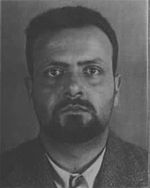

Altiero Spinelli

Altiero Spinelli (born August 31, 1907 in Rome , † May 23, 1986 in Rome) was an Italian politician , member of the European Commission and member of the Communist Party of Italy (PCI) in the European Parliament . He is also considered to be one of the pioneers of the idea of European integration and European federalism .

Communist resistance against Mussolini and imprisonment 1927–1943

As a teenager, Altiero Spinelli joined the Italian Communist Party, which was banned in 1926 after Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922. Spinelli was then active in the resistance against the fascist regime and was therefore arrested in 1927. After ten years in prison, he was exiled to the prison island of Ponza in 1937 and to Ventotene in 1940 , where he stayed until the defeat of the Italian fascist troops in World War II in 1943.

During his imprisonment, Spinelli broke away increasingly from the Communist Party because it supported Stalinism . In 1937 Spinelli was therefore expelled from the party on charges of " Trotskyism ". Thereupon Spinelli approached the ideas of European federalism , according to which an avoidance of war and totalitarianism would only be possible through the establishment of a European federal state.

In contrast to the Paneuropean Union around Count Coudenhove-Kalergi or the British Federal Union around Philip Kerr (Lord Lothian) , which represented confederal concepts of integration based on a confederation of states, Spinelli was an advocate of supranational European integration within the European movement Not only founded by the establishment of federally constituted European institutions, but also constituted from a grassroots-oriented European integration supported directly by the citizens (Constituent Assembly).

His fellow prisoners Ernesto Rossi and Eugenio Colorni were also essential for Spinelli's orientation towards federalism . Colorni was accompanied in custody by his wife Ursula Hirschmann , sister of the revolutionary Marxist and Zionist Albert O. Hirschman ; after Colornis death in 1944 she married Altiero Spinelli.

Ventotene Manifesto 1941

In 1941, Spinelli, together with Rossi and Colorni, wrote the Ventotene Manifesto , in which they described the crisis of the European nation-state and saw the creation of a European federation as the only solution:

“The aim is to create a federal state that stands on solid ground and instead of national armies has a European armed force. We must finally do away with the economic autarchies that form the backbone of the totalitarian regimes. A sufficient number of organs and resources are required to implement the resolutions that serve to maintain general order in the individual states. At the same time, the states should be given that autonomy that allows a plastic structure and the development of a political life according to the special characteristics of the different peoples. "

According to Spinelli's ideas, this European federal state should be founded in the “short, intense period of general crisis” after the end of the Second World War, when a “revolutionary movement” would bring a constitution into force. In the Ventotene Manifesto , Spinelli made no secret of his socialist convictions. For him, the united Europe was at the same time a prerequisite for the liberation of the working class and the overcoming of capitalism :

“The European revolution must be socialist in order to meet our needs; it must work for the emancipation of the working class and the creation of more humane living conditions. "

Due to the clear commitment to a federal constitution , Spinelli is considered to be the founder of “classical federalism”, which strives for European integration through a constitutional act. This is also known as the “constitutional method”, in contrast to the later developed “ Monnet method ” of step-by-step and sectoral integration. Spinelli's basic conviction was that only the creation of joint supranational organs could safeguard the common interest:

“In order to secure the common interest, a suitable apparatus must be in place that is able to enforce the realization of this interest. If this apparatus is missing, if the existing facilities are only suitable for the representation of individual interests, then (...) things must obviously inevitably take a course in which everyone cares for his own interests, regardless of the damage he does to others; this then gives rise to friction and tension that can ultimately no longer be resolved other than through violence. The evils can therefore only be eliminated through the creation of institutions that work out and enforce an international law that prevents the pursuit of goals that only benefit one nation but harm the other. "

Founding of the UEF and political activism in the post-war period

After his release, Spinelli tried to put the demands of the Ventotene Manifesto into practice. On the one hand, he joined the Partito d'Azione , a resistance party against the German occupation of Italy, which Spinelli, however, left again in 1946 after internal conflicts. On the other hand, in 1943 he founded the Movimento Federalista Europeo , an Italian association that propagated a new political constitution for Europe. At the same time he made contact with foreign organizations, such as the Swiss "Europa Union" and French resistance fighters, who also campaigned for European integration. In 1946, after the end of the Second World War, Spinelli was the driving force behind the founding of the Union of European Federalists (UEF), which drove the idea of unification over the next few years.

