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=April 2014}} |

|||

[[File:Port and lighthouse overnight storm with lightning in Port-la-Nouvelle.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|Strokes of cloud-to-ground lightning strike the [[Mediterranean Sea]] off of [[Port-la-Nouvelle]] in southern [[France]].]] |

|||

{{Weather}} |

|||

'''Lightning''' is a [[natural phenomenon]] formed by [[electrostatic discharge]]s through the [[atmosphere]] between two [[electrically charged]] regions, either both in the atmosphere or one in the atmosphere and one on the [[land|ground]], temporarily neutralizing these in a near-instantaneous release of an average of between 200 [[megajoule]]s and 7 gigajoules of [[energy]], depending on the type.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Maggio |first1=Christopher R. |last2=Marshall |first2=Thomas C. |last3=Stolzenburg |first3=Maribeth |date=2009 |title=Estimations of charge transferred and energy released by lightning flashes in short bursts |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres |volume=114 |issue=D14 |pages=D14203 |doi=10.1029/2008JD011506 |bibcode=2009JGRD..11414203M|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="SEVERE WEATHER 101: Lightning Basics">{{cite web |url=https://www.nssl.noaa.gov/education/svrwx101/lightning/ |title=SEVERE WEATHER 101 - Lightning Basics |website=nssl.noaa.gov |access-date=October 23, 2019}}</ref><ref name="FJFK: Lightning Facts">{{cite web |url=https://www.factsjustforkids.com/weather-facts/lightning-facts-for-kids.html |title=Lightning Facts |website=factsjustforkids.com |access-date=October 23, 2019}}</ref> This discharge may produce a wide range of [[electromagnetic radiation]], from heat created by the rapid movement of [[electron]]s, to brilliant flashes of [[visible light]] in the form of [[black-body radiation]]. Lightning causes [[thunder]], a sound from the [[shock wave]] which develops as gases in the vicinity of the discharge experience a sudden increase in pressure. Lightning occurs commonly during [[thunderstorm]]s as well as other types of energetic [[weather]] systems, but [[volcanic lightning]] can also occur during [[volcanic eruption]]s. Lightning is an [[atmospheric electrical]] phenomenon and contributes to the [[global atmospheric electrical circuit]]. |

|||

[[Image:Lightning in Arlington.jpg|thumb|right|258px|Lightning over [[Pentagon City, Virginia|Pentagon City]] in [[Arlington County, Virginia]]]] |

|||

== Early lightning research == |

|||

[[Image:Lightning02.jpg|250px|thumb|right|258px|Cloud to cloud lightning]] |

|||

The three main kinds of lightning are distinguished by where they occur: either inside a single [[Cumulonimbus cloud|thundercloud]] (intra-cloud), between two [[cloud]]s (cloud-to-cloud), or between a cloud and the ground (cloud-to-ground), in which case it is referred to as a [[lightning strike]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.weather.gov/media/pah/WeatherEducation/lightningsafety.pdf |title=Severe Weather Safety Guide |publisher=National Weather Service |date=2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.fastfactsforkids.com/weather-facts/lightning-facts-for-kids |title=Lightning Facts |publisher=Fast Facts for Kids |date=2022}}</ref> Many other observational variants are recognized, including "[[heat lightning]]", which can be seen from a great distance but not heard; [[dry lightning]], which can cause [[forest fires]]; and [[ball lightning]], which is rarely observed scientifically. |

|||

During early investigations into electricity via [[Leyden jar]]s and other instruments, a number of people (Dr. Wall, Dr. John Gray, and [[Abbé Nollet]]) proposed that small-scale sparks shared some similarity with lightning. |

|||

Humans have [[Lightning in religion|deified lightning]] for millennia. [[Idiomatic]] expressions derived from lightning, such as the English expression "bolt from the blue", are common across languages. At all times people have been fascinated by the sight and difference of lightning. The fear of lightning is called ''[[astraphobia]]''. |

|||

[[Benjamin Franklin]], who also invented the [[lightning rod]], endeavoured to test this theory using a spire which was being erected in [[Philadelphia]]. Whilst he was waiting for the spire completion, some others ([[Thomas Francois D'Alibard]] and [[De Lors]]) conducted at Marly in [[France]] what became known as the Philadelphia experiments that Franklin had suggested in his book. |

|||

The first known photograph of lightning is from 1847, by [[Thomas Martin Easterly]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://hyperallergic.com/301157/the-first-photographs-of-lightning-crackle-with-electric-chaos/ |title=The First Photographs of Lightning Crackle with Electric Chaos |date=2016-05-25 |website=Hyperallergic |access-date=2019-05-12}}</ref> The first surviving photograph is from 1882, by [[William Nicholson Jennings]],<ref>{{Cite web |title=These are the World's First Photos of Lightning |url=https://petapixel.com/2020/08/05/these-are-the-worlds-first-photos-of-lightning/|date=2020-08-05|website=PetaPixel}}</ref> a photographer who spent half his life capturing pictures of lightning and proving its diversity. |

|||

Franklin usually gets the credit, as he was the first to suggest this experiment. The Franklin experiment is as follows: |

|||

There is growing evidence that lightning activity is increased by [[particulate]] emissions (a form of air pollution).<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.science.org/content/article/air-pollution-helps-wildfires-create-their-own-lightning|title= Air pollution helps wildfires create their own lightning}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://physicsworld.com/a/pollution-boosts-risk-of-lightning/|title= Pollution boosts risk of lightning|date= February 13, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-bolt-from-the-brown-why-pollution-may-increase-lightning-strikes/|title=A Bolt from the Brown: Why Pollution May Increase Lightning Strikes|website=[[Scientific American]] }}</ref> However, lightning may also improve air quality and clean greenhouse gases such as methane from the atmosphere, while creating [[nitrogen oxide]] and [[ozone]] at the same time.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.arl.noaa.gov/news-pubs/arl-news-stories/lightning-produces-molecules-that-clean-greenhouse-gases-from-the-atmosphere/|title=Lightning Produces Molecules that Clean Greenhouse Gases from the Atmosphere}}</ref> Lightning is also the major cause of wildfire,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/safety/wildfire-status/wildfire-response/what-causes-wildfire|title=What causes wildfire}}</ref> and wildfire can contribute to climate change as well.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-wildfires |title=Climate Change Indicators: Wildfires, US EPA |date=July 2016 |accessdate=2023-07-06}}</ref> More studies are warranted to clarify their relationship. |

|||

''Whilst waiting for completion of the spire, he got the idea of using a flying object, such as a [[kite flying|kite]], instead. During the next [[thunderstorm]], which was in June 1752, he raised a kite, accompanied by his son as an assistant. On his end of the string he attached a key and tied it to a post with a [[silk]] thread. As time passed, Franklin noticed the loose fibers on the string stretching out; he then brought his hand close to the key and a spark jumped the gap. The rain which had fallen during the storm had soaked the line and made it conductive.'' |

|||

== Electrification == |

|||

However, in his autobiography (written 1771-1788, first published 1790), Franklin clearly states that he performed this experiment after those in France, which occurred weeks before his own experiment, without his prior knowledge as of 1752. |

|||

[[File: Understanding Lightning - Figure 1 - Cloud Charging Area.gif|thumb|(Figure 1) The main charging area in a thunderstorm occurs in the central part of the storm where the air is moving upward rapidly (updraft) and temperatures range from {{convert|-15|to|-25|C|F}}.]] |

|||

[[File:Graupel animation 3a.gif|thumb|(Figure 2) When the rising ice crystals collide with graupel, the ice crystals become positively charged and the graupel becomes negatively charged.]] |

|||

[[File:Charged cloud animation 4a.gif|thumb|The upper part of the thunderstorm cloud becomes positively charged while the middle to the lower part of the thunderstorm cloud becomes negatively charged.]] |

|||

The details of the charging process are still being studied by scientists, but there is general agreement on some of the basic concepts of thunderstorm electrification. Electrification can be by the [[triboelectric effect]] leading to electron or ion transfer between colliding bodies. Uncharged, colliding water-drops can become charged because of charge transfer between them (as aqueous ions) in an electric field as would exist in a thunder cloud.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Jennings | first1=S. G. | last2=Latham | first2=J. | title=The charging of water drops falling and colliding in an electric field | journal=Archiv für Meteorologie, Geophysik und Bioklimatologie, Serie A | publisher=Springer Science and Business Media LLC | volume=21 | issue=2–3 | year=1972 | doi=10.1007/bf02247978 | pages=299–306| bibcode=1972AMGBA..21..299J | s2cid=118661076 }}</ref> The main charging area in a thunderstorm occurs in the central part of the storm where air is moving upward rapidly (updraft) and temperatures range from {{convert|-15|to|-25|C|F}}; see Figure 1. In that area, the combination of temperature and rapid upward air movement produces a mixture of super-cooled cloud droplets (small water droplets below freezing), small ice crystals, and [[graupel]] (soft hail). The updraft carries the [[Supercooling|super-cooled]] cloud droplets and very small ice crystals upward. |

