Akıncı

An Akıncı , dt. Akindschi (also Aqindji or Akyndschy , Ottoman آقنجى İA Aḳıncı , German 'Stürmer, Sturmreiter' , in the German-language literature Renner and Brenner ), was a member of irregular - i.e. mostly unpaid and dependent on robbery and slave trade - riding troops of the Ottomans .

Uncertainty in the nomenclature

The terms Akıncı , Deli and Tatars (which always refer to the Crimean Tatars ) are not clearly separated from each other in some sources and publications. It is not completely clear whether and for what period of time these terms are to be regarded as synonymous in literature or are mutually exclusive.

Nicolae Jorga differentiates exactly between Akıncı and Tatars for the 16th century and provides a possible indication of the origin of the confusion of terms: "The Akindschis were joined by thousands of wild Tatars in order to take part in the devastation of the country and the profitable hunt for prisoners." He describes the decline of the Akıncı , who eventually passed their duties on to other troops, and the rise of the Tatars for the time of the sultans Suleyman I and Murat III.

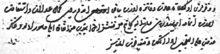

Hammer-Purgstall reports that the Akıncı were dissolved as Ottoman vanguard troops after 1595, referring to the chronicle of the Ottoman historian Na'īmā .

Nevertheless, Jorga names the Akıncı as part of the troops of the Grand Vizier Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed (1635–1676) and in the description of the Ottoman army of 1682, with a footnote making it clear that it is no longer "the old Akindschis".

Palmer calls the group of Tatars named Akıncı by other authors in other publications for the 17th century or specifically for the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683 .

It is not always clear whether Austrian sources from the 17th century, such as local chronicles, refer to the Tartars , the Akıncı or other free-floating troops such as the Bulgarians listed in Jorga by the runners and distillers .

The Akıncı way of life in peacetime

In the memoirs of a Janissary from the 15th century it can be read: “... the other Turks call them çoban, which means shepherds, because they live on sheep and other cattle. They breed horses and wait to be called up for a campaign ... "

Some Akıncı were paid by their beys and given land ownership. They were allowed to keep two to three pairs of oxen on mırı land (state property ) and have the fields tilled by slaves without having to pay öşür (tithe). According to a register from Bosnia from 1516/17, they were exempt from ordinary taxes, compulsory labor and horse recruitment. Information for other times and areas sometimes contradict this. Halil İnalcık explains that as members of the military, the askeri , the Akıncı were exempt from taxes, but not from fees for possible fiefs or commercial profits.

Akıncı also existed in cities . For example, in a defter (register) of the city of Tatar Pazarcık (today Pazardschik , Bulgaria) from 1568 five Akıncı are listed as heads of household.

The number of Akıncı varied greatly. For 1528 they were estimated at 12,000, to which a large number of volunteers came during campaign times, who hoped for permanent entry into the warrior class.

Military duties

The Akıncı represented the most important of the light cavalry units that were available in the context of the provincial troops in addition to the heavy Sipahi cavalry. They came into European consciousness mainly because of their almost annual forays through Austrian and Austrian controlled or claimed areas from 1471 to 1483 as well as during and after the first siege of Vienna by the Ottomans in 1529 as "Renner und Brenner". "Many Christian neighbors [of the Turkish sphere of influence] only knew the wild Akindschis from the large number of Ottoman fighters". The Akıncı were usually stationed in the European border areas and undertook forays even while the regular troops were moving into their camps in order to unsettle the population, to pillage their possessions as supplies and to kill them themselves or to take them prisoner as slaves. They cut off the path of the enemy and, through their incursions, were also supposed to test the mobility and readiness for combat of the opposing army, so they performed tactical scouting activities. Most of them escaped before appropriate countermeasures could be taken.

A typical use of the Akıncı is reported by many authors for the Battle of Mohács (1526) : The Akıncı leader Malkoçoğlu Bali Bey started the battle with his advance party, after a short time staged a pseudo escape and lured the Hungarian cavalry to the sultan's hill, where it was crushed by the phalanx of the Yeniçeri armed with rifles , the Janissaries , with the support of the artillery. In the campaign diaries of Sultan Suleyman, on the other hand, it is described that a detachment of the Hungarians had blown up Bali Bey's battle lines. There is no talk of ruse there. The diary writer mentions Akıncı only once by name.