However, the UEF did not succeed in enforcing a European constitution. In 1948, after the Hague European Congress , the various European organizations (in addition to the UEF, especially the United Europe Movement dominated by Winston Churchill ) came together to form an umbrella organization under the name European Movement . Their activities led to the founding of the Council of Europe in 1949 ; However, this was precisely not a European federal state: It did not affect the sovereignty of the nation states in any way and did not create any influential community organs, as Spinelli had demanded. Spinelli himself therefore expressed his disappointment with the results achieved and accused Churchill of having only built an anti-communist counter-movement to the UEF with the United Europe Movement in order to sabotage its more far-reaching goals.

Spinelli viewed the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952 with skepticism, since it was founded by an international treaty instead of a constituent assembly and was not sufficiently democratically legitimized. Two years later, however, he managed to persuade the Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi to campaign for the establishment of a European Political Community . This should serve as a starting point for a European federal state, the Consultative Assembly of the ECSC (predecessor of the later European Parliament ) work out appropriate proposals. This plan was incorporated into the Treaty on the European Defense Community in 1954 ; but their ratification failed at the end of the same year in the French parliament.

In the years that followed, disappointments and internal conflicts increased in the UEF. In July 1956, it split into the constitutionalist Mouvement Fédéraliste Européen (MFE) around Spinelli, which continued to demand a real European constitution, and the functionalist Action Européenne Fédéraliste (AEF), which campaigned for the gradual expansion of the European Communities. However, both groups exercised little influence on European politics in the following years; Spinelli remained in the public eye as a speaker and leading representative of the greatest possible integration and advised De Gasperi, Paul-Henri Spaak and Jean Monnet on their European policy , among others . In 1965 he founded the Istituto Affari Internazionali , a think tank , of which he was also the first director.

Member of the EC Commission 1970–1976

In 1970 Spinelli was sent to the European Commission by the Italian government , where he took over the industry and research department, and from 1973 industry and trade . In this office he continued to advocate deepening integration, especially in the non-economic area. However , Spinelli viewed the establishment of the European Council of Heads of State and Government in 1974 as critical, as he saw it as a weakening of the supranational organs and a return to intergovernmentalism .

Member of the European Parliament from 1976

In principle, Spinelli remained true to his idea of a constituent assembly and therefore strived for membership in the European Parliament that he considered best suited for this purpose. Since the MPs were still delegated by the national parliaments to the European Parliament in Strasbourg and not directly elected, Spinelli was put up as an independent on the list of the Italian Communist Party in the parliamentary elections in Italy in 1976 . It was not until 1973 that it turned away from the Soviet Union in the so-called “ historical compromise ” and instead turned to Eurocommunism , which affirmed democratic procedures and European integration. Spinelli and other independent candidates on the electoral list gave credibility to this new course, earning the party the best election result in its history in 1976. For Spinelli himself, however, the choice was also associated with a personal tragedy, as his daughter Sara, who had previously been seriously ill, died on the same day.

Immediately after his election to the Italian parliament, Spinelli was seconded to the European Parliament in 1976, where he was deputy chairman of the “ Group of Communists and Allies” (predecessor of today's Confederal Group of the European United Left / Nordic Green Left ). Although many members of the group were clearly more critical of Europe, they left Spinelli extensive freedom of action for his activities, which mostly aimed at cross-faction initiatives to strengthen the role of parliament. In the 1979 European elections , Parliament's first direct election, he was re-elected as an independent on the Communist Party's list.

The draft treaty for a European Union in 1984

With the direct election, the parliament had finally achieved the rank of a “European representative body” for Spinelli, which should legitimately also be authorized to draft a European constitution. In mid-1980 he therefore wrote a letter to all the other members of Parliament in which he made this proposal to them. Shortly afterwards, a small group of MEPs from all political groups met in a Strasbourg restaurant called Au Crocodile to take this initiative forward. The plan that Spinelli submitted to this "crocodile club" provided that the European Parliament would draw up a draft constitution that would then be ratified by the national parliaments - without involving the national governments, which Spinelli did not trust Spinelli to agree to such a surrender of power .

In mid-1981 the members of the Crocodile Club finally brought a motion to the parliamentary plenary session to set up a new committee for institutional questions to draw up this draft constitution. The committee established at the beginning of 1982 was chaired by the Italian socialist Mauro Ferri , and Spinelli himself was rapporteur for the constitutional project.

