Sainte-Marie de Valmagne Abbey

| Valmagne Abbey | |

|---|---|

NE corner of the cloister courtyard, with a wall of bells |

|

| location |

|

| Coordinates: | 43 ° 29 '13.1 " N , 3 ° 33' 44.2" E |

| Serial number according to Janauschek |

352 |

| founding year | 1138 by Benedictines |

| Cistercian since | 1144 |

| Year of dissolution / annulment |

1789 |

| Mother monastery | Bonnevaux Monastery (Dauphiné) |

| Primary Abbey | Citeaux monastery |

The Abbey of Sainte-Marie de Valmagne is a former Cistercian monastery near Villeveyrac in the arrondissement of Montpellier in the Hérault department in the Occitania region in southern France, around 13 km east of Pézenas , just under 40 kilometers northeast of Béziers, around 30 kilometers southwest of the center of Montpellier and around 8 kilometers north of the Étang de Thau .

history

founding

(Pp. 1–20)

In 1138 the powerful feudal lords of Cabrières (Hérault) called on the monks of the Benedictine monastery of Ardorel (near Castres ) to found a monastery in the diocese of Agde . Ardorel belonged to Fontevrault in the diocese of Albi . At that time it had become too small for the numerous monks and so many of their brothers, under the leadership of Abbot Foulques, followed the call and made their way over the mountains of Lacaune and Espinouser to the Mediterranean.

They found a suitable place for their construction project north of the Etang du Thau on a wasteland about 24 kilometers in diameter, which was called Tortoriera or Toutourière and was populated only by wild animals. There was a feudal district called “Vallis Magna” (large valley) or Villa Magna (large house) near the vigorously bubbling “ Diana source”. It is also assumed that some of the marble columns come from the chapter house of a former Roman villa, namely this "Villa Magna". The location was protected from the strong north winds by jagged rock cliffs. In addition, the Roman road " Via Domitia " was in the immediate vicinity , which in antiquity connected the province of " Gallia Narbonensis " with the Roman Empire and was at the same time the fastest land connection between Rome and the Iberian Peninsula.

The year 1138 is now considered to be the founding year and Raimond I. Trencavel, Vice Count of Béziers (died 1167) as the main benefactor and founder of the Abbey of Sainte Marie of Valmagne.

In addition to Raimond I, a number of pious citizens from the area took part in the land foundation. The vice count soon confirmed the foundation with its rights. His father, Bernard Aton IV., Had already donated the Ardorel monastery and Raimond himself had been taught and raised by Benedictine monks. The following year, on August 25, 1139, Bishop Raimond von Agde made the donation legally binding. The abbey was to submit to the rules of the order of Benedict of Nursia and to submit to the authorities of Ardorel and Cadouin in the Périgord.

Valmagne was originally founded as a Benedictine monastery. But as early as 1144, only six years later, the second abbot Peter began to seek a connection to Cîteaux , the original monastery of the Cistercians. Since Robert von Molesme (also called Robert von Cîteaux) founded the Novum Monasterium , the new monastery and later Citeaux in 1098 , the still young order experienced a tremendous boom. The religious goal of the Cistercians was to return to the original rules of St. Benedict, such as poverty, penance and seclusion.

Connection to Cîteaux

The annexation of Valmagnes to Cîteaux was not without particular problems. Abbot Peter asked Pope Eugene III. on behalf of his monks, to release Valmagne from the vow of obedience to the abbots of Ardorel and Cadouin, which already happened in 1145. From then on, the Pope placed Valmagne under the control of the Cistercian monastery Bona Vallis (= Bonnevaux ) in the Dauphiné. But the two abbots did not give up the aspiring Abbey of Valmagne without resistance. Their main benefactor Raimond I. Trencavel supported Abbot Peter. However, his mother, who had been significantly involved in the Ardorels Foundation through her husband and, because of this bond, wanted Valmagne to be connected to Ardorel, was against her son.

In 1159, twenty-one years after the foundation by the Benedictines, Pope Hadrian IV decreed the final annexation of Valmagnes to Citeaux. In order to familiarize the monks with the rules of the Cistercians and to instruct them in them, monks from Bonneveaux came to Valmagne, checked the foundation documents and checked whether the monastery met the conditions required by Bernard von Clairvaux: absolute solitude, water, fertile soil. Because the express demands on a Cistercian monastery were: The monastery should contain everything necessary within its walls, such as drinking water, a mill, a garden and workshops of various craftsmen, so that the monks have to avoid leaving the enclosure.

According to the Charter of Mercy of the third abbot of Citeaux, Etienne Harting, the commandment of perfect equality applied to all friars: “Although we are physically scattered in all directions, we remain united in our souls ... so that none in our deeds differs from the other, but each live with the same mercy according to the same rules and customs. "

Romanesque abbey building

According to the rules, the abbey church for eighty monks was built on the highest point of the site. Although the monks were trained in a wide variety of trades, from tailors to carpenter to blacksmith, in order to be able to repair and manufacture as much as possible, it was not possible to completely do without the participation of external specialists. Especially with the new construction of such a large monastery, you had to rely on the help of external builders and assistants from the area, especially you needed a skilled stonemason.

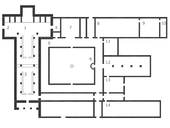

No remains or documents are known of the structures of the Romanesque church. In contrast, large parts of the Romanesque monastery are still preserved today, such as the entire east wing of the convent building (from the sacristy to the former work rooms of the monks), the southern section of the west wing (rooms for the lay brothers) and probably the arched arcades of the cloister. The former cellar in the northern area of the west wing may have belonged to this construction phase. The sources give no information about the existence of other Romanesque components, for example in the south or west of the cloister or on the upper floor. This also applies to the original covering of the presumably single-storey cloister.

The abbey church should be designed as simply as possible, on the plan of a Latin cross. In the south of the church there was the cloister, which was enclosed on three sides by convent buildings. Its east wing housed the armarium (library), the sacristy, the chapter house, the parlatorium (consulting room, also treatment room for the sick), and the scriptorium. On its upper floor was the dormitory, from which perhaps a separate room for the abbot was separated, with direct access to the church via a staircase. The south wing housed the calefactorium (warming room), the monks' refectorium (dining room) and the kitchen. The southern area of the west wing was reserved for lay brothers and occasional guests. The lay brothers were thus assigned closest to the basse-cour , the agricultural sector.

One of the essential tasks of the monks, in addition to prayer, meditation and contemplation and the manual work required in everyday life, was carried out in the scriptorium. Some of the monks wrote down prayer and song texts that were needed for the communal mass celebrations. This gradually resulted in an extensive choir and convent library. Other monks dedicated themselves to the copying of all traditional texts of all kinds and thus contributed to the fact that numerous historical sources and texts have been preserved.

For the necessary contact with the outside world, for example for work in the field and in the vineyard, for the cattle and all activities that had to be carried out outside the monastery walls, there were the so-called lay brothers, also called conversations (from the Latin conversus ) who were peasants from the area who had renounced their normal lives but had not taken monastic vows. Quite a few of them stayed away from the monastery for most of the year, from the sowing in spring through the summer to the harvest in autumn, and lived and worked in so-called granges (manors, barns), farms that belonged to the monastery, but also many Could be miles away.

Ascent

Valmagne grew, the number of monks and lay brothers increased and the spatial expansion grew noticeably and considerably. Land donations and so-called privileges, privileges and preferential usage rights, lined up one after the other. For example, the Count of Roussillon granted the right to operate a fishing boat on the nearby Etang de Thau, Peter von Pézénas allowed the grain to be milled in his mills and more. Valmagne received fiefs from Marcouine, Fonduce, Valautre, and Veirac, privileges in Cabrials, Mèze, Paulhan, Ganvern, and Loupian. William of Montpellier granted all members of the order, and in particular Valmagne, duty-free throughout the city, Jean Abbé granted tax-exemption in 1175 for all the lands of Raimond de Toulouse and the four mills of Paulhan on the Herault. Valmagne has received so much attention that it is impossible to list everything here. This made it one of the wealthiest and most powerful monasteries in the south of France.