|||

At the same time, the graupel, which is considerably larger and denser, tends to fall or be suspended in the rising air.<ref name="NOAA">{{cite web|url=http://www.lightningsafety.noaa.gov/science/science_electrication.htm |title=NWS Lightning Safety: Understanding Lightning: Thunderstorm Electrification |publisher=[[National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]]|access-date=25 November 2016|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161130080723/http://www.lightningsafety.noaa.gov/science/science_electrication.htm |archive-date=November 30, 2016|df=mdy-all}} {{PD-notice}}</ref> |

|||

As news of the experiment and its particulars spread, the experiment was met with attempts at replication. However, experiments involving lightning are always risky and frequently fatal. The most well-known death during the spate of Franklin imitators was that of Professor [[Georg Richmann]], of [[Saint Petersburg, Russia]]. He had created a set-up similar to Franklin's, and was attending a meeting of the Academy of Sciences when he heard [[thunder]]. He ran home with his engraver to capture the event for posterity. While the experiment was underway, [[ball lightning]] appeared, collided with Richmann's head, and killed him, leaving a red spot. His shoes were blown open, parts of his clothes singed, the engraver knocked out, the doorframe of the room split, and the door itself torn off its hinges. |

|||

The differences in the movement of the precipitation cause collisions to occur. When the rising ice crystals collide with graupel, the ice crystals become positively charged and the graupel becomes negatively charged; see Figure 2. The updraft carries the positively charged ice crystals upward toward the top of the storm cloud. The larger and denser graupel is either suspended in the middle of the thunderstorm cloud or falls toward the lower part of the storm.<ref name="NOAA"/> |

|||

== Modern research == |

|||

[[Image:Lightning simulator questacon05.jpg|thumb|250px|A [[Tesla coil]] creating small "leaders" at Questacon, Canberra]] |

|||

The result is that the upper part of the thunderstorm cloud becomes positively charged while the middle to lower part of the thunderstorm cloud becomes negatively charged.<ref name="NOAA"/> |

|||

Although experiments from the time of Franklin showed that lightning was a discharge of static electricity, there was little improvement in theoretical understanding of lightning (in particular how it was generated) for more than 150 years. The impetus for new research was from the field of [[power engineering]]: [[Electric power transmission|power transmission lines]] came into use, and engineers needed to know much more about lightning. Although ''causes'' were debated (and are today to some extent), research produced a wealth of new information about lightning phenomena, especially amounts of current and energy involved. |

|||

The following picture emerged: |

|||

The upward motions within the storm and winds at higher levels in the atmosphere tend to cause the small ice crystals (and positive charge) in the upper part of the thunderstorm cloud to spread out horizontally some distance from the thunderstorm cloud base. This part of the thunderstorm cloud is called the anvil. While this is the main charging process for the thunderstorm cloud, some of these charges can be redistributed by air movements within the storm (updrafts and downdrafts). In addition, there is a small but important positive charge buildup near the bottom of the thunderstorm cloud due to the precipitation and warmer temperatures.<ref name="NOAA"/> |

|||

An initial discharge, (or path of ionised air), called a "[[step_leader|stepped leader]]", starts from the [[thundercloud]] and proceeds generally downward in a number of quick jumps, typical length 50 meters, but taking a relatively long time (200 milliseconds) to reach the ground. This initial phase involves a small [[electric current]] and is almost invisible compared to the later effects. When the downward leader is quite close, a small discharge comes up from a grounded (usually tall) object because of the intensified electric field. |

|||

The induced separation of charge in pure liquid water has been known since the 1840s as has the electrification of pure liquid water by the triboelectric effect.<ref>Francis, G. W., "Electrostatic Experiments" Oleg D. Jefimenko, Editor, Electret Scientific Company, Star City, 2005</ref> |

|||

Once the ground discharge meets the stepped leader, the circuit is closed, and the main stroke follows with much higher current. The main stroke travels at about 0.1 [[Speed of light|''c'']] (100 million feet per second) and has high current for 100 microseconds or so. It may persist for longer periods with lower current. |

|||

[[William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin|William Thomson]] (Lord Kelvin) demonstrated that charge separation in water occurs in the usual electric fields at the Earth's surface and developed a continuous electric field measuring device using that knowledge.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Aplin |first1=K. L. |last2=Harrison |first2=R. G. |title=Lord Kelvin's atmospheric electricity measurements |journal=History of Geo- and Space Sciences |date=3 September 2013 |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=83–95 |doi=10.5194/hgss-4-83-2013|arxiv=1305.5347 |bibcode=2013HGSS....4...83A |s2cid=9783512 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

In addition, lightning often contains a number of restrikes, separated by a much larger amount of time, 30 milliseconds being a typical value. This rapid restrike effect was probably known in antiquity, and the "[[strobe light]]" effect is often quite noticeable. |

|||

The physical separation of charge into different regions using liquid water was demonstrated by Kelvin with the [[Kelvin water dropper]]. The most likely charge-carrying species were considered to be the aqueous hydrogen ion and the aqueous hydroxide ion.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Desmet |first1=S |last2=Orban |first2=F |last3=Grandjean |first3=F |title=On the Kelvin electrostatic generator |journal=European Journal of Physics |date=1 April 1989 |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=118–122 |doi=10.1088/0143-0807/10/2/008|bibcode=1989EJPh...10..118D |s2cid=121840275 }}</ref> |

|||

Positive lightning does not generally fit the above pattern. |

|||

The electrical charging of solid water ice has also been considered. The charged species were again considered to be the hydrogen ion and the hydroxide ion.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dash |first1=J G |last2=Wettlaufer |first2=J S |title=The surface physics of ice in thunderstorms |journal=Canadian Journal of Physics |date=1 January 2003 |volume=81 |issue=1–2 |pages=201–207 |doi=10.1139/P03-011|bibcode=2003CaJPh..81..201D }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dash |first1=J. G. |last2=Mason |first2=B. L. |last3=Wettlaufer |first3=J. S. |title=Theory of charge and mass transfer in ice-ice collisions |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres |date=16 September 2001 |volume=106 |issue=D17 |pages=20395–20402 |doi=10.1029/2001JD900109|bibcode=2001JGR...10620395D |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

== How it is formed == |

|||

[[Image:Double_Lightning_in_Glyfada-Athens.jpg|left|thumb|300px|Double lightning. An extremely rarely captured phenomenon.]] |

|||

An electron is not stable in liquid water with respect to a hydroxide ion plus dissolved hydrogen for the time scales involved in thunder storms.<ref>Buxton, G. V., Greenstock, C. L., Helman, W. P. and Ross, A. B. "Critical Review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (OH/O in aqueous solution." J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 17, 513–886 (1988).</ref> |

|||

The first process in the generation of lightning is the forcible separation of positive and negative [[charge carrier]]s within a cloud or air. The mechanism by which this happens is still the subject of research, but one widely accepted theory is the polarisation mechanism. This mechanism has two components: the first is that falling droplets of ice and rain become electrically polarised as they fall through the atmosphere's natural electric field, and the second is that colliding ice particles become charged by [[electrostatic induction]]. Once charged, by whatever mechanism, work is performed as the opposite charges are driven apart and energy is stored in the [[electric field]]s between them. The positively charged crystals tend to rise to the top, causing the cloud top to build up a positive charge, and the negatively charged crystals and [[hail]]stones drop to the middle and bottom layers of the cloud, building up a negative charge. Cloud-to-cloud lightning can appear at this point. Cloud-to-ground lightning is less common. [[Cumulonimbus cloud|Cumulonimbus]] clouds that do not produce enough ice crystals usually fail to produce enough charge separation to cause lightning. |

|||

The charge carrier in lightning is mainly electrons in a plasma.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Uman|first=Martin|title=All About Lightning|publisher=Dover|year=1986|isbn=978-0-486-25237-7|location=New York|pages=74}}</ref> The process of going from charge as ions (positive hydrogen ion and negative hydroxide ion) associated with liquid water or solid water to charge as electrons associated with lightning must involve some form of electro-chemistry, that is, the oxidation and/or the reduction of chemical species.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Witzke |first1=Megan |last2=Rumbach |first2=Paul |last3=Go |first3=David B |last4=Sankaran |first4=R Mohan |title=Evidence for the electrolysis of water by atmospheric-pressure plasmas formed at the surface of aqueous solutions |journal=Journal of Physics D |date=7 November 2012 |volume=45 |issue=44 |pages=442001 |doi=10.1088/0022-3727/45/44/442001|bibcode=2012JPhD...45R2001W |s2cid=98547405 }}</ref> As [[hydroxide]] functions as a base and [[carbon dioxide]] is an acidic gas, it is possible that charged water clouds in which the negative charge is in the form of the aqueous hydroxide ion, interact with atmospheric carbon dioxide to form aqueous carbonate ions and aqueous hydrogen carbonate ions. |