On February 14, 1984, the European Parliament adopted the "Spinelli Draft", which provided, among other things, legislative powers for Parliament to the extent of today's co-decision procedure . In Article 82, the draft also stipulated the entry into force of the treaty after its adoption by a majority of the member states representing two thirds of the total population of the Community (pan-European plebiscite). The plan of ratification by the national parliaments failed, however: not a single parliament initiated the approval process. In a speech at the European Parliament in May 1984, the French President welcomed François Mitterrand , although the main contents of the draft, but announced only the Einrufung an Intergovernmental Conference , which should discuss further reforms.

This Mitterrand initiative resulted in the establishment of the Dooge Committee in June 1984 , which in turn led to the signing of the Single European Act in 1985 . This was the first major reform of the founding treaties of the European Communities , but in particular the proposals to strengthen the role of Parliament were not included. It was not until the Maastricht Treaty , signed in 1992, that some of the contents of Spinelli's draft constitution were taken up.

Spinelli himself was re-elected in the 1984 European elections, but was disappointed in the following months with further developments, especially since the national governments did not cooperate with the parliament in the preparation of the Single European Act. In terms of content, the reform did not go far enough for him either. He therefore suggested that the European Parliament should work towards ensuring that the 1989 European elections should be formally declared in advance as a constituent assembly election. However, Spinelli died in 1986 before finding enough supporters for the proposal.

Honors

Spinelli received various awards for his services to the construction of Europe, including the 1974 Robert Schuman Prize from the Alfred Toepfer Foundation .

After his death in 1993, one of the European Parliament buildings in Brussels was named after Altiero Spinelli (abbreviated: ASP). The other is named Paul-Henri Spaaks . Since 1998 his name has been on the frieze of the Plaça d'Europa in Barcelona . In addition, the Spinelli Group , an initiative founded in 2010 by MEPs who advocate European federalism, was named after Altiero Spinelli. Since 2017, the European Commission has awarded the Altiero Spinelli Prize for public relations for the dissemination of knowledge about Europe, which is endowed with 25,000 euros.

On August 21, 2016, an EU crisis conference with the participation of the German, French and Italian heads of government took place on Spinelli's former convict island of Ventotene, during which a wreath was laid on his grave.

Fonts

- Manifesto of the European Federalists , Frankfurt a. M .: European publisher, 1958.

- Avventura europea , Bologna: Il Mulino, 1972.

- Il progetto europeo , Bologna: Il Mulino, 1985.

- Una strategia per gli stati uniti d'Europa , Bologna: Il Mulino, 1989.

- Diario europeo (diary), 3 volumes, Bologna: Il Mulino, 1989–1992.

- L 'Europa tra ovest e est , Bologna: Il Mulino, 1990.

- Come ho tentato di diventare saggio (autobiography), Bologna: Il Mulino, 2006.

See also

Web links

- www.altierospinelli.org, homepage about Altiero Spinelli with the Ventotene Manifesto and other links

- Altiero Spinelli's files in the EU Historical Archives in Florence

- Entry on Altiero Spinelli in the database of Members of the European Parliament

- Young European Federalists: Federalism. A historical summary (English version) , with Spinelli's biography

Individual evidence

- ↑ European Commission: Altiero Spinelli - Indomitable Federalist . In: European Union website . (PDF, 648 kB)

- ↑ Piero S. Graglia: Altiero Spinelli , Bologna 2008, pp. 119–123.

- ↑ a b The Ventotene Manifesto

- ↑ Gerhard Klas: Without alternative? , in: Telepolis, June 16, 2005

- ↑ Martin Große Hüttmann / Thomas Fischer: Federalism and European Integration , in: Hans-Jürgen Bieling / Marika Lerch: Theories of European Integration , Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2005, pp. 41–63. ISBN 3-8100-4066-5 pdf

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Brunn: The European Unification . In: Universal Library . No. 17038 . Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-15-017038-0 , pp. 54 ff .

- ↑ Cf. Manuel Müller: Diplomacy or Parliamentarism. Altiero Spinelli's rejection of the Genscher-Colombo Plan 1981 , European history portal 2009.

- ↑ Jan Holling: Lisbon Treaty: Options for action by the member states in the event of non-ratification , NLT Information 2009, p. 19ff. (PDF; 2.7 MB), March 22, 2013.

- ^ The Spinelli Group. Retrieved September 29, 2010 .

- ↑ Commission launches new prize for disseminating knowledge about Europe. Retrieved July 8, 2018 .

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/08/23/five-things-we-learned-from-the-renzi-hollande-merkel-summit/

- ↑ http://www.iiea.com/blogosphere/ventotene-summit-the-spinelli-factor

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Spinelli, Altiero |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian politician, member of the Camera dei deputati, MEP |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 31, 1907 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rome |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 23, 1986 |

| Place of death | Rome |