Alcibiades I

Alkibiades I (also "First Alkibiades" or "Great Alkibiades", Latin Alcibiades maior ) is a philosophical, literary dialogue in ancient Greek from the 4th century BC. In ancient times it was ascribed to Plato , but modern research has considerable doubts about its authenticity. Researchers who consider the dialogue to be fake usually assume that it was created in Plato's environment and was probably written by one of his students. The designation Alkibiades I serves to distinguish it from Alkibiades II , the "second" or "little" Alkibiades, a dialogue that is also ascribed to Plato and is certainly spurious.

The content is a fictional conversation between the philosopher Socrates and the not yet twenty year old Alkibiades , who later became famous as a politician and general and was very controversial. Alkibiades developed a strong political ambition, but it became clear in the course of the discussion that he lacks clear principles and a well thought-out concept. His incompetence can be traced back to a lack of self-awareness. In this context the philosophical question arises as to what is recognized when someone recognizes himself. The answer is that it is a knowledge of the soul about its own nature. The knowledge gained through self-knowledge should enable the care of the soul - the right handling of it. At the same time, it forms the prerequisite for ethical action, especially in politics.

In antiquity, Alkibiades I was considered the basic script of Platonic anthropology and was highly valued by the Platonists .

Place, time and participants

The fictional dialogue takes place in Athens . The time at which the author lets the conversation take place can be deduced from the stated age of Alcibiades; it is probably the year 432 BC Or the time shortly before.

Alcibiades is depicted as his contemporaries and posterity used to perceive him. He is rich and distinguished, very attractive in appearance, ambitious and haughty, and values bravery above all else. In the course of the conversation, Socrates succeeds in shaking the young man's self-confidence and in showing him his ignorance. The background of the encounter is the homoerotic advertisement of Socrates for the beautiful youth. For the proud Alcibiades, the intellectual confrontation with the far superior Socrates means a humiliation, which he does not hold against the philosopher because he admires him.

content

The reason for the conversation

The conversation starts suddenly. Socrates went to Alcibiades to clarify their relationship. In recent years, Alkibiades has had numerous admirers of his beauty who erotically desired him. The first among them was Socrates, who has so far remained silent in the background, as his daimonion , an inner voice, advised him to restrain. Now Socrates wants to come forward with his concern. Alcibiades, with his arrogance, drove away all other lovers by making them feel their inferiority; only Socrates is left. Alkibiades feels bothered by him, but wants to know the reason for the philosopher's persistence.

The requirement of education

Socrates, who knows the boundless political ambition of his interlocutor, offers himself as an advisor. He wants to convince him that such advice is indispensable for achieving the desired political leadership role. Alkibiades intends to speak before the people's assembly, because this is the only way to gain influence in democratic Athens. He would like to have a say in decisions about war or peace and assert his view. Socrates points out to him that he is making a claim to competence, which he must then satisfy. Now, however, in response to urgent questioning, Alcibiades has to admit that he has no special knowledge that could qualify him for this. He only has his school knowledge, which is useless in politics. Socrates makes it clear to him that the decision about war or peace is a question of justice . Alkibiades admits that even as a child he was convinced that he knew what is right and what is wrong, but that he has never really thought about it or received competent instruction. He has always oriented himself only to the common opinions of the ignorant crowd, although these are contradictory. So he understands nothing about justice.