|||

When sufficient negatives and positives gather in this way, and when the [[electric field]] becomes sufficiently strong, an [[spark gap|electrical discharge]] occurs within the clouds or between the clouds and the ground, producing the ''bolt''. It has been suggested by experimental evidence that these discharges are triggered by [[cosmic ray]] strikes which ionise atoms, releasing electrons that are accelerated by the electric fields, ionising other air molecules and making the air conductive by a [[runaway breakdown]], then starting a lightning strike. During the strike, successive portions of air become conductive as the electrons and positive ions of air molecules are pulled away from each other and forced to flow in opposite directions (stepped channels called [[Step leader|step leaders]]). The conductive filament grows in length. At the same time, electrical energy stored in the electric field flows radially inward into the conductive filament. |

|||

==General considerations== |

|||

When a charged step leader is near the ground, opposite charges appear on the ground and enhance the electric field. The electric field is higher on trees and tall buildings. If the electric field is strong enough, a discharge can initiate from the ground. This discharge starts as [[positive streamer]] and, if it develops as a positive leader, can eventually connect to the descending discharge from the cloud. |

|||

[[File:LightningCNP.ogg|thumb|Four-second video of a lightning strike at [[Canyonlands National Park]] in [[Utah]], U.S.]] |

|||

The typical cloud-to-ground lightning flash culminates in the formation of an electrically conducting [[plasma (physics)|plasma]] channel through the air in excess of {{convert|5|km|mi|abbr=on}} tall, from within the cloud to the ground's surface. The actual discharge is the final stage of a very complex process.<ref>[[#Uman|Uman (1986)]] p. 81.</ref> At its peak, a typical [[thunderstorm]] produces three or more strikes to the [[Earth]] per minute.<ref>[[#Uman|Uman (1986)]] p. 55.</ref> |

|||

Lightning primarily occurs when warm air is mixed with colder air masses,<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g1foWWN5odwC&q=Lightning+occurs+when+warm+air+is+mixed+with+colder+air+masses&pg=PA90|title=Sprites, Elves and Intense Lightning Discharges|last1=Füllekrug|first1=Martin|last2=Mareev|first2=Eugene A.|last3=Rycroft|first3=Michael J.|date=2006-05-01|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=9781402046285|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171104190958/https://books.google.com/books?id=g1foWWN5odwC&pg=PA90&dq=Lightning+occurs+when+warm+air+is+mixed+with+colder+air+masses&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiV44XT9uXUAhVJ7mMKHb3pBUoQ6AEIMDAC#v=onepage&q=Lightning%20occurs%20when%20warm%20air%20is%20mixed%20with%20colder%20air%20masses&f=false|archive-date=November 4, 2017|df=mdy-all|bibcode=2006seil.book.....F}}</ref> resulting in atmospheric disturbances necessary for polarizing the atmosphere.<ref name="Volland1995">{{cite book | editor = Hans Volland | date = 1995 | title = Handbook of Atmospheric Electrodynamics | publisher = CRC Press | page = 204 | isbn = 978-0-8493-8647-3 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=MNPPh7B3WTIC|author1=Rinnert, K. |chapter=9: Lighting Within Planetary Atmospheres|quote=The requirements for the production of lightning within an atmosphere are the following: (1) a sufficient abundance of appropriate material for electrification, (2) the operation of a microscale electrification process to produce classes of particles with different signs of charge and (3) a mechanism to separate and to accumulate particles according to their charge.}}</ref> |

|||

Lightning can also occur within the ash clouds from [[volcano|volcanic eruptions]]{{ref|usgs_hvo}}<sup>,</sup>{{ref|noaa_galgunggung}}, or can be caused by violent [[forest fire]]s which generate sufficient dust to create a [[static charge]]. |

|||

Lightning can also occur during [[dust storm]]s, [[forest fires]], [[tornado]]es, [[volcano|volcanic eruptions]], and even in the cold of winter, where the lightning is known as [[thundersnow]].<ref>[http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/02/100203-volcanoes-lightning/ New Lightning Type Found Over Volcano?] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100209015048/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/02/100203-volcanoes-lightning/ |date=February 9, 2010 }}. News.nationalgeographic.com (February 2010). Retrieved on June 23, 2012.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/1998/98_06_11.html|title=Bench collapse sparks lightning, roiling clouds|access-date=October 7, 2012|publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]]|date=June 11, 1998|work=Volcano Watch|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120114172155/http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/1998/98_06_11.html|archive-date=January 14, 2012|df=mdy-all}}</ref> [[tropical cyclone|Hurricanes]] typically generate some lightning, mainly in the rainbands as much as {{convert|160|km|mi|abbr=on}} from the center.<ref>Pardo-Rodriguez, Lumari (Summer 2009) [http://nldr.library.ucar.edu/repository/assets/soars/SOARS-000-000-000-193.pdf Lightning Activity in Atlantic Tropical Cyclones: Using the Long-Range Lightning Detection Network (LLDN)] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130309085405/http://nldr.library.ucar.edu/repository/assets/soars/SOARS-000-000-000-193.pdf |date=March 9, 2013 }}. MA Climate and Society, Columbia University Significant Opportunities in Atmospheric Research and Science Program.</ref><ref>[https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2006/09jan_electrichurricanes/ Hurricane Lightning] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170815013425/https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2006/09jan_electrichurricanes/ |date=August 15, 2017 }}, NASA, January 9, 2006.</ref><ref>[http://www.unidata.ucar.edu/committees/polcom/2009spring/statusreports/BusingerS09.pdf The Promise of Long-Range Lightning Detection in Better Understanding, Nowcasting, and Forecasting of Maritime Storms] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130309085405/http://www.unidata.ucar.edu/committees/polcom/2009spring/statusreports/BusingerS09.pdf |date=March 9, 2013 }}. Long Range Lightning Detection Network</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Lightning hits tree - NOAA.jpg|right|thumb|Negative C-G lightning with two visible non-connected streamers]] |

|||

A bolt of lightning usually begins when an invisible negatively charged ''stepped leader'' stroke is sent out from the cloud. As it does so, a positively charged ''streamer'' is usually sent out from the positively charged ground or cloud. When the two leaders meet, the electric current greatly increases. The region of high current propagates back up the positive stepped leader into the cloud. This "return stroke" is the most luminous part of the strike, and is the part that is really visible. Most lightning strikes usually last about a quarter of a second. Sometimes several strokes will travel up and down the same leader strike, causing a flickering effect. This discharge rapidly [[superheating|superheats]] the leader channel, causing the air to expand rapidly and produce a [[shock wave]] heard as thunder. |

|||

== {{anchor|Distribution and frequency}} Distribution, frequency and extent == |

|||

It is possible for streamers to be sent out from several different objects simultaneously, with only one connecting with the leader and forming the discharge path. Photographs have been taken on which non-connected streamers are visible such as that shown on the right. |

|||

{{main|Distribution of lightning}} |

|||

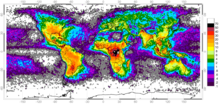

[[File: Global Lightning Frequency.png|thumb|Data obtained from April 1995 to February 2003 from [[NASA]]'s Optical Transient Detector depicting space-based sensors revealing the uneven distribution of worldwide lightning strikes]] |

|||

[[File:Megaflash of 477 miles.png|thumb|A 477-mile megaflash from [[Texas]] to [[Louisiana]], in the United States.<ref name=BAMS>{{citation |title=New WMO Certified Megaflash Lightning Extremes for Flash Distance (768 km) and Duration (17.01 seconds) Recorded from Space |author=Randall Cerveny |collaboration=WMO panel |doi=10.1175/BAMS-D-21-0254.1 |journal=Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society |date=1 February 2022|hdl=2117/369605 |s2cid=246358397 |doi-access=free |hdl-access=free }}</ref>]] |

|||

Lightning is not distributed evenly around [[Earth]]. On Earth, the lightning frequency is approximately 44 (± 5) times per second, or nearly 1.4 [[1,000,000,000 (number)|billion]] flashes per year<ref name="EncyWorldClim freq">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-mwbAsxpRr0C&pg=PA452|title=Encyclopedia of World Climatology|access-date=February 8, 2009|publisher=[[National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]]|author=Oliver, John E.| isbn=978-1-4020-3264-6|date=2005}}</ref> and the median duration is 0.52 seconds<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kákona |first1=Jakub |title=In situ ground-based mobile measurement of lightning events above central Europe |journal=Atmospheric Measurement Techniques|year=2023 |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=547–561 |doi=10.5194/amt-16-547-2023 |bibcode=2023AMT....16..547K |s2cid=253187897 |doi-access=free }}</ref> made up from a number of much shorter flashes (strokes) of around 60 to 70 [[microsecond]]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/lightning2.html|title=Lightning|work=gsu.edu|access-date=December 30, 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115043319/http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/lightning2.html|archive-date=January 15, 2016|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