During this time, the monasteries were not only under the protection of the Holy See in Rome, but also under that of the king and rulers. So Valmagne was under the special protection of the family of its founder, Raimond Trencavel. Since this family was owed to the King of Mallorca , who later became King of Aragon , Valmagne was automatically subject to his protection. In the Middle Ages this was a highly complex system and network of mutual dependencies, hierarchical structures and protections.

The early period of Valmagne is one of immense wealth and expansion. The 12th century is called the "Golden Age" of the Cistercians and is the epitome of the order's success.

The construction of the Romanesque monastery, the great rise and growth of Valmagnes' wealth coincided with the heyday of the pilgrimages to the tomb of the Apostle James the Elder in Santiago de Compostela in the first half of the 12th century, when hundreds of thousands of pilgrims annually attack the Pyrenees moved south. During this time, mainly monastic communities, such as the Cistercians, organized the pilgrimage. Four main routes and a network of secondary routes were formed, on which churches, monasteries, hospices , hostels and also cemeteries were built or expanded.

Valmagne was also a very important station on the Way of St. James near the southernmost main route of the Via Tolosana , with the starting point Arles , via Toulouse and Oloron further south-west through Spain, and the monastic community was able to participate in the willingness of the pilgrims to donate with its new church and its relics.

Heyday, a large Gothic church was built

(Pp. 20–29)

Even if the archives have burned or otherwise disappeared, today's architectural findings provide clear evidence of the abbey's heyday and prosperity. Nor can Valmagne deny the traces of its eventful history that can be seen everywhere on the building.

In the early days of Valmagne, its abbots were directly elected by the monks of the monastery, which later changed. In 1245 Bertrand d'Auriac was appointed Abbot of Valmagne, and given the mandate to control and supervise the monks of Saint-Félix de Montceaux and the Benedictines of Vignogoul for the church . His work on Valmagne dates back to the time of the last Trencavel, under King Louis the Saint . In 1247 he received the grounds of the Jewish cemetery in Montpellier from King Jacques of Aragon, feudal lord of Mallorca and Montpellier, in order to build a college on it. At that time the city already had a renowned university and the college, the “High School of Valmagne”, soon enjoyed great popularity.

For a long time, the monks of Valmagne, especially in view of the large numbers of pilgrims to Spain, had thought of building a new, and above all, larger church. The significantly increased number of monks also required larger areas for the buildings. Ultimately, you want to create a visible expression of power and success. Bernhard von Clairvaux died over 100 years ago in 1152 and some things had changed. Finally, in 1257, the Bishop of Agde, Raymond Fabri, gave his permission to build a new abbey church, although the "old" one only existed for 120 years.

In the meantime, however, the streams of pilgrims to Spain had declined in the second half of the 12th century when the dispute between England and France over Aquitaine began. Further wars in the 13th century caused the pilgrimage to break off completely. Nevertheless, the wealth of Valmagnes allowed a new building.

Bertrand d'Auriac was a very active abbot who wanted to keep up with the times. He brought builders and stonemasons from northern France to Valmagne. In the north, especially on the Ile de France, they were already in the high Gothic phase, while in the south the churches were still relatively modest in the Romanesque style. The Gothic, however, was more suitable for the visible demonstration of power and wealth, highly ambitious on a generous floor plan, with huge windows, which it transformed into light-flooded palaces.

Twenty years before the Gothic found its way into the cathedral buildings in southern France, a Gothic monastery church was built in Valmagne, which presented itself as a cathedral (bishopric), built on a basilic floor plan in the form of a Latin cross, with a stylistic finesse and delicacy that in the south is unparalleled, the first example of Northern French High Gothic in the Languedoc.

The overall construction is extremely delicate and filigree and is particularly suitable for emphasizing the vertical. The three-aisled, seven-bay floor plan with its wide ambulatory choir with numerous radial chapels on the choir head and side chapels on the north side is very reminiscent of that of a large pilgrim church.

A number of details on this building point to very trained builders, for example in the choir, for example on the trick that makes the choir appear much longer than it actually is. The widths of the pointed arches of the choir arcades are narrowing from the outside to the apex of the choir apse. This leads to the aforementioned perspective illusion. The almond-shaped cross-section of the choir pillars, which makes the columns appear slimmer and finer than those with a round or square cross-section, is also rare.

The structure was enormous and, on top of that, represented a financial risk. To maintain such a construction site, it required a large number of trained craftsmen and assistants, all of whom had to be housed, fed and remunerated. It was not inconvenient for the next abbot of Valmagne, Jean III., To transfer the rights to the bridge at Lunel in 1274 by King Jacques of Aragon. A lucrative stroke of luck, because the bridge lay exactly on the route of the cami saliné, which led from Frontignan via Auroux, Mudaison, Candiargue to Nimes, over which all salt transports were carried out.

Since the decree of Nicolas IV in 1277, the indulgence trade flourished and also proved to be a profitable business for Valmagne. The bull of May 7, 1291 (Orvieto) granted an indulgence of one year and forty days to pilgrims who visited the church of Valmagne on the feast of St. Bernard, the four feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary and during the respective festival weeks. The abuse of the flourishing indulgence trade prompted Luther to make his first foray.

After a construction period of at least fifty years, around 1310, maybe a little later, the Gothic monastery church was completed. The barely 120-year-old Romanesque building was demolished in sections as they were rebuilt, so that Holy Mass can continue to be celebrated in it largely undisturbed.

In the meantime, however, the convent had also become too small and also needed an expansion. In contrast to the church, in which the Romanesque church building was demolished without hesitation in order to build the new one on parts of its foundation walls, most of the Romanesque parts of the monastery were preserved, for example the armarium (library in a wall niche in the east wing), the sacristy, the chapter house, the parlatorium and the scriptorium, as well as the rooms of the lay brothers in the west wing, as well as the arched arcatures of the cloister to the courtyard and the chapter house. The outer walls of the south and west gallery of the cloister, like the wall of the north gallery, belong to the Gothic construction phase from the beginning of the 13th century. The vaulting of the cloister with cross-ribbed vaults also belongs to this section. The vaulting of the south gallery and parts of the east gallery vault are said to have been built at the beginning of the 14th century. In the east gallery there is a curious transition from the round arched arcatures of the chapter hall in the Romanesque wall to the pointed arches of the gallery vault above, whereby the arch widths do not correspond to one another at all. This creates a disordered impression, a visible sign of various construction phases.

The sources do not provide any information about the additional extensions to the convent building in the Gothic section, for example in the area of the south and west wings or on the upper floor. The current upper floor of the cloister seems to have been extended in a later phase, apart from the rooms of the dormitory.

As with its convent buildings, the eventful history of Valmagne can be read today particularly in its abbey church. The huge windows above the arcades of the central nave were bricked up in 1635 in the course of extensive renovation work, as were most of the lancet windows of the choir apse, the radial chapels, the huge rosette of the west facade, as well as the rosettes of the transept arms. What a light-flooded room this church must have been until then, gloriously shining in the glaring sun of the south, only to be compared with the northern French Gothic cathedrals, so very different from the sacred buildings of Languedoc, where they are more in front of the light of the sun close.

Valmagne, like all other monasteries and the whole country, was shaken by terrible economic, political and social crises. At the beginning of the 14th century there was a widespread famine in Europe and fifty years later the whole of Languedoc was starving. The fields could no longer be tilled due to devastating storms. The " black plague " came from the Crimea and in 1348 swept the people there in droves. The number of monks decreased rapidly. Some fled in fear and could no longer integrate into the strict rules of the order on their return.