Against these considerations, Alcibiades objects that justice does not really matter, because politics is not about the just, but about the advantageous. But this argument is of no use to him, because here, too, it shows that he lacks specialist knowledge. He claims that what is advantageous is different from what is just, because what is just has often proven to be disadvantageous and wrongdoing to be beneficial. But since he cannot explain what is advantageous, he cannot substantiate his view. It turns out he's talking about something he can't define. Through a series of didactic questions, Socrates makes him see that there is no difference between what is just and what is advantageous. After this change of opinion, Alcibiades is confused as he now realizes the full extent of his ignorance. If he had knowledge, he would not waver so much in his views. As the discussion has shown, the main problem of the ignorant is not their lack of expertise, but their illusion that they have a perspective. Anyone who wants to become a statesman must first realistically assess their competence and obtain the necessary education. The two interlocutors agree that this is hardly ever the case with the Athenian politicians. Socrates expects someone who is really understanding to be able to teach others to understand. But even the famous statesman Pericles , the guardian of Alcibiades, had not succeeded in imparting his skills to others; as a father he had failed, his two sons had failed. No one had become wiser by dealing with Pericles.

The conversation then turns to the question of successful pedagogy. Socrates praised the excellent upbringing which the great kings of the Persians gave their sons, while the Athenians neglected the educational care of their children. He also considers the principles by which the kings of Sparta are based to be exemplary . An ignoramus like Alkibiades has nothing to oppose the rulers of these two states, the traditional opponents of Athens. He still has a lot to learn. Socrates emphasizes that learning never ends for himself either. One should not let up in the pursuit of knowledge and efficiency.

Self-knowledge and responsibility for yourself

In the following discussion of the question of what the requirements for good government are, Alcibiades again becomes confused and has to realize that he understands nothing about it. Socrates helps him to understand that the ability of a person to take care of his own - his property - is different from the ability to take care of himself, that is, to improve himself. Caring for oneself presupposes self-knowledge. First of all, it is important to understand what is meant by "yourself". The "self in itself" or "self itself" (autó to autó , autó tautó) cannot be the body, nor a whole made up of body and soul, but only the soul, the guiding authority that uses the body. According to Socrates' conviction, it alone makes a person; it is his self. The body is only a tool and, as such, belongs to the possession, the “his” of the human being. This also has consequences for love: whoever loves the body of Alcibiades does not love himself, but only an object that belongs to Alcibiades. The love of the body ends when it loses its attractiveness. It is different with love for the soul. That is why Socrates, in contrast to the other lovers, sticks to Alcibiades, although he is no longer a youth, i.e. has passed the age on which the interests of homoerotics tend to concentrate. The body has already passed its heyday, but the soul should now blossom.

How the soul can recognize itself is illustrated by Socrates with the famous mirror comparison. Since it is unable to perceive itself directly, it needs a mirror, just as an eye can only see itself through reflection in an external object. To the eye, this mirror can be another person's eye; when it looks into its pupil, into the highest-ranking part of the strange eye, it sees itself at the same time. The soul must also look into another soul in order to recognize itself, namely in its highest, most divine part, in that of wisdom has its seat. By directing her attention to the divine, she can best attain self-knowledge.

Self-knowledge means, as Socrates further explains, prudence (sophrosyne) . Only thanks to her can a person know what is good and what is bad for him. Therefore, someone who strives for a leadership role in the state must first adopt justice and prudence in order to be able to spread these virtues. As long as one is unable to do so, one should not lead, but rather remain in a subordinate position and allow oneself to be ruled by someone better. Alkibiades can be convinced of this. He now wants to join Socrates and strive for justice under his leadership.

Question of authenticity and time of origin

The authenticity of the dialogue has been very controversial since the 19th century. The date of its creation is related to the assessment of the question of authenticity. There is consensus that Alcibiades I , if it does not come from Plato, was written among his students in the academy . Proponents of inauthenticity point to suspicious linguistic peculiarities. They claim that the structure is reminiscent of Plato's early dialogues, which excludes a classification under the later works, but that Alcibiades I does not have certain characteristics typical of the early works. The conversation shows a strikingly didactic character, the line of thought is too methodical, too linear and too flat, it corresponds more to a textbook than a dialogical search for truth; it lacks the profundity typical of Plato. Proponents of the opposing position dispute the validity of this argument, which is based on prejudice and jumping to conclusions. Pamela Clark put forward the hypothesis in 1955 that Plato had only written the last third of Alcibiades I , perhaps after the death of one of his students, who was the author of the first part. As early as 1809, Friedrich Schleiermacher brought the idea of an only partially authentic work into play; he had considered the possibility that it might be a design by Plato that a pupil later worked out.