The strategic unpredictability and shrewdness of the Akıncı as well as the cruelty of the Akıncı , which is known in the West , meant that threatening and their incursion could become an effective diplomatic strategy. Selim II. 1576 to the “King of Vienna” (Beç kıralı) : “We are resolved at any time to counter any attack directed against Poland - with divine assistance - and the Akıncı troops are on standby and by mine Sultan orders to march against you in case Poland and Transylvania should be attacked by you. "

If there was no European war campaign by the regular armies in a year, the Akıncı swarmed under red, black and white flags, breaking up into small flocks, on their own as early as the spring, as they mostly received neither pay nor benefices and their livelihood mostly from depended on the annual robberies. As çete (Freikorps, band of robbers) with less than 100 men or haramili (robbers) with over 100 men, they sometimes even went on the raid several times a year. This happened even in times of peace, for example in 1576 during the peace with Austria. However, the Akıncı risked being deposed as askeri by the sultan and punished. They were not used during regular campaigns in the main army, they undertook extensive raids, so in the summer of 1478 "in the Geiltal or herabwertz gen Kernden" and in 1532 during the siege of the fortress Güns as strong Akıncı dressings under Kasim Beg up to the Enns were advancing . Their reputation as undisciplined troops underscored the repeated damage they did to Ottoman territory. Only in exceptional cases did they take part in campaigns in Asia , such as under Mihaloğlu Ali Bey in 1473 in the fight against the Akkoyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan for his castle Kemah and under Mihaloğlu İskender Bey in 1490 in Egypt.

The Akıncı were used as border guards in the conquered areas of Southeast Europe . They also made up the major part of the armed forces of the Sancakbeys , who headed the lower administrative units called Sancak . Many European sancakbeys came from a few privileged families. In the case of mobilization, they were given the task of compiling and recruiting the Akıncı in missions from the Sultan .

War of faith, raiding and slave trade

The Akıncı understood, according to idealized alto manic chronicles as at least in the 14th and 15th centuries the Bektashi related frontline fighters ( Gazi ) of the religious war against the infidels ; because like the Ottoman rulers they originally came from the Turkish-Turkish cavalry troops, whose religiously motivated fighters were called Gazi (gazi) . They formed an equivalent to the similarly acting Christian-Byzantine Akritai . The self-image of the Gazi is reflected literarily in the poetically exaggerated words of the poet Ahmedi (14th century):

- The religious fighter [Gazi] is the tool of the religion of God.

- No doubt its location will be good.

- The fighter of faith is God's servant, he cleanses this earth from the filth of paganism.

- The fighter of faith is certainly God's sword.

- The religious fighter becomes the protection and refuge of the believers.

- Do not believe the one martyred in God's way to have died. The lucky one lives!

This quote is of course also suitable to describe the devotion of the Christian Akritai , which should not come as a surprise, since Islamic and Christian popular beliefs often mixed in the border area.

The name Akıncı was sometimes used by the first Turkish-Ottoman units of mounted archers that had been put together for the respective military campaign (akın) . With the establishment of a regular army and the wars in Rumelia, the name Akıncı prevailed. It is not clear whether the actual difference between akın ( raiding ) and gazivat (religious war) has been seen or blurred.

If these irregular equestrian troops were units of associated nomadic or semi-nomadic tribal warriors, they were also called Yürük ( Yörük ) .

As a rule, the Akıncı followed a call by a Ucbeys or Sancakbeys approved by the Sultan , who publicly announced the place of the meeting and the aim of the war. So Malkoçoğlu advertised Bali Bey as Sancakbey des Budschak sandschaks in Akkerman with the words: 'I am going out on a great campaign - whoever has guts should come with me, and if Allah wills, I will procure rich booty for everyone! ”Then thirty-to-one gathered forty thousand Gazi (after Uzunçarşılı on the other hand only four thousand Akıncı) in Akkerman and in 1498 they marched with Malkoçoğlu Bali Bey against the Kingdom of Poland in response to the Polish Vltava campaign of 1497.

The promised booty included people, cattle, everyday objects and valuables as well as money. In the 15th and 16th centuries, before the Tatars became the main suppliers, the Akıncı supplied the Ottoman market with slaves from the front lines of the Balkans and Central Europe. Their predatory campaigns not only brought a secure income for the Akıncı and their beys, but also for the sultan, who contributed a fifth of the loot with the pencik . The captured people, in particular, fetched good prices on the slave markets controlled by the Ottoman state. Boys between ten and fifteen years of age promised a particularly high salary, to which the sultan was entitled to a fifth free of charge as part of the boy harvest (devşirme) , but paid well for the remaining four fifths. The Akıncı therefore granted him a kind of right of first refusal.