The battles of the Hundred Years War devastated the lands and caused unimaginable damage. But even in the so-called "quiet times" one could not feel safe. For example, bands of robbers attacked the monasteries, tortured and massacred the monks. A certain Seguin de Badafol terrorized the region in such a way that the abbot of Valmagne felt compelled to fortify the monastery.

The sad times of destruction that struck many monasteries and much of the country continued. Valmagne was weakened economically and had to part with several estates, first of Fondouce and Marcouine. But even their sale could not save Valmagne. To survive, the abbey lost one property after another.

After these disasters, outsiders had the impression that the monasteries were poorly run economically. The monastic communities were blamed for the crisis and accused of mismanagement. The result was that the monks were no longer allowed to choose the abbots from among their ranks, but instead they were appointed by the king and given the appropriate rights by the pope. In addition to economic consequences, this had the desirable side effect that the Church and the Pope gained control of the monasteries. According to canon law, this procedure is called a coming .

From 1477 the fortunes of Valmagne were controlled by such abbots, not elected but appointed. The first was generously endowed with donations from a number of benefactors, nobles from Languedoc, including the Lauzières and Villeneuve families.

In 1560 the wars of religion began. The region was shaken by battles between Catholics and Protestants, with bitter battles, including in Agde and other places where the population resisted and wanted to remain Catholic.

Valmagne was not spared either. In 1571 a tragic incident loomed. The monastery was abandoned by an abbot Vincent Concomblet de Saint-Séverin. Although he was the nephew of the arch-Catholic bishop of Agde, Aymerie de Saint-Séverin, he had defected to supporters of the reform. He had his camps in nearby Montagnac, which was completely in the hands of the Reformed, and in Lésignan-l'Evêque, of which he was governor. From there he constantly recruited new farmers and deserters for his troops at the gates of “his” monastery and caused a bloodbath among “his” monks and the population seeking protection. Records prove the massacre and say that he did not shrink back from hanging the eighty-year-old monk Nonenque, ("Archives de l'Hérault - Gallia Christina")

The wars of religion raged in the French kingdom for more than half a century. Edict followed edict (Amboise, Poitiers, Nantes 1589), peace after peace (Longjumeau, Saint Germain, Beaulieu), massacre after massacre (Vassy, Saint-Barthélémy), king after king (Henri II and his three sons).

Abbot Saint-Severin finally died under unexplained circumstances. The next abbot of Valmagne, Pierre VIII. De Guers, was not appointed until 1578. In the meantime the abbey was deserted and exposed to the marauding hordes. The governor of Languedoc, Damville, who had appropriated his brother's title Duke of Montmorency after the death of his brother, tyrannized the region from his home in Pézénas and also raged in Valmagne.

The abbey survived these attacks, albeit in a deplorable condition. In 1575 all the stained glass windows in the church were destroyed and the panes lost forever. There were neither windows nor doors, large openings everywhere, and the church interior was exposed to wind and weather. Last but not least, the chapter council, which was under pressure, decided to sell more lands.

It would be almost a century before Valmagne regained some of its former glory. In 1624 the famous builder Jean Thoma was brought to Valmagne and commissioned to repair the cloister vaults "without destroying anything". Much was lost forever, like the colorful window panes. The monastery could no longer afford the costly work of northern French stained glass, which would have withstood the storms and storms of Languedoc, and instead commissioned master mason Michel Gaudonnet from Saint Pargoire in 1635 to “wall up all but two of the windows”. Today, this step is considered incomprehensible, since the windows could have been fitted with cheaper clear glass as an alternative.

The de Guers and de Vairac families have made a special contribution to the restoration of Valmagne. Their coats of arms adorn the base of the marble statue of the Virgin, which is currently in the choir apse. The coat of arms of the widow de Guers, Madame de Paulhan, can be found on the fountain basin in the cloister courtyard. This was rebuilt by the Hugolz brothers, master well builders from Saint-Jean de Fos. Their mandate was: "... to restore the Griffouls fountain that used to flow in the monastery of the abbey in question, with the same old course that flows through the great church".

Restoration and glory under Cardinal de Bonzi

(Pp. 29–32)

During the 17th century, part of the cloister galleries were vaulted again. The date 1610 can be found on a keystone in the east gallery opposite the Parlatorium.

The second half of the 17th century was dominated by abbots of Italian origin. The first Italian abbot was Victor Siri, a friend of Richelieu and Jules Mazarin . He hardly lived in Valmagne and left the administration to the prior Dom Maffre, who continued the restoration work and, for example, had the western cloister gallery vaulted again in 1663. He also initiated the rebuilding of the refectory, the south wing of the convent building, where his name and date can be found on an arch: "Debit N. Dom Maffre Prieur des Moines 1665". Contrary to the rule, the refectory does not extend at right angles to the nave, but parallel to it.

Pointing the way for the further fate of Valmagnes was Abbot Pierre de Bonzi, a cardinal from the Florentine nobility. He was powerful and brilliant. The Bonzi family had five bishops in a hundred years. King Louis XIV appointed him Bishop of Béziers when the bishopric became vacant due to the death of his uncle Clement de Bonzi.

Pierre de Bonzi enjoyed the absolute trust of the king and showered him with titles, and commissioned him with special negotiations and special missions, which took him as a special ambassador to Venice, Poland and Spain. He became archbishop of Toulouse and cardinal in 1672. He was also the confessor of Queen Maria Theresa. In 1673 Louis XIV appointed him Archbishop of Narbonne and appointed him Governor of the Languedoc States. As abbot, he directed the fortunes of Valmagne from 1680 to 1697.

Cardinal de Bonzi played an important role for the whole of Languedoc. Saint-Simon reported that for a long time he was the real king because of his authority, the trust he enjoyed at court and his love for the province.

Valmagne was his favorite place. The sophisticated prelate had an important personal fortune, which he invested in maintaining and expanding Valmagne for the good of Valmagne. He turned the abbey into a real bishopric, added one floor to the entire convent building with cloister and converted the dormitory on the first floor of the east wing into a spacious corridor, from which the rooms with alcoves and oratorios (prayer room) open off decorated trumeaus are separated. A spacious stone staircase led up to the rooms with a wide arch and was bordered by magnificent wrought-iron railings. It still exists today. The Parlatorium was given a door that led into a magnificent park “a la française”.

The number of monks had risen to almost 300 at that time.

His frequent stays in Versailles and the festivities in the gardens designed by André Le Nôtre certainly inspired the cardinal when decorating Valmagne: from a huge terrace, facing south, two symmetrical stairs led down to a garden with a long water basin in it in the middle and at the end a statue of Neptune. She stood in a pool of water that was caught by a shell. At the feet of the statue a dolphin splashing water into the pool through its mouth. Magnificent vases, decorated with fruits and heads, adorned the garden. You can find them today in the chapter house.

If you believe the traditions, the cardinal lived a life in Valmagne like at court. At that time they were far from monastic rigor. A crowd of domestic workers took care of the physical well-being. One lived excessively, with every conceivable luxury. The cardinal hosted many receptions in Valmagne and treated his guests royally. The then War Minister Louis XIV, Louvois, who made a stop on Valmagne on the way to Barèges in 1680, wrote impressedly to his cousin, the Marquis de Tailladet, that he had stopped in Valmagne and had “found the greatest dinner here, that you can align at all ”.

There is no question that at this time one was further removed than ever from the rules of St. Bernard. The manners were permissive in every respect. E. Leroy Ladune, in his history of Languedoc, expressed himself in no way tenderly about the cardinal and dubbed him “a refined and sensual Ecclesiast, lover of handsome men and beautiful women, who mercilessly abused his power”. His blatant love affair with Madame de Ganges was at least not inclined to give him a halo.

However, it cannot be understood that in this prosperous phase of the abbey the walling of the church windows was not reversed and glazing was installed instead.