If Plato is the author, many scholars believe that dialogue is one of his early or middle works for reasons of content. Nicholas Denyer regards it as an old work; he advocates its creation in the early fifties of the 4th century.

Text transmission

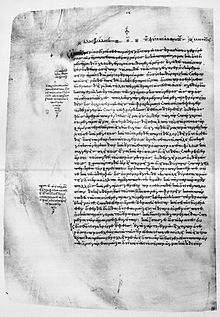

From ancient times there are fragments from two papyrus manuscripts from the 2nd century. The medieval text tradition consists of six manuscripts. The oldest of them was made in the year 895 in the Byzantine Empire for Arethas of Caesarea .

reception

Antiquity

The authenticity of the dialogue was never doubted in ancient times. It was appreciated, studied and commented on. In particular, the anthropology of Alcibiades I , the equation of man with the rational soul, met with a strong, but ambiguous response. This fundamental doctrine of Platonism has been associated with Alcibiades I for posterity since antiquity , because there it is presented with particular clarity and decisiveness and demarcated from the competing anthropological models.

Presumably Aristotle took over the thought of the reflecting eye from Alcibiades I in his now lost dialogue Erotikos . In the 2nd century BC Chr. Has become the historian Polybius in the literary description of a conversation that he met the younger Scipio had led, possibly from the First Alcibiades be stimulated.

In the tetralogy order , which apparently in the 1st century BC Was introduced, Alcibiades I belongs to the fourth tetralogy. The doxographer Diogenes Laertios counted him to the " Maieutic " dialogues and gave "About the nature of man" as an alternative title. In doing so, he referred to a now-lost script by the Middle Platonist Thrasyllos .

The opinion that was widespread among ancient Platonists was that Alcibiades I was the most suitable dialogue for starting a reading of Plato, and that one should therefore begin with it. Self-knowledge, the necessity of which is set out in Alcibiades I , was the starting point of philosophy. It is possible that Antiochus of Ascalon was born in the 1st century BC. Founded a Platonic school, the first to place the reading of Alcibiades I at the beginning of the study of Plato.

In his fourth satire, the Roman poet Persius (34–62) took up the scenario of the rebuke and instruction of Alcibiades by Socrates.

The philosopher and writer Plutarch used the dialogue as a source for the biography of Alcibiades in his "parallel biographies". In the 3rd century, the Middle Platonist Democritus wrote a commentary on Alcibiades I , which is lost today.

The late antique church father Eusebios of Caesarea added a long excerpt from Alcibiades I to his Praeparatio evangelica . His quotation offers a slightly longer version of the text than the version of the dialogue manuscripts. Whether the additional text, which Johannes Stobaios also passed on, comes from the original version or is interpolated , is disputed in research. If it is an insertion, a Middle Platonic commentator of the dialogue can be considered as the author; then it is a piece of commentary brought into dialogue form. Eusebius may follow an early Judeo-Christian tradition of interpretation of the First Alcibiades .

The Neo-Platonist Iamblichus († around 320/325) counted Alcibiades I in a group of ten particularly important dialogues of Plato. He placed it at the beginning of the lesson in his school and wrote a comment on it, which is lost except for fragments. The Neo-Platonist Proklos († 485) wrote another comment . Based on Iamblichos' assessment of the dialogue, he described Alcibiades I as the beginning of all philosophy as well as self-knowledge. In Alcibiades I , like a seed, the whole philosophy of Plato is contained, which is unfolded in the other dialogues. Only the first part of Proklos' work has survived in full; only fragments of the rest are available. Also Damascius († after 538), the last head of the Neoplatonic school of philosophy in Athens, commented Alkibiades I , wherein he grappled with the view of the critical Proklos. Only a few quotations have survived from this work. The last ancient commentary on Alcibiades I , of which posterity knows, comes from the Neo-Platonist Olympiodorus the Younger († after 565), a scholar who worked in Alexandria . It has been completely preserved in a student manuscript.