The Akıncı raids were not always successful. As Gazi and martyrs of the faith, thousands of them often fell in one day fighting with the Christians. A typical example are the approximately 8,000 of an estimated 10,000 Akıncı des Kasım Bey, which were found and destroyed in September 1532 after devastating forays.

The Akıncı-Beys from privileged families

Some loyal families got in early Ottoman period by the sultans of inheritance to the command of the first Gazi mentioned Akıncı Troops awarded the family Mihaloğlu of Sultan Orhan Gazi (1326-1359) even the high command. With their Akıncı, these families conquered large stretches of land in southeastern Europe, the Mihaloğlu family, for example, large areas of the Danube . She also had hereditary locks and a recognized political and military position. Their Akıncı were largely Bulgarians , Serbs and Bosnians .

The families of the Malkoçoğlu , Evrenosoğlu and Turahanoğlu (Turhanlı) were also important . Members of these families were not only Akıncı -Beys and thus often Sancakbeys , but also held other Ottoman offices without, however, rising to the highest ranks (Malkoç Yavuz Ali Pascha, Grand Vizier 1603/04, was an exception). The reason for this was a dream of Sultan Murad I , which he interpreted as a warning against the excessive power of these families. Mutual military support between the Akıncı -Beys was not always guaranteed. In particular, the supreme command given to the Mihaloğlu by Sultan Orhan Gazi was occasionally disregarded by members of the other Akıncı families.

A Sancakbey was the administrative administrator of a Sancak and at the same time the military leader not only of the Akıncı , but also of the armed forces provided by the Tımar owners. Since it mostly had the task of securing the borders, it was also known as uc beyi (border area bey). In the event of a mobilization, the Sancakbeys also commanded the various, mostly temporary, paid groups of volunteers from the reaya (the supporters of the economy such as traders, craftsmen and farmers) as well as Yörük units and with the title çingene-sancakbeyi troops from not registered in the reaya Roma . Christian troops such as the Martolos were also assigned to them .

It is unlikely that the Akıncı families mentioned were of Turkish origin. Jorga thinks at least the Mihaloğlu are of Turkish descent . Köse Mihal , the "loyal friend" of Osman Gazi and ancestor of the Mihaloğlu , reported by the oldest Ottoman source from the time of Bayezid I , Menâkıb-ı Âli-i Osman from Yahşi Fakıh, but was a Christian who converted to Islam, Byzantine governor of Chirmekia ( Harmankaya , today Harmanköy ) and probably Greek. Very few Ottoman dignitaries were Turks. The sultans mostly preferred renegades and their descendants.

The weapons and clothing of the Akıncı

The sources available do not differentiate sufficiently between simple Akıncı riders, Akıncı guides and Akıncı keys. It is also not clear how weapons and clothing can be distinguished from Akıncı and Deli . On Ottoman miniatures Akıncı as well as members of other troops are depicted in combat, sometimes with war clothing and sometimes with representative clothing.

It is documented that Akıncı of all ranks used reflex bows, which today could be called high-tech weapons. Due to their special design, these bows (Ottoman-Turkish yay ) had a very high elasticity for the time and gave the arrows (ok) such a high speed that they could even penetrate armor . In addition to bows and arrows and the associated quivers ( tirkes and kemandan ), the simple Akıncı riders initially only carried a light, rectangular-arched or round, wooden shield (kalkan) , sometimes a lance (mısrak) , later also a saber (gaddare) . In the field they were usually lightly dressed, often wearing a fur hat and sometimes, like the deli , a leopard skin thrown on . The higher ranks of the Akıncı, on the other hand, also wore helmets and chain mail and, in their representative clothing, turbans with plumes. The Akıncı owed their successes in combat not least to their well-trained horses, described as circumcised - "Man and horse already led their own way of life for weeks before the train started in order to be able to cope with all conditions".

The decline of the Akıncı troops after 1595

The Akıncı cavalry troops , which had great military importance since the first half of the 15th century, were decimated in 1595 after the poor leadership of the Grand Vizier Sinan Paşa in the fight against Christian troops and were then unable to recover , no longer promoted by the Sultan and dissolved as permanent units of the Akıncı -Beys. Shortly before that, there were "30-50,000 Akindschis [...] always ready for war on the Danube, as far as Sofia and around Saloniki". Later, the light cavalry of the Ottomans consisted mainly of the Tatars , at times of Bulgarians and deli (osm.-Turkish. Daredevil, crazy, impetuous or from arab. Delîl = leader ), who are said to have been intoxicated with drugs before the fight . Like the Akıncı, these deli were a mixed troop of Turks and members of the Balkan peoples. They functioned as a special guard of Ottoman dignitaries until the end of the 17th century . Nicolae Jorga assigns the military functions of the Akıncı mainly to the Tatars . These were “always at hand; their wild swarms usually formed the vanguard of the army advancing against Poles, Cossacks, Muscovites, or the imperial ones ”. Tatar units were admittedly already before 1595, for example in cooperation with a Malkoçoğlu in 1498 and during Süleyman's last campaign in 1566, as a vanguard group in Turkish service.