Last abbots, revolution and its consequences

(Pp. 32–34)

In 1697, Cardinal de Bonzi gave the abbey to his nephew Armand-Pierre de la Croix de Castries, Archdeacon of Narbonne. He was the son of one of his sisters who was married to the Marquis de Castries. A few years later, on July 11, 1703, the cardinal died in Montpellier.

The new abbot continued Valmagne in the style of his uncle, generously and luxuriously. A warm welcome was given on the occasion of the visit of the Duke of Burgundy and the Duke of Berry. Both had accompanied their brother, the young Duke of Anjou and future King Philip V of Spain, to the Spanish border and stopped in Valmagne on the return journey to Versailles.

The last three abbots of Valmagne were Monseigneur de Buisson de Beauteville, very popular for his kindness, Pierre François de Jouffroy d'Abbans and Armand Pierre de Puységur.

Immediately before the revolution , the abbey was heavily in debt. One of the main reasons for this was that the last two abbots never lived on site, but claimed a high income from Valmagne.

A dispute broke out between the monks of Valmagne and the consuls of Montagnac over the sovereignty of the monastery land. In 1786 the consuls had overwritten the entry in the wealth tax register from Valmagne to Montagnac. In 1789 there was a transaction in the chapter house of the monastery in which the monks finally had to renounce their territorial sovereignty. In return, the consuls waived the payment of the levies of 29 annuites that had been demanded until then.

The abbey's financial situation was deplorable. On November 13, 1789, the National Assembly, with the consent of the king, passed a decree in which the clergy required a written declaration of all income, property, real estate and fiefdoms. Prior Dom Desbies took over the listing of the monastery property. It resulted in a deficit of 2,206 pounds and 6 dinars and debts of 15,000 pounds, payable in two annual installments to the abbot of Puységur. The list of the convent property and the generated income names, among other things, Vairac, the chicken farm, the lands in Silvéréal, the manors Mas del Novi, le Sacristain and others, but costs and debts were many times higher. The precarious situation in Valmagne was plain to see.

Since the community of monks had decreased significantly in the last few years, the cultivation of the land was a burden on the lay brothers alone. The land lay fallow and decayed. Valmagne once numbered between 200 and 300 monks. In 1786 the prior had only three monks with him, plus a porter, a gardener, a cook, a kitchen boy, a hunter and a child who acted as an altar boy. They held out until 1790, about a year after the outbreak of the revolution, when the prior fled with the last three monks, with the gold and silver and the most valuable furniture. Valmagne was given up to the mob.

And he didn't hesitate long. Only a few days later the cheering pack of farmers from the neighboring villages attacked the orphaned abbey and devastated everything, burned documents, documents, records, books, furniture and pictures.

Like most of the monasteries in France, the convent and church with the remaining lands and branches became state property. However, the state was not interested in the costly maintenance of such properties and tried to capitalize on them as quickly as possible. On May 23, 1791, the district of Béziers awarded the contract to the winemaker Monsieur Granier for 130,000 pounds. He acquired the convent buildings, the church, the chicken farm, the land and the le Sacristain estate. The new owner converted the church into a wine cellar. In the yokes of the side aisles and in the choir chapels he placed huge wooden pods made of Russian oak, in which the wine matured. You have been in this place for over 200 years. In the process, walls were drawn into the high arcades of the central nave, which seemingly divided the side aisles into two floors. Their “parapets” close horizontally just above their arches. In the lower "storey", large, arched openings are cut out to enclose the wine barrels more closely. The high aisles behind it kept their height.

Some visitors may be shocked that all of the sacred furnishings have disappeared and the church is used so profanely. The critics may bear in mind, however, that this magnificent church and the enchanting monastery have only survived because Valmagne was only abandoned for barely a year and was then constantly managed and maintained. As a result, the abbey was spared the fate of so many sister monasteries that ended up as quarries and are now only in ruins or no longer exist. In contrast, after eight and a half centuries of eventful history, Valmagne stands before us today as a relatively intact architectural ensemble.

Valmagne - family-owned for over 150 years

(Pp. 34–38)

After Monsieur Granier's death, the monastery and land were put up for auction by his widow and heirs. By concordat of 1801, the church had to renounce all claims to all of its nationalized goods. Nevertheless, the bishop's approval had been obtained and in July 1838 Valmagne changed hands in the court of Montpellier. "The new owner was Henri-Amédée-Mercure de Turenne."

The monastery has been owned by the same family ever since. It was extensively restored in the second half of the 19th century. But in our time, maintaining such a structure has become increasingly difficult. The responsibility for such a unique historical and architectural heritage is fascinating and frightening at the same time. Throughout the year there are daily visits, guided tours through the magnificent Gothic church and the light-flooded cloister, the epitome of Mediterranean beauty and serenity and at the same time full of solemn meditative tranquility. This cloister certainly has nothing in common with the strictness required by St. Bernard, but is more reminiscent of exquisite Tuscan gardens. Valmagne owes the lovely Mediterranean atmosphere to the influence of its Florentine abbots, above all Pierre de Bonzi, who knew how to create the light, lines and shapes here in Languedoc that are reminiscent of Giotto's landscape .

The deafening rush of water draws visitors to the Griffouls Fountain, across from the monks' refectory. It is surrounded by an octagonal gallery and covered by an open dome that is still being worked on. Here Romanesque and poetry unite and enchant the viewer.

The chapter house, which is covered with a wide groin vault in a self-supporting manner, without being supported by a central pillar, also deserves special attention. (see detailed description in the section Buildings / Interior)

On the bench of the chapter house stone fragments are exhibited, the scenes of an Annunciation, the entry into Jerusalem, a crucifixion and a descent from the cross and others can be guessed. In all likelihood, these stones come from a rood screen, a stone barrier that once separated the church interior into an eastern part, which was reserved for monks, and a western part for lay people and lay brothers. However, this must have existed in the Romanesque church, as the ambulatory was also allowed to be visited by lay people to worship the relics in the chapels. It is believed that these fragments were used for the staircase that led from the " Porte des Matines " to the dormitory on the upper floor directly into the southern arm of the transept.

The monk's refectory from the 17th century was extensively renovated in the 19th century. It impresses with its size as well as its furnishings, such as the high ribbed vaults and the magnificent renaissance fireplace. which comes from the Château de Cavillargues.

The Valmagne Monastery has been a listed building by the Ministry of Culture since April 11, 1947 and has also been open to tourists since 1975.

Since 1980 almost all the roofs of the buildings have been re-covered. The rooms of Cardinal de Bonzi, which were storage rooms in the 19th century, have been furnished in a contemporary way and are now used as living rooms.

Valmagne has been an important winery for over 200 years. This is one of the reasons why his church is called the “Cathedral of Wine”.

Buildings

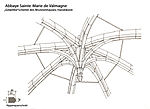

Floor plan and elevation

Dimensions approx, without wall protrusions,

Measured from drawing and extrapolated:

- church

- Overall length (outside): 44.80 m

- Length of nave, from facade to transept (outside): 23.20 m

- Width of the nave, at floor level (outside): 12.70 m

- Width central nave, between services (inside): 5.70 m

- Height of central nave, in the apex (inside): 23.50 m

- Height of aisles, in the apex (inside): 11.00 m

- Length of the transept (outside): 17.50 m

- Width transept (inside): 4.70 m

- Depth choir apse (inside): 4.40 m

- Width of the ambulatory (inside): 1.90 m

- Narthex, length × width (outside): 12.80 × 3.20 m

- Convent building

- Length of the east wing, from the transept arm (outside): 52.60 m

- Width east wing, without cloister (outside): 6.10 m

- Length of the cloister courtyard, SN direction: 14.40 m

- Width of the cloister courtyard, direction WO: 13.30 m

- Width east gallery (inside): 2.6 m

- Width west gallery (inside): 2.20 m

- Width north and south gallery (inside): 2.40 m

- Height of galleries, at the apex: 5.34 m

- Length of the south wing (between the west and east galleries): 20.30 m

- Width south wing, without cloister (outside): 5.60 m

- Length of west wing, northern section: 16.60 m

- Width of the west wing, northern section, without cloister (outside): 3.6 m

- Length of the west wing, southern section (outside): 20.70 m

- Width west wing, southern section (outside): 5.80 m

Abbey church

(P. 10) The stately Gothic church, which was built in the second half of the 13th century without taking over any parts of the Romanesque predecessor structure, has been almost completely preserved and faces east.