This type of lightning is known as '''negative lightning''' because of the discharge of negative charge from the cloud, and accounts for over 95% of all lightning. |

|||

Many factors affect the frequency, distribution, strength and physical properties of a typical lightning flash in a particular region of the world. These factors include ground elevation, [[latitude]], [[prevailing wind]] currents, [[relative humidity]], and proximity to warm and cold bodies of water. To a certain degree, the proportions of intra-cloud, cloud-to-cloud, and cloud-to-ground lightning may also vary by [[season]] in [[middle latitudes]]. |

|||

An average bolt of ''negative'' lightning carries a current of 30 [[ampere|kiloamperes]], transfers a charge of 5 [[coulomb]]s, has a potential difference of about 100 [[volt|megavolts]] and dissipates 500 [[joule|megajoules]] (enough to |

|||

light a 100 [[watt]] lightbulb for 2 months). |

|||

Because human beings are terrestrial and most of their possessions are on the Earth where lightning can damage or destroy them, cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning is the most studied and best understood of the three types, even though in-cloud (IC) and cloud-to-cloud (CC) are more common types of lightning. Lightning's relative unpredictability limits a complete explanation of how or why it occurs, even after hundreds of years of scientific investigation. |

|||

Positive lightning makes up less than 5 % of all lightning. It occurs when the ''[[stepped leader]]'' forms at the positively charged cloud tops, with the consequence that a negatively charged ''streamer'' issues from the ground. The overall effect is a discharge of positive charges to the ground. Research carried out after the discovery of positive lightning in the 1970s showed that positive lightning bolts are typically six to ten times more powerful than negative bolts, last around ten times longer, and can strike several kilometers or miles distant from the clouds. During a positive lightning strike, huge quantities of [[extremely low frequency|ELF]] and [[very low frequency|VLF]] [[radio wave]]s are generated. |

|||

About 70% of lightning occurs over land in the [[tropics]]<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5oZUAAAAMAAJ&q=70%25+of+lightning+occurs+in+tropics+on+land|title=Encyclopedia of atmospheric sciences|last1=Holton|first1=James R.|last2=Curry|first2=Judith A.|last3=Pyle|first3=J. A.|date=2003|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=9780122270901|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171104190958/https://books.google.com/books?id=5oZUAAAAMAAJ&q=70%25+of+lightning+occurs+in+tropics+on+land&dq=70%25+of+lightning+occurs+in+tropics+on+land&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjq6bqvrbzUAhUC4GMKHRR6AUkQ6AEINzAF|archive-date=November 4, 2017|df=mdy-all}}</ref> where [[atmospheric convection]] is the greatest. |

|||

This occurs from both the mixture of warmer and colder [[air mass]]es, as well as differences in moisture concentrations, and it generally happens at the [[Weather front|boundaries between them]]. The flow of warm ocean currents past drier land masses, such as the [[Gulf stream|Gulf Stream]], partially explains the elevated frequency of lightning in the [[Southeast United States]]. Because large bodies of water lack the topographic variation that would result in atmospheric mixing, lightning is notably less frequent over the world's oceans than over land. The [[north pole|North]] and [[south pole|South Poles]] are limited in their coverage of thunderstorms and therefore result in areas with the least lightning.{{Clarify|reason=absence of thunderstorms is similar to absence of lightning; an explanation of why are there less thunderstorms (lightning) above the poles would be more helpful|date=August 2019}} |

|||

As a result of their power, positive lightning strikes are considerably more dangerous. At the present time, [[aircraft]] are not designed to withstand such strikes, since their existence was unknown at the time standards were set, and the dangers unappreciated until the destruction of a [[glider]] in 1999 [http://web.archive.org/web/20041009230137/http://www.dft.gov.uk/stellent/groups/dft_avsafety/documents/page/dft_avsafety_500699.hcsp]. |

|||

In general, CG lightning flashes account for only 25% of all total lightning flashes worldwide. Since the base of a thunderstorm is usually negatively charged, this is where most CG lightning originates. This region is typically at the elevation where [[freezing level|freezing]] occurs within the cloud. Freezing, combined with collisions between ice and water, appears to be a critical part of the initial charge development and separation process. During wind-driven collisions, ice crystals tend to develop a positive charge, while a heavier, slushy mixture of ice and water (called [[graupel]]) develops a negative charge. Updrafts within a storm cloud separate the lighter ice crystals from the heavier graupel, causing the top region of the cloud to accumulate a positive [[space charge]] while the lower level accumulates a negative space charge. |

|||

Positive lightning is also now believed to have been responsible for the [[1963]] in-flight explosion and subsequent crash of [[Pan Am Flight 214]], a [[Boeing 707]]. Subsequently, aircraft operating in U.S. airspace have been required to have lightning discharge wicks to reduce the chances of a similar occurrence. |

|||

Because the concentrated charge within the cloud must exceed the insulating properties of air, and this increases proportionally to the distance between the cloud and the ground, the proportion of CG strikes (versus CC or IC discharges) becomes greater when the cloud is closer to the ground. In the tropics, where the freezing level is generally higher in the atmosphere, only 10% of lightning flashes are CG. At the latitude of Norway (around 60° North latitude), where the freezing elevation is lower, 50% of lightning is CG.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2001/ast05dec_1/|date=December 5, 2001|title=Where LightningStrikes|publisher=NASA Science. Science News.|access-date=July 5, 2010|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100716173018/http://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2001/ast05dec_1/|archive-date=July 16, 2010|df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref>[[#Uman|Uman (1986)]] Ch. 8, p. 68.</ref> |

|||

Positive lightning has also been shown to trigger the occurrence of [[#Sprites, elves, jets and other upper atmospheric lightning|upper atmospheric lightning]]. It tends to occur more frequently in [[winter storm]]s and at the end of a [[thunderstorm]]. |

|||

Lightning is usually produced by [[cumulonimbus]] clouds, which have bases that are typically {{cvt|1|-|2|km}} above the ground and tops up to {{convert|15|km|mi|abbr=on}} in height. |

|||

An average bolt of ''positive'' lightning carries a current of 300 kiloamperes (about ten times as much current as a bolt of negative lightning), transfers a charge of up to 300 [[coulomb]]s, has a potential difference up to 1 gigavolt (a thousand million volts), dissipates enough energy to light a 100 [[watt]] lightbulb for up to 95 years, and lasts for tens or hundreds of milliseconds. |