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

In the 10th century, the influential Muslim philosopher al-Farabi wrote an overview of Plato's writings with the title "The philosophy of Plato, its parts and the order of its parts from beginning to end". He began - the custom of ancient Platonist following - with the First Alcibiades . Apparently he stuck to his source for the order.

Dialogue was unknown in the Latin-speaking scholarly world of the Middle Ages. It was only rediscovered in the epoch of Renaissance humanism . As in antiquity, Alcibiades I found appreciation among the educated in the early modern period and was generally considered genuine.

In the 15th century the humanist Marsilio Ficino made the work accessible to a broader class of education by translating it into Latin. He began the introduction (argumentum) to his translation with the words that this dialogue was more beautiful than Alcibiades and more valuable than all gold. In 1484 the first print of Ficino's Latin translations of Plato's works, including Alcibiades I , appeared in Florence . The Greek text was published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio in 1513 as part of the first edition ( editio princeps ) of Plato's works.

Modern

In the modern era, doubts about the authenticity of Alcibiades I began. In research, the judgment on the question of authenticity is linked to the assessment of the philosophical and literary quality. Friedrich Schleiermacher was the first to speak out against authenticity in 1809. He judged the work to be “fairly insignificant and bad”, so it could not have come from Plato, although there are also individual “very beautiful and genuinely Platonic passages” to be found in it. Schleiermacher's judgment was momentous; it initiated a widespread, persistent contempt for the First Alcibiades one. Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff , who was convinced of the inauthenticity, judged the dialogue very negatively: He called it "sheep dung" and wrote in his Plato monograph that the author of the work was talentless and misunderstood Plato's statements about the daimonion of Socrates and flattened. The supporters of the contrary opinion did not fall silent. Paul Friedländer was a notable proponent of authenticity and defender of the literary quality of dialogue . Since the late 20th century, more and more positively judging researchers who plead for authenticity have spoken out.

The philosopher Michel Foucault dealt extensively with Alcibiades I in his lectures at the Collège de France , because he saw it as a document of a change in the history of ideas and at the same time saw it as an introduction to classical philosophy. He was also convinced of Plato's authorship. Foucault believed that Alcibiades I demonstrated a fundamental innovation in thinking: it was the first theory of the self. This is based on the discovery of the “subject soul” (âme-sujet) , the introduction of the concept of a “subjective”, reflective self. The question of one's own self does not relate to human nature, but to the subject. The history of subjectivity began with it.

Editions and translations

Editions (partly with translation)

- Antonio Carlini (Ed.): Platone: Alcibiade, Alcibiade secondo, Ipparco, Rivali . Boringhieri, Torino 1964, pp. 68–253 (critical edition with Italian translation)

- Nicholas Denyer (Ed.): Plato: Alcibiades . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-632811 (text edition without translation, with commentary)

- Gunther Eigler (ed.): Platon: Works in eight volumes , 4th edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-19095-5 , pp. 527-637 (reprint of the critical edition by Maurice Croiset, 9th edition , Paris 1966, with the German translation by Friedrich Schleiermacher, 2nd, improved edition, Berlin 1826)

Translations

- Otto Apelt : Plato: Alkibiades I / II . In: Otto Apelt (Ed.): Platon: Complete Dialogues , Vol. 3, Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (with introduction and explanations; reprint of the 3rd edition, Leipzig 1937)

- Klaus Döring : Plato: First Alcibiades. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch et al., Vol. IV 1). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-525-30438-9

- Franz Susemihl : Alkibiades the first . In: Erich Loewenthal (Ed.): Platon: Complete Works in Three Volumes , Vol. 1, unchanged reprint of the 8th, revised edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17918-8 , pp. 815–871