A Mihaloğlu Koca Hızır Paşa is mentioned in battles against the Poles under the command of İskender Paşas , but neither the year - it could be 1620 or 1622 - nor the person of this member of the Akıncı family Mihaloğlu are clearly identified. On the occasion of a troop parade during the Hungarian campaign of 1663, one named "Ahmed Beğ, the leader of the Akıncı" and his troops. However, there is no report of a military operation by the Akıncı . Instead, the Tatars play an important strategic role in this campaign. Jorga's descriptions of remnants of the Akıncı , who were no longer "the old Akindschis", suggests that these were of small number and no longer tied to the old Akıncı -Beys. Jorga explains that they were still used at all by stating that “the Ottoman army [around 1680] took on the character of the old swarms of cavalry in the time of the first sultans, since each province in the armed organism retained its individuality and for its own Fame fought. The person of the grand vizier himself finally protected his Bosnian or red-clad arnautical delis [...] with great courage to sacrifice. "

The name Akıncı got lost in the reports for the following years. When describing the military contingent for the war year 1690, for example, Jorga only reads that, in order to form a capable army, “[…] the third Köprili, […] besides Janissaries and Spahis, the Paschas and Beglerbegs with theirs colorful entourage to arms ”shouted. This "motley entourage", in which the Akıncı had set the tone for a long time , was finally no longer needed in its old military function in the following centuries. As early as 1697, the Ottoman army held exercises for the renewed campaign in Hungary under the hapless Sultan Mustafa II “according to the occidental model”.

The decline of the Akıncı was also due to the fact that the Tatars were able to wrest more and more of the slave capture in south-eastern and central Europe and the slave trade from them in the course of the 16th century. İnalcık sees the situation of the Akıncı towards the end of the 16th century in connection with the stagnation of expansion to the west, the simultaneous population pressure from Anatolia, the softening of the strict separation of askeri (warriors and administration) and reaya (carriers of the economy such as traders, craftsmen and farmers), as well as the strengthening of the new Sekban units equipped with firearms and noted a collapse for the Akıncı organization .

Peter F. Sugar gives another reason: the legitimation of the Akıncı and their privileged Beys as Gazi is with the declining expansion into the dar al-Harb (the enemy country) and the subsequent loss of territory of the dar al-Islam (the house or country of the Islam) could no longer be maintained.

Anecdotal and legendary things

Anecdotes and legends shaped by fear and admiration grew up around this Akıncı cavalry, which was regarded as undisciplined , especially after the first siege of Vienna . They determined the image that people made of “the Turks” in Vienna and the surrounding area and beyond in Christian Europe, but in the case of Ottoman folk tales also the image that the Ottomans made of themselves.

- The Akıncı are said to have been feared by their opponents, among other things, because as mounted archers they were able to hit precisely from the back of their galloping horses, whereby all four hooves of the horse had to be in the air at the time of shooting. In this way it is said to have been possible for the Akıncı rider to shoot his arrow from a gallop through the enemy visor slot or to let it snap off exactly at the point in time at which the opponent raised his arm to strike the sword and thus raised the arrow the unarmored area under the armpit could be fatally hit.

- In a Transylvanian song from 1551 it says:

- "The Turks with their dashing Pfeyl,

- They shot out in a quick hurry

- As if it was blowing a whistle. "

- A participant in the military campaigns of Mehmet II (1451–1481) wrote:

- "About the Turkish hunters who are called akıncı"

- “The Turks call their hunters akıncı, which means racer. They are like downpours of rain falling from clouds. And these downpours create great floods and torrential streams that wash over the bank, carrying everything they seize with them, but they do not last long. Like a cloudburst, the hunters or Turkish racers linger only briefly. As soon as they achieve something, they seize and steal it. They murder and wreak such havoc that no rooster crows in those places for many years. The Turkish hunters are volunteers and they take part in the campaigns voluntarily and for their own benefit. "

- The legend of the fall of the Turks :

- On 18./19. September 1532 there was a battle near Leobersdorf - Enzesfeld between the main power of Akıncı, led by Kasım Beg , and the imperial troops under Count Palatine Frederick II , in which the Turks were crushed. An Akıncı shark is said to have been dispersed during the hasty retreat into the Pittental, chased by farmers over the rocks near Gleißenfeld and plunged to their death.