|||

The place on Earth where lightning occurs most often is over [[Lake Maracaibo]], wherein the [[Catatumbo lightning]] phenomenon produces 250 bolts of lightning a day.<ref name="TRMM">{{cite web |author1=R. I. Albrecht |author2=S. J. Goodman |author3=W. A. Petersen |author4=D. E. Buechler |author5=E. C. Bruning |author6=R. J. Blakeslee |author7=H. J. Christian |title=The 13 years of TRMM Lightning Imaging Sensor: From individual flash characteristics to decadal tendencies |url=https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20110015779/downloads/20110015779.pdf |website=NASA Technical Reports Server |access-date=23 November 2022}}</ref> This activity occurs on average, 297 days a year.<ref name=":2">Fischetti, M. (2016) [https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-world-s-top-lightning-hotspot-is-lake-maracaibo-in-venezuela/ Lightning Hotspots], Scientific American 314: 76 (May 2016)</ref><!-- This should probably be cite journal instead of cite web--> The second most lightning density is near the village of [[Kifuka]] in the mountains of the eastern [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]],<ref name=":1">{{cite web|url=http://www.wondermondo.com/Countries/Af/CongoDR/SudKivu/Kifuka.htm|title=Kifuka – place where lightning strikes most often|access-date=November 21, 2010|publisher=Wondermondo|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111001201900/http://www.wondermondo.com/Countries/Af/CongoDR/SudKivu/Kifuka.htm|archive-date=October 1, 2011|df=mdy-all|date=2010-11-07}}</ref> where the [[elevation]] is around {{convert|975|m|ft|-2|abbr=on}}. On average, this region receives {{convert|158|/km2/years|/sqmi/years|adj=pre|lightning strikes}}.<ref name="NOAA freq">{{cite web|url=http://sos.noaa.gov/datasets/Atmosphere/lightning.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080330025304/http://sos.noaa.gov/datasets/Atmosphere/lightning.html|archive-date=March 30, 2008|title=Annual Lightning Flash Rate |access-date=February 8, 2009|publisher=National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration}}</ref> Other lightning hotspots include [[Singapore]]<ref name="nea">{{cite web|url=http://app.nea.gov.sg/cms/htdocs/article.asp?pid=1203|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927224804/http://app.nea.gov.sg/cms/htdocs/article.asp?pid=1203|archive-date=2007-09-27|title=Lightning Activity in Singapore|access-date=September 24, 2007|publisher=National Environmental Agency|date=2002}}</ref> and [[Lightning Alley]] in Central [[Florida]].<ref name="alley">{{cite web|url=http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/lightning_alley.html|title=Staying Safe in Lightning Alley|access-date=September 24, 2007|publisher=NASA|date=January 3, 2007|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070713041430/http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/lightning_alley.html|archive-date=July 13, 2007|df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref name="fe">{{cite web|url=http://www.floridaenvironment.com/programs/fe00703.htm |title=Summer Lightning Ahead |access-date=September 24, 2007 |publisher=Florida Environment.com |date=2000 |author=Pierce, Kevin |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012160959/http://floridaenvironment.com/programs/fe00703.htm |archive-date=October 12, 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Lightning cloud to cloud (aka).jpg|thumb|Intracloud or possibly cloud-to-cloud lightning.]] |

|||

[[Heinz Kasemir]] first hypothesised that a lightning leader system actually develops in a '''bipolar''' fashion, with both a positive and a negative branching leader system connected at the system origin and containing a net zero charge. This process provides a means for the positive leader to conduct away the net negative charge collected during development, allowing the leader system to act as an extending polarised conductor. Such a polarised conductor would be able to maintain intense [[electric field]]s at its ends, supporting continued leader development in weak-background electric fields. |

|||

According to the [[World Meteorological Organization]], on April 29, 2020, a bolt 768 km (477.2 mi) long was observed in the southern U.S.—sixty km (37 mi) longer than the previous distance record (southern Brazil, October 31, 2018).<ref name=Phys_20220201/> A single flash in Uruguay and northern Argentina on June 18, 2020, lasted for 17.1 seconds—0.37 seconds longer than the previous record (March 4, 2019, also in northern Argentina).<ref name=Phys_20220201/> |

|||

During the eighties, flight tests showed that [[aircraft]] can trigger a bipolar [[stepped leader]] when crossing charged cloud areas. Many scientists think that positive and negative lightning in a cloud are actually bipolar lightning. |

|||

== Necessary conditions == |

|||

To spontaneously [[ionise]] air and conduct electricity across it, an [[electric field]] of [[field strength]] of approximately 2500 kilovolts per metre is required. However, measurements inside storm clouds to date have failed to locate fields this strong, with typical fields being between 100 and 400 kilovolts per metre. While there remains a possibility that researchers are failing to encounter the small high-strength regions of the large clouds, the odds of this are diminishing as further measurements continue to fall short. |

|||

{{main|Thunderstorm}} |

|||

In order for an [[electrostatic discharge]] to occur, two preconditions are necessary: first, a sufficiently high [[potential difference]] between two regions of space must exist, and second, a high-resistance medium must obstruct the free, unimpeded equalization of the opposite charges. The atmosphere provides the electrical insulation, or barrier, that prevents free equalization between charged regions of opposite polarity. |

|||

It is well understood that during a thunderstorm there is charge separation and aggregation in certain regions of the cloud; however, the exact processes by which this occurs are not fully understood.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1175/1520-0450(1993)032<0642:AROTEP>2.0.CO;2|volume=32|title=A Review of Thunderstorm Electrification Processes |last1=Saunders|first1=C. P. R.|journal=Journal of Applied Meteorology |issue=4 |pages=642–55|bibcode=1993JApMe..32..642S |year=1993|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

A theory by [[Alex Gurevich]] of the [[Lebedev Physical Institute]] in 1992 proposes that [[cosmic ray]]s may provide the beginnings of what he called a '''[[runaway breakdown]]'''. Cosmic rays strike an air molecule and release extremely energetic electrons having enhanced mean free paths of tens of centimeters. These strike other air molecules, releasing more electrons which are accelerated by the storm's electric field, forming a [[electron avalanche|chain reaction]] of long-trajectory electrons and creating a conductive [[Plasma (physics)|plasma]] many tens of meters in length. This was initially considered a fringe theory, but is now becoming [[mainstream]] because of the lack of other theories. |

|||

=== Electrical field generation === |

|||

It has been recently revealed that most lightning emits an intense burst of [[X-rays]] and/or [[gamma ray|gamma-rays]] which seem to be produced during the stepped-leader and dart-leader phases just before the stroke becomes visible. The X-ray bursts typically have a total duration of less than 100 microseconds and have energies extending up to nearly a few hundred [[keV]]. The presence of these high-energy events match and support the "runaway breakdown" theory, and were discovered through the examination of rocket-triggered lightning, and from [[satellite]] monitoring of natural lightning. |

|||

As a [[Cumulonimbus cloud|thundercloud]] moves over the surface of the Earth, an equal [[electric charge]], but of opposite polarity, is [[Electrostatic induction|induced]] on the Earth's surface underneath the cloud. The induced positive surface charge, when measured against a fixed point, will be small as the thundercloud approaches, increasing as the center of the storm arrives and dropping as the thundercloud passes. The referential value of the induced surface charge could be roughly represented as a bell curve. |

|||

The oppositely charged regions create an [[electric field]] within the air between them. This electric field varies in relation to the strength of the surface charge on the base of the thundercloud – the greater the accumulated charge, the higher the electrical field. |

|||

[[NASA]]'s [[RHESSI]] satellite typically reports 50 gamma-ray events per day, and many of these are strong enough to fit the theory. Additionally, [[Radio frequency|low-frequency radio emissions]] detected at ground level can detect lightning bolts from upwards of 4000 km away; combining these with gamma-ray burst events detected from above show overlapping positions and timing. |

|||

== Flashes and strikes == |

|||

There are problems with the "runaway breakdown" theory, however. While there seems to be a strong correlation between gamma-ray events and lightning, there are insufficient events detected to account for the amount of lightning occurring across the planet. Another issue is the amount of energy the theory states is required to initiate the breakdown. Cosmic rays of sufficient energy strike the atmosphere on average only once per 50 seconds per square kilometre. Measured X-ray burst intensity also falls short, with results indicating particle energy 1/20th of the theory's value. |

|||

The best-studied and understood form of lightning is cloud to ground (CG) lightning. Although more common, intra-cloud (IC) and cloud-to-cloud (CC) flashes are very difficult to study given there are no "physical" points to monitor inside the clouds. Also, given the very low probability of lightning striking the same point repeatedly and consistently, scientific inquiry is difficult even in areas of high CG frequency. |

|||

== Types of lightning == |

|||

Some lightning strikes take on particular characteristics, and scientists and the public have given names to these various types of lightning. |

|||

=== Lightning leaders === |

|||

=== Intracloud lightning, sheet lightning, anvil crawlers === |

|||

[[File: Lightning formation.gif|thumb|A downward leader travels towards earth, branching as it goes.]] |

|||

Intracloud lightning is the most common type of lightning which occurs completely inside one cumulonimbus cloud, and is commonly called an anvil crawler. Discharges of electricity in anvil crawlers travel up the sides of the [[cumulonimbus cloud]] branching out at the anvil top. |

|||

[[File:Leaderlightnig.gif|thumbnail|Lightning strike caused by the connection of two leaders, positive shown in blue and negative in red]] |

|||

In a process not well understood, a bidirectional channel of [[ionized]] air, called a "[[leader (spark)|leader]]", is initiated between oppositely-charged regions in a thundercloud. Leaders are electrically conductive channels of ionized gas that propagate through, or are otherwise attracted to, regions with a charge opposite of that of the leader tip. The negative end of the bidirectional leader fills a positive charge region, also called a well, inside the cloud while the positive end fills a negative charge well. Leaders often split, forming branches in a tree-like pattern.<ref>Ultraslow-motion video of stepped leader propagation: [http://www.ztresearch.com/ ztresearch.com] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100413125231/http://www.ztresearch.com/ |date=April 13, 2010 }}</ref> In addition, negative and some positive leaders travel in a discontinuous fashion, in a process called "stepping". The resulting jerky movement of the leaders can be readily observed in slow-motion videos of lightning flashes. |