However, it has lost the originally light-flooded appearance of the almost complete windowing of the outer walls in the wars of religion.

As a result, in 1635, when the large window openings could not be renewed for lack of sufficient financial means, almost all of them were bricked up instead. Today's darkness of the interior no longer corresponds in any way to the ideas of Gothic architecture and changes it seriously to its disadvantage.

A second change in Gothic architecture took place towards the end of the 18th century when, in connection with the installation of the large wine fudges in the side aisles, the high arcades were narrowed by the insertion of wall sections and apparently divided into two floors.

The two above measures are said to have been carried out to stabilize the delicate and "fragile" construction.

The church stands on the ground plan of a basilica with a three-aisled and seven-bay nave, with a cantilevered transept, choir bay, and an ambulatory choir , which is closed off by a chapel wreath in the east.

Outward appearance

Narthex

(P. 9) In front of the facade of the nave there is a three-part west building in the manner of a westwork . It is as long as the width of the nave and about as deep as the width of the nave yokes. The ground floor is the actual narthex, a vestibule , a vestibule in which the monks received the catechumens who were preparing for baptism . They were considered unclean and were not allowed to enter the church. In Valmagne, masses were also celebrated here for the believers in the area: the interior of the church was also closed to them because they did not belong to the religious community.

The middle section is as wide and about half as high as the central nave. It is flanked by two towers that are square in plan. Which end just below the ridge height of the central nave and are covered there by gently sloping pitched roofs, which are covered with hollow tiles in Roman format, also known as monk-nun tiles. The middle section is covered with a flat roof that can be walked on, the front edge of which is covered by a stone balustrade in the style of Louis XIII. completed, which is surmounted in the middle by a stone cross. In the facade wall above this terrace a huge circular oculus (Latin for eye) was originally cut out, which is also known as the "ox eye". Its diameter almost corresponds to the inner width of the nave. From the round window opening, which was once equipped with artistic tracery in the form of a rose window, with glass paintings, only the contour of its outer edge remains after the brickwork. To replace the large opening, a slender, pointed arched window with Gothic tracery has been cut out in the brickwork, which is a good meter away from the former edge of the rose window above and below.

A large, slightly pointed opening is cut out axially in the middle section of the front wall, the reveal edges of which are broken with wide bevels. Your crown is well above the middle height of the wall. Further to the outside, a large, slender, pointed-arched window with tracery, but without glazing, is cut out in the axes of the towers. Above these windows there are two small rectangular openings in the tower walls, one above the other, in the form of loopholes . Such openings can also be found at the same height on the outer side walls of the towers. In the east walls of the towers, door openings are recessed above the aisle roofs, from which one can access these roofs. In the southeast corner of the south tower, a circular spiral staircase was added, of which only half of a stair tower with a hexagonal floor plan is visible on the outside. Some slender loopholes are also embedded in these walls. The tower closes at the height of the tower eaves with a hexagonal flat sloping pyramid roof.

The towers and the walk-on terrace above the narthex are obviously part of the defense equipment of the monastery, which was built in the course of the Hundred Years War in the middle of the 14th century.

Longhouse

From the outside, the basilic three-aisled elevation (cross-section) of the nave is immediately noticeable, with the central nave being about twice as wide and twice as high as the side aisles. Above the flat, sloping, walk-on aisle roofs rise up buttresses that subdivide the nave into seven bays in the transverse direction, just like the girdle arches and pillars inside .

The buttresses each consist of a buttress, the upper end of which leans against the central nave wall just below the eaves as an extension of the respective belt arch and the lower end of which merges into the significantly wider vertical buttresses. The underside is rounded in the shape of a quarter circle and the upper side is inclined outwards by 45 degrees along its entire length and is covered with stone slabs shaped like a gable roof.

On the north side of the church, the buttresses in the lower area are also the partition walls of the seven side chapels located there. The flat sloping roofs of the chapels that can be walked on are not quite as high as those of the original north gallery of the cloister. Above these roofs, the depths of the pillars remain completely intact until the transition into the buttress arches. The roof-like covering of the buttress arches bends horizontally there and is made much wider to the end of the pillar.

The “ridge” of these covers is designed as an open drainage channel over the entire length, which ends at the lower end in a wide-spreading gargoyle. The upper end of the gutters is extended to under the eaves cornice by a partly steeply sloping section. The function of these gutters can hardly be explained today, as there are no water-collecting devices under the eaves that would lead the rainwater from the bricks to the upper ends of the gutters on the buttresses.

On the opposite south side of the church, the deep buttresses do not work because the adjacent north gallery of the cloister does not allow them. As an alternative, the lower part of the outer wall of the aisle has been considerably widened up to the level of the gallery vault and the pillars above are flush with the gallery-side wall surface. In addition, these pillars are supported by the vault of the cloister and its belt arches.

On both sides of the nave, a large ogival window was originally cut out in each yoke just above the roof connections of the aisles, the apex of which almost reached under the eaves of the central nave. They once contained elaborate tracery with stained glass. In the middle of the 17th century, the destroyed windows were bricked up, of which slightly receding arcade niches are still left today. Similar to the rose window in the facade, a significantly smaller ogival window with simple tracery has been cut out on each side in the four yoke. A small ogival window is cut out axially in the walls of the chapels, but the sources do not provide any information about their condition.

The central nave is covered by a gable roof with a flat incline of about twenty degrees, which is covered with reddish monk-nun tiles, which protrude slightly at the eaves above a barely protruding cornice. This applies to almost all roofs of the monastery, with the exception of the accessible roof areas of the side aisles, the ambulatory and the terrace above the narthex.

Transept

The transept is somewhat narrower than the central nave, its eaves and roofs are at the same level as those of the choir and merge with one another. The roof surfaces meet with diagonal grooves. The building corners of the north arm of the transept are stiffened with strong, multi-tiered buttresses that reach under the eaves. In the southern arm, this is done by the walls of the adjoining convent wing and also by the stair towers, which slightly protrude from the eaves.

In the gable walls there was originally a circular ocular high above, the diameter of which was just about the width of the inner nave. Similar to the rosette in the facade, the openings have been lined up again, whereby larger parts of the tracery could be integrated. Significantly smaller ogival windows with tracery replace the oculi.

In the west and east walls of the transept arms, two large ogival windows were originally cut out above the aisle roofs, which corresponded to those of the central nave. Like these, they are completely walled up. In front of the pillars between these windows, a slender buttress protrudes under the eaves.

The gable wall of the southern arm of the transept is flanked above the adjoining roofs of the convent building by two slender stair turrets containing spiral staircases. The one on the southeast corner is hexagonal and is similar to the one on the southern tower of the west building. The one on the southwest corner is circular, via which one reaches the bell wall, which protrudes high above the roof of the transept. The bell wall stands on the equally thick outer wall of the south aisle in yoke seven and is as wide as this. At the level of the eaves there is a caesura in the form of a slight recess on all sides. A twin arcade is cut out above it, with slender ogival openings. Above this, the width of the bell wall tapers and has another, but smaller, ogival opening there. The tops of the stepped wall are beveled outward at approximately 45 degrees. The bells are freely suspended in the three openings.