Ancient commentaries

- John M. Dillon (Ed.): Iamblichi Chalcidensis in Platonis dialogos commentariorum fragmenta . Brill, Leiden 1973, ISBN 90-04-03578-8 , pp. 72–83, 229–238 (critical edition of the fragments with English translation and commentary by the editor)

- William O'Neill (Translator): Proclus: Alcibiades I. A translation and commentary . 2nd edition, Nijhoff, The Hague 1971, ISBN 90-247-5131-4

- Alain Philippe Segonds (Ed.): Proclus: Sur le Premier Alcibiade de Platon. 2 volumes, Paris 1985–1986 (critical edition of the Greek text with French translation)

- Leendert Gerrit Westerink (Ed.): Olympiodorus: Commentary on the First Alcibiades of Plato . North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam 1956, reprint (with corrections and additions) Hakkert, Amsterdam 1982, ISBN 90-256-0840-X

literature

Overview representations

- Michael Erler : Platon (= outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , edited by Hellmut Flashar , volume 2/2). Schwabe, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-7965-2237-6 , pp. 290-293, 663-665

- Franz von Kutschera : Plato's philosophy . Vol. 3, Mentis, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-89785-266-7 , pp. 253-262

comment

- Klaus Döring: Plato: First Alcibiades. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch et al., Vol. IV 1). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-525-30438-9

Investigations

- Diego De Brasi: Un esempio di educazione politica: una proposta di analisi dell'Alcibiade primo . In: Würzburg Yearbooks for Classical Studies , New Series, Vol. 32, 2008, pp. 57–110

- Jill Gordon: Eros and Philosophical Seduction in Alcibiades I . In: Ancient Philosophy 23, 2003, pp. 11-30

- François Renaud: Self-Knowledge in the First Alcibiades and in the commentary of Olympiodorus . In: Maurizio Migliori u. a. (Ed.): Inner Life and Soul. Psychē in Plato . Academia Verlag, Sankt Augustin 2011, ISBN 978-3-89665-561-5 , pp. 207-223

Web links

- Alkibiades I in German translation after Schleiermacher

- Alkibiades I , Greek text based on the edition by John Burnet (1901)

Remarks

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 291; Jean-François Pradeau: Introduction . In: Chantal Marbœf, Jean-François Pradeau (translator): Platon: Alcibiade , Paris 1999, p. 19f .; Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 311.

- ↑ See on the picture of Alcibiades David Gribble: Alcibiades and Athens , Oxford 1999, pp. 217–222.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 103a-104e. See the sexy backdrop of dialogue Jill Gordon. Eros and Philosophical Seduction in Alcibiades I . In: Ancient Philosophy 23, 2003, pp. 11–30, here: 11–13, 27–29.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 104e-113c.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 113d-119c.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 119d-124e.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 129b1, 130d4.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 124e-132a.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 132b-133c. For an understanding of the passage, see Jacques Brunschwig: Sur quelques emplois d'ὄψις . In: Zetesis. Album amicorum , Antwerp 1973, pp. 24–39, here: 24–32. Cf. Francesco Bearzi: Alcibiade I 132d – 133c7: una singolare forma di autocoscienza . In: Studi Classici e Orientali 45, 1995, pp. 143-162; Christopher Gill: Self-Knowledge in Plato's Alcibiades . In: Suzanne Stern-Gillet, Kevin Corrigan (Eds.): Reading Ancient Texts , Vol. 1, Leiden 2007, pp. 97–112.

- ↑ Alkibiades I 133c-135e.

- ↑ Overviews of the research opinions can be found in Chantal Marbœf, Jean-François Pradeau (translator): Platon: Alcibiade , Paris 1999, pp. 219f. and Diego De Brasi: Un esempio di educazione politica: una proposta di analisi dell'Alcibiade primo . In: Würzburg Yearbooks for Classical Studies , New Series, Vol. 32, 2008, pp. 57–110, here: pp. 57f. Note 1.