|||

=== Cloud-to-ground lightning, anvil-to-ground lightning === |

|||

[[Image:Lightning over Oradea Romania 2.jpg|thumb|right|258px|Lightning over [[Oradea]] in [[Romania]]]] |

|||

[[Image:LightningToronto.jpg|thumb|250px|right|Lightning strike]] |

|||

Cloud-to-ground lightning is a great lightning discharge between a cumulonimbus cloud and the ground initiated by the downward-moving leader stroke. This is the second most common type of lightning. One special type of cloud-to-ground lightning is anvil-to-ground lightning, a form of positive lightning, since it emanates from the anvil top of a cumulonimbus cloud where the ice crystals are positively charged. In anvil-to-ground lightning, the leader stroke issues forth in a nearly horizontal direction till it veers toward the ground. These usually occur miles ahead of the main storm and will strike without warning on a sunny day. They are signs of an approaching storm and are known colloquially as "bolts from the blue". |

|||

It is possible for one end of the leader to fill the oppositely-charged well entirely while the other end is still active. When this happens, the leader end which filled the well may propagate outside of the thundercloud and result in either a cloud-to-air flash or a cloud-to-ground flash. In a typical cloud-to-ground flash, a bidirectional leader initiates between the main negative and lower positive charge regions in a thundercloud. The weaker positive charge region is filled quickly by the negative leader which then propagates toward the inductively-charged ground. |

|||

=== Bead lightning, ribbon lightning, staccato lightning === |

|||

Another special type of cloud-to-ground lightning is bead lightning. This is a regular cloud-to-ground stroke that contains a higher intensity of luminosity. When the discharge fades it leaves behind a ''string of beads'' effect for a brief moment in the leader channel. A third special type of cloud-to-ground lightning is ribbon lightning. These occur in thunderstorms where there are high cross winds and multiple return strokes. The winds will blow each successive return stroke slightly to one side of the previous return stoke, causing a ribbon effect. The last special type of cloud-to-ground lightning is staccato lightning, which is nothing more than a leader stroke with only one return stroke. |

|||

The positively and negatively charged leaders proceed in opposite directions, positive upwards within the cloud and [[Electric charge|negative]] towards the earth. Both ionic channels proceed, in their respective directions, in a number of successive spurts. Each leader "pools" ions at the leading tips, shooting out one or more new leaders, momentarily pooling again to concentrate charged ions, then shooting out another leader. The negative leader continues to propagate and split as it heads downward, often speeding up as it gets closer to the Earth's surface. |

|||

=== Cloud-to-cloud lightning === |

|||

Cloud-to-cloud or intercloud lightning is a somewhat rare type of discharge lightning between two or more completely separate cumulonimbus clouds. |

|||

About 90% of ionic channel lengths between "pools" are approximately {{convert|45|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length.<ref>Goulde, R.H. (1977) "The lightning conductor", pp. 545–576 in ''Lightning Protection'', R.H. Golde, Ed., ''Lightning, Vol. 2'', Academic Press.</ref> The establishment of the ionic channel takes a comparatively long amount of time (hundreds of [[millisecond]]s) in comparison to the resulting discharge, which occurs within a few dozen microseconds. The [[electric current]] needed to establish the channel, measured in the tens or hundreds of [[ampere]]s, is dwarfed by subsequent currents during the actual discharge. |

|||

=== Cloud-to-ground lightning === |

|||

Cloud-to-ground lightning is a lightning discharge between the ground and a cumulonimbus cloud from an upward-moving leader stroke. These thunderstorm clouds are formed wherever there is enough upward motion, instability in the vertical, and moisture to produce a deep cloud that reaches up to levels somewhat colder than freezing. These conditions are most often met in summer. Lightning occurs less frequently in the winter because there is not as much instability and moisture in the atmosphere as there is in the summer. These two ingredients work together to make convective storms that can produce lightning. Without instability and moisture, strong thunderstorms are unlikely. Lightning originates around 15,000 to 25,000 feet above sea level when raindrops are carried upward until some of them convert to ice. For reasons that are not widely agreed upon, a cloud-to-ground lightning flash originates in this mixed water and ice region. The charge then moves downward in 50 yard sections called step leaders. It keeps moving toward the ground in these steps and produces a channel along which charge is deposited. Eventually it encounters something on the ground that is a good connection. The circuit is complete at that time, and the charge is lowered from cloud-to-ground. The return stroke is a flow of charge(current) which produces luminosity much brighter than the part that came down. This entire event usually takes less than half a second. |

|||

Initiation of the lightning leader is not well understood. The electric field strength within the thundercloud is not typically large enough to initiate this process by itself.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s11214-008-9338-z|title=Charge Structure and Dynamics in Thunderstorms|date=2008|last1=Stolzenburg|first1=Maribeth|last2=Marshall|first2=Thomas C.|journal=Space Science Reviews|volume=137|issue=1–4|page=355|bibcode = 2008SSRv..137..355S |s2cid=119997418}}</ref> Many hypotheses have been proposed. One hypothesis postulates that showers of relativistic electrons are created by [[cosmic rays]] and are then accelerated to higher velocities via a process called [[runaway breakdown]]. As these relativistic electrons collide and ionize neutral air molecules, they initiate leader formation. Another hypothesis involves locally enhanced electric fields being formed near elongated water droplets or ice crystals.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1029/2007JD009036|title=A brief review of the problem of lightning initiation and a hypothesis of initial lightning leader formation|date=2008|last1=Petersen|first1=Danyal|last2=Bailey|first2=Matthew|last3=Beasley|first3=William H.|last4=Hallett|first4=John|journal=Journal of Geophysical Research|volume=113|issue=D17|pages=D17205|bibcode = 2008JGRD..11317205P }}</ref> [[Percolation theory]], especially for the case of biased percolation,<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1103/PhysRevE.81.011102|pmid=20365318|title=Biased percolation on scale-free networks|date=2010|last1=Hooyberghs|first1=Hans|last2=Van Schaeybroeck|first2=Bert|last3=Moreira|first3=André A.|last4=Andrade|first4=José S.|last5=Herrmann|first5=Hans J.|last6=Indekeu|first6=Joseph O.|journal=Physical Review E|volume=81|issue=1|page=011102|bibcode = 2010PhRvE..81a1102H |arxiv = 0908.3786 |s2cid=7872437}}</ref> {{clarify| what does 'biased percolation' mean?|date= July 2013}} describes random connectivity phenomena, which produce an evolution of connected structures similar to that of lightning strikes. A streamer avalanche model<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Griffiths|first1=R. F.|last2=Phelps|first2=C. T.|date=1976|title=A model for lightning initiation arising from positive corona streamer development|journal=Journal of Geophysical Research|volume=81|issue=21|pages=3671–3676|doi=10.1029/JC081i021p03671|bibcode=1976JGR....81.3671G}}</ref> has recently been favored by observational data taken by LOFAR during storms.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Sterpka|first1=Christopher|last2=Dwyer|first2=J|last3=Liu|first3=N|last4=Hare|first4=B M|last5=Scholten|first5=O|last6=Buitink|first6=S|last7=Ter Veen|first7=S|last8=Nelles|first8=A|date=2021-11-24|title=The Spontaneous Nature of Lightning Initiation Revealed|journal=Ess Open Archive ePrints |volume=105 |issue=23 |pages=GL095511 |doi=10.1002/essoar.10508882.1|bibcode=2021GeoRL..4895511S |s2cid=244646368|url=https://bib-pubdb1.desy.de/record/474239 |hdl=2066/242824|hdl-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Lewton|first=Thomas|date=2021-12-20|title=Detailed Footage Finally Reveals What Triggers Lightning|url=https://www.quantamagazine.org/radio-telescope-reveals-how-lightning-begins-20211220/|access-date=2021-12-21|website=Quanta Magazine}}</ref> |

|||

=== Heat lightning''' or '''summer lightning === |

|||

Heat lightning (or, in the UK, "summer lightning") is nothing more than the faint flashes of lightning on the [[horizon]] from distant thunderstorms. Heat lightning was named because it often occurs on hot summer nights. Heat lightning can be an early warning sign that thunderstorms are approaching. In [[Florida]], heat lightning is often seen out over the water at night, the remnants of storms that formed during the day along a [[seabreeze]] [[cold front|front]] coming in from the opposite coast. |