- To commemorate this and as a romantic landscape ornament, Prince Johann II of Liechtenstein had an artificial ruin built on this site in 1824/25, the fall of the Turks .

- In another version, the Akıncı -char is not thrown to death by the peasants, but by the Virgin Mary .

- A series of Ottoman sagas connects the catastrophic defeat of the Akıncı and the death of Kasım Beg near Leobersdorf-Enzesfeld in 1532 with the breaking off of the siege of Vienna by the Turks under Suleyman I in 1529:

- During the siege of Vienna, the Sultan's soldiers had penetrated the city and immediately began to plunder with their own self, without thinking, as Gazi, of the sacred mission of the campaign. They were thrown back and defeated by the Giaurs , and Allah, out of anger at this, caused a premature onset of winter that forced the Ottomans to retreat. The Prophet appeared to the unsuccessful Sultan in a dream face and commanded him to reconcile Allah through a sacrifice of 40,000 rams. Since it was impossible to find such a huge amount, Suleyman I interpreted the dream to mean that he had to sacrifice 40,000 Gazi. Thereupon Kasım Beg came before the Sultan and offered him to make the sacrifice with 40,000 warriors, including his Akıncı . While these Gazi faced the enemy and suffered the death of faith as a martyr, Suleyman I was able to withdraw unmolested with his army.

To iconography

The Akıncı are recorded in many images from the 15th and 16th centuries. Most of the images, which can hardly be regarded as portraying realistic, can be found on Ottoman miniatures, but also on Western panel paintings, drawings and prints. It is always about the representation of the Akıncı in a special or typical context and from a certain political, religious or aesthetic point of view. So it happens, for example, that occidental images put martial aspects in the foreground, Ottoman images glorifying aspects.

The result is that there is no image that can be assessed as binding and realistic and the meanings of the existing images must always be derived from the context. Therefore, the images in Süleymanname must also be viewed very critically. The illustrations for the Battle of Mohács, on which Akıncı leaders can be found, summarize different time situations and are intended to show a representative picture rather than a realistic battle.

The Akıncı as models for the light cavalry of the Christian armies

After the defeat in the Battle of Nicopolis , parts of the Bosnian forces defeated by the Ottomans probably entered Hungarian service. Equipped with lance, shield and saber, they fought as light cavalry and initially performed the same military functions as the Akıncı . They were called hussars . The "hussarones" are mentioned for the first time in writing in 1481 in a letter written in Latin from the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus . Under his reign, however, the hussars had developed into heavily armored riders.

Emperor Maximilian I also showed a special interest in the Turkish war system, especially in the light and fast Akıncı cavalry . Maximilian I copied this in the form of the hussars, Hungarian horsemen, who stood in the first place at the front. Something similar happened in Poland, where the Hussaria was introduced in the 16th century .

Light cavalry as a vanguard based on the Akıncı model included the Uhlans and Bosniaks .

See also

literature

- Zygmunt Abramowicz (Hrsg.): The Turkish wars in historical research. Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-7005-4486-3 .

- Günther Dürigl: Vienna 1529 - The first Turkish siege. Graz 1979

- Gertrud Gerhartl : The defeat of the Turks at Steinfeld 1532. In: Military historical series , booklet 26, ed. from the Army History Museum Vienna, 1974

- Joachim Hein: Archery and archery among the Ottomans after Mustafa Kani's 'Excerpt from the treatises of the archers' , a contribution to knowledge of Turkish handicrafts and associations. In: Der Islam , Volume 14, 1925, pp. 289-360 and Vol. 15 (1926), pp. 1-78 and pp. 233-294.

- Walter Hummelberger: Vienna's first siege by the Turks in 1529. In: Military historical series , Heft 33, ed. from the Army History Museum, Vienna 1976

- Halil İnalcık : Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History. London 1985 ISBN 0-86078-162-3 .

- Nicolae Jorga : The history of the Ottoman Empire illustrated by sources. Unchanged new edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 1997

- Franz Kurz: History of the land defense in Austria under the Enns. Leipzig 1811

- Josef Matuz : The Ottoman Empire - Basics of its History. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, ISBN 3-534-05845-3 .