Choir head

The choir head is initially like an eastern extension of the nave by a yoke beyond the transept, the so-called choir yoke, with the same elevation and the same buttress. On the ridge of the roof above the Chorjoch sits a six-foot-high hexagonal roof turret made of masonry with a hexagonal pyramid roof. The actual choir head connects to the choir bay, from the central choir apse, which is grouped almost semicircular around the choir with seven wall sections, which is covered by a piece of gable roof and further by a five-sided, partial pyramid roof. The roofs have the same elevation, inclinations and eaves as in the nave.

The same applies to the ambulatory surrounding the apse, the seven polygonal sections of which correspond to the side aisles. These sections are divided radially by almost the same buttresses above the roof. Seven radial chapels are inserted between the deep buttresses, the polygonal roofs of which connect to the roofs of the gallery. Its free outer walls consist of three sections each, which are bent twice under each other and supported there by slim buttresses.

In the wall sections of the choir bay and the choir apse, pointed arched lancet windows were cut out above the roofs of the gallery, the widths of which were adapted to the changing widths of the wall sections. All but three of these windows are walled up. In the wall sections of the radial chapels, three, outside only two, very slim lancet windows were cut out, all of which are now walled up.

Interior of the church

As with the external appearance, when assessing the Gothic substance of the architecture, one must also think away from the extensive post-Gothic changes inside the church, especially the walling of most of the windows and the partial closing of the arcatures of the partition walls.

Narthex

In the narthex on the ground floor, which extends over the entire width of the nave, one can clearly see the division into three sections, which exactly corresponds to the three-aisled division of the nave. The subdivisions are made as an extension of the partition walls by massive arcades with a polygonal cross-section and five equally wide free sides, without marking their arches. The vaults are as high as those of the aisles. The middle section corresponds to the central nave and is covered by a three-part ribbed vault, the middle section is almost twice as wide as the two outer ones.

Their ribs have cross-sections of three round profiles that are separated by two narrow fillets. The belt arches separating them have the same cross-sections. The two outer room sections correspond to those of the side aisles and their vaults have the same ribs as in the middle section. The ribs and belt arches stand on different figuratively sculpted consoles, which are arranged a little lower than the apex of the outer portal opening. One depicts three head portraits , in the middle the crowned head of the contemporary Louis the Saint (1214–1270), another shows three upper bodies, that of a monk, who is flanked by boatmen. These representations contradict the building rules of the Cistercians.

The narthex is well lit by several openings in the west wall that cannot be closed by glazed windows or door leaves. The large, high, slightly pointed portal opening is embedded in the building axis, the reveal edges of which are broken by wide bevels. The side reveals merge into the arched reveals without a break. The opening is flanked by ogival twin markings, the arches of which rest on triple columns standing one behind the other, which are equipped with carved capitals, fighters and bases and stand on parapets. A large, slender, pointed arched window with tracery is cut out in the outer sections of the room.

In the middle section, the actual main portal of the church is embedded as a five-tiered archivolt portal. The rectangular portal opening is covered by five set back archivolts, which are supported by columns of the same type. The gradations are divided into numerous round profiles that are separated by fillets. In the case of the two inner archivolts, these spaces are decorated with plant sculptures. The arch approaches of the archivolts are marked with profiled fighters and the columns stand on angular consoles. The outer archivolt is covered by another, which ends slightly higher than the others and stands there on protruding carved consoles.

For the original function of the narthex see section: Appearance.

Longhouse

The nave has a basilica elevation in which the central nave is about twice as wide and twice as high as the side aisles. It is divided into seven yokes in the transverse direction by belt arches on services and pillars. The ships are extremely slim. In the very high aisles one could easily have moved galleries . Perhaps, however, they did not do this because during the construction of the Gothic church the pilgrimages to St. James had already decreased considerably, and then even completely collapsed.

The ogival arcades in the partition walls have apex heights that remain just below the apex heights of the aisle vaults. Their reveals, which are still visible in the arch area, have segment arch-shaped cross-sections, the edges of which are simply profiled. The slight receding of the subsequently drawn-in wall parts to just above the arches shows that once the rounded reveals, at the same time as lateral pillars, reached right down to the floor. These cross-sections are reminiscent of the almond-shaped cross-sections of the pillars of the choir apse. The reveals are marked at the arches of transom profiles, of which only short remnants are visible. On the two pillar sides facing the ships, three semicircular slender services emerge, the middle one a little further than the one flanking it. The services are separated by receding narrow fillets. They stand on a meter high pedestal with polygonal cross-sections, which are graduated several times in height.

The arch approaches of the belt arches, cross ribs and shield arches are marked by transom profiles. The cross ribbed vaults of the ships, which carry the vaulted gussets, rise above this. The ribs and belt arches have the same cross-sections, each made of a rectangle that is accompanied by a three-quarter round bar on the underside in the middle. Ribs and belt arches meet in the crowns of the vault: In the central nave and choir, these are particularly lavishly decorated and, as they were originally, colored.

The decor and state of preservation of the keystones from the second half of the 13th century to the beginning of the 14th century are unusual for a Cistercian church. The topics presented are completely different. Some show decorative elements, such as leaf rosettes, or four heads arranged radially, while others have biblical content, such as the coronation of Mary in the vault of the choir apse. Apart from the fact that this motif was very popular at the end of the 12th century, this outstanding place also deserves it because Mary is the patroness of the church and the entire monastery. Other keystones show scenes from the history of the monastery, such as the two saints Benedict and Bernhard, side by side, with a crosier in hand, or Saint Benedict with his pupil Placidus. Some depictions are difficult to decipher, such as the crowned head on a green background, possibly the portrait of a benefactor, at least not a monk, as he does not wear a habit .

A good one meter above the apex of the partition arcades runs the entire length of the central nave, a horizontal narrow cantilevered cornice on which the large pointed arched windows of the central nave once stood. On the outside, between the profile and the apex of the arch, the vaults with the very flat roofs of the aisles connect. In the aisle walls there was a small oculus with tracery in the shape of a quatrefoil in each yoke high above . Almost all the windows are still walled up today. The oculi in the south aisle have already disappeared behind the subsequently added upper floor of the north gallery of the cloister.

On the outer wall of the north aisle, a side chapel with a rectangular floor plan is built into each yoke, which is separated from the towering buttresses of the outer buttresses. They are covered by groin vaults. In bays 1 to 3 the chapels open into the side aisles with large pointed arcades, in chapels 4 to 7 with simple small doors. A small ogival window with tracery was cut out in the center of each yoke in the outer walls. In the outer wall of the south aisle there is a rectangular doorway in the 1st yoke into the west wing of the convent building and in the 7th yoke a similar doorway into the cloister.

The wall parts that were subsequently drawn into the partition arcades make the side aisles appear as two-storey with a gallery. They reach just above the arch approaches. The arcades created below are hardly wider than the wooden pods placed in them. The wedge arch covering it has the shape of a circular arc section, the ends of which rest on simply profiled cantilever cornices.

The partition arcades in bays 1, 2 and 7 are completely walled up except for wicket doors. The side aisles were also mostly subdivided with transverse walls under the belt arches.

- Gallery longhouse

Transept with crossing

The transept immediately follows the nave, into which the naves with their arcades open. In the rectangular crossing, the central nave and the transept penetrate one another. It is flanked by the extensions of the aisles, which are closed in the south and north by the outer sections of the transept arms.

The crossing is emphasized by four strong bundles of pillars, the largest in the church. Numerous three-quarter round services surround a powerful core. On three corners they are thicker than the rest in between. The pillar sides of the partition arcades and the chorus arcades are rounded like those of the arcade reveals. The services are divided by intervals into which narrow profiles are inserted. The pillars stand on appropriately structured, multi-tiered bases with polygonal cross-sections.

Above the affected arches, which are marked by transom profiles as in the nave, the cross ribs, belt arches and shield arches of the cross rib vaults, which carry the vault gussets and meet in keystones, all in the same way as in the nave.