|||

=== Upward streamers === |

|||

Some cases of "heat lightning" can be explained by the [[refraction]] of sound by bodies of air with different [[density|densities]]. An observer may see nearby lightning, but the sound from the discharge is refracted over his head by a change in the temperature, and therefore the density, of the air around him. As a result, the lightning discharge appears to be silent. [http://whyfiles.org/137lightning/index.html] |

|||

[[File:Upwards streamer from pool cover.jpg| thumb|220x124px | right | Upwards streamer emanating from the top of a pool cover]] |

|||

When a stepped leader approaches the ground, the presence of opposite charges on the ground enhances the strength of the [[electric field]]. The electric field is strongest on grounded objects whose tops are closest to the base of the thundercloud, such as trees and tall buildings. If the electric field is strong enough, a positively charged ionic channel, called a positive or upward [[Streamer discharge|streamer]], can develop from these points. This was first theorized by Heinz Kasemir.<ref>Kasemir, H. W. (1950) "Qualitative Übersicht über Potential-, Feld- und Ladungsverhaltnisse Bei einer Blitzentladung in der Gewitterwolke" (Qualitative survey of the potential, field and charge conditions during a lightning discharge in the thunderstorm cloud) in ''Das Gewitter'' (The Thunderstorm), H. Israel, ed., Leipzig, Germany: [[Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft]].</ref><ref>Ruhnke, Lothar H. (June 7, 2007) "[https://archive.today/20110611231459/http://www.physicstoday.org/obits/notice_157.shtml Death notice: Heinz Wolfram Kasemir]". Physics Today.</ref><ref name="SA-Stephan">{{cite web |last1=Stephan |first1=Karl |title=The Man Who Understood Lightning |url=https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/the-man-who-understood-lightning/ |publisher=Scientific American |access-date=26 June 2020 |date=March 3, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

As negatively charged leaders approach, increasing the localized electric field strength, grounded objects already experiencing [[corona discharge]] will [[Corona breakdown|exceed a threshold]] and form upward streamers. |

|||

=== Ball lightning === |

|||

{{main|Ball lightning}} |

|||

Ball lightning is described as a floating, illuminated ''ball'' that occurs during thunderstorms. They can be fast moving, slow moving or nearly stationary. Some make hissing or crackling noises or no noise at all. Some have been known to pass through windows and even dissipate with a bang. Ball lightning has been described by [[eyewitness]]es but rarely, if ever, recorded by [[meteorologist]]s. |

|||

=== Attachment === |

|||

The engineer [[Nikola Tesla]] wrote, "I have succeeded in determining the mode of their formation and producing them artificially" (''Electrical World and Engineer'', 5 March 1904). There is some speculation that [[electrical breakdown]] and [[arcing]] of [[cotton]] and [[gutta-percha]] wire insulation used by Tesla may have been a contributing factor, since some theories of ball lightning require the involvement of carbonaceous materials. Some later [[experiment]]ers have been able to briefly produce small luminous balls by igniting carbon-containing materials atop sparking [[Tesla Coil]]s. |

|||

Once a downward leader connects to an available upward leader, a process referred to as attachment, a low-resistance path is formed and discharge may occur. Photographs have been taken in which unattached streamers are clearly visible. The unattached downward leaders are also visible in branched lightning, none of which are connected to the earth, although it may appear they are. High-speed videos can show the attachment process in progress.<ref>{{Cite journal |doi = 10.1002/2017GL072796|title = Lightning attachment process to common buildings|journal = Geophysical Research Letters|volume = 44|issue = 9|pages = 4368–4375|year = 2017|last1 = Saba|first1 = M. M. F.|last2 = Paiva|first2 = A. R.|last3 = Schumann|first3 = C.|last4 = Ferro|first4 = M. A. S.|last5 = Naccarato|first5 = K. P.|last6 = Silva|first6 = J. C. O.|last7 = Siqueira|first7 = F. V. C.|last8 = Custódio|first8 = D. M.|bibcode = 2017GeoRL..44.4368S|doi-access = free}}</ref> |

|||

=== Discharge === |

|||

Several theories have been advanced to describe ball lightning, with none being universally accepted. Any complete theory of ball lightning must be able to describe the wide range of reported properties, such as those described in Singer's book "The Nature of Ball Lightning" and also more contemporary research. Japanese research shows that ball lightning has been seen several times without any connection to stormy weather or lightning. |

|||

====Return stroke==== |

|||

Ball lightning field properties are more extensive than realised by many scientists not working in this field. The typical fireball diameter is usually standardised as 20–30 cm, but ball lightning several meters in diameter has been reported (Singer). A recent photograph by a [[Queensland]] ranger, Brett Porter, showed a fireball that was estimated to be 100 meters in diameter. The photograph has appeared in the scientific journal ''Transactions of the Royal Society''. The object was a glowing globular zone (the breakdown zone?) with a long, twisting, rope-like projection (the funnel?). |

|||

{{redirect|Return stroke}} |

|||

[[File:Lightnings sequence 2 animation-wcag.gif|thumb|High-speed photography showing different parts of a lightning flash during the discharge process as seen in [[Toulouse]], France.]] |

|||

Once a conductive channel bridges the air gap between the negative charge excess in the cloud and the positive surface charge excess below, there is a large drop in resistance across the lightning channel. Electrons accelerate rapidly as a result in a zone beginning at the point of attachment, which expands across the entire leader network at up to one third of the speed of light.<ref name =Ulman2001>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DgHCAgAAQBAJ|title=The lightning discharge|access-date=September 1, 2020|publisher=Courier Corporation|author=Uman, M. A.| date=2001|isbn=9780486151984}}</ref> This is the "return stroke" and it is the most [[Luminous intensity|luminous]] and noticeable part of the lightning discharge. |

|||

Fireballs have been seen in tornadoes, and they have also split apart into two or more separate balls and recombined. Fireballs have carved trenches in the [[peat]] [[swamps]] in [[Ireland]]. Vertically linked fireballs have been reported. One theory that may account for this wider spectrum of observational evidence is the idea of [[combustion]] inside the low-velocity region of axisymmetric (spherical) [[vortex]] breakdown of a natural vortex (e.g., the '[[Hill's spherical vortex]]'). The scientist Coleman was the first to propose this theory in 1993 in ''Weather'', a publication of the [[Royal Meteorological Society]]. |

|||

A large electric charge flows along the plasma channel, from the cloud to the ground, neutralising the positive ground charge as electrons flow away from the strike point to the surrounding area. This huge surge of current creates large radial voltage differences along the surface of the ground. Called step potentials,{{citation needed|date=September 2020}} they are responsible for more injuries and deaths in groups of people or of other animals than the strike itself.<ref>Deamer, Kacey (August 30, 2016) [https://www.livescience.com/55916-why-reindeer-killed-by-lightning.html More Than 300 Reindeer Killed By Lightning: Here's Why]. ''Live Science''</ref> Electricity takes every path available to it.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Path of Least Resistance|url=http://ecmweb.com/content/path-least-resistance|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160104215214/http://ecmweb.com/content/path-least-resistance|archive-date=January 4, 2016|df=mdy-all|date=July 2001|access-date=January 9, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

Ball lightning is hardly ever seen. In fact, there are only a few pictures of it. |

|||

Such step potentials will often cause current to flow through one leg and out another, electrocuting an unlucky human or animal standing near the point where the lightning strikes. |

|||

The electric current of the return stroke averages 30 kiloamperes for a typical negative CG flash, often referred to as "negative CG" lightning. In some cases, a ground-to-cloud (GC) lightning flash may originate from a positively charged region on the ground below a storm. These discharges normally originate from the tops of very tall structures, such as communications antennas. The rate at which the return stroke current travels has been found to be around 100,000 km/s (one-third of the speed of light).<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Idone | first1 = V. P. | last2 = Orville | first2 = R. E. | last3 = Mach | first3 = D. M. | last4 = Rust | first4 = W. D. | title = The propagation speed of a positive lightning return stroke | doi = 10.1029/GL014i011p01150 | journal = Geophysical Research Letters | volume = 14 | issue = 11 | page = 1150 | year = 1987 |bibcode = 1987GeoRL..14.1150I | url = https://zenodo.org/record/1231386 }}</ref> |

|||

[[St Elmo's fire]] was correctly identified by Franklin as electrical in nature. It is not the same as [[ball lightning]]. |