- Mihaloğlu Mehmet Nüzhet Paşa: Ahval -i al-i Gazi Mihal . 1897

- Rhoads Murphey: Ottoman Warfare 1500-1700. New Brunswick / New Jersey / London 1999

- Ünsal Yücel: Turkish weapons from the 16th to the 18th century. In: Günter Dürigl: The Viennese civil armory . Armaments and weapons from five centuries , exhibition catalog Schloss Schallaburg near Melk, Vienna 1977

Web links

- The Akıncı family Mihaloğlu ( Memento from April 2, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- A place named after the Akıncı in today's Bulgaria, mentioned in the campaign diaries of Sultan Suleyman I.

- Virtual Museum of the “Karlsruhe Turks' Booty”: The armies of the Ottomans

References, sources and comments

- ↑ a b Ernst Werner , Walter Markov : History of the Turks - From the beginnings to the present , pages 23f and 53. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1978

- ↑ The translation from modern Turkish would be looters, wanderers. In the glossary of tuerkenbeute.de ( memento from November 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) the word is used as osm.-turk. Striker, storm rider specified. Aptly would also be that of akın = power to be derived Stromer what the Streifzügler correspond. Striker can be seen as indirectly derived from akın = rush (synonym for military storm ). In German sources they are also referred to as Renner and Brenner as well as Säckmann and were part of the irregular Turkish cavalry in the 15th and 16th centuries. Since Akıncı is ultimately a military term, the glossary solution is preferred here.

- ^ Gereon Sievernich, Hendrik Budde: Europa und der Orient 800-1900 , page 262.Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag, Berlin 1989

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources . Unchanged new edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 1997, Volume 4, p. 416.

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. Unchanged new edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 1997, Volume 3, p. 379 ff.

- ↑ a b "Chronicle of Na'īmā" (روضة الحسين فى خلاصة أخبار الخافقين), quoted in Joseph Hammer-Purgstall: History of the Ottoman Empire . Volume 4. 1829, p. 250.

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 4, p. 138.

- ↑ a b c d Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire based on sources . Unchanged new edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 1997, Volume 4, p. 161.

- ↑ Alan Palmer: Decline and Fall of the Ottoman Empire. Heyne, Munich 1994 (English original: London 1992), 448 p., P. 27 f, 249, 389.

- ↑ a b Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire based on sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 4, p. 167.

- ^ Franz Kurz: History of the Landwehr in Austria under the Enns. Leipzig 1811, p. 223.

- ↑ a b c Memoirs of a Janissary or Turkish Chronicle. Introduced and translated by Renate Lachmann. Slavic historians Vol. VIII. Graz 1975, p. 163 f.

- ^ A b c d David Nicolle : Armies of the Ottoman Turks 1300–1774 . Osprey Publishing, London 1983, ISBN 0-85045-511-1 , p. 13 f.

- ↑ a b c d e Ernst Werner: The birth of a great power - the Ottomans (1300-1481). Berlin 1978, p. 111 ff.

- ^ Halil İnalcık: Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History. London 1985, p. 16.

- ↑ Machiel Kiel : Tatar Pazarcık. In: Klaus Kreiser u. Christoph K. Neumann (Ed.): The Ottoman Empire in its archives and chronicles . Istanbul 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Halil İnalcık: Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History. London 1985, p. 89.

- ↑ a b Esin Atıl: Süleymanname. Washington 1986, p. 135.

- ^ A b Anton C. Schaendlinger : The campaign diaries of Suleyman's first and second Hungarian campaigns I Vienna 1978, p. 83.

- ↑ a b c d e f Josef Matuz, The Ottoman Empire - Basics of its History. Scientific Book Society Darmstadt 1985, ISBN 3-534-05845-3 , 354 pp., 101.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Kissling: From the Ottoman Empire. In: ders .: Dissertationes orientales et balcanicae collectae III., Die Ottmanen und Europa , Munich 1991, p. 227.

- ↑ a b c d e Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire based on sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 1, p. 480 ff

- ↑ a b c d e f Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire based on sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 2, p. 185 ff

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): From the shepherd's tent to the high gate. Graz u. a. 1959, p. 171.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire - Basics of its History. Scientific Book Society Darmstadt 1985, p. 103.

- ↑ Ferenc Majoros and Bernd Rill: The Ottoman Empire 1300–1922. Wiesbaden 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Anton C. Schaendlinger: The campaign diaries of the first and second Hungarian campaigns Suleyman I. Vienna 1978, p. 16.