The four pillars that stand in extension of the outer walls of the aisles and their vaulted sections are not constructed much differently. However, they limit and bilaterally to other components.

The transept was originally a particularly lavishly lit section of space. Each transept arm was brightly lit by four large ogival windows, similar to those of the central nave, and a large oculus in the transept gable, all with tracery.

In the gable wall of the south arm of the transept, the Porte des Matines can be seen, which, in connection with a staircase, gave the monks direct access from the dormitory on the upper floor to the church.

In the opposite north wall of the transept arm there is still the Porte des Morts , the dead gate, to the burial place, the cemetery of the monastery. Not only were the monks buried there, but also many patrons and donors, who had made a special contribution to the monastery, found their final resting place there.

Choir head

The choir bay, which adjoins the transept in the east, has a similar elevation to the transept and is about as wide as the bays of the nave. The middle section has an elongated rectangular plan. The floor plan of the sections in the extension of the side aisles tapers slightly to the east, as a transition to the somewhat narrower ambulatory. The floor plans of the outer sections are correspondingly polygonal. The two arcades on the side of the central section correspond to those of the central nave when they were not yet walled up. The arcades in the outer sections are covered by belt arches, as we know them from the ships.

The choir apse adjoins the middle part of the choir bay in the same width and height. Its curve is enclosed by seven wall sections that are about as high as the central nave walls. Their widths steadily decrease from the outside towards the middle. In the lower wall sections there are pointed arches, which are separated by pillars with an elegant almond-shaped cross-section. The rounded sides of the pillars are continued above the arches to the apex. Some of the pillars are adorned by horizontal, sometimes diagonally extending, leaf ribbons. The arch approaches are marked by sculpted fighter profiles. These arcades are as high as the partition arcades, their widths decrease from the outside to the center according to the width of the wall section. The two pointed pillar edges are accompanied by slender three-quarter round bars, which are continued above the arches as belt arches of the walkway and cross ribs of the apse with corresponding linings. The latter meet in the already mentioned circular keystone. A piece above the apex of the choir apse arcades ran the horizontal cantilevered cornice that is already known from the partition walls. On top of it stood the ogival windows, the width of which steadily decreased from the outside towards the center. They reach under the arches of the vault. Only three of them with the accompanying tracery have survived. The widths of the wall sections, which decrease towards the middle, and their openings are intended to suggest a greater depth of the choir, an optical illusion.

The choir apse is enclosed on the outside by the ambulatory, which consists of seven identical sections with symmetrical trapezoidal floor plans. The belt arches separating them are an extension of the radially arranged cross ribs of the choir apse. The cross ribs of the vaults each meet at an outwardly shifted point. All services of the ambulatory and the chapels are on the already familiar pedestals.

The ambulatory is surrounded by a chapel wreath made up of seven radial chapels , which are separated by the vertical pillars of the buttresses of the choir apse. At the ends of the buttresses on the circumferential side, bundled pillars are arranged, the services of which support the connecting arches and cross ribs of the gallery and the chapels. The U-shaped floor plans of the chapels are each surrounded by five wall sections that bend polygonally below one another. The chapels are covered by ribbed vaults, the radially extending ribs of which meet in a center starting from the kink points. In the wall sections of the chapels there were three, and in the outer two lancet windows with tracery, all but one of which are now walled up.

- Gallery choir head

Convent building

Outward appearance

Today's two-storey, slightly rectangular cloister was probably originally single-storey and was enclosed in the north by the south wall of the church and in the west and south by single-storey convent buildings.The east wing of the convent building was at least partially two-storey from the start, with the dormitory on the upper floor. The cloister was covered with inwardly inclined monopitch roofs, which partially united with the outwardly inclined monopitch roofs of the convent buildings to form gable roofs.

The convent buildings with their cloister are almost all two-story today, with the exception of the single-story south wing, the monks' refectory . All roofs are inclined by about twenty degrees and covered with monk and nun tiles, as with the church. The north and south galleries of the cloister are covered with inward sloping pent roofs, the roofs of which are at the level of the eaves of the north aisle. The west and east galleries, together with the accompanying convent rooms, are covered with gable roofs whose eaves and ridge heights match those of the north and south galleries. The south wing of the refectory connects to the south gallery, the pent roof ridge of which lies a good bit below that of the south gallery. The southern sections of the east and west wings, which are covered with gable roofs, extend far beyond the southern front of the refectory and are connected at the end by a single-storey wing with a gable roof, about the purpose of which the sources give no information.

The outer walls are windowed according to the uses of the space behind them, mostly with rectangular openings and sometimes with drapery and segmental arches in the style of the Renaissance .

The walls facing the courtyard of the cloister are architecturally designed, especially on the ground floor, to delimit the cloister galleries. Each of the four walls of the galleries is broken through by almost identical arcatures. These are subdivided by strong buttresses that are equipped with different gradations and sloping covers on top. They show that there is a vault on the inside, the belt arches and cross ribs of which generate shear forces, which they absorb and divert into the foundations. They reach approximately to the level of the inner vault apex.

In the lower area, the wall sections open up with four slender arched arcades each. The edges of the arches are broken with wide chamfers . The two inner arches stand together on rectangular pillars, which are flush with the surface of the towering walls and are equipped with profiled, cantilevered transoms and a strong base. The outer arches stand on the outside on multi-profiled warriors embedded in the pillars and on the inside together with the inner arches on twin columns arranged one behind the other, which are equipped with simply sculpted warriors, multi-profiled warriors, simply sculpted bases and powerful plinths.

In the upper wall sections of the ground floor, pointed blind arcade arches made of double round profiles are attached to the wall surfaces, which protrude above their arches behind the buttresses. This indicates that these buttresses were built in front of the wall surfaces afterwards, when the new ribbed vaults were installed, which also generated shear forces. This suggests that the cloister was not vaulted in the Romanesque era, but was perhaps covered with a pent roof construction and a wooden beam ceiling that did not require buttresses. In each of the arched fields a large, predominantly circular ox-eye is left open, in some cases these are also rounded triangles and squares. Remains of tracery can be seen in the last oculi. The oculus in the eastern yoke of the south gallery is walled up halfway up, except for a wide open slot in the middle. A small free-swinging bell hangs in it.

The famous Griffouls fountain of Valmagne is located in the cloister courtyard in the middle in front of the south gallery and exactly opposite the entrance to the monks' refectory, as the rule required. Before entering the dining room and touching the bread, as a symbol of the body of Christ, the monks had to do a ritual hand washing. The Diana source, already discovered by the Romans, in the mountains above the monastery, supplied the various basins of the monastery with clear drinking water before it could flow through drainage channels into the Etang de Thau.

The octagonal edging of the fountain house is made up of reused elements from the Romanesque monastery. For example, the octagonal sections, each made up of three arched arcatures, the arched edges of which are broken up into round profiles. They stand on graceful twin columns, which are connected to one another by a wide variety of decorative shapes, such as three-pass, four-leaf shapes, ring shapes and others. The double columns with their connections are each carved from a single block of stone. The outer arches of the arcatures stand on the outside on sturdy pillars that mark the eight corners of the fountain house, the edges of which are dissolved into columns with capitals and bases.

In the center of the fountain house is the large octagonal fountain basin with a three-tiered fountain column in the middle, which carries a stone bowl about a third of its height and presents eight masks in two-thirds of its height, which spit the water into the basin, that of mosses is densely overgrown. From there, the water flows through another eight masks into the large lower basin. The upper third of the column is an octagonal stele that tapers conically towards the top and is crowned by a stone ball.

Eight strong vaulted ribs protrude from the pillars of the eight corners of the fountain house, but they do not have any vaulted gussets, but remain open. They meet in the center of the fountain house in a "keystone" in the form of an octagonal long rod, which is crowned by a strong knob above the open "vault" and below which it extends a good bit down and ends there in a smaller knob. Shortly before the ribs meet, a slender twig grows out of their underside, arching downwards and supporting itself on the hanging “keystone” directly above the lower knob. This framework is lushly covered with vine leaves and forms a shady roof in summer.