|||

The massive flow of electric current occurring during the return stroke combined with the rate at which it occurs (measured in microseconds) rapidly [[superheating|superheats]] the completed leader channel, forming a highly electrically conductive plasma channel. The core temperature of the plasma during the return stroke may exceed {{convert|50,000|F|C|order=flip}},<ref>{{Cite web |last=US Department of Commerce |first=NOAA |title=Understanding Lightning: Thunder |url=https://www.weather.gov/safety/lightning-science-thunder#:~:text=The%20lightning%20discharge%20heats%20the,the%20surface%20of%20the%20sun |access-date=2023-12-15 |website=www.weather.gov |language=EN-US}}</ref> causing it to radiate with a brilliant, blue-white color. Once the electric current stops flowing, the channel cools and dissipates over tens or hundreds of milliseconds, often disappearing as fragmented patches of glowing gas. The nearly instantaneous heating during the return stroke causes the air to expand explosively, producing a powerful [[shock wave]] which is heard as [[#Thunder|thunder]]. |

|||

=== Sprites, elves, jets, and other upper atmospheric lightning === |

|||

Reports by scientists of strange lightning phenomena above storms date back to at least 1886. However, it is only in recent years that fuller investigations have been made. This has sometimes been called ''megalightning''. |

|||

====Re-strike==== |

|||

''Sprites'' are now well-documented electrical discharges that occur high above the [[cumulonimbus]] cloud of an active [[thunderstorm]]. They appear as luminous reddish-orange, [[neon]]-like flashes, last longer than normal lower stratospheric discharges (typically around 17 milliseconds), and are usually spawned by discharges of positive lightning between the cloud and the ground. Sprites can occur up to 50 km from the location of the lightning strike, and with a time delay of up to 100 milliseconds. Sprites usually occur in clusters of two or more simultaneous vertical discharges, typically extending from 65 to 75 km (40 to 47 miles) above the earth, with or without less intense filaments reaching above and below. Sprites are preceded by a ''sprite halo'' that forms because of heating and [[ionisation]] less than 1 millisecond before the sprite. Sprites were first photographed on July 6, 1989, by scientists from the [[University of Minnesota]] and named after the mischievous sprites in the plays of [[Shakespeare]]. |

|||

High-speed videos (examined frame-by-frame) show that most negative CG lightning flashes are made up of 3 or 4 individual strokes, though there may be as many as 30.<ref>[[#Uman|Uman (1986)]] Ch. 5, p. 41.</ref> |

|||

Each re-strike is separated by a relatively large amount of time, typically 40 to 50 milliseconds, as other charged regions in the cloud are discharged in subsequent strokes. Re-strikes often cause a noticeable "[[strobe light]]" effect.<ref name="uman">[[#Uman|Uman (1986)]] pp. 103–110.</ref> |

|||

Recent research [http://www.uh.edu/admin/media/nr/102002/beringsprites100702.html] carried out at the [[University of Houston]] in 2002 indicates that some normal (negative) lightning discharges produce a ''sprite halo'', the precursor of a sprite, and that ''every'' lightning bolt between cloud and ground attempts to produce a sprite or a sprite halo. Research in 2004 by scientists from [[Tohoku University]] found that [[very low frequency]] emissions occur at the same time as the sprite, indicating that a discharge within the cloud may generate the sprites [http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2004GL021943]. |

|||

To understand why multiple return strokes utilize the same lightning channel, one needs to understand the behavior of positive leaders, which a typical ground flash effectively becomes following the negative leader's connection with the ground. Positive leaders decay more rapidly than negative leaders do. For reasons not well understood, bidirectional leaders tend to initiate on the tips of the decayed positive leaders in which the negative end attempts to re-ionize the leader network. These leaders, also called ''recoil leaders'', usually decay shortly after their formation. When they do manage to make contact with a conductive portion of the main leader network, a return stroke-like process occurs and a ''dart leader'' travels across all or a portion of the length of the original leader. The dart leaders making connections with the ground are what cause a majority of subsequent return strokes.<ref name="Warner">{{cite web |url=https://ztresearch.blog/education/ground-flashes/ |title=Ground Flashes |last=Warner |first=Tom |website=ZT Research |access-date=2017-11-09|date=2017-05-06 }}</ref> |

|||

''Blue jets'' differ from sprites in that they project from the top of the cumulonimbus above a thunderstorm, typically in a narrow cone, to the lowest levels of the [[ionosphere]] 40 to 50 km (25 to 30 miles) above the earth. They are also brighter than sprites and, as implied by their name, are blue in colour. They were first recorded on [[October 21]], [[1989]], on a video taken from the [[space shuttle]] as it passed over Australia. |

|||

Each successive stroke is preceded by intermediate dart leader strokes that have a faster rise time but lower amplitude than the initial return stroke. Each subsequent stroke usually re-uses the discharge channel taken by the previous one, but the channel may be offset from its previous position as wind displaces the hot channel.<ref>[[#Uman|Uman (1986)]] Ch. 9, p. 78.</ref> |

|||

''Elves'' often appear as a dim, flattened, expanding glow around 400 km (250 miles) in diameter that lasts for, typically, just one millisecond [http://hbar.stanford.edu/cpbl/elves]. They occur in the ionosphere 100 km (60 miles) above the ground over thunderstorms. Their colour was a puzzle for some time, but is now believed to be a red hue. Elves were first recorded on another shuttle mission, this time recorded off [[French Guiana]] on [[October 7]], [[1990]]. [[Elves]] is a frivolous [[acronym]] for ''E''missions of ''L''ight and ''V''ery Low Frequency Perturbations From ''E''lectromagnetic Pulse ''S''ources. This refers to the process by which the light is generated; the excitation of [[nitrogen]] molecules due to [[electron]] collisions (the electrons having been energised by the electromagnetic pulse caused by a positive lightning bolt). |

|||

Since recoil and dart leader processes do not occur on negative leaders, subsequent return strokes very seldom utilize the same channel on positive ground flashes which are explained later in the article.<ref name="Warner"/> |

|||

On [[September 14]], [[2001]], scientists at the [[Arecibo Observatory]] photographed a huge jet double the height of those previously observed, reaching around 80 km (50 miles) into the atmosphere. The jet was located above a thunderstorm over the ocean, and lasted under a second. Lightning was initially observed travelling up at around 50,000 m/s in a similar way to a typical ''blue jet'', but then divided in two and sped at 250,000 m/s to the ionosphere, where they spread out in a bright burst of light. |

|||

====Transient currents during flash==== |

|||

On [[July 22]], [[2002]], five gigantic jets between 60 and 70 km (35 to 45 miles) in length were observed over the [[South China Sea]] from [[Taiwan]], reported in ''Nature'' [http://sprite.phys.ncku.edu.tw/new/news/0626_presss/nature01759_r.pdf]. The jets lasted under a second, with shapes likened by the researchers to giant trees and carrots. |

|||

The electric current within a typical negative CG lightning discharge rises very quickly to its peak value in 1–10 microseconds, then decays more slowly over 50–200 microseconds. The transient nature of the current within a lightning flash results in several phenomena that need to be addressed in the effective protection of ground-based structures. Rapidly changing currents tend to travel on the surface of a conductor, in what is called the [[skin effect]], unlike direct currents, which "flow-through" the entire conductor like water through a hose. Hence, conductors used in the protection of facilities tend to be multi-stranded, with small wires woven together. This increases the total bundle [[surface area]] in inverse proportion to the individual strand radius, for a fixed total [[Cross section (geometry)|cross-sectional area]]. |

|||

The rapidly changing currents also create [[Electromagnetic pulse|electromagnetic pulses (EMPs)]] that radiate outward from the ionic channel. This is a characteristic of all electrical discharges. The radiated pulses rapidly weaken as their distance from the origin increases. However, if they pass over conductive elements such as power lines, communication lines, or metallic pipes, they may induce a current which travels outward to its termination. The surge current is inversely related to the surge impedance: the higher in impedance, the lower the current.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://sites.ieee.org/sas-pesias/files/2016/03/Lightning-Protection-and-Transient-Overvoltage_Rogerio-Verdolin.pdf|title=Lightning Protection and Transient Overvoltage | VERDOLIN SOLUTIONS INC. | HIGH VOLTAGE POWER ENGINEERING SERVICES}}</ref> This is the [[Voltage spike|surge]] that, more often than not, results in the destruction of delicate [[electronics]], [[electrical appliance]]s, or [[electric motor]]s. Devices known as [[Surge protector|surge protectors (SPD) or transient voltage surge suppressors (TVSS)]] attached in parallel with these lines can detect the lightning flash's transient irregular current, and, through alteration of its physical properties, route the spike to an attached [[Electrical ground|earthing ground]], thereby protecting the equipment from damage. |

|||

Researchers have speculated that such forms of upper atmospheric lightning may play a role in the formation of the [[ozone layer]]. |

|||

== Types == |

|||

Three primary types of lightning are defined by the "starting" and "ending" points of a flash channel. |

|||