- ↑ Anton C. Schaendlinger: Suleyman's letters the Magnificent to vassals, military officials, officials and judges. Transcriptions and Translations, Vienna 1986, p. 41.

- ^ "Copy of the letter that is written to the King of Vienna". from January 20, 1576, in: Kemal Beydilli: The Polish royal elections and Interregnen of 1572 and 1576 in the light of Ottoman archives . Munich 1976, p. 83f.

- ↑ command letter from the Sultan to the Beylerbey of Timisoara of 8 March 1576 (date of delivery of the letter to the Cavus), in: Kemal Beydilli: The Polish royal elections and interregnum of 1572 and 1576 in the light of Ottoman archives. Munich 1976, p. 96.

- ↑ Zygmunt Abramowicz (Ed.): The Turkish Wars in Historical Research. Vienna 1983, p. 31.

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 2, p. 171.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): The pious Sultan Bayezid, the story of his rule (1481-1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus. Graz u. a. 1978, p. 202.

- ^ Letter from the Sultan to Hizir Bey of July 26, 1573, in Kemal Beydilli: The Polish elections and interregions of 1572 and 1576 in the light of Ottoman archives. Munich 1976, MD: 22, 160/313

- ↑ Ferenc Majoros and Bernd Rill: The Ottoman Empire 1300–1922. Wiesbaden 2004, p. 14 ff and P. 44 ff.

- ^ Letter from the Sultan to Hizir Bey of July 26, 1573, in Kemal Beydilli: The Polish elections and interregions of 1572 and 1576 in the light of Ottoman archives. Munich 1976, p. 51 f.

- ^ Franz Babinger: Contributions to the early history of the Turkish rule in Rumelia (14-15th centuries). Brno a. a. 1944, p. 60 f u. Note 92 and 93

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): The pious Sultan Bayezid, the story of his rule (1481-1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus. Graz u. a. 1978, p. 83.

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser: The Ottoman State 1300-1922. Munich 2001

- ↑ As in Surname-i Hümayun about the festivities in Istanbul 1582. Austrian National Library, Cod. HO 70, fol. 32r, line 15 f

- ^ A b Peter S. Sugar: Southeastern Europe under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804. Seattle and London 1977, pp. 9ff.

- ^ Friedrich Giese: The old Ottoman anonymous chronicles. Part II. In: Treatises for the customer of the Orient 17, 1925/28, p. 6.

- ↑ David Nicolle: Armies of the Ottoman Turks 1300-1774. London 1983, p. 8.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı. Osmanlı Tarihi Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, 1998. vol. II, pp. 184-85.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): The pious Sultan Bayezid, the story of his rule (1481-1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus. Graz u. a. 1978, p. 106.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): From the shepherd's tent to the high gate. Graz u. a. 1959, p. 179.

- ^ Halil İnalcık: Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History. London 1985, p. 36.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): The pious Sultan Bayezid, the story of his rule (1481-1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus. Graz u. a. 1978, p. 104.

- ^ Bertrand Michael Buchmann: Austria and the Ottoman Empire. Vienna 1999, p. 94f.

- ↑ a b Esin Atıl: Süleymanname. National Gallery of Art, Washington 1986, p. 167.

- ↑ a b c d Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire based on sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 2, p. 204.

- ^ Franz Babinger: Essays and treatises on the history of Southeast Europe and the Levant I. Munich 1962, p. 355 ff.

- ^ Richard F. Kreutel: Life and Deeds of the Turkish Emperors. The anonymous vulgar Greek chronicle Codex Barberianus Graecus 111 (Anonymus zoras). Graz u. a. 1971, p. 94 f.

- ↑ Franz Babinger: Mehmed the Conqueror and his time. Munich 1953, p. 411 f.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): The pious Sultan Bayezid, the story of his rule (1481-1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus. Graz u. a. 1978, p. 217.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: The Ottoman Empire: Conquest, Organization and Economy. London 1978, I p. 108.

- ↑ Géza Dávid et al. Pál Fodor (Ed.): Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs In Central Europe. Leiden 2000. S. XV

- ↑ Aini Ali Mueddinzade: Collection of feudal laws in the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Ahmed I. 018 d. H. In: The Lehnwesen in den MuslimStaaten , Leipzig 1872, Nachdr. Berlin 1982, p. 63.

- ^ Hans Joachim Kissling: Dissertationes orientales et balcanicae collectae, III. The Ottomans and Europe. Munich 1991, p. 49.