- Gallery fountain

Interior of the convent building

The most important rooms of the convent include the four galleries of the cloister on the ground floor, which is enclosed in the north by the south aisle of the church and on the other sides by other convent buildings. The arched arcatures of the galleries as well as the east wall in the east gallery come from the original Romanesque monastery structure.

The armarium, a round arched niche in the east wall in the NE corner of the cloister, with a parapet half a meter high, is very likely to come from it. The armarium is a book niche that contained the library of the monastery. It seems very small today, but the monks in the 12th century had nothing more than their handwritten prayer books, which they put in the designated space in the niche when they left the church. The design of the arched edge with a curved round bar, which is enclosed by a toothed frieze that is reminiscent of the teeth of a saw, is remarkable. It is an early form of jewelry that was also allowed in the repertoire of the strict Cistercian building rules. Probably later, when the size of the library increased, other rooms were used for its storage, for example in a scriptorium in the wing of the fraterie .

The outer walls of the south and west gallery of the cloister, like the wall of the north gallery, belong to the Gothic construction phase from the beginning of the 13th century. The vaulting of the cloister with cross-ribbed vaults also belongs to this section. The vaulting of the south gallery and parts of the east gallery vault are said to have been built at the beginning of the 14th century.

The inside of the cloister galleries are between 2.20 and 2.60 meters wide. They are each divided into five sections plus a corner section. They are partly square but also slightly rectangular and are all covered by ribbed vaults. The cross ribs have two-step profiled cross-sections. The yoke-dividing belt arches have a similar profile, the inner one is slightly wider and has three grooves. The ribs and belt arches stand on the outside on the fighters of the Romanesque pillars and opposite on mostly vegetable carved cantilever consoles.

The northern gallery was once used entirely for reading and the mandate , the ritual washing of feet, as a sign of humility, following the example of Christ.

The main entrance from the monastery to the church is located in the north-east corner of the wall of the north gallery. It consists of a rectangular door opening that is cut out in the back wall of a pointed wall niche. Five steps lead up to the floor level of the church, namely into the seventh yoke. The curved edges are divided into multiple profiles with small consoles at their ends. Right next to this entrance is the wall niche of the armarium in the east wall.

In the middle of the north gallery, an incomplete ogival niche is set into the church wall at a height of almost two meters, the curved edges of which are profiled several times. They stand on a double profile that closes the niche horizontally at the bottom. This niche probably marks the location of the grave of a famous abbot, whose identity has remained unknown due to the destruction in the revolution.

At the western end of the north gallery there is a large wall niche, the arch of which is slightly sharpened. There are remains of tracery on the reveals. At the western end of the south gallery there is a St. Mary's altar on the west wall.

In the west gallery there is only one doorway that leads into a connecting passage that leads to a western entrance door and opens up the east wing. In the south gallery there are four door openings that open up the rooms of the south wing.

The east gallery, like the adjoining rooms in the east wing of the convent, is one of the original buildings of the monastery. A number of openings that open up these convent rooms have been left in its east wall. The first door at the north end, just next to the niche in the armarium, leads into the sacristy. It is covered by a segmental arch, which is probably more recent. The door is located in a larger, arched wall niche, the reveal edges of which are dissolved in a narrow circular profile that follows a sawtooth frieze in the arched area. A small opening in the form of a lying oval is cut out between the arch of the door and the wall niche. The niche arch is covered by a narrow cantilevered cornice with some distance. This is followed by the arched, rather wide openings to the chapter house, a middle doorway that is flanked by twin window openings of approximately equal width over parapets. The round arches stand on groups of round and octagonal columns, three of which are placed one behind the other at a short distance, on the very outside in a row and the others in two rows each. The pillars are equipped with rather elaborately decorated capitals, profiled bases on angular plinths. The groups of three and six of the pillars are covered by joint profiled striker plates. The sculptures on these sandstone capitals were probably made during the restoration work in the 17th century. This is followed by a round-arched doorway to the parlatorium and then a window and a door into the staircase that opens up the upper floor.

- Gallery cloister

The entire length of the first floor of the east wing of the convent building dates back to the original Romanesque era when Valmagne joined Cîteaux towards the end of the 12th century, although these were subject to various renovations in later times. The tract extends far beyond the cloister and is as wide in its entire length as the south transept arm of the church and directly leans against its gable wall.

The long, narrow room of the sacristy is covered by a classic barrel vault. This room also served as a private chapel for many abbots. In addition to the entrance door, it has a connecting door directly into the church and another door to the neighboring chapter house. It is illuminated through a large window that opens into a high wall niche and has walls that expand inward and is covered by a segmental arch. In the wall to the church there is another rectangular wall niche.

After the church and the cloister, the chapter house is the most important room in a monastery. The monks met here every morning after early mass, the superiors took their places on the surrounding stone bench, the abbot in the middle of the east wall, under the middle of the three windows. The lay brothers could attend the meetings from the east gallery through the openings in the wall of the chapter room. Each morning a chapter from the Rule of Citeaux was read, and the monks had to publicly accuse themselves of their wrongdoing. You read the list of the dead, the names of the deceased from the other monasteries, because all the monasteries were connected to each other, as the rule required. Messenger of the Order traveled from monastery to monastery and carried the news. Jurisdiction was also practiced in the chapter house. The monastery had jurisdiction on civil as well as all other occasions, except in cases involving the death penalty.

Architecturally, this chapter house is a gem. A single ribbed vault spans the large room on a rectangular floor plan, without any supporting pillars. The ribs end in the corners of the room on consoles sculpted as heads. It has a wide connection with the east gallery of the cloister (see there). The slight difference in level of the floor is bridged by a short ramp. In the east wall there are three slender, arched windows, the walls of which are widened inwards.

On each of the parapets there is an elaborately carved "Vase of Cardinal de Bonzi" from the 17th century. Together with the same two vases on the bench between the windows, there are a total of six vases.

- Gallery Chapter House

The immediately adjoining parlatorium (speaking room) is about the same size as the sacristy and is vaulted like it. Next to the door to the cloister there is a glazed door opposite that opened to the gardens. The parlatorium was also a medical treatment room.

The adjoining room is a very spacious staircase that opens up the rooms on the upper floor. In addition to the door and the window to the cloister, there is a small window in the east wall for exposure. The stone staircase comes from the restorations of Cardinal de Bonzi around the middle of the 17th century.

The further wing of the east wing is about as long as the previous one and dates from the same era. According to the sources, the fraterie (work room of the fratres ) was housed in it, that is, it could serve various uses, such as a scriptorium, a larger armarium and others. It is accessed via a small corridor from the cloister, but it may also have a door to the stairwell and various entrances from the outside. Presumably the scriptorium was also the calefactorium (warm room), usually the only heated room in the entire monastery. Various rooms of this wing have been redesigned by Cardinal de Bonzi.

Today's ground floor south wing goes back with its north wall to the beginning of the 13th century. Its premises come from recent renovations, mainly those of the 17th century. The main components are the rooms of the monks' refectory (dining room). The middle area of the south wing is the largest dining room, which is covered by two ribbed vaults. It can be extended by half with the neighboring, equally vaulted room through a large door. The three room sections are each illuminated by a slender, ogival window. On the west wall of the larger section there is a magnificent Renaissance chimney from the Château Cavillargues. The owners of Valmagne sold the castle in the 19th century to finance the costly renovations of Valmagne. The sources do not provide any information about the location of the kitchen. Usually this is right next to the refectory. If you look at the floor plan of the monastery, only the space between the monks' refectory in the south wing and that of the lay brothers in the south west wing comes into question. It has short connections to both refectories, the cloister and outside.