- ↑ For details see Monique Dixsaut: Le naturel philosophe , Paris 1985, p. 377; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, pp. 290f .; Nicholas Denyer (Ed.): Plato: Alcibiades , Cambridge 2001, pp. 14-26; Maurice Croiset (Ed.): Plato: Œuvres complètes , Vol. 1, 9th edition, Paris 1966, pp. 49–58; Eugen Dönt : “Pre-Neo-Platonic” in the great Alcibiades . In: Wiener Studien 77, 1964, pp. 37–51; Jean-François Pradeau: Introduction . In: Chantal Marbœf, Jean-François Pradeau (translator): Platon: Alcibiade , Paris 1999, pp. 24–29; Diego De Brasi: Un esempio di educazione politica: una proposta di analisi dell'Alcibiade primo . In: Würzburger Yearbooks for Classical Studies , New Series, Vol. 32, 2008, pp. 57–110, here: 58–64; David Gribble: Alcibiades and Athens , Oxford 1999, pp. 260-262; Julia Annas : Self-knowledge in Early Plato . In: Dominic J. O'Meara (Ed.): Platonic Investigations , Washington (DC) 1985, pp. 111-138, here: 111-133.

- ↑ Pamela M. Clark: The Greater Alcibiades . In: The Classical Quarterly 5, 1955, pp. 231-240. Cf. Monique Dixsaut: Le naturel philosophe , Paris 1985, p. 377.

- ^ Friedrich Schleiermacher: Plato's works , part 2, vol. 3, Berlin 1809, p. 298.

- ↑ See Diego De Brasi: Un esempio di educazione politica: una proposta di analisi dell'Alcibiade primo . In: Würzburger Yearbooks for Classical Studies , New Series, Vol. 32, 2008, pp. 57–110, here: pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Nicholas Denyer (Ed.): Plato: Alcibiades , Cambridge 2001, pp. 11-14. See Pamela M. Clark: The Greater Alcibiades . In: The Classical Quarterly 5, 1955, pp. 231-240; Jean-François Pradeau: Introduction . In: Chantal Marbœf, Jean-François Pradeau (translator): Platon: Alcibiade , Paris 1999, p. 81.

- ↑ Oxford, Bodleian Library , Clarke 39 (= "Codex B" of the Plato textual tradition). See on the text transmission Nicholas Denyer (ed.): Plato: Alcibiades , Cambridge 2001, p. 26; Antonio Carlini (ed.): Platone: Alcibiade, Alcibiade secondo, Ipparco, Rivali , Torino 1964, pp. 7-46.

- ↑ On the after-effects of the anthropological concept, see Jean Pépin: Idées grecques sur l'homme et sur Dieu , Paris 1971, pp. 71–203.

- ^ Paul Friedländer: Socrates enters Rome . In: American Journal of Philology 66, 1945, pp. 337-351, here: 348-351.

- ^ Paul Friedländer: Socrates enters Rome . In: American Journal of Philology 66, 1945, pp. 337-351, here: 341-348; Julia Annas is skeptical about this: Self-knowledge in Early Plato . In: Dominic J. O'Meara (Ed.): Platonic Investigations , Washington (DC) 1985, pp. 111–138, here: p. 112 note 6.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3: 57-59.

- ↑ Evidence in Heinrich Dörrie , Matthias Baltes : The Platonism in the Antike , Vol. 2, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1990, pp. 96-109 (see pp. 356-369); Jean Pépin: Idées grecques sur l'homme et sur Dieu , Paris 1971, p. 116 Note 1. See Alain Philippe Segonds (ed.): Proclus: Sur le Premier Alcibiade de Platon , vol. 1, Paris 1985, p XII f.