- ↑ Géza Dávid et al. Pál Fodor (Ed.): Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs In Central Europe. Leiden 2000. p. 242.

- ↑ Géza Dávid et al. Pál Fodor (Ed.): Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs In Central Europe. Leiden 2000. p. 241.

- ^ Nicolae Jorga after Leunclavius (Lewenklaw): Annales sultanorum othmanidarum. Frankfurt 1596, column 129

- ↑ Leunclavius: Annales sultanorum othmanidarum. Frankfurt 1596, column 129

- ↑ Mehmed Neşrî : Kitâb-I Cihan-Nümâ - Nesrî Tarihi 1st Cilt, Ed .: Prof. Dr. Mehmed A. Köymen and Faik Resit Unat

- ↑ Ferenc Majoros and Bernd Rill: The Ottoman Empire 1300–1922. Wiesbaden 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Hans Joachim Kissling: Dissertationes orientales et balcanicae collectae, III. The Ottomans and Europe. Munich 1991, pp. 217-225.

- ↑ a b Esin Atıl: Süleymanname. Washington 1986, p. 183.

- ↑ a b c d ZDF Expedition, broadcast from May 2006.

- ↑ Jan Lorenzen and Hannes Schuler: "1529 - The Turks before Vienna", editors: Ulrich Brochhagen (MDR) & Esther Schapira (HR), part 2 of the 4-part ARD documentary series "The Great Battles", TV first broadcast on November 6, 2006.

- ^ Georgius de Hungaria: Tractatus de Moribus Condictionibus et Nequicia Turcorum. After the first edition from 1481, Cologne a. a. 1994, p. 189 [R 6b].

- ↑ a b Illustration from Tarih-i Sultan Süleyman (Zafername). Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (Inv.MS. 413, fol 82a)

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 3, p. 217.

- ↑ Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall: History of the Chane of the Crimea. Vienna 1856, Nachdr. Amsterdam 1970, pp. 141–149.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel (ed.): The pious Sultan Bayezid, the story of his rule (1481-1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus. Graz u. a. 1978, p. 101.

- ^ Description of the battle for 1620 at Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall: The history of the Ottoman Empire. Vienna 1838.

- ↑ Erich Prokosch (ed.): War and victory in Hungary. The Hungarian campaigns of the Grand Vizier Körülüzâde Fâzıl Ahmed Pascha in 1663 and 1664 according to the "gems of history" of his keeper Hasan Ağa .

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 4, p. 162.

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 4, p. 247 f.

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 4, p. 261.

- ^ Halil İnalcık: Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History. London 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Halil İnalcık: Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History. London 1985, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Peter S. Sugar: Southeastern Europe under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804. Seattle and London 1977, p. 191 ff.

- ↑ Eberhard Werner Happel: Thesaurus Exoticorum. Or a treasure chamber well-stocked with foreign rarities and stories: Representing the Asian, African and American nations The Persians / Indians / Sinesen / Tartarn / Egyptians / ... According to their kingdoms ... /. Hamburg: Wiering, 1688.

- ↑ Shown in: Gerhard Pferschy / Peter Krenn (ed.): Die Steiermark. Bridge and bulwark. Catalog of the state exhibition at Herberstein Castle near Stubenberg. Graz 1986, p. 149.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel: In the realm of the golden apple. Graz u. a. 1987, pp. 28-52.

- ↑ a b Micha Wolf (master bow maker), in: Jan Lorenzen and Hannes Schuler: "1529 - The Turks before Vienna", editors: Ulrich Brochhagen (MDR) & Esther Schapira (HR), part 2 of the 4-part ARD documentary "The Great Battles" series, TV premiere on November 6, 2006.

- ^ Ulrich Klever: Sultans, Janissaries and Viziers. Bayreuth 1990, p. 226.

- ↑ burgenkunde.at accessed on December 2, 2006, see last paragraph in the source text.

- ↑ The most beautiful sagas from Austria. Ueberreuter Verlag, Vienna 1989, p. 178.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel: In the realm of the golden apple. Graz u. a. 1987, p. 41ff.

- ↑ Nurhan Atasoy: Turkish miniature painting. Istanbul 1974.

- ^ Christoph K. Neumann: Semiotics and the historical source value of Ottoman miniatures. In: Klaus Kreiser u. Christoph K. Neumann (Ed.): The Ottoman Empire in its archives and chronicles . Istanbul 1997, pp. 123-140.

- ↑ a b Kerstin Tmenendal: The Turkish face of Vienna. Vienna u. a. 2000, p. 18.