- ^ Pierre Boyancé : Cicéron et le Premier Alcibiade . In: Revue des Études latines 41, 1963, pp. 210-229; Jean Pépin: Idées grecques sur l'homme et sur Dieu , Paris 1971, p. 116 note 1.

- ↑ See Vasily Rudich: Platonic Paideia in the Neronian Setting: Persius' Fourth Satire . In: Hyperboreus 12, 2006, pp. 221-238, here: 224-230. See Walter Kißel (Ed.): Aules Persius Flaccus: Satiren , Heidelberg 1990, pp. 495-498.

- ↑ Olympiodoros, In Alcibiadem primum 113c, ed. Leendert G. Westerink: Olympiodorus, Commentary on the First Alcibiades of Plato , Amsterdam 1982, p. 70; Greek text of the passage and translation by Heinrich Dörrie, Matthias Baltes: Der Platonismus in der Antike , Volume 3, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1993, p. 41 (and commentary on p. 194).

- ↑ Eusebios of Caesarea, Praeparatio evangelica 11, 27, 5-19.

- ↑ See also Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 291; Chantal Marbœf, Jean-François Pradeau (translator): Plato: Alcibiade , Paris 1999, pp. 221–228; David M. Johnson: God as the True Self: Plato's Alcibiades I . In: Ancient Philosophy 19, 1999, pp. 1–19, here: 11–14; Burkhard Reis: In the mirror of the world soul . In: John J. Cleary (Ed.): Traditions of Platonism , Aldershot 1999, pp. 83-113; Francesco Bearzi: Alcibiade I 132d – 133c7: una singolare forma di autocoscienza . In: Studi Classici e Orientali 45, 1995, pp. 143–162, here: 144f.

- ^ Text and translation of the Proklos passage in Heinrich Dörrie, Matthias Baltes: Der Platonismus in der Antike , Vol. 2, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1990, pp. 102-105 (cf. pp. 362f.).

- ↑ The remaining part extends to Alcibiades I 116b.

- ↑ Alain Philippe Segonds (ed.) Gives a detailed account of the Neo-Platonic reception of Alcibiades I : Proclus: Sur le Premier Alcibiade de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 1985, pp. XIX – LXXVI.

- ↑ Marsilii Ficini Opera , Vol. 2, Paris 2000 (reprint of Basel 1576), p 1,133th

- ^ Friedrich Schleiermacher: Plato's works. Part 2, Vol. 3, Berlin 1809, p. 292 f.

- ^ William M. Calder III , Bernhard Huss (Ed.): The Wilamowitz in me , Los Angeles 1999, p. 118 (No. 63); the reasoning is set out on pp. 120–122.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: Platon. His life and his works. 5th edition, Berlin 1959, p. 84 note 3, p. 296 note 1.

- ↑ Paul Friedländer: Platon , Vol. 2, 3rd, improved edition, Berlin 1964, pp. 214-226, 332-335; William M. Calder III, Bernhard Huss (Ed.): The Wilamowitz in me , Los Angeles 1999, pp. 118-120 (No. 63).

- ↑ Nicholas Denyer (ed.): Plato: Alcibiades. Cambridge 2001, p. 14 f .; Michael Erler: Plato. Basel 2007, p. 291.

- ↑ Michel Foucault: Hermeneutik des Subjects , Frankfurt am Main 2004 (translation of the original edition L'herméneutique du sujet , 2001), pp. 53–63, 66–70, 75–86, 94–109, 113–118, 509, 602 .

- ↑ Michel Foucault: Hermeneutik des Subjects , Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 94.

- ↑ Michel Foucault: Hermeneutik des Subjects , Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 63f., 70, 75–86, 113, 225–229. See the criticism by Christopher Gill: Self-Knowledge in Plato's Alcibiades . In: Suzanne Stern-Gillet, Kevin Corrigan (eds.): Reading Ancient Texts , Vol. 1, Leiden 2007, pp. 97–112, here: 100–111.